Thank you for coming,” Rob Yllescas told the members of the Kamdesh shura on October 13. “It makes me happy to come and speak about issues, to resolve them through words and not violence. It is an honor to be with such great men.”

They were sitting outside, near the old Afghan National Police station, now used by the ANA company stationed at the outpost. It was a crisp and sunny day.

“Thank you for bringing peace to this area,” Yllescas said. “There has not been a large attack against Camp Keating in over two months, and I am very proud of the shura for that. Now we need to expand the peace. We need to go to areas such as Kamu and protect the people.”

Anayatullah spoke as well, urging that Kamdeshis obtain voter registration cards so they could have a voice in the presidential and parliamentary elections, scheduled for the following summer. “If we want the right political support, everyone has to participate,” the district administrator explained. “Every male eighteen and over has to register.” The Nuristanis would get to choose five representatives to Parliament.

There were still many unresolved issues on the agenda—one elder from Paprok, for example, complained that the “security” imposed on his village by the Americans blocked food from getting through to residents—but Yllescas felt good about his progress so far and was looking to extend it. He persuaded the ANA and Afghan National Police commanders to start visiting Kamdesh Village at least once a week, with the goal of establishing a permanent Afghan security presence there, thus denying the enemy any safe haven.

Five days later, on October 18, Yllescas, Anayatullah, Jawed, and about fifty others walked up to Kamdesh. Various platoons were conducting overwatch, but the journey there and back was completed without incident, and the visit itself was a smashing success: Jawed and Anayatullah interacted with the Kamdeshis, more villagers pledged to try to resolve their conflicts through government mediation, and a number of residents expressed interest in acquiring voter ID cards for the upcoming election.

The enemy obviously didn’t like any of this. Yllescas, back at Combat Outpost Keating, planned to return to Kamdesh Village the next week, on October 25. But on that day, twenty fighters were spread out in several positions along his path, ready to effect a linear ambush to kill him. In retrospect, it would come to seem that the insurgents might have been focused not just on ambushing Americans in general but on stopping—and killing—Rob Yllescas in particular.

The Americans were ready: Meshkin and a platoon had headed out early to set up an overwatch. They spotted some of the insurgents, fired, and got into a fierce battle. Meshkin called in 120-millimeter mortars, but the rounds were not enough to do the trick, as evidenced by the ongoing fire—from AK-47 assault rifles and a PKM machine gun—that pinned down the lieutenant and two others. Briley and his ANA patrol, on their way to Meshkin’s position, were also pinned down, in their case by a large-caliber rifle, likely a powerful PTRD—a single-shot Soviet antitank gun. The Taliban were bringing in their deadliest weapons, ones they could use to fire extremely lethal shots from afar.

The Blackfoot Troop officers wanted to mortar the insurgents, but they couldn’t figure out exactly where they were, so back at the operations center, Mazzocchi called in Apaches. The only air support available, however, was some “fixed-wing” aircraft—meaning planes, not choppers—and Yllescas, also at the operations center, didn’t want to deal with what could be the long process of getting a bomb drop approved, in order to ensure that no civilians or infrastructure would be harmed. Even if everything happened as quickly as possible, the process would still take as long as fifteen minutes, a lifetime in a firefight.

In the meantime, the Americans had figured out that one of the enemy locations lay to the east, on the other side of a small, rocky spur that jutted off the mountain. Briley grabbed an MK19—a belt-fed machine gun that fired 40-millimeter grenade cartridges—and started shooting grenades up over the spur. Meshkin called in adjustments from his overwatch position.

“Move the barrel one inch down.”… BOOM.

“Now one inch to the left.”… BOOM.

The collaboration seemed to work: the screams of insurgents began to echo in the valley. But the PTRD antitank rifle continued to keep Meshkin and his troops from Red Platoon pinned down. “Grab some guys from Blue Platoon and push out,” Yllescas told Safulko. “Go down the main supply route between Meshkin and the enemy. Draw them out.”

Safulko led about a dozen troops down the road to Urmul. Under fire there, and tipped off by a villager that the enemy was hiding behind a pomegranate tree off in the distance, Safulko looked at the map and called the grid in to Meshkin. Believing that the enemy targeting his own patrol was in the same spot, Meshkin called it in to the fire-support officer, Kyle Tucker, and his 120-millimeter mortars.

Yllescas told Mazzocchi to take two gun trucks to the district center: “Destroy that enemy position,” he ordered. Mazzocchi led two Humvees outfitted with heavy guns into Urmul to do just that, and Briley and his ANA team followed with a four-foot-long, thirty-pound M240B fully automatic machine gun. Once in place, the gun trucks unleashed more than three hundred .50-caliber rounds and almost four hundred MK19 grenade rounds into the enemy positions. Soon the fight concluded, and the enemy retreated.

“Allahu Akbar, you can kill us,” one insurgent taunted on the enemy radio frequency. “We don’t care!”

Many of the surviving fighters, it was later reported, returned to their homes in Kamdesh Village. When Yllescas told him about the incident, Markert concluded: the Hundred-Man Shura had lost control. No one in Blackfoot Troop had even been wounded. The Americans had won the battle—killing five or more insurgents and wounding at least three others—but the enemy had won the strategic fight. The fighters had kept Yllescas and his men out of Kamdesh Village; that had been the point of their attack, and in that, they had succeeded. And they had far worse in store.

