chapter 7

look in the mirror

TROUBLE WITH THE KIDS

Can you teach reframing to small kids?

This question brought me to Hudson Lab School, a progressive, project-based school in Westchester, New York. The founders, Cate Han and Stacey Seltzer, knew of my work and challenged me to try running my reframing workshop with their students. So there I was on a warm August morning, teaching reframing to a fidgety bunch of five-to-nine-year-old kids.

The problems of little humans

You might be wondering what kind of problems kids that age have. Well, here’s a choice selection from the workshop, lightly edited for inverted letters, fruit-juice accidents, and squiggly little hearts crowning all instances of the letter i:

- “There was a rock I wanted, but it belonged to someone else.”

- “I can’t beat Electabuzz” (a video-game monster).

- “I can’t hit my sister, because she is smaller than me.”

Yes, of such deep existential problems is the world of little humans composed. (In fairness, the one about wanting someone else’s rock could be said to underlie pretty much every human conflict since the Peloponnesian War.) And as I ran the class with Stacey, Cate, and their colleagues, it became clear that most of the kids—especially the younger ones—struggled with the concept of reframing.

Take the case of a kid I’ll call Mike, whose brother would sometimes hit him when they fought. Mike’s problem statement was succinct:

I can never get revenge.

His chosen solution was similarly straightforward:

Hit on head first.

Based on my workshop, Mike realized that he might benefit from developing an alternative approach. After some hard thinking, he came up with:

Don’t hit.

Despite Mike’s valiant efforts, one sensed a certain systemic drift toward the first solution. I suspect Mike and his brother’s conflicts continued to be solved through realpolitik rather than reasoning.

And yet, there were exceptions. Try for a second to step into the socks of Mike’s classmate, a seven-year-old girl I’ll call Isabella, and consider how she might reframe her problem:

My five-year-old sister, Sofia, constantly asks me to come upstairs and watch television with her. This is very annoying.

At first, Isabella leapt to the conclusion that the problem was her sister’s personality: Sofia is an annoying person and thus, she naturally enjoys pestering her poor sister.

In doing so, Isabella illustrated what’s called the fundamental attribution error, a noted phenomenon in psychology in which we instinctively conclude that people do bad things because they are, at heart, bad people.* My spouse is selfish. Our customers are stupid. People voting for the other side just want to see the world burn.

It’s an easy perspective to take—in fact, we do it automatically—and left to her own devices, that’s probably what Isabella would have continued to think. But as she started questioning her problem, gently prodded by one of her teachers, she came up with two alternative framings:

Reframe #1: How can I feel less annoyed with Sofia?

Reframe #2: How can Sofia be less lonely?

In the first reframing, Isabella turned her attention to herself, exploring how she could manage her own emotions. In the second reframing, she stepped beyond the simplistic “she’s just annoying” view and did something borderline remarkable: she started seeing her sister in a kinder, more human light.

In the next chapter, we’ll take a closer look at how you can solve problems by taking someone else’s perspective, deliberately working to truly understand them. Before that, we’ll look at one of the most overlooked sources of insight: our own contribution to the problem.

Look in the mirror: What is my own role in creating this problem?

The strategies we’ve covered so far were all about seeing something that was hidden outside the frame—a bright spot, a higher-level goal, or a missing stakeholder.

This chapter, in contrast, is about a factor that tends to be hidden in plain sight right inside the frame—and that’s you. When considering problems, we too often overlook our own role in the situation, as individuals or as a group.

Perhaps this is not surprising. Since childhood, we’ve learned to tell stories that conveniently leave out our own agency. Windows and vases break. Siblings spontaneously start crying. Milk-laden glasses, tired of their table-bound existence, fling themselves to the floor.

Research shows that this pattern continues unabated into adulthood.* Examples of this abound. Here I’ll mention a story that’s 1) very possibly anecdotal and 2) too good not to share anyway. Reportedly, a 1977 newspaper article looked into what drivers wrote in their insurance-claim forms after they’d been in a car accident:*

- “A pedestrian hit me and went under my car.”

- “My car was legally parked as it backed into the other vehicle.”

- “As I reached an intersection, a hedge sprang up, obscuring my vision.”

Whether anecdotal or not, the quotations capture something true: we’re consistently pretty terrible at seeing ourselves clearly—and we reliably fail to take our own actions into account when faced with a problem.

Three tactics for looking in the mirror

The good news is, there are things we can do to get a more accurate perception of ourselves. Here are three tactics for better uncovering your own role in problems:

- Explore your own contribution.

- Scale the problem down to your level.

