In October 1908, the Hungarian-born society portraitist Philip de László told the sixteen-year-old Vita of his desire to paint her ‘in a Velázquez style’. Two years later he did so. His image of extravagant languorousness initially delighted Vita. Later she dismissed it as ‘too smart’ and refused to hang it.

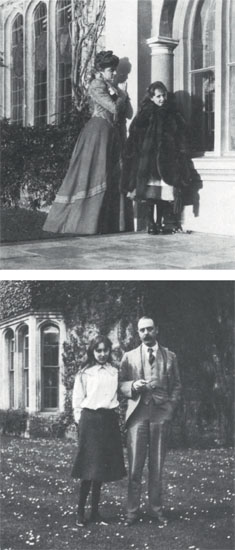

Vita with her parents as a child at Knole. She wrote that what her difficult mother Victoria (above) meant to her was ‘a mixture of tragedy and – no, not comedy, but sheer fun’. Her bond with her father Lionel (below) was largely unspoken.

Knole, the love of Vita’s life. She claimed it possessed ‘all the quality of peace and permanence; of mellow age; of stateliness and tradition. It is gentle and venerable.’ It was also imbued with intense romance for Vita, who was a lonely and imaginative child.

In a hidden drawer in an ebony cabinet in the King’s Room, six-year-old Vita left a note: ‘Dada, Mama and Vita looked at this secret drawer on 29th April 1898.’

In 1913, Lionel and Vita were accompanied to court during the Scott case by Harold Nicolson and Rosamund Grosvenor. Both were in love with Vita.

‘Never before or since, have I felt so much like royalty,’ wrote Vita following Lionel and Victoria’s success in the Sackville succession case of February 1910.

For a fundraising Shakespearean masque in the summer of 1910, Vita, as Portia, borrowed the velvet robes worn by Ellen Terry in a production of The Merchant of Venice in 1875. Clare Atwood’s portrait depicts her as a romantic Italian youth.

Vita and her father’s mistress Olive Rubens in one of the Omar Khayyam tableaux staged by Viscountess Massereene in aid of war charities in June 1916.

‘When you see a person, a body, marvellous casket and mask of secrets, what do you think?’ Vita asked in her first novel, Heritage.

A young Harold Nicolson – in his own words ‘supremely ineligible’, in Vita’s not ‘the lover-type of man’, ‘a playmate, clever and gay’.

Among Harold’s contenders for Vita’s hand was Henry Lascelles (centre), heir to the Earl of Harewood and an income of ‘£31,000 a year from his land alone, plus plenty of cash’.

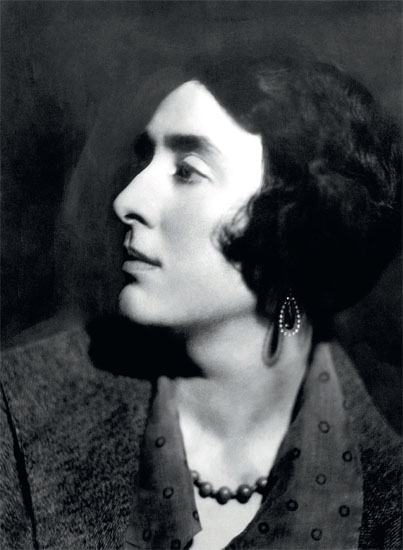

Violet Keppel in 1919, in a portrait by John Lavery. Vita described her as ‘this brilliant, this extraordinary, this almost unearthly creature’. Their affair changed the course of Vita’s life.

Vita as mother – with Ben (left) and Nigel (right) in 1924.

Vita’s lover Mary Campbell painted this view of Long Barn in the winter of 1927. Vita had bought the part-medieval, extended cottage for £3,000 in 1915.

Vita broadcast for the BBC for the first time on 18 April 1928. After embarking on an affair with Director of Talks Hilda Matheson, she became a regular and highly regarded broadcaster for the Corporation.

Nigel, Vita and Ben at Long Barn. Vita’s decorating included distinctive features of the rooms of her childhood: tapestries, seventeenth-century looking glasses and Jacobean oak furniture.

Vita ‘in the prime of life, an animal at the height of its powers, a beautiful flower in full bloom. She was very handsome, dashing, aristocratic, lordly …’

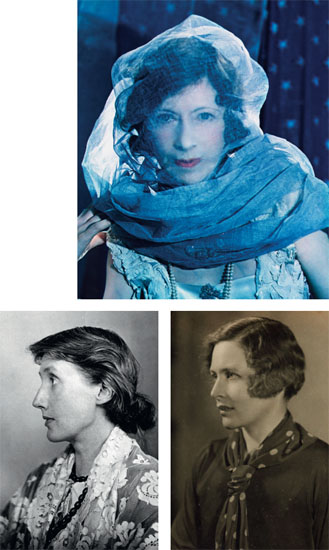

‘You do like to have your cake and eat it, – and so many cakes, so many, a surfeit of sweet things’, one lover teased Vita in 1932 of her habit of juggling multiple lovers. Among Vita’s lovers were (clockwise from top): Dorothy Wellesley, Hilda Matheson and Virginia Woolf.

At Sissinghurst, Vita realised her long-held fantasy of retreating into a tower with her books. Her writing room was on the first floor of the tower, with a small library in the adjoining octagonal tower.

Vita conceived the idea that would become the White Garden, beside the Priest’s House, in December 1939. It has since become one of the most famous planting schemes in the world.

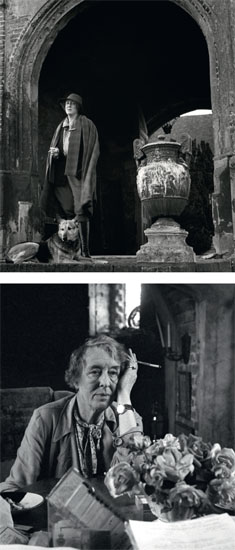

In a photograph taken in 1948 by John Gay (above), Vita, on the steps of the tower at Sissinghurst, wears the uniform of breeches and gaiters she had first adopted thirty years earlier. The cigarette, in its holder, is also a feature of an equally theatrical image taken by John Hedgecoe four years before Vita’s death (below).

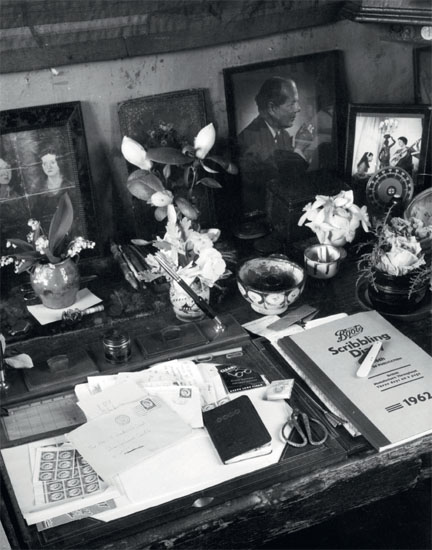

Vita’s desk on the day she died, 2 June 1962, with her preferred collection of small-scale flower arrangements, a photograph of Harold and sheets of stamps.