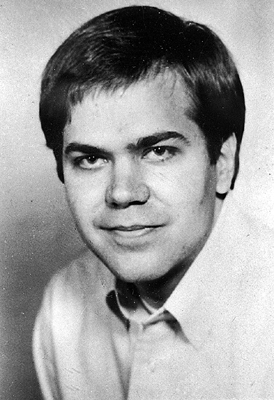

Mark David Chapman.

The Catcher in the Rye reemerges in the 1980s, misinterpreted as an assassination manual.

DAVID SHIELDS: There’s a huge amount of psychic violence in the book; Holden’s voice is full of hellacious fury. If you read the book out of neediness or desperation, you will read Holden’s antipathy to the culture as a license to kill. In the “wrong” hands, read the “wrong” way, the book’s emotional rage can become an endorsement to express your hatred toward “phonies” through violence.

Is Catcher a dangerous book? When interviewed by us, John Guare, the author of Six Degrees of Separation, said, “If one person used something I had written as the justification for killing somebody, I’d say, ‘God, people are crazy,’ but if three people used something I had written as justification, I would really be very, very troubled by it. It’s not the one; it’s the series of three.” The complicating factor in Salinger’s case—the deepening factor—is the extraordinary intimacy he creates between narrator and reader, and this intimacy is mixed with sublimated violence. He’s so good at creating a voice that seems to be practically caressing your inner ear.

It’s as if the assassins and would-be assassins who read The Catcher in the Rye are reading the book too literally. Everywhere Holden goes—Pencey, Manhattan, his parents’ apartment—he’s an utterly powerless individual. What the book shows you is how Holden comes to accept and even embrace the weakness—the brokenness—within himself, within Phoebe, within everybody. If you’re reading the book through an especially distorted lens, you feel so acutely Holden’s powerlessness that you say, “Yeah, I feel powerless, too,” and you don’t make the crucial leap that Holden finally does and Salinger always does at the end of every book and what the imaginative reader is asked to do—which is to come to see the Fat Lady as Jesus Christ himself, buddy.

—

SHANE SALERNO: In John Guare’s play Six Degrees of Separation, the protagonist, Paul, talks at length about Catcher.

JOHN GUARE: PAUL: A substitute teacher out on Long Island was dropped from his job for fighting with a student. A few weeks later, the teacher returned to the classroom, shot the student unsuccessfully, held the class hostage and then shot himself. Successfully. This fact caught my eye: last sentence. Times. A neighbor described him as a nice boy. Always reading Catcher in the Rye.

The nitwit—Chapman—who shot John Lennon said he did it because he wanted to draw the attention of the world to The Catcher in the Rye and the reading of that book would be his defense. And young Hinckley, the whiz kid who shot Reagan and his press secretary, said if you want my defense all you have to do is read Catcher in the Rye. It seemed to be time to read it again. . . .

Mark David Chapman.

I borrowed a copy from a young friend of mine because I wanted to see what she had underlined and I read this book to find out why this touching, beautiful, sensitive story published in July of 1951 had turned into this manifesto of hate. I started reading. It’s exactly as I remembered. Everybody’s a phony. Page two: “My brother’s in Hollywood being a prostitute.” Page three: “What a phony slob his father was.” Page nine: “People never notice anything.”

Then on page twenty-two my hair stood up. Remember Holden Caulfield—the definitive sensitive youth—wearing his red hunter’s cap. “A deer hunter hat? Like hell it is. I sort of closed one eye like I was taking aim at it. This is a people-shooting hat. I shoot people in this hat.”

Hmmmm, I said. This book is preparing people for bigger moments in their lives than I ever dreamed of. Then on page eight-nine: “I’d rather push a guy out of the window or chop his head off with an ax than sock him in the jaw. I hate fist fights . . . what scares me most is the other guy’s face. . . .”

I finished the book. It’s a touching story, comic because the boy wants to do so much and can’t do anything. Hates all phoniness and only lies to others. Wants everyone to like him, is only hateful, and is completely self-involved. In other words, a pretty accurate picture of a male adolescent.

And what alarms me about the book—not the book so much as the aura about it—is this: The book is primarily about paralysis. The boy can’t function. And at the end, before he can run away and start a new life, it starts to rain and he folds.

Now there’s nothing wrong in writing about emotional and intellectual paralysis. It may indeed, thanks to Chekhov and Samuel Beckett, be the great modern theme. The extraordinary last lines of Waiting for Godot—“Let’s go.” “Yes, let’s go.” Stage directions: They do not move.

But the aura around this book of Salinger’s—which perhaps should be read by everyone but young men—is this: It mirrors like a fun-house mirror and amplifies like a distorted speaker one of the great tragedies of our times—the death of the imagination.

—

JAMES YUENGER: Chapman was graduated from high school in 1973. His yearbook photo shows an apple-cheeked young man with dark hair combed over his forehead in [a] Beatle cut. For some time he had been a YMCA counselor and was well-liked. He was especially effective with young people with drug habits. He stayed on at the “Y” while he attended classes for 18 months at the local DeKalb County Junior College.

TONY ADAMS: [I remember] a guy down on one knee, helping out a little kid, or with kids just hanging around his neck and following him everywhere he went. I’ve never seen anybody who was as conscientious about his job and as close to children as he was. The kids always called him Captain Nemo. That’s what he wanted everybody to call him.

JAMES YUENGER: Too unsettled to continue in college—he was twenty and itching to wander—Chapman enlisted Adams’s help in getting a job with a YMCA student work program in Beirut, Lebanon. That, too, did not work out.

“Once he got there, he stepped into the middle of a civil war,” Adams said. “He had to stay in a shelter and he was just never able to do what he wanted to do there—work with kids.”

