Claire Douglas as a Radcliffe student.

From the late 1940s onward, Salinger becomes increasingly committed to Eastern philosophy and religion, especially Vedanta. Visiting the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center of New York, going on retreats in upstate New York, and reading sacred Hindu texts, he bases virtually every decision of his life on Vedanta’s tenets. Vedanta’s prescription for the second stage of a man’s life: become a householder—marry and create and support a family. Salinger marries Claire Douglas, the model for his story “Franny,” and is a member of three families: his own; the fictional Glass family; and a third, the New Yorker of editor William Shawn, enabler of Salinger’s obsessions, especially purity and silence and (ultimately) the purity of silence. Salinger writes, obsessively, in a bunker separated from the main house. Salinger talks as if his fictional characters exist in the world outside the page. He exists in a no-man’s-land among his fictional families, the Glass and Caulfield clans, the pre- and postwar worlds, and the lives of young women he tries to seduce into his imagination and life. As paterfamilias, he is juggling these multiple families. He is trying to save postwar, childhood innocence from his own postwar trauma. The implicit tension is bound to cause destruction.

PAUL ALEXANDER: Following the episode with Shirlie Blaney, Salinger decided to go out and reconnect with people in his community. He was looking to become friendly with older people, going around to various parties he was invited to.

SHANE SALERNO: In fall 1950, Salinger, who was thirty-one, met Claire Douglas, who was sixteen—a senior at Shipley, a girls’ boarding school in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania—at a party given by Bee Stein, an artist, and her husband, Francis Steegmuller, a translator and writer for the New Yorker. Claire’s parents lived in the same apartment building as Steegmuller and Stein, on East 66th Street.

MARGARET SALINGER: She arrived at the party looking strikingly beautiful, with the wide-eyed, vulnerable, on-the-brink look of Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s or Leslie Caron in Gigi . . . Claire wore her chestnut hair smoothed back from her lovely forehead. . . . The night my parents met . . . she was wearing a mid-blue linen dress with a darker blue velvet collar, simple and elegant as a wild iris.

CLAIRE DOUGLAS: God, I loved that dress. . . . It matched my eyes perfectly. I’ve never worn anything more beautiful in my life.

SHANE SALERNO: At the party Jerry and Claire couldn’t talk much, because they came with other people, but the next day Salinger called to thank Bee Stein and ask for Claire’s address at Shipley. The next week she received a letter from him. He phoned and wrote to her throughout the 1950–51 school year.

Claire Douglas as a Radcliffe student.

PAUL ALEXANDER: The moment Salinger saw her he was infatuated with her. She was attractive and very personable. She was pretty in a charming sort of way, and she had a softness and a delicateness to her that Salinger found very appealing. . . . As Salinger grew older, he was consistently attracted to women in their late teens. There was the young woman in Vienna, then Oona O’Neill, and now there was Claire.

Salinger discovered that her father was Robert Langdon Douglas, the well-known British art critic. Interestingly enough, she had been a product of a marriage in which her father was significantly older than her mother, so it wasn’t unusual for her to be attracted to Salinger.

DAVID SHIELDS: Claire came from an illustrious family: her much older half-brother, William Sholto Douglas, served in the British Royal Air Force for most of the 1914–47 period, including both world wars. He commanded postwar British occupation forces in Germany for a year before becoming the chairman of British European Airways. He also became a member of the peerage and the House of Lords. Her father, who enlisted in World War I at age fifty, was an expert in Sienese art. He died in Florence in 1951. Claire was used to being around older men who’d fought in the world wars. Like Salinger, she was also half-Irish.

MARGARET SALINGER: Her childhood was not one that set her up with any kind of foundation. She was sent off to convent boarding school at age five, in and out of eight different foster homes, off to another boarding school.

DAVID SHIELDS: Salinger is interested in very, very young women—girls, really—but so are a lot of men. What’s revealing about Salinger’s fixation on girls is that he views them, essentially, as escapes to a time when no one “had ever heard of Cherbourg or Saint Lô, or Hürtgen Forest or Luxembourg.” (Salinger, “The Stranger,” Collier’s, December 1, 1945.)

GERALDINE McGOWAN: Salinger was an extraordinarily attractive person, with tons of charisma, and from what we know he bombarded everybody with affection at the beginning of the relationship. They were the best, they were the loveliest, they were the smartest, they were gifted. And then he gets them and it ends.

DAVID SHIELDS: The summer after her freshman year at Radcliffe, Claire returned to New York City to model for Lord & Taylor.

SHANE SALERNO: Claire would visit Jerry’s apartment on East 57th Street, where she’d spend the night on his black sheets, but they wouldn’t have sex. Salinger was already under the influence of The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna: “avoid woman and gold.”

CLAIRE DOUGLAS: The black sheets and the black bookshelves, black coffee table, and so on matched his depression. He really had black holes where he could hardly move, barely talk.

SHANE SALERNO: Claire hid certain facts in the early stages of her relationship with Salinger. She hid her Lord & Taylor modeling job from him because she knew his response would be negative.

In 1953, after Salinger had moved to New Hampshire, he visited Claire at Radcliffe, where he wooed her with long conversations and riverside strolls. But in between the visits, he remained distant, and Claire would feel abandoned. When Salinger surprised her by asking her to drop out of school and move in with him in Cornish, she refused. Hurt, he disappeared. Claire was distraught and drove up to Cornish to speak to him, but he was nowhere to be found.

PAUL ALEXANDER: Salinger disappeared when Claire first hedged about moving into his house.

DAVID SHIELDS: Salinger left to spend several months in Europe.

SHANE SALERNO: During this time, he also continued to be in touch with Jean Miller.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, 1953:

I’ve never loved anyone enough, it seems to me, to go up and break the glass walls I’ve put the person inside. It makes it very hard on everybody concerned. Maybe one day I’ll change. I honestly don’t know. I’ve never really felt integrated enough to love anyone freely. I’ve never felt enough like just one man, instead of twenty men.

PAUL ALEXANDER: Claire collapsed physically and mentally. She endured mononucleosis and an appendectomy, landing her in the hospital for quite a period of time. A Harvard Business School grad named Coleman Mockler who was infatuated with her repeatedly visited her in the hospital.

DAVID SHIELDS: Claire was an echo of eighteen-year-old Oona O’Neill a decade earlier and a pre-echo of Yale freshman Joyce Maynard two decades later. Salinger’s sexual and romantic imagination circled obsessively around the same, usually dark-haired, boyishly built, gamine figure, from Miriam to Doris, Sylvia, Jean Miller, and onward. He was also repeating the Oona-Chaplin-Salinger triangle.

Claire was already entwined with Mockler, who was newly and deeply involved with fundamentalist Christianity. She and Mocker spent the summer together in Europe. When she returned in mid-September, Salinger wouldn’t take her calls.

