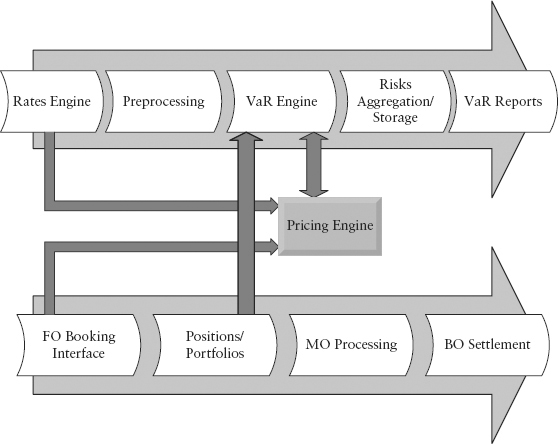

FIGURE 3.1 Stylized System Architecture

Before we explore the different VaR methodologies in Chapter 4, we need to introduce the building blocks used by VaR calculation—in particular, how positions in a portfolio are mapped to a set of risk factors and the generation of scenarios from these risk factor data. This preprocessing step represents the data aspect of VaR and forms the crucial first half of any VaR system.

To gain a perspective of how banks build and maintain their risk management systems, it helps to look at a typical risk management architecture. A good design incorporates the so-called front-to-back architecture within a single system. Unfortunately because of the merger mania in the late 1990s, many banks inherited legacy systems that were then interfaced together (loosely) by their in-house risk IT. In addition, the outsourcing mania in recent years may have moved the risk IT support to a different continent. Such a disconnect creates many weak links in the information chain. Some of the resulting problems could be incomplete position capture, incompatible rates and risk factors across systems, lack of risk aggregation tools, and so on. In the extreme case, risk information becomes opaque and questionable, which could lead to problems in hedging activities and risk monitoring.

Figure 3.1 shows a stylized system architecture. The upper part represents the risk management system while the lower part represents the trade booking system. Both systems call on the pricing engine, which consists of pricing libraries (models and codes) used to revalue a derivative product. Think of it as the brain that computes the fair price of each deal as you pass it through the engine.

FIGURE 3.1 Stylized System Architecture

The front-office (FO) booking interface lets the trader price and book deals. It invokes the pricing engine to get real-time pricing, risk, and hedging information. To value a product, the pricing engine requires rates information from the rates engine and deal information from the booking interface (see the bent arrows).

Once the trade is booked, the position is stored in portfolios (hierarchical database). Typically, each trading desk has multiple portfolios. A cluster of portfolios gets rolled up into a book for that trading desk.

Deal information such as profit-loss (PL) and cash flows are passed to middle office (MO) for processing. Some of these support functions include a product control team, which performs daily mark-to-market of trades, price testing, and PL attribution. The verified PL is then passed on to the finance team that does management accounting. Finally, the back-office (BO) processing team performs deal verification, post-trade documentation, and cash settlement with the bank’s counter parties.

The rates engine takes in real-time market data feeds from sources such as Reuters and Bloomberg and stores the data at end of day (EOD data snapping). In the preprocessing step, the universe of data is cleaned and bootstrapped (for yield curves), and deals are mapped to a set of risk factors. From the risk factors, the preprocessor will generate a set of scenario vectors (for historical simulation hsVaR) or a covariance matrix (for parametric pVaR).

Next, the risk engine (or VaR engine) calculates the PL vectors for all positions in the case of hsVaR. Here, the pricing engine is called to perform full revaluation of each deal (using positional and rates information). In the case of pVaR, the covariance matrix is multiplied with the sensitivity vector directly to obtain pVaR. Here, the sensitivity vector is computed by the pricing engine as well.

Once the output of the VaR engine—the PL vector or covariance matrix—is generated, these risk results need to be stored at a chosen level of granularity. Clearly, it is ideal to have information as granular as possible (the finest being risk per deal by risk factor) so that the risk controller can drill down with a fine comb for analysis. In practice, this is constrained by computational time and storage space. Hence, the results are often aggregated to a coarser level of granularity—for example, risk may be reported at the portfolio level, by currency, or by product type.

The VaR reports box is an interface (often called a GUI or graphic user interface) which the risk managers use for daily reporting or ad hoc investigations. This function also performs risk decomposition. Finer levels of decomposition depend critically on the system’s ability to perform ad hoc VaR runs on targeted portfolios under investigation.

VaR can be very computationally intensive. As an extreme example, suppose we want to compute hsVaR at the finest possible granularity, and there are 10,000 deals, 10,000 risk factors, 250 scenarios per risk factor (these are very conservative estimates). The system will need to perform full revaluation up to 25 billion times and may take a few days of computation time. If some of the deals require Monte Carlo simulation for their revaluation, the number can be even more staggering. In the fast-paced world of investment banking, any VaR system that takes more than a fraction of a day to calculate will become useless. The risk numbers will be obsolete by the time the VaR report reaches its audience.

In practice, most deals only depend on a very small subset of risk factors (for example a vanilla interest rate swap will only depend on a single currency yield curve), which could be used to considerable advantage through efficient portfolio construction and an intelligent VaR engine design. For example, such a VaR engine will not bother shocking risk factors that the deal/portfolio does not depend on, and thus reduces the time taken for VaR computation.

A less creative solution, given present-day technology, is to judiciously select the granularity level for meaningful risk control and to invest in system hardware. Thus, many banks are resorting to parallel computing to achieve higher computational power.

To understand why risk factor mapping is necessary, we reflect that VaR is a portfolio risk measure. In the Markowitz portfolio theory, risk can be diversified (lowered) when aggregated. The property of subadditivity allows the portfolio total risk to be lower than the sum of risks of individual deals.

Well, we can calculate the risk of each deal (say by looking at its price changes) and sub-add them using the Markowitz framework, but this is inconvenient and unintuitive. Since many products are driven by common risk factors it makes sense to map them to a set of risk factors and sub-add the risk factors instead.

This is natural. Risk managers typically perform risk decomposition (to analyze where the risk is coming from) based on risk factors, not based on deals. Dealing with risk factors is also computationally efficient because the number of deals can grow very large, but the risk factor universe remains relatively fixed.

For example, a trader’s portfolio may contain thousands of FX option deals and FX spot deals for hedging. The risk elements of each deal can be mapped to just a few risk factor classes—FX spot, interest rates, and FX volatility—and they are naturally netted within each risk factor itself. The risk factors can then be sub-added to obtain portfolio risk.

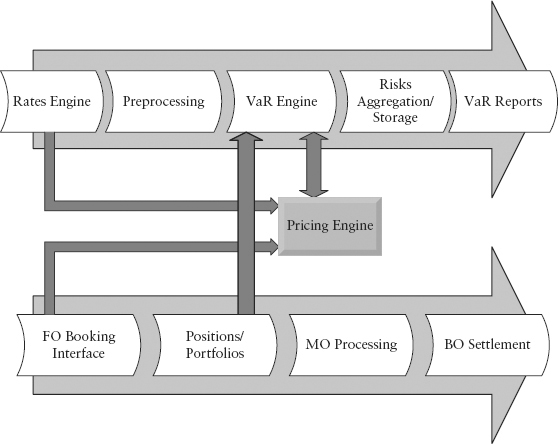

Before we classify the risk factor universe, we need to appreciate that only market risks can be measured by VaR adequately in a truly portfolio diversifiable sense. Market risks are tradable risks that have continuous price quotations. See Table 3.1. Hence, their time series, necessary basic building blocks of VaR, are available.

TABLE 3.1 Types of Market Risks

In contrast, nonmarket risks such as those listed in Table 3.2 are nontradable. Without observed price series, this cannot be aggregated into portfolio VaR (in a fully diversifiable sense). The risk models in this area are still in their infancy, and data are unreliable. There are many attempts to integrate all risks under the VaR umbrella, as seen in advances in enterprise risk management. It is an appealing school of thought but such aggregation is typically done as a simple VaR summation without considering the correlation.

