Exhausted at war’s end, Salinger and the 12th Regiment enter Kaufering IV. In many ways, Salinger never leaves.

DEBORAH DASH MOORE: Salinger would have recognized it from a mile or two down the road. It always amazes me when local civilians say they didn’t know what was going on in the camps; the smell just pervaded the countryside.

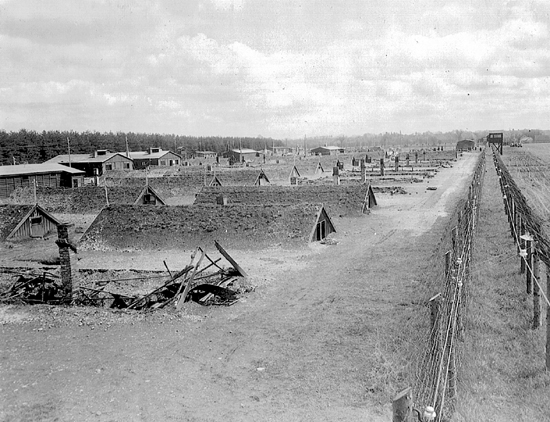

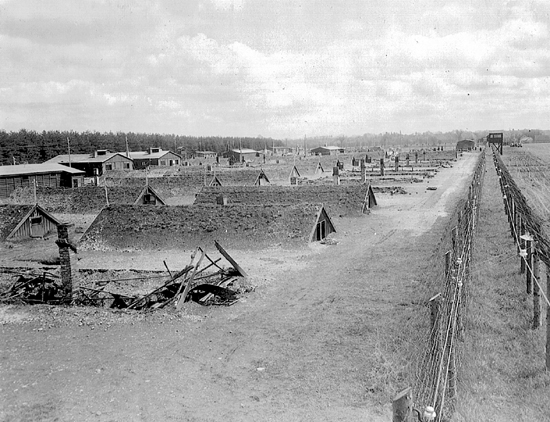

Kaufering IV, subcamp of Dachau.

ROBERT ABZUG: The experience of liberating the camps—the horror, really—began even before they got through the gates.

ALEX KERSHAW: J. D. Salinger was one of the first Americans to witness the full evil of the Nazi regime when he went into a concentration camp in Germany in the spring of 1945. He would have seen unimaginable horrors: burning bodies, piles of burning bodies. It’s a truism because it’s true: words aren’t enough to describe it.

ROBERT ABZUG: You walked through a beautiful, manicured German village, and at the end of the road was this camp that looked like hell piled with corpses.

For a soldier like Salinger walking into a camp, there was a stillness to it and a craziness to it. You were caught off guard. You weren’t psyched for battle. These weren’t liberations in the sense of busting down the gates or anything like that. The war was over; you could let down your guard a little. These soldiers basically walked into these horrific situations. Unguarded and unsuspecting, they were walking into an open place. This was like opening up, and falling into, a graveyard.

EBERHARD ALSEN: Salinger has never described in writing what he witnessed at the Kaufering concentration camp, but it permeates his life and work.

SHANE SALERNO: He did comment on it to his daughter, Margaret, and to Jean Miller.

MARGARET SALINGER: As a counter-intelligence officer my father was one of the first soldiers to walk into a certain, just liberated, concentration camp. He told me the name, but I no longer remember.

J. D. SALINGER: You never really get the smell of burning flesh out of your nose entirely, no matter how long you live.

Burned corpses at Kaufering IV.

JEAN MILLER: He did not talk about the war and his experiences in the war. The only thing he said to me once is that you never forget the smell of burning flesh.

—

EBERHARD ALSEN: Kaufering IV was a catchall camp for the sick prisoners of the other small camps in the area. It was called the Krankenlager (camp for the sick), but it was actually an extermination camp, because the sick prisoners were simply allowed to die from their illnesses or from starvation. On the day before American troops occupied the area, the SS guards evacuated some three thousand prisoners via railroad boxcars and killed all those who were too sick or too weak to travel. They shot, clubbed, and hacked to death ninety-two prisoners, and they burned alive eighty-six others by locking them in wooden barracks and setting the barracks on fire. When the Americans arrived, all the SS guards were gone and only a handful of prisoners were still alive. They had escaped extermination by hiding from the SS. In addition to the 360 prisoners whom the SS had killed before pulling out, the GIs found two mass graves containing the bodies of another 4,500 prisoners who had died from sickness or malnutrition.