Up until July, troops had crossed the Landay-Sin River via a solid wooden bridge that linked Combat Outpost Keating to a piece of land in front of a farmer’s house on the other side. But right after Hutto and 1-91 Cav left, the farmer suddenly tore it down. “He can no longer guarantee our safety on this bridge,” Briley’s interpreter told him after chatting with the man. The farmer had said that “people”—he didn’t specify who—didn’t like his allowing the American soldiers to use it.

A new bridge was then built on the quick, a wooden one made of one-by-four-inch beams laid one after the other, with about an inch of space left between each beam. It was rickety and constructed without nails; pressure and weight kept everything in place. As soldiers crossed it, they could look down and see the river rushing by beneath their feet.

The bridge was a hazard. Troops were forced to cross it one at a time; it was a chokepoint where a soldier could easily be trapped. And even without insurgents trying to pick off those crossing, merely walking on the bridge would cause it to rock and swing violently. A number of troops had seen a little girl drown in the Landay-Sin River after she slipped off the unstable span and was swept away by the rapids. If that could happen to an eighty-pound child, what might befall a two-hundred-pound man lugging another hundred pounds of gear?

The crossing became even more dangerous at the end of October, after someone removed the first six or so boards from the bridge, on the camp side. Meshkin and Red Platoon had to leap across the two-and-a-half-foot gap. This was more than an annoyance.

On October 28, Yllescas and Briley led a joint U.S./ANA patrol north of the outpost. Yllescas was wrapped in his scarf and carrying his own personal knapsack—classic Yllescas, Briley thought, completely confident and reveling in his work. They walked to the bridge. The missing beams had been replaced, surprisingly, with one solid piece of wood, approximately five feet long. No one knew who had done the replacing.

I fucking hate this shit, Briley said to himself. I can’t see what’s underneath the bridge now.

Kyle Tucker had come along on this patrol for a couple of reasons. First, he wanted to check on the micro-hydroelectric plant that was being set up for Kamdesh and several other nearby settlements; not unexpectedly, even though he had sent an interpreter that morning to alert the contractor that they would be coming to inspect the project, neither the contractor nor his workers were there. The second task the fire-support officer hoped to accomplish was to figure out his mortar targets. Because Blackfoot Troop, unlike Bulldog, hadn’t had to deal much with attacks from the north, Tucker carried pages of his predecessor Kenny Johnson’s old grids with him so he could conduct target practice. His mortarman, Sergeant Peter Gaitan, was standing by at Camp Keating. Tucker called in the grids, and Gaitan fired up the mortars, but the exercise didn’t work all that well: the mortars kept missing their marks.

While Tucker was keeping busy with that, Yllescas and Briley saw a lone man acting suspiciously, walking by the riverbank and looking under rocks. “If we were in Iraq, I would shoot this guy just for cause,” Yllescas said. “He’s looking for a place to put an IED.” But this was a different war, with a different set of rules. Plus, there weren’t really many IEDs in this part of Afghanistan.56 At least not yet.

Separately, before daybreak, Safulko and some of the men from Blue Platoon had moved to the Putting Green, northwest of the outpost, from which they could watch the Afghan National Police checkpoints up the road. There was a lot of foot traffic that day, but only about five pickup trucks for the Afghan police to inspect. Small groups of villagers came down from the mountains to gather firewood, bring livestock to the market, or visit with friends and family nearby. The women of Nuristan did much of the manual labor, and a fair number of them carried large bundles of firewood on their backs. Some men were down by the river gathering rocks that they would use to build modest one- or two-story structures.

The Blackfoot troops watched everything intently; something unusual seemed to be afoot. In their chatter over the enemy radio frequency, the insurgents were being particularly cryptic, and the translations subsequently fed to the Americans were poor. At one point, a man walked in front of a woman down the Kamdesh trail, his arms folded. At one of the turning points, he ducked down behind a large rock; after a moment, he resurfaced. He looked suspicious, the soldiers agreed, but he had no weapon. Maybe he had just relieved himself. The couple continued down the trail all the way into Urmul.

A bit later, Safulko spotted two men traveling east on the road, coming toward Keating from the direction of Mandigal. As they approached the checkpoint run by the ANA in front of Camp Keating, they separated and began to walk several hundred feet apart. This struck Safulko as odd—it was as if they were trying to dissociate themselves from each other before they reached the checkpoint. Safulko called the operations center and told Mazzocchi what he’d seen. Mazzocchi radioed the gate and spoke with Staff Sergeant Kris Carroll. ANA troops stopped the two men, who claimed to be on their way to get voter ID cards from the district center down the road. Mazzocchi ran down to the gate to check out the pair himself, but by the time he got there, the ANA soldiers had already released them.

Shortly after noon, the Afghan police up the road called it a day. Around the same time, Yllescas, Briley, Tucker, Staff Sergeant Nicholas Bunch, Sergeant Al Palmieri, and about six ANA troops began walking back to camp. Safulko radioed them and confirmed that he had full observation of them as they prepared to cross the bridge.

