|

I can’t help thinking that scientists who write books about God and the Universe would be better advised to write more scientifically, and less poetically.

—Ralph Estling, The Skeptical Inquirer, 1993

I was astonished to discover how many of my close scientific colleagues practice a conventional religion.

—Paul Davies, The Mind of God |

From beneath Hercules’ thin, drooling mouth, a hundred throat appendages quiver aperiodically. The statue’s several feet resemble horseshoe crabs, and its toes look like slugs.

Theano motions to the storage room door. “Don’t go out there again,” she says, her face clouding. “Not ever. It’d be asking for trouble.”

You are sitting next to Theano on a straw mat on the floor of the temple’s storage room. “You’re right, it’s too dangerous. Pythagoras may believe Mr. Plex to be an evil god who deserves destruction, or perhaps Pythagoras is jealous of the time you are spending away …”

Mr. Plex’s right forelimb twitches uncontrollably. “Sir, thank goodness she’s finally knocked some sense into you. I–I scared Pythagoras away for the moment, but I’ve a feeling he’ll be coming back.” Mr. Plex sounds out of breath.

You nod. “Next time I’ll handle the situation myself. It wouldn’t be good to have them start a religion based on Mr. Plex’s peculiar physiognomy. In any case, there’s nothing to worry about if we stay in this closet and watch the view-screens.”

Theano gestures to the walls. “What’s with the five view-screens?”

“I’ve positioned electronic flies at the north, south, east, and west sides of the temple. Pythagoras won’t be able to return here without us seeing him approach.”

Theano rises and stalks to the corner of the room. You have never seen her behave in quite this manner. In a moment she reappears. “What good is us seeing Pythagoras approach? He’ll find us eventually.”

You shake your head. “We can protect ourselves if necessary.”

Mr. Plex looks at the view-screens. “Sir, why do you have five view-screens?”

“It’s an experiment, Mr. Plex. I’ve sent a fly through time to the 13th century.” You point to the fifth screen. “Today we’ll talk about the Ars Magna of Ramon Lull.”

“Excellent!” Mr. Plex screams.

Theano places her hands on her hips. “How can you have one of your teaching sessions at a time like this. Pythagoras could return any minute.”

“Dear, just—”

“I’m not your ‘dear.’ ”

Everyone is quiet. No one moves.

Mr. Plex ambles closer. “Ma’am, he meant no disrespect.”

You nod.

Theano sighs and kicks at a cheeseburger wrapper.

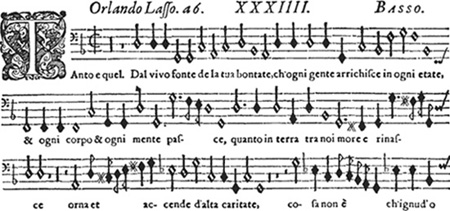

The nine steps leading to the Heavenly City by Ramon Lull. (From the Liver de ascensu.)

During your last few days together, Theano has become more proficient in English with all its idioms. At first you were merely fascinated by her, charmed by her. Then you felt an emotional connection that appeared to be growing deeper with each day. Now you are desperate to teach her all of the profundities of life, to make her share your passion for mathematics, to make her love your books, art, music—to know how to fend for herself in the 21st century without being harmed. Still Theano keeps just beyond your emotional reach. In the next few days, you hope that some of the distance between you and her will melt away.

You shake your head to clear your thoughts. “As I was about to say, our time-fly is circling Ramon Lull, a Spanish theologian born in the year 1234.”

Mr. Plex grins. “Four consecutive digits.”

You nod as a noisy image of a man with a long white beard appears on your screen. He stands on the top of a large saddle-shaped mountain and gazes up towards the heavens.

“Sir, what’s he looking at?”

You send a command to the electronic fly, and it points its head upward.

The sky is a perfect china blue, and great curling clouds race by like sentient sailing ships in a gust of wind. The fly returns its view to Ramon Lull.

“Sir, he doesn’t look too good.”

You nod. “The year is 1274. The place is Mount Randa on the island of Majorca. For several days he’s been fasting and meditating. According to historical records, he’ll soon experience a vision where God reveals secrets to confound infidels and prove the certainty of religious dogma. Our history books also tell us that Lull will have a vision of the leaves of a lentiscus bush becoming mysteriously covered with letters from different languages. These different languages are the ones in which Lull’s Great Art are destined to be taught. Soon after he has these visions, Lull will write the first book of many called the Ars Magna.” You say the words Ars Magna in a hushed voice. “The book describes how to use Lull’s mathematical methods for seeking the ultimate truth of the universe.”

Theano wanders closer and appears interested. Good. She cannot resist the lure of your lesson. Perhaps any anger she has felt will dissipate like fog in the warm sun.

“Sir, did Lull’s contemporaries see him as a genius or a lunatic?”

“Lull started his life with great hedonistic indulgence similar to St. Augustine, and he had a passion for married women. Nonetheless, Giordano Bruno, the great Renaissance martyr, considered Lull divine. Bruno thought Lull’s work contained a universal algebra by which all knowledge and metaphysical truths could be understood.”

