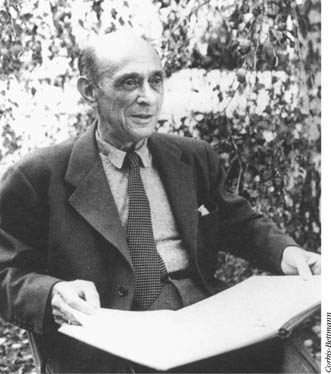

Arnold Schoenberg was one of the most innovative composers of the early 20th century, leaving a profound legacy and transforming the notion of music.

This century’s most controversial composer, Arnold Schoenberg was born in Vienna on September 13, 1874. He began learning the violin at the age of eight and composing little pieces when he was about 12, but he did not decide on music as a career until he was well into his teens. Even then, Schoenberg did not attend a major school or conservatory of music, but studied privately with the composer Alexander Zemlinsky (1871–1942), who was only three years older. Schoenberg is said to have acquired Zemlinsky’s passion for the music of Richard Wagner while studying with him.

Schoenberg married Zemlinsky’s sister, Mathilde, in 1901. They spent two years in Berlin, where he made his living by orchestrating operettas and directing a cabaret orchestra. Mathilde died in 1923, and the following year Schoenberg married Gertrud Kolisch, the sister of the violinist Rudolf Kolisch who championed his music.

Schoenberg’s own early music belongs to the Late Romantic period. Music during this era was dominated by Wagner’s psychological music-dramas, with their rich harmonies and orchestration. Schoenberg’s early works were very much a part of all this: the orchestral piece Verklärte Nacht of 1899; the “monodrama” for singer-actor and orchestra Erwartung of 1909; the orchestral tone poem Pelleas und Melisande; and the massive choral and orchestral cantata, Gurrelieder, finished in 1911. These works are full of feelings of guilt and anxiety, use symbolic images such as moonlight and dark forests, and are deeply influenced by Wagner’s lush and dramatic chromatic and sometimes atonal harmonies.

It was Schoenberg’s growing belief that this kind of post-Wagnerian music had gone as far as it could that made him look for new musical paths to explore. A key work in this process was Schoenberg’s song-cycle Pierrot lunaire of 1912. To capture the dreamlike, sometimes nightmarish imagery of the songs, Schoenberg turned to a not uncommon style of vocal delivery known in German as Sprechstimme (speech song), which hovers between speech and pitched notes. For each of the 21 songs of the cycle, the accompanying chamber ensemble played a different combination of instruments.

Arnold Schoenberg was one of the most innovative composers of the early 20th century, leaving a profound legacy and transforming the notion of music.

Such a style was not entirely new in itself, but Schoenberg’s daring and imaginative use of it in Pierrot lunaire certainly shook the whole artistic world at the time. “If this is music,” wrote one critic who attended the first performance of the song-cycle in Berlin, “Then I pray to my Creator not to let me hear it again.” Schoenberg’s Five Pieces for Orchestra, composed in the same style as Pierrot lunaire, also had its first performance in 1912.

Schoenberg bitterly resented the many attacks on his work, but he would not allow himself to be distracted by them. He soon came to the conclusion that music needed an entirely new kind of “alphabet” or “grammar.” This led him to the momentous decision to abandon entirely the system of 24 major and minor keys and scales that had formed the basis of Western music for hundreds of years. In its place, he based his compositions on “tone-rows” or “note-rows.” This used all 12 notes of the chromatic scale in a particular order that was chosen by the composer. This was Schoenberg’s new system of “dodecaphonic” or “12-tone” composition, also known more generally as “serial” composition, since the “tone-rows” or “note-rows” were played in series.

Serialism was not an entirely new concept: it had appeared in works by Reger and Liszt, but not as the actual basis of composition.

Schoenberg first used this new method of composition in his Five Piano Pieces of 1923. With it, he also divided the musical world between those who were totally baffled by what he was doing and derided it, and those disciples and pupils, notably Anton WEBERN and Alban BBERG, who admired and developed his technique. He also ensured that he would become one of the most influential, and perhaps the most controversial, composers of the century.

While Schoenberg was shaking music to its foundations, events in the outside world were catching up with him. In 1925, he had taken up a major teaching post at the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin. But the arrival of the new Nazi regime quickly made life in Germany impossible for him, not only because he was a Jew, but because his radical ideas were unacceptable to the Nazis.

Schoenberg had converted to Christianity in 1898, but as an act of defiance in the face of Nazi anti-Semitism, he reaffirmed his Jewish faith. This can be heard in the opera Moses und Aron, composed between 1930 and 1932. He left Germany in 1933 and stayed briefly in Paris before emigrating to the U.S. He lived in Boston for a short time before settling in Los Angeles, where he taught at UCLA between 1936 and 1944.

Schoenberg became an American citizen in 1941. He continued to compose until the end of his life, sometimes using 12-tone or serial methods, sometimes returning to more conventional styles. Among his works from this period are the Violin Concerto (1936), the Piano Concerto (1942), and the String Trio (1946). At his death, he was still working on the last part of his Opus 50, consisting of three religious choruses which explore the relationship between man and God. These pieces are the culmination of a strain in his music that began with the unfinished oratorio Die Jakobsleiter (begun in 1917) and found its most intense expression in Moses und Aron. Schoenberg died at his Los Angeles home on July 13, 1951.

Schoenberg was the most conspicuously revolutionary figure in 20th-century music. Many of his compositions sound perplexingly difficult, even 60 or 70 years later. Some critics have argued that his system, while revolutionary in principle, simply replaced one set of rules with another even more rigid and complicated one. But his musical influence has been enormous. Many other major 20th-century composers, from Webern and Berg to Igor STRAVINSKY, Aaron COPLAND, Karlheinz STOCKHAUSEN, and Pierre BOULEZ, have used or developed his ideas.

For all the emphasis on theory in Schoenberg’s music, it is far from sterile. Schoenberg was deeply affected by the turbulent and terrible events of his age, as is heard in works such as his opera Moses und Aron (1932), and his cantata A Survivor from Warsaw (1947), which deals with the grim subject of Nazi persecution and war crimes. He also made several arrangements of other composers’ music, including an enchanting one of Johann Strauss II’s “Emperor Waltz,” recalling his own childhood in Vienna.

Richard Trombley

SEE ALSO:

CHAMBER MUSIC; ORCHESTRAL MUSIC; SERIALISM; VOCAL AND CHORAL MUSIC.

Bailey, Walter B., ed. The Arnold Schoenberg Companion (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1998);

Rosen, Charles. Arnold Schoenberg (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

Das Buch der hängenden Gärten; Erwartung; Five Pieces for Orchestra; Five Piano Pieces; Gurrelieder; Moses und Aron; Ode to Napoleon Bonaparte; Pelleas und Melisande; Piano Concerto; Pierrot lunaire, Serenades; A Survivor from Warsaw; Verklärte Nacht; Violin Concerto.