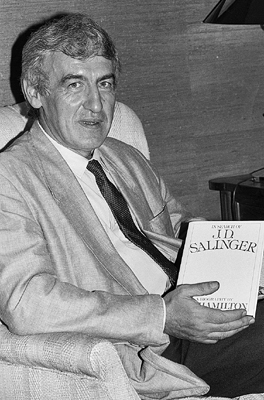

Ian Hamilton, the author of In Search of J. D. Salinger.

For the past two decades [1966–86] I have elected, for personal reasons, to leave the public spotlight entirely. I have shunned all publicity for over twenty years and I have not published any material during that time. I have become, in every sense of the word, a private citizen.

J. D. Salinger

DAVID SHIELDS: Salinger spent 1950–80 crafting a myth. He will spend 1980–2010 fighting to control, protect, and defend that myth. He’s in a defensive crouch—battling his daughter, his former lover, his would-be biographer. He loves to hate them, to see in them only ego. He’s partly right: the world provides minute-by-minute proof of human corruption. But in Salinger’s flexible moral compass, his nonabsolute absolutism, one can see ego as well. This contradiction doesn’t sit well with the Salinger purity narrative, and so he moves to quash rumors of his human foibles, anxiously managing his image while pretending to be above any such base considerations. Salinger is a man hungrily alive to the sound of his own righteousness. His message to Ian Hamilton, Joyce Maynard, and Margaret Salinger: “I don’t know who you are,” which for him is the definition of oblivion. Complicating irony: in his zeal to save himself, he destroys himself—his reputation, his writing life, his relationships with friends, loved ones, family members.

—

S. J. PERELMAN: [After a visit to Martha’s Vineyard] I ended up spending a night with Jerry Salinger, up on the Vermont border, in his aerie. We hadn’t seen each other for six years, and I’m glad to report that he looks fine, feels fine, and is working hard, so you can dispel all those rumors, manufactured in Hollywood by the people to whom he won’t sell Catcher in the Rye, to the effect that he has taken leave of his senses.

ANDREAS BROWN: Through the years, Salinger would come into the store five or six times a year, usually with his son. He normally made a beeline for the philosophy/religion alcove, and if Mrs. Steloff, who founded our store, was in, he’d sit and talk with her for a considerable length of time. His demeanor in our store was this: If he needed something, he would talk to the staff. We treated him offhandedly, as if he was nobody, because that’s the way he wanted to be treated. We would help him, quote books for him we thought he might be interested in, and search for books for him on occasion. But if a fan came up to him and wanted to strike up a conversation or wanted him to sign something or talk to him, he would excuse himself and almost always leave the store. People would always want him to explain why Holden Caulfield did something in chapter seven—that sort of thing. Or they’d ask him what he meant by something in Franny and Zooey. They’d be playing college sophomore. Then again, more than one generation has grown up with Salinger.

The first time he brought in Matt, I thought to myself, “That’s Holden Caulfield, he’s stepping right off the paperback,” because Matt had his baseball cap sideways or backwards at a time when kids didn’t wear baseball caps that way. This little kid came into the store looking just like that, and he’d be completely disinterested in what his father was doing. He’d find the cartoon books. He could sit on the floor for hours looking at Charles Addams.

CATHERINE CRAWFORD: One example of the lengths that fans will go to get Salinger’s attention was when a number of high school kids devised this elaborate plan, and they actually threw one of their friends out of a car. They drove by his house, and they had covered the kid in ketchup to make him look bloody and he landed on the ground outside of Salinger’s house, moaning, rolling around. Salinger came to the window, took one look and knew it was fake, so he shut the blinds and went back to work.

DAVID SHIELDS: In 1981 Elaine Joyce, one of the stars of Mr. Merlin, a sitcom, received a fan letter from Salinger—the same M.O. he followed with countless other young, talented, beautiful women. A correspondence ensued.

PAUL ALEXANDER: As he had with Maynard, Salinger eventually arranged for [himself and Elaine Joyce] to meet. Subsequently a relationship developed. They spent a lot of time in New York. “We were very, very private,” she says, “but you do what you do when you date—you shop, you go to dinner, you go to the theater. It was just as he wanted it.” In May 1982, when the press reported Salinger showing up for an opening night at a dinner theater in Jacksonville, Florida, where Joyce was appearing in the play 6 Rms Riv Vu, to conceal their affair she denied knowing him. “We were involved for a few years through the middle eighties,” Joyce says. “You could say there was romance.” Eventually the romance ended and, ironically enough, she moved on to marry the playwright Neil Simon.

SHANE SALERNO: After his brief relationship with Elaine Joyce, Salinger dated Janet Eagleson, who was much closer to Salinger’s age than most of the women he dated.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Janet Eagleson, August 9, 1982:

The more I age, senesce, the more convinced I am that our chances of getting through to any intact sets of reasons for the way things go are nil. Oh, we’re allowed any number of comically solemn assessments—the burning of “Rosebud” the adored sled, or, no less signally, the burning of the new governess’s backside—but all real clues to our preferences, stopgaps, arrivals, departures, etc., remain endlessly hidden. The only valid datum, anywhere, I suspect, is the one the few gnanis adamantly put forward: that we’re not who or what we thing [sic] we are, not persons at all, but susceptible to myriad penalties for thinking we’re persons and minds. . . .

I’m o.k., I think, and so is Matthew, thanks for asking. He’s in California, at the moment. Talking to actors’ agents, etc. My other kid, Peggy, is off to Oxford for two years, on some sort of academic scholarship. She and her mother are looking rather exalted about it. Exemplary achievers, both of them, mother and daughter.

MYLES WEBER: In 1982 an aspiring writer named Steven Kunes submitted an interview with J. D. Salinger to People. The magazine prepared to publish it. Salinger caught wind of the hoax, brought suit against Kunes, and stopped publication of the interview.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Janet Eagleson, August 9, 1982:

I’m in the middle of some legal action, irritating and wearying, and probably hopeless. Meaning that no sooner is one opportunist and parasite dealt with than the next guy turns up. Some prick took out a whole page ad in the Sunday Times Book Section pretending it was me or my doing. It, too, shall pass, no doubt, as Louis B. Mayer once said, but it would be nice to know when.

THE NEW YORK TIMES: According to the suit, Mr. Kunes “offered for sale to People magazine a completely fictitious ‘interview’ with J. D. Salinger” and misrepresented it as “a transcript of an actual interview.” “The fraudulent interview,” the suit adds, “grossly distorts and demeans the plaintiff’s character, it misrepresents the plaintiff’s opinion, and it falsely imitates his style.”

JOHN DEAN: My immediate reaction was: this is another scam like the Howard Hughes book, when Clifford Irving pretended to have Howard Hughes’s permission. Salinger put it to sleep very quickly when he filed a lawsuit and prohibited People from using the interview.

ASSOCIATED PRESS: A settlement has been reached in a suit filed by J. D. Salinger against a New Yorker he accused of impersonating him and passing off his writings as those of the novelist and short-story writer.

Judge David N. Edelstein of the United States District Court approved the settlement in which the defendant, Steven Kunes of Manhattan, agreed to be permanently enjoined from representing by any means that he is associated with or ever met Salinger.

The agreement also barred Mr. Kunes from exhibiting, transmitting or distributing documents, writing or statements attributed to Mr. Salinger. Mr. Kunes is also required to collect and turn over any such documents or writing for destruction. Mr. Salinger, in turn, agreed to withdraw his claims for monetary damages and legal costs.

—

MARC WEINGARTEN: Ian Hamilton was a very respected British biographer. He had written a biography of Robert Lowell that was quite well received. Hamilton was known for heavily leaning on letters in his biographies. He decided that he was going to tackle the biographer’s dream project: a book about Salinger. His big mistake was obtaining a cache of Salinger’s letters and using them as the narrative spine of the book.

IAN HAMILTON: Four years ago [in 1983], I wrote to the novelist J. D. Salinger, telling him that I proposed to write a study of his “life and work.” Would he be prepared to answer a few questions? . . . I assured him that I was a serious “critic and biographer,” not at all to be confused with the fans and magazine reporters who had been plaguing him for thirty years. . . . All this was, of course, entirely disingenuous.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Ian Hamilton, undated:

You say you’ve been commissioned by Random House to write a book about me and my work (you put it, perhaps undeliberately, in just that order), and I have no good reason to doubt your word, I’m exceedingly sorry to say. . . . I’ve despaired long ago of finding any justice in the common practice. Let alone any goodness or decency.

