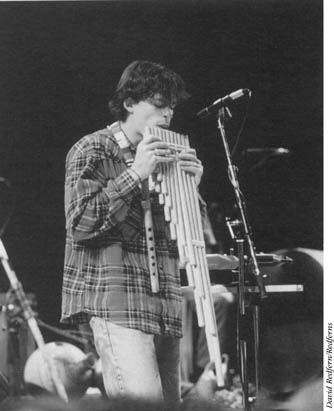

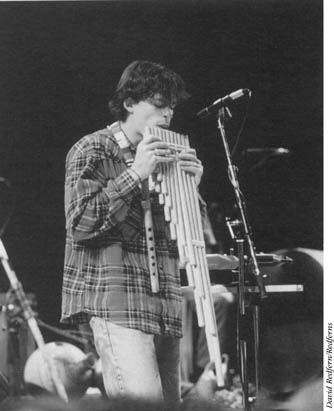

Panpipes are found in many parts of the world, but the most familiar are those from the Andes. They are made of graduated pipes, and played by blowing across the top.

The sounds of Latin America cover an enormous range, reflecting the history and size of the region (here taken to be all Portuguese- and Spanish-speaking countries from Mexico southwards through Central and South America and including Cuba). In many parts of the South American continent, such as the Amazon and the Andes, the indigenous peoples have had limited contact with the rest of the population, and so some very primitive forms of music survive. But the region has been invaded in many ways over the centuries: by the Spanish and the Portuguese in the 16th century; by slaves imported from West Africa; and by influxes of immigrants from Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Western classical music was first brought to the region by the Spanish and Portuguese, often Jesuit priests who came with the earliest European settlers, and the music of the Catholic Church still uses texts and sounds from that era. In the early part of the 20th century, Latin America remained somewhat isolated from Western cultural influences, but later some musicians arrived fleeing from persecution by communist or fascist regimes. Pop and rock music has similarly been relatively slow to develop, but is now to be heard almost throughout Latin America.

On the other hand, various popular forms from South America have spread to Europe and the U.S. These include the samba and bossa nova from Brazil, and the tango from Argentina. And, in the later years of the 20th century, Andean music and Colombia’s infectious cumbia have been heard around the world. (The music of Cuba, Mexico, Venezuela, the Andes, and Brazil is covered in greater detail in their respective entries elsewhere in this encyclopedia.)

The indigenous Indian population of Cuba was virtually wiped out by the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores in the 16th century. Once settled, the Spanish imported slaves from West Africa, who in turn have had the greatest influence on modern Cuban music. Today, song and dance are inseparable in Cuba and feature in all aspects of the island’s life. The musical instruments are also allied to African instruments, with the addition of variants on the ubiquitous Spanish guitar. These instruments include the güiro, which is a gourd with raised frets that are rubbed with a stick; the claves, which are hard polished sticks that are tapped together; and the many different types of drum, including the bongos and the larger tumbadora.

The popular dances of the island—including the danzon, the rumba, the conga, the mambo, and the son —tend to be dramatic, often acted out with a story sung with improvised topical additions. There is also some surviving ritual music using drums that accompany religious ceremonies.

There has also been a strong tradition of European-influenced classical music since the 18th century, when Havana Cathedral became the centre for opera and symphonic music as well as church music. The Cuban novelist, poet, and musicologist Alejo Carpentier discovered and revived some of this Baroque musical treasure, and the composer Alejandro Caturla (1906–40) set to music some of Carpentier’s poetry and used other folk elements in his “Afrocubanismo” orchestral works.

Perhaps the best-known Cuban composer of concert music is Leo Brouwer (b. 1939). His works for guitar are part of the classical repertoire, including the famous El decameron negro, but he has also experimented with the avant-garde techniques of serialism, electronic tapes, and prepared piano (wedging objects between a piano’s strings to produce an unusual array of sounds).

