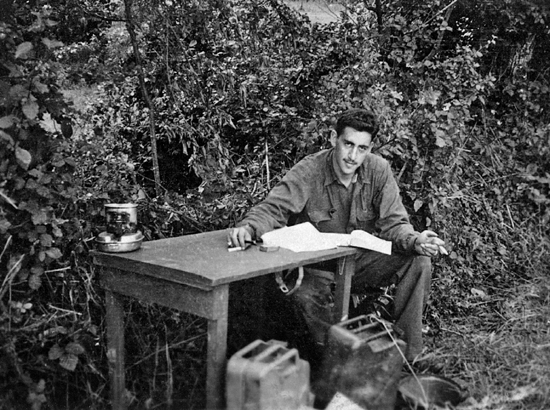

Salinger and two of the other “Four Musketeers”: John Keenan and Jack Altaras.

Along with the three other members of his unit of the Counter Intelligence Corps—Jack Altaras, John Keenan, and Paul Fitzgerald, the self-dubbed “Four Musketeers”—Salinger interrogates Nazis and civilians. Amid the bloodshed of the war, Salinger, whose job is to imagine what the enemy is doing and thinking, is furiously writing fiction. He undertakes his own private mission in liberated Paris: to find Hemingway, who also believes in producing copy under emotional and physical danger.

Salinger and two of the other “Four Musketeers”: John Keenan and Jack Altaras.

ALEX KERSHAW: Salinger played a very important role; anybody who had anything to do with intelligence in the Second World War played an important role. GIs, young guys in squads being asked to attack a village 150 yards away, wanted to know every single thing they could possibly know about that village: where machine-gun nests were, where the alleyways were, where the avenues of fire were. The job of men like Salinger was to provide information that would keep more of those guys alive.

The most important principle of combat is to know your enemy’s weaknesses and strengths. Unless you know that, you don’t know what you’re facing. Salinger’s job was to uncover information that would keep American soldiers alive by letting them know where they were going to be fighting and what they were up against.

LEILA HADLEY LUCE: The few photos I have seen of Jerry over the years are always clandestine-type photos. He is hidden somehow. These photos offer a glimpse at how private Jerry was. He was extremely private about his past and what he did. More than private: secretive. And I gathered that this was because of the war. Because he was in counterintelligence.

JOHN McMANUS: Counterintelligence units tended to be fairly shadowy at the division level. You’d have small teams operating out of either divisional or regimental battalion groups. They had quite a bit of freedom to move around an area of operations. Some concentrated on interrogating German prisoners to gain intelligence; others focused on the local civilian populations. Salinger did both. They operated at the cutting edge, working closely with rifle companies. They had interesting personalities, such as guys who were German-born speakers, emigrants to the United States because of the Nazi takeover of their country, and now they were back interrogating their countrymen. There were also French majors, people with linguistic skills that were useful in Europe. They melded together with what I call the I & R types, the intelligence and reconnaissance guys who’re trained to gather intelligence and observe. They were almost always enlisted soldiers doing the field intelligence work. It gets glossed over, but it was some of the most important work of World War II. They were trained to not be prominent; they were supposed to be in the shadows, which is where they remain in history. The U.S. Army tended to underemphasize intelligence. Intelligence officers were thought less of than, say, field engineers or operations types. This led to abysmal intelligence failures such as the Battle of the Bulge, which American command had no clue was on their doorstep.

Counterintelligence required strong interrogation skills. It could mean the bad cop, a heavy-handed, German-speaking GI telling a prisoner, “I’ve got guys who want to shoot you. Heck, I may shoot you myself if you don’t tell me where your unit is.” It wasn’t so much physical interrogation as mind games. It was the threat of shooting a POW out back. Sometimes it could be the light approach, the good cop, sitting down and establishing a rapport with the prisoner, giving him some food, talking about where his family’s from, and here’s a cigarette, leading into “Tell me what you know.” Counterintelligence officers like Salinger were trained to identify the weak link, the guy most likely to talk in a group of prisoners, and then break them.

