CHAPTER 5

Going for Broke in Texas

“We want Ann!” came a chant from the crowd in Atlanta, followed by raucous applause. I looked out from the gigantic, ocean-liner-size stage where I sat alongside my brothers, Clark and Dan, and my sister, Ellen, taking in the scene. It was classic convention-style pandemonium: folks were throwing beach balls, wearing crazy hats, and blowing horns. In a few days Michael Dukakis would accept the 1988 Democratic nomination for president from this very stage. But right now the entire convention was focused on the woman of the hour, my mom.

True to form, from the moment she had gotten the call inviting her to deliver the keynote speech at the Democratic National Convention, Mom had approached the task with military precision, right down to the eye-catching blue dress she knew would look just right on television. We had spent the days before holed up in her hotel room, as she worked on her speech. It was both thrilling and nerve-racking. Everyone on her team was suggesting lines, making edits, crossing things out, and making notes in the margins. Suzanne Coleman, who had written for Mom since she first got into politics, was the primary writer. Suzanne had the driest wit imaginable, knew Mom’s voice, and could tell a story and think up a great line better than anyone. Jane Hickie was with us, along with Mary Beth Rogers, Mom’s political guru. Kirk and I were offering suggestions and advice, and Lily Tomlin and Jane Wagner were faxing in lines from Los Angeles. We went through draft after draft and, as always, finished at the last possible second.

Finally the moment had arrived, and I found myself onstage at the Omni Coliseum, sitting on the edge of my seat and waiting for Mom to appear. I looked to my left and caught sight of Kirk and Lily in the audience. Lily was sitting on Kirk’s lap, and I thought how wonderful it was that Mom’s granddaughter was getting to see this in person.

This was not Mom’s first time on the national stage, but it was the most significant. Four years earlier, at the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco, she had given a speech seconding Walter Mondale’s nomination for president. But her speech was totally unremarkable and landed like a lead balloon. Sitting through that first convention speech, she and I learned two important lessons: first, no one in the convention hall pays attention to what’s happening onstage in the midst of all the chaos and noise in the audience; second, you can’t hope to speak to the conventioneers—your audience is the millions of people watching back home.

As a result Mom had just one request of the convention organizers in Atlanta: to bring the house lights down for her speech. The organizers were worried that the networks would balk at this, but Mom prevailed. Sure enough, when the lights dimmed, a hush fell over the crowd. People settled in to listen, just like she knew they would.

I heard Mom coming before I saw her. She entered to the song “Deep in the Heart of Texas.” The second she came around the corner, thousands of conventioneers stood and cheered, holding signs reading “Democrats  Ann Richards.” Kirk had his buddies in the labor movement print them and pass them out—it was such a boost. And then, of course, she gave the speech of a lifetime. “Twelve years ago, Barbara Jordan, another Texas woman, made the keynote address to this convention, and two women in about 160 years is about par for the course,” she began. “But if you give us a chance, we can perform. After all, Ginger Rogers did everything that Fred Astaire did. She just did it backwards and in high heels!”

Ann Richards.” Kirk had his buddies in the labor movement print them and pass them out—it was such a boost. And then, of course, she gave the speech of a lifetime. “Twelve years ago, Barbara Jordan, another Texas woman, made the keynote address to this convention, and two women in about 160 years is about par for the course,” she began. “But if you give us a chance, we can perform. After all, Ginger Rogers did everything that Fred Astaire did. She just did it backwards and in high heels!”

This is nothing like San Francisco, I thought, and I knew that my brothers and sister were thinking the same thing. The speech was perfect, better than anyone could have hoped. Mom was landing every line with the audience, and they were captivated. Her speeches were always better in person than on paper, and this was no exception. She brought the house down when she talked about George H. W. Bush, who, after two terms as Ronald Reagan’s vice president, was now the Republican candidate for president. “And for eight straight years George Bush hasn’t displayed the slightest interest in anything we care about. And now that he’s after a job that he can’t get appointed to, he’s like Columbus discovering America—he’s found child care, he’s found education. . . . Poor George, he can’t help it—he was born with a silver foot in his mouth.” The crowd roared.

We were all beaming with pride by the time Mom got to the closing section. Turning sentimental, she said, “I’m a grandmother now. And I have one nearly perfect granddaughter named Lily. And when I hold that grandbaby, I feel the continuity of life that unites us, that binds generation to generation, that ties us with each other. . . . And as I look at Lily, I know that it is within families that we learn both the need to respect individual human dignity and to work together for our common good. Within our families, within our nation, it is the same.” I looked out into the audience again. Kirk, who has never been a crier, had tears in his eyes. He was bouncing Lily up and down, knowing she was too young to understand why her grandmother was up on the stage in the first place.

Someone had brought Mom’s parents to their local TV station in Waco, and they streamed in live to talk with Mom after the speech. The news announcer turned to Poppy, my grandfather, and said, “Well, Mr. Willis, when you told your daughter that she could do anything she wanted to do if she just worked hard enough, did you ever dream that she would be doing something like this?” Poppy laughed and said, “Why, hell, I didn’t even know there was a this!”

Dukakis went on to a crushing defeat, but the speech made Mom a household name. (I still run into students who study it in communications class. In fact when Lily was in college, her political science class watched it to analyze public speaking, and she had to fess up that Ann Richards was her grandmother.) Candidates asked her to help them with their campaigns. Women everywhere wrote letters, asking her to run for governor of Texas, or better yet, president of the United States. Her whole world was opening up, and nothing would ever be the same.

• • •

The ’80s had brought enormous changes for Mom, and the most life-changing of these was that she had gotten sober. Drinking had been such a big part of my parents’ social scene that I didn’t think much of it until I was in high school. I would learn only later that when I was quite young, Mom had asked her doctor if she might have a drinking problem.

“I don’t think so, Ann. Why? How much do you drink?” he asked.

“Well, I usually have two or three martinis before dinner.”

“Oh, that’s nothing to worry about,” he reassured her. “I drink that much myself!”

I was home from college one Christmas when a friend brought her a present. As soon as Mom unwrapped it, she burst into tears. It was a light sculpture by a local artist, and it flashed in pink and white, “I’m okay, you’re okay.” She was definitely not okay. It was hard to see Mom so sad, and have no idea how to fix it.

In those days there was no easy way to publicly declare your addiction and go for treatment. It wasn’t something people talked about, let alone did. I’m not sure who finally decided to break that unspoken code, but some of her friends consulted with a couple who specialized in interventions—a miserable process where loved ones confront the addict at a group meeting to persuade him or her to get help.

