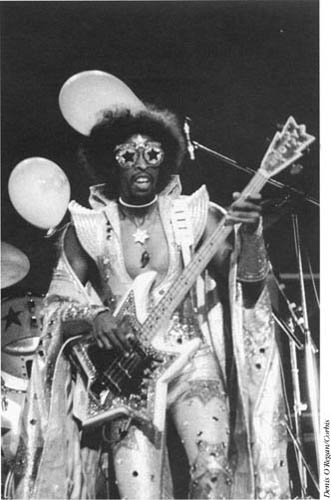

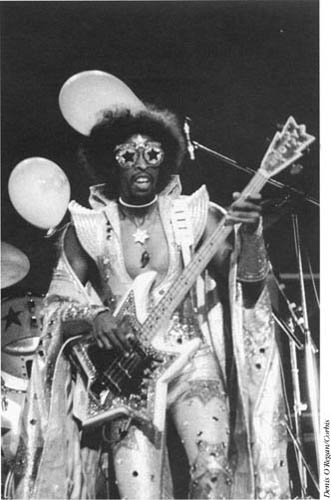

Bass player Bootsy Collins was in the forefront of George Clinton’s 1970s group Funkadelic, which became the model of funk and musically influenced soul, rock, jazz, and rap.

The tight blasts of horn riffs, the off-kilter bass line, the chugging rhythm guitar break, the wild vocal about the “new breed thang,” and most of all, the beat: it is unusual that a musical genre’s birth can be crystallised within the time frame of a single song, but that is the case with funk.

James BROWN had hinted at a new direction with his pulsing 1964 single “Out of Sight.” But “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag,” released in July 1965, declared Brown’s new discovery outright. With “Bag,” Brown accentuated the first and third beats of a four-beat measure, as opposed to the classic shuffle beat’s emphasis on the second and fourth, and crafted an arrangement that emphasised this, “playing” his band as if it was a drum kit. Brown’s ensemble featured some outstanding and open-minded musicians, players who could breathe life into the new sound that Brown heard in his head. The finished product—two minutes and six seconds of tight, spine-tingling groove—was an undeniable declaration that something startlingly new had indeed occurred.

Brown’s polyrhythmic innovation—“funk,” as it came to be called—represented a radical re-invention of popular music that emphasised the beat as the supreme element of a song. Fred Wesley, a trombone player for Brown’s own band, offered this description: “If you have a syncopated bass line, a strong, strong, heavy back beat from the drummer, a counter-line from the guitar or the keyboard, and someone soul-singing on top of that in a gospel style, then you have funk.”

The name “funk,” which comes from an Old English term meaning strong smell, even serves as a vivid description of this energetic, uninhibited, and extremely danceable music. In particular, the olfactory sense of the word can be seen in the way funk is undeniably rife with sexuality. At the same time, the lyrical content de-emphasised the traditional “love” song approach, instead using the invigorating and liberating power of rhythm as a new platform for black American voices. In the light of its subsequent effect on rock, jazz, and rap, funk should be recognised as one of the most significant musical movements of the latter half of the 20th century.

Bass player Bootsy Collins was in the forefront of George Clinton’s 1970s group Funkadelic, which became the model of funk and musically influenced soul, rock, jazz, and rap.

Not long after Brown unleashed “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” on the world, the Southern soul studios of Stax in Memphis, and Fame in Muscle Shoals, Tennessee (and later, at MOTOWN in Detroit), were weaving Brown’s exciting new rhythms into recordings by artists such as Wilson Pickett, Aretha FRANKLIN, and Otis REDDING. Meanwhile, there emerged a new blend of music, dubbed “jazz-funk,” which inspired such notable jazz players as Miles DAVIS and Herbie HANCOCK to explore its rhythms.