IB MELCHIOR: As was standard operating procedure, immediately upon occupying the town, we ordered the population to turn in all cameras and binoculars. This was to prevent the locals from taking pictures of our equipment, buildings occupied by U.S. forces, signposts showing different units, and other subjects that might be helpful to the enemy. . . . These items were collected in large bins, often bathtubs from bombed-out houses; gasoline was poured over them, and they were destroyed.

Our standard procedure in locating suitable accommodations for the team’s use was to select an undamaged house that was still occupied by the Germans. We would order the occupants to get out within fifteen minutes, taking nothing but essential belongings, and leaving everything in the house—every door, every drawer, every cupboard—unlocked. As soon as the Germans were out, we’d move in. There was an excellent reason for doing it that way. . . . If you moved into a house, or any building, that was empty, it was liable to be booby-trapped. Favorite spots to place these devious, deadly devices were the bed, the toilet seat, an empty chair, the stove, or a picture of Adolf Hitler on the wall—in that order. Many a GI had blown himself up by flinging himself on a bed or plopping into an easy chair, by using a comfortable toilet seat rather than a slit trench in the cold outside, by trying to get warm at a friendly-looking stove, or by showing his contempt for the Führer by knocking his picture off the wall.

Usually Germans would comply with our order, however sullenly and resentfully. But not always. Some would weep and plead; others seemed too frightened to move on and had to be prodded on their way. . . . One of the teams in our detachment heard two shots when they came to take over a residential house. They immediately took cover, but when no other activity was heard, they entered the house to find a man and his wife had committed joint suicide rather than submit to American demands.

How do you get a man who is unwilling to talk to give you information of a nature obviously destructive to his own side? . . . If the prisoner persisted in his refusal to talk, [intelligence officer Leo] Handel would appear increasingly angry and sharp with his subject. If the man still refused to talk, step two would go into effect. Handel would order his sergeant to grab the prisoner and follow him. He would lead [him] out behind the house or a nearby shed. Here he would grimly draw a rectangle in the dirt the size of a man laid out, six feet by two feet. He’d throw a spade at the PW [prisoner of war] and order him to start digging. A few minutes of working on this cheerful excavation, and contemplating its probable use, as often as not made the PW quite talkative.

Should . . . the trench take shape with no signs of the PW caving in . . . Handel would turn to his sergeant in disgust and say in German, “All right, he’s almost finished. I’ll get the leader of that band of partisans who’s been begging us for a Kraut. They’ll take over. I’ll be in the interrogation room. You know I can’t stomach to watch.” And he then turned on his heel to walk away. Death might hold no terrors for the PW, but the prospect of death at the hands of a vengeful band of partisans was usually too much to face. . . . The PW would talk.

JOHN FITZGERALD: There was a bond between my father [Paul Fitzgerald], Jack Altaras, John Keenan, and J. D. Salinger. They served in the CIC together, and my father was the best man at Salinger’s first wedding. My father and Salinger stayed in close contact after the war and corresponded for nearly sixty-five years. My dad used to comment that during the war Altaras and Keenan would say, “There was really no time for us to do anything because we always had to stop for Salinger to sit by the roadside, working on short stories or his novel.”