JACK JONES: Chapman and another young volunteer spent their days huddled under furniture while bombs, rockets, and gunfire erupted in the streets outside. The YMCA volunteers were among the first evacuated from the country. Frightened and disappointed, he returned home to Decatur where his friends recall that he spoke fearfully of the experience and played cassette tapes he had recorded of gunfire and bombs exploding in the streets outside his hotel.

JAMES YUENGER: Chapman returned from Lebanon so depressed that YMCA officials arranged for him to work in a resettlement program for Vietnamese refugees at Fort Chaffee, Arkansas.

MARK DAVID CHAPMAN: I had come off the important experience of a trip to Lebanon—the first foreign trip I’d had—and surviving in a war zone, to the success of Fort Chaffee. Then, all of a sudden, there I was at Covenant College [a Presbyterian college in Tennessee], studying hard, not knowing what on earth hit me and not knowing until this day, this morning, why I was depressed. The true reason was that I felt like a nobody. . . . I wasn’t in charge of anything. I wasn’t in a foreign country taping bomb sounds down on the avenue. . . . I was just like everybody else—a nobody.

PAUL L. MONTGOMERY: Paul Tharp, community relations director of Castle Memorial Hospital on Oahu [Hawaii], said the young man had worked at the hospital’s print shop from August 1977 to November 1979. . . . He said Mr. Chapman had left to seek work as a security guard.

Gloria H. Abe . . . was married to Mr. Chapman on June 2, 1979. . . . She worked in a travel agency in Honolulu. Mr. Chapman’s mother also lives in Hawaii and was said to have lent him money for his New York trips.

JON WIENER: Mark David Chapman was going downhill. He had a job as a security guard [in Hawaii] where he’d been seen putting Lennon’s name on a piece of tape over his own name on his uniform. He was becoming obsessed with John Lennon.

PAUL L. MONTGOMERY: On Oct. 27, Mr. Chapman paid $169 in cash for a five-shot Charter Arms revolver with a two-inch barrel at J&S Enterprises-Guns, Honolulu. The revolver is of a style that is easily concealed.

JON WIENER: He wrote to a friend, saying, “I’m going nuts.” He was clearly aware that something bad was happening to him. He quit his job and decided to let his wife support him. That didn’t make him feel any better. He was a guy who was increasingly having delusions, hearing voices, being troubled, and disturbed by the whole world around him.

J. REID MELOY: In the case of Mark David Chapman, we have an individual who had a variety of psychiatric and mental disorders. This was an individual who had a blighted life, whose father abused his mother, whose mother had a highly eroticized relationship with her son. Chapman himself did not have any whole, healthy sense of who he was.

JON WIENER: Then, in November 1980, he read Laurence Shames’s article in Esquire about John Lennon, who had been one of his heroes. As the plane lifted from the ground and banked north toward New York City, Chapman was absorbed in the magazine’s cover story, a critical and scathing commentary on the opulent life-style of sixties peacenik John Lennon.

LAURENCE SHAMES: On February 3, the Los Angeles Times let out that [Lennon] forked over $700,000 for a beachfront home in Palm Beach, Florida. In May, the New York Daily News reported that Lennon had picked up a sixty-three-foot sailboat and was mooring it on Long Island, where he also happened to own a home—this one a $450,000 gabled job in Cold Spring Harbor.

JON WIENER: Lennon was a man who represented all the hopes and dreams and utopias of the sixties. He had said, “Imagine no possessions; it isn’t hard to do.” The Esquire article was an exposé of Lennon as an over-the-hill capitalist, a rich person who had abandoned his ideals and who owned four mansions, a yacht, swimming pools, and many real estate holdings. He had tax lawyers finding loopholes for him. The theme of the article was: John Lennon is a sellout. He is a phony. This had special meaning to Chapman because he was one of the tens of millions who had read The Catcher in the Rye, and one of the things that meant the most to him in the novel was the idea of the phony, the person who isn’t what he pretends to be. That was the source of the problems in the world, as Mark David Chapman came to see it.

Part of Chapman’s mental illness was that he was very preoccupied with the evil forces in the world that were fighting the good forces. He heard voices he thought were the voices of the devil’s minions. He said he heard them inside himself—the classic paranoid schizophrenic delusion. He had tried to kill himself several years earlier. Now he read the Esquire article and conceived a new mission. Lennon was a phony, and he decided he was going to do something about it.

JAY MARTIN: Having failed to kill himself, Chapman’s identification with Lennon became more and more sinister. He projected his own suicidal wishes onto the object of his identification. Then, to kill the bad things in himself, he had to kill his double, Lennon. Once he had come to consider Lennon a phony, a betrayer of his generation’s ideals, an impostor, he decided that to kill him would be to kill his own bad side. Apparently, Chapman came to see his task as a purification of his fictions. If he could kill the phony, bad Lennon, a forty-year-old businessman who watched a lot of television and who had $150 million, a son whom he doted on, and a wife who intercepted his phone calls—that’s a description from Chapman himself—then Satan’s demons would be defeated, and as a result the world and Chapman himself would be cleansed. One last time, he called his cabinet [the delusional steering committee over which he presided] of his internal world into session and submitted to [these] little people the proposal that he kill the John Lennon impostor.

JON WIENER: John Lennon kind of withdrew from the world for four years. I see this as a time of recovery and healing from all of the turmoil and misery of this two- or three-year immigration battle. He wanted to raise his young son, Sean. And then in 1980 he went back to making music, which was something his fans had missed for a long time. The last Lennon record had come out in 1975, so it had been five years of no music. In December 1980 Lennon was back in the studio. He was recording. He released a single, “Starting Over,” that was going to be part of an album. After a period of withdrawal, Lennon was coming back.

The theme of the Esquire article was John Lennon is a sellout. John Lennon is a phony.

LAWRENCE GROBEL: And look at this guy, you know, he’s a big rock star and he comes in a limousine. Phony stuff, Chapman says.

MARK DAVID CHAPMAN: Well, he, he’s a phony.

J. REID MELOY: The word “phony” is used over thirty times in The Catcher in the Rye. . . . The word “kill” is used a lot in the book.

LAWRENCE GROBEL: You want me to teach you what reality is. . . . BANG!

—

JACK JONES: Returning to Reeves’s apartment [childhood friend Dana Reeves, a sheriff’s deputy in Henry County, Georgia], Chapman confided that he had brought a gun with him from Honolulu to New York City. He brought the gun for personal protection, he said, because he was carrying a large amount of cash and he feared being attacked and robbed on the violent sidewalks of New York. He told Reeves he had brought no ammunition from Hawaii, and explained that he had been unable to get bullets in New York. He asked Dana if he could spare a few extra shells for the gun that was still in a suitcase under the bed at his hotel . . .

Chapman refused to accept the standard, round-nosed, jacketed shells that Reeves initially offered him. He wanted something “with real stopping power,” he said, “just in case.” He selected five hollow-point Smith & Wesson Plus P cartridges designed to explode with the deadly effect of tiny hand grenades inside the soft tissue of anticipated human targets . . . just in case.

STEPHAN LYNN: Hollow-point bullets are made to explode and expand [after impact]. Chapman knew that. He knew what these bullets could do.

JON WIENER: In the future, Chapman would say he had wanted to be Holden Caulfield. That was a healthy wish. Caulfield was lonely and troubled, but he was wonderfully sane. Chapman had a moment like that when he returned to New York from going to Atlanta at the end of November. He called his wife and told her, “I’ve won a great victory. I’m coming home.” He made an appointment at the Honolulu Mental Health Clinic for November 26. He was right: that decision was a great victory, a victory of sanity over the internal forces that tormented him. But it was only temporary. He never went back to the clinic, and a week later he started hanging around in the front of the Dakota. Mark David Chapman had lost his struggle.

Chapman was staying in a place not far from the Dakota. He was reading The Catcher in the Rye. In early December 1980 he acted out the key scenes in Catcher. On the morning of December 8, he joined a group of fans waiting outside the Dakota for autographs. Everybody knew where John Lennon lived in New York City. It was known he was recording now, so it wasn’t unusual for there to be a half dozen fans waiting for him.

MARK DAVID CHAPMAN: On December 8, 1980, Mark David Chapman was a very confused person. He was literally living inside of a paperback novel, J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. He was vacillating between suicide, between catching the first taxi home, back to Hawaii, between killing, as you [Larry King] said, an icon. . . . Mark David Chapman at that point was a walking shell who didn’t ever learn how to let out his feelings of anger, of rage, of disappointment. Mark David Chapman was a failure in his own mind. He wanted to become somebody important, Larry. He didn’t know how to handle being a nobody. He tried to be a somebody through his years, but as he progressively got worse—and I believe I was schizophrenic at the time, nobody can tell me I wasn’t, although I was responsible—Mark David Chapman struck out at something he perceived to be phony, something he was angry at, to become something he wasn’t, to become somebody.

J. REID MELOY: For Chapman, The Catcher in the Rye became the instrument of the murder he would carry out. The Catcher in the Rye is a sweet book. Holden’s fantasy is to save those children. It’s not a dark fantasy; it’s not a killing fantasy. The perversion in cases [like Chapman’s] is that you pull out passages to use to give you a rationale to carry out murder. It’s important to recognize that with any narrative, if you are intent on homicide you can extract from the pages the rationale that allows you to go and kill.

Chapman traveled to New York City. He engaged in behaviors like Holden did in the book. He hired a prostitute. He met with that prostitute. But then the aggression came into play and he began to plan and carry out the act that brought him to New York City in the first place. He coveted what John Lennon had. He wanted to take that from him.

PAUL ALEXANDER: In the late morning [of December 8], Chapman greeted Lennon’s housekeeper when she took Sean for a walk, even going so far as to pat the five-year-old on the head. Double Fantasy, Lennon’s new album on which he had collaborated with Yoko Ono, had been released three weeks earlier by Geffen Records.

MARK DAVID CHAPMAN: The adult and the child got up that morning and laid out all the important things to the child: The Bible. The photo with the Vietnamese kids. The music [The Ballad of Todd Rundgren, an album by Lennon rival Todd Rundgren]. The pictures of The Wizard of Oz. The passport and the letters of commendation for my work with the Vietnamese kids. This was the child’s message, the tableau that said: This is what I was. These are the things that I was. I’m about to go into another dimension.

PAUL L. MONTGOMERY: About 5 p.m. . . . Mr. Lennon and Miss Ono left the Dakota for a recording studio. Mr. Chapman approached Mr. Lennon for an autograph . . . and he scribbled on the cover of his new album, Double Fantasy, recorded with Miss Ono and released two weeks ago.

MARK DAVID CHAPMAN: I left the hotel room, bought a copy of The Catcher in the Rye, signed it to Holden Caulfield from Holden Caulfield, and wrote underneath that “This is my statement,” underlining the word “this,” the emphasis on the word this. I had planned not to say anything after the shooting. Walked briskly up Central Park West to 72nd Street and began milling around there with fans that were there, Jude and Jerry, and later a photographer that came there. . . .

[Lennon] was doing an RKO radio special, and he came out of the building and the photographer . . . Paul Gores, he kind of pushed me forward and said, here’s your chance. You know, you’ve been waiting all day. You’ve come from Hawaii to have him sign your album. Go, go.

