chapter 10

three tactical challenges

COMPLICATIONS AND HOW TO HANDLE THEM

You now know everything you need to get started with reframing. There’s more to learn if you want to achieve full mastery of the method, but much of that learning will come from practical experience as you apply it to your own problems and those of your clients, colleagues, and friends.

I still have more to offer, though. As you work on real-world problems, you’ll eventually run into what I think of as complications. These are the various practical obstacles to reframing, such as when other people resist the process, or if you have no clue what’s causing a given problem.

That’s the topic of this part of the book. In the next chapter, I’ll share advice on how to overcome resistance to reframing. In this chapter, we’ll take a look at how to handle three common tactical challenges:

- Choosing which frame to focus on (when you end up with too many framings)

- Identifying unknown causes of a problem (when you don’t have any idea what’s going on)

- Overcoming silo thinking (when people resist outside involvement)

This part of the book is meant as a go-to resource, so if you are eager to get started, just bookmark it and skip ahead to the final chapter, “A Word in Parting.”

1. CHOOSING WHICH FRAME TO FOCUS ON

When trying reframing for the first time, some people will likely voice a specific frustration: When I started this, I had one problem. Now I have ten problems. Thanks, reframing method, veeery helpful.*

Feeling frustrated isn’t necessarily a bad thing; it’s a normal part of the process. At first it might be annoying that you no longer have a “simple” view of the problem—but generally, that’s balanced out by the benefits of not solving the wrong problem.

Still, there is a very practical question to deal with: If you come up with multiple different framings of the problem, how do you decide which frames to explore and which to ignore?

In some situations, with very important, do-or-die problems, it makes sense to go through a methodical analysis of every single framing, reality-testing them one by one. Typically, though, you’ll have neither the time nor the resources—nor the patience—to do that. Instead, you’ll have to select one or two framings to focus on, at least until the next iteration of the process. How, then, can you best do that?

While problems are too varied for a fixed formula to work consistently, I’ve found three rules of thumb that can help. As you review the framings, pay special attention to the ones that are:

- Surprising

- Simple

- Significant-if-true

Explore surprising framings

When you reframe a problem, you (or the people you help) will sometimes express surprise at a specific framing: Oh? I hadn’t thought about that angle. In my workshops, people have described it as an almost physical sensation—a visceral sense of relief upon finding a new perspective on their problem.

The sensation of surprise doesn’t ensure the framing in question will ultimately be viable. Still, such framings should usually be explored. The feeling of surprise arises exactly because the framing breaks with a mental model that the problem owner has been trapped in—increasing the chances that the new perspective will help.

Look for simple framings

In the popular imagination, breakthrough solutions are often associated with complex new technology. The location function on smartphones, for instance, relies on quantum mechanics, atomic clocks, and orbiting satellites to accurately pinpoint where you are. Given that, it can be tempting to think the best solutions come from esoteric, highly nuanced approaches to the problem.

In my experience, that’s rarely the case. In daily life, good solutions (and the corresponding problem framings) are fairly simple. Remember Lori Weise’s solution to the shelter-dog problem, for instance. That was just about keeping the dogs with their first family. The best solutions often have a ring of retrospective inevitability. Once identified, people react with, Of course! Why on earth didn’t we think of that earlier?

When you consider which reframings to pursue, you should generally gravitate toward the simpler ones. The medieval friar-philosopher William of Ockham is credited with the notion of “Occam’s razor,” which is a catchy way for scientists to say that when you face multiple possible explanations for a phenomenon, go with the one that’s most straightforward.*

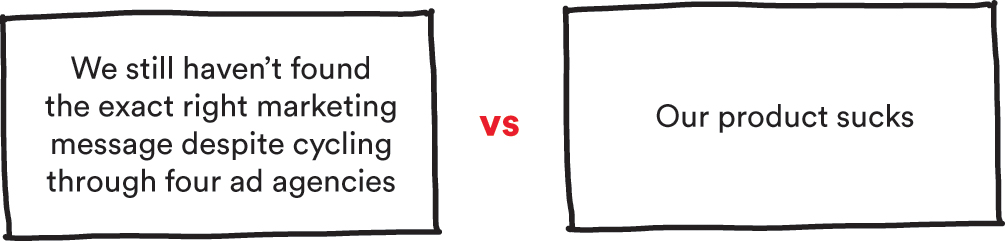

Translated to workplace problems, take the following two framings and consider which one Occam’s razor would point to: People aren’t buying our product because …

The emphasis on simplicity is a guideline, not an iron law. Some problems ultimately do require complex, multipronged solutions to be effectively resolved. But as Steve de Shazer wrote, in regard to his experience with therapy: “No matter how awful and how complex the situation, a small change in one person’s behavior can make profound and far-reaching differences in the behavior of all persons involved.”*

Look for significant-if-true framings

Finally, it can sometimes make sense to test framings that you do not believe in.