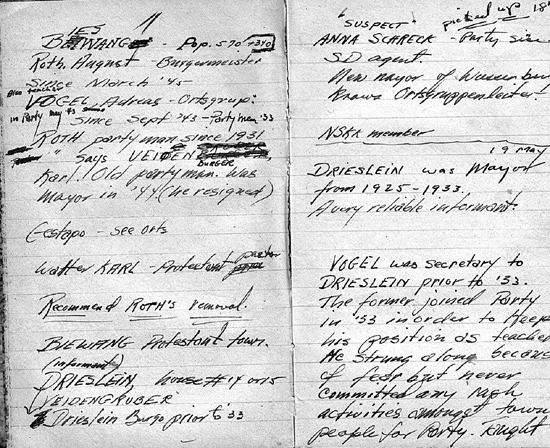

The only photo taken during World War II of Salinger writing The Catcher in the Rye.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Paul Fitzgerald, February 10, 1979:

You may be “baldheaded and slightly paunched”—that is, I’ll take your word for it—but who’s to say that image of you is any less real than the permanent one in my mind’s eye in which we’re all 1944 types, young guys in our early twenties. I saw John Keenan recently, yes, and spent a long, nice evening with him and Sally and their two grown daughters, and though he was gray and lined, too, and had put on a little weight, the 1944–’45 image of him is the fixed one in my mind, the permanent one. Will always see you with your helmet on, straps dangling. Altaras the same.

SHANE SALERNO: Over the past nine years, while working on this project, we have seen a lot of World War II material, but few items are as evocative as the diary Salinger’s fellow CIC agent and friend Paul Fitzgerald kept. The paper was so brittle that I had to take extra care when turning the pages so as not to pull them from the book. Fitzgerald wrote down the names of Germans he and Salinger arrested and the extent of their involvement in the Nazi Party: “Party man since 1933,” “Party cashier,” “Political leader,” “Rabid Nazi,” “Very rabid Nazi.” Buried in Fitzgerald’s diary among other addresses is the following entry:

Jerome D. Salinger

1133 Park Avenue

NYC, NY

Sacramento 2-7544

Page from Paul Fitzgerald’s World War II diary.

EBERHARD ALSEN: Even though a girl the narrator had fallen in love with in “A Girl I Knew” and her whole family were murdered by the Nazis, the narrator never expresses outrage against the Germans, nor does he make any statements to the effect that the war was a fight against pure evil. Salinger goes remarkably easy on German soldiers who appear in the story. He would later tell his daughter, Margaret, that anybody—for instance, the clerk at the post office—could turn out to be a Nazi. He implied that if you go looking for evil it is readily found, though probably disguised.

—

ALEX KERSHAW: Salinger witnessed the most beautiful day in history, according to many: the liberation of Paris, August 25, 1944.

MARK HOWLAND: I took five students to Princeton. They wanted to see what they could find, what they could discover of Salinger at the Princeton library. After we got into the reading room, we turned the last page of something and came across a three-by-five-inch light green page from a spiral notebook. And it was handwritten by Salinger, about the Allies coming into Paris. He talked about driving in the jeeps into Paris and Parisians holding their babies up for the Americans to kiss. He said that you could stand on the hood of your jeep and take a leak on it and it wouldn’t matter; it would be okay. He said anything you did would be fine.

SERGEANT RALPH G. MARTIN: As long as I live I don’t guess I’ll ever see a parade like that. Most of us slept in pup tents in Bois de Boulogne the night before, and it rained like hell and we were pretty dirty, so they picked out the cleanest guys to stand up in front and on the outside. I had a bright new shiny patch, so they put me on the outside. It was a good place to be too, because every guy marching on the outside had at least one girl on his arm kissing him and hugging him.

We were marching twenty-four abreast right down Champs-Elysées and we had a helluva time trying to march, because the whole street was jammed with people laughing and yelling and crying and singing. They were throwing flowers at us and bringing us big bottles of wine.

The first regiment never did get through. The crowd just gobbled them up. They just broke in and grabbed the guys and lifted some of them on their shoulders and carried them into cafés and bars and their homes and wouldn’t let them go. I hear it was a helluva job trying to round them all up later.

JOHN WORTHMAN: The people cheered and laughed and cried and wanted to embrace us, give us a drink, feed us newly ripe tomatoes . . . and just try to believe that we were really there and the Germans gone. I kissed babies, children, young women, old women, and women in between.

