21

An Era of Reform and Reconstruction, 1833–50

The reformist zeal generated by the Colebrooke-Cameron reforms and a passion for change affected every sphere of activity—political, economic and social—for nearly two decades. Never before, and seldom thereafter under British rule, was there the same warm support in official circles for policies designed to transform society.

Social Reform

The most powerful influence on the social policy of this period was religious sentiment. This was partly due to evangelical influence (mainly through James Stephen) at the Colonial Office, men like Governor Stewart Mackenzie (1837–41) and a host of subordinate officials in Sri Lanka who believed in the urgency of converting the ‘heathen’ to Christianity. It was also partly due to the agitation of missionary organizations for a redefinition of the relationship between Buddhism and the colonial government on the island.1 During his brief tenure of office as Secretary of State for the Colonies in the late 1830s, Lord Glenelg had laid it down that the conversion of the people to Christianity should be a vital aspect of state policy in Sri Lanka. His successors during this period shared this belief to a greater or lesser extent. The new policy naturally implied active state support of missionary enterprise and it was significant that the state supported all Christian missions on the island alike. The determined application of this policy resulted in bitter sectarian strife, because the Anglicans fought tenaciously in defence of their privileged position in education, the registration of births, marriages and deaths, and state-subsidized church construction.

In Sri Lanka at this time, missionary organizations were the dominant influence in education. The medium of instruction in most schools was the English language, and with the ‘filtration theory’ very much in vogue, the aim was to educate the elite. It was accepted without question that education should aim primarily at conversion to Christianity. Not the least significant of Mackenzie’s achievements was his success in breaking the hold of the Anglican establishment on the school commission. He was less successful in his attempts to have the vernaculars used in instruction in schools and to bring education to the masses, both of which challenged the current orthodoxies on education in the eastern empire and were for that reason rejected by the Colonial Office. But in the years 1843–48, one aspect of Mackenzie’s policies, vernacular education, was officially adopted mainly because of the tactical skill and administrative ability of a Wesleyan missionary, the Revd D. J. Gogerly. Education was a sphere of state activity in which missionary influence on policy making was most marked. Had there been fewer sectarian squabbles that influence would have been even stronger.

In Sri Lanka, unlike India, there were no glaring social evils associated with the indigenous religions—no sati, thägi, meriah sacrifices, or rituals such as those of the temple of Jagannath. There was thus less scope for the social reformer. The problems that attracted attention were far less intractable than those in the Indian subcontinent. The mild form of slavery then existing on the island was gradually abolished, with the government taking the initiative in this; the state also took a paternal interest in the aboriginal Vaddas, protecting them, civilizing them and attempting to convert them to Christianity. Although the missionaries had little influence on the actual formulation of these policies (especially, that on slavery), they sympathized with and actively supported them, since they coincided with their own aims. They served as auxiliaries of the government in various projects of social reform, the Vaddah [sic] Mission of the Wesleyans being the most significant of them.

No policy of social reform could ignore the problems posed by the caste system, for caste in a sense was the most awkward impediment confronting the social reformer. Neither the administrators nor the missionaries had a clear policy on caste except a vague egalitarianism. Had there been something as morally and socially repugnant as untouchability, it might have been possible to focus attention on it and thereby compel the adoption of a positive programme of action; but untouchability scarcely existed in Sri Lanka, where caste was too amorphous to be tackled by a precise and deliberate policy. Nevertheless, at this stage the government was against caste without knowing very much about it except that it hampered their programmes of reform. They were convinced that caste was both obnoxious and intolerable and were opposed to any positive recognition of caste distinctions.

Two decisions of the government, the abolition of r•jak•riya in 1833 and the reform of the jury system in 1843, focussed attention as never before on the state’s attitude to caste. While the abolition of r•jak•riya was perhaps the most telling blow against the caste system in the first half of the nineteenth century, there was no positive declaration on that occasion explicitly directed against caste discrimination as there was in 1843–44 in the controversy over the reform of the jury system. There was a third, and no less significant, development—the appointment of non-Goyigamas as mudaliy•rs of the Governor’s Gate.2 These posts had been the preserve of the Goyigama elite and were the most prestigious positions available to a Sinhalese. In the 1840s, the Goyigama monopoly of these coveted posts was breached for the first time with the appointment in 1845 of Gregory de Zoysa, a Sal•gama. The second to be appointed was Mathew Gomes, a mudaliy•r of the washers since 1814. He was appointed in 1847 but his tenure of office was short (he was dismissed for embezzlement in 1848). These two appointments were a prelude to a more significant one—that in 1853 of Jeronis de Soysa of the Kar•va caste, the wealthiest Sinhalese of the day. The Goyigama establishment opposed the appointment and endeavoured to get the government to give de Soysa a position of lower status, namely that of mudaliy•r of Moratuva, the village from which he hailed. But Governor George Anderson, stood firm.