Reframing, by nature, is about challenging your assumptions and beliefs about a problem. Sometimes, simply hearing a new, unexpected perspective can be enough to make you reconsider your previously held beliefs. But more often, when you come across a truly powerful framing, your gut reaction—or what we more nobly call our intuition—may well be negative. And when it comes to reframing, you have to be careful about trusting your intuition.

This may strike you as odd. After all, much of the personal advice industry lives on one message: trust your gut. We tend to trust our immediate feelings about something without really questioning where those feelings come from. But your “gut” is really just your brain’s subconscious summary of what has worked in the past. And here’s the thing: creativity often involves transcending your past experience, breaking with at least one or two of your assumptions. Your intuition is built from your past. For exactly that reason, it’s not always a good guide to your future.

What that means is, even if a framing goes against your gut, you shouldn’t dismiss it before asking: If it were true, would this framing have a big impact? Such framings can be worth exploring even if you think their odds of being right are minimal—provided the testing of that frame doesn’t require excessive resources.*

The Bolsa Familia program. One example comes from Brazilian politician and former president Lula da Silva. Most recently, Lula gained a level of infamy as he was found guilty of corruption. Before that, however, he attracted positive international attention by creating a successful initiative for alleviating poverty, the Bolsa Familia program.

As described in Jonathan Tepperman’s book The Fix, the program shifted from trying to provide services to poor families to just giving the poor money, allowing the families to spend it on the goods and services they wanted.

Despite being simpler and cheaper—one study estimated it to be 30 percent less costly than providing traditional services—the idea of giving people money had been firmly rejected by local and international experts, most of whom were convinced that poor people would waste the money on vices and other frivolous things. Lula, however, had grown up poor, and knew that those prejudices were inaccurate: poor people—especially mothers—generally will spend money wisely. As a result of the Bolsa Familia program and other initiatives, Brazil’s extreme poverty rate was cut in half, lifting thirty-six million people out of the most severe category of poverty and providing a bright spot for other nations’ efforts to tackle income inequality.

The question that strikes me is, could one of those former policy makers have come up with the idea, despite their instincts? Using this test, they may have said, “I don’t believe poor people can handle money responsibly. But I recognize that there’s a small chance I am wrong about that assumption—and if I am, we could make a huge difference, because money transfers would be vastly more efficient than providing goods and services. With that in mind, why don’t we set up a small experiment to test whether I’m right?”

Try to explore more than one framing

No matter which selection strategy you use, note that the point of this selection process isn’t to arrive at one final framing. Some of the teams I’ve worked with picked a primary frame to explore, and then designated some of the team members to explore second or third frames as well. Unless you have to commit to an immediate solution, parallel explorations can be worth the effort. Failed avenues of inquiry will sometimes prove helpful later, even if it’s just to tell a stakeholder, “We tested that angle, and it didn’t work.”

2. IDENTIFYING UNKNOWN CAUSES OF A PROBLEM

Imagine you face a problem, only your initial analysis (including your attempts to reframe it) didn’t yield a clue as to what’s causing it. What then?

We’ve already covered one method you can try, namely the idea of broadcasting the problem, which you read about in chapter 6, “Examine Bright Spots.” Here, I’ll share two other methods you can use to uncover the hidden causes of a problem: discovery-oriented conversations and learning experiments.

Discovery-oriented conversations

Sometimes, a simple conversation with the right person can be enough—provided you pay attention to what the person is really saying.

A few years ago, two entrepreneurs by the names of Mark Ramadan and Scott Norton launched Sir Kensington’s, a line of condiments including ketchup, mustard, and mayonnaise.* The idea was to create a tastier, healthier, all-natural alternative to the existing offerings.

Two years in, their products were selling well, and demand was growing. But for some reason, the sales of their ketchup lagged. The problem was not about the taste: customers said they loved it. But they were buying less of it than their enthusiasm suggested they would.

Mark and Scott thought it might be related to the shape of the bottle. When they launched the company, they had chosen to use square glass jars for all of their products to create a high-end brand: instead of a plastic squeeze bottle, people got a stout glass jar reminiscent of fancy mustards. The strategy served them well overall, judging by the sales of their other products. But it wasn’t working with their ketchup.

