The recognition of major risk classes by the Basel Committee for inclusion into the regulatory capital regime has been the driving force for the development of their risk models. The original Basel I Accord (1988) focused on credit risk, which is by far the largest risk class faced by banks. An Amendment (1996) included market risk into the capital regime and introduced the “internal models” approach (by de facto value at risk, or VaR). The Basel II reform (2004) established operational risk as a major risk, following the fall of Enron and WorldCom, two of the largest corporate bankruptcies caused by unauthorized trading and accounting scandal. The 2008 credit crisis highlighted two other risk classes that were overlooked—firm’s liquidity risk and counterparty credit risk. These are addressed in Basel 2.5 rules (in 2009), which were subsequently subsumed into Basel III (in 2010). This chapter gives a brief overview of risk classes (other than market risk) and the conventional models used to quantify them before Basel III. In the next chapter, we look at the new models of Basel III.

From a regulatory capital perspective, one challenge is in aggregating these diverse classes of risk—credit, market, operational, counterparty, and liquidity. This so-called problem of aggregation to merge the various risks under a unified theory has attracted much interest from academics. The last section addresses the challenges of aggregating these very different items.

Credit risk refers to the risk of default and risk of ratings downgrade of companies. Such events are company (or name or issuer) specific and often happen when the creditworthiness (credibility to raise funds) of a company is fundamentally impaired or is perceived by the market to have deteriorated.

Since banks and investors often hold exposures to companies, they are exposed to credit risk. Such exposures come in various forms. If the exposure is in the form of a (nontradable) loan to a company, then this is technically a banking book credit risk. If the exposure is in bonds or securities issued by that company, or credit derivatives written on that company, then this credit risk is a component of trading book1 market risk. If the exposure exists because the bank traded with that company and funds are owed, then it is considered a counterparty risk. Such distinctions are inconvenient but necessary because the nature of data, modeling method, accounting rules, and regulatory capital treatment are all very different.

In this section, we will look at the modeling of credit risk of loans and traded instruments using CreditMetrics developed by J.P. Morgan in 1997. There are a few other popular models available; see Crouhy and colleagues (2000) for a comparative analysis.

CreditMetrics asks: “Over a one-year horizon, how much value will a loan portfolio lose within a given confidence level (say 5%) due to credit risk?” The answer, expressed as credit VaR, will incorporate both risk of default and rating downgrades. Our example uses simple Monte Carlo simulation and will illustrate all the key ingredients of CreditMetrics. It helps to divide the calculation process into three steps.

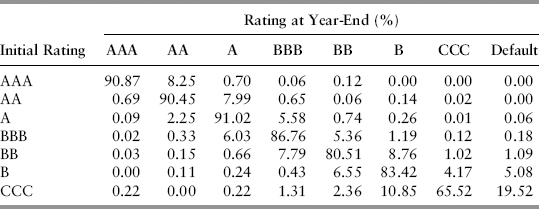

A bond issuer’s creditworthiness is often rated by credit rating agencies such as Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s. For loans, banks typically use internal credit scores. To measure the risk of deterioration in credit quality, we need the probabilities of migrating from the initial state to another rating level. This information is contained in the transition matrix published regularly by rating agencies. Table 10.1 is an example. The numbers reflect the average annual transition probability from initial state to final state one year later. These statistics are compiled based on actual observations of firm defaults bucketed by specific industry sectors and ratings over a long history (i.e., there will be one matrix per industry sector).

TABLE 10.1 One-Year Transition Matrix (%) (numbers below are hypothetical)

While the rating transition matrix has been generally accepted by the industry for risk modeling, it is often criticized for being backward-looking. Observations of actual bankruptcies occur very slowly and will not capture the shift in market expectations of a credit deterioration of a company (expectation is forward-looking). Hence, some banks attempt to model the transition probabilities as a function of credit spreads and macroeconomic variables that are more contemporaneous.

