I spend a long time composing my response to J. D. Salinger’s letter on my yellow legal pad. When I’m done I type it carefully. Like my mother, I place a piece of carbon paper and second sheet underneath: “Dear Mister Salinger, I will remember your advice every day of my life. I read your letter over and over, and carried it in my pocket all day. I no longer need to read it. I know it by heart. Not just the words, but the sentiments expressed.

Joyce Maynard

JOYCE MAYNARD: My first experience of Holden Caulfield was not in The Catcher in the Rye. It was in the letters of J. D. Salinger. It was that voice; if the letter writer had been someone I’d never heard of, I would still have responded to that voice. It’s exactly the response that generations of readers of Catcher in the Rye have experienced—the sense, finally, that there was somebody who knew me, recognized me, and understood me as I felt nobody ever had. I fell in love with the voice in his letters.

Within three days, there was a second letter and then a third and a fourth. I just told him about my life, told him college stories. It may have been part of his attraction to me because he was living a very isolated life, high on a hill in New Hampshire, cut off from many things. I brought news of the world from a young person out there in it. I told him about all the girls jumping on and off scales, weighing themselves; I was one myself. I told him that I liked to ride my bicycle into the countryside outside New Haven. I told him that I didn’t have many friends there, that I made dollhouse furniture, that I listened to music, that I drew. I told him about the three girls who were my roommates; I was the only one who didn’t have a boyfriend, so I left for a “psychological single.”

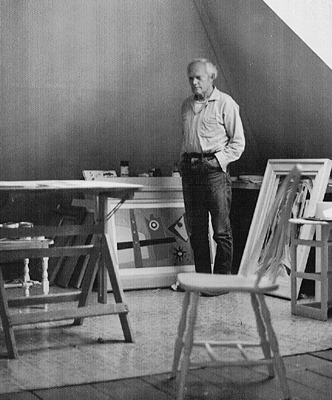

Both of my parents were brilliant, gifted artists. My father for thirty-some years was an assistant professor of English at the University of New Hampshire, never promoted. His true passion was art. He painted in total obscurity for almost all of his life. He never made any money. My mother had a Ph.D. from Harvard and couldn’t get a job at the University of New Hampshire because she was a woman married to a man who had one. I felt a huge obligation to deliver at my parents’ feet the success and acknowledgment that had eluded them.

I would tell my father stories; I loved to entertain him, which had been my role in my family. He described Scheherazade to me, how she keeps on telling stories so she won’t be killed, and I always felt a little bit like Scheherazade, not because my life was in danger, but my place in the world was ensured by my storytelling. I didn’t know who I would be if I didn’t entertain and charm and delight.

And now I was entertaining and charming and delighting Salinger. I knew that I had won the approval of this great man, and I knew that it would make my parents very happy. For my mother, it was as if J. D. Salinger had recognized her, since I was her product. My mother was a little unclear of boundaries—where she left off and I began.

Joyce’s father, Max Maynard, a painter, in his studio.

A young Joyce Maynard with her parents.

I was not a relaxed and comfortable college student. I was anxious and tormented in a lot of ways. If I were a person who was having a happy life at college, I probably would have responded very differently to this voice than I did, but I was living alone in a top-floor dormitory room, and I poured out my heart to him. More and more, the energies that other people might have been putting into friendships, classes, and Yale went into those letters.

I sensed from the beginning he had an idealized vision of me. I was perfect. I didn’t want to do anything to disappoint him.

One of the very early pieces that I published ran in Newsweek, in the “My Turn” column, and was called “Searching for Sages.” I was looking for a sage and the meaning to life. I found it with Salinger. I was raised in a family with huge respect for language and art. Some people could be seduced by a Jimi Hendrix guitar riff; I could by words. Words were the religion of my family, as were intelligence, excellence, and humor—all of which I found in Salinger’s voice. Before I could physically write, I gave dictation. My mother typed up my work. We would sit around the living room, reading our manuscripts. The moments of purest joy and perfection in that relationship with Jerry lay in the weeks before I ever met him when we communicated on the page, and on the page it was perfect.

