Ancient civilizations built the foundations of modern science [and math] on the study of cyclic events, usually astronomical ones. Sunrise and sunset, tides, the phases of the Moon, the annual march of the seasons, even the 18-year re-petition in the pattern of solar eclipses, were recognized more than 2000 years ago.

—Paul R. Weissman, Sky & Telescope, 1990

When the Cimetière des Innocens at Paris was removed in 1786—1787, great masses of adi-pocere’ were found where the coffins containing the dead bodies had been placed very closely together.

—Adipocere, Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed.

On the broad Downs, under the gray sky, nothing but Stonehenge, and all round, wild thyme, daisy, meadowsweet, and the carpeting grass.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson |

|

“Sir, where are we?”

Mr. Plex is stepping in a bed of stonecrop: showy flowers of white, yellow, pink, and red. A vine of pink orphine with blue-green leaves trails along his abdomen.

“Help me up,” Theano says, extending you her arm.

Slowly rising, you stretch your sore legs, and pull her up.

Theano takes a deep breath, smiles, and slowly turns to take in her surroundings.

The three of you are standing in the center of a circular structure of large upright stones.

You smile back at her as you run your hand through her long brown hair. “Enjoy the new setting?”

“You behave,” she says wickedly.

Mr. Plex sneezes. Perhaps it is the rich scent of honeysuckle.

“Sir, what month is it?”

“December.”

“Then why are flowers blooming?”

“Not sure. Maybe the transfinites are playing with us?”

Mr. Plex removes a flower from his abdomen. “Or maybe our presence in ancient Greece has altered the fabric of time. You know, the butterfly effect in chaos theory. The flapping of the wings of a butterfly can change the weather patterns.”

You gently touch some golden stonecrop forming a mosslike mat on the huge rocks. “We’re eight miles north of Salisbury, England.”

“Sir, you took us to Stonehenge?”

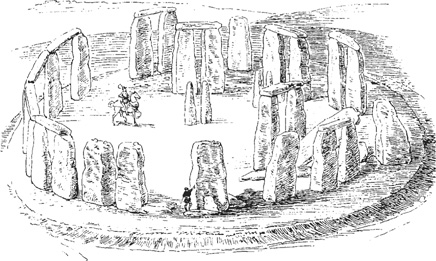

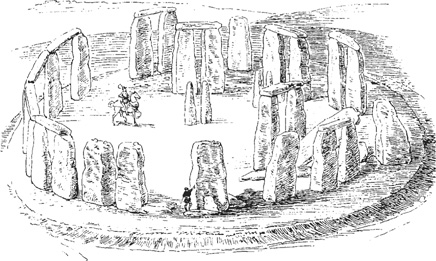

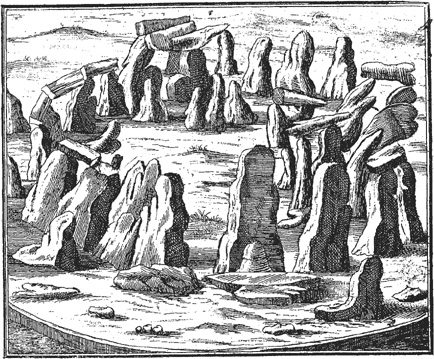

Earliest known perspective drawing of Stonehenge from a Dutch manuscript, 1574. (Early drawings have significant inaccuracies.)

You nod. “The ring of stones is about 350 feet in diameter.” You motion toward a gap in the circle of stones to the northeast. “That block of sandstone weighs 35 tons. And if my information is correct, we’re surrounded by an outer circular ditch and a ring of 56 pits.”

Theano lets out a whoosh of air. “Who built this? What’s it for?”

You start walking closer to the ring of holes as you turn back to Theano. “Probably a place of worship, but we don’t know much about the religion. Some of the stones are aligned on special areas of the horizon where the sun and moon rise at important times of the year.” You pause. “My opinion is that Stonehenge was a temple for sky worship. Most scientists believe it flourished as a temple or meeting place for more than one thousand years.”

Mr. Plex’s legs sink slightly into the sod. “Sir, why speculate? Why don’t we just go back in time to whenever people worshiped here and find out?”

“I don’t want to risk another disruption of the distant past.”

Mr. Plex nods. “We did cause quite a stir in ancient Greece.”

You nod. “Maybe the transfinites will leave us alone if we stay away from people.”

Theano slips her hand through the crook of your arm. “Which way do we head?” she asks, moistening her lips.

You shift the statue of Dionysus from your left to right hand.