The loan portfolio will need to be revalued using the 1-year forward credit spread curve. For simplicity, we consider the case of a simple bond with fixed annual coupon, c. The value of the bond in one year including the next paid coupon (first term) is:

where there are n coupons left after one year, si is the forward spread,2 and fi is the forward risk-free discount rate, which can be derived from today’s discount curve3 ri from the simple compounding relation:

where i = 1, . . . , n, time ti is expressed in fractional years and (ti+1 − ti) is the coupon period. Since we can observe from the market a unique spread curve si for every rating in the matrix, we can compute the value for each bond in the portfolio for all the seven ratings using (10.1). The defaulted state’s value is simply given by the recovery rate4 multiplied by the forward bond value.

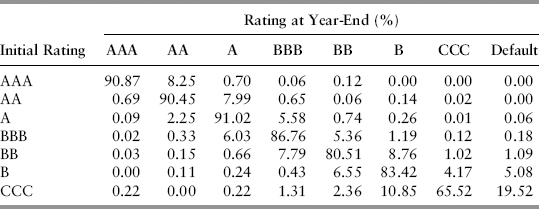

Spreadsheet 10.1 is a toy implementation of CreditMetrics for a portfolio of three bonds. In order not to digress from the main presentation, we will not show the valuation of the bonds as per equation (10.1), but simply state the results in Table 10.2. This table will be used subsequently to look up the bond values at each simulated credit rating end state.

TABLE 10.2 Bond Values of Different End States at the One-Year Horizon ($/million)

Credit migrations of different companies are expected to show positive correlation because companies tend to be influenced by common macroeconomic drivers and the business cycle. But how can we measure a default correlation, which cannot be observed?

The solution is to consider Merton’s model (1974), which sees the equity position of the borrowing firm similar to holding a call option on the assets of that firm. The idea is that because of limited liability, equity holders can never lose more than their original stake. Company default is then modeled as the fall in asset prices below the firm’s debt (i.e., the option “strike”). Thus, default correlation can be modeled by the correlation of asset returns, which in turn can be measured as the correlation of readily observed equity returns.

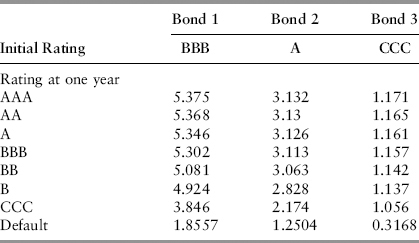

Once the correlation matrix is derived using equity returns, it needs to undergo Cholesky decomposition before it can be used to simulate correlated random asset returns. The asset returns are assumed to follow a normal distribution. A common misconception is that by assuming normal distribution, we are somehow not capturing the well-known fat-tail effects in credit spread changes. This is not the case, however, because we are assuming normality for the (stochastic) drivers of credit changes, not the credit changes themselves. In fact, as will be seen later, the final portfolio distribution (Figure 10.2) is heavily fat-tailed.

FIGURE 10.2 Portfolio Distribution and Credit VaR

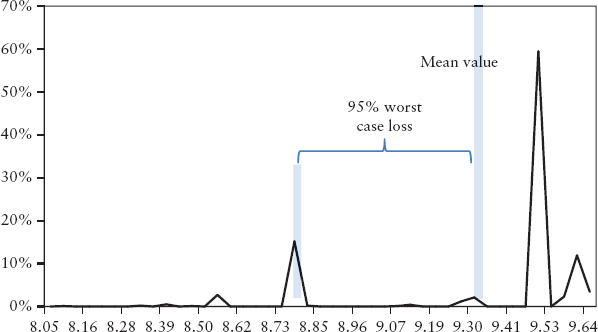

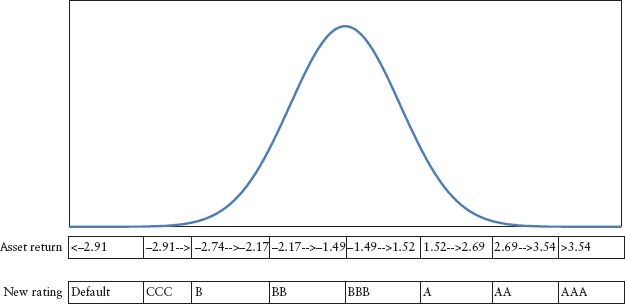

To translate a random draw from the multivariate normal distribution to an asset value in the end state, we need a mapping table. This is created by partitioning the scale of end ratings according to the normal distribution scale by matching the transition probability. See Figure 10.1.