Mexico, the only Latin American country sharing a border with the United States, also shares a genre of music known as norteño (“Tex-Mex” in America). Norteño is accompanied by accordion, and is popular for its topical ballads called corridos. But the most famous style of Mexican music is the mariachi, with its bands sporting highly decorated uniforms and huge sombreros. These mariachi bands perform romantic or regionally nostalgic songs sung with theatrical exaggeration and supported by the blare of trumpets and the thump of a huge handheld acoustic guitar called the guitarrón. A far more delicate musical genre based around the harp and called huapango is found further south, in central Mexico and close to the Gulf Coast.

The nations of Central America borrow heavily from the music of Mexico to the north, Colombia to the south, and the Caribbean Islands to the east, and, in the case of Nicaragua, from the politically motivated nueva canción (new song) movement. In addition, some traces of the ancient Mayan culture can still be found in Nicaragua and Belize, and more strongly in Guatemala. Indians of Mayan origin form about half of the population of Guatemala. Their cultural heritage has been preserved to an extraordinary extent because of their great reverence for their mythology and rituals. Their instruments include various slit-drums, gongs, and rattles, and cane flutes that sometimes have the rattles of rattlesnakes enclosed in a hollow above the embouchure. This is then closed off with a thin membrane, and the resulting menacing buzz is heard in the baile de venada (dance of the deer).

Side by side with the Indian tradition in Guatemala is the equally thriving music of the Ladino population, which is Hispanic in origin and is found mostly in urban centres. But the instrument that is central to Ladino music, the marimba de tecomates —which has a keyboard of wooden bars with gourds suspended underneath—is thought to be of African origin. Although Ladino groups have now adopted more modern marimbas, there is still a great variety among them. The largest, the marimba grande, has a range similar to a piano and is played by four players.

The son guatemalteco is the national dance of Guatemala, and dancers bring out the son rhythm with zapateadas or foot stamping. These indigenous rhythms and themes have also been incorporated into classical music. The brothers Jesús and Ricardo Castillo were Guatemalan classical composers of the first half of the 20th century. Jesús wrote a treatise on the Mayan music of the country, and both brothers wrote pieces using Indian themes (Suites indigenas) and even operas (Quiché Vinak). In Nicaragua, Luis Delgadillo (1887–1962) also included Inca themes as well as other indigenous Nicaraguan music in his work. His suite Teotihuacán, on the other hand, explores themes from Mexico to the north.

The furthest south of the Central American countries, Panama, was formerly part of Colombia until 1903, and is said by some to be the source of that country’s cumbia. Its musical traditions are a mix of Spanish, Indian, and African, but as one of the most cosmopolitan countries of the region, folk music is now mainly the preserve of schools and folklore societies.

Panpipes are found in many parts of the world, but the most familiar are those from the Andes. They are made of graduated pipes, and played by blowing across the top.

There are many traces of Spanish influence in Panama’s music, including the beautifully costumed tamborito dance, which features a female singer and drums, and is considered a national trademark. The black population along the northern coast, of Caribbean origin, has the congo, its o w n version of the tamborito, in which the dance movements are more obviously erotic. The punto is by contrast stately and slow, accompanied by violin, guitar, flute, and drums.

The most well-known musician Panama has produced is undoubtedly Rubén BLADES, whose blend of politically committed nueva canción and salsa has won him a worldwide audience.

Well inland from the Atlantic coast of Colombia—home of the country’s predominant dance form, cumbia—are remote rainforests where melodies of the “old country” (Spain) are preserved. The Colombian alabaos and salves, for example, are of Spanish religious origin and are still used during funerals and wakes. European dance forms preserved by blacks in rural Colombia include the contradanza, polka, and jota. The village fiesta bands called porros, found in the provinces between the coast and the capital, Bogota, are modelled on European military bands and are often as roughshod as they are competitive and loud.

The stringed instruments in northern South America are derived from Spanish models, including a variety of guitars, like the cuatro (four), named for their varying number of strings, and the mandolinlike bandola. There are also varieties of folk harp throughout Colombia and Venezuela, and in the rest of South America.

The harp predominates in the music of the llaneros (cowboys) from Colombia’s Atlantic littoral and the plains regions of Venezuela. The music, called llanera, also features the cuatro and bandola along with capachos (maracas), accompanying swinging but relaxed and sentimental songs. Subgenres of llanera include coplas, which are based on Spanish couplet forms and are sung to quiet or to herd the cattle; joropo, which displays the zapateo footwork associated with Spanish dance; and contrapunteos or porfías, sung as musical duels reminiscent of Spanish desafíos.

