Jean Miller.

Jean Miller.

Salinger meets a fourteen-year old girl, Jean Miller, and over the next five years corresponds with her, dates her, and seduces her. The same pattern recurs throughout his life: innocence admired, innocence seduced, innocence abandoned. Salinger is obsessed with girls at the edge of their bloom. He wants to help them bloom, then he needs to blame them for blooming.

SHANE SALERNO: When Ian Hamilton was researching his book In Search of J. D. Salinger, he visited the archives of Time magazine. In the research folders was an item from the West Coast correspondent that was never published. It read, “We have found a lead that may finally open Salinger’s closet of little girls.” Apparently, Richard Gehman, who had clashed with Salinger when editing his stories at Cosmopolitan, had provided Time with the tip that Salinger, in his early thirties, had once proposed marriage to a teenage girl. The research speculates that this girl may have been the model for Sybil in “Bananafish.”

According to Hamilton, the parents of the teenage girl ended the match, but the friendship lasted “two years.” Time tracked down the girl’s father, who told them that some “ten years earlier,” around 1950, “he and his family had met Salinger at a hotel in Daytona Beach, Florida.” The father wrote, “He fastened on my daughter, J——— and spent a lot of time with her.” J’s father speculated that Salinger’s standoffish behavior—“he didn’t mingle much”—might be attributable to Salinger’s being Jewish. “I mean, I thought he might have a chip on his shoulder.”

The Time reporter’s ensuing memo, according to Hamilton, noted: “This establishes that J (the girl) met JDS in Florida. Check pub. dates of Esmé and Bananafish to determine if J, at 16 or 17, could have been the wellspring for either of these fictional girls. Secondly we should redouble our efforts to find a divorce record in vicinity of Daytona”—that is, might J have been the cause of Salinger’s divorce?

Time reporter Bill Smith located and interviewed J, now married. He reported, “J tried to be aloof . . . didn’t remember where she had met Salinger or what he was like. Well, did she deny that, as a child, she had known him in Florida? She puffed on her cigarette a moment, as if debating over which plea to enter: ‘Yes,’ she said carefully. ‘I think I do deny it.’ ”

Smith’s take on J’s response was this: “There is only one reasonable conclusion: that she is lying, presumably to protect Salinger.”

The initial “J” is all we had to work on. We did a lot of research and concluded that Time came up empty because the magazine not only had the date wrong (it was 1949) but also J’s age was wrong (she was fourteen). Finding Jean Miller took years of detective work, and finding her was only the beginning. For sixty years she had kept silent about her relationship with Salinger. It took a number of conversations over many months to convince her to reveal exactly what happened in 1949.

JEAN MILLER: We were in Daytona Beach, and I was sitting at this rather crowded pool at the Sheraton Hotel, by the beach. This was January or February 1949. I was from a little town in upstate New York, and my family always went to Florida for the winter. I went to a little private school there for three or four months, from eight to one, and then I’d spend the afternoons on the beach or by the pool, reading, doing homework.

I was reading Wuthering Heights, and a man said to me, “How is Heathcliff? How is Heathcliff?” He said it, I don’t know how many times, but I was concentrating, and I finally heard it peripherally. And I turned to him and I said, “Heathcliff is troubled.”

Salinger and his sister, Doris, vacationing in Daytona Beach, Florida.

I looked at him. He had a long, wonderful, angular face and deep, brooding, sad-looking eyes. He was in this terry cloth bathrobe, and his legs were very white; he was very pale. He wasn’t exactly shivering, but he didn’t look like he belonged at this pool.

J. D. SALINGER (“A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” The New Yorker, January 31, 1948):

“He won’t take his bathrobe off? Why not?”

“I don’t know. I guess because he’s so pale.”

JEAN MILLER: He looked old. And he was not going to stop talking, so I put my book aside. We began a conversation, and he was very intense. His mind seem to skitter over various topics. He told me he was a writer and that he had published a few stories in the New Yorker, and he felt this was his finest accomplishment.

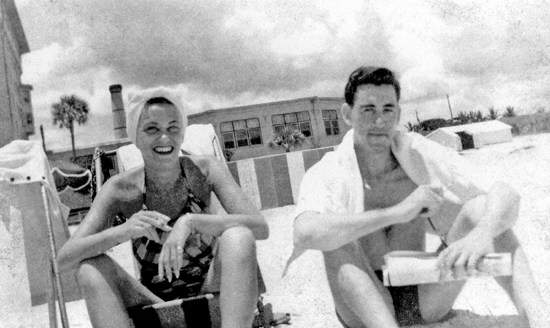

Jean Miller, age fourteen, on Daytona Beach.