FIGURE 10.1 Partition of Asset Change Distribution for BBB Issuer (Bond 1)

To obtain the portfolio distribution, Monte Carlo simulation is employed to generate three correlated random variables (one for each bond) for a large number of scenarios. Based on the drawn asset returns, we can read from the partition the corresponding end states of the bond’s rating. And, based on the end states, we can read off Table 10.2 the final dollar value of the bond at the horizon. The three bond values are added per scenario to give the final portfolio distribution.

Credit VaR is then defined as the loss quantile of this distribution at a given confidence level. Figure 10.2 shows that the 95% worst case loss from the mean is $0.6 million. See Spreadsheet 10.1 for a worked-out example.

Note that traditional credit portfolio models such as Creditmetrics are now superseded by more sophisticated Basel III models such as the IRC (see Chapter 11).

Liquidity risk has long been identified as a key risk in financial assets. To quantify it, it helps to first define what liquidity risk is. The common term liquidity risk is loosely defined and could mean a few things:

Consider the first in the list. In banks, the management of day-to-day liquidity is run by the asset & liability management (ALM) traders and risk controllers. The subprime crisis in 2008 has witnessed how the sudden appearance of funding liquidity risk almost caused the complete collapse of the world financial system. The fear of counterparty default had made banks reluctant to lend money to each other, which resulted in the hoarding of liquidity. The global payment system choked as liquidity dried up. After the credit crisis, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) tightened regulations by requiring a liquidity coverage ratio, which stipulated the minimum liquid assets banks must hold to cover a stressful period of 30 consecutive days. This is discussed in Section 11.4.

The last three risks in the list are collectively known as market liquidity risk. MTM uncertainty is a risk that gained notoriety during the credit crisis and is caused by the “insidious growth of complexity”—unchecked product innovation driven by the speculative needs of investors. As such products are over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives—bespoke and illiquid—their risk is difficult to regulate and is stealthy in nature. No single regulator monitors the total outstanding notional globally or the identity of the counterparties holding such derivatives.

For example, the models used to price credit default obligations (CDOs) broke down during the 2008 crisis and led to a loss of confidence in using such models (price quotes disappeared), even though trillions of dollars of such derivatives had already been issued. With complex products, MTM uncertainty is intricately linked to model risk. By the definition in Section 9.3, model risk is the difference in theoretical and observed traded prices. During the CDO debacle, both were indeterminate and indeed this eventually led to the setup of the Troubled Asset Repurchase Program (TARP) by the United States government. The TARP was tasked with disposing of these toxic products over time in an orderly fashion in order to reduce further fallout to the financial markets.

In recent years, there has been development in incorporating market liquidity risk into the VaR framework. For a review of such models please refer to Sebastian and Christoph (2009). Generally, the models attempt to include the bid-ask costs into the VaR distribution (or return scenarios).

In the more advanced models, the bid-ask cost is weighted by transaction volumes using data from exchanges. Such models not only consider the bid-ask cost but also the depth of the limit order book. As an example, suppose the bank has q = 1,000 lots of shares of a company. The liquidity cost may be given by:

where a(q) is the average ask price weighted by transaction volumes as a trader sweeps the limit orders on the offer side in the limit order book, to fill 1,000 lots. Likewise, b(q) is similarly defined on the bid side. Since most banks mark their position at mid price xmid, the multiplier of 0.5 reflects that only half of the round trip transaction cost is incurred. This percentage liquidity cost is converted into continuous terms by: l(q) = ln(1 − L(q)). Then, the asset’s return net of liquidity cost is given by:

where rt is the asset return on day t. To calculate the liquidity-adjusted VaR (L-VaR), we use rnet(q)t in place of rt for scenario deal repricing and taking of the quantile. Equation (10.4) essentially widens both sides of the return distribution by an amount given by the liquidity cost as observed on individual past dates.