Theano wrinkles her nose. “Do we have to keep that?”

You shrug. “Follow me.”

You lead Mr. Plex and Theano to a ring of pits, stoop down, and gaze into a dark hole. “These 56 pits are known, after their discoverer, as Aubrey holes.”

Mr. Plex’s eyes seem to glaze over. “56. A very interesting number. It’s the 6th tetrahedral number. The sequence is: 1, 4, 10, 20, 35, 56, 84, 120 … with a generating formula (l/6)n(n + l)(n + 2).”

You put up your hand. “That’s all very well and good Mr. Plex, but I don’t think it has much to do with Stonehenge.”

Mr. Plex ignores you and looks at Theano. “Consider an example using cannonballs. The number of balls in each layer is, starting from the top of the pile, 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, … which forms a sequence of triangular numbers because each level is shaped like a triangle. Tetrahedral numbers can be thought of as sums of the triangular numbers.”

You clap your hands together. “Mr Plex!”

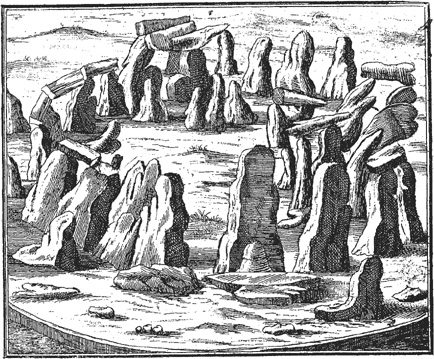

Stonehenge drawing from Camden’s Britannia, 1586.

“One minute sir.” He pauses. “We can extend the idea into higher dimensions, into hyperspace.” He says the word “hyperspace” with a trace of awe. “In 4-dimensional space, the piles of tetrahedral numbers can themselves be piled up into 4-dimensional hypertetrahedral numbers: 1, 5, 15, 35, 70.… We can form these numbers from the general formula: (l/24)n(n + 1)(n + 2)(n +3).”

You decide that the best way to stop Mr. Plex is by whispering just a few words. You motion to one of the Aubrey holes and say, “There are legends of treasure inside …”

Theano quickly reaches inside one of the pits.

You pull her hand out, crouch low, and begin to place your hand in the pit’s murky interior. “Wait. Let me make sure it’s safe.”

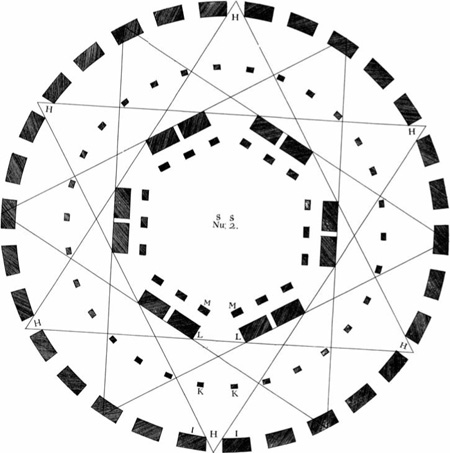

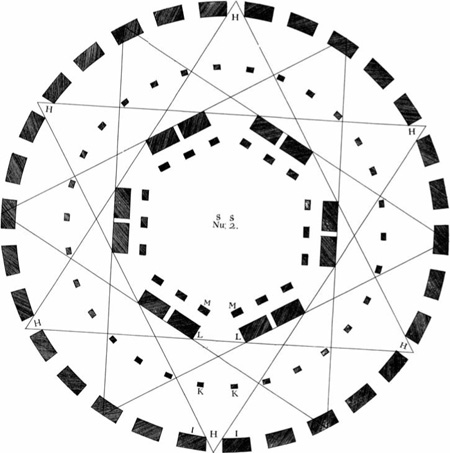

Drawing by Dr. Charleton, 1663.

“The hell with that,” Theano says. “Let me see what’s in there.”

Now Theano pulls your hand out of the hole, reaches inside, and brings out some grey, gritty powder.

Your left eyebrow raises. “Cremated burial remains and bones.”

Theano’s eyes open wide with horror as she throws dried adipocere’ at you.

You turn to Mr. Plex. “Even though two-thirds of the excavated Aubrey holes contain cremated human bones, the purpose of the holes is not necessarily sepulchral. In fact, you can find other cremated burial remains in the bank and in the silting around the ditches.”

Theano takes a deep breath. “Where are all the other holes?”

You glance at tiny bone fragments in the hole and then look at Theano. “Holes 33 to 54 have never been excavated. Their locations are known by bosing—sounding the ground with a large hammer and listening for soft spots.”

