Viracocha, Lord of the Universe! Whether male or female, commander of heat and reproduction, being one who even with his spittle, can work sorcery, Where are you? The sun, the moon; the day, the night; summer, winter, not in vain hut in orderly succession do they march to their destined place, to their goal.

—Inca prayer to a cosmic god

They have their quipoes, which is a sort of strings of different bigness in which they make knots of several colours, by which they remember.… When they go to confession, these quipoes serve them to remember their sins.

—Churchill’s Voyage III, 1704

History has been written with quipo-threads.

—Carlyle, 1857 |

|

Theano places some kindling in an Aubrey hole and puts a few cedar sticks and branches on top. “Tetraktys,” she whispers as she throws a match into the pit. In a few seconds, the kindling is crackling.

Theano stares into the fire as it grows brighter, tongues of fractal flames licking the dried bark of the branches.

The fire is blazing now, the delicious aroma comforting you as the skeletal branches are engulfed in bright amber flames. But you feel as if you are in a trance. Even your own breathing seems too slow and strange. And you aren’t sure now that your voice is audible.

Slowly Mr. Plex sits down on the warm sod beside a large Stonehenge rock. He peers into the shadows beneath the arch of the trilithon.

You hear Theano sighing again, but it is soft and quick, like the wind. She rests against the stone, basking in the heat of the fire, her eyes wide as she gazes into the play of lights on the rocks. It seems she has been here forever.

You break out of your trance and toss a colored, knotted cord to Mr. Plex.

He catches it and studies it with his multiple limbs like a spider spinning a web. “What is it?”

“It’s a quipu. From the ancient Incas.” You pronounce it “kee-poo.”

Mr. Plex hands it to Theano who stares at the complex arrangement of knots.

“Incas?” she asks.

“Five million people who lived from A.D. 1400 to A.D. 1560 in what is now Peru, and also in parts of modern Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina.”

Seeing the confusion in Theano’s face, you sketch a map of the world in the sand and point to South America.

“They had a developed civilization—a common state religion, a common language. Although they didn’t have writing, they kept extensive records encoded by a logical-numerical system on the quipus.”

Inca holding a simple knotted quipu. At the lower left is a binary colored counting device with a “memory” of 20 compartments.

Theano begins to play with the intricate arrangement of cords. “Why’d they need to keep complicated records?”

You toss a branch into the fire. “The Incan governmental bureaucracy kept careful records on the goods they redistributed from their storehouses to their army. They encoded and decoded a tremendous amount of information using the quipus.”

Theano begins to count the knots in the quipus.

Your tone turns sad. “Unfortunately, when the Spanish came to South America, they saw the strange quipus and thought they were the works of the devil. The Spanish destroyed thousands of them in the name of God, and today only about 500 quipus remain.”

Theano holds up the quipu. “Where’d you get this one?” The quipu’s multiple cords trail beneath her slender hand like a living octopus.

“I had an excavation mole locate one underground. All of the quipus we have today were recovered from graves, probably buried with those who made them.”

A shudder runs up Mr. Plex’s abdomen. “I hate those excavation moles. Once one crawled down my alimentary canal. Had a hell of a time trying to get it out.”

Theano turns to you. “How does it work?”

“A quipu has a main cord from which the other cords are suspended.” You point to the large primary cord. “Most of the attached cords fall in one direction and they’re called pendant cords. A few lie in the opposite direction and are called top cords.”

Theano pulls on a cord suspended from the pendant cords. “What do you call this one?”

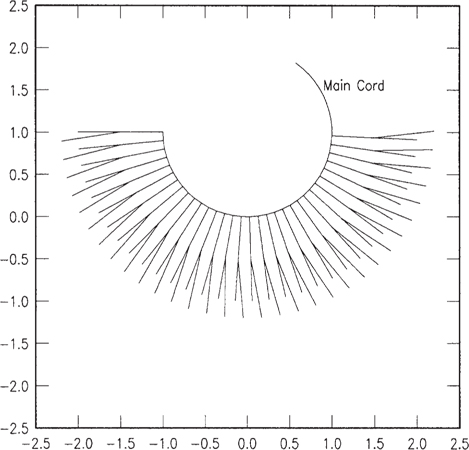

“Subsidiary cord. There can be subsidiaries on the subsidiaries forming a fractal Behold the branching pattern.” Fractal Quipu

You sketch in the sand.

You stand up and stretch your legs. “My excavation mole once unearthed a quipu with 18 subsidiaries on one level. The quipu had 10 levels of subsidiaries! The largest quipu found contained 1000 cords. The smallest 3 cords.”

Theano tugs at a knot. “What do the knots mean?”

“Knot types and positions, cord directions, cord levels, and color and spacing are all interpreted by the quipu makers to represent numbers.” You pause. “The knots were probably used to record human and material resources and calendric information. Some arche-ologists think that they contained more information: construction plans, dance patterns, and even aspects of Inca history.”

Theano nods.

“One sinister application of the quipu was as a death simulator.”

Theano wrinkles her brow. “What the Hades is that?”

“Yearly quotas of adults and children were ritually slaughtered. The whole thing was planned using a quipu—a cord model of the entire empire. The cords represented roads, and the knots were sacrificial victims.”

“Sick,” Theano whispers.

The fire is dying. Mr. Plex pokes at some of the burning branches creating a fountain of sparks. “Sir, did the Incas believe in God?”