SHANE SALERNO: In an undated 1953 letter he informs Jean Miller that his recently published collection of stories, Nine Stories, is “selling very well, but I won’t get any of the money till September.” (The book reached the top spot on the New York Times bestseller list and was on the list for fifteen weeks.) In subsequent letters to her, he begins to discuss Eastern philosophy.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, 1953:

The word is Ko-an, or just Koan. And a Koan is an intellectually insoluble problem given to Zen monks by their masters. I was just telling you a few of them as they came to my mind.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, April 30, 1953:

I’ve had two invitations for dinner this weekend from local people. I’ve lied and said I’m going to Boston. I suppose I’ll have to go now. Damn people.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, 1954:

About those two books I sent you. The little archery book isn’t an orthodox Zen text or anything like that, but it’s nice—the Zen is pure. And besides the beauty of Zen is constantly absorbed in the fact that Zen is where you find it.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, 1954:

I know it’s worrying some of my friends, especially the ones who like my fiction. I think some of them guess that I may turn into a really monastic type sooner or later, give up my fiction, never marry, etc. Nothing is further from my mind at this point. What a low and specious thing “religion” would be if it were to lead me to negate art, love.

DAVID SHIELDS: Following Mockler’s many visits to Claire at the hospital, he proposed marriage to her and—in the wake of Salinger’s silence—she accepted, but in the summer of 1954 Salinger visited her; she was reading The Way of a Pilgrim. Salinger drew her away from Mockler and his Christian fundamentalism via Vedanta, the Hindu philosophy that was overtaking Salinger’s life. Claire soon divorced Mockler. Four months shy of graduation from Radcliffe, she was forced by Salinger to choose between him and a college degree.

SHANE SALERNO: Claire’s feeling for Salinger remained strong, and after breaking off the marriage to Mockler, Claire moved in with Salinger. They married on February 17, 1955, in Barnard, Vermont. Salinger and Claire drove through sleet on a bleak February day to get married by a justice of the peace. On the marriage certificate Salinger said this was his first marriage, completely removing any legal trace of his first wife, Sylvia Welter.

Jerome D. Salinger and Claire Douglas’s marriage certificate.

JOHN SKOW: Uncharacteristically, Salinger threw a party to celebrate his marriage. It was attended by his mother, his sister (about whom little is known except that she is a dress buyer at Bloomingdale’s and has been divorced twice). Claire’s first husband was also present. A little later, at the Cornish town meeting, pranksters elected Salinger Town Hargreave—an honorary office unseriously given to the most recently married man; he is supposed to round up pigs whenever they get loose. Salinger was unamused.

PAUL ALEXANDER: Salinger’s wedding present to Claire was the manuscript of “Franny”; Franny appears to be based on Claire, and it’s not difficult to see Salinger’s portrait of Franny’s painfully conventional boyfriend, Lane Coutell, as being none-too-subtle mockery of Mockler.

—

BEN YAGODA: Salinger’s long story “Franny,” published in 1955, created a sensation. People were talking about it all across the country—the characters, the situations, and especially what had happened to make the main character Franny faint. Was it an existential crisis, or was she pregnant?

JOHN WENKE: When he wrote “Franny” I think Salinger really still wanted to be a popular writer. On the one hand, it was very chic at that time to be a falling-apart rich girl who is having a religious crisis, and I think that became a culturally revolutionary act in the mid-fifties, particularly with the more sanitized Eisenhower administration modality.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Gus Lobrano, New Yorker editor, December 20, 1955:

I’ve been putting this off and putting this off. Mostly because of the Nineteenth Floor criticism that Franny might be pregnant—it seemed to me such a deadly idea, if it was the main one that the reader came away with.

DAVID SHIELDS: Many New Yorker readers thought Franny was pregnant. “She held that tense, almost fetal position for a suspensory moment—then broke down.” If pregnancy is not the main idea here, what is? That Franny, a mythological female, is suffering a postwar nervous breakdown? The mystic’s confused searching for meaning is fulfilled through the use of young girls’ bodies. The womb is the reincarnated war wound. Franny is prayerful witness to the necessity of her creator’s war survival.

MAXWELL GEISMAR: As in any good Scott Fitzgerald tale, it is the weekend of the Yale game. . . . In his Burberry raincoat, Lane Coutell is reading Franny’s passionate love letter. . . . Franny, listening to him “with a special semblance of absorption,” is overcome by her distaste for his vanity, his complacency. It is not only him, it is his whole life of habits, values, standards that she cannot bear. She ends up not only with an indictment of upper-class American society, but almost all of Western culture itself.

J. D. SALINGER (“Franny,” The New Yorker, January 29, 1955):

Lane had sampled his [martini], then sat back and briefly looked around the room with an almost palpable sense of well-being at finding himself (he must have been sure no one could dispute) in the right place with an unimpeachably right-looking girl—a girl who was not only extraordinarily pretty but, so much the better, not too categorically cashmere sweater and flannel skirt.

PAUL LEVINE: Alienated from her Ivy League boyfriend and everything he represents, she turns inward, with the help of a mystical book about a Russian peasant who found God [in tune] with his heart beat when he repeated the “Christ prayer” over and over. Suffering from psychosomatic cramps induced by an environment she can no longer stomach, Franny rejects the comfort of a public restaurant for the awkward privacy of a lavatory, where, in a curiously fetal position, she can pray.

PAUL ALEXANDER: “Franny” is an indictment (as is, of course, Catcher in the Rye). What Salinger is attacking is not specific, but general, even societal. Franny hates insincere people and phonies, yet she is forced to deal with them at college. Even worse, she’s dating one, and for that she has no one to blame but herself, maybe, although in the course of the story she never accepts responsibility for her failure to break up with him. Instead, “Franny” seems to imply that because the world is full of phonies, all one can do is retreat from it into some form of religion. In Franny’s case, she seeks solace in the Jesus Prayer. Ultimately, however, even religion is not enough. As she tries to cope with her life by clinging to religion, she slips deeper into mental distress, until she is barely able to hold on to her sanity. In Catcher in the Rye, Holden ends up in a mental institution. Franny ends up in an unfamiliar room, babbling a prayer to herself, unsure of where she is and where she is going next.

JAMES LUNDQUIST: The Way of a Pilgrim and the Jesus Prayer are by no means being put forth as answers to anything by Salinger. . . . A major idea in Zen . . . is that people who are too critical of others, who are too concerned with the analysis of particulars, fail to reach an understanding of the oneness of all things, and eventually disintegrate themselves.

THE WAY OF A PILGRIM: We must pray unceasingly, always and in all places . . . not only when we are awake, but even while we are asleep.

JOHN WENKE: It’s a hunger that Franny, for example, feels and responds to with the Jesus Prayer. It’s not so much the prayer; it’s the desire for something that will fill that hole. And Salinger’s characters are people who have holes that can’t be filled.

