Day 4: Meter, Time & Beats

Meter is the division of beats into equal groups.

Here is a pulse made up of 6 quarter notes:

A simple quarter note pulse

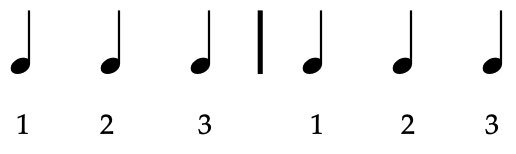

Although it’s quite simple, it can be played in various ways. Let’s try one possibility where the 6 quarter notes are divided into 2 groups of 3 quarter notes.

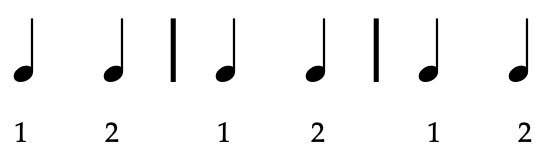

Now let’s try a different one. This time the pulse is divided into 3 groups of 2 quarter notes:

These pulses are very different in their musical effect. But how did we distinguish that these two are different at all?

The answer is in the accents

. Just like in everyday language where some words are more stressed than others, in music, some beats are stronger than others. Put simply, some beats are accented

.

In the first example above, the 6 quarter notes are divided into 2 groups of 3 beats each. The first beat of every group is stronger than the other two. It is accented. And so, we perceive the meter as being in three,

meaning that the pulse has a recurring one, two, three, one, two, three, etc.

effect. Another term for in three is to say that it is a triple meter

.

In the second example, the strong beat appeared every 2 beats and so we perceive the meter to be in two

. Its effect is of a recurring one, two, one, two, etc.

, where the one is strong (accented) and the two is weaker. Another term for in two is duple meter

.

These cycles of strong and weak beats are better known in music as meters

. They can be in any number of beats, but the most common are the ones in two (or duple meters), in three (or triple meters), and four (or quadruple meters).

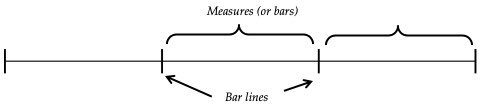

In musical notation, these groups of beats are organized into measures

(also known as bars

) and separated by bar lines.

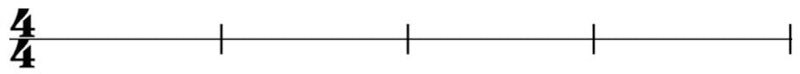

Measures (or bars) and bar lines

Time Signature

To indicate the meter quickly and clearly in musical notation, we use time signatures

. A time signature consists of two numbers, one sitting on top of the other:

In sheet music you’ll find a time signature at the beginning of the music.

So, what do these numbers mean?

The number on top tells us the number of beats per measure.

It tells us whether the meter is in two, three, four or more. The time signature 2/4 shows us that the meter is in two; there are two beats in every measure.

The bottom number tells us what those beats are worth

. It shows us whether the beats are eighth notes, quarter notes, half notes, or any other note value.

This bottom number is relative to the whole note.

The easiest way to work out what the beats are worth is to divide the whole note by that bottom number. For example, if the bottom number is a 2, work out ‘a whole note divided by 2’ and that results in two half notes. So, when the bottom number of a time signature is a 2, the beats are half note beats.

What about a four as the bottom number? The whole note divided into 4 gives us 4 quarter notes. So, a time signature with 4 as the bottom number represents a quarter note pulse.

Bottom Number / Value of the Beat

1 / whole note beat

2 / half note beat

4 / quarter note beat

8 / eighth note beat

16/ sixteenth note beat

and so on.

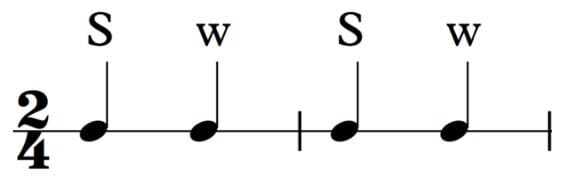

The time signature two-four indicates that the meter is 2 quarter beats per measure. This is a duple meter,

which means that it’s made of two recurring beats – the first beat is the strongest, the second being the weaker.

Note that the time signature is not a math fraction although it does look like it. This is why we do not say ‘two fourths’ but simply ‘two-four’. In this book, time signatures are referred to by the numbers connected by a dash (-), such as the ‘two-four’.