“Sir, if the holes aren’t some kind of burial pits, what are they for?”

“Some scientists say the holes, as well as the stones, function as a computer or counting device.”

“You mean Stonehenge is some kind of Stone Age computer?”

You nod. “Four station stones mark the winter and summer sun. They also mark the moon through all turning points of the 56-year moon cycle. The critical sunrises, moon-rises, sunsets, and moonsets are framed by the archways of the sarsen—the large boulder—circle as seen through the trilithons.”

Mr. Plex ambles closer to some large stones. “Trilithon?”

You motion to the structures consisting of three large stones: two upright and one resting upon them as a lintel:

“That’s interesting,” says Theano, “but how does that make it a computer?”

You nod. “I’m getting to that.”

Mr. Plex comes closer. “How old is this place?”

“Humans were constructing and altering Stonehenge for over five centuries—about 25 generations.” You motion all around you. “All of this was begun in the same millennium as the Great Pyramid of Giza, a few centuries before Abraham dwelt in Canaan!” You pause. “The Aubrey holes date back to 1800 B.C.” You point to tall blue rocks. “Those pillars, called bluestones, were brought here in the 17th century B.C.”

You walk to a circle of 30 upright stones capped by a continuous ring of stone lintels enclosing a horseshoe formation of five trilithons. From your history books, you know that the uprights are 30 feet long and weigh 50 tons.

Theano tugs at your hand. “Why did you call it a computer?”

“Stonehenge was built with its central axis pointing to the midsummer sunrise. It was a giant calculator for predicting solar and lunar eclipses. Several researchers say that Stonehenge builders had a knowledge of Pythagorean geometry 3000 years or more before the Greeks.” You pause. “Look at this. The archways and stones point to the rising and setting of the sun and moon at critical dates of the year. For example, the Moon rises farthest to the north when it appears over that stone as seen from the center of Stonehenge.”

Mr. Plex’s abdomen is pulsating. “It could predict eclipses? Imagine what fear a Stonehenge reader could cause if he could predict and seemingly control eclipses. Maybe a priest would strike terror in his people.”

“A Professor G. S. Hawkins in the 1960s showed how Stonehenge might be used as a computer to predict the time when eclipses of the Sun and Moon were due. He ingeniously related the 56 Aubrey holes with a 56-year eclipse cycle. Hawkins also suggested that cremations were performed in a particular Aubrey hole during the course of the year as a kind of bookkeeping system!”

You take a deep breath, trying to recall Hawkins’ words. “Here is a typical recipe Hawkins gave for using this Stone Age monument as a digital computer:

Take three white stones, and set them at Aubrey holes 56, 38, and 19. Take three black stones and set them at holes 47, 28, and 10. Shift each stone one place around the circle every year, say at the winter or summer solstices. This simple operation will predict accurately every important lunar event for hundreds of years.

“It’s all Greek to me,” Theano says tossing up her hands.

You smile. Evidently Theano is catching on to the idioms she hears from you.

“The point is that the monument could certainly form a reliable calendar for predicting the seasons. It could also signal the spooky periods for an eclipse of the Sun or Moon.”

“Sir, humans have always held eclipses in awe—sudden darkness at noon as the Moon blots out the Sun, the orange glow of the Moon in the Earth’s shadow.”

You nod. “Stonehenge wasn’t the only great stone monument. Humans built monuments like Stonehenge all over Europe, until about 1000 B.C. People may have continued to congregate and worship at the stone rings, and its possible that a Druidic priesthood used them as temples.”

“Druids?” Theano asks.

A shiver seems to run up Mr. Plex’s spine. “Sir, they were disgusting.”

“Ancient Celts. Priests. Sorcerers. They believed in reincarnation.” You pause. “They weren’t the nicest guys in the world. The Druids sacrificed humans to help others who were sick or in danger of death in battle. Huge wickerwork sculptures were filled with living men and then burned. Although the Druids preferred to burn criminals, innocent people were burned if criminals were in short supply.”

Theano shudders. “What stone is this?” she asks as you walk toward the north.

“Ah, the slaughter stone. See the channels on the rock?”

She nods.

“Through the channels ran the warm blood of Druid victims.”

Theano’s eyes open wide. “Really?”

You wave your hand. “Just kidding. Most likely the channels are natural to the rock. Even so, the name ‘slaughter stone’ is still used.”