The SS evacuated people from Camp IV, the one that Salinger came upon, and as the SS was trying to march them to railroad cars, a lot of the inmates tried to escape and the SS butchered them with machine guns. Some bodies were actually cut in half by machine-gun fire. The SS had also slaughtered them with axes. The GIs found bloody axes next to the corpses.

So as Salinger and his driver drove up to the camp—as a counterintelligence officer, Salinger had access to vehicles other soldiers did not—they saw the almost one hundred corpses lying in the area between the camp and the railroad siding. Then, entering the camp, they saw stacks of emaciated corpses. Salinger and his driver continued into the camp and found the source of the terrible smell: there were three barracks buildings, nothing much more than large doghouses, half underground, and these buildings the Nazis had nailed shut with the sick people inside and set on fire. Salinger and his driver saw the burned bodies still smoldering in those ruins.

Bodies at Kaufering IV.

ALEX KERSHAW: They were behind barbed wire, starved, beaten, tortured, killed.

ROBERT ABZUG: It was the shock of seeing something unexpected. Kaufering was discovered a day or two before the main camp of Dachau. None of these troops had seen anything like it.

EBERHARD ALSEN: The German SS realized the Americans were approaching. They tried to evacuate all the able-bodied prisoners in so-called death marches. In the case of the camp that Salinger visited, the Krankenlager, the camp for the sick, a lot of the people there were unable to walk, so these people were killed by the SS.

When American soldiers discovered the abandoned camp on April 27, 1945, they were greeted by the smell of burning bodies, as the SS had set fire to several earth huts full of prisoners and shot all those who tried to escape the flames. As they went into the camp, the U.S. soldiers saw corpses that had been stacked like cordwood, as one soldier said, and as they looked at these bodies, they saw that they were only skin and bones. The estimate is that most of them weighed between fifty and seventy pounds. They had obviously been starved to death.

Most of what the GIs found were bodies.

JACK HALLETT: The first thing I saw was a stack of bodies . . . that appeared to be about 20 feet long and about as high as a man could reach. . . . And which looked like cordwood, stacked up there. The thing I’ll never forget was the fact that closer inspection found people whose eyes were still blinking, three or four deep inside the stack.

DEBORAH DASH MOORE: The camp assaulted Salinger, as it did any of the soldiers who entered it, with the smell and also with the sight of naked bodies stacked up in piles—bodies that looked like they were dead people, but sometimes sounds coming from the bodies and soldiers realizing that in fact they were still alive. They discovered people who were so incredibly thin that their cheekbones stuck out almost like horns. Their wrists protruded. The skin was stretched over their bodies like a nylon stocking: you could see through it to the bones. Nothing in their experience—and Salinger was an experienced soldier by this time and had been through terrible battles—nothing in their experience could have prepared them for the sight.

ALEX KERSHAW: As Salinger looked at them, these men would duck their heads in submission. They looked like beaten dogs. They were afraid to look another man in the eye in case they would be shot or killed or beaten. That image—of men who couldn’t even look their liberators in the eye—remained with many of those Americans for the rest of their lives.

SHANE SALERNO: Paul Fitzgerald, Salinger’s close friend and fellow CIC agent, was next to Salinger when they liberated the camp. A female survivor handed Fitzgerald a stack of photographs she had of the atrocities that had occurred at Kaufering IV. Fitzgerald held onto these photographs and didn’t show them to anyone until 1980, at which point he sent them to the Holocaust Library and Research Center of San Francisco, writing, “I have had this album for thirty-five years now. . . . This is my own personal memory of a terrible nightmare.” Max R. Garcia, the director of the Center, wrote to Fitzgerald’s intermediary, August Carella, “Please convey my thanks to Mr. Paul J. Fitzgerald for allowing me to see the album of the gruesome photographs he brought back from his WWII days. The photographs of the torture devices I have never seen before and they are indeed eye openers. It and the other photographs clearly indicate the brutality of the Nazi regime that reigned at that time.”

ROBERT ABZUG: Soldiers like Salinger, any of the GIs coming into these camps, were shocked, but they somehow had to make human sense out of it all. They’d look at bodies and try to find some human feature, some lifeness. The living dead were even worse for them to confront, because they would stagger right into their faces and sometimes try to embrace them.

