Big Lie #10

“America Is in the Midst of an Irreversible Moral Decline”

“THE END IS NEAR”

As a boy I became fascinated with frequent New Yorker cartoons (the only part of that magazine I actually read) depicting bearded, robed, and sandaled figures marching down city streets with placards proclaiming THE END IS NEAR.

In recent years, some of the nation’s most thoughtful social conservatives have embraced this apocalyptic message as their own, identifying America’s undeniable cultural decay as a steep, irreversible slide.

In 1996, Judge Robert Bork, an old friend and impeccably provocative professor from my days at Yale Law School, issued a best-selling denunciation of national decline entitled Slouching Towards Gomorrah. Possessing the requisite beard and robes (though he’d actually hung up his judicial garb eight years before), Judge Bork described the United States as a “degenerate society,” “enfeebled, hedonistic,” “subpagan,” and headed for “the coming of a new Dark Ages.” He urged his readers to “take seriously the possibility that perhaps nothing will be done to reverse the direction of our culture, that the degeneracy we see around us will only become worse.”

Three years later, Paul Weyrich, one of the widely admired founding fathers of the modern Religious Right (and the originator of the term “Moral Majority”), published a despairing open letter to his fellow conservatives. “The culture we are living in becomes an ever-wider sewer,” he wrote in February 1999, in the midst of the Clinton impeachment crisis. “In truth, I think, we are caught up in a cultural collapse of historic proportions, a collapse so great that it simply overwhelms politics. . . . I no longer believe there is a moral majority. I do not believe that a majority of Americans actually shares our values. . . . I believe that we probably have lost the culture war.”

In the same era, the redoubtably conservative Insight magazine ran an article with the headline “Is Our Society Worth Saving?” and, after reviewing omnipresent signs of rot, allowed that the answer might well be no.

More recently, John F. MacArthur, the influential California pastor, president of the Master’s College, and author of some fifty books on the Bible and contemporary life, declared: “There comes a point in God’s dealing with men and nations, groups of people, when He abandons them. . . . Sin is so rampant in our country, it is so widespread, it is so tolerated by people in leadership and even people in the church, it is so widely tolerated it is pandemic: it is endemic; that is, it is in the very fabric of our life that I believe God has just taken away the restraining grace that might preserve our nation, and has let our nation run to its own doom.”

Dr. MacArthur brings an unapologetically Christian perspective to his pronouncements of impending catastrophe, while the perpetually enraged talk radio ranter Michael Savage joins the Loony Left in predicting the coming onset of Nazism. “I am more and more convinced that we have a one-party oligarchy ruling our nation,” he warned in The Savage Nation, his 2002 best seller. “In short, the ‘Republicrats’ and ‘Demicans’ have sacked our Constitution, our culture, our religions, and embarrassed the nation. . . . The last years of the Weimar Republic of pre-Nazi Germany come to mind—where decadence completely permeated a free society.”

While most Americans remain untroubled by the prospect of imminent Hitlerism, it’s impossible for any fair-minded observer to ignore or deny the abundant indications of long-term cultural decline. A review of major changes in American society over the past half century provides powerful evidence of moral decay: the collapse of family norms, an appalling coarsening of the popular culture, and the fraying of any national consensus on standards of right and wrong.

In March 1993, William J. Bennett, who previously led the battle against demons of decadence as secretary of education and “drug czar,” published his first “Index of Leading Cultural Indicators,” identifying “substantial social regression.” Since 1960, out-of-wedlock births had increased by 400 percent, violent crime by 500 percent, and teen suicide by 300 percent. Even my unflappable friend Bennett, by no means an alarmist or doomsayer, looked at the data at the time with something like despair and concluded that “the forces of social decomposition are challenging—and in some instances overtaking—the forces of social composition.”

The most pertinent question for today’s parents and policy makers is whether that process of decomposition will continue, and whether the destructive trends identified in the 1990s have become unstoppable.

Most recently one of Dr. Bennett’s associates on the “Cultural Indicators” project, Peter Wehner, raised the possibility that most of the distressing phenomena they identified fifteen years ago have already reversed themselves, providing significant signs of social revival. Wehner, now a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, prepared a stunning update for the December 2007 issue of Commentary magazine. Writing with Yuval Levin, Wehner declared: “Just when it seemed as if the storm clouds were about to burst, they began to part. As if at once, things began to turn around. And now, a decade-and-a-half after these well-founded and unrelievedly dire warnings, improvements are visible in the vast majority of social indicators; in some areas, like crime and welfare, the progress has the dimensions of a sea-change.”

It’s impossible to evaluate this apparent change of direction, or its relevance to the most recent pronouncements that the end is near, without placing the debate in its proper historical perspective. As it turns out, worried moralists have railed against corruption, sinfulness, and the end of American civilization since the very beginning of American civilization—the earliest days of colonial settlement.

FOUR HUNDRED YEARS OF IMMINENT DOOM

We prefer to think of William Bradford, the longtime leader of Plymouth Colony, as a courageous man of faith who calmly overcame every obstacle to establish the Pilgrims’ settlement in the Massachusetts wilderness. Some twenty-five years after taking shore at Plymouth Rock, however, Bradford became the first major American commentator to see evidence of deadly moral decay and a betrayal of his society’s heroic past.