Speaking (as you may have gathered) from rather unspeakably bitter experience, I suppose I can’t put you or Random House off, if the lot of you are determined to have your way, but I do feel I must tell you, for what very little it may be worth, that I think I have borne all the exploitation and loss of privacy I can possibly bear in a single lifetime.

SHANE SALERNO: There had been dozens and dozens of books and articles about Salinger’s work; this threatened to be the first book to examine his life, which is what unnerved him.

PHOEBE HOBAN: Salinger’s letter to Hamilton brought up a good point: apart from a criminal, nobody comes under as much scrutiny as the subject of a biography.

Jason Epstein [Hamilton’s editor at Random House] wrote back to Salinger, saying that he was indeed a worthy and suitable subject for a biography, that he was a public figure, and that a biographer had a right to explore his life and work.

Ian Hamilton, the author of In Search of J. D. Salinger.

SHARON STEEL: [In a letter to Michael Mitchell,] Salinger has “murder in my heart” because a “sore English prick,” otherwise known as Ian Hamilton, has been digging around for material for a biography of the author’s life, commissioned by Random House. . . .

[In a December 25, 1984, note to Mitchell written on the back of a Christmas card,] Salinger seems particularly depressed and detached, and hell-bent on hiding it. He writes of visiting London to see Peggy over the holiday, who, by some miscommunication, went to Boston. So Salinger decided to knock around the city alone. “I feel closed off from all general or personal conversation, these years, and consort with almost no one but one or two local drunks or distant madwomen.” He’d rather not do anything unless it involves the writing he’s working on. Salinger wishes Mitchell “intactness and sanity” for 1985.

—

JOHN DEAN: The U.S. law for letters is not unlike England’s common law: a letter has really two aspects. One is the physical aspect of the letter and the other is the content of the letter. The person who receives the letter owns the physical possession of the letter but not the content of the letter by the author. The author retains the copyright. Only the physical letter can be sold. Salinger’s lawyers notified Hamilton of their client’s displeasure with his use of Salinger’s letters in the galleys of Hamilton’s biography. They argued that Hamilton’s use of the Salinger letters would prevent Salinger from using them for his own commercial use at some future point. They demanded that Hamilton take the letters out of the book. Hamilton tried to appease Salinger by paraphrasing from the letters. But Salinger wasn’t happy with the paraphrasing, sued, and was issued a temporary restraining order on the book by a New York district court.

PHOBE HOBAN: [Hamilton] just used his thesaurus to come up with synonyms. Instead of having Salinger’s beauty and elegance of language and original cadence, he came up with these heavy-handed, awkward, clumsy, hideous parodies of Salinger’s sentences that anybody would’ve been injured and insulted by.

JOHN DEAN: Salinger said, “No. This is not acceptable. I’m not happy with your modification, and we’re going forward with this [lawsuit].” There’s nothing private about a lawsuit. It’s probably the most exposed way you can go, because discovery is open, and [Salinger] knew he’d have to come forward [to testify]. He knew he could lose, but he was willing to take that gamble and try to control his writings and his letters.

DAVID SHIELDS: Why was he willing to take such a gamble? According to several of Salinger’s ex-girlfriends we spoke with, one of Salinger’s primary motivations was to prevent the exposure of his many epistolary relationships with very young girls—his pursuit, over many decades, of girls as young as fourteen.

PHOEBE HOBAN: The irony was overwhelming: the most famously private writer had to testify in court in Manhattan and make his very private personal letters public by filing them at the Library of Congress. As a result of the litigation, Salinger not only testified but also had to register all seventy-nine disputed letters at the Copyright Office, where any person willing to pay $10 can peruse them.

It’s remarkable to have a window into Salinger’s life through his actual postcards and letters, which were written in his actual hand. It really is like reading one of his characters’ diaries or something like that—a way to have the most intimate possible contact with this impossibly reclusive person.

LILLIAN ROSS: That terrible ordeal they put him through. . . . I had to go to court with him and hold his hand. He was so upset. He would come over to my place and wait until we’d have to go and I’d go with him. Literally, sometimes I’d have to hold his hands he’d be shaking so badly. Afterwards I’d make him chicken soup at the end of the day. He was such a sensitive and fragile person, so vulnerable to the world. He was such a sweet man.

J. D. SALINGER (October 7, 1986):

Q [ROBERT CALLAGY, ATTORNEY FOR RANDOM HOUSE]: “At any time during the past 20 years have you written any fiction which has not been published?”

A [SALINGER]: “Yes.”

Q: “Could you describe for me what works of fiction you have written which have not been published?”

A: “It would be very difficult to .”

Q: “Have you written any full-length works of fiction during the past twenty years which have not been published?”

A: “Could you frame that a different way? What do you mean by full-length work? You mean ready for publication?”

Q: “As opposed to a short story or a fictional piece or a magazine submission.”

A: “It’s very difficult to answer. I don’t write that way. I just start writing fiction and see what happens to it.”

Q: “Maybe an easier way to approach this is, would you tell me what your literary efforts have been in the field of fiction within the last twenty years?”

A: “Could I tell you or would I tell you? . . . Just a work of fiction. That’s all. That’s the only description I can really give it. . . . It’s almost impossible to define. I work with characters, and as they develop, I just go on from there.”

ROBERT CALLAGY: My thought is that he was not the J. D. Salinger who had been the vibrant novelist back in the 1950s, but he was definitely angry or disturbed or upset about something. Something must have happened [long ago] because when I asked him about letters written around that time, I’d say, “What did you mean?” And he’d say, “The young boy meant . . .” I thought it was odd that he’d describe himself in the third person. In all of the depositions that I’ve done, no one has ever referred to himself in the third person.

DAVID SHIELDS: He was trying to tell himself that he was no longer that young boy.

IAN HAMILTON: There is an overexcited, wound-up tone to those letters. He obviously did see some terrible things [during the war], and in some way I think he may have cracked up.

MORDECAI RICHLER: The letters are also, as Mr. Salinger noted with hindsight in court, occasionally gauche or effusive. “It’s very difficult,” he said. “I wish . . . you could read letters you wrote forty-six years ago. It’s very painful reading.”

ROBERT CALLAGY: At one point there was a sad episode that occurred when during one of the breaks he asked me for a Manhattan telephone book. I got it and gave it to him. He was clearly having trouble finding the number he wanted, so I said, “Can I look up the number for you?” And he said, “I’m trying to find my son’s phone number. He lives over by the Roosevelt Hotel.” And then he said he couldn’t find the number in the book, so he was not going to be able to contact him, which I thought was very sad.

MARK HOWLAND: [My high school students and I] read the actual deposition, which was some forty pages long, complete with instructions to Salinger’s lawyer not to interrupt Hamilton’s lawyer [Callagy]. It’s about as close as we felt we were ever going to get to the man, to hearing his words, even though they were just transcribed on a paper. Just when things started to get interesting, when the lawyer started asking about what he was working on now, how often he wrote, did he plan to publish, we turned the bottom of the last page and—blank. There was nothing else. Don’t know what happened to whatever was left of the transcription, but it wasn’t there.

PETER DE VRIES: If there are gaps in your story, they’re gaps Salinger wants in the story.

JOHN WENKE: There’s a part of him that enjoys the power game that went on when the Ian Hamilton biography was making its way through the courts. He wanted to be able to assert ownership of the letters that somebody else owns. An actual recluse or mystic wouldn’t care.

JOHN DEAN: I thought how little Salinger really needed to do [to make his case], other than he had to appear [for the deposition]; he had no choice because otherwise he could have been defaulted out of the litigation. He had to establish that he still was writing, that he was confident in his ability to write, and especially, that he had some use he could make of these letters, not that he couldn’t have maybe made the same claim to pass them on to his estate. I think it was stronger in the eyes of the court if he could make the point: Indeed I am still writing actively, and what I’m writing is none of your business; however, in that context, these letters are of interest to me.

PHOEBE HOBAN: Salinger said, “You’re chiseling away at my property at the same time as you’re saying you’re not stealing it.”

JUDGE PIERRE N. LEVAL: It is my view that the defendants have made a sufficiently powerful showing to overcome plaintiff’s claims for an injunction. The reasons that support this finding are: Hamilton’s use of Salinger’s copyrighted material is minimal and insubstantial; it does not exploit or appropriate the literary value of Salinger’s letters for future publication. . . . The biographical purpose of Hamilton’s book and of the adopted passages are quite distinct from the interests protected by Salinger’s copyright. . . . Although [Salinger’s] desire for privacy is surely entitled to respect, as a legal matter it does not override a lawful undertaking to write about him using legally available resources.

