YOU ARE WHAT YOU WEAR

YOU ARE WHAT YOU WEAR

BY RANDALL LANE

This feature appeared in the 1996 Forbes 400 edition.

JOHN GRESS/AP

IT’S EARLY IN THE SUMMER OLYMPICS in Atlanta, and Nike, Inc.’s founder, Philip Hampson Knight, is exactly where he wants to be: about ten rows off the court, watching the U.S. basketball Dream Team pound its Lithuanian opponents. Knight has a vested interest in the game—eight of the 12 American players are Nike endorsers. But at any given sports event in the world, it’s tough for Phil Knight to root too avidly: Lithuania’s top player, Arvydas Sabonis, is a Nike endorser, too; like the Americans, his sneakers bear the company’s omnipresent “swoosh” logo.

Knight has built a big company and a giant fortune on what a decade or so ago would have seemed an unlikely product: athletic shoes. In less than a decade this also-ran sneaker company has emerged as one of the world’s great brand names. Among the 1,200 U.S. brands tracked by Young & Rubicam, Nike ranks among the top 10, alongside Coke, Disney and Hallmark. The power of the Nike label translates into impressive figures. In fiscal 1996, ended May 31, Nike sold $6.5 billion worth of sneakers, apparel and sports equipment, with net profits topping $550 million. Stop and ponder that: a net profit margin of 8.5% on what would seem to be a commodity product. Nike’s sales and profits have grown 71% and 80%, respectively, since fiscal 1994. Meanwhile, its closest rival, Reebok, has grown just 9%, to $3.6 billion, with profits sliding 43%, to $145 million.

This has resulted in huge profits on Wall Street. Nike shares have quintupled since the beginning of 1994, while Reebok trades at the same price it did five years ago. Whereas Nike and Reebok have historically been valued at 10 or 12 times earnings, Nike’s P/E is now a Disney-like 30. Another telling sign: Phil Knight’s 35% stake in Nike makes him the sixth-richest person in America, with a recent net worth of $5.3 billion. Only Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, Paul Allen, John Kluge and Larry Ellison stand above him on The Forbes 400.

It’s tempting to say this kind of profitability can’t last in such an easy-to-copy product. Warren Buffett would not agree. His Geico Corp. dumped its 3.5-million-share stake in Reebok last year, but as of its most recent filing still holds its 2 million shares of Nike. Buffett sees that Nike isn’t about shoes. It’s about entertainment, fashion—an image much admired by impressionable young consumers.

Knight’s success has been based on the realization that shoes long ago ceased being a luxury and are on their way to becoming a disposable consumer good. Since quality scarcely varies from shoemaker to shoemaker, Knight has taken the sneaker and transformed it into a status symbol. Image is all, or nearly all, and as with savvy fashion sellers, there is a new model for every season. There are new baseball shoes in the spring, new tennis shoes in the summer, hiking shoes in the fall. Year-round sellers, such as basketball and running shoes, are revamped quarterly. The top-selling Air Jordan model gets a new color scheme every three months. On average, Nike puts out more than one new shoe style every single day.

“In my era, kids grew up knowing their cars,” says Knight. “The kids nowadays grow up knowing their shoes.” Teenagers clustered at almost any Foot Locker or Sports Authority store can talk in staggering detail about the comparative benefits of, say, the 1994 and 1996 Air Jordans.

Far more than its competitors, Nike has mastered that hard-to-define concept known as “cool,” particularly among the under-30 crowd. Coke and Disney connote Americana and wholesomeness. Young & Rubicam’s research shows that Nike scores points for attitude, for irreverence. Nike spent almost $10 million during the recent Olympics airing a jarring TV ad entitled “Search and Destroy,” which paints Olympic athletes as full-fledged warriors, kicking, jumping, falling—whatever it takes for victory—all framed by a crescendo of punk rock music. The spot ends with a runner vomiting violently, and a bloody mouthpiece sailing across an image of the Nike logo. Very in-your-face.

Twentieth-Century Americans, wrote Daniel Boorstin, affiliate themselves less by their political or religious beliefs than by what they consume. Knight has made it cool to be a Nike consumer. Highly polished brogues aren’t cool-flashy, high-tech sneakers are.

