Chapter 10

![]()

BANISHMENT

In the wake of his failure to secure passage of his bank bill, Henry Clay was forced to accept that the optimism he entertained about the president before the special session began had been unfounded. He now saw Tyler for what he was: the major impediment to the creation of a truly national bank and a threat to the entire Whig agenda. “Is it not deplorable that such a cause should be put in jeopardy in such a way!” he shrieked. Clay sensed that Tyler had begun to isolate himself from the prevailing views of both the Whig and Democratic Parties. “He conciliates no body by his particular notions,” the senator argued in frustration. “The Loco’s [Democrats] are more opposed to the scheme [the administration bill and the Rives amendment] than to an old fashioned bank, and ninety nine out of a hundred of the Whigs are decidedly adverse to it.”1

Clay’s analysis spoke to a developing political situation, the full importance of which he apparently did not yet grasp. Tyler’s stance puzzled him. If the president’s “notions” pleased neither Democrats nor Whigs, what could he possibly hope to accomplish politically by sticking to his guns? What Clay failed to realize was that Tyler saw the impending fight over the bank as the opening salvo in his campaign for the presidency in 1844 and hoped this fight would allow him to build a political base for that election.

Tyler’s friends in Virginia—Beverley Tucker and Abel Upshur—made the urgent case for a states’ rights party. Congressman Wise also kept the pressure on the president with regular visits to the White House. To this chorus, Governor Rutherfoord of Virginia added his thoughts as he sought to encourage Tyler for the fight ahead. “It appears to me,” he wrote on June 21, “that a bold effort is about to be made to revive the system and principles of [Alexander] Hamilton, and that it becomes all who regard themselves as the disciples of the Jeffersonian school, and would defend State-rights against consolidation, to take a decided stand against the encroachment of Federalism.” Rutherfoord expressed his concern about the president’s cabinet (this was a constant refrain of Tucker and Upshur too) but acknowledged that “accident” had thrown Tyler and them together. “With your principles,” he declared, “you could never have called such men around you.” Webster and the other members of the cabinet were not to be trusted, nor was Clay. Rutherfoord made clear, however, that there were men Tyler could trust, “none on whom you can rely with so much safety as those old State-rights Republicans (whether Democrats or Whigs) who stood by you in times gone by.”2

Tyler appreciated the support. As president, however, he had the responsibility to see the many layers of the politics of the bank issue and to understand the complexities of what he was tasked to do. While he appreciated the stance that Tucker, Upshur, Wise, and now Rutherfoord had taken on the Whig efforts to recharter a national bank, Tyler did not have the luxury of pursuing the rigid course they favored and hoped from him. He was utterly refusing to play the part of ideologue; it would do him no good. In that sense Upshur’s chronic handwringing and his belief that Tyler would disappoint them had merit. Those closer to the situation had an even better idea of what Tyler was attempting to do. John C. Calhoun, for example, argued that the president was “essentially a man for the middle ground.” While he questioned the wisdom of an attempt to stake out a position between the Clay Whigs and the Democrats, Calhoun accurately predicted in mid-June that Tyler would “attempt to take a middle position now.”3

The president sought every opportunity to make common cause with the Whigs. On July 21 he signed a bill into law that allowed the federal government to borrow up to $12 million through the sale of US Treasury bonds, a bill Clay had largely shaped and one both he and Tyler believed essential to the government’s ability to conduct its business. The bank bill, of course, was the main attraction, what Clay had decided over the objections of Tyler would be the signature piece of legislation of the special session. The Kentuckian was determined to get it.

Clay sent Virginia congressman John Minor Botts up Pennsylvania Avenue to feel out the president and determine whether he would be amenable to an idea circulating in the Whig caucus that party leaders believed might break the impasse over the bank. Called the “Bison” by his peers for his chronically unshaven face and unruly mop of hair—and described as a “bull-dog, always barking,” by one historian—Botts was on friendly terms with Tyler. The proposal he brought with him, however, did not pass muster. The president called it a “contemptible subterfuge, behind which [I] [will] not skulk.” Whigs wanted to allow the national bank to establish branches in any state as long as the legislature of that state did not explicitly disapprove at its first session after the bank bill had been signed into law. Further, even if a state refused permission to establish a branch within its borders, Congress could override the legislature and authorize a branch if it was deemed necessary and proper for the public interest.4

Why Clay, Botts, or any Whig believed this proposal would receive the president’s sanction is difficult to fathom. Tyler later claimed that he let Botts know he would veto a bill that included these provisions. Incredibly, however, Botts informed Clay that the president had accepted the proposal! Perhaps Tyler had not made his intentions entirely clear. Perhaps Botts, for whatever reason, lied. Whatever the case, Clay then offered the proposal as an amendment to the original bank bill and was able to shepherd the revised legislation through both houses of Congress. The White House received the bill on Saturday, August 7, 1841.5

So now the matter was in the hands of Tyler. The entire cabinet urged him to sign the bill, but there seemed little doubt as to what he would actually do—most people expected him to use the veto. Nevertheless, suspense hung over Washington. A “commotion” over the issue had taken hold in the city, one observer reported. “The veto anxiety absorbs all thought & attention,” said another. Peter Porter, a close political ally of Clay from western New York State, wrote that there was “a most agonizing state of uncertainty in the public mind.” Moreover, he saw, as Clay did, that Tyler could potentially snuff out the entire Whig agenda. “It is impossible to foresee the tremendous consequences of a Veto. If the bill should be approved, we shall probably carry all our great measures; if rejected, we may lose most of them.” Clay acknowledged the stress on himself and on the party. “We are in painful uncertainty as to the fate of the Bank bill,” he acknowledged.6

Tyler seemed in no hurry to decide his course of action. The Constitution grants the president ten days before he must either sign a bill into law or send it back to Capitol Hill with a veto message and his objections. If he neither signs a bill nor vetoes it within ten days, it automatically becomes law without his sanction or official disapproval. Tyler apparently intended to take the full constitutional allotment of time to make up his mind. Some, like Upshur, took this as a sign of the president’s vacillation and indecision. “I do not believe that he knows what he himself will do,” Upshur asserted, growing more anxious and more annoyed with each passing day. Most observers, however, seemed to think that the delay meant a veto for sure.7

A portent in the weather added drama to the uncertainty over a potential veto. Amid the heat and humidity of a typical Washington summer, a tornado touched down near Pennsylvania Avenue at about 2:00 P.M. on August 11, tearing the roofs off buildings and scattering debris everywhere. The White House escaped unscathed. People at the Capitol, dumbfounded, were able to watch the entire meteorological event unfold, and “at that place not a breath of air was to be felt, & so everybody said it was the veto message coming.” The anticipation over the president’s decision and the constant prattle of the politicians and other city residents about it made it appear almost as if the veto was “some great beast, like that spoken of [in] Revelation,” that would “come raving and tearing along the Avenue.”8

Tyler finally executed his constitutional duty on August 16, nine days after he had received the bill from Congress. He vetoed the measure. John Tyler Jr., serving as his father’s private secretary, was tasked with taking the veto message to the Senate chamber that morning. Dozens of spectators who could not secure seats inside milled about outside in the corridor and at the door, so John had to fight his way through them to hand the message to the sergeant-at-arms. The chamber itself was practically silent, as senators and onlookers craned their necks to see what was going on and readied themselves for what they were about to hear. By the third sentence of the message—“I can not conscientiously give it my approval”—hisses and catcalls cascaded down to the floor from the galleries above. Some of the spectators booed lustily. Thomas Hart Benton, of all people, now suddenly the guardian of decorum, jumped to his feet and shouted above the noise for the “Bank ruffians” and “hooligans” to cease their racket and stop insulting the president of the United States.9

The rest of the veto message did little to quiet the Capitol denizens in the Senate chamber galleries, most of whom were apparently Whig in their partisan orientation. Sitting at his desk, Clay stared straight ahead, listening with no apparent emotion, betraying no surprise—but his worst fears had now come true.10

So what argument had the president made in defense of his veto? Early in the message, Tyler called the constitutionality of a national bank an “unsettled question.” Such a statement obviously revealed that he did not regard the Marshall court’s decision in McCulloch vs. Maryland as having decided the issue of whether a bank could be chartered. This was a very Jacksonian stance, one that pleased many Senate Democrats. He also maintained that the American people were still “deeply agitated” and divided over the issue. Somewhat defensively, Tyler explained how his own opinion on the bank question had been “unreservedly expressed” for the past twenty-five years. In light of this long-held opinion, and given that his oath demanded that he “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution,” he could not sign the Whig banking measure into law “without surrendering all claim to the respect of honorable men.” Jackson had been absolutely right when predicting that Tyler’s honor would not permit him to sanction the bank bill.

More substantively, Tyler wholly objected to the part of the bill embodied in the amendment Clay offered to secure its passage in the Senate, the part Congressman Botts claimed had received the president’s approval. Tyler also fastened onto a more technical aspect of the bill and opposed granting branches of the national bank the authority to make local loans or discounts of promissory notes. State banks often printed and lent their own notes and commonly “discounted” the interest due on those loans, which meant the borrower would not be required to pay back as much money, an attractive option for someone engaged in commerce. A national bank would almost certainly be able to offer even greater discounts than its state counterparts, which would hamper their ability to offer credit. In effect, this would drive such state banks out of business. As Tyler made clear in his message to Congress before the special session began, he wanted only to rein in the state banks, not to completely destroy them.11

The veto drew condemnation from many in Whig quarters, while it energized the Democrats. “This extraordinary step of the President,” Peter Porter wrote Clay from Buffalo, “although long threatened, was never realized nor believed until this moment, and has excited universal dissatisfaction and even disgust among the members of the Whig party.” Whigs now realized they had a fight on their hands. Tyler had asserted his constitutional prerogative and defended his principles, which left party leaders scrambling to find a way to salvage their legislative agenda. It was shaping up as a battle of wills, and the president had maneuvered to give himself the upper hand.12

Still, most Whigs did not lose heart. They thought Tyler’s veto message was clear, to the point, and, at least to some in the party, not necessarily a fatal blow to their plans. The congressional caucus had met the night before the veto and discussed whether they should fall back on Ewing’s proposal—the administration bill. There was another plan in the works as well. A few short hours after Tyler’s message had been read in the Senate, the Whig caucus dispatched Virginia congressman Alexander H. H. Stuart to the White House, anxious to find out whether the president would accept a bank bill if the Whigs deleted the provision allowing branches to offer local discounts on promissory notes. Senator Richard Bayard of Delaware had offered just such a solution during the debate over Rives’s amendment on July 6, but nothing had come of it.13

Stuart reported that Tyler met him “in the proper temper” and “expressed the belief that a fair ground of compromise might yet be agreed upon.” The two men discussed some of the details of the just-vetoed bank bill, including the feature that allowed the bank to offer local discounts on promissory notes. According to Stuart, the president told him that if Congress would send him a bill that removed the authorization for agencies (or branches) of the bank to act in the states as offices of discount and deposit, he would sign it “in twenty-four hours.” Tyler would allow the bank to act as the fiscal agent of the government, receive deposits, circulate notes, and deal in bills of exchange, but he would not allow local discounts on promissory notes. Such a practice, again, would threaten the viability of state banks. Tyler also added that he would allow the proposed national bank to establish branches in the states unless they were “forbidden by the laws of the State.” Stuart later maintained that the president had grasped his hand as he prepared to leave and exclaimed, “Stuart! If you can be instrumental in passing this bill through Congress, I will esteem you the best friend I have on earth.” Tyler instructed him to seek out Secretary of State Webster to frame the new bill but made clear that he did not want to be portrayed as having dictated the terms of the new measure to the congressional leadership. As Stuart made his way out of the White House, he thought he might have succeeded in finding a compromise with the president that the Whigs could use.14

![]()

At 2:00 A.M. on August 17, the morning after the veto, President Tyler and his family were awakened by a raucous gathering of drunken Whig partisans who beat drums and shouted insults at the tops of their lungs from the lawn of the White House. This bunch had apparently not been privy to the negotiations between Stuart and the president the previous afternoon and had taken to the bottle in the wake of the veto, trying to come to terms with what had just happened. They now took out their wrath on the First Family. The president watched nervously from his window and was shocked to see the mob burn him in effigy. It seemed all of Washington had been turned upside down by the constitutional scruples of John Tyler.15

Later that morning, at a more congenial hour, the president received a visit from Whig senator John M. Berrien and Whig congressman John Sergeant, two vocal supporters of the kind of bank Clay wanted. They had come to find out whether what Tyler had tentatively agreed to with Stuart was still in force. Treasury Secretary Ewing called on Tyler while the two men were there. Waved into the office, Ewing took a seat. Tyler told Berrien and Sergeant that he “did not think it became him to draw out a plan of a bank, but he thought it easy to ascertain from the general course of his argument [in the veto message] what he would approve.” The president did not even mention the meeting with Stuart (did they ask about it?), leading the new emissaries to wonder how close Tyler and the party really were to working out some sort of an agreement. Ewing interpreted the conversation to mean that Tyler did not object to a national bank located in the District of Columbia, as long as it was not empowered to make local discounts on promissory notes.

Berrien and Sergeant returned the next morning, Wednesday, August 18, for a lengthier meeting with Tyler. He convened a meeting with his cabinet later that morning by telling them that he had refused to get specific with the emissaries over the details of a bank bill he could support. Tyler then asked the men to take seats around his desk and quickly got to the matter at hand. This was the first cabinet meeting since the veto message had been sent to the Senate, and there was a lot to discuss.16

Tyler claimed to be surprised by the dissatisfaction his veto had caused. Moreover, he was puzzled as to why the Senate had not yet formally responded. He had apparently expected that it would be taken up on the seventeenth, the day after the message had been read, but thus far Clay had bided his time, perhaps with the intention of finding out whether the Stuart mission or the visits by Senator Berrien and Congressman Sergeant could achieve a breakthrough. The silence from the Senate worried the president. He “expressed anxiety as to the tone and temper which the debate would assume there” once the Whigs formally addressed the veto.

Trying to allay Tyler’s fears, George Badger spoke first. “Mr. President,” he said, “I am happy to find on inquiry that the best temper in the world prevails generally in the two Houses on this subject.” He then informed Tyler that he believed the Whigs were “perfectly ready to take up Mr. Ewing’s bill and pass it without alteration except in some unimportant particulars.” This assertion provoked a rare outburst of ill temper from Tyler. “Talk not to me of Mr. Ewing’s bill,” he barked, “it contains that odious feature of local discounts, which I have repudiated in my message.”17

This was the first indication Tyler had given his cabinet that he no longer supported the administration bill Ewing had sent to the Senate on June 12. It appears that two considerations had changed his mind. First, he had heard grumbling from the Whigs that the administration bill was “declared to have arisen in a spirit of executive dictation.” Fear of just that kind of criticism had persuaded Tyler originally that a bank bill should come from Congress. He now regretted allowing Ewing to draft the administration bill and believed without question that a new measure had to at least have the appearance of congressional sponsorship. Tyler bristled that “the war is to be made not only upon my opinions, but my motives.” Second, conversations with Wise, in which the congressman had made clear his opinion that Clay would fall back on the Ewing plan in an attempt to play the role of “great pacificator,” had turned Tyler against his own administration’s effort. The president had said nothing about his objection to local discounts when he read Ewing’s draft initially. It appears that he was using this now merely as an excuse to justify killing all chances at reviving the administration bill. Revival would, according to Wise, play directly into Clay’s hands and strengthen his position in the party.18

There is also evidence that Tyler already knew what the Whigs had planned and that Badger’s statement in the cabinet meeting confirmed, rather than allayed, his worst fears. That would certainly explain his anger. According to Lyon G. Tyler, on the day of the veto, August 16, a gentleman of the “strictest veracity” wrote Tyler to explain what was afoot. “The caucus last evening,” he informed the president, “after much disagreement, came to the resolution to pass a Bank bill on Mr. Ewing’s plan. The object seems to be your destruction and a dissolution of the cabinet.” The letter continued, “They say that you and the cabinet stand pledged to support that scheme, and that you cannot now assent to it; ergo, a veto of that would place you fully in the arms of the Locos, and your cabinet would abandon you.” The author of the letter claimed that Congressmen William Russell of Ohio and John Taliaferro of Virginia were his informants and that John J. Crittenden was already making plans to resign his position as attorney general.19

Ewing, taken aback at both Tyler’s repudiation of the administration bill and the vehemence with which he had expressed his feelings, managed to find some words he hoped would placate the president. “I have no doubt, sir,” he said, “that the House, having ascertained your views, will pass a bill in conformity to them provided they can be satisfied that it will answer the purposes of the Treasury and relieve the country.”

Tyler looked at the men seated before him. “Cannot my Cabinet see that this is brought about?” he asked. Leaning forward in his chair, he told them that he needed their support. “You must stand by me in this emergency,” he said pointedly. “Cannot you see that such a bill passes Congress as I can sign without inconsistency?”

Ewing replied that he thought a bill which would satisfy the president may be introduced in the House very soon. “Of the Senate,” he admitted, “I am not so certain.” The Treasury secretary was unnerved by the way Tyler was conducting the meeting. The president was agitated; he did not seem himself. “If such a bill could pass both bodies speedily and receive your sanction,” Ewing continued, trying further to soothe his boss, “it would immediately restore harmony here and confidence throughout the nation.”

Tyler paused. “I care nothing about the Senate,” he stated emphatically, “let the Bill pass the House with the understanding that it meets my approbation and the Senate may reject it on their own responsibility if they think best.” The implicit message here was that Henry Clay would reject any bill receiving Tyler’s sanction and that Clay would suffer the consequences in the court of public opinion.

The president wanted to make certain that his cabinet understood exactly what he could support in a bank bill. He wanted there to be no misunderstanding between them. Tyler put Ewing on the spot and asked his Treasury secretary if he understood the type of bank bill that he could sign into law. “I understand you are of opinion that Congress may charter a Bank in the District of Columbia giving it its location here,” he said, no doubt thinking he would dispense with the most obvious point first. Tyler nodded impatiently and motioned for him to continue. “That they may authorize such Bank to establish offices of Discount and Deposit in any of the States with the assent of the States in which they are so established.”

Tyler exploded. “Don’t name Discounts to me,” he shouted angrily, leaping to his feet. “They have been the source of the most abominable corruptions—and they are wholly unnecessary to enable the Bank to discharge its duties to the country and the Government.”

Ewing gathered himself and told the president that he was “proposing nothing, but simply endeavoring to recapitulate what I have heretofore understood to be your opinion as to the powers which Congress many constitutionally confer on a Bank. I now understand your opinion to be, that they may not confer the power of local discount even with the assent of the States.”

Tyler gave a half-nod, indicating that Ewing now had it correct. The Treasury secretary bravely continued. “And I understand you to be of opinion that Congress may authorize such Bank to establish agencies in the several states with power to receive, disburse or transmit the public monies and to deal in Bills of Exchange without the assent of the States.” “Yes,” Tyler replied, calming down a bit, “if they be foreign bills or bills drawn in one State and payable in another. That is all the power that is necessary for transmitting the public funds and regulating exchanges and the currency.”20

Up to this point, the other men in the room had been silent, content to let Ewing bear the brunt of Tyler’s anger, perfectly willing to let him answer the questions the president posed. Webster, nursing the pain of his “rheumatic shoulder” recently aggravated by a carriage accident and a bit out of sorts because of it, did eventually weigh in on the matter. Tyler was interested to hear what he had to say.21

“I would like such a bill,” Webster began, “with power to deal in Exchanges alone, without authority derived from the States, much better than if it combined the power of Discount with the assent of the States, and the power to deal in exchanges without such assent.” He did not “think it necessary to give such Bank the power of local discount, in order to enable [it] to perform all its duties to the country and to the government, unless indeed it be essential to the existence of such institution.” Tyler cocked his head back, taking in what his secretary of state had just said. Webster continued, acknowledging that the president’s idea to prohibit local discounts was sound. But he asserted that he also believed a bank was necessary for safeguarding the government’s money and restoring a sound currency.

When Webster had finished, Tyler “expressed his acquiescence” and told the cabinet that he wanted them to devise a bill that “should assume that form.” He also wanted them to tap someone who was a friend of the administration to shepherd the bill through the House of Representatives. “Is Mr. Sergeant agreeable to you?” Ewing asked the president. Tyler indicated that the Pennsylvania congressman was acceptable but curiously (ominously?) added that he did not want the cabinet to commit him—Tyler—“as having agreed to this project.” He advised the men that they should, according to Ewing, “say that from the Veto Message and from all that we knew of his opinions we inferred that this would be acceptable.” He also instructed them to refrain from calling the proposed fiscal agent a “bank.” Some of the members objected to this condition, but they reluctantly agreed to do as the president wished. Tyler then quizzed Webster on the language he would use in providing the bank with branching power. When he was satisfied, he concluded the meeting by telling his cabinet that he found the entire matter bewildering. According to Ewing, the president “had no time to collect his thoughts” and wondered aloud why the bank bill could not be “postponed to the next session” of the Twenty-Seventh Congress.22

The answer to that question was simple: Clay and the Whigs in the House and Senate did not want the matter postponed. The senator had decreed at the start of the special session that Congress would address the nation’s financial predicament. That, in fact, was the sole reason for convening the special session in the first place. He stood firm in his belief that a robust national bank had to be the centerpiece of those efforts, and he would not allow the president to delay his plans. Politically, Clay realized that since he had set the agenda, he had to follow through or look as if he had lost control of his party.

![]()

On Thursday, August 19, Clay finally addressed Tyler’s veto in the Senate chamber. He did not have the votes necessary to override it, but he could make absolutely clear where he stood on Tyler’s use of executive power. In a methodical speech that lasted nearly ninety minutes, he denounced the president and castigated him for having “not reciprocated the friendly spirit of concession and compromise” with which Congress had passed the bill. Clay characterized the veto message itself as “harsh, if not reproachful.” He pointed out that Tyler had stated in his inaugural address that he would support any “constitutional” bank bill that came from Congress. The senator obviously believed his bill passed constitutional muster. Further, the president had promised to “resort to the fathers of the great Republican school for advice and instruction.” Clay had taken that to mean that “the president intended to occupy the Madison ground, and to regard the question of the power to establish a national bank as immovably settled.”

Clay argued that Tyler’s veto had thwarted the wishes of the American people. He exhorted the Whigs to keep up the fight and make good on the 1840 electoral mandate. When Clay finished speaking, Senator Rives took to the floor to defend the veto and the president’s character. Clay then eviscerated Rives and took aim at Tyler’s other supporters, “a new sort of kitchen Cabinet” he called them, recalling the men President Jackson had surrounded himself with a decade before. The Kentuckian did not doubt that these men sought to “place me in inimical relations with the President” and to “represent me as personally opposed to him.” They were “beating up for recruits, and endeavoring to form a third party, with materials so scanty as to be wholly insufficient to compose a decent corporal’s guard.” Characterizing Tyler as the “unfortunate victim” of his own pride and vanity, Clay maintained that this “corporal’s guard” found the president receptive to what they hoped to accomplish because he could not “see beyond the little, petty contemptible circles of his own personal interests.”23

The “corporal’s guard” comment was meant to belittle the amount of support Tyler had for his position on the bank as well as denigrate the quality of the men who supported him. Like most of the Kentuckian’s well-placed barbs, it worked. Insult aside, Clay’s comment contained some truth. Wise led a coterie of only six Whigs in the House of Representatives who were opposed to their party’s banking measures and who favored Tyler’s stance: Thomas W. Gilmer, George H. Proffit, W. W. Irwin, Francis Mallory, and Caleb Cushing.24 In the Senate Rives was solidly in Tyler’s corner, at least for the time being, with other Whigs such as William D. Merrick of Maryland, Alexander Barrow of Louisiana, William C. Preston of South Carolina, and John Henderson of Mississippi expressing their support for the president. Wise, as nearly everyone in the capital knew, was trying to portray Clay as personally opposed to Tyler. And he sought to sustain the president and encourage a break with Clay and the majority of the Whigs in Congress. The senator professed to be disturbed by this prospect. “If the President chooses,” he said, “which I am sure he cannot, unless falsehood has been whispered into his ears or poison poured into his heart—to detach himself from me, I shall deeply regret it, for the sake of our common friendship and our common country.”25

But it was not just Tyler’s friends who wanted to “detach” him from Clay and the majority of the Whig party. Tyler had made new enemies by wielding the veto pen. Congressman Botts was chief among them. On August 21 the Madisonian—a newspaper increasingly taking on the character of the administration’s mouthpiece—published a letter Botts had written and addressed to a Richmond coffeehouse on August 16, the day of the veto. “Our Captain Tyler is making a desperate effort to set himself up with the loco-focos,” the congressman wrote with utter disdain, “but he’ll be headed yet, and, I regret to say, it will end badly for him. He will be an object of execration with both parties[—]with the one for vetoing our bill, which was bad enough, with the other for signing a worse one.” Tyler was “hardly entitled to sympathy” for the position he found himself in, Botts declared. “He has refused to listen to the admonition and entreaties of his best friends, and looked only to the whisperings of ambitious and designing mischief makers who have collected around him.” Botts had proffered the compromise measure he brought to the president “to save him from the alternative of the veto.” Tyler, however, “lash[ed] them across the face with the instrument they had thus furnished him, and then attempt[ed] to turn the whole party of friends who placed him in power into ridicule.”26

Botts had set himself completely against the president. Tyler’s refusal to sanction the compromise his fellow Virginian had brought to the White House prior to Senate passage of the bank bill in August played a role in this. Still, he could not have predicted Botts would seek his revenge like this. The coffeehouse letter stung Tyler. He surely did not fail to note the sarcastic reference to his military service during the War of 1812—recall Tyler had attained the rank of captain in a Virginia militia company that saw no action. He also recognized that his enemies were assigning perfidy to his motives for using the veto on the bank bill. It was all too much—Botts had once been a friend!

Tyler had received a copy of the coffeehouse letter the night prior to its publication in the Madisonian and, after reading it, hurried over to Webster’s office in the State Department. The two men sat talking for an hour, and Tyler, nearly distraught, “complained very much of the ill-treatment” he was receiving at the hands of the Whigs in Congress. Webster wrote later that he “appeared full of suspicion and resentment.” The bank issue was clearly taking an emotional toll on the president.27

Tyler’s state of mind was important because, by August 20, a new bank bill was working its way through the House of Representatives, largely from the efforts of Webster and Congressman Sergeant. Tyler had insisted that his cabinet and the House sponsors not attach his name to the measure, known as the Fiscal Corporation Bill. There would be no official second administration bill. According to Ewing, “the President expressed great sensitiveness lest he should be committed by anything that he or we should say to a project which would not be accepted by Congress.” In other words, Tyler did not wish to be boxed in by Clay and the Whigs. Nor did he want to look like a fool for vetoing a bill he had sanctioned beforehand. Webster and Ewing complied with his instructions.28

Webster brought a copy of the bill to Tyler on the night of August 18, just before debate on the measure began in the House. The two men pored over it together. According to Webster, who would later compose a lengthy memorandum on the bank fight, Tyler “expressed no objection whatever” to the provision that allowed the bank and its branches to use bills of exchange. The president also “made no mention of the necessity of State assent, to a Bank carrying on Exchanges between the States.” Tyler did insist on striking the word “bank” from the legislation, preferring “Fiscal Corporation.” He also made clear that he wished its capitalization to be reduced from $30 million to $20 million or less and that he wanted the bank to be prevented from selling US stocks. Webster noted these changes on the bill itself and the next day took it to Sergeant.29

Tyler asked Webster and Ewing to give him their views of the new bill separately and in writing. Both men supported the measure and composed memoranda explaining their positions. Their support of the bill, however, had no effect on Tyler, who told two New York congressmen calling on him at the White House on the twenty-third that “he would have his right [arm] cut off, & his left arm too, before he would sign the Bill then pending” in Congress. Webster hinted later that he believed the president had not even read his memorandum, that his mind had been made up to use the veto again ever since he had read Botts’s coffeehouse letter. Webster knew how much the letter troubled Tyler from their conversation on the night of August 20, and he rightly characterized that missive as an attempt to “place him [Tyler] in a condition of embarrassment.” It worked.30

The House passed the Fiscal Corporation Bill—having rebranded it with the name Tyler preferred—by a vote of 125 to 94 on August 23. The next day it went to the Senate. On the twenty-fifth Tyler met with the cabinet for their regular Wednesday morning council and, according to Ewing, “seemed gloomy and depressed.” He also “intimated in strong terms that he would not sign the bill and earnestly requested us to get it postponed.” When the men informed him that it would not be easy to stop the course of the legislation, which was now in Senate committee, the president replied “that we had got it up easily” so “we might postpone it as easily if we chose to do it.”31

Webster, who characterized Tyler as “agitated and excited” during the cabinet meeting, agreed to speak to Whig senators to see if they could delay a vote on the bill. He viewed postponement as essential to keeping the Whig Party from falling apart.32 Ewing also made an effort to bring about a postponement but failed. Tyler, almost unhinged by now, continued to plead for a delay during the last week of August, “not,” Ewing said in recounting a comment the president had made, “because of the political but of the personal difficulties which immediate action upon it would involve.”33 Clearly, Tyler dreaded the prospect of having another bank bill before him, and he was putting tremendous pressure on his cabinet to work behind the scenes on his behalf. His behavior demonstrated that he would much rather put off making a difficult and unpopular decision—vetoing the bill—than confront it and get it over with. The John Tyler who had told his cabinet with such force on his first day in office in April that he would be responsible for his administration was nowhere to be found in August. Events had overwhelmed him.

Indeed, Tyler’s penchant for waffling and indecision was on full display for all of official Washington to see. By late August, the back and forth between the White House and Congress over the bank bill had become a farce worthy of Shakespeare, with Tyler playing the lead role. “The President is in a wonderful quandary,” one congressman wrote. “He is sometimes disposed to approve the new bank bill, and then violently opposed to it.” And then there was the matter of the cabinet. “He is sometimes tired of his cabinet & anxious that they should resign, then he is afraid of the storm that would attend their resignation & wishes them to hold on whilst . . . Wise & the locos are urging him to remove them.” All most observers could do was shake their heads.34

Leading Whigs were convinced that Tyler had decided to veto the latest bank bill should it pass and would welcome the opportunity to overhaul his cabinet. North Carolina senator Willie P. Mangum wrote that it was “believed by many that Tyler will prove a traitor to his party. I think he will be a Locofoco in three months from this time. His Cabinet will blow up, & Congress be in open war against him.” There was also a report that Duff Green was in Kentucky intriguing on behalf of the president, most likely without Tyler’s knowledge. In particular, it was said, Green sought to get on the good side of the Wickliffe family—bitter enemies of Henry Clay—and may have dangled a potential cabinet appointment before Charles A. Wickliffe, an anti-bank Whig who was sympathetic to Tyler’s predicament.35

Supporters of Clay in Washington told everyone who would listen that Tyler intended to dismiss the cabinet and thwart the Whig agenda. Tyler partisans—much smaller in number—maintained that Clay had seen to it that the cabinet would resign should he veto the bill, throwing the government into turmoil and perhaps leading to the resignation of the president himself. None of these rumors could be substantiated. The atmosphere was toxic, much more so than it had been in early August when Tyler was deciding whether to sign the original bank bill. The first veto had heightened tensions and created political theater the likes of which the capital had not seen since the days of Andrew Jackson.36

In nearby Baltimore, too, the impending Senate vote on the bank bill had caused a great deal of excitement. Upshur traveled to his in-laws’ home there in mid-August and reported to Professor Tucker that people could not stop talking about Tyler and Clay. Speculation was rampant over what the president would do if forced to make a decision on another bank bill. “If I may judge of the state of public opinion, by those expressions of it which I hear in this city,” Upshur told his friend, “there is no retreat for Tyler; he must stick or go through.” He professed to be “surprised at the strength & universality of the condemnation” the Whigs had heaped on Tyler. As usual, he bemoaned the lack of progress in creating a states’ rights party. The president and Congressman Wise, he declared, “appear to me to be absolutely odious, & neither of them could command ten votes among all their former admirers in this city.” Upshur repeated his criticism that the president “has not been decided enough” and worried that he had “evidently aimed rather to conciliate.”37

An attempt at conciliation was exactly what was on Attorney General Crittenden’s mind on the evening of Saturday, August 28. He and his wife hosted a party at their home in Washington for some one hundred guests that night, having invited the president and Senator Clay. Never one to turn down libations or an opportunity to socialize, Clay eagerly accepted the invitation and arrived in good spirits. Tyler failed to show up. Undeterred, several congressmen left the party and made their way to the White House, where they hoped to persuade the president to accompany them back to the Crittenden home. Surprisingly, given his recent state of mind, Tyler agreed. When he arrived, a nearly drunk Clay answered the door, welcomed the president, and immediately led him to the sideboard and offered to pour him a drink. Clay’s beverage of choice was Kentucky whiskey. “Well Mr. President what are you for?” he asked. Tyler looked confused. “Wine, Whiskey, Brandy or Champagne? Come show your hand.” According to one witness of the encounter, Tyler replied that he would take a drink of whiskey. After a few minutes of awkward conversation, he seemed to loosen up and told his hosts that he had come “for a frolick [sic].” At least the Crittendens had gotten Clay and Tyler together.38

Unfortunately, the party had little effect on the political situation in the capital. Tensions continued to escalate. For some, this was just fine. Wise, for example, could not wait for the Senate to pass the Fiscal Corporation Bill and had no doubt what the final outcome would be. “It will be pushed through, and will be vetoed,” he confidently informed Tucker; “Tyler is more firm than ever.” Wise also welcomed the dissolution of the cabinet that most observers believed was coming. “We are on the eve of a cabinet rupture,” he asserted. “With some of them we want to part friendly. We can part friendly with Webster by sending him to England. Let us, for God’s sake, get rid of him on the best terms we can.”39

Wise’s statement is revealing. By using the pronouns “we” and “us,” he indicated that he was playing a significant role in the Tyler White House (or at least thought he was). But he had a habit of exaggerating his own importance. At the very least, though, the Virginian had the president’s ear, and the two men shared many conversations about what Tyler’s course of action should be. No doubt, they had discussed a second veto and what would happen if the cabinet resigned. That Wise wanted to find a soft landing spot for Webster—minister to Britain—reflected his awareness that the secretary of state had done right by Tyler in the fight with the Whigs and was deserving of some loyalty on the part of the president.

To Tyler’s chagrin, the Fiscal Corporation Bill passed in the Senate on September 3 by a vote of 27 to 22. Debate over the measure was, to put it mildly, spirited. The Whigs would not back down; Rives was the sole Whig who voted against the bill. Democrats stood united against what the Missourian Benton derisively called the “corporosity.” The matter was in the hands of President Tyler yet again.40

Senate passage of the bill led each man in the cabinet to agonize over what to do in the likely event of another veto. In an effort to stave off crisis, both Ewing and Webster urged the president to sign the bill. James Lyons, Tyler’s friend from Richmond, also weighed in, writing to the president that he “trust[ed], therefore, for your sake and that of the country, that the bill will meet your approbation.” On September 4, the day after the Senate passed the measure, Tyler discussed his options with his cabinet. According to Ewing, the president “felt anxious and unhappy.” He indicated that he would probably veto the bill and floated the idea of accompanying his veto message with a “solemn declaration” that he would not be a candidate for president in 1844. Tyler “thought such declaration would place his motives fairly before the people and disarm those who were assailing him.”41

The offer to withdraw from the 1844 race, however, was insincere. Tyler had no intention of squandering an opportunity to be elected president in his own right. When the cabinet advised against including such a statement with his veto message, the idea was “very readily surrendered by the President.” In the course of the discussion on this matter, Tyler informed the cabinet that he had deleted a sentence from his inaugural address that disclaimed his desire for a second term. He had done so, he asserted, because he feared that the effect of such a statement “should be to turn the batteries of Mr. Clay and his friends on Mr. Webster.”

This was nonsense. Tyler’s motives in refusing to disavow a second term were purely personal and reflected his burning ambition to be elected in his own right, regardless of his claims of selflessness and disinterestedness. By framing his decision to delete the statement in the inaugural address as an attempt to shield Webster from political peril, Tyler was perhaps trying to manipulate the secretary of state into staying in the cabinet after he vetoed the Fiscal Corporation Bill. The president acknowledged to his cabinet that day that he “rallied no friends around him and had no party.”42 He would need influential allies as he attempted to build a viable political base for 1844. Evidently, in September 1841 he regarded Daniel Webster as a key component of that base. He most certainly did not view him through the same states’ rights prism as Wise, Upshur, and Tucker.

Tyler also informed his cabinet that he intended to issue a much harsher denunciation of the Fiscal Corporation Bill than what he had given Congress in his first veto, saying “he should criticize the bill with much severity.” Webster gently told the president that perhaps this was not the proper course to take. For their part, the other cabinet members were not yet ready to concede the veto and expressed their hopes that he might still find a way to sign the measure into law. Ewing, in particular, saw Webster’s influence as representing the best chance to persuade Tyler to go along with the bill and save their jobs. These hopes, however, were unrealistic, for all of them were aware of Tyler’s stance on local discounts.43

As with the veto of the first bank bill, Tyler did not immediately announce his judgment. He again seemed to be in no rush to make his decision public. Upshur, who had made the trip from Baltimore to Washington with the express purpose of persuading Tyler to veto the bill, told Tucker that he had given the president “a chart by which a blind man might have directed his course.” Upshur—as well as Wise and Tucker—were anxious for the veto and were frustrated with Tyler for again moving at a glacial pace. As always, Upshur feared the president was going to conciliate. From Richmond, Thomas Ritchie was more optimistic, writing that he hoped that Tyler would “prove himself worthy to the proud State to which we belong.” But if Tyler “knuckle[d] to aspirants and hotspurs,” such as Clay and Botts, “who are attempting to ‘head’ him then indeed, is his glory eclipsed, the reputation he has just won by his firmness will be gone, and his political days will be numbered.”44

Whig partisans who favored the Fiscal Corporation Bill were just as certain that Tyler would not conciliate. By now, it seemed everyone was watching the White House, waiting for the inevitable veto and wondering what it would mean for the fate of the special session. The toxicity of Washington had even spread to other parts of the country. Kentucky governor Robert Letcher reported to his friend Crittenden that he had “received a letter this morning [September 8], from a man in Russell county, asking me if I thought it would be an unpardonable sin to go to the city and kill him (Tyler).” This potential political vigilante, Letcher said, “wrote as if he thought he had a call to put him to death.” Apparently, too, letters arrived at the White House threatening Tyler with assassination. Handbills denouncing him were tacked up on lampposts. All of this, over a veto.45

One Sunday evening a messenger brought news of a disturbing rumor to the White House. “They have it through the city that I have been shot!” the president exclaimed to a guest with whom he had eaten dinner. “With paper bullets of the brain, I suppose they mean, Mr. President,” his visitor replied. Tyler shook his head. “No,” he said, “with leaden bullets from a pistol.” He then walked his guest out to the portico, where a crowd had gathered in an effort to determine if the rumor was true. According to one witness, the president seemed indifferent to the report and cared little for where it had originated. One of the men in the crowd made a comment expressing his belief that one could not be too careful with madmen walking the streets. Tyler replied that if someone dared to take a shot at him, “it will be more in malice than in madness.” With that, he told the group he needed his daily exercise, took leave of them, and proceeded to walk away, unattended and undaunted.46

Matters turned a bit more serious when an unmarked package mysteriously showed up one day in the White House entrance hall. The size of the package was suspicious: it was a good deal larger than most parcels, and the box was made of wood. The servants refused to open it, fearing that what they called an “infernal machine” might be inside. Americans had been shocked in 1835 upon learning of Giuseppe Marco Fieschi’s assassination attempt on King Louis-Philippe of France by using what the newspapers referred to as an “infernal machine.” Thus, the term and the idea of political murder were on everyone’s mind and left the White House in a near-hysterical grip of panic. Alerted by the commotion, President Tyler walked downstairs to where several members of the household had gathered. Nobody—including Tyler—wanted to open the wooden box.

The doorkeeper, Martin Renehan, was summoned. Tyler showed him the package and asked him what he thought. Renehan gave a cursory inspection and told the president that he had an idea. Disappearing, he returned a few moments later with a meat cleaver borrowed from the kitchen. “By the powers,” he said calmly, “I’ll chop it up in less than no time.” Tyler looked on, horrified, as the doorkeeper rolled up his sleeves, picked up the package, placed it on a table, and began hacking away at it. He succeeded in tearing the box apart. Reaching down and pulling its contents out, he held up a model of an iron stove for the president and the frightened servants to see. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief. Crisis averted, Tyler told Renehan that he should not tell anyone about the incident. “If you do,” he warned, “they’ll have me caricatured.” Renehan nodded. Nobody was told, at least not until the doorkeeper related the story in the 1860s.

By the time of this incident, Tyler feared for his own safety and for the safety of his family. He had been unnerved by the drunken mob that had appeared outside the White House in the early morning hours after his veto of the first bank bill. Such public access to his office made him a potential target. Moreover, the strange parcel underscored the very real danger of some harm befalling him or his family.

Renehan kept a gun in his room off the entrance hall, as had been the custom for several years, but Tyler wanted more protection. In early 1842 he would send a bill to Congress calling for an “auxiliary guard” comprising a captain and three men. After some bluster in the Senate that such a guard smacked of Caesarism, both houses passed the bill fairly easily. They thus created the first permanent White House security force—the precursor to the Secret Service, which would begin providing presidential protection after William McKinley’s assassination in 1901.47

![]()

On September 9 the wait was over. He had done it again: Tyler vetoed the Fiscal Corporation Bill. This time Robert Tyler delivered the message up to the Capitol. It was addressed to the House this time, since that body was where the current bill had originated. The House was in session—in the middle of debate, actually—when Robert arrived. He brought with him four bills that his father had signed into law, including one granting lifetime franking privileges for Anna Harrison. These new laws, however, would not lessen the blow of the veto for Whigs. Nor would they spare Robert’s father from the torrent of abuse that seemed sure to follow.48

Tyler had done his best to follow Webster’s advice and resisted the urge to unleash his fury on the Whigs, though the last month had surely tried his patience enough to make him want to vent his anger. In a fit of pique, however, he got a small measure of revenge by sending the message to the Madisonian to be printed rather than use the official printers of the House, Gales and Seaton.49

Tyler began the message by stating that it was with “extreme regret” that he had sent the veto message to the House, but he felt “constrained” by the duty to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution” and thus could not sanction the Fiscal Corporation Bill. He defended the right of a president to use the veto, chastised the Whigs for their sleight of hand in framing the bill so that promissory notes operated like bills of exchange (and thus could be discounted), and defended the South by proclaiming that the bank would primarily benefit the commercial Northeast. To his credit, Tyler concluded the message with praise for the legislative branch, saying that the House and Senate had “distinguished themselves at this extraordinary session by the performance of an immense mass of labor.” They had passed several beneficial laws. It had been Tyler’s “good fortune and pleasure to concur with them [Congress] in all measures except this.” He hoped for “time for deep and deliberate reflection on this the greatest difficulty of my Administration” and looked forward to the next session, when he hoped they could come together to find a suitable fiscal agent. He had made a commitment to the American people to try again.50

The last part of Tyler’s message, intended as an olive branch of sorts and designed to soften the blow of yet another bank veto, did little to make the Whigs feel good about the special session. To be sure, they had repealed the Independent Treasury, passed a $12 million bond issue to loan the government money, and won a uniform bankruptcy law that allowed debtors to initiate legal proceedings to relieve them of their financial burdens. They had secured passage of a modest new tariff, which kept duties at the 20-percent level mandated by the Compromise Tariff of 1833, and were able to push a new Land Act through Congress. All of these measures had received President Tyler’s signature. But, just as important, all were deeply flawed bills that bore the scars of Democratic amendments, sectional tensions within the Whig Party, and concessions by party leadership. The special session had been successful to some degree, but it had fallen far short of Clay’s expectations—and the second bank veto was the hardest blow of all. As it was with the first, the Whigs did not have the votes to override.51

“My friends,” Clay told the Whig caucus, “we have done our duty. We have maintained the true policy of the Government.” The Whigs had pursued their goals in good faith and with the good of the American people in mind. “Our policy has been arrested by an Executive that we brought into power,” the senator declared. “[Benedict] Arnold escaped to England, after his treason was detected. [John] Andre was executed. Tyler is on his way to the Democratic camp.” After all that had happened, this suited Clay just fine. “They may give him lodgings in some outhouse,” he sneered, “but they will never trust him. He will stand here, like Arnold in England, a monument of his own perfidy and disgrace.” Clay also scoffed at Tyler’s claim that he wanted to work with Congress at the next session to devise a suitable fiscal agency. The “wit of man,” he said in exasperation, “and [I] thought [I] had some, but not enough for the purpose—could not devise a plan that would meet the views of the President.”52

Most Whigs no doubt felt the same as Clay and judged the special session a monumental disappointment. Tyler’s second veto; the desire to end the session, which had dragged on for more than three months; and the late-summer Washington heat left many in Congress on edge. They were frazzled and wanted to go home. The toxic political atmosphere and the confrontation between President Tyler and the Whig majority had taken its toll.

Adding to the poison was Congressman Botts, who savagely criticized Tyler after the second veto and called the president’s integrity into question. In particular, Botts alleged that on a trip the two men had taken to western Virginia in the summer of 1839, he had heard Tyler say “that he was satisfied a bank of the United States was not only necessary, but indispensable; that the country could never get along without one, and that we should be compelled to resort to it.” He also claimed that during the 1840 campaign, during a speech in Marshall County, Virginia, Tyler had denounced Jackson for vetoing the bank recharter bill in 1832. Of course, both of these assertions made Tyler out to be a hypocrite. As with most statements Botts uttered, these were of questionable veracity, but they played well to Whigs in Congress.53

The president’s states’ rights friends were, of course, pleased with the veto. “Tyler was right in vetoing the Bank Bill,” South Carolinian Waddy Thompson told Tucker, for “he could not have signed it without subjecting himself to the charge of resorting to a subterfuge.” Thompson had been mostly outside of Tyler’s circle up to this point but was making his support of the president known to Tucker and Upshur, who were on the lookout for allies. At Tucker’s request, Tyler would soon name Thompson US minister to Mexico. Tyler in-law Major Washington Seawell was “glad to see” that the president “possess[ed] so much moral firmness.” Preston offered his support of the president on the floor of the Senate. Upshur applauded the veto message but still found fault. “Tyler needs much more counsel than he is willing to take,” he sniffed.54

Democrats also expressed their approval of Tyler’s course. They were downright giddy, in fact. Perhaps the most effusive in his praise in Washington was James Buchanan. He called the veto message “firm and determined in its spirit.” More importantly, he gushed, it “precluded all hope of the establishment of any National Bank, or corporation, with private stockholders, as long as John Tyler shall continue to be President of these United States.” The country, Buchanan proclaimed, would benefit from the veto. It would be “hailed with pleasure” all over the nation.55

Meanwhile, the members of the cabinet found themselves in the very position they had dreaded for nearly one month. On Saturday, September 11, all of them but Webster resigned. Tyler was pleased to retain his secretary of state, having enjoyed cordial relations with the man and appreciating his steady course of moderation in the cabinet. Tyler also well knew that in a battle with Clay for the supremacy of the Whig Party, it would be better to have Webster in his corner and in his cabinet.56 For his part, Webster liked the president and felt none of the ill will displayed by congressional Whigs.

![]()

Congress announced that it would adjourn on Monday, September 13, at 2:00 P.M. This meant that Tyler had less than forty-eight hours to compose a new cabinet and forward the men’s names to the Senate, where they could be confirmed. John Jr. believed this was a deliberate ploy on the part of the Whigs to stymie the Tyler administration. If his father could not receive Senate confirmation on his cabinet nominees before Congress adjourned, the entire government would be thrown into disarray. He feared the president’s resignation would follow.57

John Jr. was engaging in a bit of melodrama and had assigned motives to the Whig majority based on their treatment of his father over the veto. What seems more likely is that the special session had lasted long enough—too long for some—and the legislators wanted to return to their homes to get some rest before the second session of the Twenty-Seventh Congress began in December. Remember, this had been a special session. Usually, Congress did not meet during the summer months, partly a concession to the oppressive heat in the capital. Also, the Whigs believed they had accomplished all they could; staying longer served no purpose. That being said, more than a few Whigs had to have enjoyed the thought of causing trouble for Tyler.

Apparently, the president had been thinking about the men he wanted for at least two weeks and had conversations with Senator Rives on possible cabinet nominees. Tyler sent the names to the Senate on the morning of September 13.58

The men who joined Webster in the newly reconstituted cabinet were all Whigs. Tyler took special pleasure in this fact. “I know that it entered into the belief of all the conspirators,” he wrote his friend Tazewell, alluding to the Clay wing of the party, “that I could not surround myself with a Whig cabinet.” But he had. “I have, in my new organization,” Tyler informed him, “thrown myself upon those who were Jackson men in the beginning and who fell off from his administration for very much the same reasons which influenced you and I.” They were “men of acknowledged ability,” he said, “and conform to my opinions on the subject of a national Bank.” The president had stayed within his party, then, albeit with a few states’ rights selections, which gave the lie to the assertions of some Whigs that he only wanted to court favor with the Democrats. From Albany, powerbroker Thurlow Weed surveyed the new appointments and remarked, “John Tyler is a good Whig and intends to be hereafter.” The Washington National Intelligencer concurred with Weed, declaring that “the appointments are upon the whole better than could have been expected.”59

Tyler named fifty-five-year-old Walter Forward to the Treasury post. A former congressman, Forward was a native of Connecticut but had grown up in Pittsburgh, where he made a name for himself as a lawyer and newspaper editor. An enthusiastic supporter of the Harrison-Tyler ticket in 1840, he had been first comptroller of the Treasury, which made him a logical choice for Tyler’s new Treasury secretary. Forward was described by one Whig as “plain and affable.” The president no doubt appointed him because of his popularity in the party. He was an uncontroversial selection.60

Charles A. Wickliffe received the job of postmaster general. Wickliffe, fifty-three years of age, had recently been governor of Kentucky. A War of 1812 veteran, he and Tyler were friends. In fact, the two men had boarded together in Washington when they were young congressmen. Wickliffe was a sworn enemy of Clay, which must have appealed to Tyler. Also appealing was his friendly relationship with John C. Calhoun, which Tyler may have thought would come in handy at some point in the future.

The president offered John McLean of Illinois the position of secretary of war, which was a rather odd choice since McLean was an associate justice of the US Supreme Court, having been nominated by Jackson in 1829. But Webster wanted McLean. When he turned down the offer, the post went instead to fifty-three-year-old John Canfield Spencer, the secretary of state for New York. A graduate of Union College, Spencer had once served as private secretary to Governor Daniel D. Tompkins and practiced law in Canandaigua, the hometown of Francis Granger. He was a US congressman from 1817 to 1819 and became Speaker of the New York State Assembly in 1820. Spencer had once hosted Alexis de Tocqueville at his home when the famous chronicler of American democracy visited the United States in 1831, later writing the preface to the 1838 American edition of Democracy in America. Although now a man whom American historians have largely forgotten, Spencer was well known and well regarded in his day. More importantly, his appointment was Tyler’s attempt to court Weed and New York governor William H. Seward, two Whigs decidedly hostile to Clay’s ambitions.61

Hugh Swinton Legaré was Tyler’s choice for attorney general. Forty-four years old in 1841, Legaré was of Huguenot ancestry and a native of Charleston, South Carolina. An odd-looking man—a childhood illness had left him with a fully developed torso but shrunken extremities—he had attended South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina) and was well known throughout the South for having founded the Southern Review. Legaré had opposed his state’s nullification stance during Jackson’s presidency, had served one term in Congress, and more recently enjoyed a post in Brussels, where he served as US chargé d’affaires. A highly esteemed attorney, by 1841 he was also regarded as one of the South’s finest intellectuals, though some questioned his political ability. He believed slavery inhibited the economic development and modernization of his native region but could devise no satisfactory plan of emancipation. Tyler had met Legaré in 1819 when the two men shared a stagecoach trip to Fredericksburg, Virginia. He was instantly impressed with the younger man. “We were strangers to each other,” Tyler recalled many years later, “but who waits for an introduction in a stage-coach?” Since that evening Legaré had often spoken of the virtues of Jeffersonian republicanism. It was somewhat surprising that Tyler wanted him in the cabinet, though, because the South Carolinian had supported the national bank in the past. He was also warm friends with Senator Rives and an associate of Senator Preston, which may account for the appointment more than anything else.62

Finally, Tyler named Abel Upshur as his new secretary of the navy. He had been rumored to be the president’s choice for minister to London but told Tucker that he would have turned down the appointment if it had been offered. He was evidently surprised to be the president’s choice for the Navy Department and doubted whether he would have any influence. “You are entirely mistaken that he [Tyler] derives counsel from me,” Upshur informed Tucker. A more accurate statement was that Tyler did not derive all his counsel from Upshur, who no doubt hoped he could use his new vantage point to press for a new states’ rights party. In any case, his appointment meant that one of the Virginia intellectuals now had a direct conduit to President Tyler and a job working for the federal government.63

Almost inconceivably, the Whigs in the Senate gave Tyler very little trouble over his new cabinet appointments. Upshur faced the most opposition—five Whig senators voted against his confirmation—but the entire slate was confirmed by one o’clock on the afternoon of September 13. All of the talk about throwing the government into chaos had not come to pass. The new cabinet had now been formed as Congress adjourned. The president could begin preparing for the next session of Congress.64

But Tyler himself no longer had a place in the Whig Party. Shortly after Congress adjourned, a group of between fifty and seventy Whigs gathered in Capitol Square to publicize a manifesto that had been written by the novelist and Baltimore congressman John Pendleton Kennedy. The manifesto roundly criticized Tyler’s behavior, especially over the bank issue, and declared that the party could no longer “in any manner or degree” be “held responsible for his actions.” The Whigs declared their determination to rid the nation of executive usurpation and, among other remedies, suggested that a constitutional amendment curtail a president’s use of the veto. They referred to Tyler as “His Accidency,” displaying their resentment over how he had come to the presidency and how he had destroyed their agenda. Then, in ceremonial fashion, Tyler was formally read out of the party. He had been excommunicated. No president had ever been subjected to such ignominy.65

Tyler was certainly not happy to have been expelled from the Whig ranks. He may have been particularly disheartened that only three of the fifty-five southern members of the House of Representatives now publicly supported him. But he believed the vetoes that prompted his ouster had allowed him to preserve the integrity of his administration. Ironically, while he may have agonized over the political process of the special session and appeared weak and vacillating to some, in the end, his refusal to go along with the wishes of his cabinet and sign the second bank bill into law allowed him to safeguard the prerogatives of the executive branch. From this point on, Congress might not bend to his authority, but neither would he bend to its wishes. Tyler regained some of the confidence he had displayed on the day he assumed office.

But he was now a president without a party.

Greenway, the house in which John Tyler was born on March 29, 1790, and spent his childhood, was—and still is—located less than two miles from the north bank of the James River in Charles City County, Virginia. After Tyler’s father’s death in 1813, the house passed out of the family. Tyler bought it back in 1821 and lived there with his growing family until 1831, when he moved them to Gloucester Place. Carnegie Survey of the Architecture of the South, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

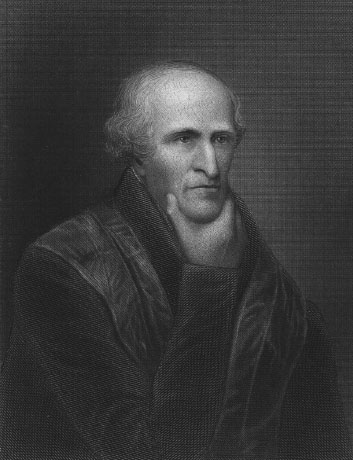

A highly respected attorney and jurist in Tidewater Virginia, John Tyler, Sr., was without question the single greatest influence on the future tenth president’s life. Loving yet firm with his children, the elder Tyler instilled in his son a devotion to public service and demonstrated the importance of honor in politics and domestic life. As an anti-federalist, the judge fought in vain to block Virginia’s ratification of the Constitution. When that failed, he adopted the ideology of strict construction and states’ rights, which became the guiding political principles of his son. Virginia Museum of History & Culture.

