chapter 3

frame the problem

FIRST, FRAME THE PROBLEM

On the monitor of the designer Matt Perry’s computer sits a yellow Post-it with a simple question:

What problem are we trying to solve?

Matt works at Harvard Business Review. Along with Scott Berinato, Jennifer Waring, Stephani Finks, Allison Peter, and Melinda Merino, he is part of the team that created this book. Right after our first meeting in their airy Boston offices, Matt emailed me:

I’ve had this one constant Post-it on my monitor for about a year now. It’s a simple question, but such a helpful reminder on so many occasions. And that’s why this particular note has stuck around (ha!) on my monitor—unlike some others that aren’t as timeless.

At first glance, the emphasis on simply stating the problem seems puzzling. Isn’t it pretty obvious that you need to do that? Why did this particular Post-it get to stick around instead of some other piece of timeless designer wisdom? (“Always dress in black.”)

Talk to anyone who solves other people’s problems for a living—not just designers but lawyers, doctors, management consultants, coaches, or psychologists—and you will find the same strong insistence: start by asking what the problem is.

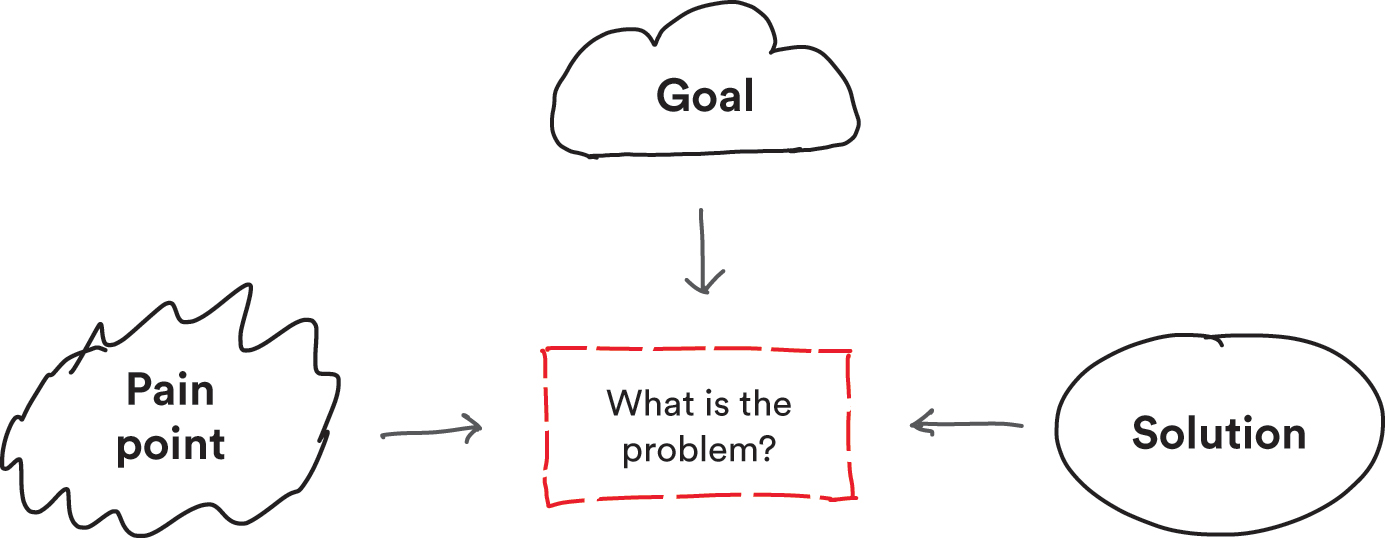

That’s where the reframing process starts too. Simply put, you should:

- Create a short problem statement, ideally by writing down the problem as a full sentence: “The problem is that …” If you work with a group, use a flip chart so everyone looks at the same surface.

- Draw up a stakeholder map next to the statement that lists the people who are involved in the problem. Stakeholders can be both individuals and things like companies or business units.

Keep in mind:

Writing it down is important. Simple as it seems, putting a problem into writing brings a host of important benefits. Do it if at all possible.