So familiar has the Nike logo become to its target audience that both the sneakers and the $1.5 billion worth of non-shoe products Nike markets no longer even bother to carry the name Nike—just the Nike logo, that curvy, speedy-looking blur that has become as ubiquitous as Mickey Mouse. When some words are called for, Nike uncorks its indelible and equally ubiquitous slogan: “Just do it.”

All this savvy begs the question: How did Phil Knight, a shy 58-year-old track geek who spent the first two decades of his business career harboring a deep dislike for advertising and spin, evolve into one of the great marketers of his time? Knight responds to that with a “just do it”-inspired question of his own. “How did John Kennedy become a war hero?” he asks, before pausing. “They sank his boat.”

Knight’s boat received a powerful hit back in 1987, when Stoughton, Mass.-based Reebok came from nowhere to blow past Nike. Up until then, Nike had been the classic entrepreneurial success story.

AS A STUDENT at Stanford Business School, Knight, a former University of Oregon track star, wrote a paper on how Japanese labor could be used to create a cheaper, better running shoe. Visiting Japan, he discovered Onitsuka Tiger Co., which made its own inexpensive, high-quality running shoes. Back home, Knight teamed up with his old college track coach, William Bowerman, and in 1964 they each kicked in $500 to import Tigers, which Knight began selling from his car at high school track meets.

Worried that Tiger would find a more established distributor, Knight and Bowerman developed their own brand name, Nike, after the Greek winged goddess of victory. A local design student at Portland State got $35 to develop the logo. Then Bowerman, now 85, experienced his now-famous epiphany. “I was looking at my wife’s waffle iron, and I thought it looked like a pretty good traction device,” remembers Bowerman, who has sold most of his Nike stake to Knight over the years, but is still on Nike’s board. With the waffle-sole innovation, introduced in 1972, Nike began designing its own shoes and contracting production to Asian job shops. They were perfectly timed to cash in on America’s running boom during the 1970s. Sales were less than $3 million in 1972. By 1980, when it went public, at the equivalent of $2.75 a share on the present $124-a-share stock, Nike was selling almost $270 million worth of running, basketball and tennis shoes.

In 1983 Nike’s payroll had grown to 4,300, and by 1986 sales had hit $1 billion, but then the Reebok torpedo slammed into the hull. The torpedo came in the form of marketing.

Phil Knight’s idea of running the company was to make high-quality, low-cost shoes, get some top athletes to endorse them and let his sales force sell the product. There was an amateur’s purity to this approach. “We were the children of Holden Caulfield,” says Knight. “Nobody liked the phoniness or the hypocrisy of the establishment, including the business establishment.”

Paul Fireman had no such reservations. Reviving Reebok, an old English brand, Fireman began pitching Reebok’s leather shoes as a fashion item for the trendy aerobic-workout crowd. Reeboks became cool, while Nike retained a sort of utilitarian image. Between 1986 and 1987, Nike’s sales dropped 18%; profits sank over 40%.

Phil Knight didn’t know much about advertising. But as an old athlete himself—he once logged a 4:10 mile—Knight did understand sports, which he calls “the culture of the U.S., the language of the world.” People don’t root for a product, Knight reckoned, but for a favorite team or a courageous athlete. Nike would sell not shoes but the athletic ideals of determination, individuality, self-sacrifice and winning. Nike had always sponsored athletes. It drew the enmity of the track community as early as 1973 by paying star runner Steve Prefontaine to wear Nike shoes at a time when under-the-table handouts were the norm. Now, with his company at risk, Knight went all the way.

PREFONTAINE, WHO DIED IN A CAR CRASH in 1975, had long been the spiritual model of what people around company headquarters uniformly dub a “Nike guy”—a brilliant athlete with a competitive attitude and an iconoclastic personality. His successor was Michael Jordan, the Chicago Bulls star now recognized as the best basketball player in history. Calling in an unknown but innovative Portland, Ore.-based ad agency, Wieden & Kennedy, Knight used Jordan to give Nike a makeover. Spike Lee, a young movie director with attitude, filmed spots that lionized Jordan as the man whose hard work (and fancy shoes) enables him to fly. Roughly 35 Nike ads later, Jordan is the most popular athlete in the country, according to New York-based Marketing Evaluations.

