6

The Polonnaruva Kingdom

Indian Summer of Sinhalese Power

The two centuries surveyed in this chapter present every element of high drama. There was, first of all, the expulsion of the invading Cōḷas from the R•jarata after a long war of liberation and the restoration of a Sinhalese dynasty on the throne of Sri Lanka under Vijayab•hu I. This restoration had hardly been consolidated when there was a relapse into civil war and turmoil, but before anarchy had become all but irreversible, a return to order and authority took place under Par•kramab•hu I. There was such a tremendous amount of constructive achievement in administration, economic rehabilitation, religion and culture in the reigns of Par•kramab•hu I (1153–86) and Ni••aṅka Malla (1187–96) that it could easily have taken place over a much longer period of time and still deserve to be called splendid and awe-inspiring. But in retrospect, the activity appears to have been too frenetic, with an over-extension of the island’s economic resources in the restoration of its irrigation network and the architectural splendours of the city of Polonnaruva, and of its political power in overseas adventures.

The Political History Of The Polonnaruva Kingdom1

In his campaign against the Cōḷas, the odds against Vijayab•hu had been a little short of overwhelming till he established a secure base in Rohana. The improvement in his strategic position vis-à-vis the Cōḷas in Sri Lanka coincided with a weakening of Cōḷa power in peninsular India during the reign of Vīrar•jendra I (1063–69). Confronted by a vigorous C•ukya challenge from the Deccan, the Cōḷas were increasingly on the defensive on the mainland and this certainly affected their response to the attacks which Vijayab•hu now launched on their colony in the R•jarata. What had been for long a war of attrition now entered a new phase with an energetic two-pronged attack on the Cōḷa-occupied R•jarata, with Anuradhapura and Polonnaruva as the major targets. Anuradhapura was captured quickly but Polonnaruva, the Cōḷa capital, only fell after a prolonged siege of the now isolated Cōḷa forces there. But faced with total defeat, Vīrar•jendra I was obliged to despatch a relief expedition from the mainland to recapture the R•jarata and if possible to carry the attack back into Rohana. Nevertheless, the respite which the Cōḷas in Sri Lanka gained by this was brief, for the will to struggle on in the face of determined opposition was eroded even further with the death of Vīrar•jendra I. His successor Kulottunga I, a C•lukya prince, came to the throne after a period of acute crisis in the Cōḷa court, and his attitude to the Cōḷa adventure in Sri Lanka was totally different from that of his immediate predecessors R•j•dhir•ja, R•jendra II and Vīrar•jendra—all sons of R•jendra I—for whom it had been a major interest and commitment. Unlike them, his personal prestige was not involved in the fate of the Cōḷa colony in Sri Lanka, and he could—and did—quite dispassionately end the attempt to recoup Cōḷa losses there. What mattered to him above all else was the security of Cōḷa power on the mainland. Thus by 1070, Vijayab•hu had triumphed and the restoration of Sinhalese power was complete.

Vijayab•hu’s role in the prolonged resistance to Cōḷa rule, which culminated eventually in their expulsion from the island, would by itself have ensured his position as one of the greatest figures in the island’s history, but his achievements in the more humdrum fields of administration and economic regeneration were no less substantial. Infusing fresh energy into the machinery of administration, he established firm control over the whole island and presided over both a rehabilitation of the island’s irrigation network and the resuscitation of Buddhism. The established religion had suffered a severe setback during the rule of the Cōḷas who, naturally enough, had given precedence to Saivite Hinduism.

On his death, a disputed succession jeopardized the remarkable recovery from the ravages of Cōḷa rule which he had achieved in his reign of forty years. His immediate successors proved incapable of consolidating the political unity of the island, which had been one of his greatest achievements, and the country broke up once more into a congeries of warring petty kingdoms and principalities. There was an extended period of civil war from which, in time, the remarkable figure of Par•kramab•hu I emerged.

Par•kramab•hu I had the distinct advantage of being closely related to the royal dynasty at Polonnaruva and was therefore in a position to stake a claim to the throne. Once he captured power, his legal status as sovereign was accepted, unlike the claims of his two predecessors at Polonnaruva, Vikramab•hu II and Gajab•hu II. Three clear phases in Par•kramab•hu’s rise to power can be demarcated. The first of these was the establishment of control over Dakkhinadesa and his consecration as Mah•dip•da, a title usually adopted by the heir to the Polonnaruva throne. In the second phase, the tripartite struggle between him as ruler of Dakkhinadesa and the rulers of Polonnaruva and Rohana, Par•kramab•hu’s aim was not so much to capture Polonnaruva as to secure his own recognition as heir to the Polonnaruva throne, and this he achieved. In the harsh conflict that ensued, Par•kramab•hu’s victory was at first by no means certain, but it ended with him very much in control over the R•jarata and Dakkhinadesa, though not of Rohana which still maintained a defiant independence. The third and longest phase began after he took control of Polonnaruva and found his position threatened by the ruler of Rohana. For Par•kramab•hu, intent on establishing his control over the whole island, Rohana was the last and most formidable hurdle to clear. Its ruler was quite as determined as his predecessors in the days of the Anuradhapura kings to protect Rohana’s particularist interests against the central authority in the R•jarata. One of the crucial factors in Par•kramab•hu’s success in this struggle was his capture of the Tooth and Bowl relics of the Buddha which had by now become essential to the legitimacy of royal authority in Sri Lanka.