THE JESUS PRAYER: Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me.

SHANE SALERNO: There was so much goodwill built up for Salinger after Catcher and Nine Stories that he was once again seen to be leading the culture, years ahead of the Beats and early Zen adopters. He had once again caught the moment before the moment arrived, but he was in deeper trouble than he realized. At the time, he didn’t think he was undergoing a crisis, but he was—a marital crisis and an artistic crisis and a religious crisis. Years later Salinger would thank his spiritual guide Swami Vivekananda for getting him through this “long dark night.”

—

HENRY GRUNWALD: Stories about his wife [Claire] are even rarer and equally cherished as collector’s items. There is, for instance, the occasion when Salinger was meeting an English publisher at the Stork Club, and Claire and a friend sat at a nearby table, pretending to be tarts. Or the time, after “Franny” was published, when friends would come upon Salinger and Claire, their lips moving silently. It was a private charade—an acting out of the near-final lines in the story: “Her lips began to move, forming soundless words.”

SHANE SALERNO: Salinger and Claire set about building a life for themselves in step with the purity of their religious beliefs and independent of the conventional 1950s obsession with status and appearance. It was a life of simplicity, with an emphasis on nature and spirituality. The couple vowed to respect all living things and, according to Gavin Douglas, Claire’s brother, refused to kill even the tiniest of insects. Their afternoons were filled with meditation and yoga; at night, they snuggled together and read The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna and Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi. From the beginning of their marriage, Salinger worried that Claire would be unable to adapt to the solitude and simplicity of life in Cornish.

ARTHUR J. PAIS: Claire Salinger was attracted to Yogananda’s thinking, too, and got into Kriya yoga. A greater hero for the couple was Lahiri Mahasaya, Yogananda’s guru, who was a married man, proving that yogic attainments could be open to family men and women.

PARAMAHANSA YOGANANDA: You have been chosen to bring spiritual solace through Kriya Yoga to numerous earnest seekers. The millions who are encumbered by family ties and heavy worldly duties will take new heart from you, a householder like themselves. You should guide them to understand that the highest yogic achievements are not barred to the family man. . . .

No necessity compels you to leave this world, for inwardly you have already sundered its every karmic tie. Not of this world, you must yet be in it.

“My son,” Babaji said, embracing me, “your role in this incarnation must be played before the gaze of the multitude. Prenatally blessed by many lives of lonely meditation, you must now mingle in the world of men.”

DAVID SHIELDS: Margaret Salinger credited Lahiri Mahasaya’s advice for giving her father and mother the approval needed to go ahead not only with the marriage but the birth of their daughter.

CLAIRE DOUGLAS: On the train home to Cornish that evening [after seeing a yogi in Washington, D.C., in early 1955], Jerry and I made love in our sleeper car. . . . I’m certain I became pregnant with [Margaret] that night.

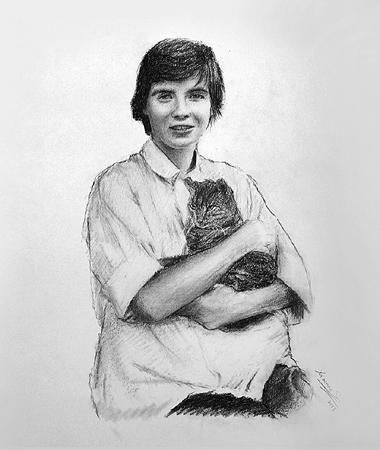

Drawing of Claire, pregnant.

PAUL ALEXANDER: On December 10, 1955, J. D. Salinger became a father. His daughter, Margaret, was born. It was obviously an ecstatic event for Salinger, the birth of his first child. But, ironically, the way he viewed Claire changed after that. Before that, she had been very much the image of the late teens, early twenties woman he was initially fascinated by. Now she was a mature woman. She was the mother of his child. And so, while he was still attracted to her, because she had given him this great gift, his view of her changed, and the birth of the child had a permanent effect on their relationship.

Claire was a smart, attractive, and—one would assume—energetic woman who had come from a proper family in England. She had attended Radcliffe. She was a woman who was connected to the world. And because of the routine of Salinger’s writing life, that ended.

THE GOSPEL OF SRI RAMAKRISHNA: A man may live in a mountain cave, smear his body with ashes, observe fasts, and practice austere discipline, but if his mind dwells on worldly objects, on “woman and gold,” I say, “Shame on him!” But I say that a man is blessed indeed who eats, drinks, and roams about, but who keeps his mind from “woman and gold.”

[In response to a disciple who was still having sex with his wife,] Ramakrishna says, “Aren’t you ashamed of yourself? You have children, and still you enjoy intercourse with your wife. Don’t you hate yourself for thus leading an animal life? Don’t you hate yourself for dallying with a body which contains only blood, phlegm, filth, and excreta?”

CLAIRE DOUGLAS: We did not make love very often. The body was evil.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Swami Nikhilananda, 1972:

Between extreme indifference to the body and the most extreme and zealous attention to it (Hatha Yoga), there seems to be no useful middle ground whatever, and that seems to me one more unnecessary sadness in Maya.

SHANE SALERNO: During this time, the mid-1950s, Salinger met and developed a close relationship with one of his neighbors, Judge Learned Hand, who was Margaret Salinger’s godfather and whom the New York Times has said “belongs with John Marshall, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Louis Brandeis and Benjamin Cardozo: among the eminences of the American judiciary.” Often called the “tenth justice of the Supreme Court,” he was viewed by Salinger as a “true Karma Yogi.” Salinger’s description here conveys how deeply involved he now was with the language and vision of Vedanta. In a letter to Hand, Salinger wonders “whether I’m still [plying] my trade as a short story writer or whether I’ve gone over to propagandizing for the loin-cloth group.”

To make matters worse for Claire, Salinger was absorbed by his work throughout the first year of their marriage. He frequently took trips to New York City, where he would hole up in the New Yorker offices and work. S. J. Perelman, the New Yorker humorist who’d gotten to know Salinger as a colleague at the magazine, visited him often in Cornish.

LEILA HADLEY LUCE: Sid [S. J. Perelman] said, “It’s very strange: he’s got this concrete bunker where he works, but he’s got a great big statue of Buddha in the garden, and he’s got a lot of these Buddhist priests around him.” Sid thought [Claire] was just a collegiate type of girl.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Jean Miller, 1954:

The house was very still when I got here, and I sat down and thought for hours. In the end, it seemed to me that if I’m to get my work done, if I’m to do my “duty” (a word I hate) properly—that is, more or less in the Bhagavad Gita sense of the word—I ought to and must stay away from the city.

—

SHANE SALERNO: Claire must have dreamed about a life with Salinger and a family in the quiet woods of New Hampshire, but she quickly learned that he already had a family: the Glasses.