As with so many unpleasant things in life, the details of that day are hazy, except for this: it was horrible. I have never been good at keeping secrets, and it felt awful to plot this whole event behind Mom’s back. As the oldest child, then in my early twenties, I was in on it, along with Dad and many of Mom’s good friends. We gathered in someone’s living room, though I cannot remember whose, and she arrived under some other pretense. We sat down in a circle of chairs, and Mom had to sit and listen to each of us tell how her drinking had affected us. “I was scared to get into the car with you when you were drinking,” I told her, “and scared for the other kids too.” That was all I could get out, but it was enough.

She heard so many hard and heartbreaking statements that day that she left for treatment in Minneapolis—she called it “drunk school”—the same afternoon. Later we spent a week with her to do family therapy. It was a sad time for everyone, especially Mom. I know how terrible it must have been and how ashamed she felt. But she took on therapy like everything else she’d ever done, full-on, and she never had another drink in her life. She later said that getting sober saved her life, but I don’t think she ever forgave any of us for the way we went about it.

When Mom went away for treatment, she predicted that it would be the end of her marriage. She was right: she was sober for less than six months when Dad moved out, and though she saw it coming, she was crushed.

At the time, I was working in Texas at my first union organizing job. Mom wanted companionship more than anything else as she was beginning the slow adjustment to living on her own for the first time, so we decided I’d move in with her. Who would have thought we’d be making dinner and watching bad TV together at that point in our lives? It was an awkward transfer of roles: she was staying at home in the evenings, and I was going out with friends, after making sure she had dinner and was going to be okay for the night.

It was a temporary arrangement, and I was anxious to get on with my life. As for Mom, she eventually got used to living alone. More than that, she came to love her newfound independence. She dated Bud Shrake, the Texas sportswriter and author, for many years, but she never wanted to live with a man again. That way, she explained, they could go out and have a good time, but she didn’t have to take care of anybody. Most men her age wanted someone to be their cook, nursemaid, and support system—and once Mom came into her own, she wasn’t about to go back. She felt free.

When she ran for state treasurer in 1982—her first state office—Mom made a decision that while she would talk about recovery, she was not going to answer the onslaught of questions she knew were coming: Who did you drink with? Were you ever drunk in public? Did you endanger your kids? Because she refused to open that can of worms, her opponents used every opportunity to speculate about the extent of her addiction and what other substances she might have used along the way.

Despite the personal attacks, she was elected treasurer, becoming the first woman to hold statewide office in Texas in more than fifty years. During her two terms, she brought the job into the twenty-first century. When she started, there were drawers full of checks that hadn’t been cashed. She computerized the agency, cashed the checks, and, lo and behold, actually made money for the state. To most of the men who made up the Democratic Party establishment, the job seemed like appropriate women’s work: nonthreatening, out of sight, kind of like keeping track of the family budget.

In Texas, being too big for your britches is just about the worst thing you can be, and that goes double if you’re a woman. There was a long list of Democratic men who had been angling for the governor’s job for a while, and they would have been happy for Mom to stay where she was. Her male counterparts in the Texas Democratic Party saw her as a colorful addition to the statewide team, but they didn’t think of her as their competition, and certainly not as their leader. But after her star turn at the Democratic National Convention, and eight years sober, she was starting to think seriously about taking on what was certain to be an even more grueling campaign for governor. She gave us fair warning that if she decided to run, she’d need our help.

When my phone rang a few months after the convention, I was at home in California, working, raising a toddler, and about as far removed from Texas politics as you can get. I wasn’t ready for what she was about to ask.

“Cecile, I’m gonna do it,” she said, cutting right to the chase.

I took a deep breath.

“The women are on fire,” she continued. “But I’m going to have a tough Democratic primary. Really tough. They are going to say I’m a drug addict and hassle me about being divorced. But if I don’t do it, I will always wonder, What if? I just can’t live with that.”

As independent as Mom was, she had the same human frailties that we all do. After my parents’ marriage unraveled, Mom had come to lean on her kids for her emotional support. My mother was a very complicated person, and although she was enormously competent and driven, she was also unsure of herself. She was always struggling to overcome the insecurities of her upbringing, trying to prove she was just as smart as the other kids. On top of that, she was trying to succeed in a political environment that was inherently hostile to women.

For her to be as fearless and unflappable as she was in public, she needed a private place to retreat—somewhere she could be honest and open about her anxieties and fears—and that was with her family.

Now she was counting on us to be there for her during what promised to be her most daunting challenge yet, both in the Democratic primary and in the general election. Leave it to Kirk to put everything in perspective. “If your mom needs us, we have to go back home,” he said. I loved him for that.

It was never a question of if we would go, but the decision came with regrets. Kirk and I both felt loyalty toward our teams and worried we were letting them down. At the same time, as I packed to move to Texas, I thought about how improbable and extraordinary this was—that someone who had spent so much of her life as a housewife and had only recently gotten into politics not only wanted to be governor but actually thought she could win.

Of course, it was not lost on me that men take these chances all the time. They say, “I work for an advertising firm and have never been in public office, but I’m going to run for Congress.” Women, on the other hand, say, “I was thinking about applying for that job, but I haven’t finished my PhD yet.” Even my daughter Lily, when she was steadily working her way up the career ladder, doing grunt work on campaign after campaign, couldn’t believe that her male classmates were already planning to run for office or applying to jobs they clearly weren’t prepared for. It breaks my heart that young women who should have all the confidence in the world still hold themselves back.

My mother decided she wasn’t going to wait until she had the perfect résumé, and she certainly wasn’t going to wait until she was guaranteed success. Every political race she’d gotten into, it was because she knew that she was qualified and could do a better job than the incumbent, even if she was the only one who thought so.

• • •

Mom’s campaigns always brought together family and friends in a way that resembled a Judy Garland–Mickey Rooney “Let’s put on a show” performance, and the governor’s race was no exception. So for Kirk, Lily, and me, our family life became consumed by the campaign.

Practically overnight, campaign headquarters became our home away from home. It was a dump, but it reminded Kirk and me of the places where we had worked before, the makeshift union halls and organizing offices. We started there first thing every morning and didn’t leave until late at night. We never even unpacked all of our boxes at the house we rented in Texas, and we never set foot in the backyard.

Lily was two and a half. Our routine was to drop her off at day care the moment it opened and pick her up a minute before it closed (on a good day). Afterward we’d bring her back to the office for pizza while we spent the evening making phone calls to potential volunteers and county coordinators. These may not have been ideal circumstances for other young families, but we were in our element. It was the ultimate organizing challenge; we knew the only way we could win the election was to build a grassroots operation in every part of the state. Texas has 254 counties, and our first priority was finding a coordinator for each of them, a herculean task.