In no aspect of policy was the impact of evangelicalism and missionary influence felt more strongly than on the question of the severance of the connection of the state with Buddhism.3 The connection of the state with Buddhism stemmed from the terms of the Kandyan Convention of 1815. Until 1840, this association with Buddhism had been maintained without much protest, but thereafter the whole question was reopened in the wake of the successful missionary campaign in India against the connection of the East India Company with Hinduism. When pressure from missionaries for a total dissociation of the state from Buddhism emerged, the Sri Lanka government, aware of the unpopularity of any such move and fearing that this religious agitation would result in civil strife, refused to be stampeded into hasty and indiscreet action. The missionaries, however, succeeded in imposing their views on the Colonial Office where James Stephen became the ardent advocate of their contentions and where under his influence successive Secretaries of State in the 1840s called upon the colonial government to sever the state’s connection with Buddhism. The crucial policy decision with regard to this was taken by the Secretary of State, Lord Stanley, in 1844 and was reaffirmed by Earl Grey in 1847.

Despite these peremptory instructions from London, officials in Colombo were reluctant to implement this policy with the rigour and precision which the despatches (written by Stephen) called for. They had doubts about the morality of abrogating the solemn undertaking to protect Buddhism given in 1815 and reaffirmed (though less categorically) in 1818. Besides, there was the vital question of determining to whom the functions and traditional obligations of the state in regard to Buddhism should be transferred. Crucially important in this regard was the question of temple lands and the protection of the property rights of the viharas and dēv•lēs; should the severance of the state’s connection with Buddhism be effected without a settlement of this question of temple lands, the whole legal position of the temples over their lands and tenants would be undermined. Higher church dignitaries in Europe had a corporate legal status; there was nothing comparable to this in Sri Lankan Buddhism and legal enforcement of the most elementary property rights of viharas and dēv•lēs would be impossible without some form, which the courts could recognize, of accrediting an ecclesiastical dignitary or temple trustee. For a long time, however, the Colonial Office, under James Stephen’s influence, treated Buddhism as though it had a centrally organized structure akin to Christianity and did not see the need to establish such a body to inherit the state’s obligations and duties in regard to the protection and maintenance of that religion. Nor were they conscious of any moral obligation in this regard. Faced with this uncompromising attitude of the Colonial Office, the Sri Lankan officials had no alternative but to proceed apace with the dissociation from Buddhism. They took a more practical and pragmatic position, however, and endeavoured to evolve some administrative machinery to which the ecclesiastical responsibilities vested in the government by the Kandyan Convention could be transferred. Their pleas for caution and moderation fell on deaf ears; the Colonial Office under Stephen would not yield an inch. Completely convinced of the justice of his policy, he obstinately refused to recommend any concessions to the Buddhists on this matter.

The Transformation Of The Economy

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of the 1840s was the invigorating effect which the success of plantation agriculture, especially coffee4 culture, had on the economy of the colony. A period of experimentation in plantation crops began in the mid-1830s and within fifteen years the success of one of the crops, coffee, had radically changed the economy. There were, in the late 1830s, two centres of coffee cultivation on the island—the Udugama Hills about 26 km from Galle, where several Colombo-based commercial houses had opened coffee plantations, and Gampola, Peradeniya and Dumbara in the Kandy district. The Galle ventures failed, but the Dumbara plantations were a pronounced success and even more of a breakthrough to sound commercial profitability than those at Gampola and Peradeniya. The effect of the proven viability of the Kandyan plantations was the suspension, to a large extent, of planting operations in the Southern Province. The Central Province, the heartland of the old Kandyan kingdom, was henceforth the focus of plantation activity.

In the six years from 1838 to 1843 no fewer than 130 plantations were opened up in the Central Province, almost all of them in districts within 50 km of Kandy. By 1846, there were between 500 and 600 coffee plantations on the island, the great majority of them in the Central Province. Indeed the area under coffee nearly doubled between 1 January 1845 and 31 December 1847, from 10,205 hectares to 20,278 hectares.5 Knowledgeable contemporaries estimated that nearly £5 million was invested in coffee, both by individuals (many of whom operated on the proverbial shoestring) and by agency houses. The stimulus to this unrestrained expansion of cultivation (‘the coffee mania’, as it came to be called) was provided by a steep rise in the consumption of coffee in Britain and western Europe and, to a lesser extent, the protection afforded to colonial as against foreign coffee in the British market.6