- Get an outside view of yourself.

I should warn you, however, that this strategy can be more painful than the others. It’s not too taxing to look outside the frame or rethink goals, and identifying bright spots can be positively delightful. But taking a long, hard look in the mirror, honestly confronting our own role in a problem, can be uncomfortable. Like a dentist’s appointment, some people will go to great lengths to avoid it.

My advice: accept the discomfort.* Our capacity to recognize painful truths can at times generate some of the most liberating solutions. In fact, some of the best problem solvers I’ve met don’t just embrace or accept the pain of self-reflection. They actively seek it out, because they know that it carries the promise of progress.

1. EXPLORE YOUR OWN CONTRIBUTION

Have you ever used a dating app or a dating website?* If you have, you might have noticed that people’s written profiles change over time, reflecting their experiences with the app.

As people first create a profile, they write the usual happy inanities: I like puppies, motorcycles, and long walks on the beach. Soon after, though, details are added to their profile that tell you something about how their first couple of matches went:

- Please write more than “What’s up?” when you message me.

- Please look like your pictures.

- If you don’t look like your pictures, you’re buying me drinks until you do.

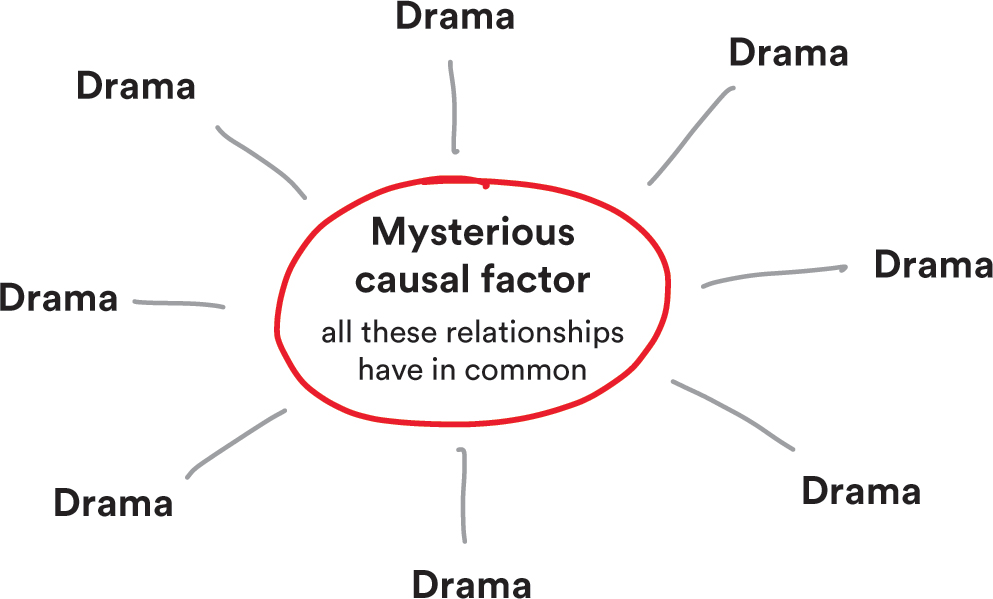

Then there are the “no drama” people.* These are the men and women who write on their dating profiles, “I’m not into drama”—or as they sometimes put it: “NO DRAMA!!!!!” When you see this on someone’s profile—especially the CAPS LOCK version—you can surmise that they have experienced a good deal of drama in their past relationships.

Now, why might this be? Innocent explanations include that they’ve been unlucky, or that they happen to live in an area with lots of drama-prone people. But at the same time, one can’t help but suspect a more tantalizing possibility: they are the ones causing the drama, or at least cocreating it.

Even if they aren’t creating the drama, it’s likely that they tend to select for partners that create drama—which should perhaps prompt a review of whatever filtering methods they use to pick their dates.

I share this example because our lives can sometimes provide similar clues about how our own behavior might play a role in creating the problem: Nobody ever gives me honest feedback. Well, not since I fired that guy who whined all the time.

When facing a problem, take the time to ask: Is it possible that my (or our) own behavior is, on some level, contributing to the problem?

- Headquarters/legal/compliance rejects almost every single idea we send them! Should we rethink the way we develop or pitch our ideas?

- Our salespeople are super sloppy. They make lots of errors in their reports, and they turn them in late. Might our reporting forms be in need of simplification? Can we process them differently?

- Our employees are not very good at collaborating with each other. What are we, as leaders, doing to create that behavior?

- I constantly have to tell my kids to put down their electronic devices. Is it possible I was telling them this while checking something on my phone?