L-VaR rests on two unrealistic assumptions. Firstly, it assumes past liquidity cost (of the last 250-day observation period) is a good predictor of future liquidity cost (in the next 10-day horizon). This is difficult to justify if we reflect that the credit default swaps (CDS) bid-ask cost prior to 2007 would have understated liquidity costs during the credit crisis in 2008, and the bid-ask cost in 2008 would have overestimated liquidity costs since the crisis.

Secondly, L-VaR assumes the entire bank’s positions were unwound everyday in the past observation period. Clearly a bank will only liquidate entire holdings when it is in credit difficulties. The probability of such a mass liquidation event is small and is not accounted for in L-VaR, leading to possible overstatement of risks.

In this section we propose a simple add-on that can be used for reserve purposes. First, we attempt to include slippage in the bid-ask spreads by defining the adjusted spread as:

where qn is the bank’s net notional holdings of asset n. For an asset n, dn is its bid-ask spread, Nn is the quoted maximum size that can be traded in a single transaction without moving the bid-ask quote. Equation (10.5) mimics the “sweeping” of a limit order book. For example, if Nn is 200 lots, and a bank needs to liquidate immediately q = 1,000 lots, the transaction will consummate five levels of bid-ask spreads in the order book, assuming the limit orders are homogenously queued. The second term reflects that a bank only crosses half the bid-ask spread at the first level.

The latest Nn and dn can be subjectively observed from over-the-counter (OTC) markets, or automatically collected for exchange-traded products. For illiquid and bespoke products, a bank can use the spreads it quotes to a typical client. A bank would have a good idea how much transactional cost it wants to charge a client based on traders’ assessment of the complexity, liquidity, and hedging costs of the product.

When “crossing the bid-ask” we can assume linearity in pricing even for option-related products because the difference in price levels between bid and ask is relatively small. A sensitivity approach is thus valid:

where j is the number of assets, and pn a probability factor (explained in the next section). We include only the primary risk factor’s bid-ask spread for each asset n. This recognizes the way products are traded between professional counterparties—the bid-ask of only one primary risk factor is crossed. For example, the risk factors for an FX option are spot, interest rates, and volatility, but actual trading is quoted in volatility terms; hence the volatility bid-ask is the only cost. The relevant sensitivity is vega in this case.

Equation (10.6) is calculated and summed across all j assets without any offsets. Since liquidity cost cannot be diversified away, netting between long and short is not allowed, except for instruments that are strictly identical in risks. Another exception should be made for non-credit-risky cash-flow products because cash flows of two such deals are considered fungible.5 One way is to bucket such cash flows into time pillars (with offsets) and then treat each pillar as a separate asset for the purpose of equation (10.6).

The pn in equation (10.6) accounts for the probability of a mass liquidation event. A rough estimate is the probability of default for the bank or its interbank counterparty (for asset n), as implied by their CDS spreads. After all, it is reasonable to assume that when a bank fails, it has to liquidate its holdings, or when its counterparty fails, the bank has to hedge outstanding positions.

As regulators use a 10-day horizon for safety capital, it makes sense to use a 10-day default probability derived from a 10-day CDS spread. (If this is not readily observed, the benchmark 5-year CDS spread can be used.) The marginal default rate is related to CDS spread by:

where s is the larger of the bank’s own CDS spread and the counterparty’s CDS spread. Δt = 10/250 and R = 0.45, an assumed average default recovery rate for the banking sector.

To get a sense of magnitude of the add-on using this simple model, consider a credit derivative position of just one issuer with a notional of $500 million and maturity of 5 years. The add-on calculation is shown in Table 10.3.

TABLE 10.3 Calculation of Market Liquidity Risk Add-On for $500 Million Position

| Exposure to a Single Credit Derivative Issuer | |

| Holdings of 5-year CDS | $ 500,000,000 |

| Bid-offer spread (BP) | 5.00 |

| Maximum liquid size | $ 20,000,000 |

| Adjusted bid-ask spread | 122.50 |

| Credit sensitivity per BP | $ 250,000 |

| Bid-offer loss | $ 15,312,500 |

| Calculation of Default Probability | |

| Own CDS spread (BP) | 200 |

| Counterparty CDS spread (BP) | 300 |

| Recovery rate | 0.45 |

| Horizon (year) | 0.04 |

| 10-day default probability | 0.2179% |

| Expected liquidity loss | $ 33,373 |

The add-on may seem small for a $500 million position, but since netting or diversification is not permitted (in general), these costs will add up very quickly on a firmwide basis as the portfolio size grows.