DAVID RODERICK: We rode into Paris in two-and-a-half-ton trucks. The reception we received has been a lifelong memory. People crowded in the streets, clapping and yelling, shaking our hands, passing out wine.

SHANE SALERNO: Amid the celebration, Salinger and John Keenan arrested a suspected collaborator, but the crowd beat him to death before the two CIC agents could take him in.

JOHN C. UNRUE: One of the great stories of literary history is the meeting of Ernest Hemingway and J. D. Salinger in Paris.

SEÁN HEMINGWAY: My grandfather was staying at the Ritz and receiving all kinds of visitors.

CARLOS BAKER: Another of Ernest’s visitors at this time was a young, dark-haired sergeant in a CIC outfit. His name was Jerome D. Salinger and he was much impressed with his first sight of Hemingway. Salinger was a writer of short stories, twenty years Ernest’s junior. At twenty-five he had already sold some of his work to Story magazine and the Saturday Evening Post.

LEILA HADLEY LUCE: Hemingway was Salinger’s icon; he loved the way Hemingway wrote. At the hotel, he went up to Hemingway and told him of his admiration for his work.

CARLOS BAKER: He found Hemingway both friendly and generous, not at all impressed by his own eminence, and “soft”—as opposed to the hardness and toughness which some of his writing suggested. They got on very well, and Ernest volunteered to look at some of his work.

LEILA HADLEY LUCE: Jerry asked Hemingway to look at a manuscript, which took a great deal of derring-do on his part, really. And Jerry was not somebody who would easily go up to someone and ask him to do anything for him.

SEÁN HEMINGWAY: Salinger had with him a copy of the Saturday Evening Post that contained a short story he had written, “Last Day of the Last Furlough,” which was about World War II. My grandfather was impressed with Salinger as a young soldier, and he was equally impressed with his writing. Upon meeting him, my grandfather told Salinger he had heard of him before, had read the story, and was delighted with it.

J. D. SALINGER (“Last Day of the Last Furlough,” Saturday Evening Post, July 15, 1944):

Vincent smiled. “It’s good to see you, Babe. Thanks for asking me. GIs—especially GIs who are friends—belong together these days. It’s no good being with civilians any more. They don’t know what we know and we’re no longer used to what they know. It doesn’t work out so hot.”

SEÁN HEMINGWAY: My grandfather was very much in tune with the price that infantry pay in battle. And I think that would have been kind of a romantic vision on my grandfather’s part—for my grandfather to see in Salinger, a talented young writer, fighting in the infantry, during World War II.

EBERHARD ALSEN: It’s reported that Hemingway said to someone, “Jesus, he has a helluva talent.” I’m sure it got around to Salinger, and that must have pleased him very much.

JOHN C. UNRUE: To Salinger, it was a meaningful endorsement that Hemingway would actually say Salinger had a “helluva talent.”

CARLOS BAKER: Salinger returned to his unit in a state of mild exaltation.

BRADLEY R. McDUFFIE: In her memoir Running with the Bulls, Valerie Hemingway, who worked as Hemingway’s secretary and later became his posthumous daughter-in-law, writes, “The contemporary American authors Hemingway most admired were J. D. Salinger, Carson McCullers and Truman Capote.” Hemingway also bought Valerie a copy of The Catcher in the Rye shortly after they first met in Spain in 1959. And a copy of the novel rests in Hemingway’s library at his home outside Havana, Cuba, a volume that is rumored to be autographed.

PAUL ALEXANDER: For his part, after meeting Hemingway, Salinger wrote in a letter to a friend that the “Farewell to Arms man” was “modest” and “not big shotty,” which, Salinger said, made him appealing.

LEILA HADLEY LUCE: They stayed in touch, and Hemingway told Jerry how much he liked his writing. Jerry was thrilled. He told me about this incident, how much it had meant to him, because he thought that Hemingway was the greatest writer.