SANFORD GOLDSTEIN: You’ve got this very, very bright family, the Glass family. It’s a very concentrated picture of troubled humanity and we want to know them. We want them to get beyond their problems; we want to learn from them.

GERALDINE McGOWAN: One of the odd things about comparing real children to the Glass children is nobody would want their children to be the Glass children. They’re all suffering terribly. They’re all in a lot of pain most of the time. Salinger’s real children may have thought their father preferred the Glass children. That is part of the dysfunctional quality associated with Salinger, because if you loved your children, why would you ever wish upon them that life?

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Paul Fitzgerald, February 3, 1960:

We have a second child due very shortly, and I’ve been working overtime to beat the clock. You must have a pretty good idea by now how little peace there is around the house when a new baby is around. And I agree with you about old friendships. Especially war ones.

ETHEL NELSON: When I started taking care of his kids, it was through Wayne, my husband, because he was already working for Jerry down there. Claire was due to have Matthew and they had a little girl, Margaret. They needed help keeping Margaret busy so that Claire could do what she had to do. Jerry knew me from back when he hung out with me and my friends in the Windsor High School days, so the hiring process was pretty simple.

My job was to take care of Margaret, who we called Peggy. She was about four or five years old at the time and a sweet girl, very sweet. And Jerry, I knew he was around, but I never saw him because he was down [the hill], working on his books, and just didn’t come up around the house at all. I really don’t know if the children got to know him very much in the early years. I’ve seen some pictures where he carried Peggy around, but how many times did that happen?

The house was a cute house, kind of like a dollhouse, right near the road and with a big fence for protection. I think there were a few flowers out front. Claire attempted to make a garden and have everything look nice, but it was not friendly soil. It hadn’t been worked up or fed for years and years. The land was very rustic, with lots of woods around and fields. Behind the house you had a deep incline, which is where Jerry built the other building so he could write down there.

It wasn’t a house; it was just a small building. I would think of it like a dynamite house. That’s where he would go down, anytime, day or night, go in and shut the door, and you wouldn’t see him for a week or longer, because he got into a writing mode and had to be left totally alone. I don’t think it was much more than a room, room and a half, his writing building.

Wayne cleared brush, cut down trees that were bothersome, mowed the lawns, did gardener types of things. Wayne would go down and work around the woods and kept the path cleared between the house and the writing building.

I never went down there. Wayne did one day; he was out there working, and Jerry went to the door and asked him if he wanted something cold to drink. Wayne sat down and chatted with Jerry, which I know today is a very rare thing. They just got to talking, and Jerry asked Wayne if he’d like an autographed copy of The Catcher in the Rye. And Wayne said, “No, that’s all right, Jerry, but thank you. I don’t read all that much.” My husband was just a farm boy; he didn’t think too much about it. I guess that signed copy would be worth quite a bit of money today. Wayne told me there was quite a mess of papers down there. I guess all authors have a mess of papers, but I don’t know any other authors.

When I was working for Claire, I very seldom ever saw Jerry. I would go in and straighten up the kitchen and talk with Margaret, and Matthew being the baby, I didn’t have to do too much with him. That’s where Claire was busy. I never fixed a meal. Claire was great at that sort of thing. She was a good cook. I just cleaned up, played with Margaret, and went home.

I’d get there at eight-thirty. If there were dishes around, I’d do them up. Usually Peggy was still with Mom and in the other room, and then she would come out and I’d have the housework part done. We went out for walks, not too far. Jerry wouldn’t allow you to go too far, so we’d go out on the side of the house and we’d pick flowers and bring them into Mom, or Margaret would get up on a stool and help me with the dishes. Or we would get things out for her to color. We spent a lot of time just chatting together. Peggy was a neat kid. I could keep her busier by being outside, walking and looking at flowers and talking about things outside that way. But you know, three- or four-year-olds, you can’t talk a whole lot to them about stuff.

She was happy; Margaret was always very happy. Always had that big smile. I don’t recall anyone having to speak to her more than once, so she was being brought up well to listen when things were said. I think she really needed a friend young in life. You always picture those kinds of kids as being brought up happy. I just hate to think of children growing up so lonely, so alone. I don’t think they ever really knew a home life, and I feel sorry for that. Every child needs a home life.

At the time I was there, I don’t think Peggy was affected that much with [the solitude]. She was only three and four years old. I think as she got to be eight, nine, and ten, it affected her a lot. By that time, Jerry had also put that apartment over the garage, and that’s where he sat and wrote “Raise High the Roof Beam.” If he was in either of those places, the kids weren’t allowed to get near him. Neither was his wife. You kind of fantasize that if people have money, they have happiness. It’s not so.

Claire impressed me greatly for putting up with so destitute of a husband. He was just never there, and she’s just the kind of a lady you imagine with a long dress and a neat hairdo and a glass of wine in her hand, talking with lots of New York people. Well, that’s how she always appeared to me. Her role just didn’t seem right.

GERALDINE McGOWAN: Claire was very young, but Salinger always treated women like they were unbreakable. He has this idea that little girls especially can be leaned on by adult males. It’s a bizarre, bizarre thing to think. But he does, and in the fiction it’s almost like he’s writing an urban Heidi or an urban Pollyanna. These little girls, who come in and save the world, don’t need any help from anybody, no matter what they’ve suffered. It’s a fairy tale, of sorts. Women have a fairy-tale quality in his work.

Esmé has lost both her parents, but she helps Sergeant X. Zooey says some of the nastiest things in the world to his mother, Bessie; she never blinks, just worries about Franny. Women don’t break, in [Salinger’s] view; they’re always just there to support these very sensitive men. I don’t think he thought much about Claire. I think this image of women was so strong within him, he didn’t think there was any reason for him to worry about Claire, whereas, of course, any woman alone—with a baby at the age of twenty, no family, no friends—would need help. That did not seem to occur to him.

—

BEN YAGODA: In that period, 1955, Salinger was clearly concentrating on this family he had invented, the Glass family. “Franny” was quickly followed by “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters,” a wonderful novella about members of that same family.

BRUCE MUELLER and WILL HOCHMAN: The importance of “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters” within Salinger’s body of work cannot be overstated. This 1955 story assembles and introduces the Glass family in its entirety and may be considered a watershed event in Salinger’s publication history.

DAVID SHIELDS: It’s as if he is pulling an immense blanket over himself: from now on he will keep himself warm by the heat of this impossibly idealized, suicidal, genius, alternative family. This will become his mission: to disappear into the Glasses.

JAMES LUNDQUIST: [“Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters”] centers on sacrament and celebration, although ironically at first. It deals with Seymour’s wedding to Muriel, but Seymour does not appear, and Buddy, the only member of the Glass family who is able to be present for the ceremony, is forced into a car with four other wedding guests to be driven to the apartment of the bride’s parents for what has turned out to be a non-wedding reception. The situation Salinger utilizes to build his story around is a classic one in vaudeville and burlesque humor.