TABLE 3.2 Types of Nonmarket Risks

| Risk Type | Example |

| Nontradable credit risk | Counterparty risk, illiquid loans (credit cards, mortgages), commercial loans |

| Operational risks | Rogue trader, deal errors, security breach, hardware breakdown, workplace hazard |

| Reputation risk (often considered operational risk) | Law suits, fraud, misselling, violation of regulations, money laundering |

| Liquidity risks | Bid/offer cost, market disruption, enterprise funding risk, bank runs |

Sometimes the resulting VaR may not be meaningful. For example, market risk VaR is often expressed with a 10-day horizon for regulatory reporting. Can we really express operational risk over a 10-day horizon? And what does it mean? Evidently, the industry is still far from a fully unified framework for risks. The challenges of unification are discussed in Chapter 10.

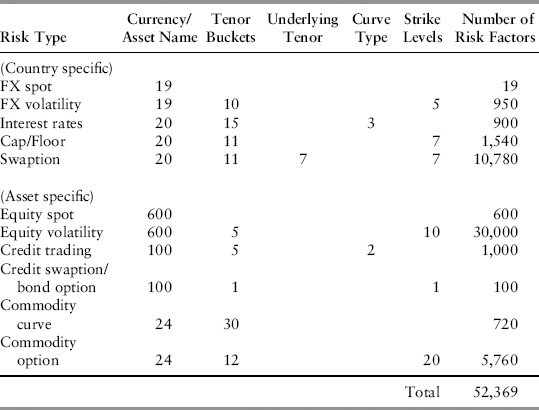

The columns in Table 3.1 refer to the various possible dimensions of risk for a particular asset class. For example, options can be written on any asset class, and that introduces an extra dimension of risk (on top of the common price risk), that of volatility. Likewise, the innovation of credit derivatives in the late 1990s created yet another dimension of risk, that of issuer default. Some asset classes by nature of their cost of carry, exhibit a term structure or yield curve. This means that each point (or pillar) on the yield curve is a single risk factor with its own bid/ask quotation. We consider the term structure a dimension of risk in its own right, because the curve features a unique duration risk. Lastly, the innovation of basket and spread products created a rather abstract dimension of risk to trade, that of correlation.

Crucially, to qualify as bona fide risk factors, the volatility and correlation dimensions have to be implied from market product prices as opposed to that derived from historical prices of the underlying. For example, it is well known that option-implied volatility is often very different from historical volatility. In particular, it can exhibit a volatility smile—where options with strike prices away from at-the-money show progressively higher implied volatilities. Implied volatilities of differing strikes are distinct risk factors.

More subtly, implied correlation too is distinct from historical correlation. One cannot use historical correlation in place of implied correlation, any more than one can use historical volatility as an option’s risk factor. Historical correlation is backward-looking (thus lagging) and provides the general construction for portfolio diversification of any assets; that is, it is already embedded in VaR.

In contrast, implied correlation exists only for exotic products that use correlation as a pricing parameter. Since this parameter is tradable and uncertain, there is (correlation) risk. Implied correlation is forward-looking and often responds instantly to market sentiment. Despite the obvious need, most banks do not include implied correlation risk into their VaR because this risk factor is difficult to handle. There is a wall of challenges in terms of modeling, technology, and data scarcity. This issue is discussed in Section 4.5. Except in that section, implied correlation risk factors will not be considered.

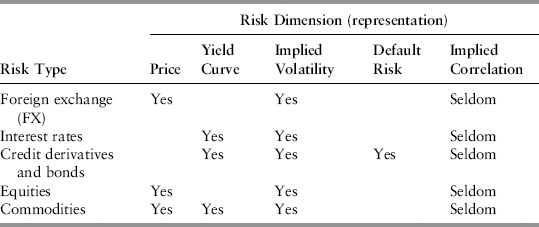

To appreciate the size of the factor universe, let us look at a conservative illustration of the factors used by a typical bank. Table 3.3 shows the count of the number of factors for a combination of risk type and dimension. The last column is the product of each row. The sum of the last column (52,369) gives the size of the risk factor universe. Most banks will have a factor universe twice this size or larger because of finer gradation.

TABLE 3.3 An Example of Risk Factor Universe

Let us briefly explain each risk type. The upper half of the table displays country-specific risk types. For simplicity, we consider only G-20 countries; hence, there are 19 FX spot exchange rates (against the U.S. dollar). Banks typically divide the maturity of deals into standard tenor buckets (or pillars) for risk-mapping, for example: {1d, 1w, 1m, 3m, 6m, 9m, 1y, 2y, 3y, 4y, 5y, 7y, 10y, 15y, 20y}.

If the bank trades in FX options, these can be in any of the 19 currencies. FX options are typically liquid from 1w to 5y maturity, so they fall into 10 tenor buckets. We also bucket the (implied) volatility risk into 5 strike levels (with delta of 10, 25, 50, 75, 90). Thus, the number of possible risk factors for FX options is 19 · 10 · 5 = 950 combinations. The volatility plotted on a tenor vs. strike grid is called the volatility surface.

For interest rate risky assets, we assume the curves for each currency are quoted from 1d to 20y (15 buckets). At its simplest, there will be three types of rate curves—the swap curve, the government curve, and the cross-currency basis curve (against USD). The basis curve is the rate curve implied from prices in the FX forward and currency swap markets. The basis curve reflects the demand-supply for the foreign currency versus the USD. Hence, for interest rate risk, we have 20 · 15 · 3 = 900 risk factors.

Two vanilla (or basic) options for rates derivatives are cap/floor and swaption. They constitute the most liquid instruments available for volatility price discovery. A cap/floor is a basket of options to deliver a forward rate agreement (FRA). A FRA is a forward (or deferred) start loan; for example, a 6x9 FRA is a 3-month loan that starts 6 months from trade date. The typical volatility surface for cap/floor is defined on a grid of 11 tenors versus 7 strikes.

A swaption is an option contract to enter into a swap. Since the option maturity is distinct from the underlying swap maturity, the swaption volatility surface is actually three-dimensional. For example, in the Table 3.3 we have 11 swaption maturities versus 7 swap maturities versus 7 strikes. This is sometimes called the “vol cube.” With 20 vol cubes, one for each currency, the number of risk factors swells to 10,780.

The lower half of Table 3.3 displays risk factors belonging to a specific named asset such as that linked to a company, a debt issuer, or a specific commodity. Since there are many specific tradable assets in the world, the factor universe is even more nebulous, and banks will limit the size of the set sufficient to cover the markets they actually trade in.

In Table 3.3, we simplistically assume the bank trades an average of 30 stocks in each of the 20 countries. Hence, there will be 600 equity names. For stock options, most listed options are quoted from 1m to 1y (five tenors) and have 10 strike levels defined. Thus, we have 30,000 risk factors here.

The vanilla products in credit trading are risky bonds and credit default swaps (CDS). The universe of issuers (or obligors) is large, but there were probably just around 100 liquid names traded before the 2008 crisis. Hence, 100 is a reasonable estimate for a small bank. For risk management purposes, it is important to distinguish between two curve types (for the same issuer)—the CDS curve and the asset swap curve—because of the basis risk between the two.1 The credit curve typically contains five tenors (1y to 5y) although the reliable (liquid) point is really just the five-year. Options on CDS and risky bonds are typically illiquid—the volatility surface is not observable, and most banks will just estimate a single point volatility (five-year, at-the-money strike) as the risk factor.

For commodity factors, we note that the Goldman Sachs commodity index (a popular benchmark) has 24 components. These 24 commodities represent broadly the commodity world. For most commodity futures, there are typically 30 contract months (hence, 30 monthly tenors) in the forward curve. Thus, we estimated 24·30 = 720 factors. As for listed commodity options, they are less liquid than futures and are commonly quoted up to one year (12 monthly tenors) with 20 defined strike levels. Thus, commodity options can contribute a huge number of factors—5760 in this case.

Each element in the risk factor universe has its own time series data that are collected daily. A bank needs to maintain this data set in order to operate its VaR engine.

In VaR applications, each deal may be mapped to multiple risk factors that it is exposed to. For example, assuming the base currency for reporting VaR is USD, a five-year risky bond denominated in EUR is mapped to the following factors: EUR interest rate curve (up to 5y), EUR/USD spot exchange rate, the credit curve of the issuer (up to 5y)—a total of 17 factors from Table 3.3. We will see more examples in Chapter 4.

A proxy risk factor is a surrogate risk factor that is used when data history for the actual held asset is not available. Proxies are often used in emerging markets where the markets are illiquid and data history is sparse. Some asset classes such as corporate bonds and credit derivatives are by nature illiquid. These are issuer-specific securities that at times fall out of popularity with investors. Hence, some parts of their price history may be stale or not updated. Under these circumstances, a suitable proxy is required.

The handling of proxies requires much subjectivity. Under what circumstances should a proxy be considered? What makes a good proxy, and must the proxy be scaled?

If prices for an asset exist but are not well-behaved (bad data), you are better off using a proxy. Remember that in practice we are interested in the portfolio level VaR; that is, how this single additional asset affects the overall VaR. If the bad data series has many erroneous spikes, the portfolio VaR will be overstated. On the other hand, if the bad data series has many stale points, the portfolio VaR will be understated.

The idea that small errors from a single asset may be diversified away in a large portfolio is dangerous. Small, unaccountable errors can build up in a VaR engine over time, and it will be increasingly difficult to explain the drivers of a bank’s VaR. Since early 2008, there has been a policy push by regulators in favor of including issuer-specific or idiosyncratic risk into VaR. Because many of the data series in this space are bad, it is questionable whether the risk manager is including useful information or garbage into his VaR system. The guide to staying on the right path is to always remember that VaR is only as good as the input data. So how good is this particular data?

As an example, consider the data series of Lebanon five-year CDS spread in Figure 3.2 for the period May 2007 to Apr 2008. During half of that time the data set was illiquid and hence stale; therefore a proxy is called for. The logical choice, based on geopolitical similarity will be the five-year Israel CDS spread, which has better data history. On closer inspection, one will be surprised to find the correlation of returns of the nonstale days to be near zero. This seems to be a general observation in the credit trading market and is due to illiquidity (compared to other asset classes). Returns are uncorrelated even for issuers within the same industry and even though the spread levels are themselves correlated. This poses less of a problem for VaR since we are actually interested in correlation in the tail or quantile—as long as large spikes in spreads are in sync between Israel and Lebanon, the VaR will be correlated. Taking only the largest seven and smallest seven scenarios and computing correlation again, we find a correlation of 0.5—a more intuitive result (that supports our choice).

Now, we just cannot replace the Lebanon time series with the Israel time series in the VaR system—their volatilities are vastly different—the standard deviations are 12bp versus 2.8bp respectively. We need to scale up the Israel time series in the system by 4.5 times and rename it Lebanon proxy.

Using proxies introduces basis risk into VaR (addressed in Section 4.6). This is still preferable to leaving bad actual data in the VaR system whose impact it is impossible to quantify. The basis risk between Israel and Lebanon CDS spreads should be conservatively estimated (even if only roughly) and provisioned for using a reserve.2

In Section 3.2 we looked at how a risk factor universe is selected to represent all tradable assets relevant for a bank. Each risk factor comes in the form of a daily time series of level prices (or rates). But VaR uses returns as inputs since it is the quantile of a return distribution of an observation period. Hence, the returns series (or scenarios) need to be generated. In this book, we chose a 250-business day rolling observation period (or window) representing one calendar year. So the return series is represented by a scenario vector (of length 250). The scenarios are indexed 1 to 250; by convention, scenario 1 is the daily return at today’s close-of-business (COB) date, scenario 250 is the return 250 days in the past from COB.