Write it down fast. The problem statement isn’t intended to be a perfect description of the issue. It’s simply raw material for the process that follows. Think of it as a slab of wet clay that you plonk down on the table, giving you something tangible to dig into as you start working.

Use full sentences. Using bullet points or one-word problem descriptions makes it harder to reframe.

Keep it short. Reframing works best when you limit the problem description to a few sentences.

* * *

If you decided to work on some of your own challenges, I suggest you pause here and create problem statements and stakeholder maps for each problem before continuing. Use a separate piece of paper for each problem.

WHY WRITE DOWN YOUR PROBLEMS?

There are many benefits to writing down your problem. Here are some of them:

- It slows things down a bit. Writing creates a brief, natural thinking space that redirects the momentum and prevents people from jumping prematurely into solution mode.

- It forces you to be specific. Problems can be strangely fuzzy when they exist inside your head. Putting them in writing creates clarity.

- It creates mental distance. It’s easier to look objectively at a problem once it exists as a physical thing separate from yourself.

- It gives advisers more to work with. It’s easier for advisers to help you when they have a written problem statement in front of them. Writing dramatically expands the number of items people can keep in their mental workspace.

- It creates an anchor for the discussion. When people come up with ideas, you can quickly point to the statement and ask, Does that idea solve this problem? (Sometimes, an idea might make you change the problem statement; that’s fine too. The point isn’t to stick to your first framing but to keep both perspectives—problems and solutions—in view.)

- It creates a paper trail. If you are working for a client, having a written problem statement can help you avoid conflicts down the road. People’s memories are fallible, and without a problem statement, there is a risk that clients will start misremembering what problem they asked you to solve.

WHAT’S YOUR PROBLEM TYPE?

Once you have a problem statement in front of you, the next step is to review it. To prepare for the review, we’ll take a quick detour to the early days of problem-framing research in order to explore some of the different ways problems present themselves.

* * *

In the 1960s, about a decade after the field of creativity research was founded, the influential educator Jacob Getzels made a key observation.* He noted that the problems we’re trained on in school are often quite different from the ones we encounter in real life.

In school, problems tend to present themselves in a nice, orderly manner: Here’s a triangle! If one side is blah blah blah, what is the length of the third side? Conveniently, the problem appears at the end of a chapter on Pythagoras’ theorem, giving us a pretty good idea about how we might solve it. Getzels called these presented problems, ones in which our job is to implement a solution without screwing up too badly along the way.*

In the first jobs we get, presented problems are common: The boss needs an overview of the latest market data. Review these three reports and prepare a summary for her. But as we progress in our careers and start dealing with more-complex matters, problems increasingly appear in three other forms, each of which presents special challenges:

- An ill-defined mess or pain point

- A goal we don’t know how to reach

- A solution someone fell in love with

To master the art of problem diagnosis—Getzels talked about the idea of problem finding—it’s helpful to understand the three types in more depth.

Problem type 1: an ill-defined mess or pain point

Before we formally recognize problems, we feel them, as ill-defined “issues” or pain points.* Some are sudden, dramatic, and acutely felt: Our sales are dropping like a rock. Others are more subtle and slow-burning, carrying a sense of quiet desperation: My career feels like it has stalled. Our industry is in decline. My sister is on a bad path.

Often, the cause of the pain is unclear. Within clinical psychology, for instance, the psychotherapist Steve de Shazer estimated that when starting therapy, two out of three patients initially couldn’t point to a specific problem they wanted to solve.* The phenomenon occurs with workplace problems too. For example, when people say “Our culture is the problem,” it can reliably be interpreted as “We have no clue what the problem is.”

Pain points often cause people to jump to solutions without pausing to consider what’s going on. Here are some typical examples. Notice the effortless move from pain point to solution.

- Our new product isn’t selling. We need to invest more in marketing.

- Surveys show that 74 percent of our staff often feels disengaged. We’ve got to get better at communicating our corporate purpose.

- There are too many safety violations in our factory. We need clearer rules and maybe stronger penalties, too.

- Our employees are resisting the reorganization efforts. We need to roll out some training so they can learn to do as they are told embrace change.

In some cases, the solutions people jump to are based on dubious logic. My stressed-out spouse and I fight all the time. Having a baby or five would surely calm things down around here. More often, though, the solution will seem quite rational, and may have proven effective in other circumstances—only, in this case, it isn’t aimed at the problem you are actually facing.