JOHN UPDIKE: [It is the] best of the Glass pieces: a magic and hilarious prose-poem with an enchanting end effect of mysterious clarity.

EBERHARD ALSEN: Seymour is presented as both highly educated and mentally unstable. The story is told by Seymour’s brother Buddy, and Seymour’s character emerges from Buddy’s conflict with the irate wedding guests and from his attempts to understand Seymour’s unstable behavior. These attempts include lengthy quotations from Seymour’s diary, which contains many references to Eastern religions, chiefly classical Taoism and Vedanta Hinduism.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Swami Adiswarananda, 1975:

I read a bit from the [Bhagavad] Gita every morning before I get out of bed.

LESLIE EPSTEIN: What a triumph “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters” is. It’s a magnificent story and a perfect counterweight to “Bananafish.”

SHANE SALERNO: In “Franny” and “Raise High,” both published in 1955, Salinger still had the balance about right: 80 percent story and character, 20 percent religion and lecture.

J. D. SALINGER (“Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters,” The New Yorker, November 19, 1955):

“We were up at the Lake. Seymour had written to Charlotte, inviting her to come up and visit us, and her mother finally let her. What happened was, she sat down in the middle of our driveway one morning to pet Boo Boo’s cat, and Seymour threw a stone at her. He was twelve. That’s all there was to it. He threw it at her because she looked so beautiful sitting there in the middle of the driveway with Boo Boo’s cat. Everybody knew that, for God’s sake—me, Charlotte, Boo Boo, Waker, Walt, the whole family.” I stared at the pewter ashtray on the coffee table. “Charlotte never said a word to him about it. Not a word.” I looked up at my guest, rather expecting him to dispute me, to call me a liar. I am a liar, of course. Charlotte never did understand why Seymour threw that stone at her.

DAVID SHIELDS: In her book, Margaret Salinger says she doesn’t understand why Seymour throws the rock at Charlotte, but it’s clearly meant as a parable: the young, beautiful Charlotte was too beautiful to remain undamaged in this world. Margaret, having lived with Salinger, doesn’t believe in damage as revelation. This, though, is Salinger’s major chord. Seymour never appears in the story except when Buddy reads his diary or characters describe his actions, all of which occur off the page as ritualized funeral ablutions, washing the body in preparation for its spiritualized reincarnation in thousands of future dead GIs and Jews. Seymour writes that he told his fiancée, Muriel, that a Zen Buddhist master answered the question “What is the most valuable thing in the world?” with the answer “a dead cat was, because no one could put a price on it.” Seymour tells Muriel’s mother that the war seems likely to go on forever, but if he is ever released from the army he would like to return to civilian life as a dead cat.

IHAB HASSAN: In the story of his wedding and the record of his buried life Salinger has exercised his powers of spiritual severity and formal resourcefulness to their limit, and it is indicative of Salinger’s recent predicament that in the story the powers of spirit overreach the resources of form. He is seeking, beyond poetry, beyond all speech, the act which makes communion possible. As action may turn to silence, so may satire turn to praise.

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Salinger kills Seymour—his chief protagonist of several works—in one of the early stories [“A Perfect Day for Bananafish”]. In the later works, the novelist proceeds with dexterous artistry to re-create and rebuild all those circumstances and reasons responsible for his hero’s tragic end. This enables the novelist to construct a corpus of investigation on which he slowly but surely goes to delineate his concept of man. In doing so, a visibly perceptive change comes in the form and the structure of the later works when it becomes clear that the thematic interest triumphs over the fictional interest.

PHILIP ROTH: He has learned to live in this world—but how? By not living in it. By kissing the soles of little girls’ feet and throwing rocks at the head of his sweetheart. He is a saint, clearly. But since madness is undesirable and sainthood, for most of us, out of the question, the problem of how to live in this world is by no means answered; unless the answer is that one cannot.

—

DAVID SHIELDS: There was the Salinger family and the Glass family, but there was also a third family: the New Yorker, with William Shawn as patriarch. In contemporary parlance, he was Salinger’s enabler: he encouraged Salinger’s best tendencies (his devotion to literary art) but also his worst tendencies (toward recusal, toward retreat, toward isolation, renunciation, purity, inscape, even silence). Salinger found an artistic, neurotic soul mate in Shawn; while he reaped the artistic benefits that resulted, Claire and their children were left to fend for themselves in the hermetic Cornish paradise Salinger had built for himself, not for others.

ROGER ANGELL: When he first came to the [New Yorker], Salinger worked with Gus Lobrano [and William Maxwell], but William Shawn took over [after Lobrano’s death]. . . .When I came to the fiction department, none of the editors in the department dealt with Salinger—only Shawn.

BEN YAGODA: What elevated Shawn professionally was World War II. Shawn used the war to transform the magazine from a sophisticated humor magazine into a magazine that published serious journalism, culminating in the publication of John Hershey’s “Hiroshima,” which occupied one entire issue. It was shepherded by Shawn. He was the one who germinated the idea with Hershey, argued it should take up the entire issue, edited it, and brought it into print. That elevated Shawn in the halls of the New Yorker and in the literary world.

THOMAS KUNKEL: Shawn always wanted to be a writer, and because of that, he just understood the writer’s psyche in a way that few people ever have. He understood what they were trying to do and how hard it is, but also knew how it could be put into print.

A. SCOTT BERG: Shawn didn’t want to be seen or known about, wanted to print his authors rather selflessly, and knew that often the time that an author needs an editor most is not when the book is all done but while he’s actually writing it. Shawn was the presence on Salinger’s shoulder.

VED MEHTA: Shawn got involved in every little thing at the New Yorker. J. D. Salinger wrote about this family of geniuses. In a way, the atmosphere at the New Yorker was that of an extended Salinger family. Mr. Shawn really didn’t want to be a wise father; he was like a wise brother on the nineteenth floor. You consulted him on anything and everything. If you needed a psychoanalyst, you would ask Shawn.

Shawn never gossiped. If you said something to him, it was like shouting it in a tomb. There was never this worry, “Oh God, people will know that a third of my piece had to be cut because it was badly written.” It was all so secret. After all, he was the most private man I’ve known, except maybe for J. D. Salinger.