Once we have derived the scenarios, we can use a scenario to shift the current price level (or base level) to the shifted level. Each deal in a portfolio is then revalued at the current level and the shifted level. The difference between the two valuations is the profit and loss (PL) for that scenario. Do this for all 250 scenarios, and we get a PL vector, which is actually a distribution with 250 data points. We shall see in the next chapter that VaR is just the quantile taken on the PL vector.

There are three common ways to generate a return series from a price series:

Absolute:

Relative:

Log:

where i = 1, . . . , 250 is the time index (in reverse chronological order). Here the terms rate and price are used interchangeably.

Absolute return is suitable for interest rate risk factors because it can handle low and negative rates. A daily change from +0.02% to +0.06% (a mere +4bp absolute change) would imply a 200% relative change. In the 2008 crisis, short-term overnight rates were set ultralow by central banks to counter the liquidity crunch. When the market recovers, rates may rise to a much higher base level even though the scenario vector remains largely unchanged. Thus, by equation (3.4) the PL vector (and hence VaR) will be overstated.

Sometimes rates can go negative momentarily. A change from −0.05% to −0.04% (+1bp rise) is reflected as a 20% fall by equation (3.3). Hence, relative return gives the wrong sign when rates are negative.

For all other risk factors (that never go to low/negative prices) relative or log return is preferred because it takes into account the base level. For example, a gain of +$1 from $1 to $2 is a lot riskier (100% increase) compared to that of $100 to $101 (a 1% increase).

Negative rates do occur for nondeliverable forwards (NDF). For some semiconvertible currencies, government restrictions create a dislocation that makes arbitrage difficult between onshore and offshore forward markets. Without a corrective mechanism, the implied forward rates of offshore NDF can go negative momentarily.

These negative implied rates are not fictitious—they do give rise to real mark-to-market (MTM) PL should the position be liquidated. Nevertheless, for the purpose of VaR, there are a few good reasons why we should floor these rates at a small positive number (say at +0.05%). Firstly, the rate normally goes negative for very short periods and is corrected in a matter of days. Secondly, the negative rates typically happen at the very short end of the curve (say less than one-week tenor) where the duration risk is tiny. Thirdly, even though vanilla product pricing can admit negative rates, many pricing models for complex products cannot. Since most banks run exotic books hedged with vanilla products, the overall risk of the portfolio can be misrepresented if negative rates are permitted.

More generally, certain quantities should not admit negative values in order to satisfy the so-called nonarbitrageable condition. These are interest rates, forward interest rates, option volatilities, and probability of defaults (as implied from default swaps). Since VaR uses historical scenarios, if the current level of a risk factor is slightly above zero and a historical scenario happens to be a large fall, it is possible for that scenario to produce a negative state. Such a scenario is unfeasible because should it happen, arbitragers would be able to make a riskless profit from the situation. Banks usually have methodologies to correct such undesirable scenarios in their VaR system. These technicalities are beyond the scope of this book.

Simplistically VaR is just the loss quantile of the PL distribution over the chosen observation period. In the industry, different banks use different specifications for their VaR system. Often a firm-wide VaR number is reported to the public or the regulator. In order to attribute any meaning to the understanding or comparison of VaR numbers, it is important to first specify the VaR system. A succinct way to do this is to use the format in Table 3.4.

TABLE 3.4 VaR System Specification Format

| Item | Possible Choice |

| Valuation method | Linear approximation, full revaluation, delta-gamma approx. |

| Weighting | Equal weight/exponential weight in volatility/correlation |

| VaR model | Parametric, historical simulation, Monte Carlo |

| Observation period | 250 days, 500 days, 1,000 days |

| Confidence level | 95%, 97.5%, 99% |

| Return definition3 | Relative, absolute, log |

| Return period | Daily, weekly |

| Mean adjustment | Yes/no |

| Scaling (if any) | Scaled to 10 days, scaled to 99% confidence level |

As a prelude, let’s describe a reasonable VaR system specification, which is workable in my opinion and which we shall use as a base case throughout the book. See Table 3.5.