We sat there talking for quite a while, and finally he asked me how old I was, and I said fourteen. And I remember very clearly his grimace. He said he was thirty. He made a point of saying that he was thirty on January first so that, in a way, he was just thirty; he had just come out of his twenties. He was funny, sort of a wisecracking sense of humor. We sat there for quite a while. I left, and as I was going away he told me his name was Jerry. I had no idea who he was.

I saw him the next day, and we began these walks. We would walk down to this old rickety pier and find a bench and sit where the wind wasn’t blowing, eat popcorn or ice cream, and we’d talk. And we’d feed popcorn to the seagulls. He was having a wonderful time. We walked very slowly down to the pier. It was like he was escorting me. We’d do this every afternoon for about ten days.

He was very deaf in his right ear. I think something to do with the war. He would always have his left shoulder behind me and lean down to hear what I had to say. I would do cartwheels on the beach, and then I would whip off into the ocean, and he would love that. I think he felt it was as close to a perfect, maybe even direct moment that he’d had—maybe ever had. These perfect moments: they got him away from his melancholy, his angst about the war. He seemed to take joy out of my childishness. The frivolity and the pure innocence of fourteen-year-old me, I think, is what he was attracted to.

He was very tall, thin, and I don’t know that he was athletic, but he was graceful. He was careful with what he wore; he always looked very neat. He was awfully good-looking. It wasn’t his main attraction, but he was very good-looking.

Jerry Salinger listened like you were the most important person in the world. He was the first adult who seemed to be genuinely interested in what I had to say. No grown-up had really listened to me as though I was a person in my own right. Jerry was interested in my opinions; everything about me he was interested in. He wanted to know about my family, about my school, what games I played. He wanted to know who I was reading, what I was studying. He wanted to know whether I believed in God. Did I want to be an actress?

He began talking about the Brontës, the moors, how he loved the Brontës, how everyone—every student, every adult, every old person—should read the Brontës, read them over and over again. He talked most of that day.

He was not pleased at all with all the slick magazines; they would change names or take out sections or rewrite some sections, and never with any permission from the author. [His stories] would just appear in a form that he didn’t know was going to happen. He was very down on most every publisher, and of course he hadn’t even gone to the book publishing world yet.

He talked about his publishers, what a parasitic group they were. He said publishers were not on the writer’s side. The only publishers that he really had any respect for at all, and actually had a great deal of respect for, were the people at the New Yorker : Harold Ross, William Shawn, Gus Lobrano, William Maxwell. He would wax on about the New Yorker and how it was the only place he wanted to publish. He might publish in Harper’s or Atlantic Monthly, but they didn’t pay as well. He very much liked the idea that the New Yorker didn’t insist upon knowing a great deal about the author. He always felt that what people should know about an author was nothing personal.

He talked about Ring Lardner. He admired Fitzgerald tremendously. He told me what to read, that I should read the classics. Never mind with this modern rubbish. Read Chekhov. Read Turgenev. Read Proust.

He talked about his family, his mother. He adored his mother. His father thought his writing was silly. Self-indulgent.

At night, with the dancing, he was a different person—very gregarious and fun-loving and free. He could be very carefree. He was a very kind, gentle man, very interested in other people. He was not egocentric. He was not a solipsist. He simply was interested in other people.

The Daytona Beach Sheraton Hotel.

SHANE SALERNO: Salinger broke up with his first wife, Sylvia, at the Daytona Sheraton in 1946; he began his seduction of fourteen-year-old Jean Miller at the Daytona Sheraton in 1949; he broke up with Joyce Maynard at the Daytona Sheraton in 1972; and he set “Bananafish” more or less at the Daytona Sheraton. He continually returns to the scene of Seymour’s suicide.

JEAN MILLER: He talked about his novel quite a bit—how he was working on it and had been working on it. At least one story had been published about Holden. Jerry told me there was a great deal of Holden in him.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, undated:

You say you still feel fourteen. I know the feeling. I’m thirty-four and too much of the time I still feel like a sixteen-year-old Holden Caulfield.

JEAN MILLER: One of the things that worried him about The Catcher in the Rye was that usually books are a hit one year and that’s the end of it. You’re gonna be constantly under pressure to write another book. I think that made him nervous because he wasn’t sure he could write another book, that he had a subject for another book; maybe he wanted to go back to short stories.