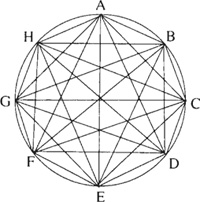

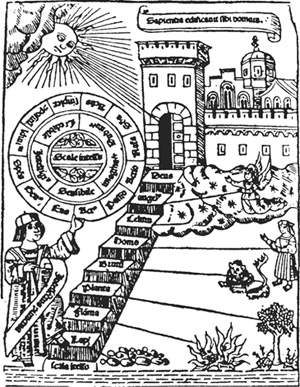

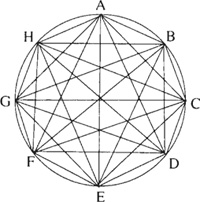

You begin to sketch on the temple wall. “Lull believed that in every branch of knowledge there are a small number of simple basic principles, and by exhausting all possible combinations of these principles, we can explore all knowledge. To help Lull arrange and study all possible combinations of words, phrases, or ideas, he designed various geometrical figures and wheels. For example, we can arrange a set of words in a circle and connect one to another with lines.”

“Lull’s most famous word organizer consisted of concentric circles which rotated about a central axis. The letter A representing God was often placed at the center of the circle. Around the circles were divine attributes such as goodness, greatness, eternity, and so on. By connecting the various attributes, we can obtain various permutations of concepts that stimulate the mind. For example, we can meditate on the composite idea that God is infinitely just. Lull even wrote a book describing how preachers could use his concentric wheels to arrive at stimulating topics for sermons.”

Theano begins to scribble various diagrams on the wall. She grins. “Sir,” she says imitating Mr. Plex’s twangy metallic voice, “how could this help him learn anything about the universe?”

You smile. “Lull believed that each branch of knowledge rested on a few principles that formed the structure of knowledge in the same way that geometrical theorems are formed from basic axioms. By using his wheels to produce all combinations of principles, one explores all possible structures of truth and obtains universal knowledge.”

Mr. Plex comes closer. “Seems fairly useless.”

“Not entirely. The Lullian principle of randomly combining words to stimulate the mind is useful in producing startling fictional plots and verbal imagery that might not be considered otherwise. Meditating on bizarre combinations leads your mind to offbeat paths. In the 20th century, someone even once marketed a device to fiction writers called a “Plot Genii.” Using this device, a hopeful author turns concentric circles to produce different combinations of plot elements.”

You turn toward Mr. Plex. “Care to do a little experimenting on the computer?”

Mr. Plex nods. Theano’s left eyebrow raises.

“You can create your own Lullian computer poetry generator by randomly selecting words and phrases which are then placed in a specific format, or ‘semantic schema.’ The program starts by reading 30 different words in five different lists (or categories), and stores these words in the program’s memory arrays. The five categories are: adjectives, nouns, verbs, prepositional phrases, and adverbs. The words are chosen at random and placed in Ramon Lullthe following semantic schema, or minor variations of this schema:

Poem Title: A (adjective) (noun 1)

A (adjective) (noun 1) (verb) (prepositional phase) the (adjective) (noun 2).

(Adverb), the (noun 1) (verb).

The (noun 2) (verb) (prep) a (adjective) (noun 3).

The fact that “noun 1” and “noun 2” are used twice within the same poem produces a greater correlation—a cognitive harmony—giving the poem more meaning and solidity.”

“Sir, let me make a list of words, and write a computer program.”

Theano tosses Mr. Plex a personal computer, but her aim is significantly worse than yours, forcing Mr. Plex to make a leaping dive for the computer. He catches it but, in doing so, crashes into a marble frieze of representations of harpys, centaurs, Albert Einstein seizing Hercules, and of men feasting running about the entablature. Both Einstein and Hercules crash down upon Mr. Plex.

Mr. Plex struggles to free himself of them. “Did the transfinites warp Aphrodite into Einstein?” He shakes his head. “Never mind.” Mr. Plex then furiously types on the computer’s keyboard with his multiple legs.

The computer program asks for a number to seed a random number generator, and also for the number of poems to be generated:

>Please enter a seed for the random number generator > 81557

>How many poems would you like? > 5

When Mr. Plex presses the computer’s Enter key, the computer prints five poems. He hands you a computer printout:

A CHOCOLATE PROPHET

A chocolate prophet drools while painting the glistening avocado.

Sensuously, the prophet gyrates.

The avocado chatters near a crystalline jello pudding.

A SEXY DREAMER

A sexy dreamer flies while eating the moldy spine.

While gradually melting, the dreamer squats.

The spine squats deep within a vibrating ocean.

A SKELETAL LIMB

A skeletal limb sings while dismembering the golden unicorn.

Vigorously, the limb smiles.

The unicorn screams above a lunar brain.

A CRYSTALLINE INTESTINE

A crystalline intestine regurgitates while listening to the moist dream.

Hideously, the intestine collapses.

The dream evaporates while grabbing at an apocalyptic sunset.

A BURNING MOUNTAIN

A burning mountain withers while dreaming about the glistening prophet.

With great deliberation the mountain makes love.

The prophet laughs while grabbing at a glittering snail.

“Sir, these poems don’t impress me.” He pauses. “But they sound more sophisticated than a simple random number generator could produce. All I did was give it thirty different words for each category.”

There is an odd mingling of wariness and amusement in Theano’s eyes. “Here let me try that,” Theano says. She types in a different number for the random number generator.

> Please enter a seed for the random number generator > 90210

> How many poems would you like? > 10

She presses the computer’s Enter key, the computer prints ten poems, and she hands you a computer printout:

A MAGNETIC BONE

A magnetic bone thrusts while puffing the frost-encrusted jello pudding.