There’s only one other time in my life when I experienced the phenomenon of letters having an equivalent power of seduction, seduction by words. It was a man serving life in prison for double murder. He had only words to pull in a woman, and he did it very well. Salinger was a master at that. Getting a letter from J. D. Salinger was like getting a letter from Holden Caulfield, but written just to me—Holden Caulfield telling me how wonderful, perfect, lovable, and brilliant I was. It was a pretty strong drug. It was the only drug I took in college.

He had suggested that I call, collect.

“Is this Jerry?” I began, when he picked up the phone that first night. “This is Joyce Maynard calling.”

“What do you know? That’s terrific,” he said. He was a little out of breath. “I was just down at the garden, putting in the last of my tomato plants. Black flies are murder this year. What have I been telling you? Everybody’s after your blood.”

Once we started exchanging letters, I always knew we would meet. There was never any question that we would meet. There was never any discussion; it was just understood. On the one hand, I couldn’t wait to meet him. On the other, I was afraid that I might disappoint him and that the meeting couldn’t live up to what the correspondence had been. Of course, it turned out I was right, although our first meeting, after I got the courage to go up there, was wonderful. School got out in early June and that’s when I went to meet Jerry. I had been raised to believe that I was going to do big, important things, and this was a sign that I was going to.

My favorite English teacher from high school, from Phillips Exeter, was driving up to Hanover, so he drove me. He was an early encourager of my work, a real friend. Many people, I know, look back on it all now and wonder, “My God, what was going on there?”

This part makes me sad—because I really loved my mother, and I know her to have been a wonderful woman, but she offered me up to Jerry Salinger in a way. She sewed me a dress for our meeting. The fabric was meant to be curtain fabric for a child’s room. It was the A-B-C’s. I was very skinny; it didn’t take a whole lot of fabric.

Joyce Maynard’s mother, sewing.

It was a basically an A-line dress, very short, with two very large buttons at the shoulder. You just unbuttoned them and the whole dress would fall off. There were two very large pockets onto which she had appliquéd letters: an A on one pocket, and a Z on the other. Very bright primary colors. A very short dress. It looked a lot like the dress I wore to first grade. And that’s the dress that I was wearing the day I met him.

Joyce Maynard, 1973.

He raised his hand and was waving as if he were somebody coming in off a boat. He actually jumped over the banister; there was something very boyish about him and very graceful. He was like a soft-shoe artist, and we just started right in. Finally I was here. I threw my arms around him. I hugged him. He hugged me back. The very first thing Salinger said was, “You’re wearing the watch.” It was a very large watch, a man’s watch. Clearly he’d really studied my photograph in the New York Times.

“We are landsmen, all right,” he said.

My heart lifted. I had spent less than an hour in the company of Jerry Salinger, but I was feeling something I’d never experienced before.

“I’ve waited a long time for you,” he said. “If I didn’t know better, I’d say you belong here.”

I jumped in the front seat of his little BMW. I’d never known anybody who had a standard-shift BMW. I felt like I was in a French film. He drove fast and skillfully, but now and then he looked over at me sitting on the passenger side and smiled. We drove very fast along New Hampshire and Vermont roads, under covered bridges, winding up the hill to his house. It was hard to know where to begin. On the other hand, there seemed no need to say anything. For the first time in as long as I can remember, I felt no need for speech.

There was nothing particularly fancy about the house. Books stacked everywhere. Movies stacked everywhere. In Peggy’s room there were just stacks and stacks of movie reels. The living room had soft velvet couches and piles and piles of New Yorker magazines. Deck in the front looking out at Mt. Ascutney. There were no personal items, photograph albums, photographs, letters. And then there was another wing of the house, which was his bedroom and his writing room, but I didn’t see that until later.

Nothing seemed strange to me; it was as if this were the most natural thing in the world. It confirmed what I had been raised to believe: I was going to do important things, and I was going to spend time with this wonderful man. I was going to learn many things.