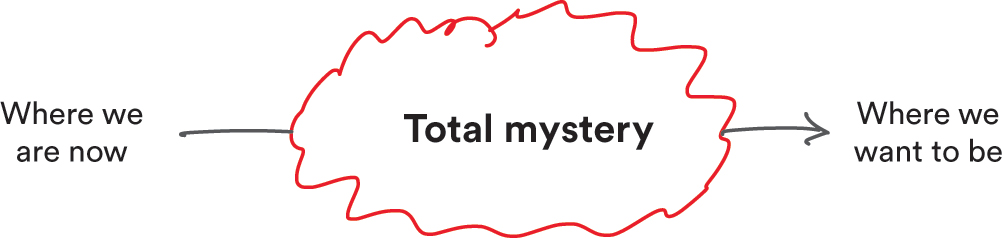

Problem type 2: a goal we don’t know how to reach

Problems can also present themselves in the shape of a hard-to-reach goal.* A classic business example is the so-called growth gap: the leadership team has set a target of twenty million in revenue, but regular sales will get us only to seventeen million. How on earth do we generate another three million in revenue? Mission statements and new-CEO growth strategies are also frequent sources of such goals: we want to become the market leader in X.

When you are facing a pain point, you at least have some kind of starting point to explore. Goals don’t necessarily have that: you may be entirely clueless in terms of where to start. How do I find a long-term romantic partner? My current method of shouting at strangers in the street seems to have some deficiencies.

All you know is that your current behavior won’t suffice. Hard-to-reach goals require people to come up with new ideas rather than sticking to business as usual. (This, of course, is one reason leaders like to set them.)

In a problem-solving context, goal-driven problems are first and foremost characterized by a need for opportunity identification. While opportunity identification has mostly been studied by innovation scholars, not problem-solving researchers, the skills required to do it are nonetheless closely related to reframing and problem finding. For instance, many successful innovations hinge on rethinking what customers really care about, versus what the existing solutions in the market cater to.

Problem type 3: someone fell in love with a solution

The most challenging scenario is when you are presented with a demand for a solution. Imagine a graphic designer’s client says, “I need a big green button on my website.” A novice designer will simply create the button, after which there are pretty good odds the client will come back and complain, “The button didn’t work!” (Or better yet, “When I said green button, you should have known that I really meant red switch.”) If you don’t understand the problem to be solved, giving people what they ask for can be a bad idea.

Once you start looking, you’ll find that the solution-first dynamic is everywhere. Here are a few examples, one of which you’ll encounter later in this book:

- “We should build an app!”

- “I’m dreaming of starting a business that sells Italian ice cream.”

- “I saw this cool website where employees can share their ideas. We should get one of those.”

Sometimes, people have fallen in love with an idea—we should do X!—with zero evidence that the solution they are dreaming of solves a real-world problem. (“What problem are we solving, you ask? Well, making a dent in the universe, evidently.”) This is sometimes called a solution in search of a problem. Those scenarios can be particularly problematic, because a bad solution can do more than just waste time and money. It can also do active harm.

In another popular variation, the solution is disguised as a problem.* With the slow elevator example, for instance, your landlord may come to you and say, “We need to find money to pay for the new elevator. Can you help me figure out what to cut from the budget?”

REVIEW THE PROBLEM

Before applying any specific reframing strategies, it’s a good practice to start with a general review of the problem statement.

Below, I have outlined some questions that can help you do that. The list will start to develop your problem literacy, meaning your general attunement to how problems are framed. The list also highlights typical instances of reframing that weren’t big enough to merit their own chapters, but which are still important to keep an eye out for.

Here are the questions:

- Is the statement true?

- Are there simple self-imposed limitations?

- Is a solution “baked into” the problem framing?

- Is the problem clear?

- With whom is the problem located?

- Are there strong emotions?

- Are there false trade-offs?

1. Is the statement true?

When I share the slow elevator problem, many people forget to ask a basic question about the framing: Is the elevator actually slow?

Somehow, because the tenants say it is slow, this is taken as a fact about the world. But of course, many other things could be going on: it could be a perception issue, an attempt to lower the rent, or something else.

