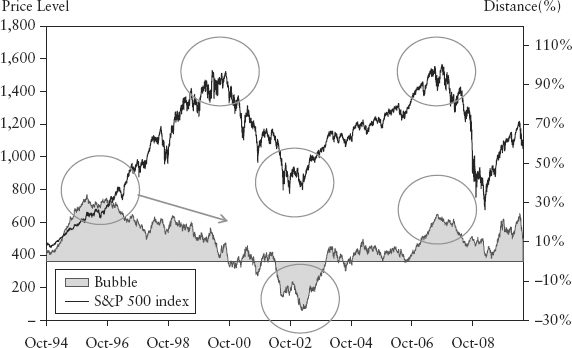

FIGURE 15.1 Bubble Measure for S&P 500 Index

The VaR models used in banks usually undergo the strict statistical tests found in Chapter 8. These goodness of model tests are a regulatory requirement. Passing all these tests proves that a bank’s value at risk (VaR) distribution is independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) and hence the quantile estimate is not biased or understated. Under these peacetime conditions, the VaR model is a consistent metric. The great irony is that a risk manager should be more concerned about extreme conditions, which threaten the bank’s survival. But these are the exact conditions under which such statistical tests would fail.

Unsurprisingly, buVaR will fail these tests even under benign conditions since, by design, this metric is non-i.i.d. (its day-to-day distribution is conditional on the cycle). For example, one can apply standard statistical tests on the (inflated) buVaR return time series and show that it is not i.i.d. Without the convenience of i.i.d., we will need to rely on other less consistent (and less precise) tests. We will test the effectiveness of buVaR by assessing its historical performance covering major financial assets and indices, over a long history and over specific stressful episodes.

Our test is similar to the way a trader would test a trading system—it is subjective, performance-based, and not based on strict hypothesis testing. First, and perhaps most importantly, we check visually to ensure that buVaR is generally doing what it is designed to perform. In particular, we look for evidence of:

The test coverage as shown in Table 15.1 is chosen to broadly represent global financial markets. The buVaR is then computed with parameters as described in Chapter 13. Refer to Spreadsheet 13.4 for a worked-out example. The bubble measure and the resulting buVaR are plotted for analysis. We also chart the expected tail loss (ETL) as a base case for comparison.

TABLE 15.1 Assets Chosen for Visual Checks

| Asset | Asset Class | Benchmark Representation |

| S&P 500 Index | Equity (U.S.) | Global equity market driver |

| Nasdaq 100 Index | Equity (U.S.) | Technology sector |

| Nikkei 225 Index | Equity (Japan) | Asia equity |

| Hang Seng Index | Equity (HK) | Greater China |

| USD/JPY | Forex | Major currency |

| AUD/SGD | Forex | A popular cross currency |

| USD 10-year swap | Interest rates | Long-term global rates |

| USD 5-year swap | Interest rates | Medium-term global rates |

| USD 3-month Libor | Interest rates | Short-term global rates |

| Gold spot | Commodity | Inflation hedge, metals |

| Brent crude oil futures | Commodity | Energy |

Figure 15.1 shows the bubble measure for the S&P 500 Index. The bubble peaked at the end of 1995, but it turned out to be a false signal—the rally developed into a long-term uptrend that lasted until mid-2000. Due to the adaptive nature of the bubble, it eased off and maintained a moderately positive level up to 1999 (see arrow). Generally, the bubble peaked and troughed in tandem with the index (see circles in Figure 15.1).

FIGURE 15.1 Bubble Measure for S&P 500 Index

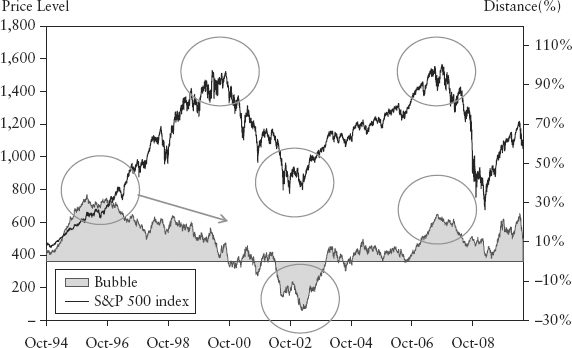

Figure 15.2 shows the buVaR and the ETL of S&P 500 index. Using our definition of upper bound ψ, the buVaR’s peak during the run-up to the 2008 credit crisis is slightly higher than the ETL’s peak during that crisis. As seen, buVaR leads ETL (or any conventional VaR measure) significantly and peaks almost one year ahead of the crash.