And I was very nervous and I was right in front of John Lennon instantly and I had a black, Bic pen and I said, John, would you sign my album. And he said sure. Yoko went and got into the car, and he pushed the button on the pen and started to get to it write. It was a little hard to get it to write at first. Then he wrote his name, John Lennon, and underneath that, 1980.

And he looked at me . . . he said, is that all? Do you want anything else? And I felt then and now that he knew subconsciously that he was looking into the eyes of the person that was gonna kill him.

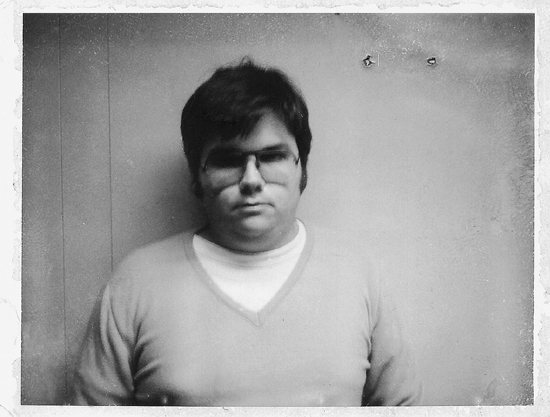

PAUL L. MONTGOMERY: A newspaper reproduction of a picture [of the encounter] taken by a freelance photographer [Gores] shows Mr. Chapman with tousled hair and wire-rim glasses, wearing a dark raincoat and a scarf.

Mark David Chapman.

JAY MARTIN: Chapman urged the photographer to remain on the scene until Lennon returned. “You never know,” he said. “Something might happen.” The photographer left, but Chapman stayed.

PAUL ALEXANDER: At one point, Chapman returned to his hotel room, where he had left his autographed copy of Double Fantasy. He then returned to the Dakota.

JON WIENER: Eventually, Lennon’s car came back with John and Yoko in it. Chapman was waiting outside.

PAUL L. MONTGOMERY: The Lennons returned to the Dakota at about 10:50 p.m., alighting from their limousine on the 72nd Street curb although the car could have driven through the entrance and into the courtyard. . . . Three witnesses—a doorman at the entrance, an elevator operator and a cab driver who had just dropped off a passenger—saw Mr. Chapman standing in the shadows just inside the arch. . . .

MARK DAVID CHAPMAN: John came out, and he looked at me, and I think he recognized, here’s the fellow that I signed the album earlier, and he walked past me. I took five steps toward the street, turned, withdrew my Charter Arms .38, and fired five shots into his back. . . . Before, everything was like dead calm. And I was ready for this to happen. I even heard a voice, my own, inside me say, do it, do it, do it. You know, here we go.

PAUL L. MONTGOMERY: As the couple walked by, Chief Sullivan said Mr. Chapman called, “Mr. Lennon.” Then, he said, the assailant dropped into “a combat stance” and emptied his pistol at the singer.

Mr. Lennon staggered up six steps to the room at the end of the entrance used by the concierge, said “I’m shot,” then fell face down.

MARK DAVID CHAPMAN: Afterwards, it was like the film strip broke. I fell in upon myself. I like went into a state of shock. I stood there with the gun hanging limply down at my right side and José the doorman came over and he’s crying, and he’s grabbing and he’s shaking my arm and he shook the gun right out of my hand, which was a very brave thing to do to an armed person. And he kicked the gun across the pavement, had somebody take it away and I was just—I was stunned.

JAY MARTIN: Immediately following the shooting, Chapman calmly removed his coat and sweater—apparently so the police, when they arrived, would see that he was unarmed and intended no further harm—and took his copy of The Catcher in the Rye and read with intense concentration. . . . To have the book with him—he was right there with J. D. Salinger, right there with Holden.

—

STEPHEN SPIRO: I was a police officer in the Twentieth Precinct. I was in a radio car at approximately 10 minutes till 11 on the evening of December 8 when my partner, Peter Cullen, and I pulled up to the Dakota. There was a man standing out in the street, pointing into the archway, saying, “That’s the man doing the shooting!” I got out of the car, drew my gun, and proceeded to walk up against the side of the building until I saw a man standing there with his hands up. It was very dimly lit, but because he had his hands up and the shirt he was wearing was white, I saw right away he didn’t have a gun. I proceeded, trying to size up what was happening. I walked in, grabbed the man around the shoulders, and switched them around so his back was to me and I had my arm around his neck, because I thought maybe there were more shooters; maybe they were robbing somebody in the Dakota.

At that point I turned to my right and saw a gentleman who I knew as the doorman, José. José said, “He’s the only one.” I looked at the guy I had and threw him up against the wall. Just as I was doing this, José yelled out, “He shot John Lennon! He shot John Lennon!” I said, “Oh, my God.”

I said to the guy, “You did what?” He said, “I acted alone.” I thought, “That’s the strangest statement I’ve ever heard.” I pushed him against the wall and handcuffed him as my partner came in behind me.

There were other police officers responding to the scene and they had run into the vestibule, where they found John Lennon bleeding to death. They picked him up—two of them, Herbie Frownberger and Tony Palmer, who were both weightlifters. When I turned around, I saw them carrying John Lennon at shoulder height. His eyes were closed and blood trickled out of the side of his mouth. Right away, when somebody is face up and blood is coming out of his mouth, you know his lungs are filled up with blood. It was obviously a serious wound. I knew they must have decided they could get him to Roosevelt Hospital faster than an ambulance could. Maybe they could save his life that way.

DAVID SHIELDS: Lennon was carried into the squad car of officers Bill Gamble and James Moran and driven to Roosevelt Hospital about a mile away.

