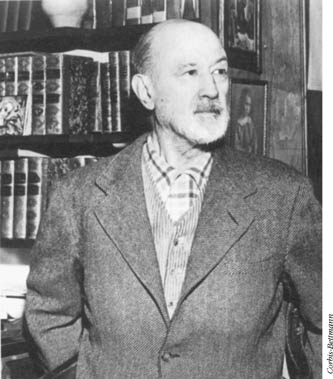

Charles Ives initiated the development of American music free from the constraints of the European tradition.

Pioneer American composer Charles Ives was the first major figure in concert music to be educated entirely in the U.S., and the first to advocate the need for an American music free from European influences. The extraordinary, if often somewhat brash, originality of his music continues to astound audiences long after it was written.

Ives’s innovative, musically rebellious spirit was inherited from his father, George Ives (1845–94) who had been a bandmaster in the American Civil War. After the war he settled in the small manufacturing city of Danbury, Connecticut, where he led a local band and a church choir, and taught music in nearby schools. George Ives’s experimentation with musical forms was highly unorthodox for his time. For example, music lessons for “Charlie,” born October 20, 1874, included getting his son to sing a tune in one key while George played the accompaniment in another. In the most famous of his experiments, George Ives arranged to have two brass bands marching along opposite sides of the town green, playing different tunes and finally merging in a fearsome cacophony.

By the time 20-year-old Charles began his formal musical training at Yale, his father’s influence had prepared him to question the status quo, and he soon earned the wrath of Yale’s conservative music faculty, especially that of his formidable tutor, Horatio Parker. George Ives encouraged his son to stand up to Parker—when the latter complained about a certain unresolved ninth in one of Ives’s compositions, George wrote to Charles: “Tell Parker that every dissonance doesn’t have to resolve, if it doesn’t happen to feel like it, any more than every horse should have its tail bobbed just because it’s the prevailing fashion.” In November 1894, George Ives died suddenly; Charles, however, continued to be faithful to his father’s spirit.

In 1887, Ives produced his long, rambling Symphony No. 1, which committed what was at the time one of the deadliest of musical sins—it began in one key and ended in another. Another student work, the string quartet subtitled “A Revival Service,” consisted mostly of American hymn tunes culled from boyhood memories, and subjected in places to some highly irreligious contrapuntal treatment, including the subversive notion of two tunes played simultaneously, simply smashed against one another. This, too, fell upon deaf ears within the university walls.

Charles Ives initiated the development of American music free from the constraints of the European tradition.

In 1898, Ives moved to New York City and accepted a post with the Mutual insurance company. It was a fortunate move—for the rest of his life, Ives’s insurance career supported him handsomely, and left him enough free time to pursue music at his own pace, although the demands of doing both took a toll on his health. By 1900, he was spending his weekends as organist at New York’s prestigious Central Presbyterian Church, where his improvised reharmonisations of old hymns outraged some, but delighted others. Nearly all Ives’s musical legacy was created in the 15 years from 1898 to 1913; an astounding series of works that would have to wait at least another 40 years before public performance.

In 1908, after a long courtship, Ives married Harmony Twichell. Three years later, they bought a farmhouse some miles to the north. Ives continued to pursue his insurance career on weekdays, eventually founding his own company. On weekends, Ives served as organist in several churches, but spent most of his time writing a repertory of orchestral works, chamber music, piano pieces, choruses, and songs.

Ives’s varied compositions explored everything that stirred his intensely American consciousness— American music, poetry, and prose, the urban and rural landscape, and the example of 19th-century artistic revolutionaries such as the writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. The memory of his father’s musical experiment with the two brass bands lingered in the 1908 suite, Three Places in New England, and in a tone-poem called Central Park in the Dark (1906), where the sounds of several groups of musicmakers seem to reach the audience from afar. He also responded to contemporary events and personalities. His outrage at the German invasion of Belgium in 1914 provoked his chorus “Sneak Thief,” while the third movement of Orchestral Set No. 2 was inspired by the sinking of the Lusitania off Ireland in May 1915.

The notion of musical space fascinated Ives. In a short, now well-known, work called The Unanswered Question (1906), the various orchestral groups are placed at remote points in the auditorium: onstage strings sound soft chords; an offstage trumpet proposes “the perennial Question of Existence,” and “flutes and other persons” move around as “the Flying Answerers.”

Despite his often scathing views on the European classical and Romantic repertory (“music for old ladies of both sexes”), Ives did retain something from his musical forebears, in the titling of some of the larger works: four symphonies, two piano sonatas, four sonatas for violin and piano, and two string quartets. The similarity to European models, however, ended there. In structure, the works were distinctly, even obsessively, American—folk songs, hymns, and dances banged against one another to create frightening dissonances one minute; serene, seraphic visions the next. Ives constantly revised his work, altering the harmonies of decades-old compositions and tilting them in the direction of ever more peppery dissonances and rhythmic complexity.

For most of his life, Ives remained largely unknown to the musical public. However, a breakthrough came in January 1939, when pianist John Kirkpatrick introduced Piano Sonata No. 2 to a sparse New York audience that included distinguished critic Lawrence Gilman. Gilman called the Sonata the “greatest music composed by an American … deeply and essentially American.” Suddenly Ives was in demand. In 1946 alone, New York heard the premieres of Symphony No. 3, Central Park in the Dark, The Unanswered Question, Violin Sonata No. 1, and String Quartet No. 2—all of them composed up to 40 years before.

In 1947, the Pulitzer Prize in Music was awarded to Ives for his serene Symphony No. 3. Ives was 73, virtually paralysed by a series of heart attacks over the years, ill-tempered, and nearly blind. He had stopped composing 25 years earlier when he felt that his creativity had deserted him, and, to his credit, he handed over the prize money to another composer he deemed in greater need. As his fame finally grew, he seemed to want no part of it, wearing his bitterness with some pride. As a small concession, he consented to hear Leonard BERNSTEIN’S broadcast of the premiere of Symphony No. 2—in 1951, 53 years after its creation. In May 1954, Ives died due to a stroke.

Ives’s volcanically energetic music stands as a synthesis of the American creative spirit: the rough-cut emotions of Whitman’s lyric poetry, the mysticism of Thoreau, and the same love of the land that powered the brushes of the Hudson River School of painting.

Alan Rich

SEE ALSO:

CARTER, ELLIOTT; COPLAND, AARON; ORCHESTRAL MUSIC

FURTHER READING

Burckholder, J. Peter. Charles Ives and His World (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996);

Lambert, Philip. The Music of Charles Ives (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997);

Swafford, Jan. Charles Ives: A life with Music (London: W. W. Norton, 1996).

SUGGESTED LISTENING

Central Park in the Dark; Concord Sonata for Piano; Five Violin Sonatas;

New England Holidays: A Symphony, Symphony No. 3; The Unanswered Question.