Mom was an upstart candidate, and the people who ran her campaign were a combination of family and friends, plus women and political types who were intrigued by the idea of her running. We didn’t have the establishment kingmakers, but we had a lot of talent. Mom’s longtime support system, including Mary Beth Rogers and Jane Hickie, were on board, along with Suzanne Coleman, who was writing speeches as fast as she could. Jack Martin was a trusted adviser throughout, and slowly but surely we built a statewide team. Her best friend, Virginia Whitten, organized meals that volunteers would leave for Mom in her fridge every week. Kirk was the de facto field director, overseeing the volunteers and staff responsible for running the campaign at the local level and getting voters to the polls on Election Day. And my brother Dan was Mom’s traveling aide and “purse carrier,” as she called him, though in reality he was so much more.

Lily and I became stand-ins for Mom, along with my sister. Geographically Texas is bigger than France. Campaigning in a state that size is overwhelming, even for someone as relentless as Ann Richards. Mom took to heart the words of the legendary speaker of the US House of Representatives Sam Rayburn: If they can’t meet the candidate, they want to meet the candidate’s family. The Richards clan was out in force.

The Ann Richards campaign for governor, featuring Lily, who traveled nearly as many miles as the candidate.

Our car was like a mobile campaign unit, jammed with stickers and yard signs. On many days, early in the morning, I’d throw Lily, still in her pajamas, in the backseat and we’d hit the road, stopping to change at the local Dairy Queen. Food on the road was in short supply. Out of necessity I learned the location of every Whataburger across Texas, where I could get a fish sandwich and even top it with jalapeños—that was a good day! The definition of dressing up was stopping at the local 7-Eleven to buy a new pair of panty hose in “suntan” on the way to a speech.

Because Kirk and I had lived in Tyler, I knew East Texas like the back of my hand. I drove to every county fair and barbecue. Every town I went to, I hit the local café or the courthouse to shake hands. Did you know there is an annual tamale toss in Del Rio? Oh, there is.

There was no crowd too small to hand out “Ann Richards for Governor” cards. A lot of people had voted for Mom for treasurer, but they didn’t know much about her. Our goal was to defang this wild idea of electing a progressive woman and to let them know that Mom was just like them. It was exciting; retail politics was as good as it got. Getting to do the color commentary for the Jasper High School baseball game on local radio—what could beat that?

Best of all were the women I met along the way. You better believe the Cass County Democratic Women in Atlanta, Texas, had been waiting for a chance like this all their lives. Women had been behind the scenes, running Democratic campaigns across the state, for as long as anyone could remember—making the calls, dividing up the block-walk lists, organizing the fundraisers and chili suppers. Now they were doing it all for a woman, and that was a great big deal. Everywhere I went, women my mother’s age and often with her hairdo would grab me by the arm, their eyes shining, and say, “I never thought I’d see the day!” Mom said that being a woman running for governor was like being a three-headed dog at the carnival: she was a novelty, so we got a crowd pretty much wherever we went.

The worst part of campaigning was dealing with the negative press, the rumors and personal attacks on Mom. When the news started off with “Today Ann Richards was accused of . . .” I’d turn off the TV. My job was to be the most enthusiastic warrior I could be, and that often required fielding questions from reporters that were based on half-truths and rumors. I’ve found that you have to decide what it is that makes you a good organizer, and what saps your strength and energy. For me, television news has always been the latter.

It’s easy to get caught up in the press and assume everyone else is as well, but I discovered that in most towns, people were busy just living their lives. In those places we could make a big impact just by meeting people and listening to their concerns. There’s no better way to refute false attacks than to have a conversation with people and tell them what you know to be the truth.

Not everyone was a fan—witness the homecoming parade at Baylor University in Waco, Mom’s alma mater. My brother Dan had decked out his ’57 Ford pickup with bunting on the sides and hay bales in the back. We climbed up into the truck. Lily sat on the hay, the center of it all, dressed in a darling red, white, and blue dress, and threw candy to the paradegoers. She had become a bit of a campaign mascot—whether she was riding on a float for a Cinco de Mayo parade in Laredo or handing out Ann Richards campaign materials at the annual Luling Watermelon Thump. She had learned early on to look someone in the eye and shake their hand, and people were charmed by her. But even Lily’s winning personality wasn’t always enough. We got a few scowls in the homecoming procession—it was conservative territory, after all, so we weren’t expecting a welcoming committee. But it was too much when an older gentleman, dressed in a checkered shirt and jeans, stepped up and shot the finger at my toddler. Welcome to hard-knuckle politics, I thought.

The primary was our first big test. Mom’s Democratic opponents were former governor Mark White and Attorney General Jim Mattox. Mattox had taken on every corporate special interest while in Congress and campaigned for his current role in a retired Hostess Twinkie bread truck with “The People’s Lawyer” painted on the sides. He was the one to beat. He was constantly planting bogus stories in the media and would do anything for attention. I’d been to more than one wedding reception where he was standing in the receiving line right after the bride and groom. At one point he issued a press statement saying he had a poll that showed him in the lead, which he wasn’t. The press called, asking us for a comment. Our press secretary, Monte Williams, faxed them back an article from the National Enquirer attesting that 62 percent of Americans believed Elvis was still alive.

The one key for any Democrat in the primary was getting the labor endorsement, because it guaranteed money, workers, and a statewide campaign organization. Mattox had been labor’s go-to guy, and everyone thought he had the endorsement in the bag. But we had one card to play, and that was Mom’s support from the public employees union. AFSCME leaders like Dee Simpson bucked the rest of organized labor; their union was made up primarily of women and people of color, and they were up for the fight.

The state labor convention was make-or-break time. Kirk and I went into high gear, with one goal: block Mattox from getting the endorsement. This is where our past experience running dozens of union elections helped: we knew how to count votes. We walked the convention floor along with a Texas state representative, Lena Guerrero, and an underground network of women labor leaders and, with their help, managed to keep labor from endorsing any candidate. The papers covered it as a huge win for us and a serious blow for Mattox.

Besides labor, there was one other group that swooped in to help us. The legendary Ellen Malcolm had recently started a national organization, based out of Washington, called EMILY’s List, which stood for Early Money Is Like Yeast (it makes the dough rise). They knew full well that this would be an uphill race, but they sensed Mom’s potential early on. Without them, I’m not sure we would have made it through the primary. They called on women around the country to contribute to Mom’s campaign, and women did. They were the financial lifeblood of the early days of the campaign, and thank goodness.