Operational risk modeling is still in its infancy. There is no consensus on the definition of operational risk yet. Some banks broadly define this as risks other than credit and market risks—clearly not a very useful definition. Others define operational risk by identifying what it includes—as risk arising from human error, fraud, process failure, technological breakdown, and external factors (such as lawsuits, fire hazards, natural disaster, customer dissatisfaction, loss of reputation, etc.). With such a broad definition, risk identification and classification (also called taxonomy) is an enormous challenge. Compounding the problem is the general lack of statistical data for all these individual items. Banks normally make do with a combination of in-house data and external data provided by vendor firms.

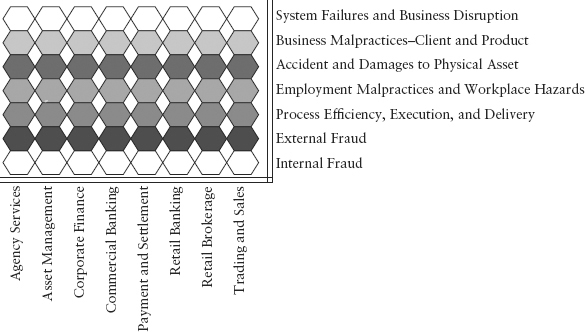

Fortunately, the Basel Committee provided some guidelines. For the purpose of compiling statistics—frequency and severity of losses—identified items should be bucketed into a grid similar to Figure 10.3. The grid represents various combinations of business line (BL) and event type (ET). Ideally the grid must be comprehensive, and each cell should not contain overlapping risk types.

FIGURE 10.3 Operational Risk Factor Grid

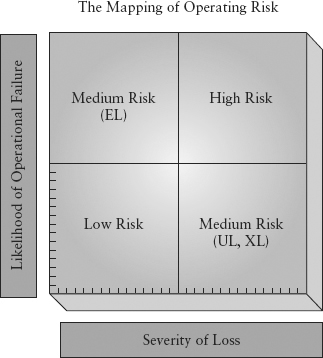

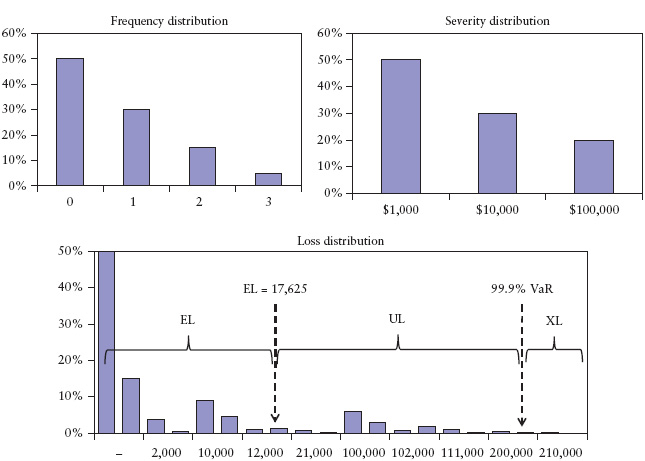

Of course, not all items need to be modeled. It really depends on materiality. Consider Figure 10.4, which shows a zonal map of operational risk. Clearly, resources should not be spent on items that are of low likelihood and low severity (for example, staff being late for work). On the other extreme, an event that occurs very frequently and of high severity represents an anomaly that should be investigated immediately, not modeled (for example, a bank experiencing 10 robberies in a single year). Hence, the focus for quantitative modeling is the zones marked “expected loss” and “unexpected loss/exceptional loss.” Expected loss (EL) is the loss due to process failures, unexpected loss (UL) is typically due to internal control weakness, and exceptional loss (XL) is often a Black Swan event. This division is shown in the loss distribution (Figure 10.5 lower panel).