A fall in coffee prices in 1845 jolted the more perceptive investors and planters into a more realistic assessment of the industry’s prospects. Nevertheless, it did seem as though economy and retrenchment could stabilize the island’s coffee industry. Commercial credit was still relatively sound and capital was still forthcoming to support coffee properties in this period of trial, although it was already apparent that a large amount of capital was buried in the soil with little prospect of recovery. The island’s coffee industry might have held its own, had not the commercial crisis of 1847–48 in Britain intervened. The depression in Britain set in motion a train of events which culminated in the near collapse of the island’s coffee industry. A fall in the consumption of coffee, accompanied by overproduction, had the inevitable consequence of a sharp drop in prices. This soon revealed the inherent weakness of Sri Lanka’s apparently booming coffee industry. The coffee disaster of 1847–48 brought down the great agency house of Ackland Boyd and Company (which at the height of the coffee mania controlled as many as thirty-five plantations in the Central Province), smaller houses such as Hudson, Chandler and Company and scores of individual proprietors and small investors.

The coffee industry was nevertheless more resilient than gloomy contemporary observers anticipated. Indeed, by 1849 signs of recovery were already noticeable; in the early 1850s many of the abandoned plantations were made viable again and then new plantations were opened after confidence had been gained from the rehabilitation of the old ones. A shrewd observer of the contemporary scene pointed out that some of the new proprietors had started off with an advantage of inestimable value—during the financial crisis of 1847–48, scores of estates had changed hands at very low prices and their new owners were able to start without the crippling burden of their predecessors’ debt. But the recovery of coffee in Sri Lanka owed almost as much to improving market conditions in Britain. Although coffee prices never attained the heights reached in the spacious days before 1845, they nevertheless afforded an adequate if not substantial margin of profit, so much so that although the protection enjoyed by colonial coffee in the British market was entirely removed in 1851, it did not in any way check the recovery of the island’s coffee industry.

The extraordinary success of coffee in this period should not divert attention from the fact that it did not establish a distinct ascendancy till the mid-1840s and that plantation activity in the two decades from about 1820 to 1840 was notable for experimentation in several plantation crops in various parts of the island. In the 1820s, indigo cultivation was unsuccessfully attempted near Veyangoda in the wet zone lowlands. Between 1833 and 1843, in fact, there was every prospect that the island would have developed several agricultural industries, instead of relying exclusively on cinnamon or coffee. An attempt was made, whether consciously or not, to recreate in Sri Lanka the economic pattern of the West Indies with its emphasis on sugar and coffee as major industries and cotton and tobacco as subsidiaries. Until the end of 1845, there were as high hopes of sugar as there were of coffee. In the wet zone lowlands, sugar plantations were opened at Negombo, Kalutara and in the Galle district at Baddegama and Udugama; in the Kandyan provinces there were two centres of sugar production, one at Peradeniya and the other in Dumbara. These ventures had all failed by the mid-1840s, which contemporaries attributed to factors such as climate, soil and location. A few experimental ventures in cotton cultivation were attempted in the east of the island, in what became the Eastern Province after 1833, and on a comparatively large scale in the Jaffna Peninsula, but none of these ventures were even modestly successful to attract the attention of European capitalists at this time. Indeed, cotton culture never really got going. There was, in fact, a very limited amount of capital available for investment in Sri Lanka’s plantations, and this capital tended to concentrate on the one successful enterprise, coffee.

Contemporary with this there was a parallel development—the decline of the cinnamon industry, till then the staple of the island’s export economy. The speed with which the abolition of the cinnamon monopoly was effected in the early 1830s introduced an element of uncertainty and instability into an already declining industry. Besides, the British Treasury, calculating that the implementation of Colebrooke’s recommendations would result in a fall in government revenues, insisted on the imposition of an export duty of 3 shillings a pound of cinnamon, which had the most disastrous consequences, for it quickly made the island’s cinnamon practically uncompetitive in foreign markets. Pressure from the colonial government and the cinnamon trade led to reductions of this duty in 1841 (to 2 shillings a pound), 1843 (to 1 shilling) and 1848 (to four pence) and the duty was finally abolished in 1855. But every reduction in duty had failed to make cinnamon competitive with cassia (Cassia lignea), a cheap substitute which was capturing an increasing share of the market. Every reduction of duty had come too late. Had more capital been pumped in and more scientific techniques of production been used, the cinnamon industry might have recovered much earlier than it eventually did. Colebrooke, however, even as late as 1840, was convinced that cinnamon could remain the staple of the island’s economy and continue to yield a substantial revenue to the state. But in the early 1840s few were inclined to invest in an obviously declining cinnamon industry when coffee yielded such high profits. Cinnamon never recovered the position it enjoyed in the years before 1833; it survived as a minor crop controlled by Sri Lankan plantation owners and smallholders and was subject to widely fluctuating market conditions.7