JOHN DEAN: [Leval] ruled against Salinger, finding that Hamilton had made fair use of Salinger’s letters. This was a very good district judge. He was a very fair and objective judge, and you couldn’t ask for a better trial judge. Salinger’s legal team appealed the case to the U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals.

—

JUDGE JON O. NEWMAN: In July 1983 Hamilton had informed Salinger that he was undertaking a biography of Salinger to be published by Random House and sought the author’s cooperation. Salinger refused, informing Hamilton that he preferred not to have his biography written during his lifetime. Hamilton nevertheless proceeded and spent the next three years preparing a biography titled J. D. Salinger: A Writing Life. An important source of material was several unpublished letters Salinger wrote between 1939 and 1961. Most were written to Whit Burnett, Salinger’s friend, teacher, and editor at Story magazine, and Elizabeth Murray, Salinger’s friend. A few were written to Judge Learned Hand, Salinger’s friend and neighbor in New Hampshire, Hamish Hamilton and Roger Machell, Salinger’s British publishers, and other individuals, including Ernest Hemingway.

Ian Hamilton located most, if not all, of the letters in the libraries of Harvard, Princeton, and the University of Texas, to which they had been donated by the recipients or their representatives. Prior to examining the letters at the university libraries, Hamilton signed form agreements furnished by the libraries, restricting the use he could make of the letters without permission of the library and the owner of the literary property rights.

In response to Salinger’s objections, Hamilton and Random House revised the May [1987] galleys. In the current version of the biography (the “October galleys”), much of the material previously quoted from the Salinger letters has been replaced by close paraphrasing. Somewhat more than two hundred words remain quoted. Salinger has identified fifty-nine instances where the October galleys contain passages that either quote from or closely paraphrase portions of his unpublished letters. These passages draw upon forty-four of the copyrighted letters, twenty to Burnett, ten to Murray, nine to Hamish Hamilton, three to Judge Hand, one to Machell, and one to Hemingway.

A few examples should suffice. Salinger, complaining of an editor who has rejected one of his stories—though calling it “[c]ompetent handling”—writes [that it was] “like saying, She’s a beautiful girl, except for her face.” Hamilton paraphrases: “How would a girl feel if you told her she was stunning to look at but that facially there was something not quite right about her?”

Salinger writes, “I suspect that money is a far greater distraction for the artist than hunger.” Hamilton paraphrases, “Money, on the other hand, is a serious obstacle to creativity.”

Salinger, conveying the adulation of Parisians toward Americans at the liberation of Paris, writes that they would have said, “What a charming custom!” if “we had stood on top of the jeep and taken a leak.” Hamilton paraphrases, “. . . if the conquerors had chosen to urinate from the roofs of their vehicles.”

The breach of contract claim was based on the form agreements that Hamilton signed with Harvard, Princeton, and University of Texas libraries. Salinger alleged that he was a third-party beneficiary of those agreements.

As to the standard, we start, as did Judge Leval, by recognizing that what is relevant is the amount and substantiality of the copyrighted expression that has been used, not the factual content of the material in the copyrighted works. However, that protected expression has been “used” whether it has been quoted verbatim or only paraphrased.

The “ordinary” phrase may enjoy no protection as such, but its use in a sequence of expressive words does not cause the entire passage to lose protection. And though the “ordinary” phrase may be quoted without fear of infringement, a copier may not quote or paraphrase the sequence of creative expression that includes such a phrase.

In almost all of those instances where the quoted or paraphrased passages from Salinger’s letters contain an “ordinary” phrase, the passage as a whole displays a sufficient degree of creativity as to sequence of thoughts, choice of words, emphasis, and arrangement to satisfy the minimal threshold of required creativity. And in all of the instances where that minimum threshold is met, the Hamilton paraphrasing tracks the original so closely as to constitute infringement.

IAN HAMILTON: Public awareness of the “expressive content” of Salinger’s letters was instantly extended the day after this judgment was released. The New York Times felt itself free to quote substantially not from my paraphrases but from the Salinger originals that I had so painstakingly, and—it now seemed—needlessly attempted not to steal.

ARNOLD H. LUBASCH: A biography of J. D. Salinger was blocked yesterday by a Federal appeals court in Manhattan that said the book unfairly used Mr. Salinger’s unpublished letters.

Reversing a lower court decision, the appeals court ruled in favor of Mr. Salinger, who filed suit to prohibit the biography from using all material from the letters, which he wrote many years ago.

“The biography,” the appeals court said, “copies virtually all of the most interesting passages of the letters, including several highly expressive insights about writing and literary criticism.”

In a footnote, the appeals court’s decision cited a letter . . . [in which Salinger] criticized Wendell Willkie, the 1940 President candidate, saying, “He looks to me like a guy who makes his wife keep a scrapbook for him.”

The decision included another footnote referring to a 1943 letter in which “Salinger, distressed that Oona O’Neill, whom he had dated, had married Charlie Chaplin, expressed his disapproval of the marriage in this satirical invention of his imagination: ‘I can see them at home evenings. Chaplin squatting grey and nude, atop his chiffonier, swinging his thyroid around his head by his bamboo cane, like a dead rat. Oona in an aquamarine gown, applauding madly from the bathroom. . . . I’m facetious, but I’m sorry. Sorry for anyone with a profile as young and lovely as Oona’s.’ ”

ROBERT CALLAGY: If you take this opinion to an extreme, what it says is that you can’t quote anything that has not been published before, and if you attempt to paraphrase, you’re at serious peril. Copyright law was created to protect an author in a property right, not to permit an author to obliterate the past.

JOHN DEAN: To be reversed by the Court of Appeals was a little bit of a reach. In a sense, Salinger got lucky on this one.

LEILA HADLEY LUCE: I was appalled to hear that Hamilton couldn’t even abstract or write about Jerry’s letters to Oona. Psychologically, that makes sense because they talk about the litigiousness of the paranoid. I suppose that’s what Jerry is: he’s paranoid. He always thinks people are going to encroach on his privacy.

ELEANOR BLAU: The Supreme Court yesterday let stand a lower-court ruling blocking publication of an unauthorized biography of J. D. Salinger.

Without comment or dissent, the justices declined to act on the decision last January by the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in New York City that the biographer, Ian Hamilton, had unfairly used unpublished letters written by Mr. Salinger.

Random House, Inc., the publisher of J. D. Salinger: A Writing Life, said the company and Mr. Hamilton would decide in the next few weeks which of two steps to take.

PAUL ALEXANDER: In a sense Salinger had killed Hamilton’s book, period.

PHOEBE HOBAN: If, in fact, unpublished letters are copyrightable, then biographers and journalists are highly constrained. It was a precedent-setting case. . . . Ian Hamilton was not allowed to publish his original biography.

JOHN DEAN: For any of us who’ve ever wondered about Salinger’s reclusiveness, there were some answers that came as a result of his lawsuit. This is not something somebody does who is afraid of a little publicity, because there’s nothing private about a lawsuit. Which shows the adamancy with which he believes in his privacy and the extent to which he is willing to go, which was obviously a painful route for him.

To continue to protect that privacy, in a broader sense, there are some controls he could ask for in the court; he could ask the judge, who knew he was reclusive and very private, to keep this as private as possible. But the fact that it went as far as it did, went through the process the way it did, shows that he was determined to prevail in the case. A deposition is more fun to take than to give. I’ve been on both sides, and believe me—it’s easier to ask the questions than answer them. To do it for any length of time is always difficult.

When an author writes a book and becomes successful, in a sense he’s saying, “Look at what I’m writing.” He’s thrusting himself out there. But I have a tremendous empathy for those who would like to retain their privacy. It is very difficult to do once you become a public figure. Salinger’s effort to do so by stopping all public appearances is about as extreme as possible. Now is he a public figure? Yes, he is.

—

DAVID SHIELDS: In January 1987, at the same time Salinger was under siege on the legal front, not only was William Shawn eased out at the New Yorker, but the owner of the magazine, S. I. Newhouse, chose as his replacement Robert Gottlieb, the editor in chief of the book publisher Knopf, rather than Charles McGrath, the magazine’s deputy editor and presumed successor. Salinger signed a three-paragraph petition that 153 other writers, editors, cartoonists, and New Yorker staff members also signed, urging Gottlieb to turn down the position, to no avail. Salinger’s last and best defender, who had overruled the other editors’ unanimous rejection of “Zooey” and had served as Salinger’s only editor until 1965, was out. So too, in a sense, was Salinger.