In 1645, he made one of the last significant entries in his journal while in an obviously mournful mood:

O sacred bond, which inviolably preserved! How sweet and precious were the fruits that flowed from the same! But when this fidelity decayed, then their ruin approached. O that these ancient members had not died or been dissipated (if it had been the will of God) or else that this holy care and constant faithfulness had still lived, and remained with those that survived, and were in times afterwards added unto them. But (alas) that subtle serpent that slyly wound himself under fair pretenses of necessity and the like, to untwist these sacred bonds and ties. . . . It is now a part of my misery in old age, to find and feel the decay and want thereof (in a great measure) and with grief and sorrow of heart and bewail the same. And for others’ warning and admonition, and my own humiliation, do I here note the same.

Historians argue about the reasons Bradford looked so harshly at his own prospering and secure settlement. A few years earlier, in the “horrible” year of 1642, a Plymouth youth named Thomas Granger had to be executed for the unspeakable sin of bestiality (along with all the animals he had defiled). Whatever the cause, virtually every subsequent generation echoed Bradford’s certainty that new attitudes, sins, and shortcomings proved unworthy of a sacred, noble past.

One of the old Pilgrim’s spiritual successors, the great preacher (and president of Princeton) Jonathan Edwards, wrote that the 1730s represented “a far more degenerate time . . . than ever before.” In his immortal 1741 sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” he riveted the devout Puritan churchgoers in Northampton, Massachusetts, and Enfield, Connecticut, by telling them: “Yea, God is a great deal more angry with great numbers that are now on earth: yea, doubtless, with many that are now in this congregation, who it may be are at ease, than he is with many of those who are now in the flames of hell. . . . The wrath of God burns against them, their damnation does not slumber; the pit is prepared, the fire is made ready, the furnace is now hot, ready to receive them; the flames do now rage and glow. The glittering sword is whet, and held over them, and the pit hath opened its mouth under them.”

Almost exactly a century later another New England preacher, antislavery firebrand William Lloyd Garrison, deplored the impiety, hypocrisy, and degradation of his own temporizing generation: “I accuse the land of my nativity of insulting the Majesty of Heaven with the grossest mockery that was ever exhibited to man.” He also denounced the Constitution as “a covenant with death and an agreement with Hell” and frequently burned copies of the nation’s founding document to signify God’s righteous wrath.

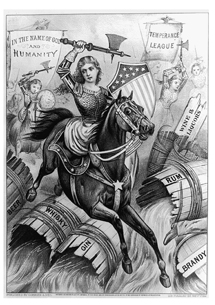

Billy Sunday, former major league outfielder (for the Philadelphia Phillies and other teams) and famous revivalist, led another moral crusade against the decadence of early-twentieth-century America. Proclaiming himself “the sworn, eternal, and uncompromising enemy of the Liquor Traffic,” he fervently pledged that “I have been, and will go on, fighting that damnable, dirty, rotten business with all the power at my command.” The evangelist also opposed public dancing, card playing, attending the theater, reading novels, and baseball games on Sunday. Even before the “loss of innocence” associated with America’s entry into WorldWar I, he asked one of his huge audiences: “Did you ever know a time in all history when the world was worse than it is now? People are passing up the Church and the Prayer Meeting for the theatre, the leg show, and the movies. Oh, Lord, how we need someone to cry aloud, ‘Return to God!’”

These thundering denunciations by yesterday’s revivalists should remind twenty-first-century culture critics that they by no means count as the first of their countrymen to sound the alarm over rampant self-indulgence and imminent moral collapse. Even the most heroic generations in American history fell short of the one-dimensional, statues-in-the-park righteousness we love to impute to the supposedly simplerworld of the glorious past.

Colonial birth records confirm, for instance, that in the decades before the American Revolution a shockingly high percentage of first children (at times as high as 30 percent in some regions) arrived less than seven months after the wedding ceremony—a powerful indication that strict self-control escaped young Americans of more than two hundred years ago much as it escapes too many young people today. Even the noble and spectacularly gifted Founding Fathers struggled with the same temptations and foibles afflicting politicians (and others) of our era: Benjamin Franklin fathered an illegitimate son from an unidentified mother, married a woman who lacked a proper divorce, and conducted numerous flirtations during diplomatic missions to France; Thomas Jefferson (as a widower) carried on a deep love affair with a beautiful married woman and probably indulged in a long-term relationship with his own slave Sally Hemings beginning when she was thirteen; Alexander Hamilton engaged in a torrid connection with a married woman while paying blackmail to her husband; and Aaron Burr enjoyed literally scores of passionate affairs and faced persistent rumors of incest with his glamorous daughter.

In at least one area, today’s citizens display better discipline and higher moral standards than our Revolutionary forebears. In their essay “Drinking in America,” historians Mark Lender and James Martin report: “One may safely assume . . . that abstemious colonials were few and far between. Counting the mealtime beer and cider at home and the convivial drafts at the tavern or at the funeral of a relative or neighbor, all this drinking added up. . . . While precise consumption figures are lacking, informed estimates suggest that by the 1790s an average American over fifteen years old drank just under six gallons of absolute alcohol a year. . . . The comparable modern average is less than 2.9 gallons per capita.” This consumption created worrisome problems with public drunkenness in Philadelphia, Boston, New York, and other colonial centers that mirrored, though never equaled, the appalling alcoholism that plagued London.