By the time Brown recorded “Cold Sweat” in 1967, he had all but abandoned melody and stripped his music to the core, leaving nothing but exhilarating, visceral groove. “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag,” “Cold Sweat,” along with Brown’s other classic singles of the period—“I Got You (I Feel Good),” “I Got the Feelin’,” “Licking Stick,” “Talkin’ Loud & Sayin’ Nothing,” “Mother Popcorn,” “Soul Power,” “Super Bad,” “Sex Machine,” to name a few—still stand as the sacred original texts of the funk genre.

Despite Brown’s amazing mid-to-late 1960s recordings, only “I Got You (I Feel Good)” ever broke into the top five of the pop charts. Funk’s introduction to mainstream America would come instead from the group Sly and the Family Stone, a wild multi-racial pop/rock/funk group that was a constant presence on the pop charts between 1968 and 1970. Their hit album Stand! and their ferocious performance at the Woodstock festival in 1969, as well as on the film and soundtrack album, finally provided the stage for funk to explode into white consciousness.

Meanwhile, in New Orleans, The Meters were developing a brilliant minimalist groove, mixing the melodic style of Booker T. and the MGs, the funk of James Brown, and the proto-funk of piano virtuoso Professor Longhair. While never attaining the popularity of Sly Stone or Brown, The Meters would rule the groove of what is arguably America’s funkiest city, as well as greatly influence many other Southern funk musicians. Their performance on LaBelle’s “Lady Marmalade” stands as one of the finest moments of 1970s funk.

Funk dominated black musical styles throughout the decade of the 1970s. Established soul artists such as Marvin GAYE, Stevie WONDER, and the Temptations latched on to the new groove, which took them to new artistic and commercial heights. A new generation of soul-funk groups, such as Kool & the Gang, the O’Jays, and Earth, Wind & Fire, appeared on the scene, selling records in the millions. Other groups followed Sly Stone’s genre-busting lead, including the Bar-Kays, the Isley Brothers, War, and the Ohio Players—all of whom aimed to break down the walls between funk and rock, making records that sold to both audiences.

Funk’s supreme ruler during the 1970s was singer George Clinton. He and the P-Funk empire recorded and released nearly 30 albums of funk between 1970 and 1981, with one outrageous dance band (Parliament) playing James Brown-like, horn-driven funk, and another even more eccentric funk-rock band (Funkadelic) echoing the psychedelia of the BEATLES and guitar freak-outs of Jimi Hendrix, in addition to a huge, loose collective of innovative musicians (including Fred Wesley, saxophonist Maceo Parker, and bassist Bootsy Collins from James Brown’s band). Clinton’s and P-Funk’s inspired insanity, from the sinuous rhythms and outrageous lyrics to the orgiastic sense of visual presentation, set the standard for funk.

Toward the middle of the 1970s, disco began to emerge. Borrowing funk’s idea of rhythmic syncopation, it employed slick, synthesized production techniques rather than the natural “feel” of live musicians. This inevitably resulted in a sterilised, homogenised groove and a thinner sound. Disco may have been a pale imitation of funk, but its overnight fall from grace at the end of the 1970s unfortunately dragged down funk’s stature as well.

Post-disco artists such as Rick James and PRINCE managed to restore funk to favour during the 1980s, but by then rap had already asserted itself as the cutting edge in African-American music. And while rap could never have existed without the hard beats it had adopted from funk, it is arguable that rap’s reliance on the use of digital sampling detracts from its musical (and human) “feel.” Those very samples have, however, turned a younger generation on to some of the classic grooves of Brown and Clinton. Through its distinctive feel, funk continues in its role as a catalyst for inspired musical innovation.

Greg Bower

SEE ALSO:

DISCO; JAZZ; RAP; ROCK MUSIC; SOUL.

Marsh, Dave. George Clinton and P-Funk:

An Oral History (New York: Avon, 1998);

Vincent, Rickey. Funk: The Music, the People,

and the Rhythm of the One

(New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1996).

James Brown: Star Time (4-CD set);

Parliament: Give up the Funk;

Sly and the Family Stone: Dance to the Music.