Yllescas liked to tease Safulko about his time at Camp Lowell, where the lieutenant and his men had spent much of the summer undersupplied, hanging on by a thread, and getting mortared every day. The mortars had turned life nocturnal for the troops at Kamu: everything they did outside was done at night.

“Hey, Chris,” Yllescas radioed back, “I bet you guys never did shit like this at Lowell.”

They crossed the bridge one at a time: Briley first, followed by his interpreter, then Bunch, who stood guard when he reached the other side. Then Tucker. As Yllescas crossed, Briley called out to him, “Do you want me to call down the over—”

The Marine didn’t get to finish his sentence before a pulverizing explosion knocked him to the ground. When he opened his eyes, he saw Rob Yllescas falling from the sky.

Safulko turned to the bridge and saw a smoke plume billowing upward as the span crumbled into the river. Yllescas—easy to spot even from a distance, with his scarf and his short, stocky frame—was lying faceup on the helicopter landing zone. His legs looked as if they’d been shredded. “Contact!” Tucker yelled into his radio. “Six is down!”57 rang out over the command net.

Initially, they all thought Yllescas had taken an RPG or a mortar round—the explosion was so large, and his wounds seemingly so severe. But Safulko had never known the insurgents to be quite that accurate. It would be a while before everyone realized that Yllescas must have been hit by a radio-controlled IED. He’d been singled out and targeted.

Two groups of insurgents on the southern side of the outpost—on the Switchbacks—now opened up on Safulko’s platoon with small-arms fire, AK-47s, and PKM machine guns. Some of the fire came from the large rock behind which, not long before, Blue Platoon troops had seen that Nuristani man duck.

Briley had a head injury, but he struggled to make his way over to Yllescas. He felt as if he were swimming; everything was blurry and slower than normal. It sounded as if enemy rounds were coming in, but he couldn’t be sure. When he finally got to the captain, Briley gasped. No way was Yllescas alive. His hands were mangled. His legs were mutilated. His head had been smashed into his helmet. Briley tried to pull him away from the scene, but pieces of him began falling off, so he stopped. The Marine wondered why he was the only one there. It mystified him.

Disoriented, Briley couldn’t physically function the way he wanted to; he found himself on his knees, trying to get to a safer place. He noticed another soldier nearby, behind a rock. “Come help me,” Briley pleaded, “come help me.” But the soldier wouldn’t get out from behind the rock. No one would come out. They all thought the explosion had been an RPG, and their experience with RPGs was that they came in bunches. So everyone on the patrol had immediately taken cover. “Get out of there!” Tucker now yelled at Briley. One casualty was bad enough.

Briley, in emotional shock and experiencing a traumatic brain injury, was at once furious and confused. He couldn’t believe what had happened to Yllescas, what they had done. Yllescas had dedicated himself to improving the lives of these people. The Marine turned to the southern mountains, aimed his two middle fingers as if they were weapons, and screamed at the top of his lungs. “FUCK YOU!” he yelled to Kamdesh, to Nuristan, to Afghanistan. “FUCK YOU!”

There was nowhere for Safulko’s platoon to go; while the Putting Green was an excellent observation point, it left troops exposed with few options for escape. All they could really do was hunker down. The Afghan Security Guards who were with the Americans began running up the mountain into a cluster of trees. These local contractors tended to wait and see who they thought was likely to win before they took any action.

“Tell them to take cover and stay put,” a nervous Safulko told the interpreter.

Safulko could see the muzzle flashes from the Switchbacks and farther east. Troops at Camp Keating began returning fire, and the enemy shooting ceased. The troops at the outpost held their fire to observe the enemy response, and insurgents to the east of the Switchbacks shot at Safulko’s platoon. U.S. mortars shut them right up.

At the operations center, Mazzocchi ordered the mortarmen and troops on guard to suppress any enemy fire while a stretcher was taken out to pick up Yllescas. Meshkin radioed to Forward Operating Base Bostick and asked for a medevac, then told Safulko, “I need you guys to hold your position until the medevac clears out.” A call came in to the ops center that a civilian had been spotted near the Switchbacks, a woman out gathering firewood who had unfortunately been caught in the crossfire.

“Continue firing,” Meshkin said.

After hearing the explosion, Captain Steven Brewer, a physician assistant who was the senior medical officer at Camp Keating, grabbed his gear and aid bag and headed for the landing zone, where he found soldiers standing, disorganized, around Yllescas. A small group carefully lifted the captain, put him on the stretcher Mazzocchi had sent out, and carried him into the camp. Brewer ran alongside the stretcher. Yllescas was unresponsive but making gurgling sounds. He would need an airway. His left eye was fixed and dilated. The troops laid him on the table in the aid station. “Doc” Brewer realized that his senior medic, Staff Sergeant George Shreffler, wasn’t there—he was still out with Safulko’s patrol. Brewer thought he heard someone tell him that the medevac was an hour and twenty minutes away. It was one of the many costs of being at a remote outpost.