Once the political unification of the island had been re-established, Par•kramab•hu followed Vijayab•hu I in keeping a tight check on separatist tendencies on the island, especially in Rohana where particularism was a deeply ingrained political tradition. Rohana did not accept its loss of autonomy without a struggle and Par•kramab•hu faced a formidable rebellion there in 1160, which he put down with great severity (there was a rebellion in the R•jarata as well in 1168 and this too was ruthlessly crushed). All vestiges of its former autonomy were now purposefully eliminated, and as a result there was, in the heyday of the Polonnaruva kingdom, much less tolerance of particularism than under the Anuradhapura kings. As we shall see, the country was to pay dearly for this over-centralization of authority in Polonnaruva.

Par•kramab•hu I was the last of the great rulers of ancient Sri Lanka. After him the only Polonnaruva king to rule over the whole island was Ni••nka Malla, the first of the Kalinga rulers, who gave the country a brief decade of order and stability before the speedy and catastrophic break-up of the hydraulic civilizations of the dry zone. The achievements of the Polonnaruva kings Vijayab•hu I, Par•kramab•hu I and Ni••aṅka Malla, memorable and substantial though they were, had their darker side as well. The flaw had to do with a conspicuous lack of restraint, especially in the case of Par•kramab•hu I. In combination with his ambitious and venturesome foreign policy, the expensive diversion of state resources into irrigation projects and public works—civil and religious—sapped the strength of the country and thus contributed to the sudden and complete collapse which followed so soon after his death.

At the death of Par•kramab•hu I, the problem of succession to the throne arose once more and was complicated by the fact that he had no sons of his own. The inevitable confusion and intrigue were cut short by the success with which Ni••aṅka Malla (who introduced himself as a prince of Kalinga, chosen and trained for the succession by Par•kramab•hu himself) established his claims, although it was conceded that Vijayab•hu II had precedence over him by virtue of seniority if not for any other reason. As the scion of a foreign dynasty, Ni••aṅka Malla was less secure on the throne than his two illustrious predecessors. If he was not overwhelmed by the problems inherent in maintaining intact the political structures fashioned by Vijayab•hu I and Par•kramab•hu I, two of the most masterful rulers the island had seen, his successors clearly were. With his death, after a rule of nine years (how he died is not known), there was a renewal of political dissension within the kingdom complicated now by dynastic disputes.

The Kalinga dynasty maintained itself in power with the support of an influential faction within the country. But their hold on the throne was inherently precarious and their survival owed much to the inability of the factions opposing them to come up with an aspirant to the throne with a politically viable claim, or sufficient durability once installed in power. In desperation they raised Lil•vatī, a queen of Par•kramab•hu I, to the throne on three occasions. The ensuing political instability inevitably attracted the attention of Cōḷa and P•ṇ•ya adventurers bent on plunder. These south Indian incursions culminated in a devastating campaign of pillage under M•gha of Kalinga, from which the Sinhalese kingdom of the R•jarata never recovered.

M•gha’s rule and its aftermath are a watershed in the history of the island, marking as they did the beginning of a new political order. From then on, instead of a single ruler for the island there were two, and sometimes three, till the time of Par•kramab•hu VI (1411–66) who established control over the island. He was the last Sinhalese ruler to do so.

Three short extracts from the Cūlavaṁsa capture the essence of the tragedy as near contemporaries saw it:

But since in consequence of the enormously accumulated, various evil deeds of the dwellers in Lank•, the devat•s, who were everywhere entrusted with the protection of Lank•, failed to carry out this protection, there landed a man who held to a false creed, whose heart rejoiced in bad statesmanship, who was a forest fire burning down the bushes in the forest of the good, that is generosity and the like—who was a sun whose actions closed the rows of night lotus flowers—that is the good doctrine—and a moon destroying the grace of the groups of the day lotuses—that is of peace—(a man) by name M•gha, an unjust king sprung from the Kaliṅga line, in whom reflection was fooled by his great delusion, landed as leader of four and twenty thousand warriors from the Kaliṅga country and conquered the Island of Lank•. The great scorching fire—King M•gha—commanded his countless flames of fire—his warriors to harass the great forest—the kingdom of Lank•.2

From the wider picture of the fall of the Sinhalese kingdom the author of the Cūlavaṁsa turns to details in the processes of destruction:

While thus his great warriors oppressed the people, boasting cruelly everywhere, ‘We are Kerala warriors,’ they tore from the people their garments, their ornaments and the like, corrupted the good morals of the family which had been observed for ages, cut off hands and feet and the like (of the people), destroyed many houses and tied up cows, oxen and other (cattle) which they made their own property. After they had put fetters on the wealthy and the rich people and had tortured them and taken away all their possessions, they made poor people of them. They wrecked the image-houses, destroyed many cetiyas, ravaged the viharas and maltreated the lay brethren. They flogged the children, tormented the five (groups of the) comrades of the Order, made the people carry burdens and forced them to do heavy labour. Many books known and famous they tore from their cord and strewed them hither and thither. The beautiful, vast, proud cetiyas like the Ratan•valī (cetiya) and others which embodied as it were, the glory of the former pious kings, they destroyed by overthrowing them and alas! Many of the bodily relics, their souls as it were, disappear. Thus the Damila worriers in imitation of the worriers of M•ra, destroyed in the evil of their nature, the laity and the orderī.3

From there the author of the Cūlavaṁsa turns to what he treats as a particularly serious offence:

The monarch caused the people to adopt false views and brought confusion into the four unmixed castes. Villages and fields, houses and gardens, slaves, cattle, buffaloes and whatever else belonged to the Sihalas he had delivered up to the Keralas. The viharas, the parivenas and many sanctuaries he made over to one or other of his warriors as dwelling. The treasures which belonged to the Buddha and were the property of the holy Order he seized and thus committed a number of sins in order to go to hell. In this fashion committing deeds of violence the Ruler M•gha held sway in Lank• for twenty-one years.4

Polonnaruva ceased to be the capital city after M•gha’s death in 1255 and two new centres of political authority evolved. The heartland of the old Sinhalese kingdom and Rohana itself were abandoned. The Sinhalese kings and people retreated further and further into the hills of the wet zone of the island in the face of repeated invasions from south India. They sought security primarily, but also some kind of new economic base to support the truncated state they controlled.