Such details from the historical record serve as a useful corrective to nostalgia for earlier eras of allegedly effortless moral purity. They also give the lie to the common assumption that social degradation is a one-way street that leads year by year, generation by generation, only downhill. When it comes to measures of morality, it would be more accurate to say that America has experienced a dizzying roller coaster of steep ups and downs, zigzags, climbs and reverses, and even loop-the-loops.

“Show Me Something Worse!”

Each generation of Americans sees its own era as uniquely corrupt, but when it comes to prostitution and the mass degradation of women, the last years of the nineteenth century stood out as especially shameful. In City of Eros (1992), historian Timothy J. Gilfoyle looks at surviving records and suggests that as many as one out of six female New Yorkers may have worked full-time as prostitutes. With cities teeming with lonely, homesick, and predominantly male immigrants, young women who arrived from Southern Europe, Eastern Europe, or Asia either got snapped up as brides or, too often, found themselves forced into brutal “white slavery.”

In 1892, Reverend Charles Parkhurst of Madison Square Presbyterian Church went undercover to expose New York’s savage “underworld” and confirm his charges of corruption against city officials. At each stop, Parkhurst ordered the private detective guiding him, “Show me something worse!” and encountered excesses of sadism and pedophilia (involving both girls and boys) to disgust observers of any century. When he went public with his revelations, the press and legal establishment (including a committee of the legislature) joined his crusade against vice. A reform ticket swept Tammany Hall out of office in the next city election at the same time that Emma Willard of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union intensified her campaign against white slavery everywhere. By the end of World War I in 1918, reformers had made noteworthy progress against forced prostitution, emphasizing hygienic arguments and warning of the impact of venereal disease.

GREAT DISRUPTIONS, GREAT REDEMPTIONS

Francis Fukuyama of Johns Hopkins University, author of The Great Disruption, writes trenchantly: “While conservatives may be right that moral decline occurred over the past generation, they cannot be right that it occurs in every generation. Unless we posit that all of human history has been a degeneration from some primordial golden age, periods of moral decline must be punctuated by periods of moral improvement.” Impassioned scolds such as Bradford, Edwards, Garrison, and Sunday actually helped facilitate such “periods of moral improvement,” pushing and prodding toward the various awakenings and revivals that changed American society for the better.

Religious historians refer to four distinct “Great Awakenings” that profoundly influenced the course of history and the ethical outlook of the populace. The first, from the 1730s through the 1750s, was led by fiery preachers such as Jonathan Edwards and British visitors George Whitefield and the Wesley brothers, and spread from rural districts to the largest cities, helping lay the groundwork for the American Revolution. The second, from 1800 through the 1830s, brought camp meetings that drew tens of thousands even in remote frontier settlements, the founding of pious, nonconformist sects (including the Mormon Church), and new energy for the antislavery and women’s suffrage movements. The Third Great Awakening, from the 1880s through the 1900s, brought the Holiness Movement, the beginnings of American Pentecostalism, Christian Science, the Social Gospel, Progressive politics, and the resurgent temperance crusade against alcohol. Many sociologists and theologians see a Fourth Great Awakening beginning in the late 1970s and continuing to the present day, evidenced by the power of the so-called Religious Right, the growth of evangelical “megachurches,” and an immensely expanded Christian influence in popular culture. Regardless of how one evaluates the significance and lasting impact of each of these periods of revival, they suggest that the nation’s moral and religious history has never followed a straight line toward degeneracy and shattered traditions.

In her supremely valuable book The De-Moralization of Society, historian Gertrude Himmelfarb focuses on the British model to show that faith-based reformers can exert a potent impact on a nation’s manners and morals, virtues and values. The Victorian era, popularly identified with restrictive and judgmental codes of behavior, actually represented a conscious reaction to the excesses and debauchery of the 1700s. The raising of social standards—readily apparent in statistics on illegitimacy, drunkenness, crime, abandonment of children, and more—resulted from conscious efforts by mobilized moralists. Himmelfarb writes:

In addition to societies for the promotion of piety and virtue, others were established for the relief of the poor and infirm—for destitute orphans and abandoned children, aged widows and penitent prostitutes, the deaf, dumb, blind, and otherwise incapacitated. . . . The idea of moral reformation also extended to such humanitarian causes as the elimination of flogging in the army and navy, the abolition of the pillory and public whipping, the prohibition of cockfighting, bull-baiting, and bearbaiting, and, most important, the abolition of the slave trade . . . Less formally, but no less effectively, they promoted those manners and morals that have come to be known as “Victorian values.” . . . The “moral reformation” initiated in the late eighteenth century came to fruition in the late nineteenth century.

The reformers refused to see moral failings as inevitable, intractable, or imposed by a higher power. In fact, the Victorian “remoralization” represents one of the most spectacular examples of self-conscious social betterment in all of human history—an improvement in which the United States ultimately followed Britain’s example. As Himmelfarb concludes: “At the end of the nineteenth century, England was a more civil, more pacific, more humane society than it had been in the beginning. ‘Middle-class’ manners and morals had penetrated into large sections of the working classes.”

Francis Fukuyama notes the same wholesome transition as a prime example of a “great redemption” following one of history’s periodic “great disruptions.” He notes that “in both Britain and the United States, the period from the end of the eighteenth century until approximately the middle of the nineteenth century saw sharply increasing levels of social disorder. Crime rates in virtually all major cities increased. Illegitimacy rates rose, families dissolved, and social isolation increased. The rate of alcohol consumption, particularly in the United States, exploded. But then, from the middle of the century until its end, virtually all of these social indicators reversed direction. Crime rates fell. Families stabilized, and drunkards went on the wagon. New voluntary associations—from temperance and abolitionist societies to Sunday schools—gave people a fresh sense of communal belonging.”

In addition to such sweeping changes of direction, the United States has experienced more limited periods of disruption or renewal. In the twentieth century, two world wars undermined the stability of family life and traditional mores, while the 1950s and its era of American dominance, prosperity, and religiosity saw dramatic improvements in divorce rates, criminality, drug and alcohol addiction, and access to higher education.

The countercultural explosions of the 1960s, viewed by many as an altogether fatal blow to parental authority, sexual self-discipline, sobriety, and the work ethic, gave rise in less than twenty years to the era of Reaganism and “Morning in America.” Some of the same baby boomers who turned on, tuned in, and dropped out, or traveled to Woodstock in 1969 “to get themselves back to the garden,” found their way home to church and suburb within twenty years, enrolling their children in religious schools and honoring the patriotic and entrepreneurial values the hippie era so colorfully scorned.

The rapid discrediting and dissolution of some of the most pernicious, drug-soaked notions of the once-celebrated youth culture (when’s the last time anyone glamorized a free-love commune or cult leader’s “family”?) demonstrated that major changes in manners and mores often prove ephemeral. While the most prominent and portentous Beatlesera philosophers, such as Charles Reich (The Greening of America), proclaimed a seismic shift in consciousness that would alter human attitudes forever, as it turned out, the big transformation didn’t even last past the 1970s.

Dr. Allan C. Carlson and Paul T. Mero, authors of The Natural Family: A Manifesto, see these advances and setbacks as part of a long, indecisive struggle to preserve “the natural family—part of the created order, imprinted on our natures, the source of bountiful joy, the fountain of new life, the bulwark of ordered liberty.” Industrialization brought the decisive break that undermined “the natural ecology of family life” when “family-made goods and tasks became commodities, things to be bought and sold,” with the factory and “mass state schools” taking children away from their previously home-centered lives. When the French Revolution gave ideological basis to these changes, “advocates for the natural family—figures such as Bonald and Burke—fought back. They defended the ‘little platoons’ of social life, most of all the home. They rallied the ideas that would show again the necessity of the natural family. They revealed the nature of organic society to be a true democracy of free homes.” This intimate restoration, they argue, made possible the sweeping reforms of the Victorian era.

Of course, other pendulum swings rapidly followed—with the totalitarian state power associated with Communist and Fascist ideology declaring open war on the family. When 1960s free spirits intensified their own struggle, Carlson and Mero report, they never won the expected easy or comprehensive victory. “As the culture turned hostile, natural families jolted back to awareness. Signs of renewal came from the new leaders and the growth of movements, popularly called ‘prolife’ and ‘pro-family,’ which arose to defend the natural family. By the early twenty-first century, these—our—movements could claim some modest gains.”

Such gains, which many social conservatives perversely refuse to recognize, need to be acknowledged and solidified to facilitate further progress.

IRREVERSIBLE, OR ALREADY REVERSED?

Those who insist on the definitive moral collapse of the United States as an unchallenged article of faith need to consider a shocking report in the New York Times in late November 2007:

New York City is on track to have fewer than 500 homicides this year, by far the lowest number in a 12-month period since reliable Police Department statistics became available in 1963.

But within the city’s official crime statistics is a figure that may be even more striking: so far, with roughly half the killings analyzed, only 35 were found to be committed by strangers, a microscopic statistic in a city of more than 8.2 million.

If that trend holds up, fewer than 100 homicides in New York City this year will have been strangers to their assailants. In the eyes of some criminologists, the police will be hard pressed to drive the killing rate much lower, since most killings occur now within the four walls of an apartment or the confines of close relationships.

The trend did hold up: throughout 2007 a total of 494 murders were committed in New York City, and well under 100 involved victimizing strangers.

The stunning enhancement of public safety in America’s largest city represents a stinging rebuke to those who persist in viewing the nation as a victim of ongoing moral breakdown and spreading anarchy. The change could hardly be more dramatic: New York recorded its greatest number of killings in a single year in 1990, with 2,245, and strangers committed a majority of those homicides. Seventeen years later, the city’s murder rate had fallen by more than three-fourths.

Other major cities may boast less spectacular progress than New York (with its two successive—and successful—crime-fighting Republican mayors), but they all show less violent and property crimes from their peaks some twenty years ago. While FBI crime statistics demonstrate an unfortunate uptick in criminal violence in the past two years (concentrated in cities such as Philadelphia and Washington, D.C.), the overall rate remains well below its peak. The criminal ethos regularly associated with social chaos and moral disorder has retreated across the country, and other indicators show a nation struggling to improve its spiritual and cultural health.