Nike headquarters in Beaverton, Ore. is today a shrine to athletics, with hundreds of bronze plaques and giant banners of Nike-backed athletes; the complex is surrounded by miles of running trails and a giant lake.

Today Nike probably pays out $100 million a year to get athletes to use and pitch Nike products. As Nike regained its momentum, Knight recruited a whole team of athletes: John McEnroe, then Andre Agassi in tennis; Nolan Ryan in baseball; Deion Sanders in football; Carl Lewis and Alberto Salazar in track; football/baseball star Bo Jackson for multisport shoes. And a bunch of basketball players, including Charles Barkley and Scottie Pippen.

This stable of athletes from different sports enables Knight to segment the market but at the same time build a single brand. By defining each sport as a separate category rather than just lumping athletic shoes together, Knight also broadens his base. And by focusing its sponsorships on individual athletes over events or leagues, Nike, despite its size, maintains its cool, outsider image.

Here’s how well this strategy has worked: The average American teenager now buys 10 pairs of athletic shoes a year, six for specific sports, four for fashion. For Nike, that translates into 6 million teenagers buying over $1 billion worth of Nike shoes.

KNIGHT’S MARKETING MACHINE was in classic form at the Olympics this summer. Nike wasn’t a sponsor. Knight let companies like Coke, Sara Lee and Anheuser-Busch fork over up to $40 million each for the privilege of putting Olympics rings on their products. Nike permeated the event by sponsoring hundreds of individual athletes and teams, who repaid by sporting the swoosh on their uniforms and shoes. Just outside Centennial Olympic Park, where most of the official sponsors were shoehorned in booths, Knight turned a four-story parking garage into Nike Park, with basketball shooting contests, sneaker models, a Nike store and odes to Nike athletes. All this plus $30 million for advertising, including the violent “Search and Destroy” TV spot, and billboards throughout Atlanta that flipped the touchy-feely Olympic ideal on its head, proclaiming: “You don’t win silver, you lose gold.” A stranger wandering onto the scene might have concluded that the Games were a promotion for Nike. In a way, they were.

Aware that business people, like athletes, need a challenge, Phil Knight has challenged his 15,500 employees to make Nike a $12 billion company by the end of the decade. To achieve this 13%-a-year growth target, Knight is branching into women’s sports, signing up dozens of top women athletes and backing them up with heavy spending. Here, too, Knight is as contemporary as you can get. In ads now airing, little girls implore their parents to give them a ball instead of a doll.

Coca-Cola has conquered the world. Why not Nike? Knight’s statistic of the moment: While the average American spends $12 a year on Nike products, the average German spends just $2. Knight’s agents are at work to close the spending gap, signing up the best athletes in each country to push Nike products locally—baseball player Hideo Nomo in Japan, the Boca Juniors soccer team in Argentina, Germany’s Formula 1 racecar champion Michael Schumacher. All “Nike guys” who’ll thumb their noses at social conventions while succeeding brilliantly on the playing field. What the world’s yuppies would like to do, but can’t. Just as ordinary folks once went to the movies to experience life as lived by glamorous, beautiful people, they now dress in symbols associated with what they would like to be—but aren’t.

Shoes? Or show biz? A mixture, of course. Nike Town stores feature commercials blaring on multiscreen televisions. Basketball courts allow customers to try out shoes. Gear autographed by Nike athletes abounds. Each sport has its own room in the store; it is not unusual for customers to buy three or four pairs of shoes in a single visit.

Opened three years ago, the Chicago Nike Town now ranks with the Navy Pier and the Lincoln Park Zoo as one of the city’s top tourist attractions. There are now six Nike Towns, with a brand-new 90,000-square-foot model debuting on New York’s 57th Street in November—Nike Town’s New York rent, says landlord Donald Trump, is about $10 million a year. Three more Nike Towns are scheduled to open next year. The stores move merchandise, of course. More than that, they enhance the all-important image.

Extending the brand over a broader array of products, Nike has expanded into in-line skates, swimwear, hockey equipment, even sports sunglasses. Knight feels he can leverage the Nike image almost without limit, as long as Nike stays within sports.