Avoid the word blame

As you can probably sense, looking in the mirror can be challenging in practice. This goes double when a group is involved—because often, the problem was caused by someone in the room. (Or worse yet, the problem is someone sitting in the room.)

One helpful way to make the discussion easier is to avoid the word blame, and instead talk about the idea of “contribution.” This advice comes from the management classic Difficult Conversations, coauthored by Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen of the Harvard Negotiation Project.* As Sheila told me:

Asking “who’s to blame” can be problematic, because it really means, Who messed up and should be punished? The word blame suggests that someone did something that was objectively “wrong”—say, breaking a rule or acting irresponsibly. Contribution doesn’t have that assumption: much of what you contributed might have been perfectly reasonable, but it still didn’t help. Contribution is also a more forward-looking perspective, because it tells us what we would have to change to do better next time. And crucially, it recognizes that mistakes are typically the result of more than one person’s actions. Yes, you taking the wrong turn made us miss the flight. But in fairness, if I had booked a later departure, we would have had more room for error.

Recognizing that several people contributed to a mistake, however, doesn’t mean their contributions are evenly distributed. It still can be mostly one person’s actions that created the result. The important part is to see the problem as a system, so you can identify all possible avenues of improvement instead of focusing on just one person’s actions. As the inimitable Swedish statistician Hans Rosling put it: “Once we have decided who to punch in the face we stop looking for explanations elsewhere.”*

Here’s how one leader from the oil and gas industry, John, practiced it back when he managed a factory:

When something had gone wrong on the factory floor, the involved parties were called into my office to talk it over and figure out how we could do better. In that situation, people are naturally worried about being blamed, leading to some defensiveness—and that’s really not a good way to prevent future problems. So I made a habit of always opening the conversation with a specific question: Tell me how the company failed you.*

The question had a powerful effect on people, as they understood that the boss wasn’t just looking for someone to blame. John’s openness would prompt them to reciprocate by exploring their own contributions as well as those that were external, leading to a productive conversation about how to prevent the problem from recurring. By focusing on contribution rather than blame, and by being open to the possibility that mistakes have multiple parents, John and his employees jointly managed to create significant improvements at the factory.

2. SCALE THE PROBLEM DOWN TO YOUR LEVEL

There is a deep temptation to frame problems at a level where you can’t really do anything about them:

- We can’t innovate until the CEO decides to make it a real priority.

- Moving faster? Our corporate IT system would need a major overhaul before that could happen.

- I’ll start writing my prize-winning novel the second I can afford a new laptop, some professional writing software, and a half-year sabbatical at a little lakeside cottage in Italy.*

The insistence on a systems-level problem framing can lead to “boil the ocean”–type efforts or paralysis through sheer fatalism. Author and columnist David Brooks puts it like this: “To make a problem seem massively intractable is to inspire separation—building a wall between you and the problem—not a solution.”*

To counter this, remember that there are often things you can do at your own level even when the problem seems big. The critical tactic is to scale the problem down, asking, Is there a part of the problem I can do something about? Can I solve the problem at a more local level?

A “wicked” problem: corruption

Consider corruption. As you’ll know if you’ve ever lived in a country plagued by corruption, this social pathology touches almost every aspect of society, including the cultural norms—everyone is doing it, so why shouldn’t I—making it very hard to combat. Corruption has been called a “wicked” problem, which is not surfer-speak for a really awesome problem, but a term for challenges that are so complex as to be almost unsolvable.*

And yet, people within a corrupt system sometimes find ways to fight back on their level. One inspiring case comes from Ukraine’s health-care system.* As described by the journalist Oliver Bullough, the supply chain for Ukraine’s hospitals used to be a hotbed of corruption. Every time the hospitals needed to buy medicines or medical equipment, a number of corrupt middlemen siphoned off cash, resulting in vastly inflated prices and missing equipment. That would be bad for any business. When that happens in a hospital, patients needlessly suffer and sometimes die.

The situation abruptly changed for the better when some civil servants in Ukraine’s health ministry pushed through a policy change. How? They outsourced the purchasing of medicine to foreign agencies at the United Nations, thereby cutting out all of the corrupt middlemen in one stroke. The initiative, Bullough writes, saved hundreds of lives and led to $222 million in savings.

Ukraine still suffers from severe corruption issues. But in one small way, the problem was partially solved because bureaucrats, accountants, and health-care experts decided to see what they could do at their level, rather than accepting the status quo. In the same way, can you reframe the problem in a way that allows you to act on it?