The second political centre was in the north of the island. Tamil settlers occupied the Jaffna Peninsula and much of the land between Jaffna and Anuradhapura known as the Vanni; they were joined by Tamil members of the invading armies, often mercenaries, who chose to settle in Sri Lanka rather than return to India with the rest of their compatriots. It would appear that by the thirteenth century, the Tamils too withdrew from the Vanni and thereafter their main settlements were confined almost entirely to the Jaffna Peninsula and possibly also to several scattered settlements near the eastern seaboard. By the thirteenth century, an independent Tamil kingdom had been established with the Jaffna Peninsula as its base. The turbulent and confusing history of these two kingdoms is reviewed in greater detail in Chapters 7 and 8.

Foreign Relations: Cōḷas And Pāṇ•Yas

At the beginning of this period the Cōḷas were still the dominant power in south India, with the P•ṇ•yas struggling to maintain themselves as a distinct political entity. As for Sri Lanka, the predominant south Indian state sought to assert its authority over the island, or at least to influence its politics. Sri Lanka’s rulers on their part endeavoured to support the rivals of the dominant power in order to protect their own interests. In brief, they attempted to maintain a balance of power in south India. Thus, for as long as the Cōḷas was the dominant power, Sri Lanka’s alliance with the P•ṇ•yas continued.

The early rulers of Polonnaruva were far too preoccupied with the internal politics of the island to pursue a dynamic foreign policy. But the situation changed when Par•kramab•hu I had consolidated his hold on the island’s affairs. His first venture in foreign affairs, the participation in what is known as the ‘war of P•ṇ•yan succession’ was the inevitable result of Sri Lanka’s alignment with the P•ṇ•yas. This proved to be a long-drawn-out involvement, beginning as it did a little before his seventeenth regnal year and dragging on till the end of his reign. While there was some initial success, the Sri Lanka armies were eventually defeated. Nevertheless, they were able to sustain a determined and prolonged resistance against the Cōḷas, despite the latter’s military superiority. Par•kramab•hu often succeeded in negating a Cōḷa victory, even an overwhelming one, by diplomatic intrigue, for P•ṇ•yan rulers who secured their throne with Cōḷa backing subsequently turned to Par•kramab•hu for assistance, thus rekindling a war which appeared to be fading away, as the Cōḷas reacted by seeking to replace such a ruler with a more reliable and pliant protégé. Thus Par•kramab•hu I achieved what he set out to do, to prevent the establishment of a Cōḷa hegemony over south India. Had the Cōḷas been left unopposed, they could have been a greater threat to the security of Sri Lanka than they were, and may even have endangered Par•kramab•hu’s own position by espousing the cause of Sri Vallabha,5 an aspirant to the Sri Lanka throne who was living in exile in the Cōḷa country. As it was, when Sri Vallabha did organize an invasion, it proved to be a dismal failure.

If this prolonged entanglement in south Indian politics ended in military failure and severely strained the island’s economy, it nevertheless contributed substantially to the impairment of Cōḷa power. Thus while the successors of Par•kramab•hu I inherited a legacy of Cōḷa hostility to Sri Lanka, the Cōḷas were by then on the verge of being eclipsed by their rivals, the P•ṇ•yas.

The last Sri Lankan ruler to intervene in the affairs of south India was Ni••aṅka Malla, who despatched a Sri Lanka expeditionary force to the mainland and, unlike Par•kramab•hu I, accompanied his troops on their mission. His activities there, about which he makes exaggerated claims in his inscriptions, were no more successful militarily than those of Par•kramab•hu’s generals.

By the mid-thirteenth century, the most menacing threat to the enfeebled Sinhalese kingdom came from the P•ṇ•yas, their traditional allies against the Cōḷas. The prolonged crisis in the Sri Lankan polity naturally attracted the Cōḷas, but not any longer with the same frequency or effectiveness as the P•ṇ•yas who, as the predominant power in south India, now sought to establish their influence, if not domination, over Sri Lanka. P•ṇ•yan princes on the Polonnaruva throne, and P•ṇ•yan intervention during the period of M•gha’s rule on the island, bear testimony to the persistence of the traditional pattern of the dominant power in south India seeking to establish its influence on the governance of the island.

The range of Sri Lanka’s political and cultural links with Indian states was not limited to south India. As we have seen, the Sinhalese kingdom had very close ties with Kalinga in the Orissa region, but surprisingly there is little or no Indian evidence bearing on this. On Sri Lanka’s ties with the C•lukyas of the Deccan, some information is available. There was indeed a natural convergence of political interests between Sri Lanka and the kingdoms of the Deccan, prompted by the common desire to keep the Cōḷas in check.