He made a bowl of popcorn, threaded a film through the projector, turned out the lights, and it was movie time. That first night, we watched The 39 Steps; that was one of his absolute favorites. Afterward we talked and I went to bed.

I slept in Peggy’s bedroom. She was out, playing basketball, and then off with her boyfriend; she was going to be gone very late. And Matthew was also spending the night. So I did meet Matthew, who was a very lovable, happy, funny, charming twelve-year-old boy.

Peggy came in in the middle of the night, very late. I recognized on that first visit he was very critical of her in ways that he wasn’t of his son, but she was strong and tough. Not too many people challenged J. D. Salinger, and she did. I don’t think Margaret was more rebellious than any other sixteen-year-old. She was just doing her job, which amazed me, because I hadn’t done my job.

I don’t remember feeling embarrassed that I was here, visiting their father. Everything was unusual. J. D. Salinger was unusual. What was normal life? This was J. D. Salinger’s life.

There was no question that I was going to see him again. Ten days after I’d begun my summer job as an editorial intern with the New York Times, Jerry drove five hours to pick me up. I was house-sitting a Manhattan brownstone for the summer; when he pulled up in front of the brownstone on West 73rd Street, I came running into his arms. He stroked my hair. “God, I’ve been waiting forever for this,” he said.

We bought a bag of bagels and lox on the Upper West Side. Then he turned right around and we drove, very fast, the full five hours straight back to New Hampshire.

Over the course of that summer, I probably visited Jerry two or three times, for the weekend. I still had my job in New York, and he’d come down to see me; he stayed at the house on West 73rd once. But by July I missed him too much. I wanted to be with him all the time. I’ll put it a little differently: I felt I needed to be with him all the time. I began to feel what the relationship required was for me to be with him all the time. I don’t suppose that I was really listening to my own feelings as much as what I felt were the requirements for me—and that had been my story all my life. So I turned in my notice at the New York Times. In fact it was no notice at all. I said, “I’m leaving,” then I called up the family who had given me responsibility for their house on West 73rd and said, “You’re going to need to find another house sitter.” And within a couple of days, I was gone. I published, I think, two editorials; two editorials written by me were published in the New York Times—without my name attached, of course—that summer. And then I moved into Jerry’s house, but still with the belief that I was going back to Yale in the fall.

In the article that inspired him to write to me, I had mentioned that I was a virgin. I talked of the sexually open climate at Yale my freshman year and how uncomfortable it was to be a virgin there. One of the many offers that had come my way, as a result of that article, was an invitation from Mademoiselle to write an article, which was published that summer, called “The Embarrassment of Virginity,” with a photograph of me sitting in my dormitory room being a virgin.

The next time I came up from New York for the weekend, it was different, and I guess I knew that it was going to be, although I didn’t have a clue how it would happen because I had kissed two boys in my life and no men. Nothing was discussed. He took me into his room, and I didn’t ask any questions when he took my clothes off. I had no frame of reference, didn’t know how else it could be, but it wasn’t a particularly tender romantic scene. We got into the bed and he kissed me and then he began to—I’m very careful when I use the phrase “make love,” because it gets thrown around a lot, and this actually was not really making love—an attempt was made to have intercourse. There was no discussion of birth control, although I was eighteen years old, but it was not possible, anyway. I couldn’t do it. It didn’t happen. The muscles of my vagina simply clamped shut and would not release. After a few minutes we stopped.

It was excruciatingly painful and I almost instantly developed a headache the likes of which I had never experienced. My whole head was exploding. I felt very embarrassed; that was my chief emotion. We didn’t discuss it, and over the course of the weekend it was attempted on numerous other occasions and the same thing happened. At the time, I was mortified and felt like an absolute failure and a freak. He said gently, “Tomorrow I’ll look up your symptoms in the Materia Medica,” an ancient Chinese homeopathic text. Jerry spent a great deal of time researching homeopathic remedies for me to assist my condition.