Thus, by the mid-nineteenth century, there was every appearance that the island’s economic development in the immediate future would be characterized by monoculture in its plantation sector, for only coffee had survived and only coffee gave promise of permanent success. But the overwhelming predominance of coffee as a plantation product did not survive for long. By the 1860s, coconut had emerged as a plantation crop with a great potential for expansion. Indeed, European planters had begun to cultivate coconut on a commercial scale from the early 1840s; the early plantations were located in the Jaffna Peninsula and on the east coast near Batticaloa, with a few properties in the south-west as well. However, the depression of the late 1840s put a severe brake on the extension of coconut cultivation and it was not till the early 1860s that production began to expand again.

One other feature of the economic development of the island in the 1830s and 1840s did not survive into the mid-century. Prominent among the pioneers of planting enterprise were British civil servants (and military officials) stationed on the island. These men were there on the plantations because Colebrooke, with amazing lack of foresight, had reduced their salaries, curtailed many of their financial privileges (including their right to an attractive pension) and eliminated many avenues of normal promotion, while encouraging them to engage in plantation activity. And very soon they were paying attention to their plantations to the neglect of their official duties. The decline in civil service standards and morale became a persistent theme in official despatches to and from Colombo in the early 1840s. But purely from the point of view of economic development, the civil servants of this period served a useful if somewhat unusual function as pioneer planters at a time when there were few entrepreneurs either among the small band of Europeans resident on the island or among the local inhabitants. The civil service reforms of 1844–45, in which Anstruther, Colonial Secretary of the Sri Lanka government and a pioneer coffee planter himself, played an important role, put an end to the civil servants’ involvement in trade and plantation agriculture.

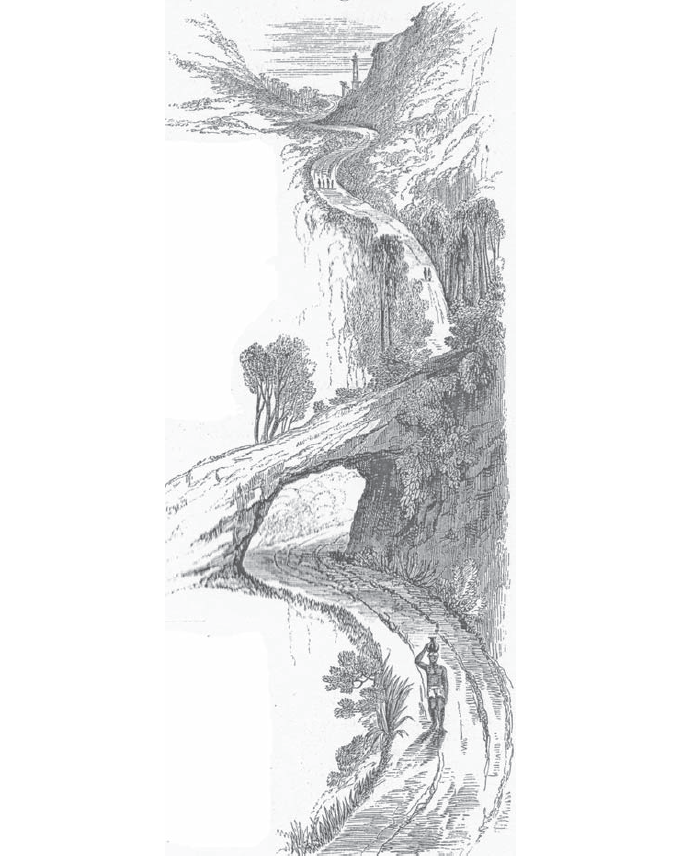

But several features of this phase of plantation activity survived into the second half of the nineteenth century. There was, for instance, the close reciprocal relationship between the expansion of plantations and the growth of communications. One of the vital preliminary steps in this relationship was the development of the road linking Colombo to Kandy. This was open to rough cart traffic by 1823 and fully bridged and completed by 1832. Although undertaken primarily for administrative and strategic (that is, political) reasons, this vital link came to have great economic advantage. Several roads were undertaken or sponsored by the government in response to the needs of the plantations and these roads in turn enabled the extension of coffee cultivation into new regions. Next there was the crucially important role of the agency houses, both in their managerial function and as credit institutions. The early planting enterprises, whether individual proprietors or partnerships, had little capital of their own and were dependent on outside sources of capital to a remarkable extent. Many of the small capitalists who purchased land in the early 1840s were only able to carry on by borrowing money from England or Colombo through agency houses.