When looking at a problem statement, a good first question to ask is, How do we know this is true? Could this be incorrect?*

- Are our shipments actually arriving late in this market? How is the tracking data created?

- How reliable is this report about weapons of mass destruction?

- Is our son’s math teacher really as incompetent as I think? How did his prior students do in the final exams?

- Is it possible that the reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated?

2. Are there simple self-imposed limitations?

Sometimes, merely by reading the problem description, you will realize that you have imposed an unnecessary constraint on the solution.

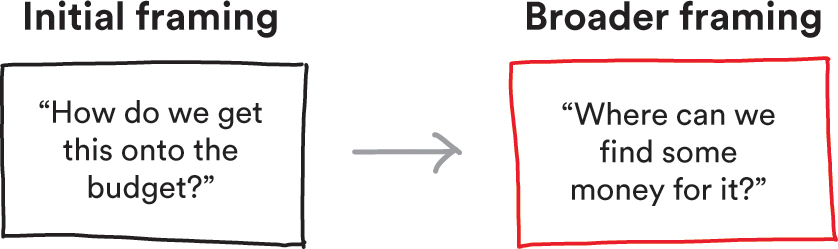

Take the experience of my brother, Gregers Wedell-Wedellsborg.* Back in the early days of the mobile internet, Gregers was working at the Danish broadcaster TV2 when some of his employees came to him with an idea: How about trying to develop content for viewing on mobile phones?

Gregers liked the idea, but faced a problem: since mobile content was unknown territory at the time, there was no established model for making money on it—and TV2 was facing financial cutbacks at the time. For that reason, getting it onto that year’s budget would be a hard sell. Maybe the following year it would be possible.

However, Gregers quickly realized that the problem had been too narrowly defined—because who said the money had to come from TV2’s coffers? He really just needed a bit of cash to start the project. Could that be found elsewhere? He told his team to go outside TV2 to look for potential funding from partners.

The team found the funding. Danish mobile operators were very interested in having TV2 develop mobile content, as the high-volume video content would increase their earnings from data traffic and boost sales of smartphones. The experiment went ahead and eventually launched TV2’s venture into the mobile market, making it a market leader at almost no cost to TV2.

To find self-imposed limitations, simply review the framing of the problem and ask: How are we framing this? Is it too narrow? Are we putting constraints on the solution that aren’t necessarily real?

3. Is a solution “baked into” the problem framing?

Some years ago, I cotaught an MBA elective in which we had the students do an innovation project. Here’s how one of the teams described their project:

We want to develop better nutrition education to promote healthier eating at the school.

The statement contains a glaring assumption: namely that lack of knowledge prevents people from eating healthier food.* That’s a questionable problem framing. The vast majority of business-school students are aware of what is and isn’t healthy. French fries count as vegetables, right? said nobody ever.

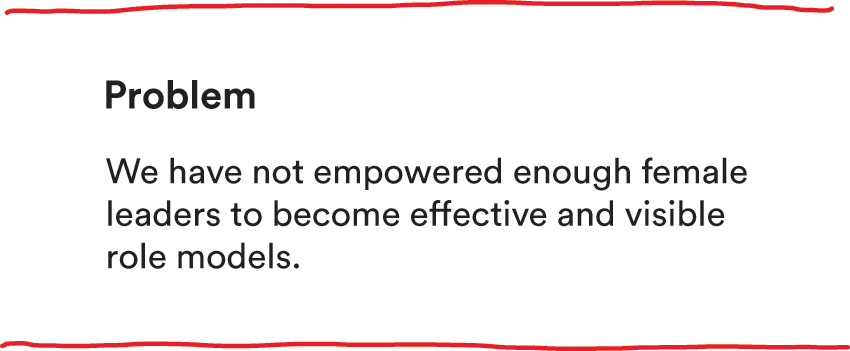

In a similar manner, people often frame problems in a way that points toward a specific solution. Consider this problem statement from a corporate initiative I was involved in that aimed at promoting gender equality.

Notice that a solution—let’s create more female role models—is baked into the initial problem statement. The point is not whether this particular diagnosis was correct. The important thing is to notice the framing, allowing you to question it.