Nothing that took place with Jerry Salinger had remotely the aspect of a boyfriend-girlfriend, dating relationship. I was his sidekick, his partner, his protégée, his student. I was his student of writing, I was his student of life, and I was (and I was certainly a failure here) his Zen acolyte. I studied, through him, health principles and homeopathy, but I was not his girlfriend.

He assigned to me some of the responsibilities of a sexual partner. I’d follow him into the bedroom. We’d stand together at the sink, brushing our teeth. I’d take off my contact lenses, go into the bedroom, take off my jeans and underwear, and put on my long flannel nightgown. Jerry would come into the room. He’d undress, put on his nightshirt, and climb onto his side of the bed. I’d get onto mine. His hand would reach for my shoulders. He’d stroke my hair, then take hold of my head with surprising firmness, and guide me under the covers. Under the covers, with their smell of laundry detergent, I’d close my eyes. Tears would be streaming down my cheeks. Still, I wouldn’t stop. So long as I kept doing this, I knew he would love me.

He certainly said he loved me, always, almost from the beginning. I certainly told him every day that I was with him that I loved him, but it was its own category.

Joyce Maynard, meditating.

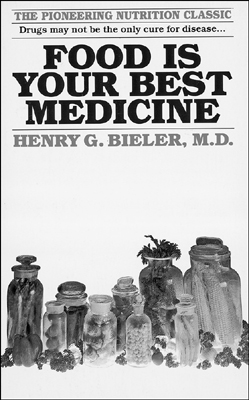

We had a very set routine—the things that we did and the foods that we ate and the times that we did these things. We were very early risers. The first thing we did was have a bowl of Birds Eye frozen Tiny Tender Peas, not cooked, but with warm water poured over them so they’d defrost a little bit, so they were just cool. There was a book whose principles he subscribed to called Food Is Your Best Medicine. He was a believer in raw food; he was actually way ahead of his time in many ways. Then we’d meditate, or at least he would meditate and I would try to meditate. Jerry tried to make me into a student of Zen to leave worldly things behind, but my mind kept on wandering to things of the world, which was a big problem.

Cover of Food Is Your Best Medicine.

He would meditate for a long time and I would get restless and then we would get to work writing. He would put on a one-piece canvas jumpsuit with snaps up the front and he’d put it on like a uniform. It was kind of like he was a soldier or something, only he was going off to wage his war at the typewriter. He sat on a high chair at his high desk in his writing room and worked on his typewriter, a very old typewriter that clicked. I heard typing every day. I saw two thick manuscripts. I’ve written nine books now. I know what the size of a book manuscript looks like, and these were thick. I never read anything. He did show me one thing, although it wasn’t like I got to sit down and read it, and that was an archive of the Glass family; it was almost a genealogy. He was as protective of those characters as if they were his children. I never laid eyes on a page that he was writing. Never. And there was one other space that was off the bedroom and I believe that was his safe. We met at lunch to discuss life, and I would show him my pages. I had signed up to write an expansion of the New York Times piece into a book.

Salinger in his jumpsuit.

I knew, without asking, the nature of Jerry’s view of publishers. “Give me two hours in the dentist chair before I’ll spend another minute in a publisher’s office,” he said. “All those insufferable literary types, thoroughly pleased with themselves, who haven’t read a line of Tolstoy since college. All feverishly courting bestsellerdom. Not that the absence of any true original gift or insight keeps them from demanding all manner of pointless alterations to a writer’s work, for the sole purpose of proving their own irreplaceable talents. They’ve got to offer up all these bright ideas. Unable to produce a single original line themselves, they’re bound and determined to put their stamp squarely on your work. It happened to me plenty of times. Polite suggestions that I change this or that, put in more romance, take out more of that annoying ambiguity . . . slap some terribly clever illustration on the cover. . . . The minute you publish a book, you’d better understand, it’s out of your hands. In come the reviewers, aiming to make a name for themselves by destroying your own. And they will. Make no mistake about it. It’s a goddamn embarrassment, publishing. The poor boob who lets himself in for it might as well walk down Madison Avenue with his pants down.”