As Peter Wehner and Yuval Levin report in Commentary:

Teenage drug use, which moved relentlessly upward throughout the 1990s, declined thereafter by an impressive 23 percent, and for a number of specific drugs it has fallen still lower. Thus, the use of Ecstasy and LSD has dropped by over 50 percent, of methamphet-amine by almost as much, and of steroids by over 20 percent. . . . Teen use of alcohol has also fallen sharply since 1996—anywhere from 10 to 35 percent, depending on the grade in school—and binge drinking has dropped to the lowest levels ever recorded. The same is true of teens reporting that they smoke cigarettes daily.

In July 2007, the National Center for Health Statistics released more encouraging numbers involving the next generation of Americans. The Associated Press summarized the center’s findings: “Fewer high school students are having sex these days, and more are using condoms. The teen birth rate has hit a record low. More young people are finishing high school, too, and more little kids are being read to.”

Despite lurid publicity about a new “hookup culture” of casual sex among young people, the actual incidence of intercourse has markedly declined. The center’s study revealed that in 1991, 54 percent of high school students reported having had sexual intercourse, but by 2005, that number had dropped to 47 percent.

Even the Guttmacher Institute, affiliated with Planned Parenthood, reported similar declines in teenage sexual activity. In September 2006, the institute observed that “teens are waiting longer to have sex than they did in the past. . . . The proportion of teens who had ever had sex declined . . . from 55% to 46% among males” in just seven years between 1995 and 2002.

The reduced sexual activity has also brought about a sharp reduction in abortion rates. The Guttmacher Institute acknowledges that abortion rates peaked in 1981, just as our most outspokenly pro-life president, Ronald Reagan, entered the White House. In that year, doctors and clinics performed 29.3 abortions per 1,000 women aged 15 to 44. Twenty years later, after tireless efforts by pro-life activists and educators, that number had dropped steadily, year by year, all the way to 21.1, a reduction of nearly 30 percent. Meanwhile, the number of U.S. abortion providers went down by 11 percent in just four years between 1996 and 2000 and, according to all recent reports, continues to decline.

In April 2008 the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a report showing that between 1990 and 2004, the estimated abortion rate declined by a full 24 percent. In no single year did the rate even inch upward. Among the most vulnerable teenage mothers between the ages of fifteen and seventeen, the abortion rate fell a staggering 55 percent—at the same time that rates of teen pregnancy and live births also retreated.

In terms of family structure, the most common assumptions about the breakdown of marriage bear little connection to current realities. Professors Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers of the University of Pennsylvania write in the New York Times:

The great myth about divorce is that marital breakup is an increasing threat to American families, with each generation finding their marriages less stable than those of their parents. . . . In fact, the divorce rate has been falling continually over the past quarter century, and is now at its lowest level since 1970. . . . For instance, marriages that began in the 1990s were more likely to celebrate a tenth anniversary than those that started in the 1980s, which, in turn, were also more likely to last than marriages that began back in the 1970s. . . . The facts are that divorce is down, and today’s marriages are more stable than they have been in decades.

Despite deeply troubling increases in out-of-wedlock birth (a status now claimed by more than a third of newborn Americans), that phenomenon also may have begun to level off in recent years (most notably in the African American community). Moreover, the figures for children born outside of marriage do not register the widespread phenomenon of mothers and fathers who decide to marry and form a conventional family after the birth of their child. Though the white-picket-fence, “honey, I’m home” family looks far less solid and dominant than it did fifty years ago, the Census Bureau’s most recent statistics (2003) show a surprising total of 68.4 percent of all children below the age of eighteen (of all races) currently living in households with two parents; among white children that number reaches 74.2 percent. Despite its battering in the media, the family remains the normal, prevalent unit of social organization for the purpose of child rearing.

If the idealized family TV shows of the 1950s (Ozzie and Harriet, Father Knows Best, Leave It to Beaver) failed to portray the imperfections and complexities of real-life relationships, the lusty and lonely libertines of Desperate Housewives represent today’s realities just as poorly. In their enormously helpful book The First Measured Century, scholars from the American Enterprise Institute report: “The declining incidence of extramarital sex may seem implausible to television viewers who see a world of wholesale promiscuity in which marital fidelity is the exception rather than the rule. The data tell a different story.” The authors point out that “the most authoritative study of American sexual practices,” the 1992 National Health and Social Life Survey, reveals “an unmistakable decline in extramarital sexual activity during the latter part of the century, especially among married men.”

Finally, the progress on welfare, with its grim associations with dysfunction and dependency, has been nothing short of breathtaking. As Wehner and Levin summarize the situation, “Since the high-water mark of 1994, the national welfare caseload has declined by over 60 percent. Virtually every state in the union has reduced its caseload by at least a third, and some have achieved reductions of over 90 percent. Not only have the numbers of people on welfare plunged, but in the wake of the 1996 welfare- reform bill, overall poverty, child poverty, black child poverty, and child hunger have all decreased, while employment figures for single mothers have risen.”

The various numbers and analyses hardly paint a portrait of some golden age of moral rectitude or even of functional families—not at a time when, according to 2005 census figures, a record 37 percent of all American children enter the world without the benefit of married parents, or when cohabitation before marriage (despite indisputably increasing the likelihood of divorce) has become significantly more common (and even the norm to many young people).