LAWRENCE WESCHLER: Imagine the most phobic man in the world. He lives in a city surrounded on all sides by water, and he is afraid of everything—bridges, tunnels, buses, limousines, helicopters, planes, ferries. He cannot bring himself to get off that island, but he is also the most curious man in the world. He wants to know about everything and everyone and every place. And now imagine that by some fluke this man has come into what amounts to limitless wealth: he can take people and train them as his surrogates and then send them forth. “Go,” he tells them. “Go—take however long you need, but then write me back what it is like there, what the people are saying and feeling, how they spend their lives, what they worry about—write me all that, make it complete, and make it vivid, as vivid as if I’d been able to go there myself.” And each week he puts together a folio of their letters, of their reports, and he produces a little private magazine, just for himself. And everybody else gets to read over his shoulder (he doesn’t mind, but he hardly notices). That’s what it’s like to work for William Shawn. He really is the New Yorker.

ROBERT BOYNTON: Beyond what he accomplished as an actual editor, Shawn was important because of the cult of personality that arose around him.

THOMAS KUNKEL: Shawn was a person of very set routines. He edited only with certain kinds of pencils. He did have a lot of idiosyncrasies, but that was part and parcel of the person, and I think one of the reasons that writers responded to him so well was that the insecurities and phobias actually humanized him a little bit.

PAUL ALEXANDER: Shawn would go to lunch every day at the Algonquin and order Corn Flakes.

BEN YAGODA: In the summer, Shawn wore wool suits and sweaters and overcoats. He left the state of New York only once in the last fifty years of his life, to visit his family in Chicago. He was introverted and never gave interviews. His whole life was wrapped up in the New Yorker and his writers until the end of his life. Two employees were outside his office to prevent people from walking in unexpectedly.

TOM WOLFE: Shawn went to work at the New Yorker building on Forty-third Street with an attaché case. As soon as he entered the building, an elevator operator would put a hand across the elevator entrance so nobody else could get in. They’d ride Shawn up to his office. Inside the attaché case was a hatchet. In case he got stuck between floors he would be able to chop his way out. Good way to get killed. That was Shawn’s personality.

THOMAS KUNKEL: It was very much the New Yorker’s editing style to be obsessive in a lot of different ways. The editors—Shawn principally among them—were equally passionate about where the commas should go and whether this warrants a dash or not. A writer would get to the point where he was answering countless questions; there were iterations and iterations and iterations of galleys.

A final proofreader found a spot that he felt needed a comma. He went to Maxwell, who looked at it and said, “Well, it looks like it needs a comma to me.” They couldn’t find Salinger, so they went ahead and put the comma in. When the story came out, Maxwell said Salinger was melancholy about that comma and never forgot it. Maxwell said, “I never again introduced another piece of punctuation into a Salinger story without talking to him.”

BEN YAGODA: It’s hard to know much about the precise nature of the collaboration between Salinger and Shawn because, let’s face it, we’re dealing with two of the most private men in the history of literature, if not the world. But we do know that when Salinger submitted “Zooey,” the sequel to “Franny,” to the New Yorker in 1957, the fiction editors unanimously agreed to reject the story.

When I interviewed William Maxwell, who was one of the editors, he said the reason was that the New Yorker didn’t publish sequels, but they had before. I think he was being tactful. I think they just didn’t like the story.

DAVID SHIELDS: The New Yorker was trying to tell Salinger not to throw over art for religion, but he didn’t listen. Why should he? The New Yorker had rejected Catcher. So, too, on November 18, ’57, Time said, “The one new American author who has something approaching universal appeal is J. D. Salinger.”

BEN YAGODA: Shawn intervened. He was the editor in chief, and he decreed that the magazine would publish the story; he edited the story and worked with Salinger on it.

In a 1959 letter, William Maxwell wrote to Katherine White [fiction editor], who had retired, alluding to the earlier Salinger incident. Maxwell wrote, “I do feel that Salinger has to be handled specially and fast, and think that the only practical way of doing this is as I supposed Shawn did do it: by himself. Given the length of the stories, I mean, and the Zen Buddhist nature of them, and what happened with ‘Zooey.’ ”

—

DAVID SHIELDS: “Zooey,” a 50,000 word sequel to “Franny,” takes place two days after Franny has returned from her date with Lane. While she’s in the living room in the Glass family apartment in New York, having a breakdown, her brother Zooey is taking a long bath and reading a long letter from their brother Buddy; his mother, Bessie, barges in, wanting to talk with him about Franny. A large percentage of the story occurs in that bathroom while Zooey and Bessie talk and smoke.

JOHN WENKE: The action of “Zooey” picks up two days after Franny has fainted at Sickler’s restaurant. It is Monday morning at the Glass family’s Manhattan apartment. Franny’s breakdown continues, and Mrs. Glass does not know what to do. . . . Zooey seems, in Bessie’s view, to be the only one available who might be capable of helping Franny get beyond her exasperating and frightening behavior. . . . [The story] resembles a one-act play of three scenes in which the players transact their business almost solely through dialogue.

MAXWELL GEISMAR: “Zooey” is an interminable, appallingly bad story. Like the latter part of “Franny,” it lends itself so easily to burlesque that one wonders what the New Yorker wits were thinking of when they published it with such fanfare.

MICHAEL SILVERBLATT: I was looking at “Zooey,” and there we are in that bathroom, right? Forty pages of someone in a bathroom being bothered by his mom. We want to get out of this bathroom. Why can’t we get out of this bathroom? Why won’t Salinger let us out? It’s so imprisoning, so claustrophobic. It’s not Kafka-claustrophobic or Beckett-claustrophobic. It’s boring-claustrophobic. Bathroom claustrophobic. I’m thinking, “Let’s get out, face the world, get to business.” I think that [claustrophobia] is the state a writer is in at his desk. He is asking you to experience being in that bathroom, unable to leave, the way a writer experiences being at the desk, unable to leave.

DAVID SHIELDS: “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters” comes close to structural perfection, whereas the problem with “Zooey,” and why it took Salinger so long to write it, is that he is blatantly pontificating about religion, which he was criticized for having done in previous stories. Increasingly, he is determined to present his religious beliefs through his stories.

PHOEBE HOBAN: It’s interesting that Salinger uses letters so much in his books. One of the reasons he does that is that, for Salinger, writing is the most perfect form of communication; almost all of his stories have a pivotal letter in them. He begins “Zooey” with a four-year-old letter from Buddy that Zooey’s reading in the bathtub and gaining wisdom from so that he can then tell Franny how to get through her breakdown.

DONALD COSTELLO: “Franny” and “Zooey” speak to one another: they’re separate yet nicely joined. Franny’s sick of ego. “Ego, ego, ego!” she says. She finds a mystical connection with the Jesus Prayer. It’s also very Buddhist, of course, in its philosophy of withdrawal. Zooey, on the other hand, argues, as Mr. Antolini does, and as Holden allows Phoebe to do at the end [of Catcher in the Rye], for engagement.