Producers of coffee were confronted with the fact that it took nearly a year between the harvesting of the annual crop and its sale in London for them to get the money for the coffee exported. Again, although wages were generally low, the volume of current expenditure in coffee estates was nevertheless large and consumed a significant portion of the money available. Also, coffee was more vulnerable than other crops to variations in rainfall and, therefore, coffee production involved unusual risks: since the crop for the whole year was often dependent on the weather during a single month, a week’s—or a day’s—untimely or unseasonal rain might well destroy the chance of an adequate return for a whole year’s labour. Apart from these hazards, fluctuating exchange rates and delays and difficulties in shipping posed formidable difficulties for those engaged in plantation agriculture at this time. British commercial banks were generally reluctant to purchase long-term securities, or to advance money on land or fixed equipment, because they regarded foreign plantations as ‘the most objectionable of all fixed securities’. As a result, the agency house became almost the only source of liquid capital funds for the plantations. In sharp contrast to their principals in London, the agency houses regarded plantations as good investments. The fact is that their loans to planters on the security of plantations, factories and even crops were relatively safe ventures whereas they would have been quite unsafe for a bank. This was because of their knowledge of every circumstance connected with the markets and the power of superintendence which they often retained.

Road to Colombo from Kandy through Kadugannawa Pass

—Nineteenth Century. Source: Ceylon by Emerson Tennent, Vol II.

Nothing was more exasperating to the British planters in Sri Lanka at this time than the fact that with the great majority of their plantations established in the old Kandyan kingdom, they were still as dependent on immigrant Indian labour as their contemporaries in the West Indies or Mauritius. A pioneer coffee planter explained that the Kandyans had no incentive to work on the plantations:

They have, as a rule, their own paddy fields, their own cows, bullocks, their own fruit-gardens; and the tending and managing of these occupy all their attention. Their wants are easily supplied, and unless they wish to present their wives with a new cloth, or to procure a gun or powder and shot for themselves, they really have no inducement to work on the coffee plantations.8

There were other reasons. A more perceptive observer commented:

The [Kandyan] has such a reverence for his patrimonial lands, that were his gain to be quadrupled, he would not abandon their culture.... Besides, working for hire is repulsive to their national feelings, and is looked upon as almost slavery. They being obliged to obey orders and to do just what they are commanded is galling to them.9

The substantial immigration of Indian labourers to work on the coffee plantations of Sri Lanka began in the 1830s and increased to a regular flow in the early 1840s. These immigrant workers formed part of the general movement of Indians across the seas to man the plantations of the second British empire. In many ways—and largely because of the close proximity of the island to India—the movement of plantation workers to Sri Lanka differed considerably from that to the other tropical colonies, in that it was seasonal. The coffee plantations unlike the tea and rubber plantations of the future, did not require a large permanent labour force. The demand for labour reached its peak during the coffee-picking season, generally mid-August to November. Since this coincided with the slack season on the rice fields of south India, peasants from there were able to make an annual trip to Sri Lanka to work on the plantations and return to their homes in time for the next harvest.

At every stage the immigration from India to the West Indies and Mauritius was rigidly controlled and carefully supervised by the imperial government, the East India Company in India and the receiving territories. To a large extent this close supervision was the result of agitation in England and India by evangelical groups.10 The gravity of the problems involved in the transition from slave to free labour compelled these governments to intervene in a sphere of activity which the conventional wisdom of the day placed outside the scope of the state’s legitimate functions.

Faced with agitation from the planters on the island for the adoption of a policy of state-sponsored and state-subsidized immigration of plantation labour on the model of Mauritius and the West Indies, the government urged that there was a significant difference between those examples and the immigration of Indian labour to Sri Lanka. The latter, they insisted, was more akin to the seasonal immigration of Irish agricultural labourers to England. The government’s policy was to leave the importation of labour to the planters themselves, who in their turn left the business in the capable but unscrupulous hands of Indian recruiting agents—the kang•nies—from whom a system of private enterprise in the provision of immigrant labour, generally on a seasonal basis, developed. It was inefficient and, above all, led to a heavy death toll, not indeed from any unusual rapacity on the part of planters and recruiting agents but largely because of the perils of the trek from the coast to the plantations through malaria-infested country.