According to Jerry, during fallow periods, you may not think you’re accomplishing anything, but it’s a form of preparation. And it seemed to him the best way to use the fallow years was to really examine your misery—really examine the position you’re in. That is the waiting time.

He wasn’t worried about his book from an artistic point of view. He wasn’t even worried about it from a financial point of view. He was worried about how it was going to be received by people, particularly people he loved: his parents, various friends. He felt nervous about Holden’s language. Maybe people would find the language unnecessary. But he wanted people to know, absolutely, that he was trying to write a good book—not just a bestseller, a good book.

I felt very free with him. Lent came, and I said I’m giving up popcorn for Lent. Anybody else I had said that to over the age of thirty would have said, “Fine, fine,” but much to my amazement he took it very seriously. He took me very seriously. And because of my age of fourteen, I was very grateful for that. No grown-up had ever really listened to me as though I were a person in my own right.

He talked of Oona O’Neill quite lovingly. Naturalness was a big thing for Jerry. He thought she was unpretentious, almost childlike, and this would very much impress Jerry. Now whether that’s true really about Oona O’Neill or whether he just saw that in her, I have no idea. But he obviously loved her very much, even though he no longer saw her. My impression was that he thought she was wonderful. I heard no bitterness in his voice at all. He told me about some of the times he spent with her.

He talked of his first wife a lot. I don’t know whether she was French or German, but they married in Europe after the war, and I don’t know how they met. He said they kept in touch telepathically.

He did not talk to me about the war.

My mother was taking a dim view of these walks on the beach I was taking with this man. She found out Jerry was J. D. Salinger. She read the New Yorker, and she said, “He looks just like Seymour.” He did, but I didn’t know the story yet. I had no idea who Seymour was. I didn’t care. My mother said, “A man like that is only after one thing, Jean; you better be careful.” She knew he had written “A Perfect Day for Bananafish.”

Those times at the pier were the most carefree and fun: getting to know each other, enjoying each other. Those two days were probably the most fun we had together. Much later he said, “I wish I could have been able to keep you at that pier.” I had never talked to a creative man before. I had never talked to such an erudite man versed in so many subjects. He was very amusing, eyes twinkling and cracking jokes. He saw the humor in things, but it was a very kind humor. If I said something in a gossipy fashion about someone I didn’t know, maybe even something mean about someone, he would defend that person. He would say, “That person has something to offer, even if she’s an old woman and she’s fat. She’s not nosy; she has a great curiosity. You should try to look for good in people. Don’t see their worst traits all the time.”

DAVID SHIELDS: As Zooey tells Franny, “There isn’t anyone out there who isn’t Seymour’s Fat Lady.” Salinger repeated this mantra constantly because he was trying to convince himself of the veracity of Zooey’s claim. The Fat Lady, Zooey explains to his sister, is Christ himself.

JEAN MILLER: He wanted to know what I was studying. He wanted to know everything about me and tried, I think very subtly, to put some thoughts in my mind of how I might, in the future, center myself and make my life around something that I could work for rather than drifting. He made me start my education. It was the beginning of me thinking, and not necessarily in an intellectual way, although that, too, but to get in touch with my center.

He was after that innocence and purity of childhood, which Zen tries to recapture. Living in the moment, fully, totally in the moment, as children do. A state of grace.

He talked a lot about Judy Garland and child actors, the innocence of actors and the beauty of their purity. He liked the innocence of childhood before pretention set in: the clear, simple way she sang in The Wizard of Oz. The direct experience that children had. Learning to walk for the first time. Seeing a camera for the first time. Forming their own opinions. Getting their own experience. That’s very close to Zen.

At the end of his stay in Daytona, his very last day, he gave me a little white elephant as a talisman and said, “Even if we never see each other again, I wish you all the good.” He also said, “I’d like to kiss you goodbye, but you know I can’t.” It was just a given that we were going to write each other. Before we parted he went up to my mother and said in the lobby of the Sheraton, “I am going to marry your daughter.” Well, I can’t imagine my mother’s reaction to that.

Jean Miller’s mother in front of the Sheraton Plaza Hotel.

He wrote immediately; a letter arrived right away, mailed to the Princess Issena Hotel, Daytona, where we were staying. He was living in Stamford, Connecticut. The address was on the letterhead, and he asked me to write him, and would it be all right for him to write me, and I wrote back, “Of course it would be okay.”

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, March 19, 1949:

I arrived in New York with my room key from the Sheraton in my pocket.