Mark and Scott debated whether they should switch to a more traditional bottle shape, just for the ketchup. It was a big decision. Changing would affect every part of their supply chain and create complexity in operations. If they got it wrong, it would take a year to reverse the decision. Mark and Scott wanted to make sure they were doing the right thing—and that meant figuring out what was really going on with the ketchup sales.

Pause and consider what a big company might have done here. The head of marketing might have decided to run a survey, or bring together some focus groups. Or perhaps, the company would have forked over a couple of hundred thousand dollars to run an in-depth ethnographic study, having professional researchers follow people on their shopping trips and in their homes.*

These methods would likely yield useful insights, and many big companies have used them to create growth. Being part of a startup, though, Mark and Scott didn’t have the option of doing any of those things—so instead, they just started talking to people they knew: customers, investors, and friends who used their products. The clue came when one of their investors told them: “I tried the sample you sent me, and I really love it. I still have it in my fridge.”

That remark made Mark and Scott pause. The investor had received the bottle months earlier—so if he loved it, why did he still have the original bottle in the fridge? Why hadn’t he used it up by now?

The answer turned out to hinge on a small detail about how most people store ketchup. Mark found that people tend to stock mustard and mayo on the main shelves, which leaves those condiments in plain sight the next time people open the fridge. Ketchup tends to get stuck in the shelves on the door. If the shelf’s guardrail is transparent, that’s not a problem. But in fridges with nontransparent guardrails, Sir Kensington’s square ketchup bottle disappeared from view. As Mark put it, “If you can’t see the bottle, you don’t take it out as often. Out of sight, out of mind.”

The discovery of the fridge problem gave Mark and Scott the confidence to change to a taller bottle. Once it hit the market, sales velocity increased 50 percent.

As the story shows, you’ll sometimes find important clues in simple conversations—provided you pay attention to what’s being said. When their investor casually mentioned that he still had the original bottle, other people might not have caught the significance of the remark. Mark and Scott, however, were attuned to it: they were listening for clues to the problem, which yielded the key piece of information.

What does it take to do this? The topic of listening and questioning has been widely explored within management science and elsewhere. A full summary is beyond the scope of this book, but I’ve listed three pieces of advice here on which there’s widespread agreement.†

Step into a learning mindset (aka, shut up and listen). The management scholar Edgar Schein has pointed out in his work on “humble inquiry” that we too often start conversations with the aim of telling.* A key step happens before you enter the conversation, as you remind yourself to approach the other person with an intent to listen and learn.

As an aside, when reframing problems in a group, try to notice your own talking-to-listening ratio. Given five minutes to discuss their own problem, some people spend four of the five minutes talking, leaving little room for input. If you tend to talk a lot as well, you might consider experimenting with listening more.

Create a safe space. As shown by Amy Edmondson’s work on psychological safety, learning conversations are less effective if people fear recrimination or otherwise feel they can’t speak freely.* Find ways to de-risk the conversation—or consider having a third party do the interviews.

Seek out discomfort. As we discussed in chapter 7, “Look in the Mirror,” to get to the useful insights, you must be prepared to discover potentially painful truths about yourself. As MIT professor Hal Gregersen and his colleagues have documented, many leading business people credit their success in part to their ability to put themselves in uncomfortable situations.* (This also applies to your selection of who you speak to: Do you seek feedback only from people who will tell you pleasing things?)

Run a learning experiment

If conversations don’t yield any clues to the nature of the problem, another strategy might involve running a small learning experiment. A learning experiment, simply put, is a deliberate attempt to do things differently from how you normally do them, in order to shake things up and learn something new.