But it was a cost Meshkin would not tolerate. He sent up an “urgent surgical medevac” request to the 6-4’s squadron XO, Major Thomas Nelson, at Forward Operating Base Bostick. They couldn’t wait for a Black Hawk from Jalalabad, Meshkin told Nelson, who agreed. But pulling a helicopter out of established protocol was no trivial matter. A Chinook and an Apache were just then refueling and about to leave the base to conduct resupply missions in Kunar. In order to commandeer them to try to save Yllescas’s life, Nelson had to get permission from Lieutenant Colonel Markert, who held the birds for a minute while he informed Colonel Spiszer of the plan. “Go to the aid station and grab Doc Cuda,” Markert told Nelson, referring to Captain Amanda Cuda, a physician on base at Naray. “You have three minutes to be on that Chinook.”

In the meantime, Brewer was trying to get an oral airway down Yllescas’s throat to help with his breathing, but Yllescas gagged on it. That was a good sign, that he still had a gag reflex. The PA instead put in a nasal trumpet to make respiration easier. Yllescas’s legs had sustained massive injuries. The major bones of both lower legs had been shattered, and blood was spilling out of the wounds, so Brewer ordered the soldiers helping him to tie tourniquets above each knee and then make splints to try to stabilize the captain’s legs. His arms were relatively uninjured, except for his left thumb, the skin on which had been pulled back like a banana peel. Brewer inserted the lines for two large IVs containing Hextend—an electrolyte solution that assists in restoring blood volume—into the veins on Yllescas’s inner elbows. His airway was obviously still a problem, so Brewer put a mask on the captain’s face and started pumping oxygen into his lungs.

Brewer worked for roughly half an hour on Yllescas—stabilizing him, trying to help his breathing and stop his bleeding—before the Chinook carrying Nelson and Doc Cuda arrived. Yllescas was stable by that point, but not by much. At no time did he ever respond to any of Brewer’s questions or acknowledge any pain. Landing while the firefight was still sputtering, the Chinook set down so hard that it bounced six feet before stopping on the gravelly landing zone. The waiting stretcher crew rushed forward with Yllescas and placed him in the aircraft, where Cuda and Staff Sergeant Dave Joslin, a medic, began working once again to stabilize him as the Chinook took off and flew back toward Forward Operating Base Bostick.

He was in bad shape. Cuda was trained not to think about patients not surviving—there was no time for anything but effort—but it was clear that at a minimum, Yllescas would certainly lose his legs, which were a mess of muscle, flesh, blood, and bone. Best-case scenario.

Back at Keating, at the LZ, Brewer turned to Briley, who had a head injury and was clearly psychologically traumatized. Brewer escorted him to the aid station and injected him with 10 milligrams of diazepam, better known as Valium. The PA gave the order to evacuate Briley on the next bird.58

Villagers came to the entry control point carrying a stretcher on which lay someone completely covered by a blanket. Mazzocchi—now in charge of the outpost—was nervous about letting the stretcher inside the wire. He worried that it might be another IED. It wasn’t. The wounded woman who’d been hit while collecting firewood had been brought to the outpost for medical attention. While Brewer worked to get her stabilized, Mazzocchi spoke to her husband, trying to make the quick transition from soldier to diplomat, as he’d learned from Yllescas. He extended his sincere apologies to the man, who was quite upset—largely, it seemed to Mazzocchi, because his wife was a source of revenue for him. Without her, he would have only three people to work his farm. Until he found another wife, he said, his harvest would be delayed. And it was harvest season.

Mazzocchi asked him how much money the woman’s wounds might cost him.

Four hundred U.S. dollars, he said.

Mazzocchi gave him five hundred from Blackfoot Troop funds. The man seemed content with that. Brewer worked on his wife for about ninety minutes, after which she was medevacked out for higher-level care; when she returned to the area, she was missing one leg below the knee. After that day, whenever Mazzocchi was on patrol and saw him, the woman’s husband was always friendly toward him. It disgusted Mazzocchi. He wondered if he could have saved Yllescas if he’d given a thousand dollars to the Kamdesh shura.

On one level, the man had merely been anxious about his subsistence and his family’s survival—since in Nuristan, women are responsible for all agricultural work—but Mazzocchi would nonetheless come to see him as representing all men. Not just in Kamdesh, not just in Afghanistan. His concern for the well-being of his wife was entirely about her labor and productivity. He wanted the money because money equaled power and influence.

War, Mazzocchi came to think, was always about money and power and never about anything else. Everyone was out for himself. Mazzocchi would quote from Leviathan, the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes’s treatise arguing for a strong government to combat man’s inherent evil, referring to the “general inclination of all mankind, a perpetual and restless desire of power after power, that ceaseth only in death.” Without the constraints of government, human beings would do whatever they wanted, Mazzocchi believed; they were anarchical at their core and concerned only with their own benefit. That was what had motivated Al Qaeda, that was what motivated this Nuristani, and that was what motivated the United States to send thousands of soldiers like himself to this isolated place. He’d joined the Army to find out why 9/11 had happened. He would come to feel that he’d learned why on that October day, when he handed over taxpayers’ money to prevent yet another man from becoming an enemy who would try to kill Americans, while his friend and commander Rob Yllescas lay dying on a medevac.