—

PAUL ALEXANDER: In 1987 Salinger created an enormous amount of buzz throughout the entertainment business. While he was embroiled in the lawsuit with Ian Hamilton, Salinger fell in love with another television actress, Catherine Oxenberg, who was appearing on Dynasty. She was young, beautiful, and vivacious, and she and the show attracted a huge following. According to Ian Hamilton, Salinger fell in love with Oxenberg the moment he saw her on television. Salinger had an M.O. for television actresses. He would call them up on the phone and say, “I’m J. D. Salinger and I wrote The Catcher in the Rye.” Talk about a pickup line! According to Hamilton, Salinger traveled to the West Coast to pursue Oxenberg. Press reports at the time said Salinger showed up at the studio unannounced and had to be escorted away from the studio. When these newspaper reports appeared, Salinger had his attorneys find Oxenberg’s agent and threaten a lawsuit, but no lawsuit was ever filed.

JEAN MILLER: The trip to Hollywood to see Catherine Oxenberg—I just didn’t want that to be true, but I knew how he felt about child actresses. It was just acting, so it was just as phony as anything else. It’s just as phony as a rock musician playing the same thing over and over again and getting the audience all riled up, and then stalking off the stage filled with ego.

DAVID SHIELDS: He wants to be a pure dharma being, but he falls head over heels for Catherine Oxenberg. Nearly every Salinger story traces the same circular movement: a character wants to escape the world, wants to graduate beyond desire and ego and other people, but by the end, the protagonist always comes back to the ordinary human drudge, to just living. Salinger’s life is a failed Salinger novel: he never truly re-embraces existence.

—

PHOEBE HOBAN: Ian Hamilton took a postmodern gambit and wrote a really crummy book about his search for Salinger and how he wasn’t allowed to write about Salinger.

MYLES WEBER: Hamilton asserted that Salinger became more famous by trying not to be famous; that he sold more books by not publishing any more books; that, in fact, it was his deliberate design.

MORDECAI RICHLER: Mr. Hamilton’s biography is tainted by a nastiness born of frustration, perhaps, but hardly excused by it. Mr. Salinger is never given the benefit of the doubt. He is described as a “callow self-advancer.” Aged twenty-two, we are told, “the Salinger we were on the track of was surely getting less and less lovably Holden-ish each day. So far, our eavesdropping had yielded almost nothing in the way of human frailty and warmth.” This vengeful book is also marred by Mr. Hamilton’s coy, tiresome device of splitting himself in two, as it were, referring to Mr. Salinger’s biographer in the third person.

—

DAVID REMNICK: In the spring of 1988, the editors of the New York Post sent a pair of photographers to New Hampshire with instructions to find J. D. Salinger and take his picture. If the phrase “take his picture” had any sense of violence or, at least, violation left in it at all, if it still retained the undertone of certain people who are convinced that a photographer threatens them with the theft of their souls, then it applied here. There is no mystery why the Post pursued its prey. . . . His withdrawal became for journalists a story demanding resolution, intervention, and exposure. Inevitably the Post got its man. The paper ran a photograph on the cover of a gaunt sixty-nine-year-old man recoiling, as if anticipating catastrophe. In that instant, the look in Salinger’s eyes was one of such terror that it is a wonder he survived it.

PAUL ALEXANDER: One day in April 1988—under the banner headline “GOTCHA CATCHER!”—the New York Post ran a full-page photograph of Salinger on its front cover. Obviously agitated in the picture, Salinger has one fist pulled back as if he is about to punch the camera. Paul Adao and Steve Connelly, both freelance paparazzi, had gone to New Hampshire, as had become the custom of so many fans and journalists through the years, and stalked Salinger for several days until they saw him coming out of the post office in Windsor. Clicking away, they photographed him as he walked up and spoke to them. “Listen,” he said sternly, “I don’t want to be interviewed. I don’t want any part of this.”

MYLES WEBER: An editor of the New York Post defended the work of his journalists by saying that, in fact, it was Salinger who was interfering with his journalists doing their job.

PAUL ALEXANDER: [Adao and Connelly] left, but three days later they returned and talked to people about Salinger again until they spotted him leaving the Purity Supreme supermarket in West Lebanon, New Hampshire.

Adao blocked Salinger’s car into its parking space, and after Connelly got out of their car, both of them began taking pictures of him. Furious, Salinger came at them, smashing his grocery cart into Connelly and hitting Adao, still in the car’s driver’s seat, with his fist. It was one of the times Salinger was drawing his fist back to swing at Adao that the photographer caught the gesture on film. Soon, giving up, Salinger covered his face with his hands and tried to open the door to his jeep, but the photographers kept snapping shots. Several shoppers stopped to gather around what had turned into a minor mêlée. “What are you doing to him?” one finally shouted out at the photographers. “He’s a convicted murderer!” Adao yelled back, a comment Adao later said he regretted. Finally, Salinger got into his jeep and, when Adao saw that Salinger was about to back into his car, he moved the car and Salinger drove away.

DAVID SHIELDS: Margaret says, “He still drives his Jeep like a nutcase, or a sane person being shelled, same regulation haircut, only gray now.”

After the picture appeared on the front page of the Post, a controversy ensued, with many readers disapproving of the way the paparazzi had stalked Salinger. Later, Don DeLillo said that photograph inspired him to write Mao II.

DON DeLILLO: The withheld work of art is the only eloquence that’s left.

—

JOHN DEAN: Clearly Salinger has not withdrawn from society. He is very aware of what’s happening as it is related to him. He’s probably got counsel keeping an eye on things and alerting him to misuses of his name.

DAVID SHIELDS: While he hadn’t fully withdrawn from society, he was clearly retreating. In 1990, Dorothy Olding, Salinger’s agent for fifty years, had a stroke. Her assistant, Phyllis Westberg, became his agent. Two years later, his editor, champion, and friend William Shawn died.

—

WILLIAM H. HONAN: Mr. Salinger’s modest house, surrounded by three plain garage-like structures, including the author’s writing studio, is positioned for privacy. To reach it, one crosses an old covered bridge high above a roaring brook and grinds for several miles up a steeply winding, hard-packed dirt road. The last 100 yards are an extremely steep grade, and the Salinger house, nearly invisible from the road, seems almost an eagle’s nest with a panoramic view of Mount Ascutney across the Connecticut River in Vermont. An immense white satellite dish behind the house suggests that Mr. Salinger is still in touch with the outside world, at least through television.

DAVID SHIELDS: In Cornish, Salinger surrounded himself with the dense, tall evergreens, the cold, dark winters, and the isolating terrain of Hürtgen, but now from a commanding position: he could easily detect approaching dangers—not artillery, of course, just literary tourists who wanted to invade his hilltop perch. He needs life to feel difficult.

LILLIAN ROSS: He liked living in New Hampshire, but he often found fun and relief by coming down to New York to have supper with me and Bill Shawn. In a note he sent after the three of us got together for the last time, he wrote, “It will set me up for months. I was at peace.”

—

SHANE SALERNO: Paul Fitzgerald was one of the “Four Musketeers” who served alongside Salinger during the war in the counterintelligence section of the 4th Division. From D-Day to Kaufering IV, Salinger and Fitzgerald were always together. The two men maintained a strong and warm relationship until Salinger’s death in 2010, writing each other frequently. The excerpts from Salinger’s letters to Fitzgerald that appear throughout this book have never been published before.

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from letter to Paul Fitzgerald (July 27, 1990):

I’m impressed, mightily, at the easy way you reel off the names of just about the whole CIC detachment people, victims, whatever it was we were. . . . Am very glad you’re well and happy, Paul. Stay that way. It takes some doing, at times, but do it anyway.

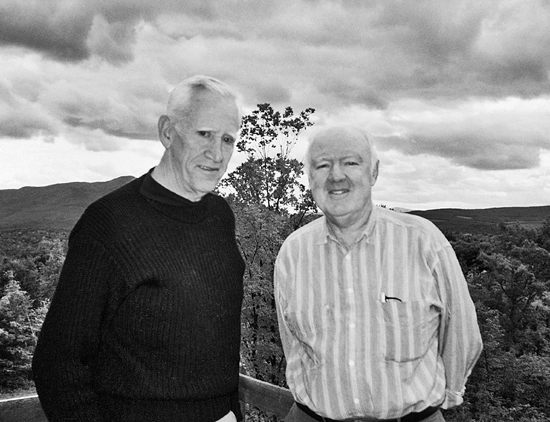

SHANE SALERNO: In September 1991, on a cross-country car trip, Fitzgerald surprised Salinger at his home in Cornish, New Hampshire.