Foreign Relations: South-East Asia

Under the Polonnaruva kings an exciting new dimension of politics emerged—links with south-east Asia, in particular with Burma (then known as R•maṇṇa) and Cambodia.6 Because of her strategic position athwart the sea route between China and the west, there had been, from the very early centuries of the Christian era, trade links between the island and some of the south-east Asian states and China. Now, the principal driving force was religious affinity—a Buddhist outlook, Theravada or Mahayanist—which strengthened ties that had developed from association in trade. Till the eleventh century the cohesion which comes from strong diplomatic and political ties was still lacking. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, at a time of unusual ferment in the politics of the south-east Asian region, with many kingdoms then engaged in a self-conscious search for a new identity, and reaching out for new political ties, formal political relations were established between some of these states and Sri Lanka. The Polonnaruva rulers responded eagerly to these initiatives for they relished the new and attractive vistas in politics, trade and religious and cultural ties which links with south-east Asian kingdoms held out.

In time the religious and cultural ties marked the beginning of Sri Lanka’s powerful cultural influence on south-east Asia. The Polonnaruva period was the heyday of that Sri Lankan cultural influence. For Vijayab•hu I, engaged in a grim struggle against the Cōḷas, there were immediate advantages from this in the form of economic aid from Anauratha of Pagan. The alliance with Pagan appears to have continued after the expulsion of the Cōḷas, and it was to Pagan that Vijayab•hu I turned for assistance in reorganizing the sangha in Sri Lanka, thus underlining the connection between political ties and a common commitment to Buddhism.7

But just as important in the development of political relations between Sri Lanka under the Polonnaruva kings and south-east Asia was the commerce of the Indian Ocean. Kenneth Hall has shown how ‘the upper Malay peninsula became the centre of multi-partite interaction among the Sinhalese of Sri Lanka, the Burmese and the Khmers as the regional trade developed’.8 Conflicting commercial interests led to war between Par•kramab•hu I and Burma.9 Intent on expanding his country’s stake in the maritime trade of the Indian Ocean, Par•kramab•hu I sought to establish close ties with the powerful Khmer kingdom of Cambodia. This aroused the suspicions of the Burmese King Alaungsithu, who viewed it as a potentially serious threat to Burma’s own maritime trade. To protect this latter, he resorted to a policy of obstructing Sri Lanka’s trade in south-east Asia, resulting in strained relations between Burma and Sri Lanka, and eventually war. Par•kramab•hu I despatched an expedition to lower Burma.10 But once this indecisive encounter was over there was a speedy restoration of friendly relations between the two countries.

Between the death of Par•kramab•hu I and the collapse of the Polonnaruva kingdom there are only two instances of Sri Lankan rulers seeking political links or contacts with south-east Asia. These were Vijayab•hu II and Ni••aṅka Malla; the first maintained friendly relations with Burma, and the latter with Cambodia as well. But Ni••aṅka Malla’s claims in this regard are a matter of some controversy.

In a curious way, all these various strands which made up the politics of the island in the last days of the Polonnaruva kingdom were linked together by the only recorded south-east Asian invasion of Sri Lanka. The invasion, which occurred in 1247 when Par•kramab•hu II (1236–70) was the Sinhalese king ruling at Dambadeniya, was led by Chandrabh•nu of T•mbralinga, a petty kingdom in the Malay Peninsula which had established itself as an independent state in the last days of the Sri Vijaya empire in the thirteenth century.11 Par•kramab•hu’s forces defeated Chandrabh•nu, who fled to the Jaffna kingdom, then under M•gha. There he succeeded in securing the throne for himself (how he did so we do not know for certain) and was the ruler in Jaffna at the time of the P•ṇ•yan invasion.

This latter stemmed from P•ṇ•yan rivalry with the Cōḷas, who supported M•gha’s regime in Sri Lanka. Indeed M•gha, as the ruler of the northern kingdom, was no more than a satellite of the Cōḷas. When, by the middle of the thirteenth century, the P•ṇ•yas had established themselves as the dominant power in south India, they were inclined to support the Sinhalese kings against the newly established kingdom in the north of the island.

Their intervention in the affairs of Sri Lanka, if more restrained in its objectives than that of the Cōḷas, was, however, no less governed by considerations of realpolitik. They invaded Jaffna and forced Chandrabh•nu to submit to P•ṇ•ya power, but at the same time there was no inclination on their part to permit the Sinhalese to re-establish their control over Jaffna. Chandrabh•nu was allowed to remain on the throne at Jaffna as a tributary of the P•ṇ•yas. It became evident that one of the limitations imposed on him was that there could be no disturbance of the balance of political power on the island at the expense of the Sinhalese ruler. When Chandrabh•nu embarked on a second invasion of the Sinhalese kingdom, and Par•kramab•hu II appealed to the P•ṇ•yas for help, an expeditionary force was despatched to bring the J•vaka ruler to a realization of the limits of his power. The combination of P•ṇ•yan and Sinhalese forces won an overwhelming victory and Chandrabh•nu himself was killed in the confrontation. Instead of handing over control of the Jaffna kingdom to Par•kramab•hu II, the P•ṇ•yas preferred to install a son of Chandrabh•nu as ruler of Jaffna. When he in turn became a threat to the Sinhalese, the latter once more sought the help of the P•ṇ•yas, who intervened with decisive effect; but Sinhalese control of the Jaffna kingdom was still equally unacceptable to the P•ṇ•yas, and so Āryacakravarti, the leader of the P•ṇ•yan army of invasion on this occasion, was installed as ruler of Jaffna under their overlordship. When the P•ṇ•yan empire in turn collapsed as a result of Muslim inroads into south India, Jaffna became an independent kingdom under the Āryacakravartis.12

Economic And Social Structure

The economic and social structure of the Polonnaruva kingdom, like its art and architecture, was a natural development from, if not a continuation of, those of the Anuradhapura kingdom. It was a hydraulic civilization and a primarily agricultural economy made more prosperous from profits from internal and external trade.