FIGURE 15.2 BuVaR and ETL for S&P 500 Index

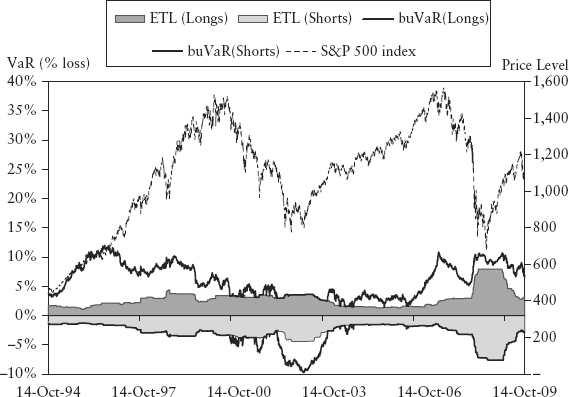

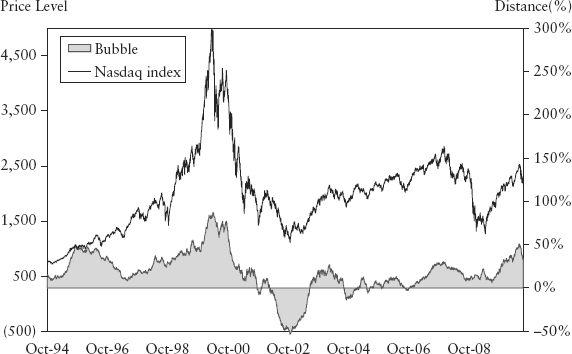

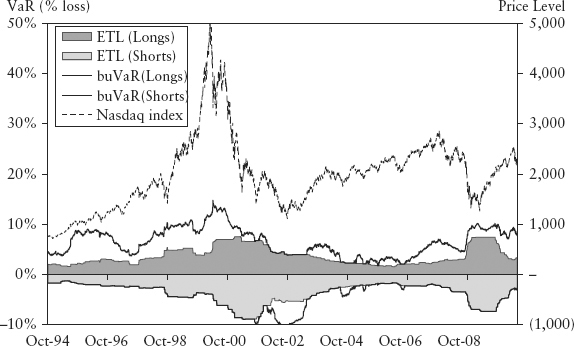

Figure 15.3 shows the bubble measure for the Nasdaq 100 index. The peak/trough of buVaR corresponded to the peak/trough of the index. The Nasdaq crash in 2000 was extremely sharp; had we used a simple moving average to construct the inflator, the bubble meter would have flipped to a negative reading when the price collapse reached 50% of the full crash amount, and buVaR would have wrongly penalized short positions instead. Figure 15.4 shows the resulting buVaR for Nasdaq.

FIGURE 15.3 Bubble Measure for Nasdaq 100 Index

FIGURE 15.4 BuVaR and ETL for Nasdaq 100 Index

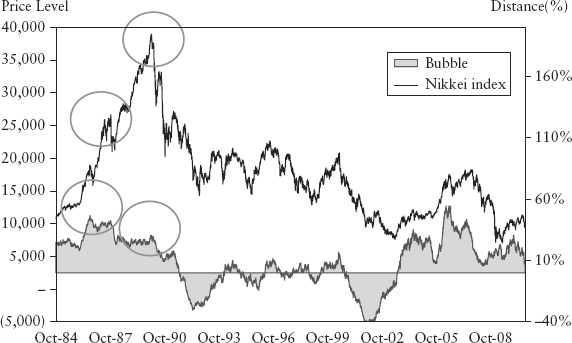

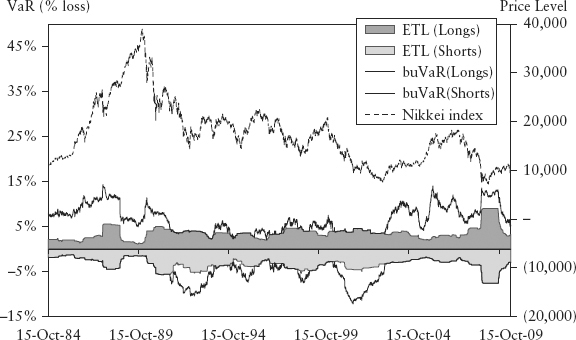

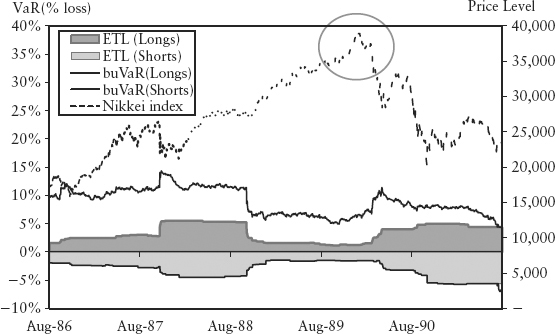

Figure 15.5 shows the bubble measure for the Nikkei 225 index. The bubble significantly penalized positions in a countercyclical way at major peaks and troughs (see circles in Figure 15.5). This is less obvious in the buVaR chart in Figure 15.6 because the level of the ETL was ultralow in 1989, which lessened the impact of the inflation.

FIGURE 15.5 Bubble Measure for Nikkei 225 Index

FIGURE 15.6 BuVaR and ETL for Nikkei 225 Index

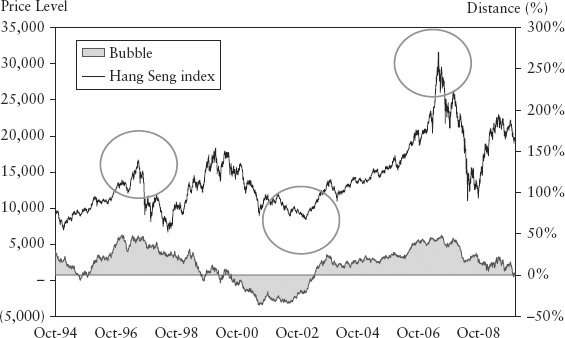

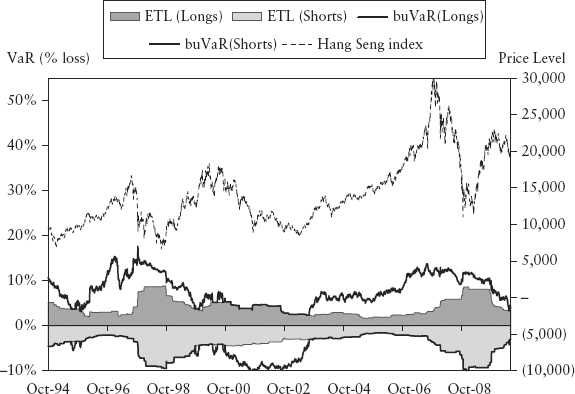

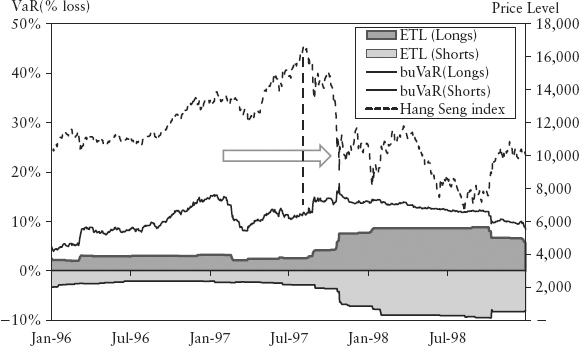

Figure 15.7 and Figure 15.8 show the bubble measure and buVaR for the Hang Seng index. The bubble penalized positions in a countercyclical manner ahead of peaks and troughs (circled). Notice that the bubble did not penalize every peak and trough, only the major unsustainable ones normally associated with crashes and manias. The circles correspond to the Asian crisis and the credit crunch.

FIGURE 15.7 Bubble Measure for Hang Seng Index

FIGURE 15.8 BuVaR and ETL for Hang Seng Index

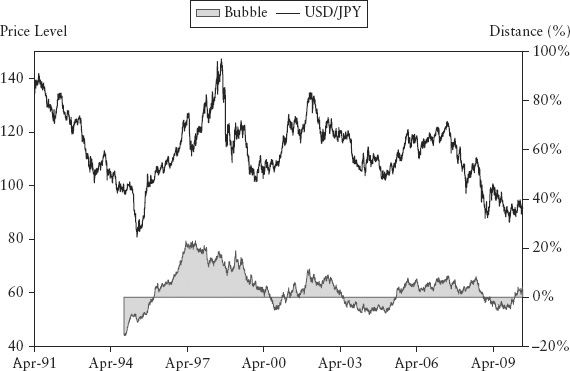

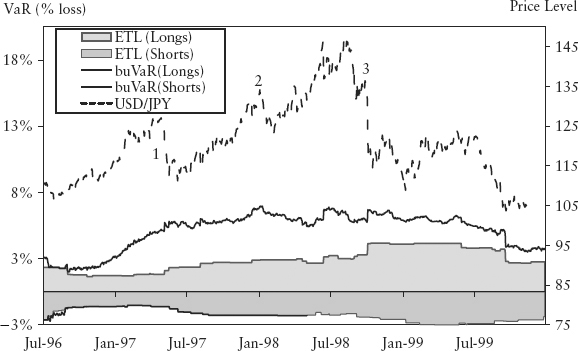

Figures 15.9 and 15.10 show the bubble measure and buVaR for the USD/JPY exchange rate. Major peaks and troughs were strikingly detected by the bubble measure. The buVaR was highest during the period in 1997–1998 when the Bank of Japan (BoJ) actively defended the yen against speculators as a policy.