People who don’t do reframing might ask a follow-up question such as, How do we help more women become role models? and thereby get trapped, potentially, in an unhelpful or suboptimal framing.

In contrast, people who are trained in reframing will ask such questions as, Are there other things in play? How about our promotion processes? How about informal connections? Do women get less exposure to senior decision makers?

The mere act of asking those questions makes it more likely you’ll pick a good solution, even if you stick with the first diagnosis in the end.

4. Is the problem clear?

In the previous example, the team had a fairly clear problem statement, which is a good starting point for the reframing process. In comparison, take a look at this one, also from a client:

This statement is not actually a problem. It’s a goal written as a problem, with a bit of added specificity about where they hope the revenue will come from. A “problem” statement like this typically means that the team has to shift their perspective from their problem to identifying a problem that clients care about—such as, what makes it attractive for new clients to sign up? What makes them leave again?

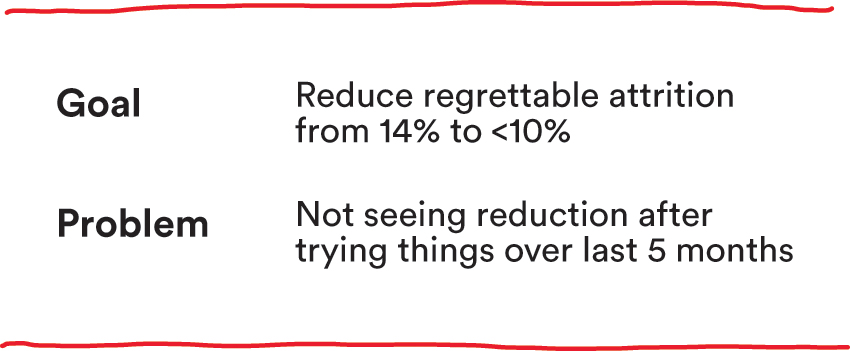

Here is a second example, from a company that was losing too many talented employees to other firms.

This is a typical pain-point statement: we have tried stuff for five months with zero results. A situation like this is likely a good candidate for some reframing. Provided a solution exists, chances are that you’ll find it by rethinking the problem rather than engaging in another five months of trial and error. In a preview of two of the reframing strategies we’ll cover later, you could:

Rethink the goal. Is there a better goal to pursue? For example, instead of preventing attrition, can we do something to lure back our former employees from the competition after they leave? Can we find ways to get more out of the employees while we have them? Can we rethink our recruiting practices to target people who are less likely to leave? If people with a specific profile tend to quit before we have recouped the investment in training them, should we perhaps stop recruiting those people in the first place?

Examine bright spots. Instead of asking why people leave, we could ask why people stay. Looking at our top talent, what is it about our company that makes them say no to more lucrative or more exciting offers? Can we build on those strengths rather than trying to fix our weaknesses? Are there pockets of the business that do not see the same attrition? What might we learn from them? Or how about the people that we managed to recruit from “sexier” companies? What made those people join us? Can we get better at tapping into their personal networks of ex-colleagues, or otherwise turn them into informal ambassadors for our company?

5. With whom is the problem located?

One of the reasons you should use full sentences when describing the problem is that it allows you to spot small but critical details. One such detail is the presence or absence of words like we, me, or they—words that locate the problem.

Is the problem considered to be caused solely by other people? The issue is that the staffers on the night shift are super lazy. Or does the problem owner take some responsibility for the problem as well, like the team with the female role models did? (“We have not empowered …”)

Is the issue framed in a way that relegates it to higher powers or pay grades, safely away from the problem owner’s span of control? We can’t innovate unless the CEO gets serious about it. In the most severe case, no recognizable human agency is found: The problem is that our company’s culture is too rigid.

When we get to the reframing strategy called “Look in the Mirror” I’ll share some advice on how to find more-actionable framings, including that of questioning your own role in creating the problem.