Its astonishing creativity in irrigation was all the more remarkable for the brief period of time over which it was achieved and the massive efforts at restoration which preceded any attempts at expansion. Repair and restoration, by themselves, called for a prodigious expenditure of resources. Most of this work was concentrated in the reigns of three kings, Vijayab•hu I, Par•kramab•hu I and Ni••aṅka Malla, the outstanding contribution being that of Par•kramab•hu I whose reign marked the peak of Sinhalese achievement in hydraulic engineering.13

The Polonnaruva kings were the heirs to several centuries of experience in irrigation technology. But they themselves—and especially Par•kramab•hu I—made a distinctive contribution of their own in honing these techniques to cope with the special requirements of the immense irrigation projects constructed at this time. There was, for instance, the colossal size of the Par•krama Samudra (the sea of Par•krama) which, with an embankment rising to an average height of 12 m and stretching over its entire length of 13.7 km, was by far the largest irrigation tank constructed in ancient Sri Lanka. This stupendous project incorporated two earlier tanks, the Tōp•väva and the Dimbutuluväva. Fed from the south by the Ańgamädilla Canal, it was linked on the north-west with the Giritale Tank and through it with the Älahära System. The earthworks involved in this project were unprecedented in scale and the stonemasonry of this and other irrigation works of this period involved the handling of stone blocks of up to 10.7 metric tonnes in weight.14

Parākrama Samudra, Polonnaruva

Refinement of irrigation technology was demonstrated also in the three weirs built across the Daduru Oya, the only river in the western part of the dry zone to provide anything like a perennial supply of water. The second of these diverted water to the Mahagalla Reservoir (which had been built by Mah•sena) and was a masterly engineering feat whose special feature was the amazing precision with which the large stone blocks of its outer walls were fitted, their joints only 0.64 cm in width.15

The Cūlavaṁsa’s account of the reign of Par•kramab•hu I contains an extensive catalogue of irrigation works repaired, restored, expanded or constructed in his reign. The impression of tireless devotion to this crucial aspect of governmental enterprise in Sri Lanka’s hydraulic society could hardly be described as inaccurate. But it is essential to remember that it was no truer than in the Anuradhapura era that every link and every unit in this intricate irrigation network was working pari passu for any great length of time. They could not have done so, and, in fact, did not. If this perspective appears somewhat to limit the achievement of that era, one must remember that this was the last major phase in the development of irrigation in ancient Sri Lanka. Nothing on this scale was attempted, much less achieved, till the second quarter of the twentieth century, when the Gal Oya Scheme in the present Eastern Province, the first irrigation scheme to be constructed in the very early years of independence from British rule, easily overshadowed the Par•krama Samudra. And so the chronicler’s account can be seen for what it was, evocative and even poignant, for he was lamenting, in a later and more cramped era, the passing of an age of creativity, when the island’s irrigation tanks were no more than stupendous ruins, but yet

. . . the proudest monuments... of the former greatness of their country when the opulence they engendered enabled the kings to lavish untold wealth upon edifices of religion, to subsidise mercenary armies and to fit out expeditions for foreign conquest.16

We turn next, and briefly, to the caste structure of Sri Lankan society under the Polonnaruva kings. Two points are of special interest. There is, first, much stronger evidence of a hierarchical arrangement of castes, though it is difficult to determine the exact or even approximate place of each caste in that structure. The segmentation of Sinhalese society into some of the numerous castes which exist today began before this period, but the process appears to have been accelerated in it. Second, there was increasing rigidity in the observance of caste duties, obligations and rights on the basis of custom and usage. For instance, a Tamil inscription of 1122 reveals that washermen were required to perform their customary duties to members of certain other—presumably ‘higher’—castes and that there would be no remission of this obligation. A rock inscription of Vijayab•hu I at Ambagamuva shows that he had constructed a special platform on Adam’s Peak below the main terrace of the ‘sacred’ footprint for the use of persons of ‘low’ caste. More significantly, there are Ni••aṅka Malla’s repeated references to, and ridicule of, the aspirations of the Govikula (the Goyigama caste, then as now very probably the largest caste group among the Sinhalese, though possibly not at that time the most prestigious) to kingship in Sri Lanka. Quite clearly, this was regarded as a monopoly of the Kshatriyas. This hardening of caste attitudes is attributed to the burgeoning influence of Hinduism on religion and society in Sri Lanka.17

Land tenure in the Polonnaruva kingdom was as much a multi-centred system as it was earlier and its pattern was just as complex.18 There was a wide variety both in the number of individuals and institutions sharing land and rights accruing from land as well in their tenurial obligations. The king had definite claims over most of the land in the kingdom, but these were no obstacles to private individuals in buying and alienating land. To a much greater extent than in the Anuradhapura kingdom, the ‘immunities’—various concessions and privileges in regard to land—granted during this period strengthened the position of the hereditary nobility.