You nod. “They believed that the creator resided in Tiahunaco where he turned men and women into stone for not obeying his commands. The creator was Ticci Virachocha, meaning the unknowable God. It was the Inca name for the ancient Peruvian sun god.”

Theano places the fractal weaving upon her neck. “We would make a killing selling these to the Pythagoreans.”

You smile as the number necklace dances upon her neck like a heavenly web.

“It’s getting mighty cold,” Theano says. “Look.” She holds out her arm. Flakes of snow land on her Greek robe.

“We had better get out of here,” you say. “This isn’t a good place to be in a snowstorm.” You gaze at the mutant Dionysus. “I think it’s time to leave Stonehenge.”

THE SCIENCE BEHIND THE SCIENCE FICTION

The Incas really used quipus, ancient memory banks for storing numbers, and the Spaniards really did destroy any quipus they found fearing they were the works of the devil.

Sixteenth century drawing of a simple quipu. Does the figure hint at some astronomical purpose for quipus?

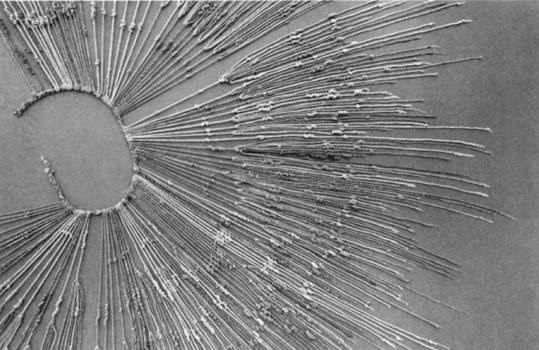

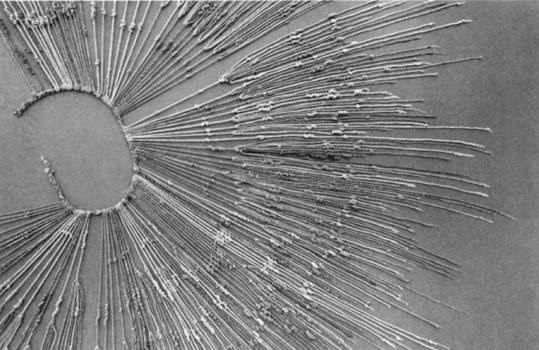

A quipu in the collection of the Museo National de Anthropologia y Arquelogia, Lima, Peru. Photo by Marcia and Robert Ascher.

Also, the quipu human sacrifice simulator is well documented. The top figure on p. 164 is a 16th century drawing of a simple quipu, and the bottom figure is a photograph of an actual quipu.

Sometimes knots had different meanings, depending on which string they were located. For example, a knot on one string might stand for 10, a knot on another might stand for one. Did the quipus code for a certain astronomical period? Cosmic, magical numbers? The population of a village? All these applications are possible.

The Incas also used a kind of primitive computer. It resembled a box with 20 compartments placed in four rows of five (see p. 162). Black and white stones were placed in the compartments, and a compartment was considered filled when it contained 5 stones. In 1590, Padre Jose de Acosta watched the Incas manipulate this abacus-like device, and he drew a sketch. Unfortunately, the Padre could not decipher how the device worked. Today, we still are not sure of its use.

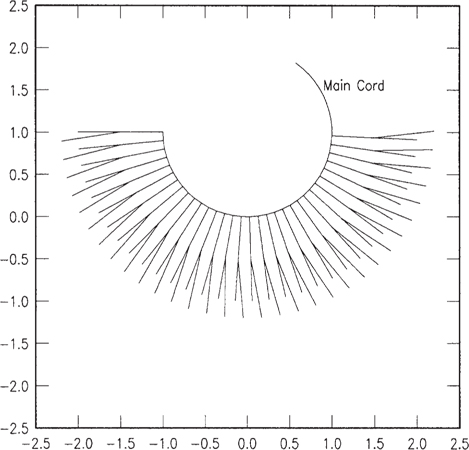

The Appendix contains a C program listing for producing points on a simple quipu. The points can be used to draw a quipu such as the one shown below.

Computer-generated quipu.

In this chapter, we’ve touched again upon ethnomathematics, the study of mathematics which takes into consideration the culture in which mathematics arises. Mathematics is associated with the study of “universals.” However, what we think of as universal is often colored by our cultural and historical perspectives. Various researchers believe that mathematics can be studied as a cultural development of structures and systems of ideas involving number, pattern, logic, and spatial configurations. Even the most basic of human activities often rely upon mathematics; these activities include: architecture, weaving, sewing, agriculture (requiring calendar systems and layouts for fields), kinship relations, ornamentation (such as tilings in the Islamic world and Native American beadwork), and spiritual and religious practices which are often associated with patterns in nature or ordered systems of abstract ideas.

The quipu was used around 1000 years ago. This means that the quipu is one of the most ancient methods of useful codification in the New World. The Incas had a highly ordered civilization as exemplified by their quantification of the planting of crops, behavior of the armies, output of gold mines, census results, composition of work forces, amount and kind of tributes, the contents of storehouses—and all these items were all recorded on the quipus.

When power was transferred from one Inca emperor to the next, information stored on quipus was used to recount the accomplishments of the leaders. Interestingly, today there are computer systems whose file managers are called quipus, no doubt in honor of this very useful and ancient device.