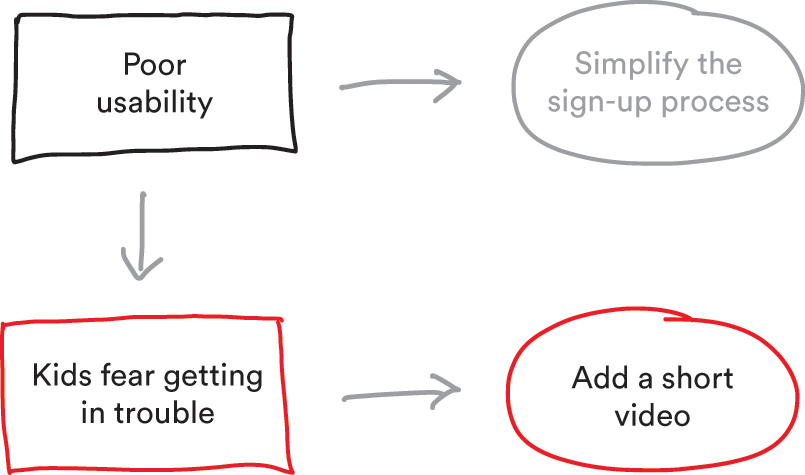

Jeremiah “Miah” Zinn did this when he worked at the popular children’s-entertainment television channel Nickelodeon—home to immortal cultural figurehead SpongeBob SquarePants.* Miah ran the product development team, which had just come up with an exciting new app aimed at kids aged seven to twelve. The team knew from testing that kids loved the content—and indeed lots of kids downloaded the app. But then, a problem appeared. As Miah put it: “To use the app, you had to go through a one-time sign-up process—and as part of that, you had to log into the household’s cable TV service. At that point, almost every single kid dropped out of the process.”

There was no way around the sign-up requirement, so Miah’s team had to figure out how to guide kids through the process and increase the sign-up rate. And they had to do it fast: every day without a solution cost them users. Under pressure, they went straight to a method they knew exactly how to wield: usability testing.

“We set up hundreds of A/B tests,” Miah said, “trying different sign-up flows and testing new ways of wording the instructions. Let’s try twelve-year-olds in the Midwest—do they react better if we switch the steps around?”

There were good reasons for the team’s reliance on A/B testing. Since its humble beginnings in the late 1980s, with the publication of Donald A. Norman’s classic book The Design of Everyday Things marking the breakout moment, usability testing has become a common and powerful tool for tech companies. One big tech company famously tested more than forty shades of blue to find the exact right color for its search page.

But as Miah said, “The problem was, none of our tests moved the needle. Even the best ones only nudged the sign-up rate a few percentage points at most.”

To break out of their rut, Miah decided to try something new:

We had focused on gathering lots of data, looking at big groups. How many percent swiped here or tapped there? And that had gotten us nowhere. So I had a thought: Instead of studying lots of kids from afar, why don’t we invite a couple of them into our office, parents in tow, and sit next to them and see what happens as they try to log in?

It was a pivotal decision. As Miah’s team interacted with the kids, it became clear the problem wasn’t about usability. The kids had no problem understanding the instructions or navigating the log-on process. (These days, most ten-year-olds can crack a safe in five minutes flat.) The problem was about their emotions: the request for the family’s cable-TV password made the kids fear getting in trouble. To a ten-year-old, a password request signals forbidden territory.

Miah’s team immediately abandoned their efforts to fix the sign-up process. Instead, they produced a short video explaining to kids that it was perfectly okay to ask their parents for the password. No worries, young grasshopper! You won’t get in trouble by asking! The result: an immediate tenfold increase in the sign-up rate for the app. From that day onward, Miah made sure that their product-development processes also included some in-person user testing in addition to their A/B testing.

Tests versus learning experiments. Miah’s story shows the difference between testing and experimenting. When Miah’s team first attacked the problem, they didn’t stick only to analysis. They tested hundreds of different permutations of sign-up flows on real customers, in real time. If you had walked into their office and proclaimed, “Folks, we need to do some experiments to figure out the answer,” they would have looked at you weirdly: That’s what we’re doing!

The issue was that their tests were focused on the wrong problem. The team found a way to move forward only with Miah’s decision to try something different. Instead of continuing to tweak the usability testing—What if we make the button sliiiightly more blue?—Miah stepped back and asked, Is there something else we can do to learn more about the problem? Something we haven’t tried before?

That is the essence of learning experiments: When you are stuck, instead of persisting with your current patterns of behavior, can you come up with some kind of experiment to help you cast new light on the situation?

3. OVERCOMING SILO THINKING

Most people agree that silo thinking is bad—and the research on innovation and problem solving backs that up. For complex problems, teams that are diverse outperform teams whose members are more similar to each other.* With reframing in particular, getting an outsider’s perspective on your problem is a powerful shortcut to identifying new framings.

In practice, though, people involve outsiders far less than they should. They may agree with the idea in theory, but when it comes to doing it, they say things like:

- Outsiders don’t understand our business, so it takes ages to explain the issue. We don’t have time for that.

- I’m a leading expert in my field. What’s the point of involving nonexperts?

- I’ve tried asking outsiders, and it didn’t work. The ideas they came up with were useless.