Nevertheless, the claim that the nation faces irreversible moral decline can’t survive the incontrovertible evidence that some of the decay of previous decades has already been reversed. The effort to “remoralize” America after the disruptions of the 1960s has met with some success, and its future will depend to a great extent on the continued vitality of traditional religious faith.

Pledging Purity

Appalled by frightening rates of teen pregnancy, abortion, and sexually transmitted diseases, in 1993 a Nashville-based ministry of the Southern Baptist Convention launched an ambitious new program called “True Love Waits.” Participating youngsters took a public pledge, and signed a card, making “a commitment to God, myself, my family, my friends, my future mate, and my future children to a lifetime of purity including sexual abstinence from this day until the day I enter a biblical marriage relationship.” Within a year, more than 100,000 young people took the pledge, often in ecstatic and joyful public gatherings. By 2008, the Journal of Adolescent Health was reporting that an impressive 23 percent of American females between the ages of twelve and seventeen, and 16 percent of males, made public commitments to avoid sex before marriage. Some researchers questioned the efficacy of such pledges, but a 2008 study by the RAND Corporation showed that those adolescents who committed themselves to virginity oaths “were less likely to be sexually active over the three-year study period than other youth who were similar to them, but who did not make a virginity pledge.”

KEEPING THE FAITH

During the heralded New Age of the Beatles generation (“We’re more popular than Jesus now”), various celebrities and influential intellectuals pronounced the death of old-style American religiosity and trumpeted its replacement with assorted cults, fads, and crackpots. Time magazine ran a cover story in 1966 that featured a black background with red lettering boldly asking, “Is God Dead?” A generation later, a comparison of church attendance and magazine circulation figures suggests that the Almighty may possess considerably more vitality than Time itself.

The United States remains an incurably God-centered society, with levels of belief and participation dramatically higher than in Western Europe. British journalist Geoffrey Wheatcroft in the Wall Street Journal reported regular attendance at religious services in the United Kingdom at 7 percent, and a pathetic 2 percent for the official Church of England. The lowest comparable figures for the United States, as Professor Robert Wuthnow of Princeton has noted, range between 30 and 35 percent of the adult population.

Meanwhile, the Gallup Organization offers its own “Index of Leading Religious Indicators,” measuring a variety of variables: belief in God, the importance of religion in lives, membership in churches, weekly worship attendance, confidence in organized religion, confidence in ethics of clergy, and relevance of religion in today’s society. Gathering data on these issues going back to 1941, Gallup (like other surveys) shows 1957–58 as a peak year for religiosity, followed by precipitous declines, then another rise between 1977 and 1985. After a thirty-point decline between the Reagan era and the middle of the Clinton era (1996), religion resumed its upward march, with a twenty-point rise in the past ten years.

The most demanding and scripturally rigorous denominations show the greatest vitality of all. Professor Wuthnow, generally skeptical of all talk of a religious revival, unequivocally acknowledges the swelling influence of conservative forces in scriptural interpretation:

First, as a proportion of the entire U.S. public, evangelical Protestant affiliation grew from around 17 to 20 percent in the early 1970s to between 25 and 28 percent in more recent surveys. Second, because the affiliation with the more liberal or moderate mainline Protestant denominations was declining during this period, the relative strength of conservative Protestantism was even more evident. For example, conservative Protestantism had been only about two-thirds as prominent as mainline Protestantism in the early 1970s but outstripped it by a margin of 2 to 1 in some of the more recent surveys.

The chief growth in religious commitment, in other words, has come in precisely those strict and enthusiastic denominations (evangelical Christianity, Mormonism, traditional Catholicism, Orthodox Judaism) that provide the structure and the communal institutions to connect personal faith to the broader regeneration of social capital and functional values.

Francis Fukuyama notes that the current vitality of religious institutions confounds all expectations of the past:

A generation or two ago, social scientists generally believed secularization was the inevitable byproduct of modernization, but in the United States and many other advanced societies, religion does not seem to be in danger of dying out.

He sees the reconnection to religious institutions as motivated more by rational self-interest than by selfless faith:

Religion may serve a purpose in reestablishing norms, even without a sudden return to religious orthodoxy. Religion is frequently not so much the product of dogmatic belief as it is the provider of a convenient language that allows communities to express moral beliefs that they would hold on entirely secular grounds. . . . In countless ways, modern, educated, skeptical people are drawn to religion because it offers them community, ritual, and support for values they otherwise hold.

In his view, religion may be an instrument for the revitalization of values rather than the driving force behind it, but the connection between faith and cultural revival remains indispensable.

ENDORSING DEGENERACY

While faith-based communities constitute a potent factor in remoralization, they face a uniquely powerful opposing force in today’s society: the influence of mass media and the arts.

In the past, few authority figures glorified radical challenges to the established ethical order. In Hogarth’s eighteenth-century London, many residents of every rank and station drank to excess, abused or abandoned their families, frequented houses of ill fame, contracted grotesque and incurable diseases, and then collapsed as pustulating refuse among the foraging pigs in the fetid and rubbish-ridden streets. At the time, however, no novelists or musicians or pamphleteers troubled to celebrate such behavior or to hail the miscreants as courageous avatars of some new consciousness. In previous generations, even at moments of thoroughgoing moral breakdown, the attitude of leading institutions remained sternly disapproving. Corruption might infect the church, the government, the aristocracy, the press, and the universities, but none of these official establishments ever attempted to endorse degeneracy.