FIGURE 15.9 Bubble Measure for the USD/JPY Exchange Rate

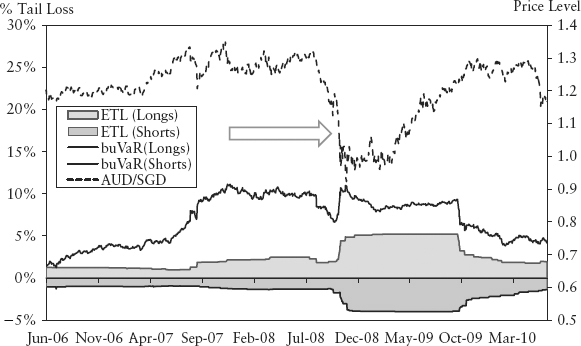

Due to the exponential function exp(.) in the response function, minor peaks/troughs in the bubble will translate into immaterial buVaR enhancement, and should not be our focus. Instead, buVaR is designed to catch major crashes and manias. This is apparent in Figures 15.11 and 15.12, which show the bubble measure and buVaR for the AUD/SGD exchange rate. The left circle shows a major bubble, but when it failed to burst, the measure rapidly tapered off by design (the arrow). The right circle shows the carry trade bubble finally burst, triggered by the 2008 crisis, and was forewarned by buVaR.

Swaps and treasury bonds of major currencies tend to be highly correlated because central banks of major countries often coordinate their monetary policies to maintain economic and market stability. Hence, for the purpose of testing, we can use USD swap rates as a benchmark for global interest rates. Figures 15.13 and 15.14 show the bubble measure and buVaR for the 10-year USD swap rate. The major peaks and troughs are circled in Figure 15.13.

Figures 15.15 and 15.16 show the results for the 5-year USD swap, which looks similar to that for the 10-year USD swap. This is because the midsection and long end of the same curve are expected to be highly correlated as they are influenced by common risk drivers.

Figures 15.17 and 15.18 show the results for the 3-month Libor rate which, in contrast, does not look at all like the 5-year and 10-year swaps. In fact, the Libor rate chart looks toothed and irregular because the short end of the curve (overnight rate to 3-month rate), which acts as an anchor for the entire yield curve, seldom moves. Central banks control the overnight rates. The only time short rates really move is when there is an actual (or perceived) central bank rate cut or rate hike. And since such actions usually come in dosages of 25bp or multiples of it, the short rate time series becomes toothed. The problem with unsmooth time series is that it throws off most continuous-time modeling. As such, the bubble measure becomes ineffective—for example, the peak in Libor rates in Jun 2007 was utterly missed out by the model.

The solution to this problem is a simple one—since it is inconceivable that different parts of the same yield curve would be at different business cycles (after all, they relate to the same economy), we really only need one single liquid benchmark from the curve for the purpose of deriving the bubble (which will be used for all tenors). The five-year point is preferred for two reasons: Most companies raise medium term funds by issuing corporate bonds in this part of the curve, and default swaps are also the most liquid for five years.

Figure 15.19 shows the bubble measure for the gold spot price (in USD). BuVaR did well by penalizing the longs markedly on three occasions (see Figure 15.20) during the bull run, but when the rally proved unstoppable, the buVaR subsided temporarily.

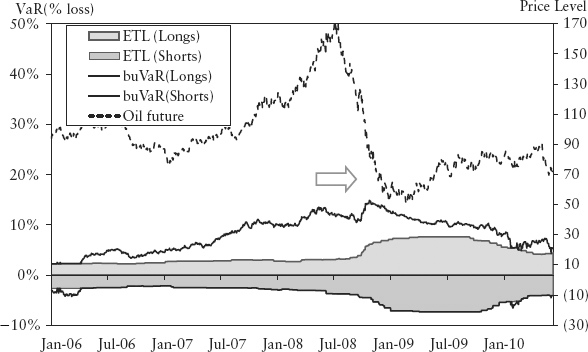

Figures 15.21 and 15.22 show the bubble and buVaR for Brent crude oil futures (of the near month contract). Remarkably, the bubble measure preempted every major oil price spike in recent history (circled in Figure 15.21).

BuVaR is designed to anticipate market bubbles and make provision against an impending crash. In this section, we look at major crises and extreme events in the history of financial markets, to test if buVaR was able to penalize players ahead of the crash. The test is deemed successful if the bubble measure inflates and buVaR peaks before the crash occurs. The infamous events in Table 15.2 are tested.