Texas has an outsize law-and-order kind of culture, and this campaign was no exception. Mattox’s slogan was “Texas Tough!” Both of Mom’s opponents had been attorneys general, and the primary campaign became a classic pissing match over which one had been more successful at executing inmates on the state’s robust death row. Both men actually ran competing ads that showed face after face of men they had executed, each one trying to outdo the other. The campaigns were so over-the-top that Saturday Night Live ran an unforgettable parody featuring a Texas gubernatorial candidate sitting on a pile of coffins. The obvious implication of the original ads, and an undercurrent running through the entire campaign, was that a woman wasn’t tough enough to keep Texas safe.

Everything is considered fair game in politics—even if it isn’t true. Mom’s very public recovery from alcoholism opened the door for her opponents to accuse her of being an addict who couldn’t be trusted to hold office. The fact that she was unmarried allowed for all kinds of public speculation about her sex life. As Mom would say, “They said I couldn’t get a man, couldn’t keep a man, or didn’t go with men.”

The attacks were hard on everyone, but they especially stung my sister and me. I hadn’t realized how fiercely protective I was of Mom until I saw her attacked on television night after night. Whether or not I intended to, I fell into the role of her biggest defender. At times I pulled myself out of a campaign meeting, saying I’d rather be on the road at some county fair instead of in a back room making cutthroat decisions about how to respond to the latest ad against her. I was just too close to the situation.

Fortunately Kirk was more cool-headed, as was my brother Dan, who traveled with Mom on the campaign trail. Dan and Mom had always been particularly close. If I was the insufferable first child, always striving to be perfect, Dan was the easygoing, fun-loving second kid who brought joy to everyone, and to Mom in particular. He has always been a car nut, and growing up there was always a car in some state of disrepair on our front lawn. One sat for so long that Mom strung Christmas lights over it for the holiday to make her point. They both laughed over that.

Mom could be acerbic with staff, and no one took more of the heat than Dan. On those long, tough days, he had to absorb all of her fear and frustration. He was so loyal, and I was always impressed by the way he seemed to take it in stride. It wasn’t until recently that he confessed he had once been pushed almost to his breaking point. It had been another exhausting day on the road, with event after event. They were sharing a hotel room in Houston—there was never enough money for everyone to have their own room—and she lit into him about something or other. Dan quit talking and quietly decided he couldn’t do it anymore—he was leaving the campaign. When they woke up the next morning, before he could say anything, Mom apologized. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I really need you.” Dan stayed on. As devoted as he was to our mother, he had the ability to field the relentless attacks on her while keeping his own emotions in check. I don’t know how he held up.

By the skin of our teeth we got through the primary. The grassroots organizing paid off, and the network of volunteers and supporters we built across the state gave us the edge. It was a campaign that radiated intensity and excitement. But of course it was Mom who clinched it. What people remembered when it was time to vote wasn’t so much policy or a position statement; it was how Mom had made them feel. She wasn’t afraid to be who she was, warts and all.

• • •

The general election meant facing Republican candidate Clayton Williams, a Texas oilman and classic sexist pig. Williams had never held public office, and he loved to make crude comments about women. (Sound familiar?) He joked about going across the border to Laredo to get “serviced” by prostitutes, and once told reporters that rape was like bad weather: since you couldn’t do anything about it, you may as well lie back and enjoy it. He was awful. Every chance he got, he’d try to physically intimidate Mom and put her off her game by looming over her or pointing his finger right into her face. My brother once asked how she managed to stay calm when dealing with Williams. “You know,” she said, “my blood pressure drops. I go into cool mode. Here he is, another guy who lives a privileged life and doesn’t give a damn about women. Now I get to expose that to the world. He doesn’t get under my skin any more than the rest of the people I’ve dealt with all my life.”

As the campaign went on, the days got longer and the pace picked up. With Lily in tow, I just kept campaigning, speaking to teachers, union meetings, and students from the Rio Grande border to Texarkana. Even Texas A&M University, known for being conservative, had its own student group, and boy, were they bold. On that campus, simply being a Democrat was gutsy enough, let alone working to elect a progressive Democratic woman. But they wore their “Aggies for Ann” T-shirts with pride. The great homecoming parade incident notwithstanding, Baylor was home to some of our very best organizers, including David Miller, a fearless student who organized volunteer phone banks, rallies, and more.

Ann Richards versus Clayton Williams: He was a classic good old boy who wanted to put women in their place. It didn’t work.

Everywhere I went I made a point to stop by the local paper; in those days there was one in every town. I could drop by, get a picture in the next day’s edition, and talk about Mom. I’d drive up with bumper stickers and yard signs in the backseat, along with a change of clothes and the names of the newspaper editors from the Palestine Daily Herald or the Corsicana Daily Sun. Sometimes I had an appointment, but sometimes I just had to knock and ask, “Is anybody home?”

If I got really lucky, I’d be able to go to the radio station next door and do an impromptu interview. I’d introduce myself: “Hi, I’m Cecile Richards, my mom is running for governor, and I just wanted to stop by and say hello.” More often than not they’d put me on the air right away. It wasn’t like today, where you have to know everything about every issue to go out and speak about a candidate. They didn’t have in-depth questions about health care policy or the rice subsidy; they just wanted to know why Mom was running for governor and what she was like. I was an expert in those areas.

In the middle of it all, I discovered I was pregnant. My doctor called while I was busy campaigning to tell me I’d had an abnormal blood test, which meant I either had a complication or was looking at a multiple birth. I was incredibly anxious. Everyone was busy, but my sister came with me for my follow-up appointment. I was on the exam table, mid-ultrasound, when my doctor looked up and said, “Well, it looks like you’re having twins!” Ellen and I just looked at each other, dumbfounded.

Kirk called me from the East Texas headquarters to see how the appointment had gone, and I gave him the big news. “Ann,” he said, calling Mom over to the phone, “you’re going to want to hear this for yourself!”

Mom was delighted. Later that day, she informed the press that she had just learned she had twin grandbabies on the way. “I told my daughter, ‘Great, you can name them Darryl and Darryl!’ ” she cracked. These were characters on The Bob Newhart Show.

My last months on the campaign I traveled through the state, large as a barge. You haven’t lived until you’ve been on a float for the Gilmer Yamboree, the annual celebration of the yam, eating for three and looking like it too. Every morning I’d hook myself up to a fetal heart rate monitor, which sent readings to my doctor’s office, then go about business as usual. One day Kirk walked into the office to find me plugged into the monitor while shouting into the phone about some urgent situation: “Who’s introducing Mom at the fundraiser in Dallas?” or “The radio station in Lufkin doesn’t have the ads that are supposed to be running!” or “Who can drive to Houston and pick up those four-by-six highway signs?” He told me later he wondered what kind of readings were coming through on the other end. But maybe all the chaos helped prepare my twins for the world they’d inhabit.