LILLIAN ROSS: He shared with me a copy of the “Dear Jerry” letter Hemingway wrote to him when they were both serving in the second world war—a handwritten letter commenting on unpublished stories Salinger, who was then an unknown young beginner, sent him. “First you have a marvelous ear and you write tenderly and lovingly without getting wet,” Hemingway wrote. He added that he hoped he “didn’t sound like an easy praiser” and “how happy it makes me to read the stories and what a god damned fine writer I think you are.”

SEÁN HEMINGWAY: My grandfather thought of himself very much as a member of the 4th Division. He was assigned to the 22nd Regiment; Salinger was in the 12th. The 4th Division was known as the Ivy Leaf. My grandfather liked to refer to it as the Four-Leaf Clover; he believed a great deal in luck—whether you had it or you didn’t.

A. E. HOTCHNER: Hemingway was regarded as Tolstoy was in Russia, as a chronicler of war, a writer, soldier, adventurer, and as somebody who was bulletproof. He was immortal. He was going to live through the wars and through all the hard times. The most glamorous women in the world—Marlene Dietrich, Ingrid Bergman, Ava Gardner—surrounded him. A confluence of all these factors fed the imagination of the American public.

Hemingway’s personality aided and abetted his reputation as a writer. He had invested his writing with the style of his actual living. There’s no doubt his experience in the Spanish Civil War contributed mightily to For Whom the Bell Tolls, which was published in 1940 and was a tremendous bestseller, then a huge success as a movie. Not only did Hemingway receive publicity from where he went and what he wrote, but everything he did was exaggerated. The gossip columns in New York, when he visited there, would have him doing things he didn’t really do.

J. D. SALINGER: All writers—no matter how many lions they shoot, no matter how many rebellions they actively support—go to their graves half–Oliver Twist and half–Mary, Mary Quite Contrary.

SEÁN HEMINGWAY: Later, my grandfather is reported to have visited Salinger’s regiment. He got into a conversation with Salinger about firearms and which was better, the German Luger or the U.S. Colt .45. My grandfather, according to later accounts, said he believed the Luger was much better, and to make his point, drew the Luger and shot the head off a nearby chicken. Salinger was taken aback.

EBERHARD ALSEN: Now I tend to believe the story because in “For Esmé—with Love and Squalor,” Corporal Clay, the protagonist’s driver, shoots a cat. Sergeant X, the protagonist, is disgusted with him. I imagine Salinger was probably just as disgusted with Hemingway for shooting the head off that chicken.

J. D. SALINGER (“For Esmé—with Love and Squalor,” The New Yorker, April 8, 1950):

X threaded his fingers, once, through his dirty hair, then shielded his eyes against the light again. “You weren’t insane. You were simply doing your duty. You killed that pussycat in as manly a way as anybody could’ve, under the circumstances.”

Clay looked at him suspiciously. “What the hell are you talkin’ about?”

“That cat was a spy. You had to take a pot shot at it. It was a very clever German midget dressed up in a cheap fur coat. So there was absolutely nothing brutal, or cruel, or dirty, or even—”

“God damn it!” Clay said, his lips thinned. “Can’t you ever be sincere?”

SEÁN HEMINGWAY: I have to say the story sounds apocryphal to me. It plays up a sensitive image of Salinger and a macho image of my grandfather. Shooting the head off a chicken is a lot more difficult than it sounds. In the midst of the horrors that were around them in the war, it seems almost absurd.

BRADLEY R. McDUFFIE: In the years that followed, almost every Salinger critic has reported some version of this story. Unfortunately, the myth has led scholars to ignore the fact that meeting Hemingway during World War II is the most overlooked event in Salinger’s formation as a writer. Considering the meeting involves two of the most influential writers of the twentieth century, the oversight is difficult to comprehend.