While feeding, the bone wanders.

The jello pudding chatters while grabbing at a moldy knuckle.

A HALF-DEAD TOWER

A half-dead tower phosphoresces close to the delicious tongue.

While feeding, the tower smiles.

The tongue shakes at the end of a moldy robot.

A DYING TORCH

A dying torch chews inside the happy avocado.

Blindly the torch screams.

The avocado gyrates in synchrony with a moist centipede.

A CHOCOLATE VACUUM TUBE

A chocolate vacuum tube oscillates while massaging the frost-encrusted goose.

Grotesquely, the vacuum tube makes love.

The goose oozes simultaneously with a percolating sunset.

A CRYSTALLINE EARTHWORM

A crystalline earthworm jumps inches away from the sleep-inducing knuckle.

Hideously, the earthworm buzzes.

The knuckle regurgitates below a hungry web.

A FRIGID SUNSET

A frigid sunset cries before the dying intestine.

With all its strength, the sunset sings.

The intestine wanders while grabbing at a moldy goose.

A GOLDEN SAPPHIRE

A golden sapphire evaporates close to the moist mountain.

With great deliberation, the sapphire chatters.

The mountain gasps near a moldy brain.

A FAIRYLIKE FLAME

A fairylike flame sings inches away from the dying avocado.

While waving its tentacles, the flame undulates.

The avocado trembles while sterilizing a shivering tongue.

A DYING AVOCADO

A dying avocado regurgitates beneath the vibrating cloud.

Before dying, the avocado regurgitates.

The cloud drools a million miles away from a black sunset

A PIOUS MAGICIAN

A pious magician implodes while rubbing the green veil.

Happily the veil shines.

The magician sings in synchrony with a skeletal diamond.

You study the poems. “Mr. Plex, your choice of words for your word lists is a bit odd.”

“That’s an understatement,” Theano interjects.

“But you now see the Lullian concept in action. Even with a random choice of words, the computer creates simple poems. With a little more sophistication of rules, the poems might be quite thought-provoking.” You reach for the computer. “Here, hand me that. I have my own word lists to try. The words come from Edward Fitzgerald’s translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam.”

You type in the new word list and have the program print 10 new poems:

AN UNBORN SPANGLE OF EXISTENCE

An unborn spangle of existence ascends toward heaven and hell.

While transmuting, the spangle of existence jumps.

Heaven and hell weep while seeking their external destiny.

A BURIED IDOL

A buried idol evolves inside the divine nightingale.

In mind-inflaming ecstasy, the idol burns.

The nightingale dreams within annihilation’s waste.

A CONSCIOUS CLAY

A conscious clay phosphoresces while pulling apart its shivering destiny.

Gazing longingly into space, the clay regurgitates.

Destiny evolves at the tip of heaven and hell.

AN UNBORN HYACINTH

An unborn hyacinth thrusts before the everlasting penalties.

With great satisfaction, the hyacinth sings.

The everlasting penalties evolve while listening to a shivering vessel.

A FROST-ENCRUSTED BIRD OF TIME

A frost-encrusted bird of time breathes at the end of a loaf of bread.

Hesitantly, the bird of time gyrates.

The bread cries while staring at a skeptical lamp.

A SKELETAL MORNING OF CREATION

A skeletal morning of creation oozes on the unborn seventh gate.

With great speed, the morning of creation laughs.

The seventh gate disintegrates while dreaming about a phantom annihilation.

A DYING PARADISE

A dying paradise vanishes at the end of the praying angel.

Gazing longingly into space, paradise burns.

The angel shivers while pulling apart a hungry loaf of bread.

TRANSLUCENT PROPHETS

A translucent prophet dreams within the shining blossom.

Ever-so-slowly, the prophet undulates.

The blossom wanders in spite of a shining key.

AN ETERNAL RUBY

An eternal ruby dissolves besides the invisible Sultan.

Erotically, the ruby makes love.

The Sultan regurgitates near a glowing throne.

AN INFINITE SWORD

An infinite sword gasps while rejecting the divine revelation.

While shivering, the sword evolves.

The revelation sighs while touching an unborn universe.

“Interesting,” Mr. Plex says.

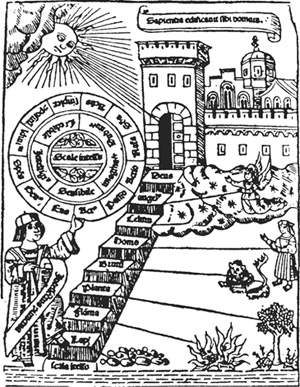

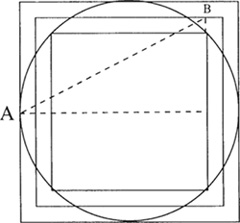

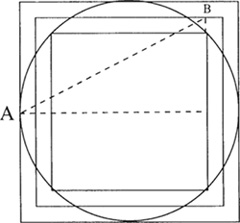

You nod. “Let me tell you about the mathematical side of Lull. He was a mathematician of sorts, although not a very good one.” You go over to a wall and begin to draw. “Here’s my favorite Lullian diagram.” You point to a rectangle filled with words and geometrical shapes (see below). “Lull used this figure to show how the mind can conceive of geometrical truths not apparent to the senses, and to prove that there is only one universe rather than many universes.” You pause. “The diagram at the middle of the bottom is of greatest interest. I’ll redraw it more neatly.” (see p. 111). Theano and Mr. Plex lean closer.