The campaign went on through the summer and fall, with polls routinely showing us 20 points behind. Then one night Mom took the stage for a debate with Williams. She turned in a rock-solid performance—it was clear to all in attendance that she had won. Afterward she walked up to him and held out her hand; he looked her in the eye, turned on his heel, and walked away. Mom tried to laugh it off, saying to the person next to her, “Well, that wasn’t very sportsmanlike.” Ironically, after everything else he had done, that was the moment when some people began to question whether he had the temperament to be governor.

Still, come fall, this crude, inexperienced businessman was the favorite to win. Things were looking bleak for us—that is, until he made a gaffe even he couldn’t recover from.

For months one of the major sticking points of the Williams campaign had been his refusal to release his income tax returns, and folks were starting to wonder. Was he hiding shady financial dealings? Had he even paid his taxes? Why wouldn’t he do what years’ worth of candidates had done and disclose his returns? (Does this sound familiar?)

He trotted out every excuse in the book. He even tried to claim that as a successful businessman, his returns were just too long and complicated for the average person to understand. He must have been feeling pretty cocky when, a week before the election, yet another reporter asked why he hadn’t released his taxes. Exasperated, he explained that he always paid his taxes. It was just that one year when he didn’t pay any. That was it. Even he knew he had messed up.

In the days before internet access, before social media, before a million competing narratives, that, with five days left, gave us the opening we needed. We made copy after copy of radio and TV ads that we then ran around the state, Pony Express–style, hoping they would strike a chord with hardworking, taxpaying Texans.

On Election Day, Mom stuck to her usual good luck rituals: she took Lily for a walk around Town Lake in the morning, then got together with her friends for a game of bridge. Her parents came up from Waco and joined us at campaign headquarters, where they sat watching the chaos, a little wide-eyed.

At regular intervals throughout the day—9:00 a.m., noon, and 3:00 p.m.—calls came into the office with precinct reports, letting us know how many people had walked into the local polling place to cast a ballot. If numbers were low, we’d send out more folks to knock on doors and get people to the polls. If numbers were high, we’d send our organizers somewhere else. It was all a question of turnout.

Matthew Dowd, a data expert who knew Texas inside and out, was tracking all the numbers on a massive paper spreadsheet. He had identified a magic number we needed to reach in key precincts—if we could get there, we’d win. All day long we hovered around him, asking for the latest counts. At 7:00 that evening, when they started collecting the ballot boxes from the precincts and taking them to be counted, the calls took on a new urgency.

“How many boxes?” Kirk would ask the person on the other end. A pause. “They’ve got twelve hundred,” he’d shout, and Matthew would write it on the spreadsheet.

Matthew was the first to realize we’d done it, before any of the networks had called the race. He quietly gathered us together and announced, “That’s it. Ann, you won.”

It looked like Matthew was right, but Mom decided not to say anything until she heard from Williams. We went to the hotel where volunteers were gathered, and as Mom was waiting in a stairwell to go onstage, he called to concede.

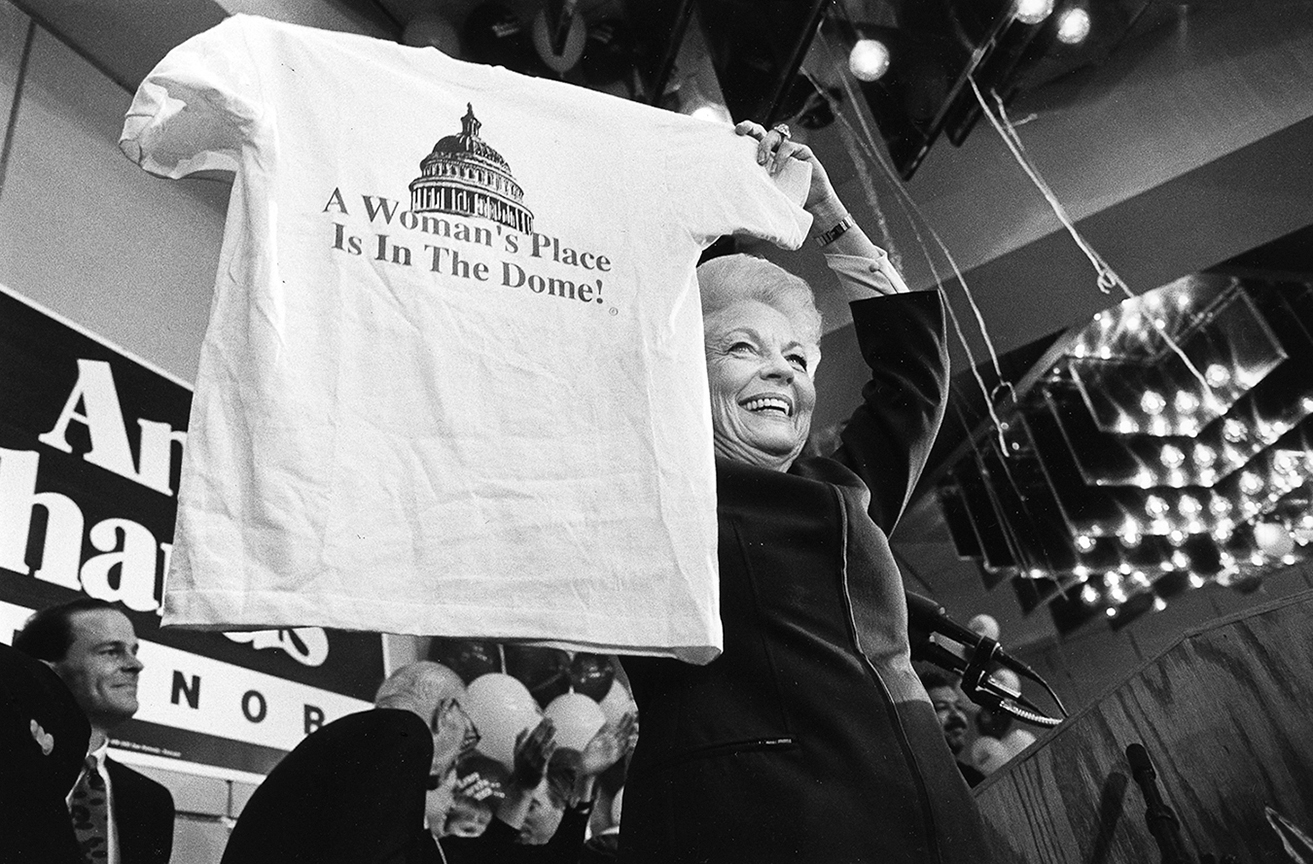

I was eight months pregnant, and as we headed into the supporter rally, I just hoped I wouldn’t go into labor from the excitement of it all. By the time we arrived in the ballroom, people had been partying for hours, and they were worked up into a frenzy. The theme song to Chariots of Fire played when Mom walked onstage, and the place erupted. As we looked up on the TV screen, CBS flashed “Richards Wins Texas Governor’s Race.” The cheers were so loud that Lily, who was in Kirk’s arms, put her hands over her ears. Standing there, basking in her win, Mom held up a T-shirt that someone had handed her: “A Woman’s Place Is In The Dome.”