When American GIs walked into a camp, the shock was so horrendous that they’d just break down in tears. They’d fall on the ground. Some of them had to be immediately treated by doctors. These are the liberators I’m talking about now, not the inmates.

Medieval painters painted visions of hell, but this was the real thing: a graveyard of corpses and half-dead people. Imagine walking into a place where there are skeletal remains and burnt bodies and the smell of flesh. The stench was impossible to deal with. You would see people piled high on bunks, two and three and four deep. Some were dead, some were alive, and it took some time to figure out who was dead and who was alive. All were gaunt. Their eyes bugged out of their faces. They whimpered. There was the smell of urine and feces and rotting flesh.

ROBERT TOWNE: Eisenhower saw Buchenwald and Dachau the minute they were liberated. His reaction to them was instructive. He insisted that cameramen from all over the world get there and photograph these things. He pulled General Patton and other officers in and said, “You’ve got to look at this, because there will come a time when people will not believe that this actually happened. It’s too appalling.” All you can say for sure is that for someone who was there, it would be the existential moment of his life. It would have to have a lifelong effect on you. I can’t imagine it otherwise.

ROBERT ABZUG: There is a famous photo of Kaufering Commandant Eichelsdorfer, standing amid the dead bodies, and the odd part about it is, there he is. He has a straight face, as if this were everyday work. That was the way it happened. The numbness the GIs felt from the sensory overload the Germans also felt, not only because they were ardent Nazis but because they came to live with it. It was daily life, whether you were a guard or a commandant. It was a job. It’s clear in the photograph that this was the everyday world for Eichelsdorfer.

Johann Baptist Eichelsdorfer, the commandant of Kaufering IV.

ALEX KERSHAW: As Nazi Germany fell apart in the spring of 1945, the prime objective of counterintelligence officers like J. D. Salinger was to try to find the criminals, the Nazis who had created the unimaginable. I befriended an intelligence officer who had the same rank and interrogation duties Salinger had in the spring of 1945. On one occasion, the officer entered a camp hospital, searching for Nazis. He discovered a few in the hospital beds pretending to be wounded or concentration camp survivors—Germans who had taken the shredded uniforms of camp inmates to avoid arrest, pretending to be Jewish forced laborers. They looked unnaturally healthy compared to their disguise. The officer told me counterintelligence officers lost patience with German prisoners after they discovered the camps. Uncooperative Nazis received severe interrogations. It was very hard for interrogators to remain patient when they knew the well-fed German in front of them had probably shot and killed countless civilians.

ROBERT ABZUG: Some GIs handed their weapons to the few healthy prisoners and allowed them to tear apart or shoot (or both) captured German camp guards. There was a whole cycle of almost uncontrollable revenge. It got out of hand for a little while. For a soldier like Salinger, who’d been through so much violence, one would have to wonder, what was the final psychic straw in this illogical world turned upside down? At least in battle you had an enemy.

There was something different about the liberations that pushed soldiers like Salinger over the edge. When you’re in the military and fighting battles, there is logic to it. When the soldiers came upon these camps, there was no battle to win. They were at an extremely vulnerable moment, because for most of them this was the very last thing that was going to happen to them during the war.

—

EBERHARD ALSEN: The fact that Salinger was half-Jewish must have made his experience of seeing the atrocities that the Germans committed against Jews even more devastating.

ROBERT ABZUG: Here he was, a survivor of horrendously anonymous, mechanized killing on a vast scale, but the pervading horrors of the camps reminded him he was Jewish.

LEILA HADLEY LUCE: I never thought of Jerry as being Jewish. I never thought of any of my friends as being Jewish. They were just friends. He did remind me that he was very concerned about the Holocaust. He was very emotionally distressed by this, and by the concentration camps.

DEBORAH DASH MOORE: Salinger and the Allies discovered what had been done and wondered, Did we actually win the war? Or did we come too late? Mind-eating questions with no appropriate answer. They already knew; they’d seen and fought it. Europe was a graveyard. Suddenly it was a massive Jewish graveyard.

DAVID SHIELDS: While he was not on the front lines of combat, he was certainly on the front lines of the Holocaust, and it stayed with him forever.

RICHARD STAYTON: We have a hard time understanding, because we aren’t Salinger; we weren’t there. I’ve known other GIs who liberated camps and weren’t Jewish. The experience broke apart their psyches, too. They’ve never recovered, either.

