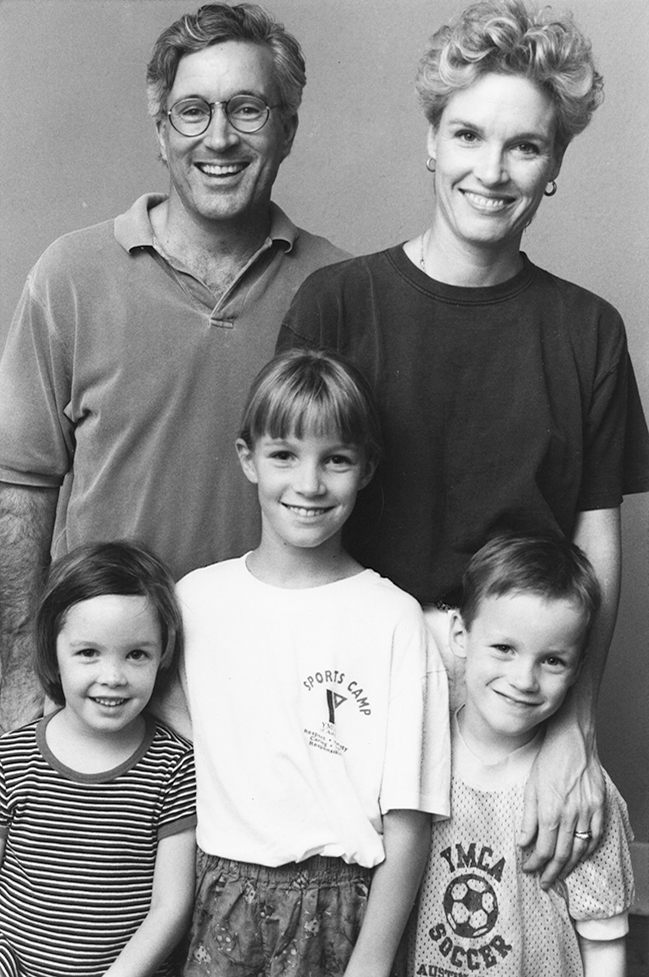

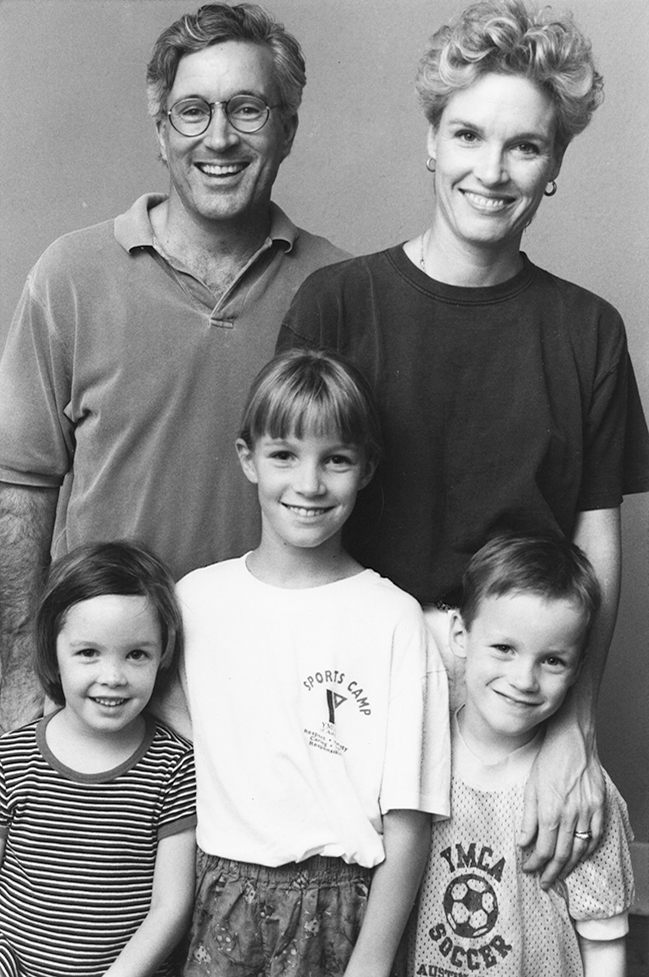

Austin, 1995, with the first volunteers for the Texas Freedom Network.

“We believe that Langston Hughes’s poems must be removed from the books, as he was a known Communist,” declared a voice from the front of the room.

It was hour 2 of the State Board of Education meeting, and I was riveted. This rather bland-sounding body was responsible for approving textbooks and setting curriculum standards for more than three million public school kids across Texas. Though it was 1995, I felt like I had traveled back in time to the 1950s.

A new day had dawned in Texas politics after the November election. The same right-wing agenda that swept George W. Bush into the governor’s mansion also changed the balance of power on the fifteen-member state board of education, with three new members that one newspaper called representatives of “the sex-obsessed shock troops of the religious right.”