Diagrams used by Renaissance Lullists.

“To produce the figure, we first inscribe and circumscribe a square about a circle. Next draw a third square, called the Lullian square, midway between the other two squares. By midway, I mean that the distance of the top of the outer square to the top of the midway square is equal to the distance from the top of the midway square to the top of the inner square. What can we know about the area and perimeter of this third square?” You pause. “Ramon Lull asserted that the third square has a perimeter equal to the circumference of the circle as well as an area equal to the circle’s area.”

Theano’s fine, silky eyebrows rise a trifle.

Mr. Plex is gesturing wildly to the view-screen, but you pay no attention, wishing to finish your thought.

“Today, we know this is not true, that Ramon Lullwas wrong about the areas and perimeters. However, isthere anything we can say about the area and perimeterof this third square in relation to the circle?”

“Sir, look at the view-screen.”

You turn and see a cloud of dust appearing on your right screen.

“I can’t quite see what it is.”

“Mon Dieu!” Mr. Plex screams.

On the view-screen are ten Greek warriors coming toward the temple. They are clad in magnificent garments of war—golden, studded harnesses and bronze helmets. At their sides dangle their traditional weapon of war, the long sword. They ride massive, black stallions. From their mounts hang daggers, sabers, rapiers, scimitars, wide-blade knives called misericords, and various other instruments of mayhem, the function of which you cannot quite discern.

Enlargement of bottom, middle of figure on page 110.

They ride in perfect formation, each rider located at a point in four rows forming the tetraktys.

“Let me handle this,” you say.

Theano pulls on your arm. “You promised me you wouldn’t go out there.”

“Theano, I’m sorry. This will take a minute.”

You open the backroom door and Theano follows. Mr. Plex remains behind, his forelimbs and abdomen shaking like an untuned engine.

“Maybe they’re Pythagoreans,” Theano whispers.

“Maybe Pythagoras hired them?”

“What do we do now?” Theano asked. Her whole body tightens, and then she takes a breath.

“Let’s wait and see what happens.” You feel a creeping uneasiness at the bottom of your heart.

When the riders are in earshot, you adapt your speech and body language to their inflated style and manner.

“From whence come these noble warriors?!” you cry. You try not to show any fear.

Theano stared up at the riders. Waiting. Tense. “What in hell are you talking about?” she whispers as she kicks you in the shin.

“Play along with me.”

The large warriors remove their helmets and dismount. Five of the riders break from the tetraktys formation and gallop away into the distance. Could it be that they wish to report your location to Pythagoras? Or do they simply feel that five soldiers are sufficient to deal with you and Theano?

The tallest rider comes closer.

Standing before you is a huge muscular man with a dark beard. His eyes almost seem to glow a fierce red as he shouts something that is probably a variant of ancient Greek.

“Can you understand him?” Theano says.

“Sort of. I studied Greek dialects while on my museum ship in the future.”

The warrior’s grey-green eyelids droop and ooze a tiny amount of liquid which smells like absinthe, “πoιυη?(What dost thou want in Our Kingdom?)” he says in a voice several octaves too low.

You attempt to mimic his ostentatious manner of speech. “I seek wise Pythagoras, geometer extraordinaire, possessor of all knowledge.”

“Then you will seek him forever, Warrior. Leave whilst thou are able!” He threatens you and Theano with his long sword. The voice of the warrior is eerie, like a low-pitched wind whistling through a window on a lonely January night.

“And what of the pre-pubescent tart?” taunts another warrior as he lasciviously leers at Theano. You clench your fists so that your fingernails dig painfully into your palms.

Suddenly the two warriors remove a peculiar looking weapon from their cloaks and knock you into a lentiscus bush.

Since you generally avoid bringing advanced weapons back in time, the long sword is your weapon of choice in ancient Greece. This is not too much of a liability since gunpowder doesn’t yet exist. In one way this restriction is a welcome one for you. You are an expert using both the English cutlass and the French cup hilt rapier. To Greece you have brought a beautiful replica of a 17th century English cutlass with a quillon to protect your hand. You fashioned the blade yourself using bundles of iron strips, hammered together, which you cut and bent repeatedly. Subsequent carbonization of the metal improved its strength and temper.

You disentangle yourself from the lentiscus bush and shout back in their archaic style of speech. “Thou darest challenge me?” It is time to bring out the heavy artillery. You reach into a thin chamber you have previously hollowed out in a column of the Temple.

Whenever you’re threatened, you seem to go haywire and lose control. For some reason, you aren’t afraid. Perhaps it is your martial arts training. Perhaps you are a little bit crazy.

One of the warriors kicks you in the knee, and the warrior blood within you rises to fever pitch. Your hand yearns for the touch of your sword, yearns for the glory of battle. You hold your sword above your head.

“τ τρακτοζ!” you scream to assuage your humiliation. You grin and then lunge with the fury of a rabid wolf.

τρακτοζ!” you scream to assuage your humiliation. You grin and then lunge with the fury of a rabid wolf.

“Theano, stay behind me,” you shout.

You lunge at all five of the warriors, your ever-moving blade producing a wall of flashing, cutting steel through which no warrior dares transgress. One warrior comes a little too close, and you stab him in the chest. Another throws his sword at you. You dodge it and then stab him in his arm. You grow weak, but you fight on. You’ve always loved a good fight.