It’s good to think that you’re still in Daytona, walking in the sun, sitting in those green canvas chairs by the pool, playing tennis in your red sweater.

Hope you’ll write to me at great length, Jean. It’s cold and bleak up here. Not a seagull in sight. (The seagull has come to be my favorite bird.)

Yours, Jerry

JEAN MILLER: We began exchanging letters. And later he began sending quite a few Western Union telegrams. He always talked about his work. I wrote him about his story “The Laughing Man.” I said I had trouble with the vocabulary, and he wrote back saying that he had trouble with the vocabulary, too. That it was the kind of story that needed big words to hold it together.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, March 28, 1949:

Yours is the only letter I’ve ever had with seagulls in it. Even before I opened the letter, I could hear the flapping of wings inside the envelope. I’ve set a little pre-summer work deadline for myself, and I may not get much of a chance to write you for a few weeks. But if you have time, you write to me—all right? I miss you and think of you.

Jerry

JEAN MILLER: I remember once getting into a big fight on my village green in Homer, New York, after we returned from Florida, with another girl. We had each other down in the grass, and she gave me a black eye and a bloody nose, and I limped home and I called Jerry. Well, he just thought that was wonderful.

He didn’t say, like my mother, “You’re too old to be fighting.” He was a grown-up on my side. He was always on my side. He didn’t judge me. He said, “Well, maybe you should take some karate lessons. Maybe I could get you a Charles Atlas book for young girls. Maybe you’ve got to do something to build up your muscles.” He wasn’t even laughing. Of course, I was crying. That’s what I mean when I say he took me very seriously.

We used to play softball in our front yard, and he’d want to know how many hits I had, how many times I struck out. He loved people my age. He’d instruct me via letter or via phone on my tennis backhand. He didn’t want me to be literary. He wanted to talk about my childhood pursuits.

J. D. SALINGER (“The Laughing Man,” Nine Stories, 1953):

Over on third base, Mary Hudson waved to me. I waved back. I couldn’t have stopped myself, even if I’d wanted to. Her stickwork aside, she happened to be a girl who knew how to wave to somebody from third base.

JEAN MILLER: I remember early on thinking, “How am I going to write this man?” I could be as chatty as him, but I began worrying about sentence structure at the age of fourteen because of him. And there was really no one to ask. I wasn’t going to ask my mother, and no one else knew I knew him. There was nobody who knew. I had no one to ask how to write these letters. There was a lot in me that I did not say to him because I didn’t have the nerve to say. I don’t know what I thought was going to happen to me if I opened up, but I wasn’t taking any chances. I think he sent me about fifty or sixty letters.

SHANE SALERNO: Jean later explained to me that Salinger actually wrote many more than sixty letters to her, but that her mother threw away many of them.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, April 16, 1949:

I’ve been working steadily for weeks, and just finished a very long story. I like it, but the New Yorker doesn’t see eye to eye with me on it.

People seem so sure that a writer’s life is a gay one. No office to go to, no regular hours. All the independence and travel opportunities in the world. And it may be a gay life for some writers. I haven’t found it that way.

JEAN MILLER: He didn’t like Stamford, and after a while he moved back in with his family on Park Avenue. That’s a very funny letter, because he was in his old childhood room and he lists the things that were there to haunt him: invisible-ink pens and rejection slips and hysterical draft notices and invitations to weddings and tennis rackets and Charles Atlas books falling out of the closet when he opened the door. It was very comical, but he was not pleased to be staying back at his parents’ home.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, June 3, 1949:

I grew up in this room, and all the unthrilling landmarks still stare at me in the face. If I open a closet door, I’m liable to get hit on the head with an Old Tom Swift book. Or a tennis racket with shriveled strings. My desk drawers are full of stale memories too. You’re going to be fifteen soon, aren’t you? My best to you, Jean.

Jerry

JEAN MILLER: The next time we met was probably in the spring, when I was in New York City with my family. He came to meet us, and I took a walk with him. I remember exactly what I had on. I had a little tan suit on with little white gloves and a little straw hat. We were walking down the street and the straw hat blew off and I thought, “Oh, how embarrassing.” I was very intimidated in New York, anyway. Tall buildings, beautiful hotels. I was a very small-town girl, which probably was part of my appeal to him. He loved the idea of my hat blowing off; he used to refer to it later. He ran like a child to get my hat and stomped on it because the wind would take it away again. And I remember thinking, “He’s really having fun.”