FIGURE 10.4 The Zonal Map of Operational Risks

FIGURE 10.5 Operational Risk Loss Distribution

A popular way to model operational risk (if data is available) is by using an actuarial approach. The result can be expressed in terms of loss quantile consistent with VaR used for market risk and credit risk. This loss number is called operational risk VaR or OpVaR. Each cell of the grid in Figure 10.3 is assumed to be a standalone risk factor independent of others. Thus, the OpVaRs for each risk factor are simply summed without considering correlation.

For a particular risk factor, historical data on loss are collected for observed events. These are used to model the frequency distribution f(n) and severity distribution g(x|n = 1) where x is the loss for the event, n is the number of events per annum. Hence, g(x|n = 1) is the loss density function conditional on a single event (i.e., loss per event). These are shown in the upper two charts in Figure 10.5. Since OpVaR is normally measured at a one year horizon, the density f(n) is the probability of n events per annum.

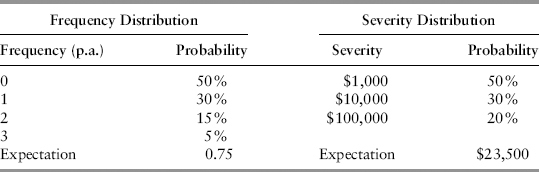

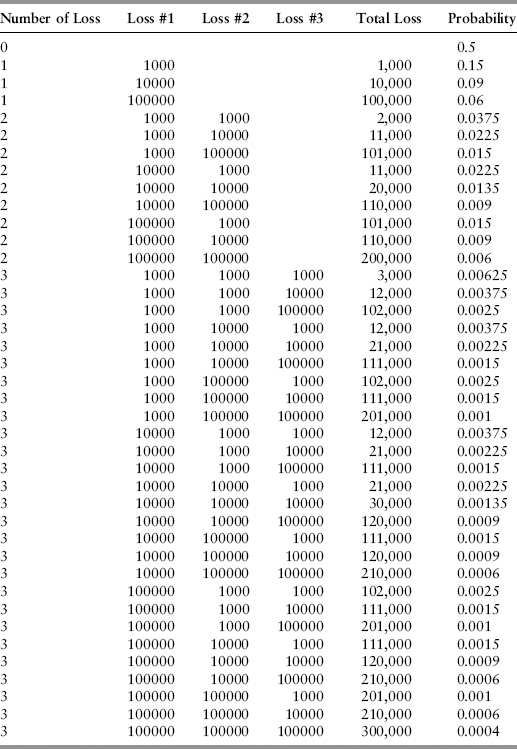

We then use a process called convolution to combine f(n) and g(x|n = 1) to derive a loss distribution. Simplistically, this can be done by tabulation; that is, systematically recording all possible permutations of severity for every n. Table 10.4 shows an example of frequency and severity distributions. Table 10.5 illustrates the tabulation process used to derive the loss distribution. For example, for n = 2, there are nine ways to obtain two events given three possible severity values. For each permutation, the total loss is just the sum of losses for those two events. The probabilities can simply be read off Table 10.4. For example, for the sixth row, the joint probability of n = 2, loss of 1,000 and loss of 10,000 is 0.15 * 0.5 * 0.3 = 0.0225. Spreadsheet 10.2 provides a worked-out example.

TABLE 10.4 Frequency and Severity Distributions

TABLE 10.5 Tabulation of Loss Distribution

The expected loss (EL) is given by the product of the expectation of the frequency distribution and the expectation of the severity distribution; 0.75 * 23500 = 17625. It can also be calculated from Table 10.5 by taking the product of total loss and probability, and then summing the products across all permutations. The plot of the total loss vs. probability is the loss distribution shown in Figure 10.5 (note that the horizontal axis is not scaled uniformly). It is clearly fat-tailed. The 99.9% OpVaR is then defined by the loss quantile at the tail. We consider the region beyond OpVaR as representing exceptional loss (XL). The region between EL and XL gives the unexpected loss (UL). From the diagram, OpVaR = EL+UL.

Under Basel II’s loss distribution approach (an “internal model” approach), the operational risk capital for banks is a function of the sum of OpVaR for all combinations of business line versus event type (BL-ET). The OpVaR is defined on a 99.9% quantile over a one-year horizon. OpVaR is used for regulatory capital. For a discussion about the challenges of OpVaR, see Coleman (2010).