The third warrior stares at you but does not move. It appears that he is assessing your fighting skills. He snarls something which roughly translates to “pretty damn good.” Then he runs toward you. Your sword slashes, thrusts, and parries his every attack. He is about to bring his sword onto your head when you slip under him and smash your fist into his groin. A second later, you run your sword through his neck.

“Watch out!” Theano cries. She points to the leader who wields a double-bladed sword shaped like the Greek letter π. You have heard stories about these terrible instruments of mutilation and death. Ordinarily, when one sword hits another sword the vibration spreads out to affect the entire sword. With π swords, some vibrational modes are trapped within a branch of the π shape, and thus the double-blade damps vibrations, making the sword quiet and sturdy. When the warrior strikes your sword you hear no loud metallic ringing sound. Just silence. It is unnerving. The warrior notices your consternation and smiles. With lightning speed, you smash his body with your arm while at the same time throwing a piece of lentiscus bush at his head. He stops smiling.

“Arrrrrr!” screams the warrior. His long nose is pinched and white with rage. You scream back at him with a furious voice. Then you run toward him. At last, with one ruthless disengagement and thrust, you kill the leader of the five warriors.

You look at the one remaining warrior. “I don’t know who is uglier, you or Medusa.” You laugh at your own joke with a judicious amount of false gusto.

The warrior roars and attacks you. His strength is so great that the strike of his sword splits your sword into two useless pieces. You fall to the ground. If only you had your other sword hidden back in the storage room. You reach for the puny dagger in your belt. The warrior catches hold of your wrist, his rough fingers forming a muscular bracelet of incredible strength. You hear Theano gasp and see her run to the warrior. Then she gives a swift, vicious kick to the warrior’s hip. The warrior loosens his grip.

You are about to take a deep breath of relief when the warrior’s sword rips into you. The pain is so devastating that you drop the dagger, feeling pain like nothing you have ever known. You think of Theano, your growing affection for her, and you tell yourself you have to try to protect her, and that you aren’t going to die, aren’t going to die.…

The huge warrior comes at you again with his long sword. Without warning, you launch your foot up at his throat with a powerful karate kick. He is stunned and drops his sword. With a quick intake of breath like someone about to plunge into Arctic air, you quickly grab his sword, lunge forward, and remove his head.

THE SCIENCE BEHIND THE SCIENCE-FICTION

The Life of Ramon Lull

The character of Ramon Lull (1234–1315) is, of course, real. In fact, in his Book of Contemplation, Lull seeks to prove all the major tenets of Christianity. In this book, he is preoccupied by number symbolisms. For example, the work is divided into five books to symbolize the five wounds of Christ. Forty subdivisions symbolized the 40 days Christ spent in the wilderness. One of the 366 chapters is to be read each day, and the last chapter read only in leap years. Each chapter has ten paragraphs (the ten commandments), and each paragraph has three parts (the trinity), making a total of 30 parts per chapter (the 30 pieces of silver). Geometrical objects, such as circles, are often introduced as metaphors.

Lull often used letters to stand for words and phrases so as to condense his arguments into an algebraic form. For example, here is part of a paragraph from Chapter 335:

Since diversity is shown in the demonstration that the D makes of the E and the F and the G with the I and the K, therefore the H has certain scientific knowledge of Thy holy and glorious Trinity.

Martin Gardner, who has written extensively on Ramon Lull’s work, notes of the Ars Magna:

There are unmistakable hints of paranoid self-esteem with the value Lull places on his own work in the book’s final chapter. It will not only prove to infidels that Christianity is the one true faith, he assures the reader that he has “neither place nor time sufficient to recount all the ways wherein this book is good and great.”

As you mentioned to Theano and Mr. Plex, Lull used many concentric wheels to examine universal truths. For example, one of Lull’s wheels is concerned with: God, angels, heaven, man, the imagination, the sensitive, the negative, the elementary, and the instrumental. Another is used to ask questions such as: what? why? how great? when? where? how? etc. In his books Ascent and Descent of the Intellect and Sentences, he uses the rotating circles to formulate questions such as:

1 Where does the flame go when a candle is put out?

2 Why does the rue herb enhance vision while onions weaken vision?

3 Where does the cold go when a stone is warmed?

4 Could Adam and Eve have cohabited before they ate their first food?

5 If a child is slain in the womb of a martyred mother, will it be saved by a baptism of blood?

6 How do angels communicate with one another?

7 Can God make matter without form?

8 Can God damn Peter and save Judas?

9 Can a fallen angel repent?

In his book, Tree of Science, Lull asks over 4000 similar questions! Sometimes Lull gives answers to the questions, while other times he simply poses the question and lets the reader formulate a response.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Below is a list of questions I frequently receive regarding Ramon Lull, followed by my brief answers.

1 Did Lull have other outlets for his creative output? Yes. Lull was a poet, and his collection of poems on The Hundred Names of God is one of his best known works.

2 Did Lull believe one could communicate with the dead? Yes. He rejected geo-mancy (divination using signs derived from the earth) but accepted necromancy (the art of communicating with the dead). Lull even used the success of necromancers as a proof of God’s existence.

3 Did Lull belong to a specific religious order? Yes. While in a Dominican church he saw a brilliant star and heard a voice speaking from above: “Within this order thou shalt be saved.” Unfortunately, the Dominicans had little interest in his art, and Lull therefore joined the Franciscans who found it of some value.