PAUL FITZGERALD, diary entry, September 26, 1991:

Windsor, Vermont/Cornish, New Hampshire: Just across the Delaware River is a town called Cornish. The directions proved correct. Way on top of a wooded rolling hill sat Salinger’s abode. When he came to the door he looked inquisitive. Looking into the face of a baldheaded person changed by 46 years. I recognize him, tho he appeared much less vital—the eyes mellowed by age and serenity in the paradise. He was emotionally warm and welcoming. Entertaining his son and daughter-in-law. Invited in. They were having dinner.

Salinger and Paul Fitzgerald in Cornish, September 26, 1991.

PAUL FITZGERALD, diary entry, September 27, 1991:

Called on Salinger “way up the hill” at 3:15. Talked about old times. He’s a very warm person. Denise [Fitzgerald’s wife] liked him very much. His view is magnificent. He has 300 acres up here. Took off for parts unknown at 5.

—

ASSOCIATED PRESS: J. D. Salinger’s home was heavily damaged in a fire early today. No one was injured. Mr. Salinger’s wife, Colleen O’Neill, reported the blaze, Fire Chief Mike Monette said. He would not say if the reclusive writer was home at the time. The cause of the fire and damage estimates have not been determined.

DAVID SHIELDS: This was the first time—in 1992—that the public learned of Salinger’s third wife, forty years his junior. Colleen, a nursing student who worked as an au pair for someone else and married in the early 1980s, met Salinger, corresponded with him, and left her husband for the author.

PAUL ALEXANDER: Colleen directed the annual Cornish town fair.

BURNACE FITCH JOHNSON: Jerry used to come and walk around the fairgrounds with her. Colleen would have to repeat things to him when people spoke to him, because he’s quite deaf.

WILLIAM H. HONAN: Not even a fire that consumed at least half his home on Tuesday could smoke out the reclusive J. D. Salinger, author of the classic novel of adolescent rebellion, The Catcher in the Rye. Mr. Salinger is almost equally famous for having elevated privacy to an art form.

His fastidiously preserved seclusion was threatened on Tuesday when his third wife, Colleen, reported a fire in their home to the volunteer fire department. Within minutes, the blazing house was surrounded by fire trucks and emergency vehicles from Cornish, the New Hampshire towns of Plainfield, Meriden, and Claremont, and two small towns in Vermont, Windsor and West Windsor.

Mike Monette, Cornish’s fire chief, said the fire was brought under control in about an hour. No injuries were reported, he said, but “damage to the house was extensive.” Neither he nor anyone else was able to say whether any of the author’s unpublished manuscripts were destroyed.

On Thursday afternoon, Mr. Salinger, now 73 years old, cavorted around his property playing hide-and-seek with a reporter and a photographer who had come to learn how he was bearing up.

When first spied, Mr. Salinger, lanky and with snow-white hair, was outside his house talking to his wife and a local building contractor. As strangers approached, Mr. Salinger, like the fleet chipmunks that dash across his driveway, scurried into his charred retreat. The contractor barred the way of the pursuing reporter and pleaded, “You’ve got to understand, this is a man who is really serious about his privacy.”

Meanwhile, Mr. Salinger’s wife, who is considerably younger than her husband, strode vigorously toward a blue Mazda pickup truck in the driveway.

“I have things to do!” she announced, brushing aside all questions and glaring as she leaped into the vehicle and roared away. . . .

Mr. Salinger has kept aloof from his neighbors in Cornish as well as from prying journalists and the public. For example, Clara Perry, who was Mr. Salinger’s next-door neighbor for 20 years, ran a kindergarten attended by both of Mr. Salinger’s children, Matt, an actor, and Margaret Ann, now both grown. Mrs. Perry refers to him affectionately as Jerry but says that neither she nor her husband [was] ever invited into Mr. Salinger’s house. . . .

Mrs. Perry said that she and her six children had never cracked one of Mr. Salinger’s books because The Catcher in the Rye was banned at the Windsor public school they attended.

After the book became accepted, she said, the Windsor school used to send groups of students to visit with him. “But pretty soon he stopped that,” Mrs. Perry said. “It got to be too much for him.”

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from postcard to Paul Fitzgerald, December 1993:

Thanks, too, for your concern about the fire and the house, old friend. . . . The house has been pretty much re-built, and we’re now in it, at long last. . . . All kinds of D-Day commemorative stuff is slated to take place next June, or so I hear. In America, France, Germany. Speeches, no doubt. Lots of old guys standing around in Hawaiian shirts and little overseas caps. Still, there’ll be some long thoughts, here and there, surely. Myself, I think mostly of how young we all were.

SHARON STEEL: A fire ravaged Salinger’s home, and destroyed everything except a piece of his bedroom and, [as Salinger said,] “providentially,” his workroom, where he kept his papers and manuscripts.

—

JOYCE MAYNARD: There was this one woman overseas who had well over a hundred pages of letters from Salinger. He decided to come and visit her. He flew to London to meet her, and the excitement must have been extraordinary, I can imagine, because I know the excitement I felt when I pulled up to the Hanover Inn after just eight weeks of correspondence, and these two had been corresponding for much longer. She was a young woman, but it turned out she was not a particularly pretty woman. She was very tall and big-boned and kind of awkward.

DAVID SHIELDS: On this trip—to Edinburgh, actually—Salinger took his daughter with him. He said he said they were going to tour the Scottish settings for 39 Steps, the Hitchcock movie he especially loved.

PAUL ALEXANDER: Salinger had planned a meeting with a young pen pal amour at the Edinburgh airport. Upon meeting her there, Salinger expressed his embarrassment and guilt to Margaret. The young girl had simply turned out to be ugly.

JOYCE MAYNARD: Salinger evidently saw her and left. He told her he would see her again, and he asked her to send back the letters so that he could keep them for her when she came over to visit him. She mailed all of the letters back to Salinger and never heard from him again.

MARGARET SALINGER: His search for landsmen led him increasingly to relations in two dimensions: with his fictional Glass family, or with living “pen pals” he met in letters, which lasted until meeting in person when the three-dimensional, flesh-and-blood presence of them would, with the inevitability of watching a classic tragedy unfold, invariably sow the seeds of the relationship’s undoing.

JOYCE MAYNARD: There was another story about Jerry, and this one I heard not from the woman herself, because I don’t think that she was in a state to report it, but somebody else told me, a man who knew Jerry in town. Jerry corresponded with a young woman and had invited her to come and see him. She had actually moved to the town of Hanover to be near him, and she had come to see him, but he had very swiftly tired of her.

Jerry told a neighbor that he didn’t know how to get rid of the woman; she kept coming round and he reported her to the police, filing a complaint against her. I’m not going to ascribe total blame for this next event to Salinger, but I do understand the power of his dismissals and how crushing it could be. The woman had a total breakdown and was hospitalized in Concord, New Hampshire.

MICHAEL SILVERBLATT: Salinger’s books are in some crazy sense love letters to people he’d be reluctant to meet. In particular, they’re love letters to the lost—all versions of the fat lady who’s so normal she loves to laugh at the television set, and you’re doing it for the fat lady; he’s doing it for his fat lady readers.

—

JOYCE MAYNARD: I had a good friend named Joe, who was a Vietnam vet—100 percent disability for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. We were sitting in my kitchen one day, the year that Audrey [Maynard’s daughter] turned eighteen, and I was talking to him about the strange and unexplainable anxiety I was feeling about her going away from home. I’d always been a pretty relaxed and comfortable parent. He listened to me speak for a while and finally said, “So tell me, Joyce, what happened to you when you were eighteen?” I’d never mentioned Jerry Salinger to him, but I knew right away what the answer to that question was.

Joe suffered a Post-traumatic Stress Disorder breakdown when his oldest son reached the age Joe was when he went off to Vietnam. I remember waiting until my children went off to their father’s house that weekend; by this time, I was divorced for a number of years. I went to the back of my closet, where there was a shoebox, didn’t even know right away where that box was. I hadn’t looked at the letters from Jerry Salinger in twenty-some years.

I took them out, laid them out on my bed, and began to read them. They were letters I’d known very well. I could have recited some of them, I’d read them so carefully when I was young. I was reading them now as a forty-three-year-old woman, and the voice that moved me and melted my heart when I was eighteen struck me in a very different way at forty-three.

As hard as I had worked as a writer, and as much work as I had been doing over those twenty years, a crucial piece that I hadn’t addressed made it almost impossible for me to be honest and authentic about anything else.