Let’s look at another example. This is the time signature three-eight:

Since the top number is a three, then we know that this meter consists of 3 beats per measure. It is a triple meter.

Now we need to figure out what kind of beats they are. Since the bottom number is an eight, then they are eighth notes.

Three-eight is a triple meter of 3 eighth note beats per measure.

And what about the time signature two-two:

The number on top tells us that there are two beats per measure. What kind of beats? The bottom number, also a two, indicates that they are half note beats. Therefore this meter is a duple meter

and it consists of two half note beats per measure.

Now try it out for yourself. Before we move on, define this time signature:

——————————

Answer

The bottom number tells us that the beat is a quarter note beat. How many quarter note beats per measure? From the top number we know that it’s four. So this is a quadruple

meter

that consists of four quarter note beats per measure.

You might have noticed that some time signatures are very similar. For example, two-two and four-four both hold the same amount of notes in a measure, and two-four and two-two are both duple meters. We’ll discuss this issue in more depth at a later stage.

Strong & Weak Beats (Accents)

As we’ve mentioned, meters are made up of a fixed layout of strong and weak beats. However, don’t let the words “strong” and “weak mislead you. They are terms that allow us to explain this particular aspect of rhythm. There is nothing better with strong beats, or worse with weak beats. They are both equally important. It is with these two together that meter works. Indeed, the strong beats wouldn’t be strong at all if we didn’t have the weaker ones to compare them with.

In duple meters, the first beat is the strongest while the second is weak. The example here is in two-four meter but the same applies to any duple meter such as two-eight or two-two.

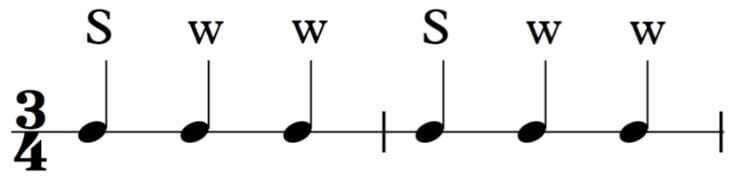

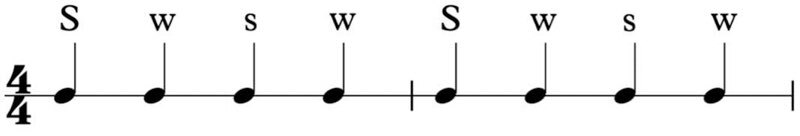

In the following diagrams, ’S’ stands for strong and ‘w’ stands for weak.

In triple meters, the first beat is the strongest and it is followed by two weak beats.

In quadruple meters, the first and third beat are strong and the second and fourth are weak. The first beat, however, is stronger than the third so the four beats are: Strongest, weak, strong, weak.

It’s important to note that these strong and weak beats are not forced by musicians. They occur naturally within melodies, chord progressions, accompaniments, and so on because music is naturally made up of patterns.

At the same time, the impression of strong and weak beats of a meter is often altered according to the flow of the music. A strong beat can be felt earlier or later than expected. In fact, this is a common way of giving the music a sense of variety. We’ll see some examples of this on day 15, but for now it’s important to understand this theoretical outline of strong and weak beats.

Expert Tip: Meter in Practice

So what can we do with this knowledge of meters? Let’s take that last time signature as an example and compose a rhythm. Here we have four empty measures of four-four time:

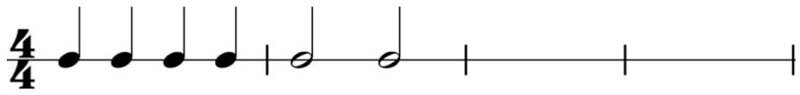

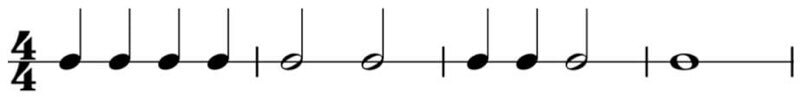

From our discussion of time signatures, we know that there are four beats per measure and each of those beats is worth a quarter note. Let’s fill our first measure with 4 quarter notes:

We also know that two quarter notes equal one half note, so we can fill the next measure with two half notes.

For the next measure, let’s mix it up. We’ll fill the first two beats with a quarter note each and we’ll fill the rest of the measure (two beats) with a half note:

Now let’s finish with a long note. Since one whole note is equal to four quarter notes, the whole note can fill up an entire measure in this meter. Our four-measure rhythm is complete: