Michael Clarkson with his boys and Santa.

J. D. SALINGER (The Catcher in the Rye):

What really knocks me out is a book that, when you’re all done reading it, you wish the author that wrote it was a terrific friend of yours and you could call him up on the phone whenever you felt like.

Michael Clarkson with his boys and Santa.

MICHAEL CLARKSON: “A man is in Cornish. Amateur, perhaps, but sentimentally connected. The saddest—a tragic figure without a background. Needing a future as much as your past. Let me.” That was the note I wrote to J. D. Salinger. It took me two months to write it.

In 1978 J. D. Salinger was, to me, someone worth driving 450 miles to see. He was a missing father figure in my life, a soul mate, someone I wanted to go to Fenway Park with. I had to drive that 450 miles because there was someone in the world who felt the same pain that I did. My own father may have felt that pain, but he never talked to me. I had an emotional hole. I had no one to talk to. J. D. Salinger the writer and his fictional character Holden Caulfield thought like I did.

It was what he called, later, “a very cynical note.” However, it obviously worked because the next day, when we met, he mentioned the note.

PAUL ALEXANDER: There have been countless fans now for decades who have done this: they leave notes for him; they go up to his house unannounced; they knock on his front door.

MICHAEL CLARKSON: I wanted to meet that guy and pick his brain and sit down and say, “Do you know something? I had those problems when I was a teenager, and you’re the only guy who seems to understand.” Like Salinger and Holden, I went to private school. As I understood it, Salinger had a cold, distant relationship with his father. My father was an old Brit and shared nothing with me; if anything, he just put me down. Children are to be seen and not heard. I wanted to tell Salinger, “But you listen to me. You listened to me when I was a teenager. You listen to what children had to say.” My father didn’t listen to what I had to say. I didn’t cry when my father died. I had no one to pour out my feelings to. J. D. Salinger and Holden Caulfield thought like I did. By going to see Salinger, I felt he could help me. I didn’t necessarily want him to save me, to catch me at the bottom of the cliff. I was somewhat depressed, but I don’t think I was that delusional. I had two young children and I wanted to ask him, “Where do I go from here? What’s the next step?” I thought he could make some of the pain go away. At the same time, I had an emotional-spiritual crush on this writer.

During the 1950s and into the 1960s, Salinger spoke against the adult world. This voice coming out of the wilderness, challenging the adult world, was new to me. It was refreshing, and I was attracted to Holden Caulfield as a friend and pied piper. Salinger was the catcher in the rye. He was standing below the cliff and the children were falling off the cliff into the field of rye. That really struck a chord with me because the people I knew were failing as adults, becoming phonies, changing, not in a good way. They were giving up their love and their kindness for money and power. Salinger and Holden were the ones standing below that cliff. They were going to catch these kids and help them make that transition in a noble way, without having to compromise themselves too much.

I read a story about Salinger being a recluse; it made me even more attracted to him and his work. I felt I had to try to seek him out. I wanted to sit down and have a coffee with him. One day I said to my wife, “I’ve got to try it. I’ve got to go.” I kissed her goodbye, got in my car, and drove from Ontario to Windsor, Vermont, and tried to find Salinger, which was not easy, because the neighborhood people protected him. He’d lived there for some time, and they wouldn’t exactly tell me where he lived. I knew he was up on this mountain in a cabin somewhere at the end of a long driveway.

My plan was to pass a note to him through the clerk of a store where I knew Salinger picked up his newspapers every morning in Windsor, so I did. I had written this note, kind of a dramatic note, which I thought only he could react to. I needed to get his attention. The clerk in the store said, “I’ll pass it to him. He’s a nice man. He let me use his name as a reference for a job interview.”

I went to the Windsor Motel that night and hoped and prayed Salinger would pick up the note and come to the bottom of the driveway where I thought he lived and meet me the next morning. All night I was filled with apprehension, thinking if he didn’t show up I’d have to drive all the way back with nothing to show for it. The following morning, I went to the store, and, sure enough, he had accepted my note. Then I went to the area near the driveway—I wasn’t 100 percent sure I had the right place, but I thought I did—and waited in my car, hoping he would come. I was below this long, winding, gravel driveway. The house was at the top of the hill. I knew that he lived on top of a mountain—this wise man living in a cabin in the White Mountains.

I was waiting for probably thirty minutes, hoping that he would come out and speak to me, when I saw two cars coming down the driveway toward me. Matt Salinger, his teenage son, drove one car. Salinger drove the other, a BMW. His son drove on and Salinger’s BMW parked about ten yards away from mine. It may sound dramatic, but when he got out of that BMW in the middle of the forest, to me it was as if he stepped out of a dream. I’d had this dream for so long, an audience with J. D. Salinger. Unfortunately, that dream lasted maybe ten or fifteen more seconds, the time it took him to get from his car to my car.