I was amazed that he would get into this game of chasing my hat. I remember he had very long legs, and he couldn’t run very well, and I remember those knees sort of knocking together as he came back and formally gave me my hat, which was a little bit bashed, and put it back on my head. He laughed about it for about fifteen minutes.

My parents were not about to let me out in New York on my own. I just wasn’t equipped to do that. He made an arrangement with them. The four of us went out to dinner that night.

He found a cottage to rent in Westport, which he described as being in the woods about a mile from town. He was very pleased at first, but decided that [Westport] was too writer-conscious, so he got his own apartment on East 57th Street. By then it was after Catcher in the Rye had been published.

He was getting a lot of attention in New York. After the novel came out, he was very sought after, and he hated that. He hated people’s questions. He hated people’s praises. He hated people’s criticisms. Maybe the criticisms were the worst. People were a distraction. I was having dinner with my parents and Jerry, and a waiter handed Jerry a note from a woman. Jerry went over to her table and spoke to the woman for a couple of minutes and came back. He showed me the note: “Are you J. D. Salinger?” It was all very casual and my only indication of his celebrity.

I always saw boys my own age. At one point I met a boy on a trip to Europe and visited him at Middlebury, where I boasted that I was a friend of J. D. Salinger’s. I was more cognizant then that he was famous. The boy I told this to called him up for an interview. He told the boy he didn’t do interviews. Jerry reprimanded me gently. He said, “If he was a beau of yours, [I] should have said yes and shot him on the spot.” In a distant way he was very tender.

At that point he had moved to Cornish, New Hampshire. He said his friends were concerned about his move to isolation, particularly the ones who liked his fiction. They thought he would lose touch with people and therefore have nothing to write about. It didn’t mean he was a hermit. He just didn’t want to be with writers. And he certainly didn’t want to be the toast of New York. He said there were literary parasites and he didn’t want anything to do with them.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, April 30, 1953:

I planted some vegetables yesterday. Since then, I’ve gone out every hour on the hour to see if anything’s come up. Have no idea how long it takes for a seed to turn into a carrot.

JEAN MILLER: I was at a place called Briarcliff Junior College, in Briarcliff Manor, New York, which isn’t far from New York City.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, April 30, 1953:

You don’t think you’ll be invited back to Briarcliff next year? Maybe you’re exaggerating. If the school has any real sense, it’ll take you back. You’re probably the only girl with any style there. Lousy grades, maybe, but style.

JEAN MILLER: I remember when I would speak to him about school he was very down on education. “Don’t believe everything your professors say,” he would tell me. “They’re just giving you information. Get your own information on your own terms. Stay detached.” This was a theme throughout Jerry’s life—professors insisting in a pedantic way on students regurgitating knowledge. No direct experience of learning, of spontaneity, of creating.

I think you can see it in [Salinger’s fictional character] Teddy, who says, “I would bring in an elephant, and I wouldn’t tell the children that this elephant was an elephant or that it was gray or that is a trunk or this is an ear. I would let them have that direct experience themselves. I wouldn’t tell them grass was green. Green is just a color.” Jerry quoted Mary Baker Eddy: “Nothing is good or bad; it’s what we think that makes it so.” His whole life was built on this: trying to reach the state of grace through mysticism. If it hadn’t been for Jerry Salinger, I never would have gone through the—gone below the surface at all in my life. A Bhagavad Gita quest. A seriousness in my life: questioning things, learning things, learning things on my own.

Jerry would often send me airline tickets to come visit him.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, October 5, 1953:

What a good girl you are, and if things go too roughly this winter—what with parental pressure, etc.—you can arrive up here any time you feel like it, bag and baggage, cigarette holder and all, and I’ll share my homely fare with you.

It’s easy and quick to fly up here. North East Airlines, out of LaGuardia, makes West Lebanon in an hour and forty-five minutes, and that’s only ten minutes by car from me. Smith’s taxi service, in Windsor, now know where the hell my house is.

JEAN MILLER: I remember his Cornish home; it was difficult to get there. I was very aware that Jerry Salinger didn’t want to be talked about as J. D. Salinger. I might have spoken vaguely about my friend Jerry to my friends, that I was going to New Hampshire some weekend to see him. But I would never say, “I am seeing J. D. Salinger.” After that experience with that boy, I was even more careful.

There was never an inkling of anything physical between us until much later. I would go up to Cornish; I’d spend the night with him in the same bed. Me over here, him over there. This happened several times because there was no place else to sleep. We were camping out. It’s absolutely the truth. It was a genderless relationship. We were friends. We were buddies. Sex did not come into it.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, undated:

I was oddly touched that you’d made the bed before we left the house. It amounts to a beau geste, and I’m duly grateful.