Many experts believe that OpVaR cannot be modeled meaningfully because of scarcity of data and is just a tick in the box exercise to satisfy regulatory requirements.

In the absence of an effective model, the subjective judgment of a vigilant risk manager is paramount. For example, operational risk events tend to happen in a sequence (correlated)—the Enron and Worldcom scandals happened around the same time; likewise more recently in 2012, the Libor fixing scandal, a United Kingdom bank’s money laundering involving Mexican drug lords, and another United Kingdom bank’s alleged dealings with Iran (a country under U.S. sanction). This is no coincidence—a scandal will lead to increased scrutiny from regulators, which leads to uncovering of more scandals. The size of losses from legal settlements and fines is huge. A vigilant risk manager who monitored events closely, would have notched up the operational risk capital by a loss amount guessed from similar recent events.

As directed by Basel, capital charges for various risk classes are calculated separately—some based on internal models (as for market risk) and others on a set of rules given by regulators (as for credit risk). To compute the total charge, the regulator’s current treatment is to just sum them up. This is nothing more than a recipe to obtain the aggregated final charge—there is little conceptual justification. This method suffers from at least three drawbacks, which we will examine closely: (1) It ignores the possibility of risk diversification or offsets; (2) under certain situations the aggregated risk can actually be less conservative; and (3) the final number is difficult to interpret.

Firstly, one can argue that diversification is the hallmark of a good risk measure, without which a risk model tells us an incomplete story. For example, while diversification is not captured in operational risk VaR, we intuitively know its necessity. Why do banks normally fly their top executives to overseas functions on separate flights? The bosses know intuitively to diversify this operational risk (accident hazard). Likewise, a bank that relies on multiple sources of funding has diversified its firm liquidity risk as compared to a bank that relies solely on wholesale borrowing. Yet presently there is no standard approach for modeling firm liquidity risk, let alone its diversification effect.

It is important to realize that the simple summation method implicitly assumes a correlation of one, which is more conservative than the assumption of zero correlation. In other words, “no correlation” does not equate zero correlation. Clearly, when ρ = 0,

Empirical analysis, say by comparing market risk and credit risk time series, would suggest that zero correlation is often a more realistic (and hence preferred) assumption than perfect correlation.

Secondly, the popular wisdom that the simple summation rule is conservative (thanks to equation (10.8)) does not hold true in some situations, especially if we are not clear what exactly we are adding. Breuer and colleagues (2008) showed that simply adding market risk and credit risk may result in a less conservative aggregate in some cases.

A good example6 is foreign currency loans. Consider a foreign bank lending U.S. dollars to a local borrower. The loan contains market risk (FX risk) and credit risk (default risk of the borrower). The two risks are measured separately. In a scenario where the domestic economy slows and the local currency depreciates, from the bank’s perspective, the loan appreciates in value and the credit risk of the borrower increases—the two effects should somewhat offset at first sight. But this diversification argument neglects the fact that the ability of local borrowers to repay depends in a nonlinear way on currency fluctuations. Unless the borrower has other revenues in U.S. dollars, it may be pressed to default on the loan if the currency loss is unbearable. This is what happened to many local borrowers during the Asian financial crisis in 1997. Such trades where credit risk and market risk amplify each other are known as wrong-way trades.

More generally, under Basel, the capital charge for credit and market risk is required to be modeled separately and then simply summed up. However, most products contain both risks, which cannot be decoupled easily because of the complex interaction between credit and market risk. It is unclear whether the diversification benefits are positive or negative. As in the example of a foreign currency loan, its risk may be higher than the simple summation of credit and market risks that exist separately.

Finally, if we add the risk up without a unifying conceptual framework, the aggregated VaR will have little meaning. What does it really mean to add a 10-day 99% market VaR to a one-year 99.9% OpVaR? Also a 99.9% confidence level is incomprehensible and not empirically verifiable. It is impossible to make intelligent decisions if one cannot interpret what the risk numbers really mean.