3. GET AN OUTSIDE VIEW OF YOURSELF

In her book Insight, the organizational psychologist Tasha Eurich draws an important distinction between internal and external self-awareness.*

- Internal self-awareness is when people are in touch with their own emotions. This is what people normally think of as “knowing yourself”: being deeply attuned to your own values, goals, thoughts, and feelings.

- External self-awareness, in contrast, is your awareness of how other people see you. Do you understand the impact your behavior has on the people you engage with?

Eurich’s point is that the two qualities aren’t necessarily linked: someone can have spent the last six months on a mountaintop, serenely meditating on their core values and beliefs, and still be utterly clueless about the fact that everyone around them thinks they’re arrogant and uncommunicative.† To solve people-related problems, try to become more aware of how you come across to others.

How to ask for input on yourself

My friend and fellow author, the social psychologist Heidi Grant, has a simple tip for how to do this.* Find a good friend or colleague and ask that person: “When people first meet me, what impression do you think they get—and how do you think it differs from the way I really am?”

As Heidi says, “The questions will give you some immediate insight into sides of yourself that you may not have been aware of. And by asking them about a stranger’s perceptions instead of their own, you open the door for people to share less positive opinions as well.” (Well, Bob, I think people might mistake your general mediocrity for extreme incompetence.)

By the way, you may notice that this tactic is different from the other ones I’ve shared: it focuses less on the problem at hand and more on yourself. By improving your external self-awareness, you will gain an edge both with regard to your current problem and to all future problems you come across. (Consider this an added incentive for trying out Heidi’s question.)*

Overcoming power blindness

If getting honest feedback from your peers can be hard, getting it from people you lead can be even harder—and not just because the power imbalance may make them less likely to give you honest feedback. Columbia University psychologist Adam Galinsky and his colleagues have demonstrated that having power makes people less capable of understanding others’ perspectives.*

To remedy that and get a truly accurate perspective on a problem involving your employees, you may need to draw on outsiders. Here is an example from a company that did that.

Chris Dame reframes a usability problem

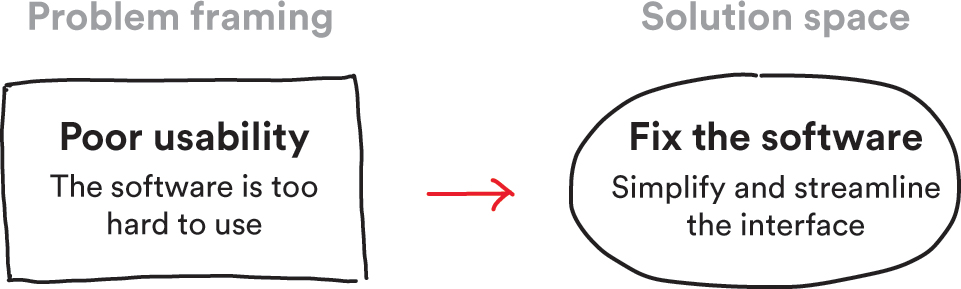

Remember Chris Dame, the designer who worked on Stephen Hawking’s wheelchair? Some years ago, Chris was brought into a Fortune 500 company to help solve a problem. Specifically, the client had recently bought a software platform that allowed the company’s employees to share knowledge and resources across different projects. The problem was, nobody actually used the system. As Chris told me:*

Based on their own conversations with their employees, the client came to us thinking they had a usability problem. People had told them things like, It’s too much of a hassle to put in the information. I simply don’t have the time to get it done. That framing of the problem suggested they had to simplify the system, which is more or less what we had been called in to do.

Chris, however, understood the importance of questioning that diagnosis:

In my experience, when clients come to me with a problem, four out of five times, there is something about the problem that needs to be rethought. In maybe one of those four cases, the problem they are initially focused on solving is flat out the wrong problem.