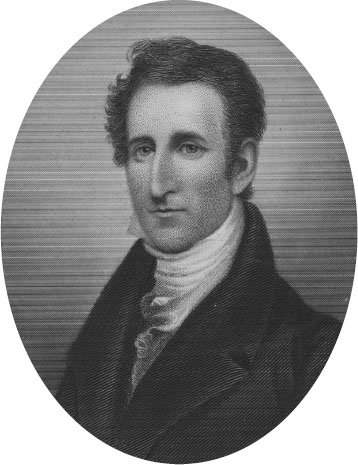

This engraving shows John Tyler in his mid-thirties, likely in 1826, when he was governor of Virginia. Proud of his service to the Old Dominion—which included three separate stints in the legislature—Tyler found more fulfillment as a national politician. Virginia Museum of History & Culture.

Known for her grace and beauty, Letitia Christian Tyler suffered from chronic ill health for most of her marriage to John Tyler. She gave birth to eight (possibly nine) children, and rarely accompanied her husband to Washington during his national political career in the House and Senate. The separation that defined her marriage to the future president took an immense toll on her both physically and emotionally. Afflicted by a stroke in 1839, she suffered another on September 10, 1842, which killed her, making her the first presidential spouse to die while her husband occupied the White House. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Robert Tyler, the oldest of the president’s sons (shown here after John Tyler’s death in 1862), helped manage the family farm while his father was in Washington serving in the Senate. Like his father and grandfather, Robert graduated from the College of William and Mary. After working for the federal government while his father was president, Robert became an attorney, settling with his family in Pennsylvania before the Civil War. Virginia Museum of History & Culture.

His family believed John, Jr., had all of the gifts that augured well for his success. Unfortunately, his aimlessness and lackluster academic career at William and Mary strained the relationship he shared with his father. Attempting to provide some structure, President Tyler made his son his personal secretary and paid his salary out of his own pocket. Alcoholism poisoned the young man’s marriage to Mattie Rochelle and at one point after he left the presidency, John Tyler feared for his son’s life. John Tyler, Jr., Papers, Special Collections Research Center, William and Mary Libraries, Williamsburg, Virginia.

Daughter of famed British Shakespearian actor Thomas Abthorpe Cooper, and herself a celebrated stage actress, Priscilla Cooper married Robert Tyler in 1839. Substituting for her ailing mother-in-law, she served as White House hostess from 1841 to 1844. After fainting at her first social event shortly after John Tyler assumed the presidency, Priscilla went on to become a much-admired and important part of her father-in-law’s administration. Virginia Museum of History & Culture.

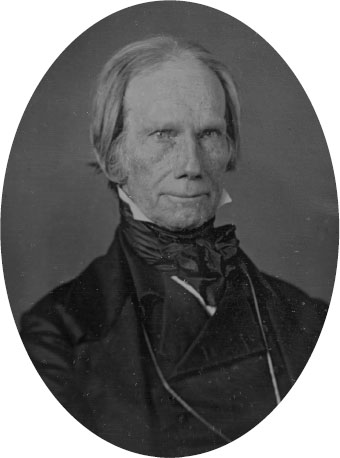

Mercurial and combative, Virginia congressman Henry Wise was a states’ rights Whig who became John Tyler’s most important confidant and political strategist while he served as president. Relishing the battle with Henry Clay and the majority of the congressional Whigs, Wise defended the embattled chief executive at every turn. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond.

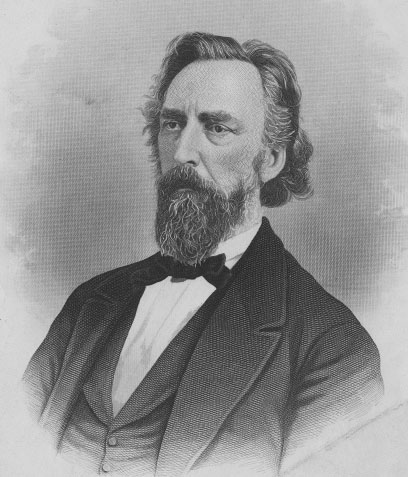

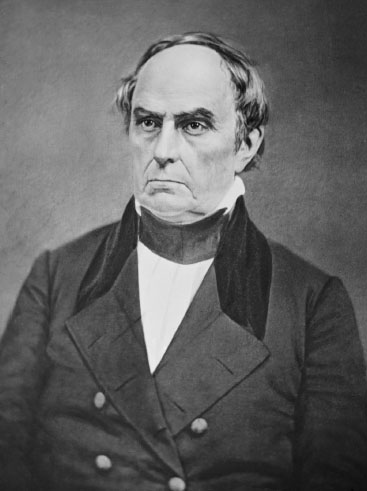

Representing Kentucky in the U.S. Senate after a long and distinguished career in national politics, Henry Clay was friendly toward John Tyler before the Virginian became president. During the special session of Congress in the summer of 1841 Clay became Tyler’s chief antagonist and political rival. The fight between Tyler and Clay—which both regarded as a matter of principle and which became overtly personal—understandably soured the men on one another, and they never reconciled. Tyler slightly softened his stance on his political enemy after Clay’s death. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

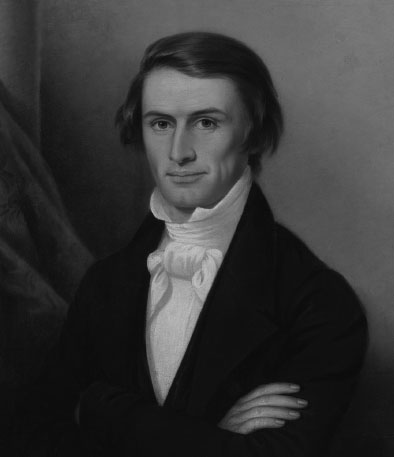

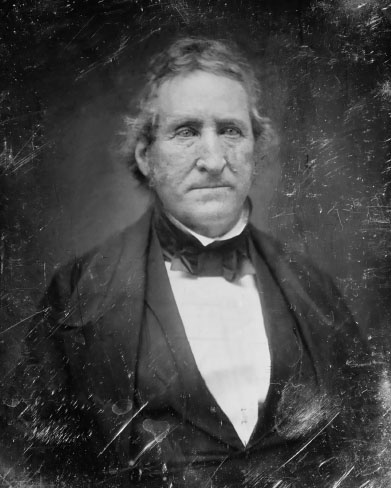

A giant in antebellum American politics and secretary of state in the Tyler administration from 1841–1843, Daniel Webster enjoyed Tyler’s company and the two collaborated successfully in the diplomacy that led to the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842. Webster was not afraid to speak frankly to President Tyler and left the administration in large part because he objected to Tyler’s pursuit of the annexation of Texas. Brady-Handy Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

A native of North Carolina and eventually a disciple of Andrew Jackson, Thomas Hart Benton rose to national prominence as a Democratic senator from Missouri. He seemed to take particular delight in antagonizing John Tyler when both men served in the U.S. Senate. Sarcastic and bombastic, Benton leveled especially harsh criticism of President Tyler, and relished the fight between the chief executive and the Whigs. Tyler never forgave Benton for the ill-treatment and denounced his nemesis for the rest of his life.

Undaunted by the thirty-year difference in their ages, John Tyler pursued the dazzling young socialite from Long Island with a vigor that shocked many Washington observers. Devastated by her father’s death on board the Princeton in February 1844, Julia Gardiner nevertheless agreed to marry Tyler soon after, becoming the first wife of a president to serve as first lady since Louisa Catherine Adams in 1829. She and Tyler had seven children together. White House Collection, White House Historical Association.