JEAN MILLER: I remember once, probably pretty early on, we were in a bookstore. I tentatively picked out Lady Chatterley’s Lover. He looked at me and said, “You don’t want to read that.” I put it right back. He was very puritanical. He enjoyed being childlike. He didn’t like adults particularly. I probably would have fallen into bed with him at about the age of three if he’d asked me, but he didn’t. Somehow it never occurred. As long as it didn’t occur to him, it didn’t occur to me.

DAVID SHIELDS: Salinger’s seduction process: adore childhood innocence in a pubescent girl, seduce it and her into (barely) adulthood, reproduce the assignation in his writing, and compare actual physical contact to Esmé or Zen—a comparison no human can survive.

JEAN MILLER: He had a wonderful view of Mount Ascutney. I remember sitting by the fire and dancing with him at night to Lawrence Welk or Liberace or something like that. He liked to dance, Jerry. It was fun. We would look at the people on television dancing and we just would waltz, laughing all the time. He laughed a lot. He seemed filled with joy a great deal of the time. He could be like that when he had guests, too. He was such a big character.

I also remember seeing two beautifully leather-bound books, The Catcher in the Rye and Nine Stories. And I know from back in Daytona days that he fought being a consumer. He did not want to want things, but leather was a great temptation for him. He just couldn’t resist doing that.

He said to me, “I don’t belong to you and you don’t belong to me, and we just see each other and have this great time.” He told me in October 1953 that nothing had changed for him since Dayton Beach.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, October 1953:

It still seems completely good and meaningful to see your face and be with you.

I simply think you’re a beautiful girl in every sense.

JEAN MILLER: At one point, he asked me to move in with him. That letter doesn’t survive. I showed it to a friend of mine, a boy from Amherst. I never, ever would have done it because my parents had too much control over me. But I did think about it. And I thought I could never really survive up there. I had been there. I could see what would be expected of me, which was pretty much drudgery, and I was just too spoiled. I had too much self-interest to really take that invitation seriously.

I began to worship him, which is maybe too strong a word, but I was still young. It had nothing to do with his physical appearance. It was his powerful, brilliant mind. His sheer strength of character. Of the rightness and wrongness of things. The way you should look at things. He was a very persuasive man. He never talked about people.

I’m afraid you do compare other men that come in and out of your life to him. His intensity and his curiosity. His—I was going to say “charm,” but I don’t know that he necessarily did have charm. His knowledge. Scratch “knowledge.” His wisdom. I’ve known people that have approached it, but not totally. I had a wonderful husband who approached it. But I mean there’s no point in looking.

Here was this fascinating man who seemed to like me, and I think in one of the letters he says that we have put each other on pedestals. And if anything is to become of us, we’ll have to get rid of those pedestals. We were just sort of dancing on these pedestals, not getting any closer. Both of us would’ve had to fall off a pedestal. Otherwise I cannot imagine a marriage.

He never told me his real vulnerabilities. We weren’t terribly close. I did not feel like a unit with him against the world, as I did with my husband. I was in awe of him. I was tongue-tied. I was gun-shy. He was up there and I was down here. I really didn’t know what there could be in me that could affect him.

Jerry Salinger remembered me always on that pier in Daytona Beach, and I was beginning to change. He wrote about my change. He went on to say in another letter how little really he knew about me. There were great parts of me that he didn’t know.

I had grown from a little girl to a young woman. My feelings for him developed as I developed. I think he thought I was much brighter than I really was. I’m not saying I’m stupid, but I am saying that I just don’t think I was the sensitive person he thought I was. I just knew it in my gut. And there was no point in me trying to be. I was a woman and I was trying to look my best, and when I would meet him, I would do the best I could. We used to meet at the Biltmore under the clock, or he would take me to the Palm Room at the Plaza, where I’d loved to go as a little child. He took me once as a little girl to the Palm to listen to the violins and have tea sandwiches.

Or we’d go to the theater. I remember seeing the Lunts onstage once. I don’t remember what play. And that’s when he said to me, “Would you like to be an actress? Have you thought of being an actress? I think you should maybe think about being an actress.”

He took me to the Stork Club; it was great fun. Other times we’d go to the Blue Angel to hear music. Wonderful atmosphere and greedy-looking people sitting around eating fat steaks and smoking cigars with lots of drinks. You felt as if you were in an important place. I was a woman. He was courting me. We would do things that courting couples do: go to the theater or go to nightclubs.