Every afternoon we drove down the hill and bought the New York Times. And many of those afternoons, as we came down the hill and passed the mailbox, there would be some seeker standing at the foot of the driveway. In all of the time that I was there, nobody ever knocked at the door. It was an unwritten rule of the religion perhaps. Then we’d come back and watch TV. He loved Mary Tyler Moore, Andy Griffith—Ron Howard with his fishing pole over his shoulder. We used to watch the Lawrence Welk Show. It was partly sort of a kitsch thing that we did, but it was also about watching America. He officially cut himself off from a great deal of the world but maintained a huge interest in observing it. We’d watch the show and we would dance. I was, you know, a girl of the ’60s and ’70s. I didn’t know couples dancing. And he was a very good dancer, so we would dance in the living room to Lawrence Welk while all of my contemporaries were off in New Haven, doing drugs and listening to Led Zeppelin. Sometimes we’d go to the movies—not very much—because mostly we watched old movies in Jerry’s living room.

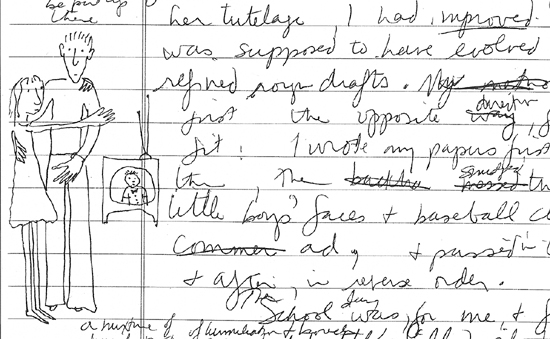

Joyce Maynard’s drawing of herself dancing with Salinger to Lawrence Welk.

He loved Maltese Falcon, Casablanca, The Lady Vanishes, W. C. Fields. He loved Lost Horizon. He had a deep interest in Marlon Brando. Jerry’s first love had been acting, and he was a wonderful performer. Very funny. And he had a beautiful voice. He said that the only person who could ever play Holden Caulfield was himself. But even he acknowledged he was too old for that, although, in some ways, he was playing Holden Caulfield forever. He had been pursued, of course, for years for the movie rights to Catcher in the Rye, but the one who was determined to play Holden Caulfield was Jerry Lewis. He said Jerry Lewis always called him, but he said he would never let Hollywood make any movie of his again.

It’s a long list of institutions that Jerry had contempt for: Western medicine, mainstream Hollywood (although I think he was secretly semi-dazzled by it), psychiatry, Ivy League education, families (there was another institution). I remember listening to very old recordings of the Andrews Sisters and Glenn Miller and an obscure German singer whose name I don’t remember but who was a singer from World War II. And then we’d go to bed.

I moved into Jerry’s house that summer, still believing that I was going back to Yale in the fall. I had rented an apartment, using part of the book advance from my book that I was due to deliver within a few months and that I’d been working on. I had gone out and bought furniture. I bought plants. I got dishes. I unpacked my bags. I registered for classes. Jerry made a joke about how I’d probably meet some Joe College, and then I’d forget all about him.

I never attended a single class of my sophomore year. I withdrew from Yale two days later, forfeiting that fall’s tuition, plus my scholarship. I remember the movie that Jerry brought to screen when he came to get me. He brought the projector and everything to my apartment on George Street in New Haven, he set up the projector, and we watched A Night to Remember, the real Titanic movie. I piled my clothes in the back of his car. He’d brought the BMW, not the Blazer, so I left most of my possessions in the apartment.

For most of that year, I lived with him, believing that despite the thirty-five years separating us, we would be together always. I didn’t think I’d ever leave again after that.

When he was loving, he was extraordinarily tender and certainly funny. I found myself in a relationship with him that reminded me, with the exception of the drinking, of my relationship with my father. I was entertaining him, trying to make him happy, and not very successfully. The moment I moved in, I could do very little right. He said to me the day I moved in, “You’re behaving like a teenager,” which I was.