The rapid expansion of plantation agriculture created an unprecedented demand for wastelands. With several senior civil servants actively engaged in plantation agriculture and predisposed to help the planters, the urgency of the need to provide land for the expansion of capitalist agriculture was appreciated with greater alacrity than it otherwise may have been. Up to 1832, wastelands at the disposal of the Crown were allotted on the land grant system, the practice prevailing in all parts of the empire at this time.11 The Crown lands in each colony were virtually at the disposal of the governor and through him of the administration in the colony. This system was inefficient and economically wasteful and it had in addition the disadvantage of breeding local vested interests which, in many colonies, resisted all attempts at reform. The Colonial Office was at this time intent on simplifying and systematizing land sales procedure in the colonies and on imposing a measure of uniformity in these matters in all parts of the empire. The guiding principles behind this uniformity were provided by the theories of Edward Gibbon Wakefield. In Sri Lanka, however, the applicability of Wakefieldian theory was limited by the fact that the island was never looked upon as a settlement colony proper. Nevertheless, on the initiative of the Colonial Office, Wakefieldian dogma was introduced into the island in the more limited sphere of land sales policy. By 1833, the principle of selling Crown lands by auction, as well as the idea of a minimum upset price were introduced and the land grant system was abolished. The minimum upset price was 5 shillings an acre as in the Australian colonies. The adherence to a precisely defined upset price generally applicable to all lands in the colony was prompted by faith in one of the cardinal tenants of Wakefieldian theory, namely, that the price of land should be a restriction sufficient to adjust the supply of land to the supply of labour. The minimum upset price was expected also to deter speculators and to afford encouragement to capitalists, usually with limited means, who were intent on immediate development.

Land sales policy in Sri Lanka was motivated by the need to create a land market for the purpose of plantation agriculture. But while the planters wanted land as cheaply as possible, they also wanted clarity of title, fixity of tenure and a precise definition of the rights of ownership, all of which were essential requirements for their commercial transactions, but which were alien to the traditional practice of the local population, who only understood the age-old ‘rights’ and practices of land use. Ordinance 12 of 1840 sought to provide some at least of those requirements of modern commerce and land tenure, above all to establish the point that the Crown had ‘a Catholic right to all the lands not proved to have been granted at an earlier period’. This was no more than a projection into an oriental situation of contemporary European concepts of feudal society in general and Crown overproprietorship of land. That this theory was rather convenient—and profitable—was another of its attractions, for it must not be forgotten that every single official involved in the actual preparation and amendment of this ordinance had a stake in the coffee industry and some of them earned a measure of notoriety as land speculators. Ordinance 12 of 1840 was clumsily drafted and required amendment almost immediately. But the amending Ordinance 9 of 1841 did not succeed in clarifying all the ambiguities and by administrative order (which was not embodied in legislative enactment) the interpretation of the ordinance was modified to the benefit of inhabitants of the Kandyan districts, thus softening to some extent the impact of the original ordinance in which the advantages were overwhelmingly with the Crown in the definition of title to land. However defective it may have been as a legal instrument for the purposes which it was introduced to serve, this ordinance still did not prove an obstacle to the creation of a land market adequate for the purpose of a rapidly expanding plantation system. And this, for the planters, was the main point.

By 1843, the revitalizing effect of the coffee boom was evident in the marked improvement in the government’s revenue. The increase in the receipts from customs dues,12 though notable in itself, was clearly overshadowed by a phenomenal rise in the revenue derived from the sale of wastelands for plantation agriculture. With the colony fast outgrowing its revenue system, the Colonial Office by 1845 was in the mood for reforms in this sphere. But it was not till the end of 1846, and in the shadow of a devastating slump, that the first substantial changes in the revenue system after the extraordinary success of coffee culture in the island were planned by J. E. Tennent, the colonial secretary of British Ceylon, in his path-breaking Report on the Finances and Commerce of Ceylon. These were altogether more radical and systematic than those conceived in 1845 by the Colonial Office, or indeed by Colebrooke in 1833. They reflected also the new mood in Whitehall where Earl Grey, as Secretary of State for the Colonies (1846–52), was intent on removing ‘restrictions from industry’ and ‘securely establishing a system of free trade throughout the empire’. The island’s revenue system was dominated by indirect taxes (export and import duties); and, in sharp contrast to the position in British India, land taxes were of peripheral significance. What Tennent recommended was in effect a version of the British Indian revenue system with a land tax as its mainstay. Export and import duties were to be either totally abolished or sharply reduced and foreign imports were to come in on the same terms as British goods.

Tennent’s report, however, could hardly have appeared at a worse possible time. The recession of 1846 had become by 1847 a severe depression. With the coffee industry facing a grave crisis and cinnamon seemingly irretrievably ruined, the new governor of the colony, George Byng, Viscount Torrington, chose more cautious and conventional measures than the introduction of a land tax. The government proceeded to impose a series of new taxes which bore heavily on the peasants and the rest of the local population. Of these, the most significant was the Road Ordinance which became what Tennent’s land tax was to have been, the pivot of the colony’s new revenue system. All these taxes were vexatious and irritating in their impact on the people, and save in the case of the Road Ordinance, did not even have the advantage of yielding a substantial income. The latter, however, was viewed by the people of the Kandyan areas as an attempt to revive r•jak•riya in a most obnoxious form—compulsory labour for road construction—for the benefit of the planters.