A. SCOTT BERG: Hemingway had a huge influence on Salinger, and I’m thinking mostly of the style of writing here. Hemingway prided himself on writing according to what he called the iceberg theory. In this theory, as Hemingway first explained in Death in the Afternoon, and then in several other interviews and books, he says that if a writer knows enough about what he’s writing about, he can omit certain things in the story, and in fact, every time he omits something he strengthens the story. He likened that to the iceberg in which seven-eighths of it is underwater and all you see is the tip. Every time you leave something out, he said, it strengthens the iceberg from below and it affords the reader an even greater reading experience, because [the reader] is basically running the story, doing the film in his own imagination.

There was a corollary as well. Hemingway said if a writer does omit something because he hasn’t thought it through, the reader will instantly pick up on that and there will be a huge hole in the story.

Salinger is one of the prime exemplars of the iceberg theory of writing. He did it extremely well. His stories have a spare quality, and every word feels hand-selected.

GORE VIDAL: Hemingway was very good at graphic descriptions of violence and hunting. He was very good at showing how things happen: how you load your gun, how you sight it against the arc the bird is taking, how you fire. He was just very good at that. And there are people, the same people who read Popular Mechanics, who love that kind of writing.

A. SCOTT BERG: Hemingway, it has long been thought, had a greater influence on American writing of the twentieth century than anyone else because he introduced a new style, a new sound people read first in the short stories, but especially in The Sun Also Rises. This new kind of hard-hammered writing really took hold. Hemingway has had more imitators, more bad imitators, than any other writer of the twentieth century. I’m not suggesting that Salinger imitated him exactly, but I think Salinger got from him a rhythm and certain techniques.

DAVID HUDDLE: Salinger admired Hemingway’s front-line productivity, the ability to generate pages daily under any circumstance: it justified the term “professional.” Salinger wrote interior prose, quite different from Papa’s plain-spoken machismo style. Salinger wasn’t famous yet, but he could already match Hemingway in his discipline, pounding away on the typewriter even while Nazis attacked.

J. D. SALINGER (contributor’s note to Story, November–December 1944):

I’m twenty-five, was born in New York, am now in Germany with the Army. I used to go pretty steady with the big city, but I find that my memory is slipping since I’ve been in the Army. Have forgotten bars and streets and buses and faces; am more inclined, in retrospect, to get my New York out of the American Indian Room of the Museum of Natural History, where I used to drop my marbles all over the floor. . . . Am still writing whenever I can find the time and an unoccupied foxhole.

JOHN C. UNRUE: Salinger is reported to have continued writing, not with indifference to the casualties, but with a very great focus on his art—gotten under a table to write during times of attacks because he was intent on finishing something, or perhaps starting something.

DAVID SHIELDS: Salinger took his typewriter on his jeep and would sit in a foxhole and just pound away. Werner Kleeman would watch Salinger write his stories and voraciously read the magazines his mother mailed to him. The two men, both in their mid-twenties, would walk up the hill to the mess hall together. The duo went out on the same boat for training maneuvers and were frequently in “tough spots” surrounded by German artillery fire, Kleeman later told a journalist.

WERNER KLEEMAN: In those days, he was very normal, except that he would never let anybody read his letters home and always forged the signature of a censoring officer.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Elizabeth Murray, August 1944:

I can’t remember very acutely what happened in the early weeks. I can remember lying in ditches, face in the dirt, trying to get the maximum protection out of me hat. Stuff like that. But I can’t remember the intensity of the early frights and panics. And that’s nice.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Frances Glassmoyer, August 9, 1944:

I met and have had a couple of long talks with Ernest Hemingway. He’s extremely nice and completely unpatriotic. Sitting in my jeep as I write this. Chickens and pigs are walking around in an unbelievably uninteresting manner.

I dig my fox-holes down to a cowardly depth. Am scared stiff constantly and can’t remember ever having been a civilian.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Whit Burnett:

You never saw six-feet-two of muscle and typewriter ribbon get out of a jeep and into a ditch as fast as this baby can. And I don’t get out until they start bulldozing an airfield over me.