When he first saw me, he told me, I was talking to an older lady and I yawned, but I stifled the yawn—which is what Esmé does in the story, when she’s singing in the choir. He told me he could not have written “Esmé” had he not met me.

Jean Miller, age eighteen.

But he never told me he was in love with me. He wouldn’t always come to New York to see me. He wrote me in one of his letters that he’d made promises to himself. He had to write in Cornish, and he was writing something very autumn, with autumn thoughts, right now, and he couldn’t face concrete. In his letter he said what an unromantic man he must seem at that moment, that I’d have every right to tell him to go jump in the lake and to go off with some less neurotic person.

He needed to put himself into a cell-like existence. I don’t know that Jerry Salinger necessarily liked the country. I think he probably grew to like the country, but the only thing he wanted to do was write. He went someplace to write that he knew he was going to be comfortable in, and he made it work for himself.

Since deciding to write, he didn’t really have a free life. He couldn’t take even so much as a drive in the country without having the weight of words on him, pushing him down, whereas a businessman could go for a drive in the country and turn it off. Really he could take his typewriter anywhere. His traveling was not really traveling. It was just taking his typewriter someplace else geographically.

SHARON STEEL: In a letter to Michael Mitchell (the artist who designed the original jacket for The Catcher in the Rye) dated May 22, 1951, Salinger writes from London, detailing his experiences sharing drinks with a Vogue model he met on the ship. (“No real fun, though.”) . . .

Later, he hangs out with Laurence Olivier (“a very nice guy”) and his wife, Vivien Leigh, whom he calls “a charmer.” Salinger finds himself at a party—where he accidentally snorts gin up his nose—with the Australian ballet dancer Robert Helpmann, described as a “sinister looking pansy,” and argues with Enid Starkie about Kafka. He also goes to see a play and compares the theater in New York City to that in London’s West End. “The audiences here are just as stupid as they [are] in New York, but the productions are much, much better,” he writes to his “Buddyroo,” Mitchell.

JEAN MILLER: His work was his karmic duty. His work was what he had. His work was his whole being. He was so focused on his work. I mean he started out as a romantic and ended up pulling back. That’s the way I viewed it.

I went to Briarcliff in 1952 and got out in 1954. I was nineteen or twenty. He would come to visit and we would go out to dinner. I remember particularly that he came when I’d had a fencing lesson. Fencing always made me perspire, so my hair looked wonderful. I remember being very pleased about that. He’d be standing at the door, not really wanting to come in, not wanting to be recognized. He’d whisk me away and we’d go up to a restaurant near the Tappan Zee Bridge.

Sometimes he would take me out for an evening in New York. I remember once seeing the George Washington Bridge lit up and thinking how absolutely beautiful—it was insane how beautiful it was. He laughed and said, “Jean, you’ve got to learn not to say the obvious.”

One night he took me for drinks at the Maxwells’ [William Maxwell, the writer and New Yorker fiction editor, and his wife, Emily], and I remember that particularly because I loved them both. I had a little watch that my grandmother had given me. It was a Tiffany watch and I kept losing it, leaving it in Cornish or leaving it here or there, and Jerry said something about the watch that wasn’t true. I don’t know what it could have been. But I contradicted him and both the Maxwells said, “Good for you, Jean, good for you.” As though I, this little girl, had contradicted Jerry, and Jerry wasn’t used to being contradicted.

Only once did I ever hear him speak of being a half-Jew. It was dinner at the Maxwells’. I gathered that his Jewishness was a problem to him. He asked me to sort of back into the ending of “Down at the Dinghy.” “Don’t be shocked.” Or “You may be shocked. I had to write the story. I’m sorry I wrote it, but I had to write the story just once.”

I think he was enjoying me as a child all those years. I’m the one who changed it. We were in the backseat of a taxi and I turned and kissed him. It was very natural. I wanted to kiss him, so I kissed him. I suppose I gave him permission—“It’s okay now”—but it would never have come from him. Well, probably it would have, but I did it first. My daughter thinks it was important to him to wait for me to reach the age of eighteen before we had sex. I don’t think that.

Soon after the cab kiss we went to Montreal for the weekend. I don’t remember very much about it, but I do remember sitting in a restaurant and there was a lovely-looking girl who looked very shy and uncomfortable. I remember Jerry commenting on her. There were also two very businessmen-like people talking about mysticism.