A blend of the visionary and the practical, Tennent’s reform proposals were formulated on the basis of a critical evaluation of available data and on the basis also of a coherent theoretical framework. Torrington’s measures on the other hand, were ad hoc devices contrived not so much to reform the revenue system as to cope with the urgent problem of bridging a budget deficit. If one sees this change of focus and reordering of priorities as evidence of flagging reformist energies, these latter were totally exhausted in the political crisis of the minor rebellion that erupted in 1848. The parliamentary committee of inquiry that followed the 1848 rebellion saw the end of an era of reform which began with the Colebrooke-Cameron reforms.

The ‘Rebellion’ Of 1848

There were two centres of disturbance in 1848, one—on a minor scale—in Colombo and the other in the Kandyan provinces at M•tale and Kurunegala. The fact that in the Kandyan provinces the ‘rebellion’ occurred in regions where plantation activity was widespread prompted many contemporary observers to suggest a causal connection between the spread of plantation agriculture and the outbreak of the ‘rebellion’. As a result, the impact of the plantations on the Kandyan region (a theme which had hitherto been ignored) became—in the wake of the ‘rebellion’—a matter of serious concern among officials, as also did the innovative tendencies inherent in a policy that placed so much emphasis on plantation agriculture to the neglect of peasant agriculture.

However, the stresses created by the rapid development of plantation agriculture could not by themselves have caused the eruption of 1848. It has been argued that the plantations and British land legislation of the 1840s resulted in the equivalent of an enclosure movement and their consequences—the disintegration of the peasant economy and landlessness among the peasantry—culminated in the events of 1848. This hypothesis has a facile plausibility which up to very recent times has given it a currency and standing which it hardly deserves. The impact of the plantations was less destructive of the traditional economy at this time than the ‘orthodox’ theory would have us believe, when the land legislation did not lead to any great expropriation of peasant landholdings and landlessness was not a serious problem.

If coffee had thrived on the mud lands required for paddy cultivation and if plantation agriculture had succeeded in establishing itself in the lowlands of the densely populated Southern and Western Provinces, the confrontation between the planters and the peasants might well have been both prolonged and violent. But coffee failed in the latter regions and established itself eventually in the hills of the more sparsely populated regions of the Central Province, where it was planted on the hillsides away from the mud lands in the valleys.

It is not that there was no friction between the peasants and the planters in the Kandyan region, especially with regard to village cattle trespassing on plantations and the use and sale of wastelands in the periphery of villages. Perceptive observers had noted the gradual disintegration of the traditional society in many parts of the old Kandyan kingdom after the consolidation of British rule there and undoubtedly the breakdown was accelerated after the 1830s with the juxtaposition of the commercial economy of the plantations and the traditional subsistence economy of the peasants. One of the symptoms of the resultant malaise was an increase in crime. Equally significant was the fact that much of the crime and lawlessness was due to low-country settlers (and to a much smaller extent, Indian immigrant labourers) who had been drawn there by the economic opportunities provided by the plantations. A contributory factor, and one which attracted considerable notice, was the excise policy of the British government which encouraged the opening of taverns in the Kandyan areas, especially in the plantation districts, a region noted for the social disapproval accorded to drunkenness. But the plantations did no more than aggravate more material grievances which accounts for the very significant fact that few plantations were attacked by the Kandyans in 1848 although they offered such tempting and vulnerable targets. Of these more substantial grievances, the Buddhist policy of the British government—the attempt to dissociate the state from its formal connection with Buddhism—served to alienate the aristocracy and the sangha, the two most influential groups in Kandyan society. As the natural leaders of Kandyan opinion they looked upon this as a gross betrayal of a solemn undertaking given at the cession of the Kandyan kingdom. The estrangement of the elite might have been less harmful to British interests at a time of crisis if the people at large had been satisfied with British rule; but the British had done little or nothing for the peasants in the Kandyan areas, a neglect which stemmed from an excessive concentration on plantation agriculture. The result was that every segment of the Kandyan population either nursed a sense of grievance against the British administration, or had no positive reason to give it their support.