Other instruments and song forms are derived from West Africa, including the wooden benches, which are played with beaters, the beautifully carved cylinder drums of Surinam, east of Venezuela, and the call-and-response religious and festival music of Venezuela’s blacks. Marimbas on the Pacific littoral of Colombia are played by two players and accompany, with drums and percussion, a courting dance of African origin. The currulao from this area is characterised by interlocking rhythms and layered vocals remarkably evocative of West Africa.

An interesting and unique form of syncretism—the blending of different belief systems—can be found in the Guinea Highlands of Venezuela and Guyana. A religious cult there known as Hallelujah uses vintage Irish and Scottish songs for its liturgical music. However, it arranges them in descending modes typical of indigenous Amerindian music. The songs and dances are coordinated by a shaman-like leader. In more remote mountainous pockets, Ika Indians, the original cultivators of coca, still play their indigenous flutes and rattles.

Equally fascinating is vallenato, which supposedly took its name from the town of Valledupar near the heart of the activity on the Atlantic coast, and was first developed by an accordionist called Francisco el Hombre. The basic conjunto includes accordion, a caja vallenata drum, and a guacharaca scraper, but more modern groups have added extra percussion and electric bass. The bass player may develop idiosyncratic lines (as in reggae) under the accordion’s loud, decorative solos and riffs (the accordionist also serves as leader and singer).

The music and peoples of the northern Andean countries can be roughly divided into highland and lowland regions. The Indian communities tend to be i n the mountains, and the Creole and mestizo (mixed race) population in the valleys. The Indian peoples can be further divided into the aboriginal tribes and the Quechua, who are descended from the Incas. In the forests of the Peruvian mountains, there are over 30 tribes of Indians, still hunter-gatherers, some of whom are little known outside the region. Their music is used for tribal rites, for fertility, for initiation ceremonies, and to hand down the mythology of their people.

The Quechua are a more settled people with a highly developed agriculture of terraces and irrigation channels on the steep mountainsides. It is their music that has given Peru its national dance and song form, the huayno, a lively scarf dance accompanied by foot stamping.

The folk instruments of the northern Andes, including the panpipes, the notched flute (the quend), harp, and various rattles and drums, are common to the Amerindians of Peru, Bolivia, and northern Chile. The indigenous Indians of Peru also play various forms of ocarina and musical bow.

During the 20th century, however, there have been increasing migrations of Andeans to the cities, and their music has inevitably merged with other genres. The marinera, as its name suggests, has its origin on the coast, though it is sometimes recorded and performed in combination with Andean huaynos. It is a flirtatious dance popular at festivals and in middle-class clubs in Lima. Muliza bears traces of Andean melody, and may be performed by musical ensembles of harp, fiddle, clarinets, and saxophones, but the arrangements and attitude of the singers suggest a theatricality imported f r om Europe; Spanish influence is specifically evident in the footwork. Chicha music may be said to have fermented in the early 1960s—its name comes from a popular beer brewed from maize—as a mixture of huayno with the imported sounds of Colombia cumbia and American rock. Its creation, like several other Peruvian forms, followed the migration of mountain peoples to the cities nearer the coast.

Of much older origin is the vals criolla, which echoes upperclass Spanish operatic and theatrical tastes of the 19th century. Descendants of African slaves brought in during the 17th and 18th centuries contributed the syncopated festejo and alcatraz, and their zamacueca was exported as far south as Argentina and Uruguay, and as far north as California in the days of the G o l d Rush.

Brazil stands apart from the rest of Latin America in its Portuguese language and political history, but not entirely in its music. There are enclaves, for example, in isolated pockets of Brazil’s northeastern sertão, where remnants of the Iberian Renaissance can be found in romances and ballads. Also shared with the rest of the continent is the competitive cantoría song form (found as porfías in Venezuela and the contrapunto in Argentina), and variations on certain instruments, including the small guitar-like cavaquinho, of Iberian origin, and the drums introduced f r om Africa, found in the eastern Brazilian state of Bahia.