The conferment of these immunities—which were very much in vogue in this period—was a special privilege of the king or someone in a position of similar authority, such as heirs apparent or regional rulers with considerable power such as those of Rohana. In general, immunities guaranteed freedom from interference by royal officers and ensured exemption from taxation. Pamunu (or paraveṇi as it was called after the fourteenth century) and divel holdings were now a conspicuous part of the tenurial system in a period when, paradoxically, there was a positive efflorescence of royal authority, in terms of its grandeur and majesty. As in the late Anuradhapura period, however, the most salient manifestation of such immunities were those granted to the monasteries. These now extended beyond the conventional rights to labour and the whole or part of the revenue of the block or blocks of land or village thus granted to the transfer of fiscal as well as administrative and judicial authority over the lands thus held. As a result, the monasteries and their functionaries came to be entrusted with much of the local administrative duties traditionally performed by the king’s officials. It would appear that some new administrative structures were developed to cope with this significant enlargement of the role of the monasteries in the social system.

The principal source of the king’s revenue in the Polonnaruva kingdom was the land tax with taxes on paddy contributing the major portion; there were smaller yields from levies on other crops. There was also the diyadada (the equivalent of the diyadedum of the Anuradhapura kingdom), the tax on the use of water from irrigation channels which no doubt yielded a very substantial income. There was, in addition, revenue from certain valuable items in the country’s external trade—gems, pearls, cinnamon and elephants—extending from a share of the profits to monopoly rights. Thus the mining of gems seems to have been a royal monopoly, which was protected by a prohibition on permanent settlement in the gem-producing districts. Individuals were permitted to mine for gems on payment of a fee. Mining was carried out seasonally under the supervision of royal officials, with the king enjoying prerogative rights to the more valuable gems. Pearl fishery too was a royal monopoly conducted on much the same basis. Finally, the king’s own lands were also a quite notable source of income for him. These taxes were collected by a hierarchy of officials. At the base of the structure were the village authorities—possibly village headmen—who were entrusted with the collection of taxes due to the king from each village; these were delivered to the king’s officials during their annual tours.

The fact that these taxes were paid partly at least in grain and other agricultural produce—which, being more or less perishable, could not be stored indefinitely by the officials who collected them—may have been a guarantee against extortionate levies on the peasantry. A tax of one-sixth of the produce was regarded as an equitable land tax, but in practice there was no uniformity in the rate of taxation, a flexibility which could often be to the disadvantage of the peasant. It is significant that Vijayab•hu I, on his accession to the throne, should have directed his officials to adhere to custom and usage in the collection of taxes, and that Ni••aṅka Malla himself claims to have reduced taxes presumably because they had become burdensome.

One of the notable features in the economic history of the period extending from the ninth century to the end of the Polonnaruva kingdom was the expansion of trade within the country. The data available at present are too meagre for an analysis of the development of this trade, or indeed for a detailed description of its special characteristics, but there is evidence of the emergence of merchant ‘corporations’, the growth of market towns linked by well-known trade routes and the development of a local, that is to say, regional coinage. Tolls and other levies on this trade yielded a considerable income to the state.

There was at the same time a substantial revenue from customs dues on external trade although the data we have are too scanty to compute with any precision the duties levied on the various export and import commodities. Sri Lanka was a vital link in the great trade routes between the east and the west, of importance in ‘transit’ trade due to her advantageous geographical location and in the ‘terminal’ trade on account of her natural products such as gems, pearls and timber. Apart from the traditional ports of the north and north-west of the island and on the east coast, those of the west coast too became important in this trade. Besides, the island’s numerous bays, anchorages and roadsteads offered adequate shelter for the sailing ships of this period.

Trade in the Indian Ocean at this time was dominated by the Arabs, who were among the leading and most intrepid sailors of the era. The large empires at both ends of the route—the unity imposed on the Muslim world by the caliphs and the peace enjoyed by China during the Tang and Sung dynasties—helped increase the tempo of the trade between China and the Persian Gulf. The countries of south and south-east Asia lying between these two points shared in this and indeed derived a considerable profit from it. Luxury articles were the main commodities in this inter-Asian and international trade and to this category belonged Sri Lanka’s gems and pearls.

The competition for this Indian Ocean trade was not always peaceful. Behind the Cōḷa expansion into south-east Asia lay a determination to obtain greater control over the trade and trade routes of the Indian Ocean. Although powerful political motives spurred them on to a conquest of Sri Lanka, the Cōḷas were always aware of the economic advantages of this—her valuable foreign trade and her strategic position athwart the maritime trade routes of the Indian Ocean. While Sri Lanka herself seldom resorted to war in defence of her trade interests, Par•kramab•hu I’s expedition against Burma, though somewhat exceptional, was nevertheless a significant demonstration of how commercial rivalry could undermine a long-standing alliance based on a common religious outlook.

Though most of the vessels used in her external trade were generally of foreign construction, seaworthy craft were built in Sri Lanka as well and are known to have sailed as far as China. Perhaps some of the latter may even have been used to transport Par•kramab•hu I’s troops to Burma.

Foreign merchants were attracted to the island because of its importance as a centre of international trade. The most prominent of the merchant groups settled in Sri Lanka were the Moors, descendants of Arab traders to the island. These Arab merchants and their agents had established settlements in south India as well, as early as the tenth century. They were a dominant influence on the island’s international trade in the period of the Polonnaruva kings, a position which they retained till the early decades of the sixteenth century when the Polonnaruva kingdom itself was no more than a memory. However, the foreign trade of that kingdom was by no means a Moor monopoly. There were other foreigners living on the island for reasons of trade, and among the more interesting of these were Cambodian bird-catchers. The feathers of exotic birds were an important item in international trade at this time.

Although trade, external as well as internal, had grown substantially in Sri Lanka during the Polonnaruva era, domestic agriculture continued to be the predominant economic activity of the kingdom. And the role of money in the economy appears to have been, as in the days of the Anuradhapura kingdom, of merely peripheral significance.