Today, on the other hand, Yale and other elite institutions host “sex fairs” for undergraduates to learn about the diverse joys of group sex, transvestitism, bestiality, masochism, and even necrophilia. Legislatures in several states have passed laws making it illegal to “discriminate” against behaviors classified as felonious just one generation ago. Cable television and satellite radio offer prurient material every day and, in fact, every hour that would have provoked prosecution for obscenity in an earlier age.

The obstacles to a sweeping restoration of values remain ubiquitous and overwhelming. Any effort to roll back immorality faces formidable government bureaucracies, official regulations, the smug assurance of nearly all of academia, and ceaseless special pleading in mass media meant to protect and glamorize the most deeply dysfunctional values.

THE POWER OF CHOICE

In 1992, I decried the corrosive impact of media’s visceral hostility to faith and family in my controversial book Hollywood vs. America:

The dream factory has become the poison factory. Hollywood ignores the concerns of the overwhelming majority of the American people who worry over the destructive messages so frequently featured in today’s movies, television, and popular music. . . . It’s not “mediocrity and escapism” that leave audiences cold, but sleaze and self-indulgence. What troubles people about the popular culture isn’t the competence with which it’s shaped, but the messages it sends, the view of the world it transmits. Hollywood no longer reflects—or even respects—the values of most American families.

Considering the current caliber of offerings from the entertainment conglomerates, it’s difficult to discern evidence of redemption that would require a revision of this verdict. It’s true that big studio films and network TV have somewhat deemphasized the exploitation of graphic violence, but the salacious focus on bodily functions and witless, joyless raunch continues to typify an industry once considered the international arbiter of glamour and class.

Even without literally hundreds of readily available university studies to make the point, the influence of popular culture remains potent and inescapable, especially in light of the fact that the average American views twenty-nine hours of TV weekly (without calculating the many additional hours of DVDs, video games, theatrical films, the Internet, and pop music). Given this prominence of media distractions in our lives, the question for the nation’s moral health becomes obvious: how could the public provide significant evidence of reformation and restoration when the most prominent and popular entertainment offerings continue to drag consumers in the opposite direction?

The answer provides both encouragement for the present and hope for the future, and centers on the single word choice.

L. Gordon Crovitz, former publisher of the Wall Street Journal, effectively sums up the most positive and dynamic aspects of our cultural landscape. “Technologists are optimists, for good reason,” he writes. “My own bias is that as information becomes more accessible, individuals gain choice, control and freedom.”

The one great improvement in our media and even educational landscape involves the proliferation of unprecedented alternatives, often tied to new technologies. With cable and satellite and Internet options, the nation has become less dependent than ever before on the dreary array of network programming. Not only do neighborhood video stores provide literally thousands of DVDs delivering the best (and worst) offerings in Hollywood history, but they do so with the addition of exclusive (and often educational) features never seen in theaters. The Internet, with literally countless diversions and downloads on offer, lends its own unimaginable power to breaking the tyranny of film company bosses and network programmers.

A restless and disillusioned public can’t, in the end, control the release schedule of any major studio, but each consumer can shape the schedule of what he chooses to see. Beleaguered families won’t succeed in determining the new fall lineup of any TV network, but they get the final say in what they decide to watch.

With the help of the information revolution and dramatic improvements in communication, Americans have developed their own networks and affinity groups and subcultures, largely independent of bureaucratic or corporate control. In Milton Friedman’s famous phrase, we are now “free to choose” and to defy the overwhelming forces that purportedly drove society only in a downward direction.

This new freedom even facilitates the basic approach advocated by Paul Weyrich in his despairing “we have lost the culture war” letter of 1999. “Therefore,” he wrote, “what seems to me a legitimate strategy for us to follow is to look at ways to separate ourselves from the institutions that have been captured by the ideology of Political Correctness, or by other enemies of our traditional culture . . . I think that we have to look at a whole series of possibilities for bypassing the institutions that are controlled by the enemy.” The rapid development of home schooling, with practitioners gaining unprecedented access to curricula and expertise through the Internet, provides one example of bottom-up expressions of do-it-yourself conservatism that already play a role in the ongoing revival.

The power of choice and the exercise of free will can inject wholesome energy into a troubled society and begin the process of regeneration, but the decentralization and, ultimately, democratization of decisions and authority make it unthinkable to return to an era of unquestioned, top-down moral absolutes. As Fukuyama writes:

What would the remoralization of society look like? In some of its manifestations, it would represent a continuation of trends that have already occurred in the 1990s, such as the return of middleclass people from their gated suburban communities to downtown areas, where a renewed sense of order and civility once again makes them feel secure enough to live and work. It would show up in increasing levels of participation in civil associations and political engagement.

The predicted surge in political engagement constituted one of the most notable aspects of the campaign year 2008. But Fukuyama cautions that the improvement in the moral climate can only go so far:

Strict Victorian rules concerning sex are very unlikely to return. Unless someone can figure out a way to un-invent birth control, or move women out of the labor force, the nuclear family of the 1950s is not likely to be reconstituted in anything like its original form. Yet the social role of fathers has proved very plastic from society to society and over time, and it is not unreasonable to think that the commitment of men to their families can be substantially strengthened.

