|

If you were a research biologist from the Stone Age, and you had a perfect map of DNA, could you have used it to predict the rise of civilization? Would you have foreseen Mozart, Einstein, the Parthenon, the New Testament?

—Deepak Chopra, Ageless Body, Timeless Mind

Was there meaning in the geometry, magic beyond magic? Was there a cave rabbi who could read the kabala?”

—Gerald Hawkins, Beyond Stonehenge, 1973

La Pileta was more numerical than artistic, more mystical than real. If rows of dots, strings of vertical dashes, and pairs of strokes were numerical, then La Pileta was a number cave.

—Gerald Hawkins, Beyond Stonehenge, 1973 |

You shine the light into the crevice. “Follow me. We’re going to look at something made around 20,000 B.C.” The surface of the cave walls are tan, glittering with gypsum crystals. The air smells clean and wet, like hair after it is freshly shampooed.

Huddled together like little hobbits, the smaller stalagmites of calcite cluster near a clear pool. The larger ones looked like rib bones of some giant prehistoric creature.

“Sh-Shall we go in?” Mr. Plex asks.

The wind sings through the stalactites like a large bird.

You put one foot into the crevice. “Sure, I have something wonderful to show you.” The cave throws your voice back at you, hollow and spooky.

You shine the flashlight all around. “Incredible,” you say. Glittering blue gypsum chandeliers, at least 25 feet in length, are suspended above your heads. Walls encrusted with fragile violet aragonite “bushes” line your path. With just a few steps, you have entered another world.

Theano walks over to a shimmering lake. A gentle breeze paints swirls and eddies on its surface.

You follow, careful not to lose your footing on the slippery cave floor.

The lake has a dank odor and the smell of life. Could any fish live in such a place? You walk closer to the edge of the lake. “Brrr,” you say with a shiver. The air is so cold that your breath sometimes steams. “Must be 100 percent humidity.”

Your gaze drifts to the pockets of crystals surrounding you. There is a flowing harmony of fractal formations and crystalline outcropping of rock coated with strips of velvet purple. A cool peace floods you, and for a second your concern about the transfinites and your preoccupation with the End of the World ebb away.

Theano places her finger in the lake. It is perfectly black down below.

You look off over the water. It is clear now, in the light of the flashlight, and filled with quartz nodules. You blow on the water, and countless ripples appear on its surface.

“Follow me.”

Mr. Plex’s forelimbs are quivering. “Sir, it’s a bit dark in here.”

You lead Mr. Plex and Theano deeper into the cave, several hundred yards into limestone rock, and then a hundred feet down.

Theano turns back to you. “Where are we anyway?”

“The cave of La Pileta, 40 kilometers from the Spanish Mediterranean.”

Upon scaling a 5-foot-high dirt wall in the middle of the passageway, you discover piles of human skulls scattered across the ground.

“Look,” Theano says as she points to limb bones stacked in piles.

You stoop down. “Interesting. It suggests that the cave was a secondary burial sight. The bodies were probably first buried elsewhere until the flesh decayed, then taken to the cave for permanent burial.”

“Creepy,” Theano whispers.

“Sir, I’d love to gather some bone and charcoal samples for radiocarbon dating back at our ship.” Mr. Plex brings out a backpack and stuffs a leg bone into it.

You nod. “Maybe we can do some DNA studies on the bones to figure out if the burial contained dead from the same households.”

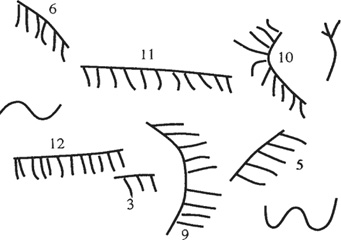

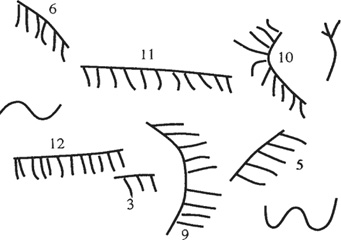

You shine the flashlight on the wall. “Ah, no where’s why I brought you!” You point to parallel marks, groups of five, six, or higher numbers. Clusters of lines are connected across the top with another line, like a comb, or crossed through in a way reminding you of the modern way of checking things in groups of five.

Theano goes closer to the wall. “Were they counting something?”

“I’m not sure. This certainly contradicts old-fashioned notions that cavemen of this period made guttural noises, and were only concerned with feeding and breeding. If the people who drew these designs mastered numbers, cavemen had intellects beyond the minimal demands of hunting.” You pause. “Higher thinking.”

Designs on the wall of the Number Cave. Some researchers believe the markings represent numbers. If you were to explore the cave and consider the teeth of the “combs” as units, you could read all numbers up to 14. In one area of the cave, the numbers 9, 10, 11, 12 appear close together. Could it be that the artist was counting something, recording data, or experimenting with mathematics?