Religion And Culture

The inevitable result of the Cōḷa conquest was the intrusive impact of Hindu-Brahmanical and Saiva religious practices, Dravidian art and architecture and the Tamil language itself on the religion and culture of Sri Lanka. The period of the south Indian invasions of the Anuradhapura kingdom in the ninth and tenth centuries coincided with the decline of Buddhism in India and the collapse of important centres of Buddhist learning as a result of Muslim invasions. These processes proved to be irreversible. South Indian influence on Sri Lanka thereafter became exclusively Hindu in content.

It is against this background that the recovery of Buddhism under the Polonnaruva kings needs to be reviewed. The most substantial contributions came from Vijayab•hu I and Par•kramab•hu I. The unification of the sangha in the latter’s reign was one of the most significant events in the history of Sinhalese Buddhism. Traditionally, this has been viewed in terms of the triumph of the Mah•vihara, and the discomfiture if not suppression of the Abhayagiri and Jetavana nik•yas. But recent research has shown this to be quite inaccurate. The loss of property by the monasteries during the period of Cōḷa rule, and again in the interregnum between Vijayab•hu I and the accession of Par•kramab•hu I had had a deleterious effect upon all the nik•yas. Their disintegration had, in fact, led to a new grouping of the sangha under eight mulas or fraternities. Par•kramab•hu I brought these eight fraternities together under a common leadership—a process of unification which was at once much more and much less than imposing the authority of the Mah•vihara over the other two nik•yas. It did not end sectarian competition, but appears to have had a tonic effect on both evangelistic and scholarly activity.19

The resuscitatory zeal of these two monarchs in particular demonstrated afresh the remarkable resilience of Sri Lankan Buddhism. Sinhalese bhikkhus maintained contacts with distant centres of Buddhism like Nepal and Tibet; they also made vigorous but unsuccessful attempts to spread their teachings in Bengal,20 apart from engaging in spirited disputes with their Theravadin colleagues in south India on questions relating to the interpretation of the canon. It was south-east Asia, however, that was most receptive to their teachings, and the expansion of Sinhalese Theravada Buddhism in that region—Burma and Thailand—was an important trend in its cultural history during this period.

Two other developments in Sri Lankan Buddhism need mention. First, there was the increasing popularity of the Ārannav•sins, the forest-dwelling monks in the latter part of this period, who gained prominence in scholarly activities and took the lead in reformist movements. Second, there was an increasing involvement of monasteries in secular activity, which stemmed mainly from the large land grants donated to the sangha and the transfer of administrative authority over the temporalities to the monasteries, a significant extension of the privileges normally implied in the immunities granted with such donations of land.

One of the distinctive features of the literature of the Polonnaruva period was the continued vitality of Pali as the language of Sinhalese Buddhism. The tradition was still very much in favour of writing in Pali rather than Sinhala. The Pali works of this period were mainly expositions or summaries of works of the Pali canon. There were also the tīk•s explaining and supplementing the commentaries composed in the Anuradhapura era. The D•thavaṁsa, a history of the tooth relic, was one of the more notable literary contributions in the Pali language. Its author, Mah•n•ma, is also credited with the first part of the Cūlavamsa, the continuation of the Mah•vaṁsa. The Pali literature of this period bears the impression of the strong stimulating effect of Sanskrit, which had a no less significant influence on contemporary Sinhala writing. The bulk of the Sinhala works of this period are glossaries and translations from the Pali canon. There were also two prose works by a thirteenth-century author, Gurulugomi, the Am•vatura and the Dharmapradīpik•va, of which the former was more noteworthy; and two poems (of the late twelfth and early thirteenth century), the Sasad•vata and the Muvadevad•vata, both based on J•taka stories, and both greatly influenced by the Sanskrit works of K•lid•sa and Kum•rad•sa.

The literature of the Polonnaruva era that has survived is neither substantial nor exceptionally distinguished. Indeed, all of it shares the flaws of the literature of the Anuradhapura period without its compensating virtues, and they do not compare, in creativity or originality, with the writings of the succeeding period of Sri Lanka’s history.21

In architecture and sculpture the performance was memorable. Apart from the restoration of ancient edifices, Vijayab•hu I’s major contribution was the construction of the Temple of the Tooth (now represented by the ruin called the Atad•gē). There was a considerable setback to this artistic recovery in the instability and turmoil that followed his death. With Par•kramab•hu I the great period of artistic activity of Polonnaruva began, and was continued under Ni••aṅka Malla during the brief decade (1187–96) of order and stability which his reign represented and during which Polonnaruva reached the zenith of its development as a capital city.

The Gal Vihara sculptures (in the reign of Par•kramab•hu I) are the glory of Polonnaruva and the summit of its artistic achievement. The four great statues of the Buddha which comprise this complex, representing the three main positions—the seated, the standing and the recumbent—are cut in a row from a horizontal escarpment of streaked granite. Each of these statues was originally sheltered by its own image house. The consummate skill with which the peace of the enlightenment has been depicted in an extraordinarily successful blend of serenity and strength has seldom been equalled by any other Buddha image in Sri Lanka. Of similar nobility of conception and magnitude is the colossal figure (of a sage, as some scholars would have it, or a monarch, as others insist) overlooking the bund of the Tōp•väva. The dignity, puissance and self-reliance of the figure have been rendered with amazing economy and restraint.