Specialist Rick Victorino was posted at Camp Lowell that day, so another soldier from the intelligence element, Sergeant “Red” Walker,59 took the lead in trying to figure out who’d been responsible for the remote-controlled IED attack on Captain Yllescas.

Walker went to talk to an Afghan Security Guard commander stationed by the front gate of the outpost, which was now locked down. “This happened within four hundred feet of the front gate of our camp,” Walker said to him. “That’s not good. You need to find out what’s going on.” The commander showed Walker a voter ID card that one of his guards had found by the rocks near the bridge. The photo on the card was of a man in his mid-twenties who had some facial hair. Walker had never seen him before. He asked some of the Afghan Security Guards, but they didn’t recognize him, either.

Around that time, three Nuristani men walked by on the road. Walker stopped them and showed them the ID. “You seen this guy?” Walker asked. “No,” they all said, and they walked away. But then one of them came back. “Can I see that picture again?” he asked. Walker showed him the card. “That guy is in the hotel right now,” the Nuristani said.

The “hotel” was a local inn/restaurant in Urmul, and Walker, along with the Afghan Security Guard commander, headed right for it. As soon as they walked in, they spotted the young man whose picture was on the ID. Walker’s eyes locked onto his for a moment, and then the young Afghan ran out a door. Before he could make it very far, though, the Afghan Security Guards caught him and then brought him back to the front gate at the base.

Staff Sergeant Carroll thought he recognized the man from earlier that day—maybe this was the guy who had been walking with another guy and then suddenly wasn’t anymore, the one the ANA had cleared before Mazzocchi could talk to him? They sat him on a bench, and Walker, through an interpreter, began asking him questions.

“What’s your name?”

“Amin Shir.”

“Where are you from?”

“Paprok.”

“What are you doing here?”

“I came to Kamdesh to get my voter ID card.”

“Who do you know here?”

“Nobody.”

“How long have you been here?”

“Three days.”

Walker knew that the insurgent group in the Paprok area, which attacked Camp Keating every now and then, was headed by the local Taliban leader named Abdul Rahman—the other, “bad” Abdul Rahman.

“Do you know Abdul Rahman?” Walker asked.

“No,” the Afghan said, which Walker knew had to be a lie since everyone in Paprok knew him.

Walker now decided to try out the Expray explosive-detection spray—a three-part, aerosol-based field test kit. He sprayed the contents of the first can onto Shir’s hand, wiped it with a collection paper, and waited to see if the paper turned pink, which would indicate the presence of a specific class of explosives that included TNT. Negative. The intel collector then sprayed the second can on the suspect’s hand and wiped it with a new collection paper. If this one turned orange, it would mean that Shir had recently come in contact with dynamite or another, similar type of explosive.

Walker was in the middle of spraying the third can when the second paper lit up orange.

“Have you handled a weapon or any explosive within the last forty-eight hours?” Walker asked Shir.

“No,” he said. “I’ve never touched a gun, I’ve never touched explosives. I don’t know what you’re talking about. I’m just a farmer.”

The U.S. Rules of Engagement prevented the Americans at Combat Outpost Keating from detaining Amin Shir for longer than seventy-two hours. But the ANA had no such restrictions; its soldiers could hold him for as long as they needed to, and then, if and when they ascertained his guilt, they could give him back to Blackfoot Troop to transfer to the detention facility at Bagram. The ANA troops flex-cuffed Shir, searched and took pictures of him, and placed him in custody.

Walker ordered that Shir first be taken to the aid station, so that Doc Brewer could examine him and attest that he hadn’t been physically abused or mistreated in any way. Brewer wasn’t happy about that; he’d just finished washing Yllescas’s blood off, and he didn’t want to examine the insurgent responsible for mutilating him. But he did it anyway, verifying that Shir had no broken bones or even any bruises.

Walker next took Shir to the outdoor space between the aid station and the operations center, where he questioned him again. Shir’s story had changed: now he said he’d come to Urmul to buy more goats to take back home, because he was a farmer. A little later, he said he’d come to borrow some money to take back home to buy more goats.

Shir also added that he actually did know someone in the area by the name of Hamid,60 a laborer who worked at Camp Keating. Walker asked Sergeant First Class Shawn Worrell, who was in charge of the day laborers, if he knew a Hamid. Worrell said yes, and he went off to find him. Walker then had Shir blindfolded and brought Hamid in to see him. “Do you know this man?” he asked him.

“I’ve never seen him before in my life,” Hamid said.

Walker handed Amin Shir over to the ANA soldiers, who put him in a cell while the intel specialist contacted his chain of command to commence the process of taking an Afghan detainee into an American holding facility. Then he went back to ask Worrell if he could talk to Hamid again. “Of course,” Worrell said. But it turned out that Hamid was no longer at the outpost: he had vanished and was gone forever.

Walker eventually theorized that Shir had come to Urmul and linked up with Hamid three days before he set the explosive. At some point, Hamid described Yllescas to him. The day before the attack, Shir was seen loitering on the concrete bridge near the entrance to Camp Keating (not an uncommon practice for locals), where he confirmed Yllescas’s identity by his headscarf, body size, stature, and gait. That night, with the moon at low illumination, Shir crouched by the northern side of the landing zone and then walked around to the wooden bridge.

