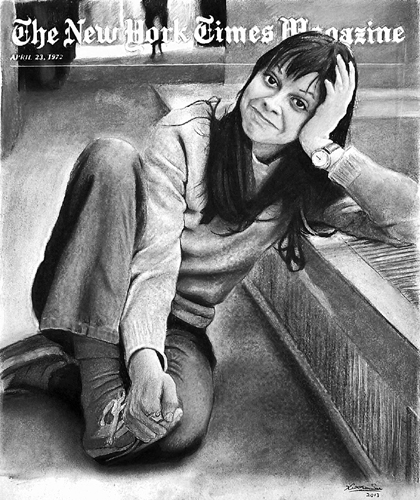

Joyce Maynard is a world-weary eighteen-year-old Yale freshman who becomes famous when, on April 23, 1972, she publishes a New York Times Magazine cover story, “An 18-Year-Old Looks Back on Life,” about what it’s like to be a world-weary eighteen-year-old Yale freshman: “We inherited a previous generation’s hand-me-downs and took in the seams, turned up the hems, to make our new fashions. We took drugs from the college kids and made them a high-school commonplace. We got the Beatles, but not those lovable look-alikes in matching suits with barber cuts and songs that made you want to cry. They came to us like a bad joke—aged, bearded, discordant. And we inherited the Vietnam War just after the crest of the wave—too late to burn draft cards and too early not to be drafted. The boys of 1953—my year—will be the last to go.”

Salinger, fifty-three, who doesn’t believe in author photographs, is captivated by Maynard’s cover photograph and dying-swan syntax. During their nine-month relationship he will wind up telling Maynard, “I couldn’t have created a character as perfect as you.” Maynard will later say, “In his letters he appears to be talking about me. Reading what he has to say now, I see something else. His letters are about himself.” Here, in excerpts from these letters—which were later sold and removed from the public record, but which we have now obtained—is the only self-portrait available of a man who had removed himself from the public eye decades before.

Dear Miss Maynard,

A few unsolicited words in strictest privacy, if you can bear it, from a countryman, of sorts, one who is not only an equally half-and-half and right-handed New Hampshire resident but, even more rare and exciting, perhaps the last active Mousketeer east of the White House. . . . My guess is that you’ll be receiving a pretty interesting-peculiar assortment of letters as a result of this past Sunday’s Times Magazine. In my probably over-earnest way, I ask you to be almost inhumanly cautious about accepting any offers or invitations that come in from anybody and everybody—publishers, editors, Mademoiselle staff people, television talk-show hosts, movie people, etc.

Do, please, watch over your own talent with some realistic (or duly cynical or bitter) awareness that no one else is really fit to do it. I know a little bit about the risks and rather doubtful attractions of early publication.

I think you’re sounder of mind, limb, and psyche than I ever was at eighteen. Better wired. . . . You’re twice the writer and observer at eighteen that I was—ten times, if not more. I was immature, melodramatic, full of self-protective lies, ruses. I wrote and wrote, but badly, really badly. . . . I needn’t have suggested so glumly that you let things build rather slowly. “Fame and success.” No great worry for you because you’re both clever and intelligent, I think. One good mouthful of it and the taste for it alters, drastically or Subtly. Surely “fame” for a practicing writer is mostly comprised of assorted forms of conspicuousness, and nearly all of them, while they last, interruptive and more.

Be determinedly wise.

I feel a need to make it pretty clear to you, first, that I’m not wise, at all, and it would shake me more than a little if you thought I might be. I’m mainly just middleaged, suspicious, untrusting, solipsist—a “dirty Capricornian” some new and valued friend called me at dinner in N.Y. last week, in the same awful boat with Howard Hughes and Richard Nixon.

I’ve spent a great part of my life in grave and increasingly sad doubt about almost every value I’ve ever had a good, long look at. My little conclusions about this and that sometimes almost sound wise to me, even, but I’m not really taken in, because I really and truly haven’t the character, the strength of character, to be wise.