TABLE 15.2 Key Negative Events Found in Recent Financial History

| Asset | Asset Class | Crash Events |

| S&P 500 Index | Equity | 2008 Credit crunch |

| Dow Jones Index | Equity | 1987 Black Monday crash |

| Nasdaq 100 Index | Equity | 2000 Internet bubble burst |

| Nikkei 225 Index | Equity | 1989 Japan’s asset bubble burst |

| Hang Seng Index | Equity | 1997 Asian crisis |

| USD/JPY | Forex | 1998 Bank of Japan intervention |

| AUD/SGD | Forex | 2008 Yen carry unwind |

| Brent crude oil futures | Commodity | 2008 Oil price bubble burst |

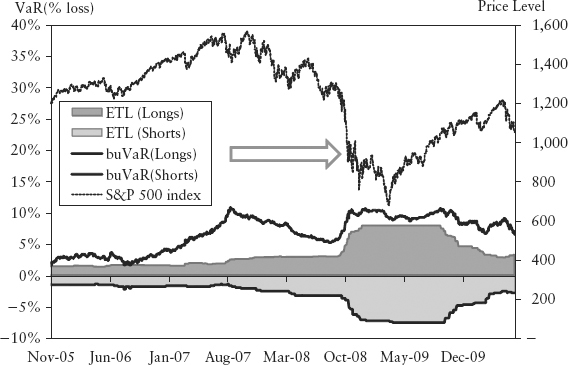

Figure 15.23 shows the buVaR of the S&P 500 index during the 2008 credit crunch. It is not easy to pinpoint exactly when the crash formally occurred since it cascaded down. The arrow indicates the lead time from when the bubble peaked to when the price collapse was steepest. The bubble peaked in July 2007 just as the S&P index (and the buVaR)1 reached its high, one year ahead of the crash, and maintained a significant penalty on the long side.

FIGURE 15.23 The 2008 Credit Crunch and the BuVaR of S&P 500 Index

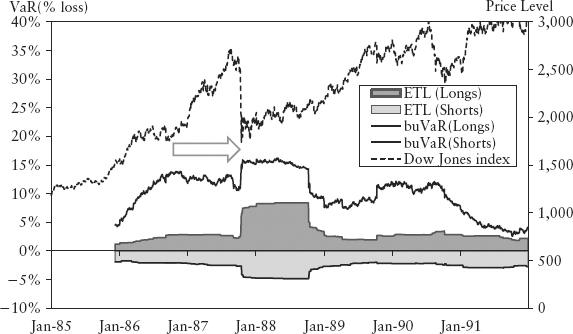

Figure 15.24 shows the buVaR of the Dow Jones index around the Black Monday (1987) crash, which registered a 25% single day freefall. Again, the arrow indicated a one-year lead time. The bubble measure was preemptive, and the penalty was maintained until after the crash.

FIGURE 15.24 The 1987 Black Monday and the BuVaR of Dow Jones Index

Figure 15.25 shows the buVaR of the Nasdaq index when the Internet bubble burst in 2000. It may appear that buVaR peaked after the initial collapse, but the bubble measure actually peaked just as the Nasdaq made its high (Figure 15.3).

FIGURE 15.25 The 2000 Internet Crash and the BuVaR of Nasdaq Index

Figure 15.26 shows the buVaR of the Nikkei 225 index during the 1987 stock market crash and Japan’s asset bubble burst in 1989. It would seem in 1989 (circled in Figure 15.26) buVaR did not significantly penalize the long side. This is because the ETL itself is ultralow, even though the bubble measure peaked (see circle in Figure 15.5) its multiplicative effect is diluted.

FIGURE 15.26 Japan’s Asset Bubble Collapse (1989) and the BuVaR of Nikkei Index

Figure 15.27 shows the buVaR of the Hang Seng index during the 1997 Asian crisis. The buVaR peaked about six months ahead of the crash. In fact, the dotted vertical line indicates where the bubble measure peaked just before the crash (see also Figure 15.7).

FIGURE 15.27 The Asian Crisis (1997) and the BuVaR of Hang Seng Index

Figure 15.28 shows the buVaR of USD/JPY exchange rate during the BoJ intervention period in 1997–1998. There were multiple rounds of BoJ purchases of yen; three of the largest collapses were picked up by buVaR, including the famous yen carry unwind on October 7 and 8, 1998, that was triggered by the Russian debt default (August 98) and LTCM collapse (September 98). The inflation of VaR was significant and preemptive, and would have discouraged (bank) speculators from shorting the yen during that period.

FIGURE 15.28 BoJ USD/JPY Exchange Rate Intervention 1997–1998 and BuVaR of Yen

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P.