Brazil had the largest influx of African slaves of any South American country and many musical forms have their roots in West Africa. African percussion such as the agogo (cowbells) and cuica (talking drum) enliven the several forms of samba, including the topical shouts prepared by the escolas de samba for the giant annual Carnaval parade in Rio de Janeiro. Other musical forms reflect different aspects of its history, however. Melancholy or nostalgia, which has its own word in Portuguese (saudade), is heard in 20th-century song forms such as the choros and some pagodes, which hark back to the sad ballad style from o ld Portugal, k n o w n as fado.

A regional music that has only recently been heard abroad is the forro, led by a chugging accordion with roots in the sertão. Connections with the Caribbean further north gave way to the reggae-influenced lambada. Following the wistful and melodic form of samba called bossa nova, which spread to the U.S. and Europe in the 1960s, came the música popular brasiliera (MPB) and tropicalismo movements. These drew on regional styles and American rock as well as on bossa, and gave a voice to a new generation of Brazilian activists and artists. Indeed, political activism has become a central strand in Brazilian popular music. Caetano VELOSO, Chico Buarque, and Milton Nascimento have all been deeply involved in political issues, from combatting corruption to championing Indian rights.

The most important figure in Brazilian classical music is Heitor VILLA-LOBOS (1887–1959) whose enthusiasm for folk music led to the composition of many pieces using local forms and sounds (heard for example in the Bachianas Brasileiras). Another eminent Brazilian composer whose music has reached a wider audience is Ernesto Nazareth (1863–1934). Nazareth was a pianist and composer for the piano and his tangos and polkas, reminiscent of Chopin but redolent with Brazilian style, have remained popular with pianists.

Chile’s geographical position made it relatively isolated until the 20th century. But, because the country does not have the large tracts of relatively undeveloped land that ensure the survival of native tribes, Amerindian music has survived only in small pockets dotted around Chile. Nor was there any significant influx of African slave labour, so the Hispanic tradition remained the chief musical genre until well into the 19th century.

The richest vein of Amerindian music is found in the northern part of the country, where it is contiguous with Peru and Bolivia. The people share the same types of instruments, predominantly woodwind—panpipes and flutes, accompanied by double-headed drums. In addition, the Indians developed their own stringed instruments in imitation of the Spanish invaders—thus, the charango is a small guitar-like instrument made from an armadillo shell. The music uses pentatonic scales, like so much folk music, and is played at festivals and ceremonies.

An even less well-known tradition survives in the far south among the Mapuche and the Fuegian tribes. This music is used for shamanist rites, for fertility or medical purposes, and consists of sung invocations accompanied by rattles and primitive trumpets.

Hispanic music in Chile has retained some archaic characteristics, probably explained by its relative geographical isolation. Some of the music is based on modes, and drones are commonly used as the sustaining element. The ballad form has remained virtually unchanged since it arrived from Spain, but the most characteristic use of this music is in the many folk dance forms that still provide a lively ambience in Chilean festivals. The cueca is considered the national dance and imitates the courtship ritual of a hen and rooster. It is accompanied with clapping and guitar music. The tonada (tune) is the most characteristic folk song, and is sung by women in rural central Chile to the accompaniment of guitar or accordion.

In the latter half of the 20th century, a new music arose as an underground comment on political affairs. This nueva canción movement helped cheer resistance to the dictatorship during the 1960s. One of the best-known figures was Violeta Parra, whose songs took up the cause of the poor and landless. She also joined cause with the poor Amerindians and introduced their music, with its panpipes and charango, to the cities. Although Parra committed suicide in 1967, Victor Jara continued to carry the banner of nueva canción until he was murdered by the military in 1973. One of his songs was banned for naming the minister responsible for a massacre of landless peasants. In 1991, after elections were held, many musicians and dancers gathered in the stadium where Jara was murdered to celebrate the end of the dictatorship with a festival.