Based on the size of the area destroyed, and judging from the firsthand accounts of the soldiers who had witnessed the blast, the IED might have contained ten pounds of explosive material. Walker speculated that Shir might have been able to store an IED that small in his pocket, and that when he took it out by the northern side of the landing zone, his voter ID also fell out. It was dark enough that he didn’t notice it.

This was all theory, circumstantially buttressed by some eyewitness accounts, but Walker became entirely convinced that Amin Shir had targeted for assassination the man who’d become the greatest threat to the insurgents’ influence in Kamdesh.

It was noon in Killeen, Texas, when Dena Yllescas’s cell phone rang. She had just finished nursing their baby girl, Eva.

It was the rear detachment notification captain calling. “Your husband has been injured,” he said.

For some reason, Dena didn’t believe him. She thought he was joking. “Are you serious?” she asked.

“Yes, I’m serious.”

He began giving Dena some phone numbers. She was numb, and her hand was shaking. “Rob was hit by an IED,” he told her. He was in critical condition at Bagram Air Force Base. She was stunned. She hadn’t even known there were IEDs in that part of Afghanistan. The captain began listing her husband’s injuries, a litany that seemed never-ending and that caused Dena to deeply desire that he shut up: she didn’t want to know.

Within hours, Dena’s home was overflowing with friends who had heard the news. Another friend had picked up Rob and Dena’s daughter Julia from school and taken her to play with her own kids. Dena’s sister-in-law Angie had meanwhile volunteered to fly to Texas from Nebraska to get Julia and Eva and bring them back to her home, where she would take care of them while Dena went to be with Rob, wherever that ended up being.

When Julia finally got home, Dena pulled her into her bedroom. “Daddy’s been hurt,” she told her. “But doctors are taking very good care of him. We need to say lots of prayers for him.”

Lieutenant Colonel Markert called Dena a couple of times that day to give her updates and answer any questions she might have. At about 11:30 p.m. in Texas, he called again, and she asked him if she could speak with the doctor who was caring for her husband. “I’ll have him call you as soon as he can,” Markert said.

On the first night that Amin Shir was being held at Camp Keating, Mazzocchi went to talk to an angry Commander Jawed, who felt responsible for what had happened.

“I’m going to avenge Yllescas,” Jawed bitterly declared, “by drowning Shir in the river.”

Mazzocchi told him to calm down. “Shedding more blood won’t accomplish anything,” he said. “We should honor Yllescas by trying to pursue our goals in the valley just as he did.”

Jawed remained upset, however, and he insisted on talking to Shir. Mazzocchi accompanied him to make sure he didn’t do anything stupid. He was also curious to see what Jawed might get out of the man. Most U.S. Army soldiers—Mazzocchi included—were prohibited from directly questioning enemy prisoners of war.

After Jawed had finished yelling at the prisoner, Mazzocchi fed him questions to ask Shir: “Why did you do it? Was it because you wanted to defend the valley? Was it because you wanted to defend your family? Why?”

“I don’t have any money,” Amin Shir said. “They paid me a lot of money for one day’s work. I just wanted to make some money.”

“Who paid you?” Jawed asked him.

Shir paused.

“Bad people from the Mandigal shura,” he said.

So Shir wasn’t an insurgent mastermind—he was just a dumb kid trying to make a little cash in a land of scant opportunity. Hobbes had been proven right yet again.

Shortly after midnight, the surgeon called Dena Yllescas. “How much detail do you want?” he asked.

Everything, she told him. Her imagination had been getting the best of her.

Rob Yllescas had arrived at Bagram approximately four hours after the explosion, he said. He had already had his third surgery. His right leg had been amputated just below the knee, and his left leg had been taken off at the knee. He also had a fracture in his left femur, at the hip. More information came in the next day: Rob was in stable condition and would be flown that day to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany, and from there to Walter Reed Army Medical Center. Markert called and told Dena that some of his colleagues had seen him and said he looked 100 percent better. When Dena explained to Julia that they’d be staying at Walter Reed for a while, the seven-year-old said, “That means daddy has an injury.” Julia seemed to connect Walter Reed with Yllescas’s friend Ryan, who had been injured in Iraq, spent time at Walter Reed, and had an arm and a leg amputated.

“Yes, Daddy has had an injury,” Dena said.

“Did Daddy’s legs get chopped off?” Julia asked.

“Yes, baby,” Dena told her. “Daddy lost his legs, but he is still Daddy, and he loves you very, very much.”

Tears welled up in Julia’s eyes. “Is Daddy still going to be able to wrestle with me?” she asked.

“Yes, baby,” Dena said, “he will be able to do all of the things he used to do with you. But it will take a while before he can do them again.”

Julia thought for a second.

“But Mommy, Eva won’t know Daddy,” she said.

“You mean, she won’t know him without his legs?” Dena asked.

“Yes, Mommy.”

“Baby, Eva won’t know any different, and Daddy will love you both just like he did before,” Dena said. “You know how Ryan has a metal leg? Well, Daddy will have two metal legs.”

Julia scrunched up her face. “Well, I’ll be painting those legs peach,” she declared.