TABLE 3.5 VaR System Specification Example

| Item | Selection |

| Valuation method | Full revaluation |

| Weighting | Equal weight |

| VaR model | Historical simulation |

| Observation period | 250 days |

| Confidence level | 97.5% |

| Return definition | Log return |

| Return period | Daily |

| Mean adjustment | Yes |

| Scaling (if any) | Scaled to 10-day holding period and 99% confidence level |

The advantages of a full revaluation and historical simulation model will be covered in Chapter 4. A rolling window of 250 days (one-year) is short enough to be sensitive to recent changes (innovation)4 in the market. Had we chosen a 1,000-day (four-year) window, the VaR will hardly move even when faced with a regime change. This is undesirable.

At 97.5% confidence, the number of exceedences in the left tail is six to seven data points. At higher confidence (say 99%), the number of exceedences becomes too few to be statistically meaningful (two to three points). And at lower confidence, the quantile may not be representative of tail risk; we may be measuring peacetime returns instead.

Log returns with flooring of rates (no negative rates allowed) have the advantages mentioned in Section 3.4. Daily data is used because it is the most granular information5 and will be more responsive than, say, weekly data. The specified scaling is a regulatory requirement. For the bank’s internal risk monitoring, the scaling is often omitted.

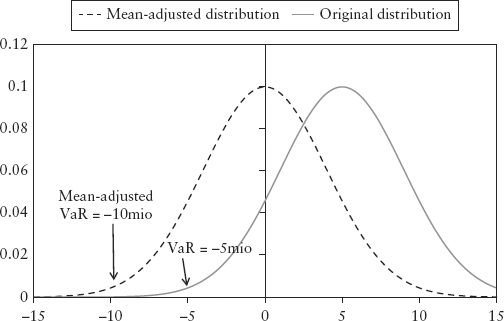

Mean adjustment is the process of deducting the average of the PL vector from the VaR quantile. Then, the PL distribution, which may be skewed to one side, becomes centered (see Figure 3.3). Some banks report VaR based on a mean-adjusted basis; others don’t. This book adopts the former approach.

FIGURE 3.3 Mean Adjustment Applied to PL Distribution

Mean adjustment is necessary to make the VaR measure consistent. Let’s see why.

When implementing mean adjustment, it is important to deduct the mean at the level of the dollar PL vector, not at the return scenario vector. In practice, this means the adjustment is done after product revaluation. For linear products it doesn’t matter—mean adjustment done at the scenario vector (return distribution) or done at the PL vector (PL distribution), produces the same VaR. However, in the presence of options, they are generally unequal.

To see why it matters for options, suppose the underlying stock has a return distribution with a mean (say −0.1%) skewed very slightly to the left. If the portfolio contains call options, the portfolio’s PL distribution (after revaluation) can be skewed to the right (say with mean +0.5%) as a result of the loss protection provided by the options. So we mean-adjust the PL distribution to the left. But had we performed mean adjustment in the return distribution instead, we would have mistakenly adjusted to the right resulting in a very different VaR outcome.

For the sake of simplicity, in this book, we will often mean-adjust the return distribution unless the example involves an actual dollar PL distribution.

1. The basis exists because of structural and liquidity differences between the two products. The asset swap curve is derived from risky bond yields, whereas CDS spreads are like an insurance premium on that issuer. CDS are traded in a separate and often more liquid market.

2. A provision or a reserve is money set aside to cushion against any risks that are not well captured or understood. In this case it is the risk of “not knowing the difference in risk between the two risk factors.”

3. Different return definitions may be more suitable for different risk factors. Hence a real-world VaR system may contain a mixture of return definitions.

4. New changes in market prices (or incoming data) are occasionally called innovation in academia.

5. Intraday data is seldom considered because price gaps that occur during opening and session breaks often make the data nonstationary.