6. Are there strong emotions?

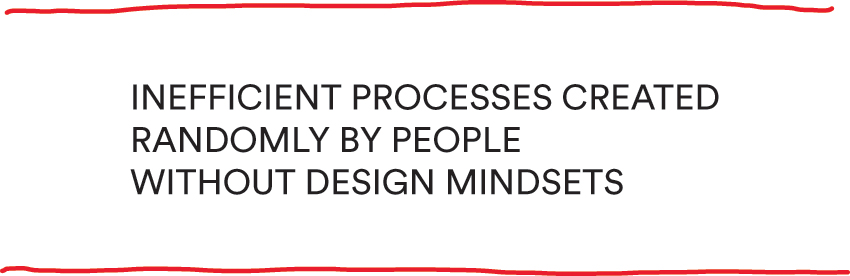

The statements we’ve analyzed so far are mostly neutrally worded. While not necessarily dispassionate, they didn’t exactly convey a sense that epic emotions roared through the veins of the project teams. Compare those with this capital-letter problem statement from a manager who was, shall we say, not the happiest bunny in the forest:

Here’s a helpful piece of advice, shared with me by professor Steven Poelmans of Antwerp Business School: always dig into emotionally charged words. Words like randomly, or the slightly more subtle phrasing people without design mindsets (translation: idiots), suggest that you’ll struggle to solve the problem on a logical or factual level alone.

Furthermore, assumptions that other people are stupid, selfish, lazy, or uncaring always deserve a second, deeper look. Often, what at first seems like complete idiocy is entirely sensible once you understand the reality of the other person. (In other cases, of course, your suspicions will turn out to be amply justified.) We’ll go into more detail on this topic when we get to the reframing strategy called “Take Their Perspective.”

7. Are there false trade-offs?

The most insidious problems present themselves as a trade-off, asking you to choose between two or more predefined options: Do you want A or B?

Poorly framed trade-offs are classic pitfalls for decision makers.* The presence of multiple options creates the illusion of completeness and freedom of choice, even as the options presented may leave out much better alternatives.

In some situations, the people who frame the options are deliberately trying to steer you toward certain outcomes. The US statesman Henry Kissinger, for instance, famously joked about how bureaucrats that wanted to maintain the status quo would present a policy maker with three options: “Nuclear war, present policy, or surrender.”*

More often, though, the options you are presented with aren’t the result of deliberate manipulation. Rather, they are simply assumed to be “natural” either-or trade-offs that everyone is facing. Do you want high quality or low cost? Should your app be easy to use or have lots of customization options? Do you want wide reach or precise targeting in your marketing campaign?

The problem-solving scholar Roger L. Martin and others have documented that creative thinkers tend to push back on such trade-offs. Where other people do a cost-benefit analysis and pick the least painful option, expert problem solvers try to explore the issue in more depth and generate a new, superior option.

The starting point for that is the habit of trying to break the frame, asking How is this choice framed? Are these the only options we have? What is the problem we’re trying to solve?

Here’s the story of how one of the most impressive problem solvers I’ve met dealt with a false trade-off.

FEEDING THE HIPSTERS AT THE ROYAL PALMS

Serial entrepreneur Ashley Albert was in Florida. (It will tell you something about Ashley that she was in Florida to become certified as a judge of barbecue competitions.) During her visit, she noticed that some shuffleboard courts in a local park had been taken over by young hipsters—and they seemed to enjoy the game tremendously.

The encounter inspired Ashley and her business partner Jonathan Schnapp to start a similar venture, The Royal Palms Shuffleboard Club, in Brooklyn’s hipster-rich Gowanus neighborhood. Right away they faced a difficult choice: Should they serve food on the premises?

Anyone with experience in hospitality will tell you that this is a significant decision. Serving food is a huge hassle: there are health inspections, extra staff requirements, and lots of other administrative burdens. Even worse, it’s not very profitable; drinks, especially alcohol, are where the money is. All this suggested that Ashley and Jonathan should stick to just serving beverages.

The problem was, the hipster is known to be a frequent forager. Without food at The Royal Palms, customers would stick around for only an hour or two. That wouldn’t work. Ashley and Jonathan needed people to stick around for the entire evening, allowing them to benefit from the drinking that is so crucial to the hipster’s prolonged courtship rituals.