It was truly an organizers’ victory. We had beaten the odds and elected a divorced, recovering alcoholic, feminist, progressive woman to be governor of Texas. In the end it was the determination of our volunteers that pulled us over the line. We never had a poll showing that we could win—never—and had the election taken place two days earlier or two days later, we probably wouldn’t have. Still, we always believed it was possible.

Over the years plenty of folks have asked me if there are lessons to be learned from Mom’s race. Aside from never putting your toddler in the middle of a college homecoming parade, I can think of two big ones. First, you can’t win unless you compete. For all the people who told Mom she’d never win, she knew that the one way to guarantee that outcome was not to run in the first place. Second, politics at its best is about a lot more than expensive TV ads and polling. It is a contest of wills between folks who are satisfied with how things are and those who are passionate about what could be better. In our case it was a battle between the mostly white, male political establishment desperate to hang on to power, and those who wanted to widen the circle of opportunity for all Texans.

We had built a progressive grassroots army, and they knew that it was their work—every door they had knocked on, every phone call they had made—that put Mom in the governor’s mansion.

• • •

On Inauguration Day we held a march up Congress Avenue to take back the capitol for the people of Texas, and tens of thousands of Texans showed up. It was the kind of sunny day you can get in January in Austin, with an enormous clear blue sky. Women from all across the state—and many more from around the country—came to march. There were student organizers, farmworkers, teachers, you name it. It felt like the people of Texas were back in charge of the state, even if for a fleeting moment. As we marched along, people leaned out the windows of office buildings up and down Congress Avenue and cheered.

Mom’s inaugural speech was one for the books. She welcomed folks to the “new Texas,” and said, “Today we have a vision of a Texas where opportunity knows no race, no gender, no color—a glimpse of what can happen in government if we simply open the doors and let the people in.”

At that point, I had twins at home, and taking care of them was a full-time job. Kirk went to work for Mom, running her political operation across the state. And Mom rolled up her sleeves and got about the business of governing. In Texas the governor’s job isn’t actually all that complicated—you mainly appoint people and approve executions. But Mom was a big believer that you have to make hay while the sun shines, and she used the office to fight for what she believed in. Through the Department of Health she started midnight raids on nursing homes to bust bad actors. She deinstitutionalized thousands of people who had been relegated to state schools and facilities. She began drug and alcohol treatment programs in jails, knowing how many incarcerated people in America are struggling with addiction.

Perhaps most important, she changed the face of state government by appointing more women, people of color, LGBTQ Texans, and regular citizens to boards and commissions than any previous governor had. For the first time there was an environmentalist, Terry Hershey, on the Parks and Wildlife Commission, historically made up of hunters. Ellen Halbert was the first crime victim appointed to serve on the powerful Criminal Justice Board. And Reverend Zan Wesley Holmes Jr. became the first African American ever appointed to the prestigious University of Texas Board of Regents.

Those appointments made a difference, and best of all, they opened the door for a new generation of public servants, many of whom are still involved in government. Ron Kirk, who was Mom’s secretary of state, went on to become mayor of Dallas and, later, a US trade representative for President Obama. Glen Maxey, a prominent LGBTQ activist and campaign organizer, won his race for the state house and became the first openly gay member to serve. Former congresswoman Barbara Jordan was appointed the state ethics adviser and set an entirely new tone for the government of Texas.

Mom was popular as governor, and her Dairy Queen–swirl hairdo made her instantly recognizable. By the time she came up for reelection, there were Ann Richards doppelgängers in cafés all across Texas. She was officially a rock star. But there was nothing she loved more than hiding in the movie theater with a box of popcorn, or taking us all down to the beach in South Padre, where she could shake off the challenges of governing and just be with her friends and family. She took pains to teach Lily how to play gin rummy, instructing her, “Never pick up a face card.”

Mom faced plenty of tough decisions along the way, but one of the toughest was whether to veto a bill that would have allowed people to carry concealed handguns. She received letter after letter from family members who had lost loved ones to gun violence, talked with law enforcement officers across the state, and did her fair share of soul-searching. Ultimately she decided that vetoing the bill was the right thing to do. Arguments for the other side ran the gamut, from fearmongering to the absurd. At one point someone suggested that women needed to keep guns in their handbags in case they were attacked. Mom replied, “I don’t know a single woman who can find a hairbrush in her purse in an emergency, much less a handgun.” She knew her decision was the right one, despite what it might cost her—and in the end it may have cost her a second term.

On election night in 1994 Matthew Dowd, who had called the race the night we won, was the first to realize we had lost to George W. Bush.

It was such an emotional loss. We all felt we’d let our volunteers down, not to mention all those folks who had poured their heart into Mom’s race and her tenure in Austin. For Mom, that was the hardest part; she hated to disappoint anyone. We were overwhelmed with regret, wondering whether, if we’d just done this or that, things would have turned out differently. And of course there were plenty of people lining up to question every decision. It would take months before we realized we had been part of a wave election and a watershed moment for politics in America.

Just like that, Mom had gone from catapulting onto the national scene to feeling lower than low. Ironically she was the most pragmatic of all of us: she knew that beating Bush was going to be harder than most people thought. She was a hard-nosed political realist who knew beating Williams had taken not only our hard work but also his own mistakes. Bush never opened the door in the same way.

Kirk helped pull together meetings in every part of the state to get all the volunteers together and encourage them to stay the course and even think about running themselves. Meanwhile Mom was focused on the staff of her administration, trying to help them get jobs. And of course we had to figure out how to pay off the campaign debt. It was a heartbreaking exercise, so different from what we’d experienced four years earlier.

After the loss the whole family went down to South Padre Island, fantasizing that if we just cut the state in two, Mom could be the governor of South Texas, which she had won handily. Lily, who was seven by then, and had campaigned like a pro, turned to Mom and asked, “Does this mean you don’t have a job anymore?”

In classic Ann Richards fashion, Mom replied, “Honey, this means everybody you know doesn’t have a job.”