In Argentina, the native music shares similarities with that of Chile. The Fuegian Indians survive in the south. In the north, many Indians are immigrant workers from Bolivia and have brought their music and instruments with them. There is also a lively, and largely unadulterated tradition of Creole or mestizo music. Argentina is still a largely rural country, and the gauchos and farm workers often only gather for festivals or Carnaval. Carnaval songs include the vidala and the vidalita accompanied by guitar and drums, and the dances are accompanied by the accordion or sometimes the violin. The gauchos, who are the cowboys of Argentina’s interior pampas, have their own music, milonga, played for their wild, stamping dances in a display of machismo.

The gauchos were also celebrated in an early Argentinean opera. The Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires was founded in 1908 and opera has been a strong tradition in the country ever since. Argentinean opera composers include Felipe Boero whose opera El Matrero uses gaucho dances and songs.

Probably the most important Argentinean composer of the 20th century is Alberto Ginastera (1916–83), whose early work included many pieces of a nationalist orientation, including the Pampeanas. He also went on to write several operas.

Argentina is one of the few South American countries to have gained worldwide attention for one of its musical forms, the tango. The tango is the urban equivalent of the creóle folk dances, the zamba and the gato, and was developed from them and from the melting-pot of immigrants in the slums of Buenos Aires. Its insistent, propulsive rhythms, first played on guitar, violin, and flute—and later led by the large accordion called bandoneón —helped to evolve a stylishly erotic dance that first gained popularity in Buenos Aires clubs and brothels. Beginning in the 1920s, the tango spread to the middle class and eventually into the international dance community in the 1930s. It was rescued from celluloid banality by the recognition, among jazz fans and others, of the considerable composing and playing talent of bandoneón master Astor Piazzolla.

Protest music had a place in Argentina, too. One of the country’s chief popular stars is the dynamic singer Mercedes SOSA, who helped coin the term nueva canción in 1962. Sixteen years later, she was expelled from her country during its period of military repression, but not before she and others had helped to repopularise several indigenous song forms, including the chacarera, zamba, and chamame.

Uruguay has adopted some musical traditions from Argentina and Brazil, and thus includes Spanish and Portuguese idioms. There is no surviving Amerindian music as the last native Uruguayan Indians were exterminated in the 19th century. But there are dance forms that derive from the African slave population, called the comparsas de Carnaval One such, the candombe, is a lively pantomime acted out in procession during Carnaval. The cast includes eccentric characters who have become caricatures—a poor old man with a top hat and a cane, an old fat mother figure, and a broom-maker, who is a sort of demon figure. The performance is accompanied by drumming and songs.

Other Uruguayan folk music of the creóle or mestizo population includes dances and songs accompanied by guitar and drums, and mostly performed by men.

Classical composers in Uruguay during the first half of the 20th century were concerned with the expression of nationalist sentiments. Although many of these composers spent time studying in Europe, their music was not much heard outside Uruguay. The best-known were Eduardo Fabini (1882–1950), whose symphonic tone-poem Campo was a celebration of the Uruguayan landscape, and Luis Cluzeau-Mortet (1889–1957).

Jeff Kaliss

SEE ALSO:

ANDEAN MUSIC; BRAZIL; CARIBBEAN; COLOMBIAN CUMBIA; CUBA; LATIN JAZZ; MEXICO; SALSA; TANGO; VENEZUELA.

FURTHER READING

Béhague, Gerard. Music in Latin America (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1979);

Bergman, Billy, and Andy Schwarz. Hot Sauces: Latin and Caribbean Pop (Poole: Blandford, 1985).

SUGGESTED LISTENING

Argentina and Uruguay

Argentine Folk Songs

Mercedes Sosa: Gracias a la vida.

Brazil

Chico Buarque: Vida; Milton Nascimento: A Arte de Milton Nascimento.

Chile

Antología de Folklore Musical Chileno; Chile Vencerá! An Anthology of Chilean New Song; Violeta Para: Canto a mi America.

Colombia, Venezuela, and the North

Afro-Hispanic Music from Colombia and Ecuador; Harps of Venezuela; Maria Rodriguez: Songs from Venezuela; Songs of the Guiana Jungle.

Cuba, Central America, and Mexico

Afro-Cuba: A Musical Anthology; Rubén Blades: Siembra; Les Celebrations Marimba; Musica Folklorica Panamena.

Peru and Bolivia

Flutes and Strings of the Andes; Mountain Music of Peru.