SHANE SALERNO: Diving out of a jeep under sniper fire, Salinger broke his nose and never got it fixed.

—

DAVID SHIELDS: Salinger needed war, the experience of war, to become a better writer, and he was becoming a more substantial and more serious writer, almost literally story by story. It was all one big bloody mess in his mind and psyche—the war and the writing and the surviving and the survivor’s guilt and the artist’s guilt and the ecstasy of artistic creation. He was a twenty-five-year-old ghost, looking for rebirth, placing stamps on envelopes sent stateside. Writing about the war was the only way for Salinger to survive the war. He was seeking oblivion, but he was also seeking fame.

Everything changes after D-Day; what Salinger pretended to know before he now knows viscerally and conveys with increasing emotional power. He’s learning to aim the gun at himself.

In late 1944, his OCS rejection still stings. In “Once a Week Won’t Kill You,” a soldier’s wife says to him, “I wish you’d phone that man with the thing on his face. The Colonel. In Intelligence and all. I mean you speak French and German and all. He certainly could get you at least a commission. I mean you know how miserable you’ll be just being a private or something. I mean you hate to talk to people and everything.”

“A Boy in France,” which was published in March 1945, is no longer merely entertainment; this is writing. After a “long, rotten afternoon” of combat, Babe Gladwaller finds a blood-soaked foxhole and tries to go to sleep but is close to shell shock: “I’ll open the window, I’ll let in a nice, quiet girl—not Frances, not anyone I’ve ever known—and I’ll bolt the door. I’ll ask her to walk a little bit in the room by herself, and I’ll look at her American ankles, and I’ll bolt the door. I’ll ask her to read some Emily Dickinson to me—that one about being chartless—and I’ll ask her to read some William Blake to me—that one about the little lamb that made thee—and I’ll bolt the door. She’ll have an American voice, and she won’t ask me if I have any chewing gum or bonbons, and I’ll bolt the door.” When U.S. soldiers in Vietnam saw death in its starkest form, they would often say, “There it is.” For Salinger, there it is.

Regarding “Elaine,” which was published just after “A Boy in France,” Salinger wrote to Burnett that it was about “the beginning of the end of beauty; and that’s where the war starts, I guess.” The prewar, Stork Club, wise-guy Salinger is now MIA. In “This Sandwich Has No Mayonnaise,” Salinger’s and Holden’s bodies are missing, breaking down, going silent: “Drenched to the bone, the bone of loneliness, the bone of silence, we plod back to the truck. Where are you Holden? Never mind the missing stuff. Stop playing around. Show up. Show up somewhere. Hear me? It’s simply because I remember everything. I can’t forget anything that’s good, that’s why.”

Which is the precise pivot to the postwar art lesson Salinger will spend his life trying to teach himself and the world. In “The Stranger,” published in December 1945, “With her feet together she made the little jump from the curb to the street surface, then back again. Why was it such a beautiful thing to see? . . . A fat apartment-house doorman, cupping a cigarette in his hand, was walking a wire-haired along the curb between Park and Madison. Babe figured that during the whole time of the Bulge, the guy had walked that dog on this street every day. He couldn’t believe it. He could believe it, but it was still impossible. He felt Mattie put her hand in his. She was talking a blue streak.” Only the child can touch the despair burned into the postwar veteran’s flesh and mind without hurting him. “His mind began to hear the old Blakewell Howard’s rough, fine horn playing. Then he began to hear the music of the unrecoverable years; the little unhistorical, pretty good years when all the dead boys in the 12th Regiment had been living and cutting in on other dead boys on lost dance floors; the years when no one who could dance worth a damn had ever heard of Cherbourg or Saint Lô; or Hürtgen Forest or Luxembourg.” Salinger’s 12th Regiment was being decimated by the war: because of such pain, he will thereafter seek unity in all things.