4 How did Lull die? At the age of 83, Lull set sail for the northern coast of Africa. By this time he had a long white beard. In the streets of Bugia, he started to shout about the errors of the Moslem faith and was stoned by an angry mob. Before he died, Lull is said to have had a vision of the discovery of the American continent by a merchant. Lull’s remains now rest in the chapel of the Church of San Francisco at Palma, Spain, where they are revered as those of a saint.

5 Does anyone follow Lull today? Yes. Interest continues in Lull and his work. For example, the Second International Lullist Congress took place at El Encinar and Miramar, Majorca, in 1976, bringing together famous Lullist scholars from around the world.

The Lullian Square

Before you were interrupted by the Greek warriors, you started to tell Theano and Mr. Plex about a figure where a square is inscribed and circumscribed about a circle (p. 111). As mentioned, Lull claimed that a third square positioned midway between the two original squares has a perimeter equal to the circumference of the circle as well as an area equal to the circle’s area.

Could Lull have been correct?

If we let R be the radius of the circle, then the outer square has sides of length 2R and an area of 8R2. The inner square has sides of length  R and an area of 2 × R2. The square in the middle has a side which is the average of the inner and outer square and therefore has a side length of (2 +

R and an area of 2 × R2. The square in the middle has a side which is the average of the inner and outer square and therefore has a side length of (2 +  ) R/2, and an area of (3 + 2

) R/2, and an area of (3 + 2 )R2/2 and perimeter of (4 + 2

)R2/2 and perimeter of (4 + 2 )R.

)R.

We can compare the area and perimeter of the Lullian square with the circle by assuming R= 1:

|

Circle |

Lullian Square |

Area |

3.14 |

2.91 |

Perimeter |

6.28 |

6.82 |

A circle encompasses more area than any other shape of equal perimeter length. In other words, you would need less fence to enclose a circular piece of land than a square piece of land.

Jeff Vermette from Rockville, Maryland, points out that any geometric figure that has both the same perimeter and area of a given circle must be a circle itself. Therefore, the Lullian square could not have had the same area and circumference as the circle. The ratio between the area and the perimeter is maximized when the figure is a circle, so any figure whose ratio equals the ratio for a circle must itself be a circle. This elegantly shows the invalidity of Lullian mathematics without having to resort to calculators and three significant digits to demonstrate the fallacy.

Martin Gardner, in Science: Good, Bad and Bogus, notes that if a diagonal line AB is drawn on Lull’s figure, as shown on page 111, it gives an amazingly close approximation to the side of a square with an area equal to the area of the circle. Why is this so?

Computer Poetry

In this chapter, we’ve also discussed the Lullian approach to generating computer poetry, a subject I cover in my book Computers and the Imagination. Experiments with the computer generation of poetry, Japanese haiku, and short stories provide a creative programming exercise for both beginning and advanced students. Computer-created poetry and text also provides a fascinating avenue for researchers interested in artificial intelligence—researchers who wish to “teach” the computer about beauty and meaning. You may want to read about early work in the computer generation of poetry in Riechardt’s book, Cybernetic Serendipity. Other past work includes the book The Policeman’s Beard is Half Constructed—the first book ever written entirely by a computer. The program which generated the book was called RACTER and was written by W. Chamberlain and T. Etter.1 Finally, there is the Kurzweil Cybernetic Poet, a computer poetry program which uses human-written poems as input to enable it to create new poems with word-sequence models based on the poems it has just read. When these computer poems are placed side by side with human poems, many humans can not judge which poems were made by humans and which by the Cybernetic Poet.

You will also find that computer-produced texts are a marvelous stimulus for the imagination when you are writing your own (non-computer generated) fictional stories and are searching for new ideas, images, and moods. If you are a visual artist in search of new subject matter, computer-generated poems can provide a vast reservoir of stimulating images.

If your computer has access to a thesaurus, you may induce further artificial meaning in your computer-generated poems. This is accomplished by using the thesaurus to force additional correlations and constraints on the chosen words. For example noun 1, noun 2, and noun 3 in the semantic schema would all appear within the same thesaurus entry. You should also design your own semantic schema and use additional word lists. Try using probability matrices to produce the poetry. The matrices would consist of an array which makes your program more likely to pick certain combinations of words. Some entries in the matrix may be zero, which would disallow impossible combinations of words.

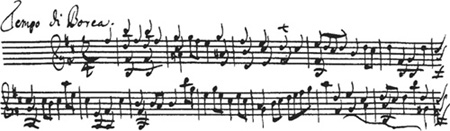

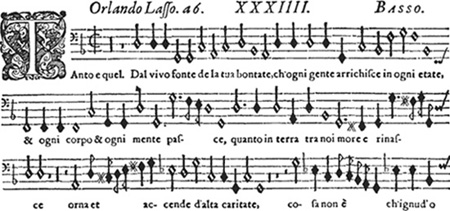

Lullian Approach to Music Generation

You may occasionally encounter natural scenes that remind you of a painting, or episodes in life that make you think of a novel or a play. You will never come on anything in nature that sounds like a symphony.