I didn’t swim that summer, or ride my bike, or drive anywhere without Jerry, except one time, when I got to take the Blazer (never the BMW) to a Singer sewing machine store. I spent $400 on a Singer Golden Touch and Sew machine. “This baby would have come in handy in a foxhole,” he said as he lifted it out of the back of the car and carried the machine up the stairs for me. “Put one of these on your head and you wouldn’t have to worry about shrapnel fire.” I should have been buying an electric typewriter. I had to write a book in the next three months.

My birthday in November passed as just an ordinary day. Three days later, Nixon was reelected. Neither of us voted.

Only one time did I meet friends of his, and that was this memorable and disastrous lunch; I don’t have a clue what he was thinking. We drove into New York in the BMW, very fast, as always—a trip that took probably about five, six hours. We went to the Algonquin, and there was this tiny little man who I realize now was probably only in his late fifties, but he seemed very old to me at the time: William Shawn. I had heard about him for as long as I’d known Jerry. And with Shawn was Lillian Ross, whose work I knew; I’d read it and studied it and admired it. This was years before her book in which she disclosed this information, but I knew from Jerry that Lillian Ross and William Shawn had been lovers for years. It was a known thing in certain circles, but never referred to, even with Jerry.

Lillian Ross and William Shawn.

Lillian Ross, a writer at the New Yorker.

We took our places around this table at the Algonquin. I remember being really excited that I was meeting the editor of the New Yorker and this writer whose work I’d read and thought was so wonderful. She asked me what sorts of things I’d written, and, well, my main publication had been in Seventeen magazine. So I began talking to her about writing for Seventeen, judging the Miss Teenage America pageant, and interviewing Julie Nixon Eisenhower. I realize now that she was rather baiting me, while I thought I was being amusing and entertaining. Ross shot Shawn a look. The same eye that I had so admired on the page looking critically and highly perceptively at other people’s foibles was suddenly turned to me. I can imagine the cruel “Talk of the Town” piece she could’ve written about me.

When lunch was over, Jerry put me into a taxi, and we went directly to Bonwit Teller, rode the elevator up to whatever floor it was that sold the most elegant, most sophisticated coats of a sort worn most particularly by middle-aged, professional women in New York City. He bought me a very expensive, black, cashmere coat of the sort that Lillian Ross might’ve worn, which was not at all like what the rest of my wardrobe resembled. I’m sure I was wearing a miniskirt that day. I’m sure Jerry was ashamed of me; that’s why he wanted to put me in an expensive coat.

I was writing Looking Back and it was going to be published in a few months. Every day I worked on the book, I showed him my manuscript pages; I read every page out loud to Jerry over the course of the months I spent writing it, much in the way I used to read my work out loud to my father and mother. Certain sections Jerry typed for me. He made handwritten comments in the margins on yellow legal pads. After he completed reading over my manuscript one morning, he said to me, “Plants and animals are the telling omissions in your recollections. Too many passing fads here. Too little that is lasting.”

I drove down to New York with Jerry to have my photograph taken for the book. I posed in Central Park with him standing just off to the side, watching. I met editors to discuss promotion of the book. We never discussed how on earth Jerry was going to maintain his privacy—I won’t even call it privacy; the secrecy of our relationship—with a major publisher’s publicity campaign well under way to promote the book. I don’t really believe that Jerry felt we had a future anymore. He just didn’t tell me. I can even feel some sympathy for him: I suspect he didn’t know how on earth he was to get out of this mess.

One day I heard the telephone ring and wasn’t supposed to answer it, ever, so I listened to Jerry answer the phone and there was a very brief conversation, then a click. He emerged from his office with a kind of anger on his face I had never seen anywhere. He said, “Time magazine has got my number; you have ruined my life.” The call had been a reporter from Time and it became, a week later, an item in Time’s gossipy “Newsmakers” column: “Former Yale coed, Joyce Maynard, is living with J. D. Salinger.”