In the winter of 1984 I was living in New Hampshire, married to my husband, Steve, and pregnant with our third child, our son, Willy. We had made a very rare trip to New York City to attend the publication party for a book in which I had an essay. It was a collection of essays by women writers who had published “Hers” columns in the New York Times, so there was a roomful of women writers. I was feeling a little unglamorous and unsophisticated and un–New Yorkish at that party, eight months pregnant, surrounded by slim, sophisticated New York writers. One came up to me and said—this happened periodically, somebody would refer to Salinger, and it was always an awkward moment when they did, because I didn’t speak of him and I never knew what to say—but this was a particularly awkward moment because I was at this party and couldn’t just walk away. She was a well-known writer, also in the collection. She came up to me and, apropos of nothing, said, “You know, I had an au pair girl who got letters from J. D. Salinger.”

I didn’t quite go into early labor, but it was that intense of a response. I felt my whole body shift. Up until that moment I knew that I had lost the love and high regard of Salinger, but I believed I occupied an absolute place in his heart and mind. I alone had experienced this, to me, intimate, sacred correspondence. Suddenly this woman I’d never met was telling me that her au pair had a packet of letters from Salinger. I was stunned, but I said nothing.

Quite a few years later I contacted her again and asked her to tell me more about the au pair girl and the letters. She explained the story: there had been a young woman named Colleen who had been a nursing student and then a nurse in Maryland. Colleen lived with her for a time, helping her take care of her children. At one point Colleen went up to Hanover to visit a boyfriend, got off a bus, and Salinger had given her a ride into town. They’d struck up a conversation and then had a correspondence. Colleen continued to see her boyfriend; she didn’t picture her correspondence with Salinger as a romantic situation. The writer went on to say that her au pair, Colleen, had married her boyfriend, and she had attended the wedding. She said, “I’ll send you a photograph from the wedding.” So a week or so passed and in an envelope came this photograph of a very pretty, smiling young woman wearing a taffeta dress, with her arm around a nice-looking young man.

MARK HOWLAND: In 1997 there was a lot of publicity about “Hapworth” coming out as a book. The word was that Salinger had to have absolute control over everything, including typeface and font size.

JONATHAN SCHWARTZ: There were rumors that Salinger was talking to a Virginia publisher about publishing “Hapworth.” Apparently they met several times.

IAN SHAPIRO: In 1988, Roger Lathbury, an English professor at George Mason University and owner of a small literary publishing outfit based in his house in Alexandria [Virginia], decided on a lark to write to J. D. Salinger, asking if he could publish “Hapworth 16, 1924,” Salinger’s last published work, which appeared as a story in the New Yorker in 1965 and never made it into book form. Amazingly, Salinger wrote back promptly, saying, essentially, “I’ll think about it.” Then, nothing. For eight years. Until July 26, 1996, when Lathbury, just having completed teaching his morning classes, picked up the phone in his home office.

ROGER LATHBURY: Here was the voice: “I would like to speak to Mr. Lathbury.” People don’t know how small the operation is here. His voice had a New York accent . . . and sounded like the recording of Walt Whitman that’s available. He identified who he was—I don’t remember if he said, “This is J. D. Salinger” or “This is Salinger”—and I said, “Well, um . . . I am delighted that you called.”

DAVID SHIELDS: Lathbury and Salinger arranged a meeting in Washington, D.C., at the cafeteria of the National Gallery of Art.

ROGER LATHBURY: I was a bit nervous. . . . His back was by the wall. He was waiting patiently. I shook hands with him and apologized for being late. . . . He was trying to make me feel at ease, but he was probably nervous, too.

IAN SHAPIRO: Salinger insisted on having no dust jacket, only a bare cover with cloth of great durability—buckram. They talked pica lengths, fonts, and space between lines. They were going to do a press run somewhere in the low thousands. No advertising whatsoever. But for how much? Lathbury remembers that Salinger did not ask for an advance and that any money to be made would come from sales.

DAVID SHIELDS: Lathbury filed a Library of Congress cataloging record for the book, a necessary first step toward publication. A very small magazine in Virginia heard that Lathbury had filed this information and called him to find out more.

ROGER LATHBURY: I foolishly gave an interview, but I thought nobody would see the article.

DAVID SHIELDS: A reporter for the Washington Post saw Lathbury’s interview and broke the news. Ego. Ego.

DAVID STREITFELD: J. D. Salinger, whose life has been one long campaign to erase himself from the public eye, is reversing himself somewhat at the age of 78. Next month will see the publication of Hapworth 16, 1924, the first new Salinger book in 34 years. Salinger is one of the most enduring and influential postwar American writers, and any New York publisher would have paid a bundle for the rights to the story, which appeared in the New Yorker in 1965. But in the literary coup of the decade, the book will be issued by Orchises Press, a small press in Alexandria run by George Mason University English professor Roger Lathbury.

MYLES WEBER: The book was listed for publication through Amazon and on the publishing company’s website.

SHANE SALERNO: In early February 1997, Hapworth 16, 1924 was—via prepublication orders—the #3 bestselling book on Amazon.

ROGER LATHBURY: This is a book meant for readers, not for collectors. Part of the reason for not revealing a press run is to discourage investing. I want people to read the story.

JONATHAN SCHWARTZ: When word got out [that the book was going to be published], Michiko Kakutani, the lead book critic at the New York Times, excoriated this story that had not been in print since 1965.

MICHIKO KAKUTANI: Seymour was the one who said that “all we do our whole lives is go from one little piece of Holy Ground to the next.” Seymour was supposed to be the one who saw more. It is something of a shock, then, to meet the Seymour presented in “Hapworth,” an obnoxious child given to angry outbursts. “No single day passes,” this Seymour writes, “that I do not listen to the heartless indifferences and stupidities passing from the [camp] counselors’ lips without secretly wishing I could improve matters quite substantially by bashing a few culprits over the head with an excellent shovel or stout club!” . . . In fact, with “Hapworth,” Mr. Salinger seems to be giving critics a send-up of what he contends they want. Accused of writing only youthful characters, he has given us a 7-year-old narrator who talks like a peevish old man. Accused of never addressing the question of sexual love, he has given us a young boy who speaks like a lewd adult. Accused of loving his characters too much, he has given us a hero who’s deeply distasteful. And accused of being too superficially charming, he has given us a nearly impenetrable narrative, filled with digressions, narcissistic asides and ridiculous shaggy-dog circumlocutions.

DAVID SHIELDS: According to Lathbury, Salinger broke off contact with him due to Lathbury’s unintentional betrayal of confidence, but isn’t it plausible to think that this was only Salinger’s cover story for his bruised feelings about Kakutani’s critique? Perhaps Salinger was testing the water for the possible publication of future Glass stories, and when the “newspaper of record” weighed in so heavily against, he retreated.

ROGER LATHBURY: My general feeling is anguish. I am very sorry. Those stories by Salinger provide release and delight for millions of people, and I could have helped to do that. I never reached back out. I thought about writing some letters [to Salinger], but it wouldn’t have done any good.

MYLES WEBER: It was reportedly withdrawn due to Salinger’s distaste for all that publicity, which really wasn’t much publicity at all by most publishers’ and writers’ standards. That’s one of the largest pieces of ammunition that scholars have to accuse Salinger of constructing an author persona, of having a deliberate agenda.

DAVID SHIELDS: In 2004 Lathbury revealed that he had lost the rights to publish “Hapworth” but refused to say how or why; in 2009 he showed up in a Washington Post profile, still refusing to talk about exactly what had happened.

JOHN WENKE: The aborted publication of “Hapworth 16, 1924” as a book is a perfect case study. The mystique really drives the obsession: people just want something else by Salinger.

There’s no aesthetic reason that I can think of for why Salinger would want “Hapworth” to be in print. The very fact that he’d had a deal with a small press in Virginia indicates that he was perfectly aware of the kinds of things likely to happen. I got phone calls from half a dozen newspapers about the publication of that book. I even got a call from [Australian Broadcasting Company] Radio in Sydney. I had to tell people that it’s not a new book; it’s something that he published in 1965 and anybody can walk to the library and pull down the issue of the New Yorker it’s in and read it. But he engineered that, and he did it very consciously, knowing there would be this stir.

RON ROSENBAUM: [“Hapworth” is] like the Dead Sea Scrolls of the Salinger cult. The real fascination is that somewhere buried in it you might find the key to Salinger’s mysterious silence ever since.

LESLIE EPSTEIN: “Hapworth” is a triumph; that’s the voice more than any other that reaches me. Why does that story upset people so much? There’s something about the purity of it, the integrity of it: the boldness of a boy looking us in the eye and telling us things that he makes us believe, even though he’s predicting his own death.