The mood at the outpost was bleak. Feelings of rage, sorrow, loathing, xenophobia, inadequacy, depression—every possible emotion came over the men of Blackfoot Troop. Everyone knew that at best, Yllescas would lose both legs, and that the worst-case scenario was far more probable. Members of Task Force Paladin, newly formed to combat the growing threat of IEDs, flew in from Bagram. The newcomers transferred Amin Shir to Forward Operating Base Bostick and then to the detainee holding center at Bagram.61

The day after the attack on Yllescas, Mazzocchi and Meshkin demanded to meet with the Kamdesh shura; there were a lot of questions that the elders needed to answer, they thought. The elders said they were too scared to come to Camp Keating, but eventually a large group of locals met with the Americans at the Afghan National Police station in Urmul.

Meshkin and Mazzocchi took the lead: What was going on in Kamdesh? Who had organized the attack? Why hadn’t the Americans been warned?

The elders said they were sorry the attack had occurred, but they insisted they had no information to share, and the more they were pressed, the quieter they got. To Mazzocchi, their response was telling—an admission of guilt. They clearly had known that something was going to happen and hadn’t done anything to stop it, but they also wanted to make sure they would keep receiving development funds.

“Captain Yllescas had been calling for you to meet with us for weeks,” Tucker said. “It’s comical to me that you have agreed to come down here only now that something bad has happened. As of now, all projects are on hold. We give you all this money and get nothing in return. We know you have the ability to stop the violence, the madness, the chaos. But you don’t care! And if you don’t care, it makes it hard for us to care.”

One of the elders from the Mandigal shura, an ancient man with a thick white beard, had been staring right into Tucker’s eyes as he spoke. Tucker could feel his simmering glare; the old man was looking at him with an expression that seemed to him to be saying, Look at this stupid fucking kid yelling at us. The twenty-four-year-old lieutenant could only imagine the war and poverty that had marked this man’s life, only guess how little he must care about being barked at by some young pup in yet another occupier’s foreign tongue.

“We’re here for only a short time,” Tucker said. “Then we’re going to return to America, where we have happy lives—where our roads are paved, our children go to school, and our police protect us. You, however, will continue to struggle with violence, as will your children and their children. If you want to make a difference, let us know. We’re here to help.”

The Americans left Urmul and returned to the outpost.

At 7:30 in the morning at Camp Blessing, in Kunar Province, Captain Dan Pecha was summoned to the operations center to answer a call from Major Keith Rautter, the brigade chief of operations back in Jalalabad.

“You’ve got two hours to pack up all your gear,” Rautter told him. “The chopper’s on the way.”

The thirty-three-year-old Pecha, an assistant operations officer with the 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry, had been waiting for his opportunity to command a company, likely somewhere in Kunar Province. His wait was over, but he wouldn’t be in Kunar. Before lunchtime, Pecha was at Forward Operating Base Bostick, meeting with Markert to talk about his new job: he was moving to 6-4 Cav to command Blackfoot Troop at Combat Outpost Keating.

Pecha would come to think of himself as the polar opposite of the charismatic Yllescas—more low-key and unemotional than his predecessor, more calculated and deliberate. The men of Blackfoot seemed timid around him at first; the troops had been together for almost two years by that point, and they had become close. Pecha had never met Yllescas, but he immediately gathered that he’d been a dynamic leader, and instrumental in bonding together the tight-knit Blackfoot Troop lieutenants. It wouldn’t be easy to replace this beloved wounded warrior, but Pecha was confident that his own relationships with Meshkin, Mazzocchi, Safulko, Tucker, and the rest of Blackfoot Troop would develop.

Bonding between the Americans and the locals would be another matter entirely, Pecha knew. Developing such ties required patience and prolonged exchange; when the leader of the effort kept departing, whether through transfer or casualty, the clock was inevitably wound backward. In just two years, the locals in the Kamdesh Valley had gone through seven designated American leaders: Swain, Brooks, and Gooding with 3-71 Cav; Bostick and Hutto with 1-91 Cav; Yllescas and now Pecha himself with 6-4 Cav. And this most recent departure was unprecedented: an attempted assassination of the commander of the outpost. His lieutenants found it incredible that none of the elders knew anything about the plot to kill Yllescas. Someone had housed the culprit, they pointed out; someone had fed him; he must have prayed at a local mosque. Even to Pecha, new on the scene, the apologies that the local powerbrokers were offering sounded insincere.

As surely as the enemy fighters had targeted Yllescas, they now tried to take advantage of his absence. There was an uptick in direct- and indirect-fire attacks, with much larger assaults often coming on Saturdays. (Friday was the Muslim Sabbath, and because the “holy warriors,” as they thought of themselves, believed that their cause was in accordance with their faith, they would frequently launch attacks the following morning.) To counteract any insurgent momentum, the Americans significantly stepped up their patrolling. Mazzocchi had ordered that the bridge be rebuilt—troops needed to be able to get to the Northface somehow—but the process further darkened the mood at the outpost. Most of the soldiers were now convinced that at least some of their “allies” in the construction project were gathering information and passing it on to the enemy. Whatever mistrust the U.S. soldiers already had of the Afghan National Army and the Afghan National Police was magnified. Reports came in of ANA troops selling the bullets out of their own guns to the enemy. Day laborers were observed standing behind U.S. fighting positions within Camp Keating and looking up at the mountains, as if they were doing a “reverse sector sketch”—memorizing what the Americans could see from such locations. American troops began following the day laborers around the outpost. One man was caught with a soldier’s notebook; it was confiscated, and he was sent away.