—

ALEX KERSHAW: Of the 337 days the war lasted for the American soldier in Europe, Salinger was in combat for 299. How damaged he was we don’t know. After two hundred days of combat, you are insane. They did the studies. Even the strong guys, after two hundred days, would lose it. After taking another village, they’d be found somewhere on their own, crying silent tears. Salinger’s division was in combat longer than any other division in the European theater. He saw the worst fighting you could possibly see, maybe, in the entire Second World War. Anyone who lived through this level of fierce combat this long would have been profoundly affected.

PAUL ALEXANDER: Salinger told [Whit] Burnett he simply could not describe the events of the last three or four weeks [of the war]. What he had witnessed was too horrendous to put into words. Yet even as he was making this gut-wrenching and dramatic revelation, Salinger still felt compelled to discuss, of all things, business. Apparently, Burnett had last written to suggest that Salinger publish his novel before his story collection. In response, Salinger agreed, adding that he could be finished with the novel in six months once he returned to the States. That’s how Salinger left it with Burnett before he thanked him for accepting “Elaine,” the story the New Yorker had rejected. “Elaine,” which centers on a mildly retarded girl with few prospects for happiness, was a longish, informal-feeling piece written before Salinger’s experiences in late 1944.

J. D. SALINGER (“Elaine,” Story, March–April 1945):

But now—the sudden vast, lonely expanse of a deserted public beach at dusk came as a terrible visitation upon her. The beach itself, which before had been only a fair-sized manifestation of tiny handfuls of hot sand which could slip with petty ecstasy through the fingers, was now a great monster sprawled across infinity, prejudiced personally against Elaine, ready to swallow her up—or cast her, with an ogreish laugh, into the sea.

—

ALEX KERSHAW: I talked to liberators of the camps who said the prisoners would go to the wire and hands would be thrust through, hands that you could hardly recognize as a human hand. There was bone and it was begging. For what? Maybe the flesh the GIs were wearing.

ROBERT ABZUG: The scene is not one of battle; the scene is one of the desecration of humanity. One soldier talked about living skeletons’ feeble attempts to applaud the liberating GIs. They couldn’t even put their hands together properly; it was almost like act without sound.

DEBORAH DASH MOORE: At the beginning of Nine Stories Salinger asks the Zen question: What is the sound of one hand clapping? Well, we know the sound of two. One of the Jewish soldiers who entered a camp heard the sound of people trying to clap for the American GIs. Because there was no flesh on their hands, it sounded strangely muted, otherworldly.

ALEX KERSHAW: For Salinger and his generation of Americans who liberated those camps, the legacy of the war hung on that disconnection, those memories, and many other war moments like it, where at the end of all the suffering and dying, you came to a place of irrefutable justification for the preceding slaughter, a hell needing redemption—you came face-to-face with the greatest victims of that war, the Holocaust victims, but the event has destroyed human experience as they all knew and once understood it. In the memory of witnesses like Salinger, there was nothing that could cleanse or salve, resurrect, or make sense of it. Even those rescued were destroyed.

Kaufering IV.

In Salinger’s greatest triumph is the worst tragedy. In the last chapter of a war out of proportion to any that had gone before, of good-versus-evil where good had won, the good, soul-cleansing final chapter was, perhaps, the most soul-destroying and disillusioning.

LESLIE EPSTEIN: We know, as Seymour [a key figure in many of Salinger’s stories and novellas] knew, what men are. No more naïveté, no more denial. There isn’t one of us who isn’t in some way writing about the war—and the Holocaust, too, though we may not fully know it.

—

ALEX KERSHAW: It had been an epic and enormously costly deployment for the 4th Division, an incredible journey. Salinger saw the worst fighting you could possibly see. It’s impossible to imagine what Salinger must have experienced as he endured such enormous pain and suffering and damage done to other human beings around him. He had seen the worst that man can do to man. What Salinger experienced was a continual assault on his senses, physically, mentally, spiritually.

EBERHARD ALSEN: Salinger’s daughter, Margaret, examined the letters that her father wrote during the spring and summer of 1945 and reports that his “handwriting became something totally unrecognizable.”

DAVID SHIELDS: It’s hard not to make the case that, in some sense, the war finally caught up to Salinger.

EBERHARD ALSEN: Salinger’s nervous breakdown was not due to the stress of combat . . . because he was not an infantryman. Kaufering Lager IV was what broke Salinger.