—Martin Gardner, On the Wild Side, 1992

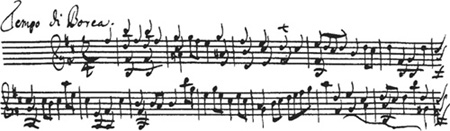

In my book Mazes for the Mind: Computers and the Unexpected, I discuss Lullian methods for generating melodies. In particular, I describe the fictional work of Professor Muteer of the Electrical Engineering Department at Harvard University who decided to build a musical melody generator that would continuously produce different 50-note melodic progressions. The melody machine would generate one melody after another, selecting for each melody a different combination of notes from the piano keyboard. His machine consisted of 88 oscillators, each of which produced a single tone. A random number generator was used to select which of the 88 oscillators were playing at any particular moment. The machine played the 50 random notes, one at a time.

Other versions of his music machine generated all possible 50-note melodies by sequentially trying all 88 tones for the first oscillator, while keeping all the others constant, and then stepping each oscillator sequentially (something like an odometer on your car’s dashboard). Here are the first few melodies this version of the machine produced for Professor Muteer, starting with A, B, C, D, …:

A, B, C, D, E, F, G, |

… |

(First Melody) |

B, B, C, D, E, F, G, |

… |

(Second Melody) The Ars |

C, B, C, D, E, F, G, |

… |

(Third Melody) Magna of |

D, B, C, D, E, F, G, |

… |

(Fourth Melody Ramon Lull |

… |

|

(Etc.) |

Notice that first the machine stepped through all possible notes for the first position in the melody, starting with the lowest note on the piano (A = 27.5 hertz). The first song that the machine produced using this approach (top line in the example) was simply a melody consisting of the first 50 white notes on a piano keyboard played in order from low to high pitch. In the second melody, the first A note has switched to B, and so on. Later in Mutcer’s research, black notes were also included. Either of these versions of the music machine (i.e., random or “odometer” versions), could be built without much difficulty. The duration of each note (quarter note, half note, eighth note, etc.) could also be selected at random.

Professor Muteer set the machine in action and began to listen to the endless sequence of different melodies that came from the music machine. Most of the melodies made no sense at all to his Western ear. They looked like this:

But since the music machine played all possible combinations of musical notes, Muteer began to find some nice tunes among the senseless, junk melodies:

Muteer reasoned that a careful search would also reveal every melody written by Michael Jackson, Madonna, Sheryl Crow, Yanni, Beethoven, Bach, the Beatles, and Bananarama. The machine would also produce every melody that Madonna discarded in frustration in her plush and high-tech recording studios.

Mutcer’s music machine would even generate every melody ever played since ancient humans blew on wooden flutes or on the horns of goats. Moreover the machine would play every popular tune in the future, every musical hit from the year 2200. Musical publishers having Mutcer’s machine would simply have to sit and listen, and select the good songs from the gibberish—which they do daily anyway.

A day after he built the music machine, Professor Muteer proudly showed the device to several of his graduate students. A week later, he instructed his students to plug themselves into the music machine every day and press a button to record a musical score whenever they heard a particularly interesting melody. A few machines were built, and students took turns listening. No machine was ever idle for more than a few seconds as one student replaced another at this listening task. Interestingly, after about an hour of listening, one student was rumored to hear several phrases from the beautiful Moonlight Sonata. After two weeks, Muteer himself heard both the Cantata No. 96 Aria Ach, ziehe die Seele mit Seilen der Liebe by Bach and Havah Nagilah (Israeli Hora). Another Student fainted when she heard a particularly powerful and hypnotic tune. Although she did not know it, the tune just happened to be a current best seller on a small red planet circling the star Alpha Centuri. Muteer copyrighted the best of the new musical scores, which were soon bought by large music publishers in New York and Rio de Janeiro. Muteer became a millionaire.

Lullian Generation of Book Titles

Book authors have used the Lullian approach to generate effective and marketable book titles. Nancy Kress, a Contributing Editor for Writer’s Digest, suggests that authors create marketable titles for their own books by first jotting down all the significant words in their story or novel. These can be words that suggest the action (love, murder, death), the characters (Sophie, Lazarus, salesman, husband), their relationships (lovers, strangers, enemies), the setting in time or space (IBM, the Four Season’s Restaurant, Summer, 1984), the theme (love, revenge), a motif (roses, vampires, cars, darkness), etc. Next, the words are arranged according to certain semantic schema. Here are some examples. (I would be interested in hearing from those of you who have found other best-selling titles using this approach.)

1 Possessive-Noun. Examples: Rosemary’s Baby (Ira Levin), Finnegan’s Wake (James Joyce), Sophie’s Choice (William Styron), Childhood’s End (Arthur C. Clarke), Schindler’s List (Thomas Keneally).

2 (Article)-Adjective-Noun. Examples: Jurassic Park (Michael Crichton), Spider Legs (Piers Anthony and Clifford A. Pickover), The Witching Hour (Anne Rice).

3 (Article)-Adjective-Adjective Noun. Example: Another Marvelous Thing (Laurie Colwin).

4 Noun-and-Noun. Examples: Pride and Prejudice (Jane Austen), Crime and Punishment (Doestyevsky), War and Peace (Tolstoy), Beggars and Choosers (Nancy Kress).

5 (Article)-Noun-of-Noun. Example: Death of a Salesman (Arthur Miller)

6 (ArticIe)-Noun-for-Noun. Examples: “Flowers for Algernon” (Daniel Keys), Requiem for a Heavyweight (Rod Serling).