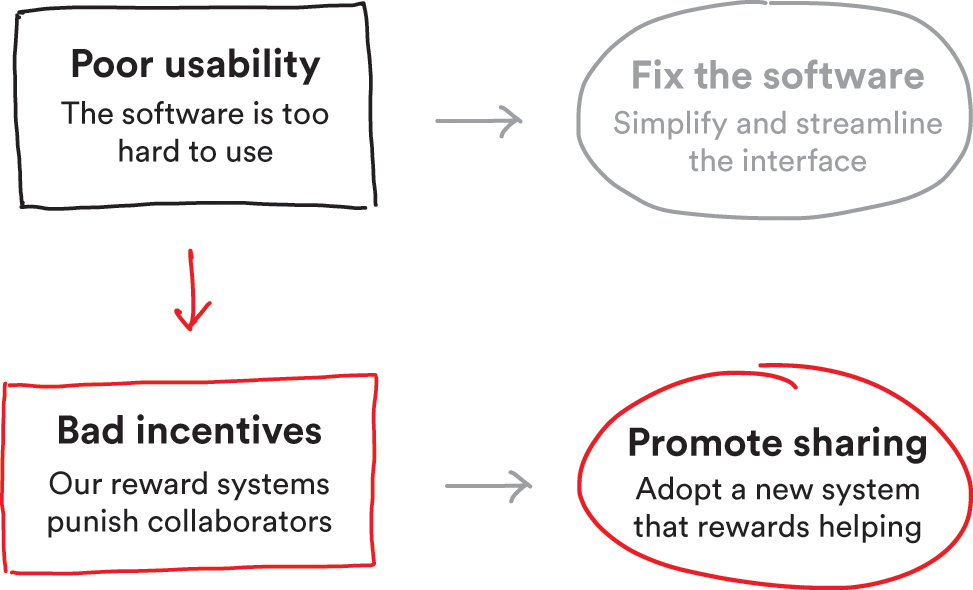

For that reason, Chris started by setting up a series of small workshops in which he could explore the problem together with the employees, without the presence of the senior executives:

Once they were free to talk to an outsider like me, off the record, a quite different problem came to the surface. Basically, people felt there was job security in hoarding information—and that sharing their knowledge and contacts put them at risk for being replaced, while not providing any career benefits.

Chris learned this wasn’t just a perception. The company mainly rewarded and promoted people based on which projects they had been part of. As a result, everyone constantly hustled to get onto the winning projects, while having no incentive to help anyone else.

The insight led the client to change its incentive system. The company created a new metric, an “expert rating” that measured how many colleagues you had helped and how happy they were with your help. This expert rating was made visible to everyone else, creating a public way of acknowledging high-value contributors—and crucially, the management team also started using the expert ratings in their promotion decisions. Once the new solution was implemented, employees started using the knowledge-sharing platform to great effect.

A note on corporate self-awareness

While Tasha Eurich and Heidi Grant’s observations pertain to individuals, they carry over quite well to the corporate level. Just like people, companies can have a strong corporate culture and explicitly defined values, and still remain clueless about how others—not least customers and prospective employees—actually see them.

Often, the image isn’t flattering. Fairly or not (and I’d argue that it’s often unfair), big institutions—especially for-profit companies, but also governmental organizations—are generally viewed in a negative light by the public. As my colleague Paddy Miller liked to put it: “When did you last see a Hollywood movie where a big corporation was cast as the good guys?”

For people working in large companies, facing this reality can be demoralizing. Employees of pharmaceutical companies, dedicating their careers to saving lives, are deeply troubled when they realize that some consumers see their corporations as being less trustworthy than tobacco companies. People who go into public service to do good are confronted with deeply jaded stereotypes about politicians and the public sector. Startups that grow big and successful may well continue to think of themselves as scrappy outsiders doing good work and fighting the ornery incumbents—all while their customers gradually shift to seeing them more like the incumbents.

In all of these cases, taking a hard look in the mirror is an essential step in making things better—even if it’s a painful process to go through.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

look in the mirror

Revisit your own problem statements. For each problem, do the following:

Explore your own contribution

Recall the idea of focusing on contribution rather than blame that Sheila Heen and her coauthors talk about. Problems can be the result of multiple people’s actions, including yours.

- Ask yourself: What is my part in creating this problem?

- Even if you don’t contribute to the problem, ask whether you can react differently to it (recall how seven-year-old Isabella did this with her younger sister).

Scale the problem down to your level

Problems can exist on many levels at once. Corruption, for instance, exists at a personal level, an organizational level, and a societal level. Not all problems are caused by your actions or at your level—but that doesn’t mean that a problem can’t be addressed at your level, at least in part. For problems that seem too big to solve, ask: Is there a way to frame the problem that makes it actionable at my level?

Get an outside view of yourself

Remember the concept of external self-awareness: How do you come across to other people? To map this more accurately:

- Ask a friend to assess how strangers might see you.

- If you are a leader—or if you are exploring a corporate-level problem—consider getting the help of neutral outsiders to gain an external view of the organization.

Finally, with all three tactics for looking in the mirror, be prepared for possibly unpleasant discoveries. Sometimes you need to go through a bit of pain to find the best way forward.

†At this point, some people go “I had a boss just like that!” In the spirit of this chapter: if that’s you, maybe also consider if one of your subordinates ever felt the same way.