PAUL L. MONTGOMERY: Officer Moran said they stretched Mr. Lennon out on the back seat and that the singer was “moaning.” [Officer Moran] said he had asked, “Are you John Lennon?” and Mr. Lennon had moaned, “Yeah.”

STEPHEN SPIRO: I stood at the Dakota in amazement. I had the guy against the wall—later I’d find out his name was Mark David Chapman—and he was saying, “Don’t hurt me!”

I said, “Nobody’s going to hurt you. We’re going to take you down to the stationhouse.” I looked on the ground and said, “Are these your clothes?” He had taken off his outer garments to make sure it was noticeable he was wearing white. He was only 500 feet from a subway station. He could’ve run away and been gone in a matter of seconds. It was clear he wanted to stay there.

“Are these your clothes?” I said. He said, “Yes, and the book is mine, too.” The book was The Catcher in the Rye. I picked it up. I told him we would take it along with his clothes.

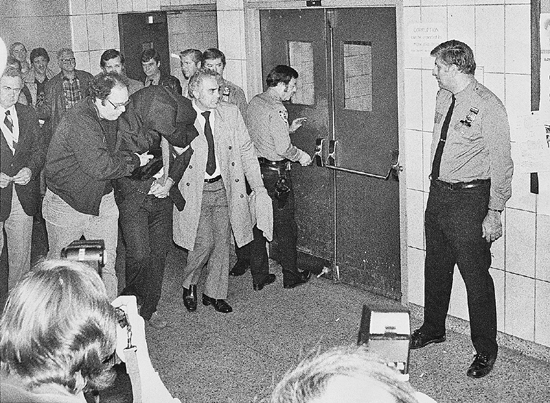

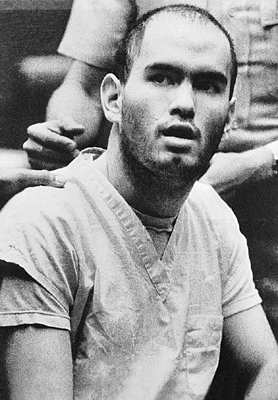

Mark David Chapman being arrested; on his right, NYPD officer Stephen Spiro.

When we got him to the stationhouse, we took him to a detention cell, where we did a strip search to make sure he had no more weapons on him. At that time, we found out he was from Hawaii and he was wearing thermal underwear when it was 50 degrees outside. When I looked inside the book, he had written, “This is my statement.” I didn’t understand what that meant at the time.

—

STEPHAN LYNN: I arrived at the emergency room before the patient. The chief surgical resident was standing there when the patient rolled in. He didn’t come in by ambulance; the police actually carried the patient into the room.

We rushed into the trauma room. We took off his clothes. There were three wounds in the left upper chest and one through the left arm. There was no blood pressure, no pulse, no vital signs, no response. We knew exactly what we had to do: IVs, blood transfusions, surgical procedure in the emergency department. We opened the chest to look for the source of the bleeding. In the process, the nurses took the wallet out of the pocket of the patient. They said, “This can’t be John Lennon.” We realized it was when Yoko Ono came into the emergency room.

When we opened the chest, we saw there was a tremendous amount of blood. Those three bullets destroyed the vessels leading out of the heart, cut them to bits. We tried. We gave him blood. We pushed on the vessels that were broken. I literally held his heart in my hand. We massaged his heart, but it was empty. There was no blood in it. We tried to get the heart started again. There was nothing we could do. After about 20 minutes, we declared John Lennon dead. When we were done, the nurses, I, everybody in the emergency room, stopped for a second to realize what had happened and where we had been.

My next task was to speak to Yoko Ono. David Geffen was with her. I said, “I have bad news for you. He’s dead, in spite of all of our efforts.” Yoko refused to believe it. She said, “No! It’s a lie! It can’t be. You’re lying to me. It can’t be true. Tell me he’s not dead.” But after about five minutes, she understood. The first thing she said after that was, “Doctor, please don’t make the announcement for 20 minutes so I can go home and see Sean and tell him what’s going on.”

—

RICHARD STAYTON: I was in a restaurant, having a steak, watching Monday Night Football. I remember Howard Cosell interrupting the game by saying, “Sometimes events change the way you see your life, and why are we watching this game? The game doesn’t matter. John Lennon has been murdered.” Frank Gifford said, “John Lennon?” Everybody where I was sitting said, “John Lennon? You got to be kidding.” It was the blow I felt when I heard Robert Kennedy was shot and murdered, but I felt closer to John Lennon than I felt when RFK or JFK was killed.

MARK DAVID CHAPMAN: I never wanted to hurt anybody, my friends will tell you that. I have two parts in me. The big part is very kind. The children I work with will tell you that. I have the small part in me that cannot be understood. . . . I did not want to kill anybody and I really don’t know why I did. I fought against the small part for a long time. But for a few seconds the small part won. I asked God to help me but we are responsible for our own actions. I have nothing against John Lennon or anything he has done in the way of music or personal beliefs. I came to New York about five weeks ago from Hawaii and the big part of me did not want to shoot John. I went back to Hawaii and tried to get rid of my small part but I couldn’t. I then returned to New York [on December 6, 1980, after leaving Honolulu] on Friday, December 5, 1980. I checked into the YMCA on 62nd Street. I stayed one night. Then I went to the Sheraton Centre 7th Ave. Then this morning I went to the bookstore and bought The Catcher in the Rye.

I’m sure the large part of me is Holden Caulfield who is the main person in the book. The small part of me must be the Devil. I went to the building; it’s called the Dakota. I stayed there until he came out and asked him to sign my album.