Figure 15.29 shows the buVaR of the AUD/SGD exchange rate during the yen carry unwind in 2008. The credit crunch sparked a massive flight-to-safety and exiting of yen carry trades,2 a favorite yield pick-up trading strategy among institutional investors. Because of the large differential between AUD and SGD interest rates, the AUD/SGD was a favorite choice for such trades. BuVaR peaked almost six months ahead of the AUD/SGD collapse.

FIGURE 15.29 Yen Carry Unwind in 2008 and BuVaR of AUD/SGD Exchange Rate

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P.

Figure 15.30 shows the buVaR of crude oil futures during the bursting of the oil bubble in 2008. Both the bubble measure (Figure 15.21) and buVaR peaked ahead of the crash by about three months.

FIGURE 15.30 Oil Bubble Burst in 2008 and BuVaR of Brent Crude Oil Futures

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P.

We can draw some general conclusions from the tests in Sections 15.1 and 15.2. BuVaR peaks and troughs ahead of the market, often with a comfortable lead time for banks to trim positions. In rare situations of ultralow and declining volatilities, buVaR’s effectiveness may be hampered. In contrast, conventional VaR is always one step behind the market in a crisis.

BuVaR is designed to act as a countercyclical measure of risk. To qualify, we need to test whether the inflator synchronizes with the business cycle. There are many ways in the statistical literature to measure the business cycle. One popular method is the HP filter, which assumes that a time series xt can be divided into two components: the trend (lt) and the cycle (st), such that xt = lt + st. Hodrick and Prescott (1981) proposed that the trend can be backed out by optimizing the following equation:

where λ is the smoothing parameter. The business cycle is derived by simply taking the ratio between the price series and the cycle, hence xt/st. Hodrick and Prescott suggest setting λ = 1,600 for quarterly data. Ravn and Uhlig (2002) proposed a way to adjust λ for data of different frequencies—it is optimal to multiply λ with the fourth power of the observation frequency ratio, for example, since we use daily data,3 λ should be (90)4 1,600 = 104,976,000,000.

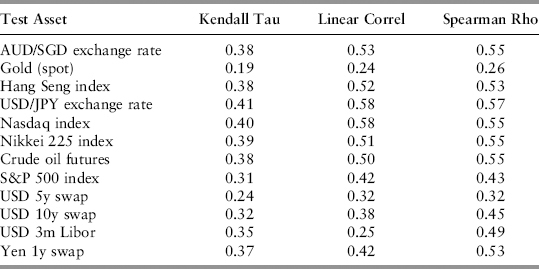

Specifically, we want to test if the bubble indicator moves in correlation with the business cycle. Since there is no fundamental reason to expect the relationship to be a linear one, we use all three measures from Section 2.4: linear correlation, Kendall tau, and Spearman rho.

Correlation should be calculated on changes rather than on price levels; otherwise effects from long-term trends can result in extremely misleading correlation values. For example, if one price series oscillates around a long-term bullish trend and the other price series oscillates around a bearish trend, the correlation of prices would imply that the variables are inversely correlated, even if the timing of the upswings and downswings are perfectly in step. The computation is done using monthly changes (data from December 1993 to June 2009) because daily changes can be noisy.

As per Table 15.3, the correlation results are generally positive for all three measures and significantly different from zero (or no relationship). This suggests that the buVaR methodology can produce a risk metric that is correlated to the business cycle. Therefore, buVaR can be used for the computation of countercyclical capital buffers.

TABLE 15.3 Correlation Tests of Bubble Measure versus Business Cycle (December 1993 to June 2009)

The correlation result in Table 15.3 is not perfect because the bubble is designed to not just track the cycle faithfully, but to also adapt to changing conditions automatically. In particular, it must widen when a market bubble is forming, it must not follow when the price crashes, and it must shrink during extended periods of gradual growth. These adaptive benefits mean that the correlation, while reasonably positive, will not be very high.

As seen in the few examples in Chapter 14, credit buVaR is non-cyclical in the sense that there is no dependency on the business cycle. It is designed to detect the occurrence of credit escalation and then penalize long credit positions in a sensible way.

There is no purer measure of default expectation than credit spread itself. Since expectations are forward looking, a spread escalation is preemptive of a default. Because the spread is used to inflate credit buVaR, there is no issue with timing, the effects of inflation will always be immediate—thus no timing test is required. The crucial issue is then the setting of ω2. How conservative (or penal) should one make credit buVaR?