7 Prepositional Phrase. Examples: Out of Africa (Isak Dinesen),/n Our Time, For Magna of Whom the Bell Tolls (Ernest Hemingway), Of Mice and Men (John Steinbeck). Ramon Lull

8 Article-Noun-Prepositional Phrase. Examples: Catcher in the Rye (J. D. Salinger), The Bridges of Madison County (Robert James Waller).

9 Infinitive Phrase. Examples: To Kill a Mocking Bird (Harper Lee), To Dance With the White Dog (Terry Kay).

10 Adverbial Phrase. Examples: Where the Wild Things Are (Maurice Sendak), How to Win Friends and Influence People (Dale Carnegie).

11 The Noun Who. Examples: The Spy Who Loved Me, The Man Who Melted (Jack Dann).

12 A Command. Examples: Remember Me (Mary Higgens Clark).

13 A Sentence with a Key Story Idea. Examples: “Can You Feel Anything When I Do This?” (Robert Sheckley), “I Have No Mouth But I Must Scream” (Harlan Ellison), “Repent Harlequin, Said the Ticktockman” (Harlan Ellison).

Although Nancy Kress suggests using this Lullian approach without the aid of the computer, I recommend that you write computer programs which dump lists of hundreds of titles in the same way that I have written programs to generate simple computer poetry. Scan through the list of computer-generated titles, pick the best, and go sell your novel!

Lullian Approach to Inventions

Where there is an open mind, there will always be a frontier.

—Charles F. Kettering

Those of you who are interested in computers or are creative engineers may like to use the Lullian approach for inventing new products and patenting the results. One way to stimulate your imagination is to have a computer program generate an invention title by randomly choosing from a list of devices and then also choosing from a list of features (Pickover, 1994). If you can think of suitable applications for the invention, it is relatively easy to embellish the basic concept suggested by the random title and generate patentable ideas using this approach. The list in Table 9.1 will help you understand this approach. Pick a device from the first column, add the word “with,” and then choose a feature from the second column. For example, “Mouse with Infrared Security Alarm” might be the title of your invention. Think about all the ways this could be achieved and all the applications of the device. Have your friends add devices and features to your own list for more interesting patent ideas.

The Pi Sword

The π sword, carried by the Greek warrior, has loose underpinnings in physics which suggest that strangely shaped objects can damp sounds when struck, and can be particularly strong. For example, consider hypothetical swords with fractal edges such as those seen in jagged Koch snowflake curves (Pickover, 1995). These kinds of swords may have unusual physical properties. In 1991, Bernard Sapoval and his colleagues at the Ecole Polytechnique in Paris found that fractally shaped drum heads are very quiet when struck. Instead of being round like an ordinary drum head, these heads resemble a jagged snow-flake. Sapoval cut his fractal shape out of a piece of metal and stretched a thin membrane over it to make a drum. When a drummer bangs on an ordinary drum, the vibration spreads out to affect the entire drum head. With fractal drums, some vibrational modes are trapped within a branch of the fractal pattern. Faye Flam in the December 13, 1991, issue of Science (vol. 254, p. 1593) notes: “If fractals are better than other shapes at damping vibrations, as Sapoval’s results suggest, they might also be more robust. And that special sturdiness could explain why in nature, the rule is survival of the fractal.” Fractal shapes often occur in violent situations where powerful, turbulent forces need to be damped: the surf-pounded coastline, the blood vessels of the heart (a very violent pump), and the wind-and rain-buffeted mountain.

|

Table 9.1. The Lullian Approach for Creating Patentable Inventions. Pick a Device from the First Column, add the Word “with,” and Then Choose a Feature from the Second Column. |

|

|

Device |

Feature |

|

|

Pen |

LED Flasher |

|

|

Clock |

Bell |

|

|

Key |

Speech Synthesis |

|

|

Mouse |

Light Meter |

|

|

Keyboard |

Touch-Activated Switch |

|

|

Joystick |

Timer Plus Relay |

|

|

Graphics Puck |

Missing Pulse Detector |

|

|

Trackball |

Voltage-Controlled Oscillator |

|

|

Terminal Screen |

Frequency Meter |

|

|

Pencil |

Light Meter |

|

|

Terminal Keys |

Infrared Security Alarm |

|

|

On/Off Switch |

Analog Lightwave Transmitter |

|

|

Dial |

Protection Circuit |

|

|

Remote Control |

Adjustable Siren |

|

|

Compass |

LED Regulator |

|

|

Level |

Wrist Band Attachment |

|

|

Screwdriver |

LED Transmitter/Receiver |

|

|

Watch |

Speech Recognition |

|

|

Cursor |

Volume Control |

|

|

Menu Icon |

1-Minute Timer |

|

|

|

Dual LED Flasher |

|

|

|

Neon Lamp Flasher |

|

|

|

Solar Cells |

|

|

|

Dark-Activated LED Flasher |

|

|

|

Break-Beam Detection System |

|

|

|

Phone Activated |

|

|

|

Phone-Controlled |

|

|

|

Piezioelectric Buzzer |

|

|

|

Bargraph Voltmeter |

|

τρακτοζ!” you scream to assuage your humiliation. You grin and then lunge with the fury of a rabid wolf.

τρακτοζ!” you scream to assuage your humiliation. You grin and then lunge with the fury of a rabid wolf. R and an area of 2 × R2. The square in the middle has a side which is the average of the inner and outer square and therefore has a side length of (2 +

R and an area of 2 × R2. The square in the middle has a side which is the average of the inner and outer square and therefore has a side length of (2 +