At that point my big part won and I wanted to get back to the hotel, but I couldn’t. I waited until he came back. He came in a car. Yoko walked past me first and I said hello. I didn’t want to hurt her. Then John came, looked at me and printed me. I took the gun from my coat pocket and fired at him. I can’t believe I could do that. I just stood there clutching the book. I didn’t want to run away. I don’t know what happened to the gun, I just remember José kicking it away. José was crying and telling me to please leave. I felt so sorry for José. Then the police came and told me to put my hands on the wall and cuffed me.

STEPHEN SPIRO: What confuses me is these people follow this book like it’s the bible for achieving something in life, when this kid was a mixed-up adolescent visiting New York City and fantasizing about certain things. I don’t think J. D. Salinger ever meant for anybody to hurt somebody with his thoughts. Mark David Chapman portrays himself as the catcher in the rye to stop children from jumping over the cliff after they run through the field of rye and he’s going to stop them and be their savior. Well, I don’t see how that equates to him killing people.

DAVID SHIELDS: After being charged with second-degree murder, Chapman decided in January 1981 to use his trial to broadcast his interpretation of The Catcher in the Rye. Chapman told his attorney, Jonathan Marks, that God told him to plead guilty. Two weeks later, on June 22, Judge Dennis Edwards questioned Chapman at the start of the trial and found him to be of sound mind. Edwards accepted the guilty plea and sentenced Chapman to twenty years to life on August 24.

Courtroom sketch of Mark David Chapman, who stated that his defense can be found in The Catcher in the Rye.

STEPHEN SPIRO: Mark David Chapman wrote me a letter that I should read Catcher in the Rye to understand why he committed this murder.

MARK DAVID CHAPMAN, excerpt from letter to Stephen Spiro, January 28, 1983:

The reason I wanted to write you was that from the time of my arrest I have felt close to you. It is something that would happen to Holden Caulfield. If you are familiar with him and The Catcher in the Rye, please reread the book. It will explain a lot of what happened on the night of December 8th. To answer your question of what was meant by “This is my statement,” the only way I can explain it is this way. Do you remember the young woman in Saigon during the Vietnam War who immolated herself? I believe her name was Nhat Chi Mai. She believed so strongly in the purpose that she chose to end her life rather than continue living in the phony world. The damn war did this to her. What a noble lady. Poems were found on her and around her concerning her beliefs. This was her statement to leave to the world. Catcher in the Rye is my statement. The book is incredible.

JAY MARTIN: A dramatic moment occurred in the court when the judge, before sentencing, asked Chapman if he had anything of his own he wanted to tell the court that might influence the sentencing. Perhaps it would explain why he did what he did. Chapman said, “Yes.” He was going to have a vow of silence, but first he would speak and speak from his heart. God allowed him to become Holden Caulfield and to speak Holden’s words. He had killed phoniness. He had murdered evil. He had rid the world of death. He was the catcher in the rye.

So when Chapman spoke, his words came directly from The Catcher in the Rye, only he recited them as if they were his own words and as if they expressed the precise position at which he personally had arrived. “I kept picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids. And nobody’s around, nobody big, I mean, except me. And I’m standing at the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff. I mean, if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going, I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I’d do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all. I know it’s crazy, but that’s the only thing I’d really like to do.” That’s the only thing Chapman wanted to do—to become Holden Caulfield. He acted the passage out as if he were Holden Caulfield because he believed he was. Those were his last words in the court.

Chapman’s final testimony amounted to this: He himself had ceased to exist. In a letter to his wife, he stated that this was so. He no longer existed in his own being. He had found his true being in Salinger’s novel.

Chapman took from Holden the opposite of freedom. He identified so extremely that the identification became self-sustaining, because it gave him a self that he didn’t possess before. He had to do what Salinger didn’t do and what Holden himself didn’t do: go with it fully. Catcher in the Rye is not meant to be a dangerous book. It’s meant to be a curative book.

MARK DAVID CHAPMAN, excerpt from letter to Stephen Spiro, January 15, 1983:

Have you read The Catcher in the Rye? I know this will help you to further understand, to answer your questions. The Catcher in the Rye is the statement. I probably forgot to tell you that I underlined the word “This,” so it read “This is my statement,” meaning the book itself. Did you ever see what I sent to the New York Times on February 9, 1981? [The newspaper published a letter written by Chapman.] This further explains what happened on the night of December 8, 1980. I will let you decide whether Mr. Lennon was a phony or not. His own words shot his life purpose full of holes. If you dig deep and not idolize, it is all there. Yes, Lennon was a phony to the highest degree and there were others who could and would have served the same purpose.

J. REID MELOY: Holden Caulfield was not an assassin. Yet with his psychopathology, Mark David Chapman was able to twist that book and extract from it a narrative he could identify with that led him somehow to assassinate John Lennon. Chapman came to believe that he was the Holden Caulfield of his generation and that he could save his generation. That is pure grandiosity—what is referred to as pathological narcissism, where you become a legend in your own mind. There was an aggression tied to that narcissism that gave him the drive and the means and the motivation to kill.

JAY MARTIN: Salinger certainly had no intention with Catcher of anything other than writing a good book—a book that, he said, needed to be written. The effect of what Salinger did in placing his own distress into a character was to make that character available to millions of people. Of those many millions, maybe a few will take it more seriously, more dramatically, than a normal reader, who will simply say, “That’s an interesting book.”

—

MARK DAVID CHAPMAN: So it didn’t end with the death of John Lennon and that’s, you know—you keep paying for this over and over when you hear of the death of a celebrity and maybe they’ve got The Catcher in the Rye, as John Hinckley did.

John Hinckley, who, under the influence of The Catcher in the Rye, attempted to assassinate President Ronald Reagan.