Reminded that lots of older people find Nike ads revolting, Knight just shrugs. “It doesn’t matter how many people you offend,” he says, “as long as you’re getting your message to your consumers. I say to those people who do not want to offend anybody: You are going to have a very, very difficult time having meaningful advertising.” F

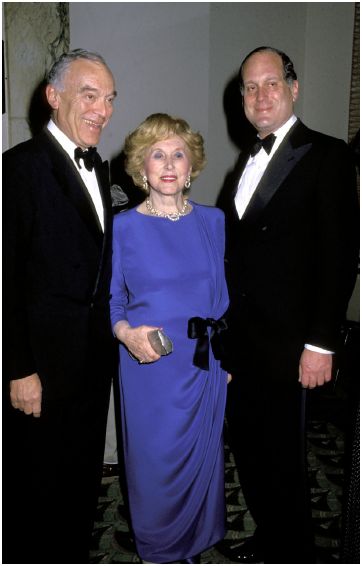

RON GALELLA/GETTY IMAGES

Estee Lauder

Leonard Alan Lauder

Ronald Steven Lauder

Mother, 2 sons. Cosmetics. NYC and the Hamptons. Estee: ageless “Blue Lady” (her color). Widowed: “I never thought I’d make it big. If I felt I had made it, I would be somewhere nice, like St. Moritz, skiing.” Josephine Esther Mentzer born to Czech-Hungarian immigrants in Queens. Peddled skin creams for Viennese uncle, attached her name to several brands. Started company with 4 products 1946; pestered department store buyers until she landed orders. Married Joseph Lauder after summer resort romance. He: administrator, escort. She: social butterfly, product developer, promoter. Claims to “see” fragrances, consumer trends. Built one of the world’s largest cosmetic companies: Estee, Clinique, Aramis, Prescriptives, now Origins (natural products, recyclable containers for younger, sincere crowd). Self-help booths at department stores popular. Expanding internationally: Russia, Eastern Europe, India, China. Overall sales up modestly. Estee no longer in day-to-day operations. Rumors of merger with Procter & Gamble petering out. Leonard: 61. Married, 2 sons. Current CEO, outspent rivals on R&D, now credited with much of company’s growth. Wife Evelyn a senior executive; spearheading company effort to raise money for breast cancer research. Son William running Origins, waiting in wings. Ronald: 50. Married, 2 daughters. Left company 1983 to become deputy assistant defense secretary (NATO), ambassador to Austria. Ran for mayor of New York City 1989, badly beaten in primary: spent estimated $350 per vote. Went back to Estee. Sponsored term limit referendum for NYC officials 1993; won big. Briefly considered 1994 New York GOP gubernatorial bid. He, mother, brother share over $3 billion.

From the Forbes 400 1994 Issue

William Jaird Levitt

Home builder, Millneck, N.Y. 75. Twice divorced, remarried; 2 sons, 3 adopted stepdaughters by third marriage. Before WWII, small home builder Long Island. During war, developed mass production building technique on barracks. Applied to homes 1946: built 3 Levittowns, invented tract development concept. Sold Levitt & Sons 1968 for $90 million; sailed off, chairman of the board, in custom-built yacht with French wife, art collection. Bored; began with new company 1978; now building retirement Williamsburg communities, Orlando and Tampa Bay, Fla. Estimated net worth: over $100 million.

From the Forbes 400 1982 Issue

Pamela M. Lopker

$425 million. Software. Carpinteria, Calif. 42. Married, 2 children. Richest self-made woman on The Forbes 400. Graduated U.C. Santa Barbara, 1977. Started QAD in 1979, wrote program that kept track of shoemaker’s sales orders; later expanded program to take care of accounting and inventory. Moved from cobblers into factories, upgraded software to handle materials planning, forecasting, cash management for Philips Electronics, Unilever, Ford. Bought partners out 1981. Private QAD now replacing old-fashioned, monolithic applications with “object-oriented programming”—independent, interchangeable modules of programming that can be assembled to create complex, flexible programs. Gearing up to be compatible with Microsoft’s NT 4.0 operating system. QAD known for nontechie approach: learn customer’s industry inside and out, so “we look like we come from that industry.”

From the Forbes 400 1996 Issue