ERNEST HAVEMANN: Near the end of the new book, Zooey tells his sister [Franny] about the time that Seymour urged him to shine his shoes before appearing on the [radio quiz program It’s a Wise Child]. Zooey objected that nobody could see his shoes, but Seymour insisted: “He said to shine them for the Fat Lady. . . . He never did tell me who the Fat Lady was, but I shined my shoes for the Fat Lady every time I ever went on the air again. . . . This terribly clear, clear picture of the Fat Lady formed in my mind. I had her sitting on this porch all day, swatting flies. . . . I figured the heat was terrible, and she probably had cancer. . . .” Then Zooey goes on to say, “There isn’t anyone anywhere that isn’t Seymour’s Fat Lady. . . . And don’t you know—listen to me, now—don’t you know who that Fat Lady really is? . . . It’s Christ Himself, Christ Himself. . . .” And upon hearing these words, Franny, who has been having the symptoms of a nervous breakdown in connection with her religious strivings, relaxes and falls into a deep and soul-satisfying sleep, and the story is over.

ALFRED KAZIN: In each story [“Franny” and “Zooey”], the climax bears a burden of meaning that it would not have to bear in a novel; besides being stagey, the stories are exalted in a way that connects both of them into a single chronicle. . . . Both Franny and Zooey Glass are, indeed, pilgrims seeking their way in a society typified by the Fat Lady. Not only does the entertaining surface of Franny and Zooey depend on the conscious appealingness and youthfulness and generosity and sensitivity of Seymour’s brother and sister, but Salinger himself, in describing these two, so obviously feels such boundless affection for them that you finally get the sense of all these child prodigies and child entertainers being tied round and round with the veils of self-love in a culture which they—and Salinger—just despise.

S. J. ROWLAND: The cumulative effect is bright and tender rather than powerful, and poignant rather than deep: these are the strengths and limitations of Salinger as a writer. These granted, he has an almost Pauline understanding of the necessity, nature, and redemptive quality of love.

VED MEHTA: Salinger was the first one, at least in my consciousness, to put his finger on the fakery; to be an enlightened person, to be a good person, you had to avoid phoniness. You had to avoid all this fakery even if that made you become very solitary and cut off. At the same time—I’ll never forget—there is the wonderful scene about loving a fat lady, which was, in a way, the unconscious New Yorker principle: you didn’t reject people because they were fat or they were ugly; each human being had to be prized as him- or herself. I think it was very much the New Yorker ethos, a Shawn ethos, and I have no idea, actually, whether Salinger got that from Shawn or Shawn got that from Salinger.

STEPHEN GUIRGIS: When I started writing my play Jesus Hopped the A Train, I wrestled with the idea of God. I was stuck, and I read Franny and Zooey. It just blew me away. I’m still writing about religion, still trying to figure out how to get by in this life. Salinger’s explanation at the end of that book is as good as any I have to go on.

—

PAUL ALEXANDER: During 1958, Salinger had begun work on “Seymour: An Introduction,” yet another novella about the Glass family, and the densest thing he had ever written. As a result, he found work on “Seymour” to be unusually difficult, much more so than anything he had written up until then. Throughout the fall of 1958, his work in Cornish was hampered by minor illnesses and the unavoidable distractions caused by Claire and the baby. Finally, in the spring of 1959, Salinger realized that if he were going to finish the novella, which the New Yorker was pressuring him to do, he needed to have a stretch of time during which he could focus only on his work. So he went to New York to work in the New Yorker offices, something writers did when they needed to devote large blocks of intense, uninterrupted work to a piece of prose. He had tried writing several days in an Atlantic City hotel room, but he had not been able to accomplish what he had hoped to.

PHOEBE HOBAN: In letters, he reported that his work habits were hard on Claire—and on himself. He worked so feverishly on one story that he got shingles. Working on the Glasses, he wrote, put him in a constant “trance.”

NEW YORKER INTERN: He was in New York, working on “Seymour.” He’d come up to the office at night and there’d be just the two of us in this big dark building. He was working seven days a week and it was the hardest work I’ve ever seen anyone do.

PAUL ALEXANDER: Eventually, Salinger worked so hard he made himself sick. Returning to Cornish, he stayed there long enough to get well; then he went back to New York for another several-days-long editing session in the New Yorker offices to finish the piece.

BEN YAGODA: The turning point with Salinger and the New Yorker and the Glass family came in 1957, with the publication of “Zooey,” which wasn’t as immediately accessible as the previous works. “Seymour: An Introduction” intensified this sense that he was getting more remote from readers. It added to the sense that Salinger was growing more wrapped up in his own world. Not that he didn’t still have ardent fans. There were still many people who snapped it up as soon as it came out.

WILLIAM WIEGAND: In “Seymour,” Buddy takes up one at a time the pertinent characteristics and activities of his brother. . . . If I pull myself together, Buddy says, Seymour who has killed himself may yet be reconstructed—his eyes, his nose, his ears may rematerialize, even his words may be heard without the echo of the tomb. . . . Buddy becomes almost indistinguishable from Seymour. Buddy himself notices this. The object-observed has become the observer. All the air has been pumped out of the bell jar. . . . Consequently the description of the relationship is so great an effort that Buddy breaks into a cold sweat or sinks to the floor. . . . He [Seymour] is ephemeral, and no matter how many homely anecdotes are told about him, he has grown too diffuse to look at in the daytime; his talents have become supernatural.

JAMES LUNDQUIST: It is the idea of compromise that Buddy is mulling over at the age of forty when “Seymour: An Introduction” begins. He is speculating about his own career as a writer, a career that at first does seem like a considerable compromise when contrasted to that of Seymour. Buddy is a writer of fiction who must worry about communicating with the “general reader.” . . . The quotations from Kafka and Kierkegaard along with the corresponding implications of Zen art do suggest one thing—that the entire story is a fictional treatise on the artistic process.

GRANVILLE HICKS: Self-consciousness gives the story its peculiar quality, and although the tone is beautifully sustained, as always in Salinger’s later work, the self is exceedingly obtrusive.

JOHN WENKE: At the very outset Buddy Glass confronts the necessary (and intrinsically self-defeating) paradox of his condition. The only way to introduce the late Seymour is to use language; the use of language by nature is doomed to fail.

J. D. SALINGER (“Seymour: An Introduction,” The New Yorker, June 6, 1959):

There are one or two more fragmentary physical-type remarks I’d like to make, but I feel too strongly that my time is up. Also, it’s twenty to seven, and I have a nine-o’clock class. There’s just enough time for a half-hour nap, a shave, and maybe a cool, refreshing blood bath. I have an impulse—more of an old urban reflex than an impulse, thank God—to say something mildly caustic about the twenty-four young ladies, just back from big weekends at Cambridge or Hanover or New Haven, who will be waiting for me in Room 307, but I can’t finish writing a description of Seymour—even a bad description, even one where my ego, my perpetual lust to share top billing with him, is all over the place—without being conscious of the good, the real. This is too grand to be said (so I’m just the man to say it), but I can’t be my brother’s brother for nothing, and I know—not always, but I know—there is no single thing I do that is more important than going into that awful Room 307. There isn’t one girl in there, including the Terrible Miss Zabel, who is not as much my sister as Boo Boo or Franny. They may shine with the misinformation of the ages, but they shine. This thought manages to stun me: There’s no place I’d really rather go right now than into Room 307. Seymour once said that all we do our whole lives is go from one little piece of Holy Ground to the next. Is he never wrong?