JOHN GUARE: Yes, The Catcher in the Rye is a wonderful book for adults to read about a certain time of life. But it also gives validity to fifteen-year-olds to say, “I am the only thing on this planet and you are all worthy of annihilation because you’re all phony.” I use it in Six Degrees of Separation because the play asks the question: Is this young man [Paul] authentic or false? And Catcher in the Rye embodies the conflict between what is true and what is false.

DINTY MOORE: Across from the Dakota that evening [of Lennon’s murder], thousands of mourners began immediately to congregate. Among them was John Hinckley Jr. Hinckley had seen the movie Taxi Driver—fifteen times—and had begun to imitate Travis Bickle’s preference for fatigue jackets, army boots, and peach brandy. He also developed an obsession with Jodie Foster, the child-prostitute in the film, and began to stalk her.

JACK JONES: The list of ingredients on Hinckley’s murder recipe, like Chapman’s and [Robert] Bardo’s [who later killed the actress Rebecca Schaeffer], included a .38 caliber Charter Arms Special and a copy of The Catcher in the Rye.

JAY MARTIN: Chapman’s in the papers. He’s being shown on TV. He’s a character as much as Holden. And so you copycat him. So you go ahead and look at Catcher in the Rye and you say, “That’s how I’ll become John Hinckley, by becoming Mark David Chapman and by becoming Holden Caulfield, and eventually it might be by reading J. D. Salinger.”

DINTY MOORE: Hinckley settled on assassination as his best strategy to win Foster’s heart, and on March 30, 1981, fired six times at President Ronald Reagan outside of the Hilton Hotel in Washington, DC. In Hinckley’s hotel room, police found a John Lennon calendar and a paperback copy of The Catcher in the Rye.

CYRUS NOWRASTEH: When Reagan left the luncheon, he walked out of the hotel. There was a very small group of people waiting to see him, cordoned off by some tape, and John Hinckley was waiting in the group. In fact, he had been there when the president arrived and had wandered around outside the hotel; he had gone inside and come back out. He may have been debating with himself whether he was really going to go through with it.

Something within Hinckley clicked when Reagan emerged from the luncheon, and he pulled the trigger.

J. REID MELOY: John Hinckley talked about how he wanted to be linked forever with Jodie Foster—which, through this act of attempting to assassinate Ronald Reagan, he has. In the minds of many people, he’s linked with her, and it’s unlikely she’ll ever forget the name “John Hinckley.”

CYRUS NOWRASTEH: Why repeat the same story? With Hinckley, you’ve got a much sexier cast: it’s Jodie Foster, Taxi Driver, De Niro, Scorsese, people the media can hound and show clips of, and that’s much more immediate than this book, which they’d already covered as the foundation to events.

—

ROBERT D. McFADDEN: A teacher’s aide dismissed recently after a fight with a student returned to a Long Island school yesterday, wearing military fatigues and carrying a rifle, shot the youth and the principal, and took 18 students hostage.

Nine hours later, after releasing 17 hostages unharmed in groups and singly through the day and the evening, the gunman, 24-year-old Robert O. Wickes, fatally shot himself in the right temple.

JAMES BARRON: Mr. Wickes was calm, never pointed the gun at the hostages and tried to soothe them when they became nervous. He freed the students who were most uneasy and kept the calmest ones with him the longest. He even consulted some of the students before firing shots.

“He asked me if it was O.K. if he shot a few rounds at the map,” Bryant [a student] said. “He was very polite. I said, ‘Please, no, I get too nervous at guns.’ ”

Inside the second-floor social studies classroom, with a garbage can atop the teacher’s desk to hide behind and shoot if the police stormed the room, Mr. Wickes told the students over and over that he trusted no one and that his dog, Goalie, was his only friend.

Nancy DeSousa, Mr. Gonzalez’s daughter, noted Mr. Wickes’s recent interest in Judaism and said he had been studying Hebrew. He talked of going to Israel, she said. “Bobby was very interested in everything, everything,” she said. “He just was very intelligent.”

Mrs. DeSousa spoke of his love for J. D. Salinger. “Bobby always carried around Catcher in the Rye—it was like his Bible,” she said. “He was more thoughtful than the average boy his age. There’s a deep story here. It’s not just a mad killer with a gun.”

—

MARCIA CLARK: During 1989 Robert Bardo had been communicating with Rebecca Schaeffer, sending postcards and letters for quite some time. Initially he wrote to her that she was someone he admired, someone who was not the usual Hollywood starlet type. She responded only twice, with postcards that were very neutral, very nice—thank-you-for-your-support kind of thing—and nothing more. There was nothing personal, nothing that seemed inappropriate at all.

Robert Bardo, who, under the influence of The Catcher in the Rye, killed the actress Rebecca Schaeffer.

J. REID MELOY: What Schaeffer didn’t know was that Bardo had actually come to Los Angeles on a couple of occasions to look for her, driving around the Hollywood Hills because he had read in an article in TV Guide that she lived in the Hollywood Hills and he thought that by just driving around on the streets he would find her. He had come to the Warner Bros. ranch where she was shooting [the television show] My Sister Sam and made contact with the security guard there. Bardo had chocolates and a big teddy bear for her, but the security guard told him, “You’re not going to get to see her and you really ought to go home.” The guard tried to counsel him and actually drove him back to the bus station because he thought he was harmless, a lonely kid who was in love with a star but who would never be seen or heard from again.

On July 18, after he had paid a private investigator in Tucson $250 for Schaeffer’s address, Bardo came to her neighborhood with what could be termed his assassination kit: a CD, a gun, a bag, and a copy of The Catcher in the Rye.

STEPHEN BRAUN and CHARISSE JONES: From his parents’ house in a treeless, sun-parched subdivision in Tucson, Robert John Bardo wrote letter after letter to actress Rebecca Schaeffer, missives to another world.