SHANE SALERNO: Having written two hundred pages of her memoir At Home in the World, Joyce Maynard went to Cornish on her forty-fourth birthday, November 5, drove to Salinger’s house, walked up to the front porch, and anxiously knocked on the door, believing this confrontation would provide closure.

DAVID SHIELDS: Writers know how vampiric other writers are. The only reason Maynard went to Cornish was to get a dramatic ending for her book.

JOYCE MAYNARD: I borrowed a truck and made my way to Cornish. I found to my surprise that I knew just how to get to Salinger’s house. I drove up the hill and parked the truck; the house looked surprisingly the same, although there was a satellite dish on the roof now. The garden had been cut back for winter. I walked up the steps to the door and thought, “This is the kind of moment when I should be really scared.”

But I wasn’t scared. I felt very calm. I knocked on the door. I heard a commotion in the kitchen and a woman called out to me, “What do you want?” I said to her, “I’ve come to see Jerry. Would you tell him Joyce Maynard’s here?” She turned and looked at me through the window and smiled. I recognized Colleen: the face of the au pair girl in the blue taffeta dress in the wedding picture sent to me years before, a little older now but still a lot younger than me. I stood there and waited. I didn’t want to have it said I ambushed him, that I had caught him unaware. Jerry was warned I was there and he had his own choice to make—to come to the door or not.

I waited a long time (I’m guessing ten minutes at least) but I knew that he would come to the door, and he did. The door opened and he stood there, wearing a bathrobe, very tall still, though a little more hunched over. He still had all his hair, but it was white. His face was much more lined. It was a face familiar to me, but the expression on that face was of great rage, something more than rage—hatred—more than I have ever experienced.

He shook his fist at me and said, “What are you doing here? Why didn’t you write me a letter?” I said, “Jerry, I’ve written you many letters; you’ve never answered them.” He asked again, “What are you doing here? Why have you come here?”

“I’ve come to ask you a question, Jerry. What was my purpose in your life?” When I asked him, his face, already filled with contempt, was transformed into this mask. “You don’t deserve an answer to that question,” he said. I said, “Yes, I believe I do.”

He exploded with a torrent of putrid language—the ugliest I’d ever heard—from this man who’d written some of the most beautiful words that had ever been written to me. He told me that I had led a shallow and meaningless existence, I was a worthless human being, and I’m actually grateful that he said those things to me because I knew those things weren’t true. Although he’d still written the same great books, was still the same wonderful, original, funny writer, he was no sage to me. He was no spiritual guide and the position that he occupied on the planet was the same as the rest of us: a flawed human being.

“I’ve heard you’re writing something,” he said. This was very like him: my book hadn’t even been written, yet word had leaked out in the press that I was going to be writing this memoir, and Jerry always watched what was going on and what was said about him in particular. He said it as if it were an obscene act to be writing a book. “Yes, I am writing a book; I’m a writer,” I told him. It’s odd. For all the years I’d been a writer, and all the books I’d written, I had never said “I’m a writer.” I always said “I write.”

I realized this was the breakthrough that allowed me to write my book: I had nothing to be ashamed of. Other people may say differently. I told the story that I had lived.

“The problem with you, Joyce,” he said, “is you love the world.”

DAVID SHIELDS: Salinger is expressing the core principle of Vedanta’s fourth stage: renunciation of the world. Writing, publishing, Joyce Maynard in all her ambition—they are the exact opposite.

JOYCE MAYNARD: When he said it, I felt as if he had just released me. Because to me that isn’t a problem at all. I said, “Yes, I do love the world and I have raised three children who love the world and I’m glad of that.” He replied, “I always knew this is what you’d amount to—nothing.” This was the man who had written me, who had told me to never forget that I was a real writer and to let nobody ever tell me differently. “And now you mean to exploit me.” I said to him—one of those rare moments when you actually do say the thing, you don’t just think of it later—I said, “Jerry, there may be somebody standing on this doorstep who exploited somebody else standing on this doorstep, but I leave it to you to determine which one is which.” I said goodbye. I am quite sure that is the last time in my life that I will ever see J. D. Salinger.

PAUL ALEXANDER: As she was walking away, Salinger shouted after her, “I don’t even know who you are!”

JOYCE MAYNARD: [I felt] different stages of distress from the moment of his initial rejection of me. I expected to be with him forever. I really did. I felt the reverberations of his disdain and contempt for years. After almost everything else was gone, I held on to this idea that I once was special and deeply loved by him. I had lived for his approval and it was a very painful thing to lose it and then to discover that I hadn’t in fact been this single and precious person. I had been one of a series of who knows how many.

DAVID SHIELDS: The damage inflicted feels intentional. It’s punishment on Salinger’s part—punishment for being alive.

JEAN MILLER: That poor girl—he was so casual and cold to her. She was very courageous in breaking the code that we all had, not verbally but emotionally, signed onto: don’t talk. I thought her parents were similar to mine. I also think, when you compare a picture of me and her picture on the back of her book, we look very much alike.

GORE VIDAL: Since Maynard was the victim, she has the right to complain first. She was the victim of an old man’s lust and whatever happened between them. Who knows? Who cares? I think the defense always has the right to come forward with their case first. So she did. So she did.

JOYCE MAYNARD: For twenty-five years, I did not write or speak of what happened. The [critical] attacks, not only on my book but on my character, were brutal, intensely personal, and relentless, and even now—several years later—hardly a week goes by in which someone or other doesn’t remark to me, “Oh, you’re the one who wrote the book about Salinger.” I’m never angry when they say that. Of course that was said in the press about the book. My response is: I didn’t write a book about J. D. Salinger. I wrote a book about myself, and J. D. Salinger chose to be a part of my life and I chose to no longer exclude that fact of my life.

I did, however, receive affirmation of the work I’d written. I received letters from women and men well acquainted with shame and secret-keeping in their own lives, thanking me for my willingness to speak openly of experiences they had supposed were theirs alone or simply too painful to speak of. . . . Not wholly surprising to me were the letters I received from three other women telling me they had engaged in correspondences with J. D. Salinger eerily like my own, one within weeks of his dismissal of me. I have no doubt these women’s stories were true. They quoted lines from Salinger’s letters to them nearly identical to ones in his letters to me, whose contents had never been made public. Like me, these women had been approached by Salinger when they were eighteen years old. Like me, they once believed him to be the wisest man, their soul mate, their destiny. Like me, they had eventually experienced his complete and devastating rejection. Also like me, they had maintained for years the belief that they were obligated to keep the secret out of fear of the very form of condemnation I was now receiving for having refused to do so. My book’s not really a story about J. D. Salinger; it’s a story about shame and a young girl giving over her power to a much more powerful older man, and that’s a rather universal story, or at least a common one.

—

JOYCE MAYNARD: Evidently it appeared to many of my critics that the sole significance of my life had been sleeping with a great man.

DAVID SHIELDS: It’s not as if Maynard isn’t highly exploitative in her own right, but it’s a bit of a daisy chain, because so much is at stake—the myth of the isolated male genius artist—and everyone is invested in it: newspapers, magazines, publishers, Salinger himself. The mystery surrounding the sphinx gets maintained.

LARISSA MacFARQUHAR: In the 25 intervening years, Maynard bought a house, nearly had a nervous breakdown, lost her virginity to the soundtrack of Pippin, met Mary Tyler Moore and Muhammad Ali, was raped, got married, appeared on TV, had three children, emptied her breast milk into the Atlantic, planted a garden, went broke, had an abortion, clawed through a heap of garbage looking for a lost retainer, wrote three novels, watched her parents get divorced and die, got divorced herself, bought another house, got breast implants and took them out, took tennis lessons, sold most of her possessions and moved from New Hampshire to California. Over the years, Maynard has related many of these events in her syndicated newspaper column and in articles for women’s magazines.

ELIZABETH GLEICK: Flatly written, with detail piling upon detail like so much slag on a heap, Maynard’s memoir returns repeatedly to the idea of emotional and literary honesty. “Some day, Joyce, there will be a story you want to tell for no better reason than because it matters to you more than any other,” Salinger [once told] her. “You’ll simply write what’s real and true.” Maybe this is it. But where Salinger, or many a better writer, would have fictionalized his truths, opening up new universes for the reader, Maynard sheds no light on anything beyond the little spotlight she is standing in. She had a complicated childhood, a shattering love affair, a complicated adulthood. Join the club, kiddo, as Salinger himself might say.