A scare of rebellion in 1842–43 had brought these issues, and the Kandyan problem in general, into the limelight. A pretender (or pretenders) to the Kandyan throne had appeared on that occasion, but as a result of leakage of information the threatened outbreak was nipped in the bud. These incidents should have provided ample evidence of a widening gap between the administration and the people, but even if the alarming implications of this dawned on the more intelligent civil servants, little heed was paid to these symptoms. For one thing, the officials concentrated their attention too exclusively on the beneficial effects anticipated from the success of coffee cultivation. This was much more than a matter of self-interest on the part of civil servants with plantation investments to protect. The common assumption, even among those who had no such investments, was that the plantations would be the catalyst of modernization, the basis of a buoyant economy, and that these advantages far outweighed any unpleasant side effects. That the state had a reciprocal obligation to give some minimal protection to the interests of the peasants on the issue of land sales was not accepted. This would have served to create the impression among the Kandyans that the civil servants were hardly likely to be impartial arbiters in any confrontation that may have developed between the planters and the peasants.

The government had done little for the peasants. Peasant agriculture was on the decline and the bulk of the irrigation works, not merely in the Kandyan areas but in the Southern Province too, were in a sad state of neglect and disrepair till the end of the 1850s. It was natural, therefore, for the peasants to conclude that they were faced with a most unsympathetic administration and one totally unconcerned with their welfare. It is important, however, to remember that the blame for the neglect of peasant interests in the question of land sales does not lie with the planters or with the government only. The Kandyan headmen were equally to blame. Without their connivance, if not support, land in the periphery of villages could not have been declared Crown property. The evidence suggests that the Kandyan peasants suffered as much from the machinations of corrupt Kandyan headmen, who were in the best position to understand and manipulate the new situation, as they did from the indifference and neglect of British officials.

The opportunity afforded by the events of 1842–43 for reappraisal and reassessment of current policies and attitudes was thus missed. When, in July and August 1848, widespread opposition emerged to Torrington’s taxes, the administration was caught unawares. It confronted much the same combination of forces that had been at work in 1842–43. But now these forces were stronger and better organized and intent on channelling this widespread discontent into a foolhardy attempt to rid the Kandyan regions of the British presence. The leaders did not belong to the traditional elite but were of peasant stock, some of them hailing from the low country. Their aim was a return to the traditional Kandyan pattern of life, which they aspired to resuscitate by making one of their own king. The force that inspired these men was the traditionalist nationalism of the Kandyans, a form of nationalism poles apart from that of the twentieth century, but still nationalism for that.

Two points concerning the rebellion of 1848 need emphasis. One of these is the contrast with the Great Rebellion of 1817–18. This earlier rising was the nearest approach to a ‘post-pacification’ revolt that developed, a great crisis of commitment which affected the community at large. The ‘rebellion’ of 1848, on the other hand, was confined to a much narrower region of the country and never involved the community at large to anywhere near the same extent as the Great Rebellion. This might be explained partly at least by the swiftness with which it was put down, and this in turn was due to the roads which had been originally built for precisely such a contingency as this. The second point is even more interesting. The riots of 1848 were by no means confined to the Kandyan region. There was an urban disturbance in Colombo and here, for the first time, a deliberate attempt was made to introduce into Sri Lanka society the current ideas of European radicalism. It is curious, however, that precisely such a fusion—‘Sinhalese traditionalism’ and radical ideology borrowed from Europe—made the mass nationalism of the years around 1956 so potent a force. A century was to pass before the fusion was attempted and when it succeeded few turned back to memories of 1848, when the two forces had appeared together for the first time, as movements with some likeness but with no mutual connection.

One of the immediate consequences of the ‘rebellion’ of 1848 was the reappraisal by the British government of its Buddhist policy largely because it was recognized as having contributed to the alienation of the Kandyan aristocracy and the bhikkhus, the natural and traditional leaders of Kandyan opinion: their fears for the safety of Buddhism had affected other classes of Kandyan society. After the rebellion there was a reluctance to proceed further with that policy for fear of aggravating the sense of grievance that prevailed among the Kandyans. Further, the departure of Stephen no doubt facilitated the conversion of the Colonial Office to the view that the policy of complete dissociation from Buddhism was ‘not consistent with the spirit of our engagements to the people of Ceylon...’. Thus after 1848 the Buddhist policy of the Colonial Office became noticeably less rigid and evangelical than it had been before. Although still insisting on a dissociation of the state from Buddhism, it conceded that there was an obligation to initiate and supervise the performance of specified legal functions, especially with regard to the Buddhist temporalities. The missionaries were dissatisfied with this compromise, but the Colonial Office backed Governor George Anderson, in his policy of moderation.

Although the compromise settlement of 1852–53 was unsatisfactory from the missionaries’ point of view, it was nevertheless true that they had won a significant victory, for they had, through the controlled application of pressure, brought the age-long connection of Buddhism with the rulers of Sri Lanka to an end. Their triumph was the more significant for having been won in spite of the resolute opposition of the Sri Lankan government. It was also the only issue on which the missionary groups showed any sort of unity.