Salinger had a regimented, military-style walk. He was elongated, with a quite distinguished look about him. He wore a sports jacket, and with his well-combed hair he seemed very Ivy League.

“Are you J. D. Salinger?” I said, because I didn’t recognize him from the photographs.

“Yes,” he said. “What can I do for you?”

I said to him very dramatically, “I was hoping you could tell me.”

He said, “Oh, come on, don’t start that kind of thing. Are you under psychiatric care?”

I told him I had left my job and driven all the way from Canada to see him. I told him I was not under psychiatric care and what I really needed was to be published. “You’re someone I could sit down and have a coffee with. It’s hard finding people I feel comfortable with. You think like I do.”

“How do you know I think like you do?”

“Because of your writing.”

I was calling him “Jerry” because he was so friendly. I was expecting a dramatic figure like Humphrey Bogart, and here was my Uncle Jarred. He was concerned about why I had come all this way. He was very friendly, but only to a point. Once he found out I was there because I thought he thought like I did and I wanted to talk to him about deep things, he got very frustrated. That really sparked something in him; his tone changed. He stepped back from my car and seemed to grow six inches; his face took on this long, drawn look.

“I’m a fiction writer!” he said. “It’s all fiction. There’s absolutely no autobiography in my stories. I can’t help these people. If I’d have known this was going to happen, I don’t think I would have started writing.” He stopped. “Do you have any other income besides your writing?”

I told him I was a reporter on the police beat, and at that point he got a little afraid I was going to do a story for the next day’s paper. “I’ve made my stand clear,” he said. “I’m a private person. Why can’t my life be my own? I never asked for this and I have done absolutely nothing to deserve it. I’ve had twenty-five years of this. I’m sick of it.” For the first time in my life I felt really hated and feared.

His delivery, timing, and flair superbly fit the message. It was like he was acting. He got in his car and dramatically left in a hail of pebbles and surprised me again—by elevating his gangling arm up through the open roof in a friendly wave.

As I sat there I felt that I’d blown it—my chance to talk intimately with J. D. Salinger. I sat in my car for probably another fifteen minutes, writing him another note. I was really sort of angry. It was almost like, “How dare you turn your back on us? We’re your fans. We’ve paid money for your books. You’ve gotten inside our heads.”

The second note I wrote to Salinger read, “Jerry: I’m sorry. It was probably a mistake coming to Cornish. You’re not as deep, as sentimental, as I had hoped. If someone had left his family and job and driven twelve hours to see me, I’d surely have given him more than five minutes. If I were after a story, do you think I would have told you I was a reporter? You say that you’re a fiction writer, but there’s more to it than that; you touch other people’s souls. The person who wrote those books I love.” I signed it. Then I added, “P.S. I’ll be staying at the Windsor Motel until morning.”

In the meantime Salinger returned in his car and came back up to me. “Haven’t you left yet?” he said. Then he threatened to have the authorities remove me from the premises.

“I was just going to actually pin this note up by your door,” I said.

“Well, come over here and give it to me.”

I got out of my car, walked over to his BMW, and gave him the note. He took a pair of reading glasses out of a case. He read the note. His face became long and drawn.

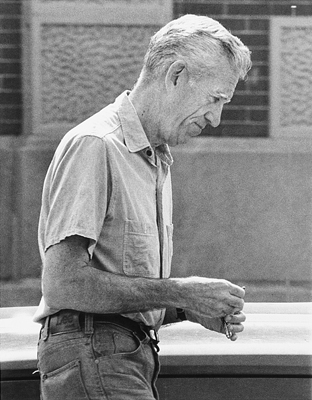

J. D. Salinger in 1979.

That seemed to defuse his frustration from earlier. “Well, I understand,” he said, “but I’m becoming embittered. I’ve gone through this scenario so many times in the last twenty-five years, I’m sick of it. Do you know how many times I’ve heard this story over and over again? People come from all over the place—from Canada, from Sacramento, from Europe. There was a woman from, I think, Switzerland who wanted to marry me. There was a guy in an elevator I had to run away from. There’s nothing I can tell these people to help them with their problems.”

He stopped. “Nothing one man can say can help another. Each must make his own way. For all you know, I’m just a father who has a son. You saw my son go down the road. I’m not here to help people like you with your problems. I’m not a teacher or a seer. I’m not a counselor. I, perhaps, pose questions about life in my stories, but I don’t pretend to know the answers. If you want to ask me a little bit about writing, I can say something. But I’m not a counselor; I’m a fiction writer.”

He went on: “I can’t give you a magic quarter that you can put under your pillow, and when you wake up in the morning, you’ll be a successful writer. Trying to teach somebody how to write is like the blind leading the blind. If you feel lonely, there are some therapeutic benefits in writing your way out of it. I would suggest reading a lot of other people. Don’t write facts. Blend in your own experiences. Plan your stories carefully. Don’t make rash decisions, and don’t get too hung up on the critics and all that psychoanalytic madness.”