Mr. Plex taps his forelimb on the wall. “Still they could just be abstract designs.”

“Correct, but if we still regarded Mayan friezes and decorated pyramids as merely art, we’d be wrong. Luckily, mathematically minded scholars studied them and discovered their numerical significance.”

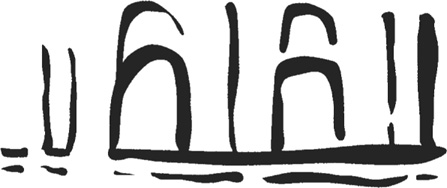

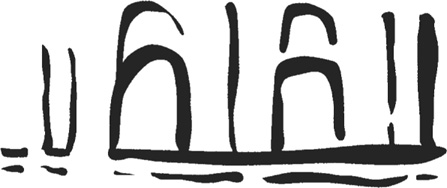

Theano points to an abstract design. “What’s this?”

“No one knows. A house with arched doorways? Flat feet? An astronomical symbol?”

Theano shivers. “Let’s go to the mouth of the cave and make a fire.”

You nod. “Good idea.”

After a few minutes Theano has gathered dead spruce branches festooned with lichen. You toss a match, and soon a warm fire is burning.

You close your eyes for a second. Even the faint dripping sound is music. You have longed for this fragrant and embraceable coolness with your soul. Is there anyplace else in Spain, the world, where the moist air feels like a living presence, where the cold air brushes against you like cats, where the stalactites and slippery cave walls are shimmering and alive?

Can Theano feel what you are feeling? Can she appreciate the majesty and mystery of this Stygian chamber? You have the urge to squeeze her hand, hold her close. You’ve always fallen for the helpless, the ones who were lost or in trouble. And you always regretted getting involved. Why do you always insist on rescuing a damsel in distress? This doesn’t seem like the time for romance. Theano is too vulnerable, from a different time, worried about the world. What kind of man could think of her in romantic terms at a time like this? You feel a twinge of shame. But at least you are together.…

Her eyes are unfocused as she trails her fingers along a stalagmite.

“What are you thinking?” you ask.

“The things you’ve shown me. The fractals, the quipu, this number cave. Stonehenge, the golden ratio, the Urantia, perfect numbers. Humans have always intertwined mathematics with the divine.”

You nod. “Mathematics is the loom upon which God weaves the fabric of the universe.”

THE SCIENCE BEHIND THE SCIENCE FICTION

Number Caves

The cave of La Pileta is 40 kilometers from the Spanish Mediterranean and discussed by Hawkins (see References). The comblike markings you showed to Theano and Mr. Plex really do cover the wall. Some archeologists believe that the markings represent numbers, but we cannot be certain.1

The arched doorway diagrams that Theano discovered exist, but their meaning is unclear. What do you think they represent?

The Loom of Computers

Cave wall numbers were some of the initial steps toward primitive computing machines. One of the first true calculating machines to help expand the minds of humans was the abacus. The abacus is a manually operated storage device which aids a human calculator. It consists of beads and rods, and originated in the Orient more than 5000 years ago. Archeologists have since found geared calculators, dating back to 80 B.C., in the sea off northwestern Crete. Since then, other primitive calculating machines have evolved, with a variety of esoteric sounding names, including: Napier’s bones (consisting of sticks of bones or ivory), Pascal’s arithmetic machine (utilizing a mechanical gear system), Leibniz’ Stepped Reckoner, and Babbage’s analytical engine (which used punched cards).

Continuing with more history: the Atanasoff-Berry computer, made in 1939, and the 1500 vacuum tube, Colossus, were the first programmable electronic machines. The Colossus first ran in 1943 in order to break a German coding machine named Enigma. The first computer able to store programs was the Manchester University Mark I. It ran its first program in 1948. Later, the transistor and the integrated circuit enabled micro-miniaturization and led to the modern computer which today is of central importance to many researchers exploring the mathematical loom of the universe.

In the mid-1990s, one of the world’s most powerful and fastest computers was the special purpose GRAPE-4 machine from the University of Tokyo. It achieved a peak speed for a computer performing a scientific calculation of 1.08 Tflops. (Tflops stands for trillion floating point operations per second.) With this computer, scientists performed simulations of the interactions among astronomical objects such as stars and galaxies. This type of simulation, referred to as an N-body problem because the behavior of each of the N test objects is affected by all the other objects, is particularly computation intensive. GRAPE-4 reached its record speeds using 1692 processor chips, each performing at rates of 640 Mflops. Like a web spun by a mathematically inclined spider, each processor had intricate connections with one another. The Tokyo researchers hoped to achieve petaflops (1015 operations per second) by the turn of the century with a suite of 20,000 processors each operating at 50 Gflops. GRAPE-4 is certainly much more expensive than the abacus or Napier’s bones, but also much faster!