Of course, fathers must choose to change. As David Brooks writes in response to Fukuyama’s arguments: “But why, then, have so many of these social indicators turned around (if only slightly in some cases) over the past few years? The answer is that human beings are not merely victims of forces larger than ourselves. We respond. We respond by instinct and by reason.”

For those who believe it’s already too late, that the nation’s slide to degeneracy has proceeded so far that any meaningful rescue becomes impossible, Brooks suggests that the relevant choice would be to turn off the alarming TV news and walk out the front door. “Our cultural pessimists need some fresh air,” he wrote, memorably, in Policy Review. “They should try wandering around any middle class suburb in the nation, losing themselves amid the cul-de-sacs, the azaleas, the Jeep Cherokees, the neat lawns, the Little Tikes kiddie cars, and the height-adjustable basketball backboards. Is this really what cultural collapse would look like? . . . The evidence of our eyes, ears, and senses is that America is not a moral wasteland. It is, instead, a tranquil place, perhaps not one that elevates mankind to its highest glory, but doing reasonably well, all things considered.”

THE KIDS ARE ALL RIGHT

The children of those cul-de-sacs Brooks describes have already begun to surprise the declinists with their improved performance in school (with the National Assessment of Educational Progress reporting steady progress among fourth graders in both math and reading, and with the mean SAT score eight points higher in the twelve years after 1993) and with their reduced rates of drug use, alcohol abuse, smoking, criminal violence, and sexual adventurism. John P. Walters, director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, succinctly characterized the wide-ranging and encouraging changes: “We have a broad set of behaviors by young people that are going in a healthy direction.”

This phenomenon has also produced an increasingly common if unexpected generational contrast: young people (and especially young couples) who embrace a more fervent and rigorous religiosity than their parents or grandparents. The clichéd melodramas in the ancient style of The Jazz Singer (1927)—where a youthful, assimilated, show-business-crazy American rejects the pious immigrant orthodoxy of his parents—have given way to distinctive twenty-first-century tales of a new generation renouncing pallid secularism and rediscovering long-forgotten traditions. USA Today reported on this new pattern and indicated that “clergy of all stripes say they are seeing a small wave of young adults who are more pious than their parents. And they’re getting an earful from boomer moms and dads who range from shocked to delighted.”

In other words, religiously as well as morally, Americans refuse to march along a single parade route, even as we find ourselves unable to stand still. All measures of morality show a complex, multifaceted, and, to some extent, turbulent nation. Some Americans (unfortunately concentrated in the media, academia, and other centers of influence) explore decadence and experimental values with more daring or abandon than ever before. At the same time, many others flock to churches and synagogues (where religious services regularly draw four times more participants than all feature films every weekend) and affirm faith-filled values with passion, self-confidence, and dedication that continue to energize the religious conservative movement.

This contribution has already renewed the pro-life cause. Wehner and Levin write: “All in all, not only has the public discussion of abortion been profoundly transformed, but younger Americans seem to have moved the farthest—in September [2007], a Harris poll found that Americans aged eighteen to thirty were the most likely of all age groups to oppose the practice. This trend seems likely to continue.”

Wehner and Levin conclude: “In attitudes toward education, drugs, abortion, religion, marriage, and divorce, the current generation of teenagers and young adults appears in many respects to be more culturally conservative than its immediate predecessors. To any who may have written off American society as incorrigibly corrupt and adrift, these young people offer a powerful reminder of the boundless inner resources still at our disposal, and of our constantly surprising national resilience.”

Even those young people who may take their time in finding their way cannot be counted as irredeemably lost. As Walter Olson wrote in Reason magazine: “Individually, most adolescents who act out do not proceed in a straight line ever downward to crash in early romantic deaths. Something causes most of them to readjust their time horizons in search of longer-term satisfactions, in the mysterious process known as growing up. The thesis of cultural declinists must be that the process of unforced improvement and learning we see take place in individuals all the time couldn’t possibly take place writ large.”

For society as well as individuals, no passage is final: lifelong skeptics and cynics may embrace biblical truth in their seventies or eighties (as in the controversial case of the British atheist professor Antony Flew), or prominent religious leaders, especially when tainted by scandal or tagged with hypocrisy, may walk away from the faith of a lifetime. Choice remains an option, both nationally and personally—even if you believe that the choice rests ultimately with the Higher Power who directs our ends.

Moreover, in the United States no family story concludes with a single generation. Those raised in strictly religious homes will, on famous occasions, throw over the faith of their fathers with an angry and dismissive attitude. More frequently today, children of unchurched parents will become religious leaders or teachers, and pillars of conventional morality—and even go home to recruit various siblings or elders to the cause of renewal.

No matter how zealous their religiosity, however, these young believers won’t take to the streets as wild-eyed prophets of onrushing apocalypse. In all my years of travel to every major city in the country, I’ve encountered plenty of hirsute hobos but never saw one who actually packed a placard proclaiming THE END IS NEAR. These figures of fantasy fit best in cartoons, since the real nation is focused more fervently on beginnings.

America remains, as always and in all things, on the move. Those who have already written off this great and good society as the victim of unstoppable degeneracy don’t understand the eternal national capacity for fresh starts and new life.