We left amicably. I drove home to Canada. I didn’t want to do a story about my trip. I felt this was a very personal experience I had had.

—

MICHAEL CLARKSON: I started thinking, Salinger has never said the things he said to me publicly, and he’s never said these things to his fans, all these people who have come to see him like I did. He’s never given them, really, two cents. So the following year, 1979, I decided to do a story and went back to see him again. I wanted to ask him if he’d come out for a drink with me one night and we’d talk about the possibility of a story.

This time I went right up to his house. I stopped my car at the driveway where I’d seen him before, walked up the steep driveway, and what I found was almost a fortress. There was a garage I couldn’t get through, with dogs outside, and a cement tunnel that seemed to lead up to the house, so I went up there to the porch. There were glass doors; I looked inside for Salinger and thought, This is like a place Holden Caulfield would have built. It was a ranch-style house, a beautiful, Tyrolean structure, and yet inside, when I looked inside in the glass, it was quite a different world. It seemed like I was going back in time. It was depressing in a way: all these old photographs and hardwood floors, which seemed to be much older than the house, old National Geographics, and old movie reels. It seemed like he was trying to create an old-fashioned atmosphere.

There was a big screen on the wall. Obviously, he’d been watching old films, and there was Salinger himself, sitting on a chair; he seemed to be watching a portable TV and making notes to himself. I felt self-conscious, looking into his little world this way, but when I saw the photographs of his family all over the house, it almost made me feel better about him.

I was knocking on the glass. Salinger turned around and saw me. He looked kind of grumpy at me, like, “Who are you?” He came to the door with a German shepherd, then kicked out a two-by-four so he could release the glass door. He slid the door open and seemed a little puzzled. For one thing, I had a perm—I looked a little different than I did when I saw him the year before—but then he recognized me.

“I remember you,” he said. “You look quite a bit better than you did last time.”

“Yeah,” I said, “I’m feeling better.” I thanked him for helping me get into a better frame of mind than I had been in before.

“Are you still reporting?” he said.

“Yes.”

“You know,” he said, “I think the last time, in a way, you tried to bully me a little bit. I thought you tried to use me for the betterment of your career. Really, the only advice I can give you about writing is, Be yourself. Don’t make rash decisions. Plan your work carefully. Don’t listen to the critics and all that madness. At the end of the day, you’re in your own stew.”

I felt good about that and said, “Jerry, I wouldn’t have bothered you—I wouldn’t have barged in like this—if you’d answered my letters.”

“Oh,” he said, “maybe they were in with all the other stuff. I don’t know. I don’t remember seeing a letter from you. If so, I’m sorry.” He repeated what he had said a year before: he was just a fiction writer; he wasn’t there to help people like me; he was just a father who had a son.

On this second visit, Salinger looked a little older. There was more worry etched in his face. He wore jeans and a T-shirt and seemed quite frail, but his demeanor was about the same. He reiterated his advice: Just be yourself and don’t worry too much about the critics.

“Don’t you feel you have some obligation to your fans?” I said. “I’d like to do a story down the road, maybe give your side of it. You’ve never really spoken to your fans.”

He went into a bit of a rant, just like he did the first time I saw him. “I can’t be held responsible,” he said. “There are no legal obligations. I have nothing to answer for. I have no obligations beyond my writing. You’re just another guy who comes up here like all the rest and wants answers and I have no answers.”

“You’ve hidden from your fans and stopped publishing.”

“Being a public writer interferes with my right to a private life. I write for myself.”

“Don’t you want to share your feelings on paper with people?” I said.

“No,” he said. I remember him pointing his finger at me like a gun. “That’s where writers get in trouble.” He said he had regrets about his writing career. He called writing “the insanest profession.” He thought critics overanalyzed his work.

I asked him if he wanted to go out and have a drink.

He got agitated and said, “Thanks, but no. I’m busy these days.”

At that I left him—walked off, climbed down the hill, got into my car, and drove back to Canada.

I wrote a four-thousand-word piece about my two encounters with J. D. Salinger for the New York Times syndicate, which distributed it to media outlets throughout North America. I felt I had some sort of obligation to people like me, the fans who had come and had the door slammed in their faces. The article came out about a year and a half after I first met Salinger in 1978. Later on, People magazine did a story about my visits with Salinger. I think they tried to interview him about me, but I never did hear back directly.

I saw him outside the Windsor post office once, and he looked very fragile. He looked like he had only enough air to get back to Cornish, back to his house; he started to stumble to his car and was very wary of people on the street. I think he got a lot of mail, which he did not respond to, and in that way, I think, the Windsor post office was a dead letter office.