Most entrepreneurs facing this dilemma end up biting the bullet and just accepting the administrative burdens that come with serving food. Others choose to avoid it, but are then stuck with a venue that’s mostly empty around dinnertime. Ashley decided to see if she could find a third option.* As she told me:

Both of the options we faced were bad. So we started brainstorming on a different problem: How can we get the benefits of serving food without the hassle that comes with it? For various reasons, none of the existing options, like using delivery services or partnering with a nearby restaurant delivery service, would have worked. But we kept mulling over the problem, and eventually we hit on a new idea—something that to my knowledge has never been done before.

Today, when you enter The Royal Palms, you’ll see Brooklynites playing shuffleboard. There will be beards. There will be denim. There will be unique fashion choices. And in the right-hand corner of the club, you’ll see something unusual: an opening into an adjacent garage that Ashley and Jonathan had built. In that garage, one of New York’s ubiquitous food trucks is parked every night, feeding the hipsters.

The solution is brilliant. As the food preparation is done entirely inside the food truck, using the driver’s food permit, Ashley avoided the hassle of getting a food license. At the same time, the model gives Ashley and Jonathan the freedom to select different food types depending on the day and the season.

From the perspective of the food-truck owner, he or she had a captive audience that stuck around all evening, something that was especially attractive in the wintertime. And as Ashley and Jonathan made lots of money on the drinks, they could even offer a guaranteed minimum income to the food-truck owner in case it was a slow night.

Slow nights, however, haven’t been a problem. As I write this, the club is highly profitable, and Ashley has just launched her second shuffleboard club in Chicago. Why Chicago? I asked her. “We need a place with bad weather so people want to stay inside.”

A FINAL NOTE: SAVE THE DETAILS FOR LATER

The seven questions I shared here tend to be helpful, but they are far from the only ones you might ask. As you become more adept at reframing, you’ll gradually add more such patterns to your mental library of problem-framing pitfalls.

Once you have done an initial review of the problem statement, the Frame step of the process is complete (remember the loop: Frame, Reframe, Move Forward). Before we start on the next step (Reframe), I want to make a note about what not to do at this stage. If you have some experience with goal setting, behavior change, or similar disciplines, chances are that some of the statements here made you itch to make them more specific and actionable. What kind of goal is “healthier eating”? That’s way too vague! A better goal would be “Eat at least three pieces of fruit every day, not including French fries.”

The instinct to be clearer about such details is a good one. As shown by decades of research on behavior change, people have much better chances of success if their goals are specific and measurable, and if the required behavior to reach them is clearly spelled out.* Vagueness is the enemy of change.

However, at this point, there’s a trap in giving in to your craving for specificity. If you are too quick to focus on the specifics, there is a significant risk that you will get lost in the details, and forget to question the overarching framing of the problem. You have to zoom out before you dive in: don’t tinker with the specifics of the statement before you are fairly confident that you are looking at the right problem. That’s what we’ll look at next as we delve into the first of the five specific reframing strategies.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

frame the problem

Before you can reframe a problem, you first have to frame it, giving you something to work on. To do so:

- Ask, “What problem are we trying to solve?” This triggers the reframing process. You might also ask “Are we solving the right problem?” or “Let’s revisit the problem for a second.”

- If possible, quickly write a problem statement, describing the problem in a few sentences. Keep it short, and use full sentences.

- Next to the statement, list the main stakeholders: Who is involved in the problem?

Once you have the first framing, subject it to a quick review. Look for the following in particular:

- Is the statement true? Is the elevator actually slow? Compared to what? How do we know this?

- Are there self-imposed limitations? At TV2, the team asked “Where can we find money?” instead of assuming it had to come out of their own budget.

- Is a solution “baked into” the problem framing? Often, problems are framed so that they point to a specific answer. This is not necessarily bad, but it’s important to notice.

- Is the problem clear? Problems don’t always present as problems. Often, you are really looking at a goal or a pain point in disguise.

- With whom is the problem located? Words like we, me, and they suggest who may “own” the problem. Who is not mentioned or implicated?

- Are there strong emotions? Emotional words typically indicate areas you should explore in more depth.

- Are there false trade-offs? Who defined the choices you are presented with? Can you create a better alternative than the ones presented?

Once you have completed the initial review, step 1 (Frame) is done, setting you up to reframe the problem.