The reactions reveal something important: there are good and bad ways to involve outsiders. To get it right, consider the following story of a leader we’ll call Marc Granger.*

Soon after taking over a small European company, Granger realized he had a problem:

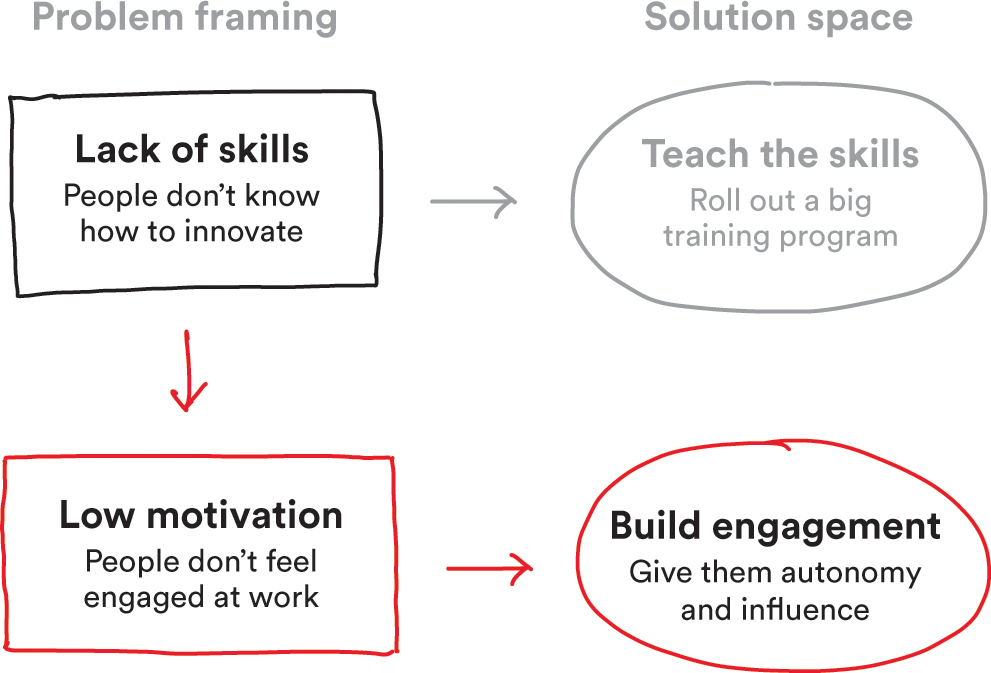

Our people aren’t innovating.

To address this, the management team found an innovation training program that they believed would help. However, as they discussed how to roll out the training program, they got interrupted by Marc’s personal assistant, Charlotte.

“I’ve been working here for twelve years,” Charlotte said, “and in that time I have seen three different management teams try to roll out some new innovation framework. None of them worked. I don’t think people would react well to the introduction of another set of buzzwords.”

Charlotte’s presence in the meeting wasn’t accidental. Marc had invited her himself. “I had only taken over the company about half a year earlier,” he said, “and I knew Charlotte had a good understanding of what was going on in the company. She was the kind of person that our employees came to when they had a problem they didn’t want to take to management directly. I felt she might help us see beyond our own perspective.”

That’s exactly what happened. It quickly became clear to the team that they had fallen in love with a solution—the training program—before they had really understood the problem. Once they started asking questions, they discovered that their initial diagnosis was wrong. Marc: “Many of our employees already knew how to innovate—but they didn’t feel very engaged in the company, and so they were unlikely to take initiatives beyond what their job descriptions mandated.” What the managers had first framed as a skill-set problem was better approached as a motivation problem.

Marc’s team dropped the training program and instead rolled out a series of changes aimed at promoting engagement: things like flexible working hours, increased transparency, and active participation in the leadership’s decision-making process. “To get our people to care about us,” Marc said, “we first needed to demonstrate that we cared about them and were willing to trust them.”

Within eighteen months, workplace-satisfaction scores doubled, and employee turnover—a big cost driver for the company—had fallen dramatically. Financial results improved markedly as people started to invest more energy in their work and took more initiatives. Four years later, the company won an award for being the country’s best place to work.

If Marc hadn’t invited Charlotte into the room, it’s easy to imagine that the management team would have rolled out the training program and suffered the same fate as the three prior management teams. What was it about the process that worked, compared with the many times people struggle to make good use of outsiders? In part it was the type of outsider Marc brought in.