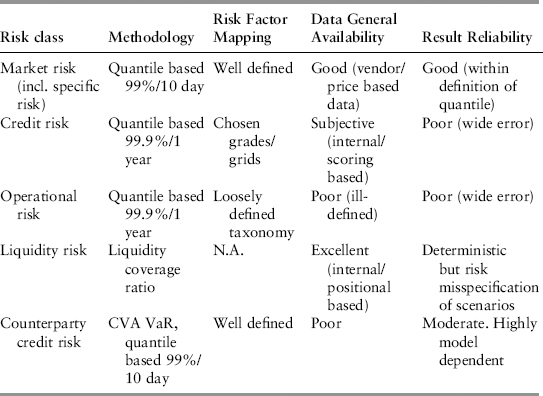

The problem of aggregating these diverse risk classes is a difficult one; they are very different in almost all aspects. Table 10.6 summarizes their characteristic differences.

TABLE 10.6 Summary of Characteristics of Major Risk Classes

In the list, only market risk has enough quality data to be analyzed precisely using a statistical distribution. Even here, problems in the tail can undermine accuracy. Credit and operational risks are known to be fat-tailed and very likely extremistan in nature. On the other hand, liquidity risk will be handled using coverage ratios (see Section 11.4), an appropriate choice of solution and not really a model. It is a good example, which shows that we need not model risk precisely to protect against it. Can this be aggregated?

The unavoidable part about forecasting probabilities of future events is that one needs to specify a horizon. For example, Basel’s market VaR is a forecast for 10 days ahead. If different risks are estimated at different horizons, simply adding them up can lead to undesirable side effects.

As an illustration, suppose there is a casino that offers a game that has a 60% chance of winning for the customer. The casino has a bad fire safety record—it was burned down twice in the last four years. So the hazard rate measured at the 1-year forecast horizon is 0.5 fires per year. Would you play the game (assuming you can bet on-line so there is no personal safety concern)? Are the odds of winning simply 30% (= 0.6 * 0.5) or 60% (= 0.6(1−0.5/365))? The situation is not unlike that of a credit-risky bond where there is a stochastic price risk and a default risk element. There are two lessons here: (1) In order to have a meaningful interpretation, the risks need to be scaled to the same “unit” before adding, and (2) the risk changes with forecast horizon (i.e., frequency of visits to the casino). If you visit just once, the odds are 60%, but if you gamble the whole year round, the odds are 30%.

Scaling the risk from one horizon to another is not straightforward. Firstly, volatility scales with the square-root of time, whereas, default probability scales linearly with time. This implies that the choice of measurement horizon will have an impact on the relative importance of these two risks. Secondly, the popular scaling method is laden with naïve assumptions that are often taken for granted. For example, the square-root of time scaling that is commonly used to bring a one-day VaR to 10-day assumes that returns are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.), normally distributed (see Section 6.4), and that positions remain unchanged in the interim 10 days. These assumptions do not reflect the real trading environment.

The general problem of aggregation can be addressed using the following logic: first scale all risk numbers to the same “units” (i.e., same quantile and same horizon) before adding them up. Are there any diversification effects and complex relationships that need to be accounted for in the summation? If so, is it material? Scaling often requires unrealistic assumptions. Is the error due to these assumptions material at a portfolio level? If the error is unacceptable, to avoid making such assumptions one really has to model the various risk classes within a coherent framework. For a realistic example of a model used by a bank, see the paper by Brockmann and Kalkbrener (2010).

1. See Section 11.1 for the difference between banking book and trading book.

2. The spread curve for a particular issuer is a market observable. For simplicity, we assume a static curve; that is, Si observed at the one-year horizon gives the same values as Si observed today.

3. In practice, the observed curve is the swap curve, which is then bootstrapped to obtain the zero coupon curve or discount curve.

4. The recovery rates depend on bond rating and seniority. Normally they are internally estimated by the bank. Typical values range from 20% to 40% of par.

5. For example, in swaps, when credit riskiness is deemed absent (due to a netting agreement between professional counterparties), one cash flow is no different from another if they fall on the same date.

6. The example is taken from BIS Working Paper No. 16 “Findings on the Interaction of Market and Credit Risk” (May 2009), which discusses the latest progress in unifying market and credit risks.