I do not know what, if anything, the Universe has in its mind, but I am quite, quite sure that, whatever it has in its mind, it is not at all like what we have in ours. And, considering what most of us have in ours, it is just as well.

—Ralph Estling, The Skeptical Inquirer, 1993

Cannot there he found a Christian to cut off my head?

—Emperor Constantine XI Palaeologus, May 29, 1453 |

|

“I don’t like this one bit,” Mr. Plex says as he gazes up at some Greek statues and dusts himself off.

Hercules’ esophagus is evaginating through his mouth, and Aphrodite’s head looks like a moose.

You gaze down at the remains of the large centaur statue that had crashed down upon Mr. Plex’s back. “Thank you, Mr. Plex, for saving my life.”

“It was nothing, sir. My diamond body can withstand a thousand times that weight.”

Theano shudders. “What’s happening?” she says. “We’ve had minor earthquakes around here, but nothing like that.”

You walk closer to her. “Time travel is always risky. Especially when the transfinites are watching.”

“Transfinites?”

You nod. “They’re angry with us and causing all this mischief with the statues.” You pause when you see a confused expression on the faces of Mr. Plex and Theano. “They’re a race of advanced beings who don’t like us traveling back to the past. I guess they want to scare us. The further back we travel in time, the more angry they seem to get.”

“What about the crustaceans, sir?”

“They’re the ‘keepers of time.’ Whenever the transfinites break through to try to scare us back to the future, the shrimp try to repair the crack in time. But there’s no need to worry. We’ll have another week before we really have to get the hell out of here.”

Mr. Plex is breathing rapidly. “Sir, where do transfinites come from?”

“The Tarantula Nebula. It’s a mix of gas and dust in the Large Magellanic Cloud, one of the Milky Way’s two companion galaxies.”

“Far away?”

You nod. “Although it’s 190,000 light-years away, you could see it with your naked eye in the Earth’s southern hemisphere.” You pause. “Somehow they’ve learned to use a wormhole in space to quickly travel the vast distances.”

Theano stretches her arms and begins to pace. “Can we get out of this room?”

You kick at some discarded hamburger wrappers. “Why not?”

“Sir—”

“It’s OK, Mr. Plex. We’ll just walk around inside the Temple.”

“But sir, we might be seen between the columns.”

“Relax, Mr. Plex.”

It is early morning. Somewhere in the distance, a lone kithara player strums a ragged, soulful song. As you gaze out from between the massive columns, the sky seems limitless, gleaming with a magical light beyond an endless terrain of hills. The scent of rain mingles with the cool breeze.

“I love the fresh air,” Theano says.

She begins to talk now and then in easy bursts, her smooth voice always charming and distracting you slightly from the content of what she says. Now Theano seems eager, happy, curious about things around her. No regrets apparently. But then it is so soon …

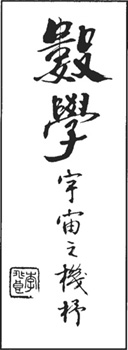

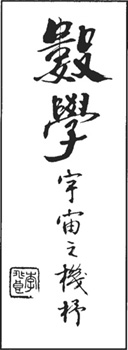

You lean upon a massive marble column and begin to draw on its surface:

XXXXX … . X X . . X . X X . X . X . . X . . X X . .

“Sir, what is it? Some kind of code?”

“Let me tell you what our agents in the year 1453 have just discovered—diabolical mathematics involving two religions. In the 1950s the scenario evolved into a game called

Turks and Christians.

Theano drifts closer. “Sounds fascinating,” she says, “but give me some background. What’s this about the year 1453?”

You nod. “The mathematical puzzle involves the concept of decimation. Throughout history, the lawful penalty for mutiny on a ship was to execute one-tenth the crew. First the crew members were forced to randomly line up in a circle. It was then customary that the victims be selected by counting every 10th person from the circle, hence the term decimation. Eventually this term has come to be applied to any depletion of a group by any fixed interval—not just ten.”

Theano appears deep in thought. Her golden tetraktys earrings glisten in the sunlight. “What does this have to do with religion?”

“A very old puzzle about decimation is called Turks and Christians. The story is that 15 Turks and 15 Christians were aboard a sailing vessel caught in a hurricane. The captain decided to appease the gods by throwing half his passengers overboard—”

“Horrible story, sir.”

“In order to leave the selection of victims to chance, the captain arranged all 30 people in a circle, and he announced to them that every thirteenth person would be killed. A clever but ruthless Christian whispered to his fellow Christians a plan on how they might be saved. He pointed out exactly how to take places in the circle so that only 15 Turks would be counted and thrown overboard.”

“Sir, is that possible?”

Theano whispers, “Why did the Christians hate the Turks?”

“Perhaps because the Turks killed the Christian emperor Constantine XI Palaeologus in the year 1453 and slaughtered the Christians in Constantinople.”

Theano and Mr. Plex are deep in thought as they try to determine the arrangement of 15 Turks and 15 Christians that permits the Christians to live but sets up the Turks for certain death.

You begin to draw on the column. “Here, let me give the answer. This diagram shows the arrangements of Christians and Turks. I’ve represented the circle of men by a line. The last Turk stands next to the first Christian in the circle.”

C C C C C T T T T C C T T C T C C T C T C T T C T T C C T T

X X X X X 12 5 7 3 X X 9 1 X 15 X X 11 X 14 X 6 4 X 8 2 X X 13 10

“If you start counting at the first man, you’ll see that the Turks will be counted out first, in the order indicated by the numbers. For example, the 1st Turk thrown over the ship is marked as a “1”. The 15 X’s are the Christians who survive.

Turks being thrown over the side of a ship.

Theano studies your diagram. “The last poor soul is marked 15,” she says. “He’ll see his screaming comrades all thrown overboard and probably never get the chance to realize the Christians orchestrated the whole thing.”

Mr. Plex pulls a notebook computer from beneath a huge deformed statue of Apollo and types feverishly. “Sir, it seems this puzzle can be solved purely mechanically. I can have 30 array elements in my program, mark my starting point, decimate by 13, and note which are the first 15 elements to be counted out.”

“Quite so.”

Far away, over the hills, among the camellias, you think you see someone moving. You hear steps echoing. But it’s only the rustling of leaves.

You turn back to Mr. Plex and Theano. “Here’s another decimation puzzle. Fiendishly difficult. Five mortals and five gods found five emeralds. They soon began to fight as to who should get the jewels. Zeus bellowed, ‘We’ll arrange ourselves in a circle, and count out individuals by a fixed interval, and give an emerald to an individual as he leaves the circle.’ Zeus was clever and arranged the circle so that by counting a certain mortal as ‘one’ he could count out all the gods first. The arrangement of gods and mortals was:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

M M M G G G M G G M

The count starts with the mortal at the extreme left, goes to the right, and then returns to the leftmost individual remaining. Each individual ‘counted out’ steps out of the circle and is not included in the count thereafter.”

You pause, and grin. “Plato was the mortal who was counted as one, and he insisted on his right to choose the interval of decimation. Again, the count starts with Plato, the mortal at the extreme left. Plato’s astute choice counted out all the mortals first. What interval will count out the five gods first, and what will count out the five mortals first?”

Theano and Mr. Plex study the problem. After several minutes, Theano lets out a whistle of surprise and gives you the two solutions.

“Mon Dieu!” screams Mr. Plex.

You take a quick breath of utter astonishment. “Theano, you’re a genius!” You run over and shake her hand.

Theano draws her lips into a tight smile. “Thank you.”

Before you have a chance to congratulate her further, you hear running sounds coming from the valley near the temple.

Theano puts her hands over her forehead to shield the sun. “Oh, no,” she yells as she points. “It’s my husband.”

You squint and see Pythagoras running toward you swinging his kithara like a club.

“Sir—”

“Not now Mr. Plex.”

“Sir, it’s the transfinites. They’re moving toward us.”

You turn and see Apollo shuffling about on the marble floor. His cloak of colorful flesh makes him look like undulating, psychedelic jellyroll.

“Oh no!” Mr. Plex screams. “Apollo is Pythagoras’ favorite god. What if he sees this?”

A few crustaceans, the keepers of time, begin to repair a crack in the floor beneath Apollo’s massive feet.

You grab Theano’s hand. “Quick, back to the storage closet.” You turn to Mr. Plex. “Stay here and scare Pythagoras away.”

“Sir, I can’t do that.”

Pythagoras’ dark watchful eyes miss nothing. “Theano!” he screams.

You gaze at Pythagoras’ huge kithara. He seems to be running toward you. “Mr. Plex, do something!”

“Yes, sir.”

Mr. Plex rises up on his hindlimbs and stretches himself like Hercules unchained between two Temple columns. The sunlight reflects off his diamond body as his abdomen pulsates and his diamond teeth sparkle. He tosses back his head and gives a lion-like roar.

THE HISTORY BEHIND THE SCIENCE FICTION

Turks and Christians

Theano was interested in why there was conflict between the Christians and the Turks. Moslems and Christians have had a long history of discord in the Near East, including the Crusades where European Christians came to the Holy Land in an attempt to take it away from the Moslems. Conflict lasted for centuries.

One famous example of strife between Turks and Christians occurred in the middle 1400s. In the year 1451, Mohammed II, surnamed the Conqueror, came to the Ottomon throne at the age of 21. In June 1452, he declared war on Constantinople and attacked with 140,000 men. His Moslem comrades were inspired by the belief that to die for Islam was to win paradise in the afterlife. Interestingly, Mohammed had hired Christian gunsmiths to create for him the largest cannon known to humanity: it hurled stone balls weighing 600 pounds.

Emperor Constantine, himself a Christian, led the defense of Constantinople with 7000 soldiers. His brave brethren had lances, small cannons, bows and arrows, torches, and crude firearms. Alas, his city walls were eventually destroyed. On May 29, the Turks fought across a moat filled with fellow Moslem soldiers and began to terrorize the city. Constantine himself was in the thick of the battle. When he finally was surrounded by the Turks, he screamed out, “Cannot there be found a Christian to cut off my head?” He continued to fight but disappeared and was never heard from again.

Once they had conquered Constantinople, the Turks massacred thousands of Christians. Nuns were raped. Christian masters and servants were taken as slaves. The St. Sophia church was transformed into a mosque and all its Christian insignia removed.

The fall of Constantinople and transfer of power from Christian to Islamic rule upset every throne in Europe. The wall between Europe and Asia had fallen. The papacy, which had always hoped to win over Greek Christianity, now saw the rapid conversion of millions of southeastern Europeans to Islam. Trade routes, traditionally controlled by the West, were now in “alien” hands.

All of this had a profound effect on mathematics. In fact, the fall of Constantinople to the Islamic Turks actually caused mathematics to flourish. The migration of Greek mathematicians to Italy and France was accelerated. Vasco de Gama and Columbus stretched the confines of civilization, and Copernicus stretched the heavens. Centuries of asceticism were forgotten in an explosion of art, math, and poetry, and pleasure. As Will Durant notes in his book The Reformation, the western migration of Greek scholars to Europe “fructified Italy with the salvage of ancient Greece.” Religious war altered the landscape of mathematics and science forever. And the modern world was born.

Although the decimation puzzle in this chapter may appear to be simple from a mathematical standpoint, these kinds of problems have been studied for centuries. Perhaps more notable is that these problems have been tied to religious quarrels. For example, the “Turks and Christians” puzzle is presented in various literature, although I do not know from where (and when) it ultimately originates.1