Look for boundary spanners

Charlotte’s existing connection to the team was crucial, and runs counter to conventional wisdom about the power of outsiders. Published success stories on the topic often focus on how tough problems got solved by someone who was utterly unconnected to the issue: None of the nuclear physicists could solve the problem! But then a balloon-animal artist came by.

Stories like those are memorable, and the lesson they offer is backed by research. But as a consequence of hearing such stories, people often think that they have to seek out “extreme outsiders”* who are very different from themselves. Two issues make that approach impractical for day-to-day problem solving:

- It is difficult to bring them in. It takes time and effort to involve extreme outsiders—where, exactly, does one find balloon-animal artists on short notice? Therefore, many people just drop the idea for all but the most vexing, do-or-die problems.

- It requires high effort to communicate. In order to reap the benefits, teams first need to bridge some pretty serious gaps of culture and communication to connect extreme outsiders to the problem.

In contrast, Charlotte was not an extreme outsider. She was an example of what management scholar Michael Tushman calls boundary spanners: people who understand but are not fully part of your world.* Tushman argues that boundary spanners are useful exactly because they have both the internal and the external perspective. Charlotte was different enough from the management team to be capable of challenging their thinking. But at the same time, she was also close enough to understand its priorities and speak its language—and crucially, she was available to get involved on short notice.

Getting outside input is always a balancing act between urgency and effort. With big, bet-the-firm problems, or in situations where you need completely novel thinking, you should invest serious effort in getting a truly diverse group involved. But in the many cases where that’s not an option, think about what else you can do to get some kind of outside perspective on your challenge.

Ask for input, not solutions

As you may have noticed, Charlotte didn’t try to provide the group with a solution. Rather, she made an observation that helped the managers themselves rethink the problem.

This pattern is typical. By definition, outsiders are not experts on the situation and thus will rarely be able to solve the problem. That’s not their function. They are there to stimulate the problem owners to think differently. What that means is, when you bring in outsiders:

- Explain why they are invited. It helps if everyone understands that they are there to help challenge assumptions and avoid blind spots.

- Prepare the problem owners to listen. Tell them to look for input, rather than expect solutions.

- Ask the outsiders specifically to challenge the group’s thinking. Make it clear that they are not necessarily expected to provide solutions.

One other useful effect of having outsiders involved: it forces the problem owners to explain their problem in a different way. Sometimes, the mere act of having to restate a problem in less specialized terms can prompt experts to think differently about it.*

CHAPTER SUMMARY

three tactical challenges

When you use reframing, three common complications sometimes will arise. Here’s advice for dealing with each:

1. Choosing which frame to focus on

Sometimes, reframing will generate many possible ways to frame the problem. To narrow down the list of frames worth focusing on, keep an eye out for framings that are:

- Surprising. Explore surprising problem frames; the surprise arises because the framing challenges a mental model.

- Simple. Prioritize simple problem frames; for most daily problems, good solutions are rarely complex. Use Occam’s razor: simple answers are usually the right ones.

- Significant-if-true. Consider problem frames that would be highly impactful if they were true, even if your intuition suggests they aren’t correct. Remember the Bolsa Familia program.

Keep in mind that you won’t always have to narrow it down to just one frame. It will sometimes be possible to explore two or three framings concurrently.

2. Identifying unknown causes of a problem

When you have no clue what’s causing a problem, one approach is to broadcast the problem widely (we covered this in chapter 6). Two other things you can try:

- Use discovery-oriented conversations. The founders of Sir Kensington solved the ketchup sales mystery through conversations, focusing on listening and learning. Who can you talk to in order to learn more?

- Run a learning experiment. Nickelodeon’s Miah Zinn solved the app sign-up problem by inviting a few kids into the office, instead of relying on A/B testing. In the same way, can you try experimenting with a new behavior, opening the door to new insights?

3. Overcoming silo thinking

In the Marc Granger story, Charlotte’s presence and her willingness to challenge the management team proved crucial. To draw on the power of outside voices, do this:

- Use boundary spanners. Involving “extreme” outsiders can be powerful, but doing so is not always feasible. Luckily, less can often do it. Using partial outsiders (or “boundary spanners”) like Charlotte can provide much of the benefit at a fraction of the effort.

- Ask for input, not solutions. Outsiders aren’t there to provide solutions, but to ask questions and challenge the group’s thinking. Remind everyone about this as you kick off the discussion.

†If you feel you’d benefit from more advice on how to become a better listener, I have provided some recommendations in the appendix, under “Questioning.”