But she was still a national icon, and not long after the election she got a call from Frito-Lay to see if she would appear in a Super Bowl ad with her friend, the former governor of New York Mario Cuomo. Like Mom, Governor Cuomo had also lost his reelection bid that year. It sounded crazy, but they would get paid a lot for sitting on a couch, eating Doritos.

I encouraged her to do it. The ad was hilarious and showed all over the country during halftime. A few weeks later Mom and I were in an elevator in New York, and I heard a woman behind me whisper to her friend, “That woman with the big hair—she used to be the governor of Texas!”

Her friend corrected her: “Nope, that’s the lady in the Doritos commercial.”

As an organizer, that was a moment of revelation: maybe instead of running political ads against Bush, we should have just been running Doritos commercials. Apparently those were breaking through in a way we never could. In fact, afterward a poll showed that most Americans could name only three governors: Ann Richards, Mario Cuomo, and their own.

• • •

We were picking ourselves up from the loss and packing up for Mom to move out of the governor’s mansion in January when an invitation came from Carlos Salinas, the outgoing president of Mexico, for the inauguration of the newly elected Ernesto Zedillo. As governor, Mom had worked to build stronger Texas-Mexico relations. Salinas was popular and had brought renewed economic prosperity to the country. (Later it was discovered that he had presided over a huge corruption network, falsely inflated the peso, created a massive financial crisis, and even had someone murdered in the process. But we didn’t know that then.)

I begged Mom to go and to take me with her. Just being invited proved what I knew in my heart: that she was more than a former governor of Texas; she was on the national and international scene. She lost the race, but they had invited her anyway. She had ideas, she had drive, and people still saw her as a leader. So she agreed, and we headed off to what turned out to be the first of many memorable adventures together around the world.

The night promised to be a fabulous gathering of Latin American leaders, and it did not disappoint. The apex of the trip was a dinner at Los Pinos, the official residence of the president. It was the most spectacularly beautiful night I can remember. Murals by Diego Rivera covered the walls, mariachi bands played, and the tables held towers of fruit: pomegranates, oranges, limes, lemons.

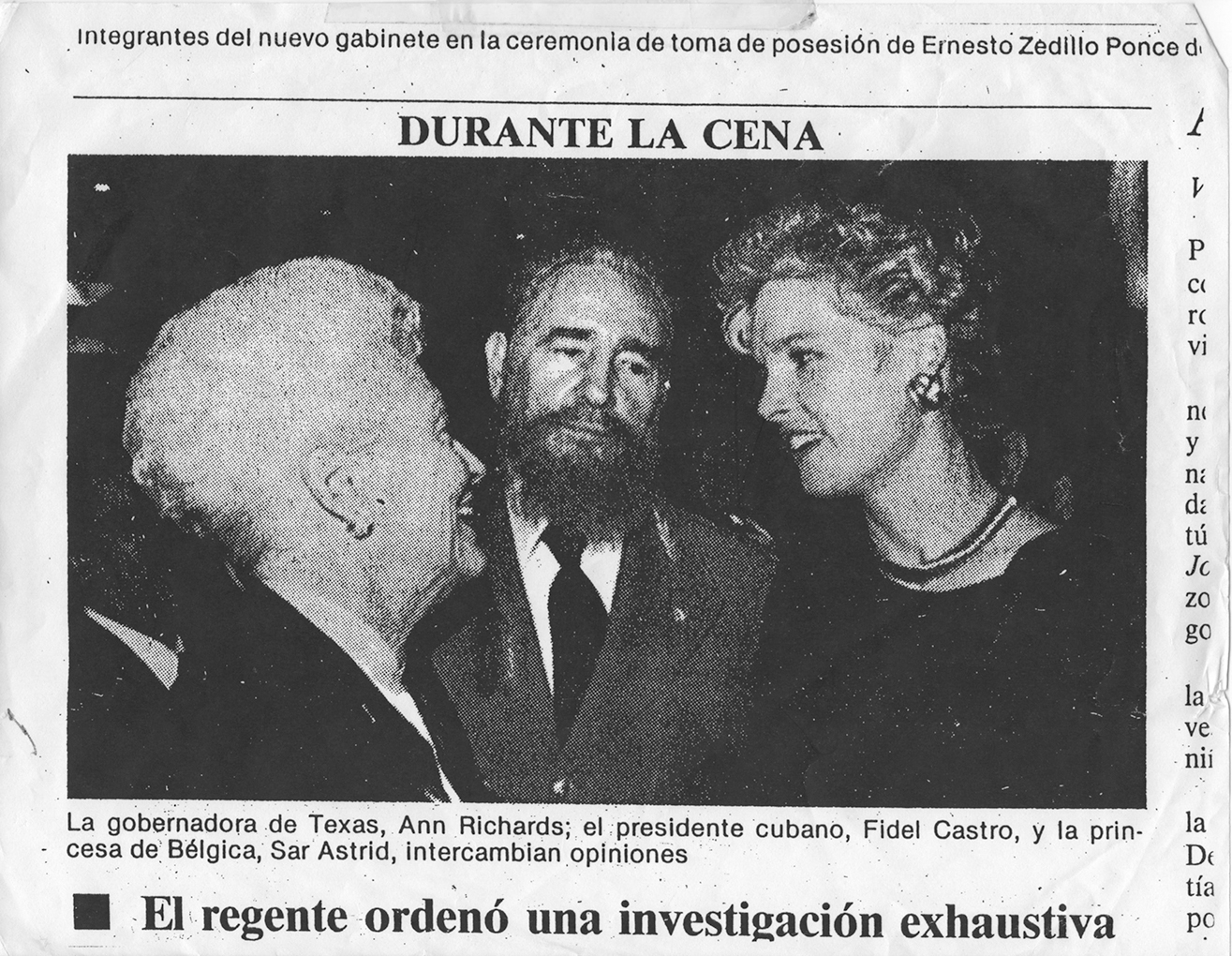

Presidents from across the continent were there, but the person everyone wanted to meet was Fidel Castro, who was attending in full military regalia. Practically no one in America had ever seen or met him. When the dinner was breaking up, I found Mom and insisted we had to at least meet Castro. She was horrified. “If I go up to Fidel Castro, it’s going to be splashed on the front page of the Dallas Morning News, and God knows where else! I don’t have a job, Cecile, and that will make it even harder to get one.”

“Mom, if you don’t do it, you will always wonder, What if? And you just won’t be able to live with that.” I was channeling Ann Richards, and she knew it. I was determined, and so, on the way out, we muscled our way over to say hello.

“Gobernadora Richards!” Castro exclaimed, and he gave her a big abrazo. Whatever else he was, the man had charm.