I’d like to clear the way for us to be friends without any hitchy illusions. I think we almost certainly are friends. Landsmen, if you know that old intelligent Central European word.

I’m not surprised that you see already that the written word from strangers holds frightening power. . . . More formidable still, strangers use that power with such maddening insensitivity, lack of responsibility. . . . Half the time, one isn’t even written to—one’s written at. In my heaviest publishing years, the whole damn setup very nearly undid me. I must say I handled the whole thing, all those years, with something horribly close to masterly incompetence. I did just about everything wrong, responded to everything in the most uncool way imaginable. A few letters, over the years—a very few—were on the wonderful side. . . . The odd, rare letter from a sort of kinsman or kinswoman or kinschild. But those were very rare, and I can tell you without fake modesty (because it has nothing to do with modesty) that maybe no fiction writer living has had more bagfuls of public mail than I have.

Friends, relatives—they’re hell on the practising writer, too. My relatives, at least—the ones I begrudgingly and gracelessly and forcibly acknowledge as relatives—I grew to loathe during my years of most conspicuous success. Every relative of mine took unto herself or himself an emotional piece of action. Or worse. . . . You’ve seen a little of that in the last couple of weeks, haven’t you. The new life in the dining hall at Yale. Envy, resentment, fawning.

I think I’m as sure as I am of anything that you are a natural writer, if there is such a thing. . . . So, please, let neither yourself nor any maddening friends or relatives or lovers or critics give you any great or lasting doubts about that. . . . Do your work, do the kind of writing you like to do, and try very hard to be cool about the rest, to allow nobody in newsstandland to push your private buttons. Let nobody out there make you either grieve or worry inordinately—or, just as important, maybe more, let nobody’s opinion or two-cents about your output make you inordinately happy.

I’m sort of a fifty-three-year-old pantywaist and indoors country type.

I love to shoot pool, or used to.

If you’d like to go on Mr.-Salingering me, please do—whatever suits you—but nearly everybody calls me Jerry except myself.

It’s hard to be real, but landsmen stand as good a chance of simply talking together by mail as anybody else.

One of my time-eating interests, passions, is Medicine, anything that concerns healing, repairing, or just generally offsetting disintegration. . . . Both kids are tremendously experienced in recounting symptoms to me—a detailed, really careful recital of symptoms. It’s terribly touching, or at least is when I’m detached enough to think of it that way. In the end, it may be the one thing of any use that I may be able to give them.

You may wonder what’s a Fiction Writer doing getting himself all wound up for years and years with medical philosophy, therapy. I’ve done more or less the same thing with some aspects of religious philosophy, mysticism, and a few other things. Sometimes I get sidetracked from my own fictions for long months at a time, even a year or two a time, and it’s sort of a worry to me, but not always. Somebody could glibly say that all interruption of work routines is probably “karmic,” and God knows I’ve used and abused and even wallowed in that brilliant and really perilous word in my life, but the word hasn’t been coming to my mind lately, and I’m glad and relieved about it—I seem to get along best when I let my mind steer clear of all attractive Far-Eastern glossary words, marvelous and sui-generis as those words can be.

I loved all your letter, and the way your mind goes, works, and one of the reasons I couldn’t get a mailable letter out to you all weekend was that I caught myself writing to you as though we were of an age, alumni of the same years, wars, marriages, books, etc., and what you really are is an eighteen-year-old girl, though not like any other.

I think there is no limit to what you can do in your lifetime if you want to, Joyce.

This last thing, the Measure for Measure production, must have been a big strain. That whole production couldn’t sound more 1972, more With It. Almost every public step taken, in the arts or anywhere, seems to be in a nether direction, downward, maggot-ward. . . . I don’t know anything for sure about sex—I would swear no writer does or he wouldn’t have bothered all that much to be a writer in the first place—but I think the Masters and Johnson report was one of the worst things that could have happened to girls and boys, males and females, in our time. A good friend and counsellor of mine is a Reichian psychiatrist . . . and I asked him if he didn’t think the whole Masters and Johnson study was fallacious because it was made in our time and our culture, at a time when all true and real orgasmic normalcy is withheld or partially withheld, and he jumped up, in real excitement, and said yes.