MICHAEL WALZER: [Since The Catcher in the Rye] Salinger has written almost entirely of the Glass family, a clan of seven precocious children, of Irish-Jewish stock and distinctly Buddhist tendencies. The main theme of these stories has been love. . . . The family here is a mythical gang, truly fraternal, truly affectionate; it is as if, remembering Holden’s loneliness, Salinger is determined never again to permit one of his characters to be alone.

EBERHARD ALSEN: Salinger’s withdrawal from those who should be closest to him took its first toll in early 1957, while he was finishing “Zooey.” On a trip to New York City, his wife, Claire, suddenly packed up their baby daughter, Margaret, and left him. Supported by her stepfather, Claire and her baby lived in New York City for four months until she gave in to Salinger’s pleading and returned to Cornish.

JOHN C. UNRUE: Early every morning Salinger went to that bunker with his lunch and wrote until late in the evening, giving strict orders that he was not to be disturbed for anything unless the house was burning down. I think Salinger built a bunker because he associated it with impenetrability. He regarded it as a safe place, a good place to write. Whether there were bombs falling, whether there were animals attacking, whatever, it was the place nobody could enter. It was the sacred place for him. It was important for Salinger to have a completely private space and a space that was uniquely his. It was almost a holy spot that no one else should ever come in.

STEPHEN GUIRGIS: I think he’s a guy who went into that bunker and wrote every day. He wrestled with himself and wrestled with demons and wrestled with the muse and tried to make good work. I can’t even imagine the degree of introspection, gut-wrenching, soul-searching discipline, commitment, self-abuse it must have taken to produce some of the work that he produced.

DAVID SHIELDS: It’s hard not to think of the bunker as a way to return to the war, World War II. The bunker would remind Salinger that he should be writing about the most serious matters of existence. The bunker also functions as a fence between yourself and the world. God forbid you might hear a radio from a car passing by or a bird flying overhead. As a writer, you want to be driven by your own aesthetic impulses, but the world has to come in to you, lest you disappear down your own alimentary canal. You have to have the world come in, and then you want to send messages out. It’s supposed to be a two-way communication system.

J. D. SALINGER (“Seymour: An Introduction,” The New Yorker, June 6, 1959):

Yet when I first read that young-widower-and-white-cat verse, back in 1948—or, rather, sat listening to it—I found it very hard to believe that Seymour hadn’t buried at least one wife that nobody in our family knew about. He hadn’t, of course. Not (and first blushes here, if any, will be the reader’s, not mine)—not in this incarnation, at any rate. . . . And while it’s possible that, at odd moments, tormenting or exhilarating, every married man—Seymour, just conceivably, though almost entirely for the sake of argument, not excluded—reflects on how life would be with the little woman out of the picture . . .

PAUL ALEXANDER: Claire and the domestic life she represented were always secondary to his almost maniacal drive to write, to write every day, to write all day long.

There was another problem that developed in the marriage. Salinger became obsessed with eating organic foods prepared only with certain cooking oils. Now you might think that that’s a minor development in one’s life, but when someone is exerting that level of control, controlling what his spouse is allowed to eat, it’s got to have an obvious and profound effect on the relationship.

Eventually, Claire simply couldn’t take it anymore: the isolation, the weird eating habits, the emotional abuse as a result of this isolation. She went to see a doctor in nearby Claremont and complained of restlessness, inability to sleep, loss of weight, all the classic signs of someone who was depressed.

THE GOSPEL OF SRI RAMAKRISHNA: It is “woman and gold” that binds man and robs him of his freedom. It is woman that creates the need for gold. For woman one man becomes the slave of another, and so loses his freedom. Then he cannot act as he likes.

PAUL ALEXANDER: There would be long stretches of time when he wouldn’t come out of the bunker at all. He would stay down there. He put an army cot in there. He put a phone in. It was designed so that he literally never had to leave the bunker. He could stay down there and write, day and night, for days and days and days, eventually weeks on end. And you think about the life [the children’s babysitter Ethel Nelson] saw. Salinger’s family—they were up in one house, living their lives, and here he was, only a few yards away. Secluded, holed up in a bunker. Writing and writing and writing and writing, with clear instructions to Ethel and to Claire and the children not to be disturbed, ever, under any circumstances. What a bizarre existence this was.

DAVID SHIELDS: In 1961, when Margaret was five, she would sometimes walk through the woods to bring her father lunch in his bunker. In his bunker were a cot, a fireplace, and a manual typewriter. Claire and Margaret had reality to contend with, whereas the Glass family could be what his imagination needed them to be, wanted them to be. It was almost inevitable that when there was a competition between the two families that Salinger created, the Glass family would win out in the end.

—

SHANE SALERNO: As director of linguistic studies at Behavioral Research Laboratories in Menlo Park, California, Gordon Lish asked Salinger, among many others, to write an essay for the Job Corps “Why Work” program.

GORDON LISH: In February 1962 the telephone operator at the Behavioral Research Lab said she had a Mr. Salinger on the phone for me, and because of the nature of the laboratory I thought that she was talking about Pierre Salinger, the press secretary to President Kennedy. So I was surprised to discover that it was J. D. Salinger. He started by saying, “You know who I am and you know I don’t reply to telephone calls and mail, and I’m only doing this because you seem to be hysterical or in some sort of difficulty.” That struck me as amazing since the telegram had gone out in the fall sometime and here it was winter. But that was the pretext of his phone call—he said I was in some kind of problem. Then he said, “You only want me to participate in this because I’m famous.” And I said, “No, no, no, it’s because you know how to speak to children.” He said, “No, I can’t. I can’t even speak to my own children.”

I said it was easy to speak to children if you open up your heart to them. After this, we talked for about twenty minutes, chiefly about children. His voice was very deep. Haggard-sounding, weary-sounding. He didn’t sound at all like I expected Salinger to sound. He didn’t sound verbal. He possessed none of the adroitness I would have anticipated. Anyway, he did tell me he never wrote anything if it was not about the Glasses and the Caulfields, adding that he had shelves and shelves filled with the stuff. So I said, “Well, gee, that will be fine. Just give me some of that.” Soon the phone call ended, and, of course, he didn’t agree to provide me with a piece on why he loved his work.

A. E. HOTCHNER: He retreated more and more into a cement bunkhouse and God knows what else, rejecting marriage and other things.