Worried about Jerry, I decided not to promote the book. I would just let it be put out there without my presence. My editor at Doubleday, Elsa van Bergen, wrote me a letter expressing her concern and dismay about my decision not to participate in the publicity. What Elsa said in her letter made sense to me, and for a moment, reading it, I felt a small surge of hopefulness. Maybe I didn’t have to close myself off from the world altogether. Perhaps my continued interest in things like bookstore appearances and interviews was not unforgivable. I brought the letter to Jerry, who read it only partway through, then folded it neatly and handed it back to me with a sigh. “Perhaps you’re like the rest of them after all,” he said.

I felt like a fraud. In the name of protecting Salinger, I had betrayed myself. There was no way to write the story of myself without explaining the story of Salinger.

During all this period, although it became increasingly dark, I never thought of leaving. I never imagined that the relationship would end. I continued to envision and actively discuss a future, although the dream of a romantic sexual relationship was over before it began. The dream of parenthood replaced it; what I wanted most was a family. I pictured having a child with Jerry, and it was always very specific: I pictured a little girl. How this child was to be conceived I can’t imagine because nothing was happening that would have made that possible, although we actually had a name for this child.

It was a name that Jerry came up with in a dream: “Bint.” The little girl was always referred to as “Bint.”

Only much later, after I published At Home in the World, did I get a letter from a British scholar who said, “Do you know what the word ‘Bint’ actually means? It’s a word that means ‘whore,’ worse than ‘wench’; it’s a very ugly word for a woman.” I didn’t know that at the time. We were going to have Bint because one of the things you do if the present isn’t so great is think about the future.

Apart from our trips to New York City, we’d never actually been anywhere together. Jerry announced we were going to take a trip to Florida in March, during Matthew and Peggy’s school vacation. Truthfully, I would have loved to have taken a trip that was just the two of us, but I was not about to argue about anything in that relationship. I was happy to be going to Florida because it was very cold, dark, and snowy that winter, like most winters in New Hampshire, but it was particularly cold and dark in my memory of it. Jerry was a serious follower and student of homeopathic medicine. He located a homeopathic practitioner in Daytona Beach whom he wanted to consult about my inability to have sex. This was not, of course, described to Matthew and Peggy, who thought we were just going to Florida for a vacation.

On day two [of the Florida vacation], Jerry left Matthew and Peggy at the hotel pool and we went off to see the doctor. He didn’t identify himself as J. D. Salinger, of course; he called himself John Boletus (“boletus” is a type of mushroom), and I was his friend whom he was assisting with her problem. Jerry didn’t identify himself as my sexual partner. I was silent throughout this entire meeting, but Jerry explained the nature of the problem in very clinical terms and then stepped out of the room so she could examine me. I’d never been examined that way by a doctor before. She invited him back into the room and discussed, mostly with Mr. Boletus, various homeopathic remedies that might be used on me. We paid and left.

Matthew wanted to, I think, fly a kite, or he wanted to play in the water, or he wanted to do something that a twelve-year-old boy would, understandably, want to do with his dad on a vacation. After Jerry played with Matthew in the water for a while, he came back to the towel where I was sitting. He looked very tired—not just tired; he looked weary—and he said to me, “I can’t do this anymore. I’m finished with all of this. I’ll never have any more children.” I said, “Then I can’t stay.” And he said, “You’d better leave now then.”

I think I knew I had to leave right then: I picked up my towel off the sand and I started walking back toward the hotel. Staggering is probably more like it. And I know I believed that he would come after me. But he didn’t. He stayed on the beach with the children. And I went back into the hotel room. And I didn’t have any money, I didn’t have a charge card, I really didn’t have anything, I was just there in Daytona Beach with my towel. I called my mother, and I said I have to come home now. And then she said, well, I’ll try to find you a flight. But there was no flight until the next day. So I had to spend one more night there.