At Forward Operating Base Bostick, Markert began wondering if any American in Nuristan or Kunar could ever truly have the support of the locals. And whether it was promised to Hutto, Kolenda, or Yllescas, how much did pledged “support” from elders matter anyway if they were unable to prevent their young men from attacking U.S. troops and bases? To Markert, it seemed that Kolenda’s much-touted Hundred-Man Shura was worthless. But at this point, did the shura even have any meaning? Was its backing important? He asked himself, Can it get us enough peace? Even if we have people who are behind us in any of the areas north of Naray, they don’t have the mass to be—and the United States can’t generate the security needed to make them—the voice of authority. Markert knew there were some good people in this part of the world, people who would love for it to be a peaceful place. He also knew they weren’t the ones with the machine guns and the RPGs.

With the insurgency seemingly gaining strength, the members of the Hundred-Man Shura appeared to be losing interest in talking to the Americans. To some ISAF troops, such a disengagement seemed inevitable. Camp Keating had been attacked a few times with the evident complicity of the local villagers, and Camp Lowell at Kamu had been under fire since 6-4 Cav first arrived in the country. Not only Markert but also Mazzocchi believed that Kolenda and Hutto might have been pushing for too much, too soon.62 They suspected that however loudly the 1-91 Cav officers may have tooted their own bugle about their counterinsurgency accomplishments, their fifteen months’ worth of effort wasn’t about to undo decades’, if not centuries’, worth of habits and traditions of self-preservation.

Robert Yllescas’s face was so swollen that when his wife, Dena, walked through the door of his hospital room at Landstuhl on November 1, she barely recognized him. He was wearing a neck brace, was hooked up to a ventilator, and had a tracheostomy tube inserted in his neck. She lifted his sheet: his abdomen was so bruised that it was almost black, and so swollen that he looked nine months pregnant. Since the explosion, he had not regained consciousness.

Dena clutched his hand, intertwining their fingers while she, her mother, and her mother-in-law all talked to him and told him stories—about Julia and Eva, about all the friends and family members who were thinking of him and praying for him. Soon the grandmothers left to buy him some clothes. Dena read her husband the letters Julia had written to him. She kissed his hand and told him how much she loved him. She wished she could have a snapshot of the future; she wanted to know where they would be a year from that moment, because right then, everything seemed so hopeless.

And Dena wept.

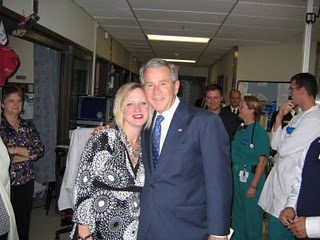

Nine days later, President George W. Bush gave her a big hug.

“I’m so sorry,” the president said. He had tears in his eyes.

They were standing in Rob Yllescas’s hospital room at Bethesda Naval Hospital, wearing hospital gowns and surgical masks. Yllescas remained in bad shape, unconscious, with his jaw wired shut and his legs amputated.

It was November 10, 2008. Yllescas was one of 2,561 U.S. service members who’d been wounded in action in Afghanistan since the war started in October 2001; 621 more had been killed there. In Iraq, 30,764 U.S. troops had been wounded in action, and 4,180 killed.

Less than a week before the president paid this bedside visit, Rob and Dena Yllescas had flown to the United States from Germany on the very day that the nation was electing as its next commander in chief a young, inexperienced freshman senator from Illinois, a liberal Democrat named Barack Obama. Public weariness with President Bush’s two wars was one of the reasons for Obama’s victory over the decorated Vietnam veteran John McCain, a conservative Republican senator from Arizona. Obama seemed less bellicose than McCain. He’d talked about ending the war in Iraq and focusing instead on winning the one in Afghanistan.

President Bush awarded Yllescas the Purple Heart, the medal given to troops wounded in action. Dena tried desperately to wake her husband up. She felt sick, she wanted so badly for him to be awake.

President Bush kept hugging her. “Rob will wake up, and when he does, I will meet him in person again,” he said as he held her.

She and the president left the room and removed their gowns and masks. The president signed a 1st Infantry baseball cap of Yllescas’s and told Dena about Staff Sergeant Christian Bagge, whose convoy had been hit by IEDs in Iraq. Bush had met Bagge at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas. From the hospital bed where he lay with no legs, Bagge had told the president, a famous jogger, “I want to run with you.” In June 2006, Bagge and Bush had done just that together, on the South Lawn of the White House.

“When Rob’s ready and able, maybe you can go wakeboarding with us,” Dena said, referring to the water sport that’s a combination of snowboarding, waterskiing, and surfing.

The president laughed. “I’m too old to wakeboard,” he said.

Eva Yllescas, Memorial Day 2009. (Photo courtesy of Dena Yllescas)