We went up to our room and we went to bed. I told him I was a virgin, and he didn’t like that. He didn’t want the responsibility of that, I guess. The next day, having had my rite of passage, we flew back to Boston; from there, me on to New York and he on to West Lebanon, New Hampshire. Somehow, during the flight to Boston, he got the idea that his connecting plane was canceled. I began laughing because I was delighted that we could spend the afternoon together. I saw this veil come down over his face. I saw the look on his face. It was just a look of horror and hurt. It was terrible and conveyed everything. I knew it was over. I knew I had fallen off that pedestal.

I didn’t have a plane until later in the day. He went right to the desk, got the ticket changed, hustled me right onto an earlier plane. There was no questioning, discussion, no ambiguity. I had come between him and his work, and it was over. I got maybe one or two letters from him after that, which don’t survive because I was too upset. I suffered, but I also blame myself. After all these years I should have known what he told me. Read the letters. All those letters say, “My work has to come first.”

It was extreme, particularly after what had just happened to us the night before, but it had to be. I had no choice but to accept it. I think he all of a sudden realized I was a phony, and that’s his word, “phony.” That’s what I think he thought. Because of being a virgin, which I had never told him. All of a sudden he saw me in an entirely different light.

There was never any question in his mind that he was a writer and that’s what he was meant to do: write. It was a Bhagavad Gita duty, as far as he was concerned, although he hated the word “duty.” His work was ordained by God. It was his way to enlightenment. He was put on this earth to write. And I became a distraction; it took only two minutes to become a distraction. I was just devastated. I suffered, but I got over it. I had to get over it.

Zen was something that he talked about a lot. In one of his letters, he said, “I’m sorry you couldn’t go to the basketball game tonight. There was Zen there.” Zen is where you find it. These were perfect moments for him.

In 1955 I was in Daytona again. I was in the Ocean Room, dancing. I looked out a window, and there was Jerry Salinger with this beautiful girl. They sort of looked married to me. Married or not, they were together. They just were a beautiful couple. He was a very good-looking man. She was a lovely-looking woman.

They were walking along. It was above the pool on a walkway, and they looked very comfortable together. They were obviously out for an after-dinner walk. I can’t say they looked ecstatically happy. They weren’t necessarily arm in arm, but they didn’t look unhappy. They looked simpatico.

I was very taken back. I was looking out this window, dancing with somebody, and there he was. I was driving down Main Street the next day and I saw him walking from a bar where I had been with him, where he and my father used to have drinks together, with this woman on his arm who became his second wife, Claire Salinger.

How did I feel? I didn’t feel good, but I was powerless to do anything about it. That was the last time I ever saw him. I was shocked when I saw him at that window, but he saw me. I know that. Our eyes met. He saw me. And the next time I looked again, he was gone. They were gone. I had known it ended quite a while before that moment.

He always told me that when you run into somebody, if you get all shy, there’s still something there.

When Jerry Salinger was through with somebody, he was through. I knew that he was very definitely out of my life. I adored him and we had a wonderful five years, for which I am very grateful. I am very grateful to have known him. He changed me, but I didn’t know it at the time.

He was an avuncular figure in my life. He was my buddy. I never felt—except for the letters—I never felt adored by him. I never felt that he in any way needed me. I felt very close to him, but it seems to me we had parallel lives until the end, and then that turned out to be a disaster. I was damaged by our relationship, in the end. I was. However, that is offset by almost five years of learning, joy, fun, my mind opening up to all sorts of things.

Jerry sent me two books for Christmas: “To Jean, from Jerry, December 1953”—Eugen Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery and The Sutra of Hui Neng. Then he wrote me a long letter explaining to me as best as he could about Zen, which is living in the moment. It’s having direct experience, forgetting your ego, losing your ego. People should work against having egos. Childlike, pure, nothing between you and experience: that is the way, according to Jerry Salinger, life should be lived. His great lesson was detachment. All through my life there’s a part of me that asked, “Would Jerry Salinger approve of this?” I can go five years without giving him a thought, but if there’s a moral dilemma and I’m trying to figure out what the next right step is, Jerry Salinger might pop in my head. I think, “Well, I better not do it that way.” Of course, it’s difficult if you’ve been with a man like Jerry Salinger; you do compare other men who come in and out of your life to him. His intensity and his curiosity. His wisdom.

Besides the letters I have from him, there is one thing that will always serve as a memory of that special time long ago, and that is Jerry’s wonderful story “For Esmé—with Love and Squalor.” He told me he could not have written it if he had not met me.