We carried on in a kind of a way and we went out to dinner. Then we did what we usually did: we saw a movie. We went back to the room and I should say that we had two hotel rooms, one of which was Matthew and Jerry; the other was Peggy and me. We shared a room. Peggy and I were never friends. Peggy didn’t really talk to me and I was afraid of Peggy, but Peggy and I were in a room together. So I knew that I still couldn’t make a sound. I lay in the bed just kind of trembling, and I couldn’t stand it anymore, I had to see Jerry, so when it was very late and I thought that Peggy was asleep and Matthew was asleep, I went in and I got Jerry.

We went into the only place where we could be alone, which was the bathroom. And I said please. I can’t leave you. Please. Let me stay. I don’t have to have any children. It was the last piece I think of me that I relinquished at that moment. And he said no, you need to go. And the next morning I packed my bathing suit and my flip-flops in my bag, and I rode the elevator down to the lobby with him. He called for a taxi and he leaned over and said to the driver, This girl needs to go to the airport now, and gave me, put two $50 bills in my hand.

And I drove away

I don’t remember how I got back to New Hampshire. I know snow covered the steps to his house when I climbed them. The heat was off; it was very cold. I packed up all my things and called my mother to come and pick me up. The last thing I did, rather melodramatically, before I left the house, was to write, in the ice on the window, BINT. I went home.

Three weeks later, my memoir Looking Back was published—a 160-page book ostensibly about my life as an eighteen-year-old, in which I never mentioned that my father was an alcoholic or that I, the anointed youth spokesperson of 1973, had dropped out of her Ivy League college and moved in with a fifty-three-year-old man who happened to be J. D. Salinger. None of it appeared in the book, although it was written in his house.

Cover of the book Joyce Maynard wrote while living with Salinger, who was five feet away when this picture was taken.

After he was gone from my life, I called him. It’s embarrassing to think how long and how pitifully I pursued him. Calling him and begging him to come and see me, talk to me, take me back. I felt as if I was in exile. The same voice that had spoken to me with such exquisite tenderness and concern was almost unrecognizably cold. And I knew his heart had left the room. I continued to send him letters. I called him for way too long—trying to get back to that place I had known, that little patch of sunlight I felt I had briefly inhabited with him. I lived a very solitary life. I was on my own at this point. When I called Jerry, it was clear that my calls were excruciating to him. He just wanted me gone. He wanted me off the phone. I don’t think he ever quite hung up on me, but in essence he didn’t have to. His response was so dismissive and withering. I couldn’t bear it. He finally said, “Go away. Stop calling me.” He said, “I have nothing to say to you.” I would say, “I don’t know what to do, I don’t know where to go.”

I bought a house in Hillsboro, New Hampshire, and I was living there and really trying to create a life Salinger would think was a good one. It was never enough just to have the good life. It had to be a life that he thought was a good one. I bought books. I made a little writing space for myself, which I kept asking him to come and visit and see. Finally, I think just to get me off his back, he agreed that he would drive by, and I was extraordinarily excited and anxious. I remember preparing for days for his visit—cooking a meal by the specifications that I knew would meet his standard. He arrived about ten minutes late with Matthew and left about fifteen minutes later. That was the last time I saw him for over twenty years.

The house Joyce Maynard bought in New Hampshire after her relationship with Salinger ended.

Once, when he and I were still together, in the car on the way back to Jerry’s house, he made a comment that took my sister by surprise. “I suppose you always looked up to Joyce, as younger sisters do,” he said.

That was odd. Rona was not only four years older but married, with a baby. I had even told Jerry the story of my sister’s sense of displacement at my birth. And I had just recently turned nineteen.

“Joyce is four years younger than I am, actually,” she told him quietly. “I’m twenty-three.”

“Oh well,” Jerry said, taking the BMW into fifth gear. “You’re both little girls to me.”

A thought entered my head: What if I’m getting too old for him?

One day at around this time, my mother said to me, “Your face certainly is getting round. I guess we don’t need to worry anymore about that concentration camp look of yours.”