Mr. Plex, in his excitement, suddenly bangs his massive body into one of the trilithons. It falls into its neighbor and, one by one, in a massive domino effect, all the remaining trilithons start crashing to the ground. The reverberations echo through the hillsides as dust and debris ascend like a phoenix rising from the ashes.

“Mon Dieu!” Mr. Plex screams looking at the chaos around him. “What do we do now?”

You are quiet, calm, always in control. “Can you put the stones back the way they were?”

Mr. Plex eyes the massive stones. “I can try.”

Theano and you watch as Mr. Plex drags the stones into position, occasionally uttering strange grunts signifying his awesome effort. Even the most proficient human sopranos or basso profundos are limited in the range, duration, and timbre of their voice due to the physical constraints of their vocal apparatus. Mr. Plex, a scolex, has no such limits. His grunts and groans are like a dozen bassoons filled with whipped cream.

After several hours of abdomen-breaking work, Mr. Plex repositions the last of the trilithons. “I think I got most of it right,” he says.

You nod. “We better get out of here. The transfinites aren’t going to like this one bit.”

THE SCIENCE BEHIND THE SCIENCE FICTION

Stonehenge would be functioning quietly and unnoticed as it had for the past 4000 years, a lonely monument to the scientific ability of prehistoric man.

—Gerald Hawkins, Beyond Stonehenge

Architect Inigo Jones’ Stonehenge drawing. He incorrectly shows a hexagonal figure based on 12-pointed star. What is the length of the side of the internal 12-sided isogon, if the side of the equilateral triangle is 1 unit? (Most mathematicians to whom I spoke suggest that the answer is  —

— . The edges of the interior regular 12-gon are of length 2

. The edges of the interior regular 12-gon are of length 2 —1.

—1.

All information on Stonehenge is based on current scientific documents (see References). The cremated remains of human bodies have been found in the Aubrey holes. Various authors have speculated as to the possible astronomical significance of the placement of stones within Stonehenge.

Druids did exist, although most of what we know about these priests and learned class of Celtic people is derived from secondhand Greek, Roman, and medieval Irish sources. Caesar referred to Druids as priests, religious ministers, or teachers. In native Irish and Welsh legends, the Druids are magicians and sorcerers. Like the Pythagoreans, the Druids’ principle doctrine was that the soul was immortal and passed at death from one person into another. Ironically, the Druids’ sacrificial rites were conducted with living people placed in huge wicker cages and burned. I find this difficult to understand considering that a Druid individual must have realized that this practice insured an individual would eventually be burned alive in a later incarnation.

How did the Druids get their name? Because the oak was sacred to the Druids (as was the mistletoe), the term “Druid” may be derived from the Celtic word for oak tree, daur. Incidentally, there was also a lower ranking Druidic priesthood, the vates, who were prophets and bards.

The legends of the Druids were preserved in Irish epics for several centuries after the Christianization of Ireland. There are faint undercurrents in Welsh folklore. The doctrines of the Druids seem to have disappeared from Europe in the early Middle Ages. In the 17th century, scholars believed that the Druids had constructed Stonehenge, but now we believe Stonehenge is of earlier origin.

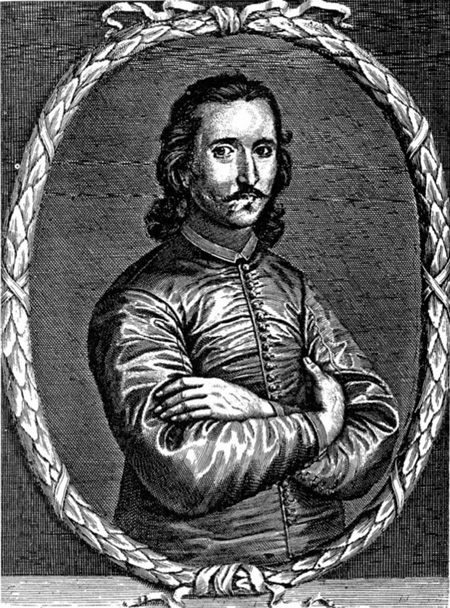

Famous Stonehenge explorer Inigo Jones (1573–1652), architect to James I and Charles I. (See his drawing on page 141.)

Stoneheiige explorer Walter Charleton, M.D., physician to Charles II. (See his drawing on page 138.)

Look round the world: contemplate the whole and every part of it; you will find it to be nothing but one great machine, subdivided into an infinite number of lesser machines … We are led to infer that the Author of Nature is somewhat similar to the mind of man.

—David Hume

—

— . The edges of the interior regular 12-gon are of length 2

. The edges of the interior regular 12-gon are of length 2 —1.

—1.