Scrawled shakily in pen, the letters were Bardo’s way of reaching out from the boredom and insignificance of his young life. At 19, a janitor at a succession of hamburger stands, he was on the cusp of manhood, but going nowhere.

Bardo detailed his chaste devotion to the fresh-faced young woman who appeared to him only when his television set glowed. He quoted John Lennon lyrics. He told her he was “a sensitive guy.” In one passage, he explained: “I’m harmless. You could hurt me.”

Just before his journey to Los Angeles, he wrote his sister in Knoxville, Tenn., saying: “I have an obsession with the unattainable and I have to eliminate (something) that I cannot attain.”

ASSOCIATED PRESS: The star of the television series “My Sister Sam” was shot to death outside her apartment here Tuesday, and a man described as “an obsessive fan” was being held today in Arizona in the shooting.

California authorities filed a felony arrest warrant today for the man, Robert John Bardo, 19, of Tucson, Ariz., a former fast-food restaurant worker who was arrested by Tucson police earlier today for running in front of cars.

STEPHEN BRAUN and CHARISSE JONES: Later, acting on information supplied by Bardo, police would find a gun holster in the alley just south of and parallel to Beverly Boulevard. A yellow shirt was found on the roof of a cleaners. And on the roof of a rehabilitation center came a final piece of evidence—a red paperback copy of the novel The Catcher in the Rye.

—

J. REID MELOY: It’s important to remember that these three males—Chapman, Hinckley, and Bardo—were all in their early to mid-twenties when they did what they did. It takes a young male’s aggression to carry out an act of assassination. These individuals are not just pursuing a celebrity figure; they are intent on killing the celebrity figure. We know murder is an act of young men.

If you are driven by homicidal urges, if you have a desire to kill certain figures, the book becomes a rationale for your killing and for the planning of that assassination. Holden Caulfield feels emotionally impotent. Chapman, Hinckley, and Bardo felt emotionally impotent. The gun became the equalizer. The gun brought potency to these young men, for a moment, through their assassinations.

MICHAEL SILVERBLATT: Let’s examine the record: The diary purported to be by [Arthur] Bremer, who shot George Wallace [a copy of The Catcher in the Rye was found in Bremer’s Milwaukee apartment after the shooting], contains references to Dostoevsky, especially to Raskolnikov [the main character and murderer in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment]. Dostoevsky is thought to be a big inspirer of assassins and bomb throwers—who knows why I find it easier for people to think of Dostoevsky than J. D. Salinger as a terrorist tutor? You’re talking about a very particular kind of assassin, someone who feels neglected and lost, and I do think that Salinger is a great romantic about loneliness, about not being loved or wanted, about not being able to figure out how to move on.

What could be more beautiful? Who didn’t want a masked avenger to protect you if you were the pimply guy whom no one wanted to talk to or who wasn’t let into the room when the clique was meeting? In Salinger’s very last published work [“Hapworth 16, 1924”], Seymour Glass is telling his family that they have superpowers. Buddy can read and memorize an entire novel in twenty minutes. They’re a family of superheroes, and they’re warned not to tell the librarians and teachers about their ability. These characters clearly are on earth to rescue the rest of us.

HENRY GRUNWALD: The discussion can easily become obsessive and excessive. Perhaps we should all observe a moratorium on Salinger talk. But we won’t, and [the literary critic] John Wain has explained why not. Wain dislikes “Seymour” for all the usual reasons, and in fact suggests rather plaintively that Salinger brutally maltreats his readers in that story. But, he admits, “We won’t leave. We stay, rooted to the spot. [We’re] not in a position to go elsewhere. Because no one else is offering quite what Mr. Salinger is offering.”

MARK DAVID CHAPMAN: I’m not blaming a book. I blame myself for crawling inside of the book and I certainly want to say J. D. Salinger and The Catcher in the Rye didn’t cause me to kill John Lennon. In fact, I wrote to J. D. Salinger, I got his box number from someone, and I apologized to him for this. I feel badly about that. It’s my fault. I crawled in, found my pseudo-self within these pages . . . and played out the whole thing. Holden wasn’t violent, but he had a violent thought of shooting someone, of emptying a revolver into this fellow’s stomach, someone that had done him wrong. He was basically a very sensitive person and he probably would not have killed anybody, as I did. But that’s fiction, and reality was standing in front of the Dakota.

John Lennon wasn’t the only person to die because of this. . . . Robert Bardo wrote me three letters. I don’t have them anymore. I tore them up. They were very deranged letters. . . . I got frightened.

DAVID SHIELDS: During a period of four months, a world-famous musician/political activist was killed and the president of the United States was nearly killed, winning admiration for uttering the movie-like line, “I should have ducked.” Both John Hinckley and especially Mark David Chapman cited The Catcher in the Rye as an influence. Salinger drove into Windsor, Vermont, every day to pick up the New York Times, which his letters indicate he read carefully. A large satellite dish was attached to his house; he watched quite a lot of television, including the news. In late 1980 and early 1981 he must have been inundated with information about the role his iconic novel played in these two traumatic events, about which he never made a public comment. Maybe he felt found out. Maybe he thought Chapman and Hinckley had gotten the blood-soaked violence buried within the pages of his beautiful book. Reportedly, in 1979 he pulled back a story—already in galleys—from the New Yorker at the last minute. He never published another story or book, never even came very close, and it’s difficult to believe Chapman and Hinckley weren’t forever standing guard at the gates of his imagination.

ETHEL NELSON: I remember seeing Jerry a week or so after John Lennon was murdered. Jerry was walking the streets alone, head down. I said hi to him and he walked by without even saying hi. And I knew him since 1953.