Sage, Polonnaruva

Of the architectural monuments attributed to the reign of Ni••aṅka Malla the most unforgettable is the collection of temples and viharas in the so-called Great Quadrangle, which has been described as among the ‘most beautiful and satisfyingly proportioned buildings in the entire Indian world’.22 The Ni••aṅka-lat• mandapaya is a unique type of Sinhalese architectural monument: a cluster of granite columns shaped like lotus stems with capitals in the form of opening buds, within a raised platform, all contributing to a general effect ‘of extreme chastity and Baroque fancy [unsurpassed] in any Indian shrine’.23

Buddha image, Gal Vihara, Polonnaruva

The Hätad•g• was certainly begun and completed during Ni••aṅka Malla’s reign. The embellishments on the pillars ofthe Atad•gē have no rival in the decorative art of the Sinhalese, and stand comparison with the best examples of such work elsewhere. The beautiful vatad•gē, ‘one of the loveliest examples of Sinhalese architecture,’24 has its name associated with Ni••aṅka Malla but it is doubtful if he did much more than construct its outer porch. The Satmahalpr•s•da and the stupendous Rankot Vihara (or, to give its ancient name, the Ruvanväli), with the frontispieces and chapels at its base, were the work of Ni••aṅka Malla.

Buddha image, Gal Vihara, Polonnaruva

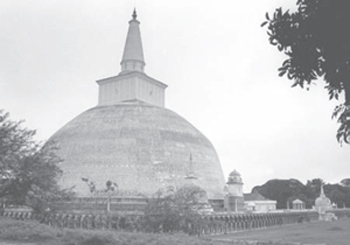

Ruvanvelisaya as it is today

Although there is a striking continuity between the art and architecture of Polonnaruva and that of Anuradhapura, the distinctive feature of Polonnaruva’s architectural remains is the mingling of Buddhist and Hindu decorative elements, a fusionwhich extended far beyond the mere stylistic plagiarism of Hindu and Dravidian forms. It reflected the powerful influence of Mahayanism and Hinduism in the lives of the people.

Tisawewa, Anuradhapura

Twin ponds, Anuradhapura

Siva dēv•lē No. 2 is the earliest in date of all the monuments now preserved in Polonnaruva. Built entirely of stone, it datesfrom the time of Cōḷa rule and is a representative example of Dravidian architecture at its best. Later in date and more ornate is Siva dēv•lē No. I. Both are smaller, one might even say miniature, versions of the towering Cōḷa architecture of south India.

The Satmahalpr•s•da, a stupa with an unusual pyramid-like form in seven levels or storeys, is much more of an enigma. Was this monument yet another derived from an Indian prototype25 or an outstanding example of south-east Asian—Cambodian and Burmese—influence on Sri Lankan architecture? The latter seems more likely because of the peculiar shape of this monument and in view of the very close religious ties at this time between Sri Lanka and the Buddhist countries of south-east Asia.26

As at Anuradhapura, few secular buildings have survived in Polonnaruva. Of Par•kramab•hu’s palace only the foundations remain today, but Ni••aṅka Malla’s audience hall is in a better state of preservation.

As for painting, what is now preserved is a very small fraction of the work executed by the artists of the Polonnaruva kingdom. Of the secular paintings nothing has survived, although the evidence suggests that the walls of palaces—like those of shrines—were decorated with paintings. Those on religious edifices have fared slightly better. The Lank•tilaka bears traces of paintings on both its exterior as well as interior walls. The walls of the Tivaṅka-pratim•ghara (erroneously called the Demalamahasäya) carry more paintings than any other monument at Polonnaruva or indeed on the island, but the date of these paintings is a matter of conjecture, for though this shrine was built in the reign of Par•kramab•hu I, it has evidently been renovated and possibly altered at a later date.

These paintings are the work of artists who had centuries of tradition behind them and who belonged to a school which, in its heyday, had ramifications throughout the subcontinent of India and beyond it. The famous cave paintings of Ajanta and Bagh are its most mature products. By the twelfth century, this artistic tradition was almost extinct in India, but the fragmentary remains of the Polonnaruva paintings afford proof that it had been preserved in Sri Lanka long after it had lost its vitality in the land of its origin. Nevertheless, like the earlier Sigiri paintings, these latter are distinctly provincial in comparison with the Indian prototype.

Indeed, all the later work in Polonnaruva, whether in art or architecture, appears archaic if not atavistic, the result very probably of a conscious effort at reviving and imitating the artistic traditions of the Anuradhapura kingdom. The moonstones of Polonnaruva are inferior to those of Anuradhapura in vitality and aesthetic appeal, just as the baths which adorned the palaces and monasteries were smaller in size and, with the single exception of the exquisite lotus bath, less elegant in design.

The transformation of Polonnaruva into a gracious cosmopolitan city27 was the work of three kings—Vijayab•hu I, Par•kramab•hu I and Ni••aṅka Malla. This development could be measured in generations if not decades and not, as in the case of the cognate process in Anuradhapura, in centuries. Polonnaruva had a smaller area than Anuradhapura, but its compactness was conducive to a remarkable symmetry in the location of its major edifices, all of them like so many links in some gigantic creation of a celestial jeweller who used the Par•krama Samudra to the best possible advantage to set them off.

The comparatively short period in which the architecture and sculptural splendours of Polonnaruva were created is no doubt testimony to the dynamism and creativity of its rulers and people. But it had its sombre side as well, for in retrospect the activity seems febrile, and this conspicuous investment in monuments must have impaired the economic strength of the kingdom and contributed greatly to the rapid decline that set in after the reign of Ni••aṅka Malla.