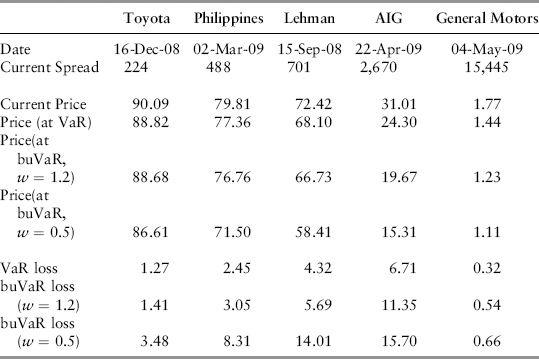

To answer this question, let’s look at credit buVaR for five selected issuers that have experienced the credit crunch in 2008. We convert five-year spreads to bond prices using the same model assumptions as in Chapter 14, in particular, the five-year swap rate and the bond’s coupon are taken to be 2.57%. Two sets of results are calculated, for ω2 = 1.2 and, more conservatively, for ω2 = 0.5.

Table 15.4 revisits the conditions during the 2008 crisis; particularly the spreads are recorded on those dates when (credit) buVaR reached its peak for each issuer. The buVaR and VaR are expressed as shifted price level and dollar loss. For example, in the case of Toyota, on December 16, 2008, its VaR is a loss of $1.27 from 90.09 to 88.82 for $100 standard notional.

TABLE 15.4 Summary Calculation When Credit BuVaR Is at Its Peak

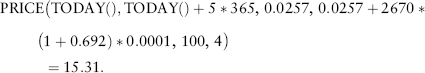

For each individual issuer, its spread is tabulated. Assuming a five-year bond for the issuer, its prevailing price and shifted price are computed using Excel function PRICE(.). For example, to calculate the AIG bond price after being shifted by buVaR of 69.2%4 (with ω2 = 0.5) use:

As expected, ω2 = 0.5 produces more conservative buVaR results than ω2 = 1.2; that is, the dollar loss is larger. As we shall see, the rapidity of credit deterioration (when it occurs) calls for a penal minimum capital regime. Let’s look at a few examples.

Figure 15.31 shows the buVaR for Lehman five-year CDS. Its spread broke the 200 level on February 15, 2008, and then again on May 22, 2008, and deteriorated rapidly. Lehman defaulted 16 weeks later when spreads were at 701. Two important lessons for modeling are (1) default is not a jump process, there is always a warning signal in the form of spread escalation; (2) it can happen very quickly and sometimes discontinuously (in this case at 701). If a five-year bond were to deteriorate continuously until default, Lehman would have escalated to 5,800bp (assuming 10% recovery). However, the market expected a Fed bailout so spread widening was not drastic. When the rescue plan failed, the bankruptcy surprised the market and trading stopped abruptly.

The same pattern is shown in the case of General Motors (see Figure 15.32). Its spread broke 1,000 on May 23, 2008 (the same time as Lehman’s breakout!). It took the market 11 months to reach the high of 21,000bp. The same observations are applicable here: (1) There is ample warning time, and (2) the spread escalation was rapid. In practice, once spreads escalate to above 4,000bp to 5,000bp, there is very little a bank can do to trade out of the position since liquidity will dry up and most counterparties will treat it like an impaired asset and look for off-market settlement. While the time series was not disrupted, the bond has effectively defaulted on an MTM basis (see the last column of Table 15.4). Notice the buVaR started coming off as the spread went above 15,445. This is to constrain the shifted price from falling below zero.

A notable observation is that conventional spread VaR is a poor measure of default risk. The VaR for GM moved up very little throughout the crisis—it is capturing changes in volatility while ignoring the rapid rise in spread levels. It is possible for spreads to trade at high levels but with low volatility. Spread VaR completely missed the warning signs.

Figure 15.33 shows the spread of AIG, which did get a government bail-out package. The spread broke 500 on September 11, 2008 and reached 2,500bp just seven weeks later. From these examples, it would seem that banks may have as little as two months to react to a credit deterioration, say, by cutting positions.

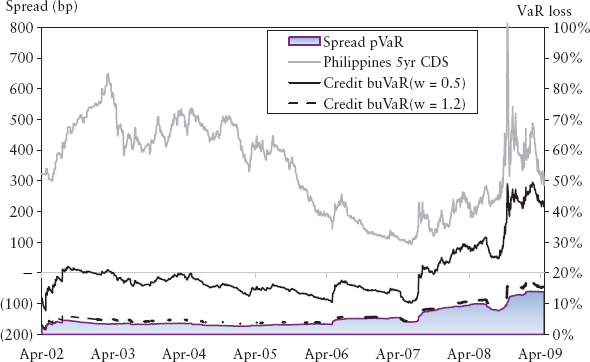

Figure 15.34 and Figure 15.35 are two examples of issuers that were negatively affected by the sentiment during the credit crunch, but were never in danger of default. (It is inconceivable that the Philippine government would declare a debt moratorium because of contagion from the subprime crisis; the economics are too far apart.) The spread escalation was equally rapid, but the magnitude was many times smaller.