CYNTHIA OZICK: What we have is two celebrities, one who was once upon a time a real writer of substance and an artist, and one who has never been an artist and has no real substance and has attached herself to the real artist in order to suck out his celebrity. It’s really such a Jamesian story, isn’t it?

JONATHAN YARDLEY: [At Home in the World is] smarmy, whiny, smirky, and, above all, almost indescribably stupid.

JOYCE MAYNARD: I wonder, why you are so quick to see exploitation in the actions of a woman—sought out at eighteen by a man thirty-five years her senior who promised to love her forever and asked her to forswear all else to come and live with him, who waited twenty-five years to write her story (HER story, I repeat. Not his). And yet you cannot see exploitation in the man who did this. I wonder what you would think of the story if it were your daughter. Would you still tell her to keep her mouth shut, out of respect for this man’s privacy?

JULIET WATERS: The intensity of the literary catfight sparked by Maynard’s At Home in the World is a bit disturbing. There was a lacerating review in the New Yorker that casually dismissed the emotional and sexual abuse Maynard suffered at the hands of her parents with the claim that this paled compared to the sin of having “led their daughter to believe that she, and everything she says or writes, is of supreme interest.”

MICHIKO KAKUTANI: Although many readers will doubtless find the Salinger chapters the most compelling—and unsettling—part of this book, “At Home in the World” is not a sleazy tell-all memoir about the author’s affair with a famous (and famously reclusive) man. It’s actually an earnest, if at times self-serving, autobiography that, in the course of tracing the author’s coming of age, delineates her first serious love affair, one that happened to be with the author of “Catcher in the Rye.”

LISA SCHWARZBAUM: Defiant, taunting, score settling, and exhibitionistic as this memoir is, at least it isn’t as exasperatingly self-satisfied as most of Maynard’s other personal journalism; in its twisted way, and with a long, long way to go in the self-awareness department for the memoirist, it may be the most honest autobiographical work she’s done.

KATHA POLLITT: It’s easy to make fun of Joyce Maynard. As if her relentless self-marketing and theatricality weren’t enough, the very fact that she presents herself as vulnerable, a victim in recovery, leaves her open to mockery. In our heard-it-all-before sophistication, we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that while still very young Maynard was on the receiving end of quite a bit of damage from adults. If she doesn’t always seem to understand her own story—if she seems like a 44-year-old woman who is still 18—maybe that goes to show how deep the damage went.

JOYCE MAYNARD: Anybody who had a correspondence of any length with Salinger probably knows two things about him. One is how funny and lovable and tender and utterly winning he could be. The other is how cruel. If you’ve experienced the cruelty, if you’ve been burned by that flame, you might not be very quick to go anywhere near it again. I heard quite a few stories from women after I published At Home in the World.

DAVID SHIELDS: One of the most powerful contradictions in Salinger consists of how little contradiction this completely contradictory, even hypocritical, man can countenance in others.

JOYCE MAYNARD: Based on what was so often said about me for breaking my own silence, the fears of these women to speak of their experiences appear justified. Even now, it seems, there are many who would say it remains a woman’s obligation to protect the secrets of a man for the simple reason that he demands it. More than that, it appears to be a matter of some dispute whether a woman has the right to tell the truth about her life—and if she does, whether the story of a woman’s life is viewed as significant or valuable.

I was giving a speech one time, and the woman who introduced me said, “Well, she used to be J. D. Salinger’s girlfriend.” I thought, “God, is that all I’ve been?” I didn’t want to be reduced to that.

A MAN MAYNARD DATED: Fifteen minutes into our first date [in the 1990s], Joyce kept referring to this guy named Jerry. She was talking about “Jerry this” and “Jerry that.” It was as though they still knew each other. It took me a few minutes to figure out that the Jerry she was talking about was J. D. Salinger.

—

J. D. SALINGER, excerpt from card to Paul Fitzgerald, December 1998:

Paul, old friend, No real news, and little cheer this year, but winter, snow on the ground, is so reminiscent of places and Times half a century old. Not bad at all that we survived them. . . . A book I like very much, and you might, too Berlin Diaries, 1940–1945, by Maria Vassiltchikov.

—

CATHLEEN McGUIGAN: Now, 27 years later, “Miss Maynard,” as he addressed her, is putting up that letter and 13 others for public auction next month at Sotheby’s in New York. . . . So rare are Salinger letters—and so notorious is their romance—that Sotheby’s estimates they will sell (as a group) for $60,000 to $80,000. . . .

Selling the letters, she says, is practical. “I’m a single mother of three children,” explains Maynard, 45, from her home in California. “I don’t feel any embarrassment at the financial reality of being a writer who’s not J. D. Salinger.”. . .

The new letters are hardly lurid or full of secrets—Maynard already described them in her memoir. Yet actually reading them . . . is a treat. . . . “[There are] wonderful things in those letters,” notes Maynard. “But there’s also an enormous amount of bitterness and disdain for the world.” . . .

Salinger is seductive in his praise of Maynard’s writing, her mind, his suggestion that they are soul mates. He signs off, “Love, Jerry.” What bright but naive 18-year-old with literary ambitions wouldn’t fall for this from a brilliant, sensitive, famous writer?

Writer Joyce Carol Oates says she has “mixed feelings” about the sale of the letters but notes that the press has treated Salinger “like he’s sacrosanct. . . . How old was he then? He must have known at the time that this was reckless behavior.” And Maynard apparently wasn’t the only woman to whom Salinger, now 80 and remarried, wrote. Oates says she has a close woman friend who had an affair with Salinger and has letters from him. Maynard herself has heard of others. “It was a painful discovery that there had been other girls,” she says. “But it began to set me free from the worship of this man who had presided over my life for so long.” When his letters go on the block in June, Maynard will be there to hear the gavel fall.

JOYCE CAROL OATES: What of the letter-writer’s complicity in his “betrayal”? No one forced J. D. Salinger in the spring of 1972 to initiate an epistolary relationship with an 18-year-old college freshman; no one forced the 53-year-old writer, at the height of his perhaps sufflated fame, to seduce her through words, and to invite her to live with him in rural New Hampshire.

Though Joyce Maynard has been the object of much incensed, self-righteous criticism, primarily from admirers of the reclusive Salinger, her decision to sell his letters is her own business, like her decision to write about her own life. Why is one “life” more sacrosanct than another? In fact, we might be sympathetic to J. D. Salinger’s increasingly futile efforts to safeguard his precious privacy, as we might be sympathetic to anyone’s efforts, but that he happens to be a writer with a reputation is irrelevant.

JOHN DEAN: When Maynard decided she was going to sell Salinger’s letters, she was smart enough, I’m sure, to know, because of Salinger’s lawsuit against Random House, she could not sell the content of the letters: all she could do is sell her right to own the physical letters themselves. She turned them over to Sotheby’s to sell; all they sold was the physical paper.

MAUREEN DOWD: I went to Sotheby’s . . . to have a gander at the notorious letters. The exercise was fascinating and a little creepy. The 53-year-old author kept warning his 18-year-old friend about the ways that celebrity and conspicuousness can warp talent. Now those warnings against exploitation are being exploited. His counsel for privacy and subtlety are being publicly and unsubtly sold to the highest bidder.

PHOEBE HOBAN: The only reason those [letters] are not in some private person’s hands now, but back in Salinger’s possession, is that Peter Norton, the software developer, thought it was such a terrible act of disloyalty that he bought the letters and returned them to Salinger. I thought it was one of the noble acts of the twentieth century.

JOHN DEAN: The buyer of the letters, Mr. Norton, returned them to Salinger: all he was doing was returning the physical possession of the letters because Salinger already owned the content of the letters. This kept them out of public circulation.

MARC PEYSER: Peter Norton, a software millionaire and art collector, forked over $156,000 last week to buy Salinger’s letters from navel-gazing writer Joyce Maynard, who lived with the reclusive author in the 1970s. Norton doesn’t criticize Maynard; he just wants to keep the letters from ruining Salinger’s privacy.

PETER NORTON: My intention is to do whatever he wants done with them. He may want them returned. He may want me to destroy them. He may not care at all.

—

DAVID SHIELDS: Shortly after Salinger survived the attack from Maynard, he needed to gear up to do battle with another young woman about the same age as Maynard—his daughter, Margaret.

DOREEN CARVAJAL: The daughter of the obsessively private author J. D. Salinger is preparing to publish a memoir of her childhood and relationship with her father. The book by Margaret (Peggy) Salinger, 43, is tentatively titled “The Dream Catcher” and is scheduled to be published by Simon & Schuster’s Pocket Books in the fall of 2000. Ms. Salinger received an advance from Pocket Books of more than $250,000.