So far, we learned what the notes of the white keys on the piano are called. We learned that there is a pattern of 7 letter names given to 7 pitches and they go from A

all the way up to G

. (Or in the other direction, from G

all the way down to A

).

The black keys, of course, are the other 5 notes (out of the 12) of our musical alphabet. These five new notes are also named using the alphabet from A

to G

, but in order to distinguish the differences between them and the white keys, we add accidentals.

There are three basic accidentals and their function is to raise or lower a note by one half step.

Let’s look at the first two accidentals and their symbols that are used in musical notation: the sharp and the flat.

The Sharp

The sharp is this symbol:

The sharp’s job is to raise the pitch of a note by a half step. This means that putting a sharp next to a note, gives us the note that is immediately above it. This new note will have two parts to its name: the letter name of the original note and the word sharp

.

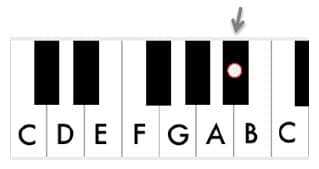

For example, putting a sharp next to the note C

will give us the note C sharp

(or we could write it as C

#) and its sound will be a half step higher than the note C

.

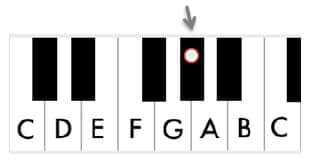

Similarly, G sharp

is a half step higher than G

.

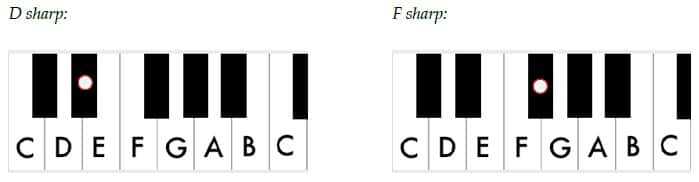

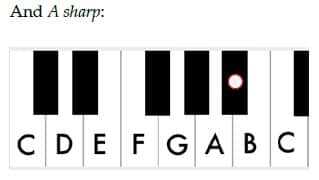

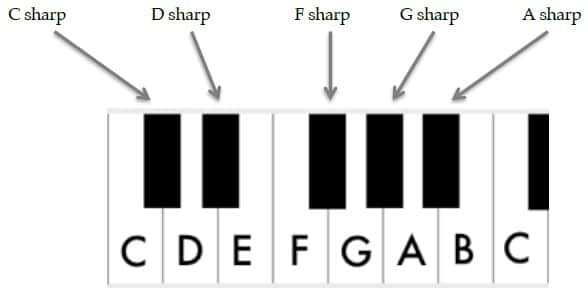

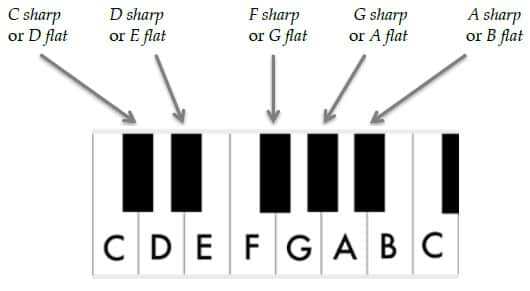

And so on and so forth, the names of the remaining black keys are as follows:

With the addition of sharpened notes our musical alphabet now consists of 12 different notes:

The 12 notes of the musical alphabet

The Flat

The second type of accidental is called the

flat

and this is its symbol:

While the sharp raises the pitch by a half step, the flat lowers it by a half step.

This means that putting a flat next to a note, gives us the note that is immediately below it. Just like before, these new notes will have two parts to their name: the letter name of the original note and the word flat

.

For example, putting a flat next to the note B

will give us the note B flat

(or we could write it like: Bb

) and its sound will be lower than B by a half step.

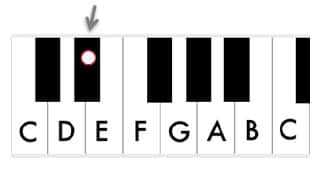

This key is E flat.

It sounds a half step lower than the note E.

Continuing with that pattern, our 12 tone musical alphabet is now complete. We have our usual 7 white keys named after the first 7 letters of the English alphabet and 5 black keys, each one with 2 possible names:

The names of all 12 keys of the musical alphabet

If you are wondering why we are renaming the black keys with flats once we’ve already learned their names with sharps. This is because the 5 notes that are the black keys on the piano have two alternate names: one with a sharp and one with a flat. This concept is called

enharmonic equivalence

and it’s explained fully in the next pages.

Enharmonic Equivalence

Enharmonic equivalence is the fancy term for having two different names (or two different spellings) for one sound (one musical note).

The reason that some notes have 2 alternate names is because of how the concept of the sharp and flat works. The sharp raises any

note by a half step, while the flat lowers any

note by a half step no matter what the original note being altered is. So, the note that is a half step higher than D,

for example, is a D sharp.

But at the same time, that same note is a half step lower than E

so its name could also be E flat.

It’s a common misconception that only the white keys can be sharpened or flattened and that only the black keys are named as sharps or flats. In reality, any note can be raised or lowered: whether it is a B

, an F

, an E

, a G,

etc. or even an E flat

, a C sharp

or any other black key.

For example, sharpening the note E

will give us the note E sharp

. And, of course, this is an enharmonic equivalent of the note F.

This means that F

and E sharp

are two names for the same sound. The question of which name to use for the note depends on context. This is a more advanced issue and so we don’t need to worry about it here.

The Natural

What happens if we need to raise a flattened note? Or lower a sharpened note? How does an altered note go back to the original, unaltered note?

This is where the third accidental becomes useful. Its name is the natural

and it is written like this:

Its job is to cancel a sharp or a flat

that has appeared before. For example, if we need to write the notes C sharp

and then C

, we make our intentions clear that the second note is not sharpened (that it is not another C sharp

), by using the natural. Without this accidental, a note could easily be misinterpreted.

The natural is also used to cancel out a flat. For example, if we need to write the note E flat

followed by the note above it, E

, we use the natural to make it clear that this second E

is not flattened too.

The natural, therefore, has the power to both raise and lower notes. When it cancels a sharp, it lowers the note by a half step

and therefore takes it back to the original. When it cancels a flat, it raises the note by a half step

and takes it back to the original.

The Double Accidentals

We mentioned earlier that flattened notes could be flattened further, and sharpened notes sharpened further. This is where the double sharp

and the double flat

come in. These accidentals are not as common as the other three but they are good to know anyway.

The Double Sharp

The symbol for the double sharp is this:

Its job is to raise the note by a whole step

. For example, double sharpening the note F

produces the note F double sharp.

The F double sharp

is an enharmonic equivalent of the note G

.

The Double Flat

The symbol for the double flat is this:

Its job is to lower the note by a whole step.

For example, double flattening the note E

produces the note E double flat

and it is an enharmonic equivalent of the note D.

Due to all these accidentals, any note out of the 12 can have at least one alternate name – that is, an enharmonic equivalent.

Notating Accidentals

Accidentals are written on the left of the note, in line with the note head, and they remain in effect for the whole measure.