FIGURE 15.35 BuVaR for the Philippines Government Five-Year CDS Spread

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P.

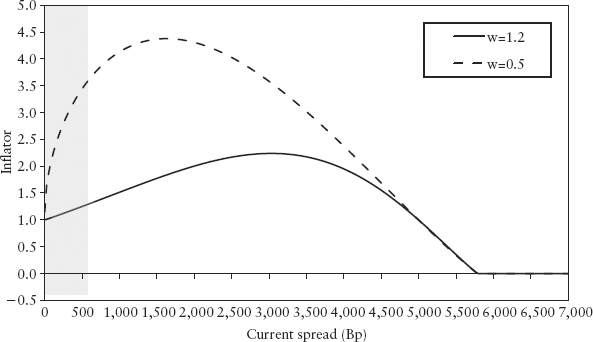

These five examples have highlighted a common theme: Credit deterioration is very rapid when it occurs. Figure 15.36 shows the response function for ω2 = 1.2, ω2 = 0.5. The shaded region is the “normal” trading zone when the market is not in distress. When credit escalation occurs, the credit spread accelerates rapidly above 500bp (for instance) to outside the normal zone.

FIGURE 15.36 Response Function for Two Settings of ω2 = 1.2, ω2 = 0.5

This phenomenon argues for a more penal setting (ω2 = 0.5) since it will be too late (and counterproductive) to raise minimum capital only when the issuer company is rapidly falling apart. A capital buffer for default risk needs to be built up when spreads are still trading in the normal zone, but showing signs of widening.

Using ω2 = 0.5 (dotted line) as an example, let’s examine how penal buVaR is. When the spread is at 20 (AAA-rated levels) the inflator is at 1.5, which means that for the best corporate issuers a long credit position is taken to be 50% more risky than a short credit position. When the spread is at 350, the average five-year spread of Philippine CDS during the period shown in Figure 15.35, the inflator is at 3.0. This means for high-yield issuers, a long credit position is three times riskier than a short credit position. For ω2 = 0.5 the inflator is capped at 4.4 times.

It is true that a short credit position has no risk of default unlike a long position. But is it reasonable to penalize the long side multiple times more than the short side from the default risk standpoint? We offer a heuristic argument.

The credit spread puzzle was well researched as discussed by Amato and Remolona (2003)—it refers to the fact that corporate credit spreads are much wider than what expected default would imply. The latter is derived from historical default statistics available from rating agencies. Studies by Elton et al. (2001) confirmed that expected default risks contributed no more than 25% of observed spreads. Georges et al. (2005) showed that results can differ widely depending on the methodology, the default cycle, and recovery rate assumptions. In particular, for the period of high default cycle, the proportion for Baa bonds can go as high as 71% of estimated spread, assuming a recovery rate of 49%. For this case, when the recovery assumption is reduced to 40%, the proportion increases to 83%.

Hence, depending on the severity of the default cycle, the proportion of default risks in credit spreads can be as high as 83%. The rest is explained by risk premium (arising from spread volatility), liquidity premium, and difficulty in diversification of tail-risks. We argue that a short CDS position is free from default risk, hence, should have risks unrelated to default that can be as low as 17% of total risk priced into credit spreads. We can then infer the ratio of risks between long and short CDS.

As a rough guide, if up to 83% of the spread is contributed by default risks (i.e., at least 17% by nondefault risks), then a long CDS is up to 100/17 = 6 times riskier than a short CDS. Hence, the inflator should range from 1 to 6 depending on the extent of credit deterioration, in general agreement with our cap of 4.4 times. Put another way, the incremental loss of buVaR over and above spread VaR (which just measures volatility) can be attributed to default risks.

In summary, credit buVaR provides an add-on buffer to conventional spread VaR on the long side to account for default risks. The response function is theoretically appealing, and we justified its interpretation by referring to research on the credit spread puzzle.

1. The buVaR does not always peak at the same time as the bubble since, if conventional VaR is very small, its inflation may not produce a sizable buVaR. In such cases, the bubble peak often leads the buVaR peak.

2. The trader invests in a high-yielding currency using funds borrowed in a low-yielding currency. If the exchange rate remains unchanged, the trader stands to earn the interest difference between the two currencies as an accrual carry profit. The strategy is dubbed yen carry because yen, with near zero rates, is traditionally used for this strategy.

3. We assume one quarter is 90 days. Free shareware implementation of the HP filter is available from the Internet. The reader can easily show that the result of the HP filter is similar to that of a low order (such as a cubic) polynomial fit, which is also commonly used by economists.

4. The calculation of 69.2% buVaR (which will shift the spread) is not shown here.