I watch a terrible amount of television. . . . I’m a natural watcher. I can watch the worst of anything on television if the set’s on. . . . I do know the show Let’s Make a Deal—all those afternoon souls who have been directed to squeal incontinently when they win the stereo-broiler-exercycle combinations, the same way those couples on The Newlyweds have been instructed to kiss or bump heads when their answers tally. . . . I’ve seen some of the early Andy Griffith–Mayberry half-hours, with Opie, Barney (who was once marvelously and incessantly called Bernie by some out-of-town trollops).

Oh, actors! I was one myself once. . . . I don’t really like theater as theater. I don’t like Curtains, I don’t like entrances, exits, movement on stage, larger-than-life readings of lines. I don’t like “beautiful” sets, I don’t like bare sets. Directors, producers, programs—there’s magic in it all, no doubt, but it acts on my system like small amounts of poison.

I love, really love, writing for the printed page. . . . What I love, what intrigues me, is the little theater inside the private reader’s head. Maybe, in fact surely, not all private readers’ heads. . . . I don’t read much fiction anymore.

I myself have never had Sheer Guts. I’ve chickened out of many things, but many. . . . I don’t think not having some courage necessarily disqualifies anyone from certain kinds of bravery. I myself have been peculiarly brave, unnoticeably brave, a few times in my life, and I have never felt like a “coward” for not having much natural or ready courage. . . .

The very few people I have known whom I’ve considered to be out-and-out cowards were in most popular respects fearless insensitives. I once shared a foxhole for part of an afternoon with a nearly fearless lout, and it was a revelation.

You’re surely not lacking anything important, Joyce. That piece you did for the Times Magazine Section was written by a girl who has everything.

I really don’t understand these exchanges between us, this kind of talking we do. I can tell you I’m not accustomed to any of it. . . . If it’s sometimes hard to write back and forth, maybe it could be because we are, or have the makings of, close friends, but on short acquaintance. Hurray for us for managing anyway!

I haven’t shaved in a week. . . . I look like a black-hat type in a Monogram Western.

Just in case of anything at all, my phone number here is 603-675-5244.

Next Saturday . . . I’ll be driving down to Boston to collect Peggy and her stuff—end of term. I thought of asking you what you might think of [a] handshake between us, on the way, but I think while you have work going, work-about-to-be-finished, that’s probably not such a hot idea. Still it would be so very nice, from my point of view, to meet you before too very long.

If you’d left four-foot margins in the last letter, I think I’d be replying, responding, to every word in it. . . . I want to answer or answer back to little tiny worries and things in your letter. . . . I think I tend to form lasting attachments to anything personal you say in my direction. Miss Maynard.

You really have to let me defend myself against the accusation that I overestimate you. . . . You also said, in this last letter, that I make you feel much more special than you really are. . . . Something in or around it all, your writing, lets me have peace, satisfaction, arouses affection in me, makes me feel all right. . . . Your mind happens to put me in a nondescript state of armistice. Your words suit me. When you call yourself Good-sense-ish, the word calms me, works on me just right—I’m both happy and not surprised that you consciously or unconsciously discarded Sensible for this much better, righter word. . . . For me, you write and think the way you look.

About the world being full of people with whom I’d feel equally close if they, not you, came to visit. . . . It’s utterly unlike me . . . to walk into a news store in Windsor on a Sunday morning with a Guest. . . . It seemed natural to appear there with you.

I, too, have never had a friendship like this. At no time. It makes me cheerful, even outwardly, on the whole. For instance, I smile (I think) at your tendency to look ahead and worry that we’ll make each other miserable. It’s exactly the kind of grey reflection that usually goes through my head. . . . I don’t picture us making each other miserable, and what I don’t picture I don’t tend to believe. Do you picture us making each other miserable? (I said do you, not can you.)

I can see that I might sometimes hover, watch you anxiously. Partly my age, partly not my age, at all—there is a yin, a pretty feminine side to my nature that crops out; I’m as maternal with kids, for instance, my own or not necessarily just my own, as I am paternal. . . . Medicines, food, hatha yoga, publishing—all a form of hovering, of unsolicited watchmanship. . . . On the other hand, I’m usually so self-centered or so self-absorbed, like any inveterate writer and narcissist, that I scarcely notice what people are doing or wearing or eating.

Every time we publish something, produce something, air something, we’re about to be re-judged, weighed, tagged, squeezed, bagged all over again. I think we have it coming to us, for a lot of reasons. . . . But something else you said does make me sort of lean my mouth and chin into the palm of my hand pretty gravely, maybe too solemnly. The word “embarrassment” as you used it—underlined—embarrassment. I know that kind of embarrassment. . . . We don’t have to feel that kind of embarrassment, and I say we shouldn’t, that it’s bad for us, a little too damaging. . . . Please determine and succeed in being wise about this one little matter. Please try to see the readership, the publishing-time attention of close and dear relatives, friends, all really ardent well-wishers with as much pure detachment as you can. Maybe it’s sort of cruel to deliberately cast an occasional highly-detached eye—a cold eye, to spit it out—on the best and closest we’ve got, but it can be done pretty privately, with no pain for them, only a little guilt for us. . . .

I don’t understand what I’m talking about, yet I go on talking.

I’ve missed you all day.

It makes me uneasy to realize that I may sooner or later be at least one kind of annoyance to you.

So many thoughts of you.

Shall we think about our plays and our sumptuous suite at the Waldorf or the Claridge? The answer to that could well be an emphatic yes rising out of me, but right now, today, at this pasty midnight hour, I don’t feel up to thinking about matters so concrete and explicit.

I miss you pretty sorely.

Never thought of it, but we should have had a go at reading “A. and Cleopatra” out loud, just for fun.

A whole week we had, nearly. A great portion of fairness in my life. We didn’t do, so much; we were.

I miss you very uncomfortably, and I can’t say that I have anything particularly contributive to add to your grave ruminations about common sense and your age (or mine) and moving in and (spear through the stomach) moving out. If Movings In inevitably lead to Movings Out, I emphatically tend to be in favor of separate quarters, be they ever so bleak or humble or dessicating. Maybe that’s going too far, but it’s very plain to me that I’m not responding to any of your goings, leavetakings, Standby Flights with anything that could pass for genuine Cool. . . . What the hell is Cool, anyway? Freedom from, or severance from, attachment. I’ve been examining the matter, off and on, for a lot of years, and I remain the same lightweight outsider-onlooker that I was at seventeen.

Your beautiful letter. Oh, yes—beautiful.

I was very conscious . . . of Peggy’s not knowing or understanding or loving anything about Jews and Jewishness—Torah Jews, shtetl Jews, displaced Jews—and probably the only ones she will ever know are a few private-school boys cut off from all that, and glad of it, in most cases. Beards without Jews. One of the Hasidic Rebbes casually, sadly, alluded to a man in his congregation who had fallen seriously from grace as “a beard without a Jew.”

I miss you, love you, love your two letters, and I have no idea, by the way, how Holden got so much into one night. I could ask Joyce Brothers. Boy, is she smart.

I feel your not-here-ness countless times a day, and I don’t know what’s wise to do about it, or even if there is anything wise to be done about it, and so, because I know nothing, I write and mail jaunty-sounding letters.

I’ve been around jazz enthusiasts a lot of my life, having known a few jazz people, and certainly I’ve listened to quite a lot of it, and I don’t think I listen to it like an out-and-out dummy—at least, my foot keeps time and I may occasionally tap out the beat with my finger on my water glass. I like a lot of it, in short, and I know about the fun they have, the improvisers. Why shouldn’t they? They mostly do what they do in groups of two or more, and they feed each other pre-stylised musical patterns, musical idioms, almost always identifiably based on past sets, other sittings, performances, pieces. Even the jazz musician working alone, the soloist, rarely does anything distinctly new, anything never-done, anything mouth-shuttingly firsthand. Even when the jazz improviser is in top form, hottest, what he’s mostly doing is relying (with almost perfect confidence) on a composite or combination of . . . effects that are already developed within himself and that he knows will almost absolutely surely rearrange themselves in “new” kaleidoscopic (sp.?) patterns if he applies himself to his instrument assiduously, affectionately, in the mood with the others or just with the occasion, and provided he isn’t too drunk or stoned. I’ve seen it happen again and again, and it never fails to under-impress me, even when I’m listening with real pleasure.

It just seems to me a perfect unwonder that writing’s almost never terrific fun. If it’s not the hardest of the arts—I think it is—it’s surely the most unnatural, and therefore the most wearying. So unreliable, so uncertain. Our instrument is a blank sheet of paper—no strings, no frets, no keys, no reed, mouthpiece, nothing to do with the body whatever—God, the unnaturalness of it. Always waiting for birth, every time we sit down to work.

I love your life, and I love writing that’s real writing.

When your days at the Times are over this week—Thursday? Friday?—do you think you might be able or willing to take a plane up here, stay here . . . till Sunday or Monday or Tuesday, and then fly or drive to New York with me? . . . Does that sound any good or possible?

I have only movies, no Films, including, I’m afraid, “Lost Horizon.” I’m really a terrible lightweight.

When you’re in New Haven next year, I thought I might rent a place in Westport or Stamford, kind of halfway between New Haven and New York. Does that seem to you a fairly thoughtful idea? I don’t think I could take stewing in my own juices up here all winter, almost totally out of sight of you. And though there’s no good reason why I couldn’t see you in New Haven, occasionally spend the night, say, on your chiffonier, it would be a bad idea, I think, if I were to move into New Haven on any more staying-on basis—you’d have no easy or “normal” campus life, college life, with me around, and I comport myself lousily around campuses anyway, but really lousily. . . . What I learned, if anything, while you were in Miami is that I am not able to be bleedingly alone and cut off while you’re away. I take to it badly, really badly. . . .

My mind is complicated, and I have to take measures, always, to live as I’d advise myself to live if I were my own mentor.

What a relief, pleasure it is to love your mind, really love it.

The Prom piece is so good. Even when you’re busy just reporting, it always comes out real writing, and all your own. I think I would know your writing anywhere.

You play the bugle well, as the man said, and I read you with an old and passionate love for writing that I seldom feel any more or, for that matter, miss. . . .

When I pulled up at the Post Office yesterday afternoon, Peggy and Matthew pulled up behind me. A lot of grinning, happy looks exchanged in a flash. God, it’s good to love a few people in the world.

I miss you and gave myself a rotten short haircut. On your head be it.

I think very, and only, lovingly of you. I love lastingness, permanence, and I wish us nothing less. Permanence, not petrifaction. There must be a difference.

About five hours later. Guests have come and gone. It was strenuous talking, question-and-answer talking, and one of the reasons why I moved up here in the first place. I’m full of my own wine and beer at this point. How I dislike drinking on social occasions—that is, pure social occasions, not connected with contentment or some sort of celebration. . . . I wish I felt closer to them all. They act as though they feel close to me, and that makes me feel guilty and irritated at once. It was pretty, up on the hill, though, and I really like them all; I just like smaller doses. . . . Even when I was being drawn, as though forcibly, into the worst and deadliest kind of literary talk, I recovered some balance simply by thinking of you and my love for you.

I feel restive and very edgy. I always was a poor yogi. It sometimes seemed to me all my real yoga was in knowing that.

Love,

Jerry