Sure enough, the next day in the Mexico City paper a big photo appeared of Mom, Castro, and me—though I’m misidentified as Princess Astrid of Belgium (maybe that’s how I got into the dinner after all). Thankfully, the Dallas Morning News missed the story, but that photo is still one of my prized possessions.

Now that Mom was liberated from being governor, she took advantage of other opportunities that came her way. She was making up for lost time. We traveled together to all seven continents. She was genuinely curious to see the world and to experience everything she could for herself.

As much as we tried to make the most of it, the election was a brutal loss. Beyond the pain and hurt I felt on a personal level, it was recognition that the state I loved was not the progressive home I thought we were building. Something was happening, and it was about more than Mom’s election loss.

I’d had inklings of this during the campaign. A few weeks before the election, I was sent to hand out Ann Richards material at a plant gate in Beaumont, a place I knew well, since it was the scene of the Schlesinger nursing home strike years earlier. Of all the folks on the campaign, I was the logical one to go—this was my territory.

The general idea was that you showed up early, as folks were going to work, and gave them a campaign flyer with Mom’s photo and a reminder to vote on Election Day. It was a way to create a sense of urgency and enthusiasm as we were getting down to the wire—not the most intellectually stimulating task, but a lot of organizing really comes down to hard, even thankless work. I liked doing it because I learned a lot from seeing hundreds of people and hearing what was on their minds.

What I heard that day, as I stood outside the gates, was frightening. Grown men in hard hats with union stickers on their lunch pails cursed and snarled at me. “There is no way I’m going to vote for Ann Richards or any other left-winger who wants to take away my guns!” Or a variation: “She’s a baby-killer.” It was as if they were reading from a script—and a familiar one at that.

We’d heard this kind of rhetoric from our opponents plenty of times before. The National Rifle Association had always hated Mom, even more so since the concealed carry veto, and we knew they were out for her. And the antichoice folks were after her because she was unapologetic in her support for abortion rights—no surprise there. But these union guys? They were our people! They were the same folks who had carried her to victory four years earlier, and by any measure Mom had done right by working people and built economic opportunity in Texas. She had stood up for collective bargaining, helped enforce laws that guaranteed union wages on public works projects, and more. What was going on?

At the height of the election we knew that Bush’s political strategists were injecting homophobia into the campaign. Many gay and lesbian leaders were openly and proudly serving in Mom’s administration, and that opened the door for yet another disgusting line of attacks. At one point Rick Perry, then a candidate for lieutenant governor, even accused Mom of being supported by “Hollywood thespians,” a nod and a wink to his own grotesque ignorance and that of his audience.

This kind of political character assassination had been commonplace for years. But this time the rumors and hostility were actually gaining traction. The effect was not only to defeat Mom and several candidates across the state, but also to cement the ownership of the extreme right wing of the Texas Republican Party, which carries on to this day. Political hack Perry later became governor and went on to create what has become one of the most reactionary state governments in the country (before his time on Dancing with the Stars, of course). And George W. Bush? He was elected president of the United States. But that would all come later.

Talk about taking risks: Mom left office with no job, no house, no car, and definitely no one to fall back on. As she said, she was the ultimate ex: ex-wife, ex-governor, and ex-politician. She’d had plenty of defeats and overcome them all. Fortunately she knew that being governor had been her job, not her entire identity, and she was determined to look forward, not back. Her motto was “No regrets.”

She hustled up a job pretty quickly. As she told us kids, “I do not want to end up living in Ellen’s driveway in a trailer.” Poverty had been such a part of her upbringing that she was determined not to end up back where she had started. That’s how she found herself working as a lobbyist and consultant for a Washington law firm, translating legalese into plainspoken English along with teaching lawyers how government works. Her skills were in high demand.

The rest of us were at sea. Kirk went back into union organizing, and everyone else hit the pavement. Austin was the kind of town where there were only a few decent progressive jobs, and folks died before giving them up. Which meant there was a glut of talented do-gooders hoping to find what was next.

I had to work, but I couldn’t imagine going back into organizing with the labor movement. I had three small kids, and as my organizer friend Madeline Talbott used to say, “I’m too old to door-knock, too young to die!”

Given the total wipeout of the Democratic Party in Texas that election, there was an opening to run for party chair, and folks asked me to think about it. As an organizing challenge, it was certainly compelling: there was enormous rebuilding to do. But it was unclear whether the Democratic Party, which had plenty of baggage, was ready for radical change.

Most of all, I just couldn’t stop thinking about my experience in Beaumont. I remembered an email I’d gotten a few weeks before the election from someone in California, telling me that we better be on the lookout for a newly formed group called the Christian Coalition. She said they were organizing through churches, using extreme social issues and rhetoric to boost turnout in the elections. At the time it had sounded like a lot of other conspiracy theories that show up in the last days of an election. I figured that, at any rate, it was too late in the game to do much about it.

Despite the name, the Christian Coalition was not a religious organization. It was a political organization, designed to elect candidates and build political power. Across the country they had quietly launched a targeted culture war to demonize politicians who supported women’s rights, LGBTQ rights, and gun safety reform—casting supposed “God-fearing” candidates against everyone else.

Up to that point the business community had led Republicans in Texas and pretty much everywhere else. While they had supporters among the Far Right, that element had never dominated the party, and most of the Republican issues related to lowering taxes and smaller government. But in 1994, the year Mom lost, the party took a hard right turn. The Newt Gingrich “Contract with America,” helped elect dozens of ultraconservative members to Congress. This was bigger than Mom. In fact it was bigger than any of us.

As I weighed what to do next, I thought of a question a reporter had asked Mom after she lost the election: “What would you have done differently if you knew you were going to be a one-term governor?” She had just grinned and answered, “Oh, I probably would have raised more hell.” I decided it was time for me to start raising some hell of my own.

Ann Richards.” Kirk had his buddies in the labor movement print them and pass them out—it was such a boost. And then, of course, she gave the speech of a lifetime. “Twelve years ago, Barbara Jordan, another Texas woman, made the keynote address to this convention, and two women in about 160 years is about par for the course,” she began. “But if you give us a chance, we can perform. After all, Ginger Rogers did everything that Fred Astaire did. She just did it backwards and in high heels!”

Ann Richards.” Kirk had his buddies in the labor movement print them and pass them out—it was such a boost. And then, of course, she gave the speech of a lifetime. “Twelve years ago, Barbara Jordan, another Texas woman, made the keynote address to this convention, and two women in about 160 years is about par for the course,” she began. “But if you give us a chance, we can perform. After all, Ginger Rogers did everything that Fred Astaire did. She just did it backwards and in high heels!”