A week earlier I’d been with my friend Harriet Peppel, who had been following the state board of education. She turned to me with her eyes as big as saucers and said, “Cecile, you are not going to believe it. The only way to understand what is going on is to come with me to the next public meeting.”

Now we were there and I could barely comprehend what I was hearing. I scanned the room, looking for allies. The audience was disappointingly sparse. There were some representatives of the teachers’ organizations and the superintendents and school boards. But most of those in attendance were lobbyists for the textbook industry, and they were simply trying to figure out how to sell books. As one of those lobbyists later told me, “I can hit a curve ball, a slider, or a fast ball—I just have to know what game we’re playing.” In other words, he wasn’t going to fight these nuts; he was going to make sure that the book publishers deleted whatever the right wing objected to so that they had the best chance of getting their books approved for the lucrative Texas textbook market.

The most active participants in the audience were Melvin and Norma Gabler, an East Texas couple who read every single textbook put forward for adoption and wrote up page after page of complaints. They objected not only to the poems of the great Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes but also to anything that smacked of equal rights for women, environmentalism, or negative portrayals of slavery, to name just a few.

When I couldn’t take any more, I ripped a page out of my notebook and passed a note to Harriet. It read, simply, “It’s so much worse than I believed!”

I had started reading up on the Christian Coalition and learned a lot from Harriet, who was working for People for the American Way, a group started by the sitcom producer and writer Norman Lear to monitor the activities of the right wing.

Getting up to speed on the Christian Coalition was like running down a rabbit hole. The more I discovered, the more it became clear that none of what was happening at the State Board of Education was a one-off. Ideas that were once relegated to the wackiest late-night televangelists had now moved into the realm of politics. Pat Robertson’s preaching that feminism was “a socialist, anti-family political movement that encourages women to leave their husbands, kill their children, practice witchcraft, destroy capitalism, and become lesbians” summed up the philosophy of the Christian Coalition. Reverend Jerry Falwell made the case directly, evangelizing, “I hope I live to see the day when, as in the early days of our country, we won’t have any public schools. The churches will have taken them over again and Christians will be running them.”

The worst part was that they were well on their way to achieving that goal. One of the most under-the-radar efforts in the Texas elections was the targeting of two mainstream State Board of Education members, Mary Perkins and Patsy Johnson, who had devoted their lives to public schools. Like Mom, Patsy and Mary were both defeated in November, the victims of a truly vicious direct-mail campaign. The headline of the most infamous mailing sent to voters screamed, “Is this what you want your children to see?,” with a large photo of two naked men embracing and kissing. It repeated scandalous claims by the Christian Coalition, including that the State Board of Education was peddling instructions in gay sex to high school students. Mary and Patsy were replaced by two Christian Coalition–supported candidates, who proceeded to take on every curriculum and textbook issue with a vengeance. At this point I had three kids in the public schools. It was alarming to think that this crew of far-right political strategists wanted to determine what my kids were reading and studying—let alone decide what went in textbooks across Texas and across the country.

I was on fire. I wanted to turn to people and say, “Does everybody know what’s going on? Isn’t somebody going to do something about this?”

Then I realized: What if that somebody was me? I’d never started anything other than the odd food co-op and antipollution group, but I realized that if I didn’t do it, it probably wasn’t going to happen.

Here, dear reader, is something worth considering before committing to a spouse or partner: there are only certain people who would hear that and say, “Hey, that’s great! We have no savings and no house and three kids in school, but do your dream!” That’s Kirk. I’ve had a lot of harebrained schemes in my life, and he’s gone along with every one of them.

Without any idea how to start an organization, I made up a name, the Texas Freedom Alliance, and typed up a mission statement. I was going to organize Texans in support of public education and religious liberty. I found a group in Washington, the Alliance for Justice, that helped folks start nonprofits. (If you’re thinking about branching out on your own, they’re still a great place to start.)

We started out in my living room, then found someone to temporarily donate a tiny office. I convinced Peter Shakow, a friend from Mom’s campaign, to help out for the first few months. My grandmother Nona wrote our first check, for $100. It has to be the only check she ever wrote in her life for that much money. My kids were some of our earliest volunteers, helping put together flyers and mailing them out to people we knew. My sister held the first house party, and we were off.

Austin, 1995, with the first volunteers for the Texas Freedom Network.

I had just the beginnings of a plan, but every time I had to explain it to someone, it got a little bit clearer. Our new organization wasn’t rolling in money, but we were rolling in opportunity—speaking to education groups, teachers, anybody. A local synagogue invited me to come and speak to their congregation, and that is where we got the first non-family-member donation and our first two non-family volunteers, Ethyl and Manny Rosenblatt. They were tremendous, and didn’t care if we were making it up as we went along. Like a lot of other Texans, they were frustrated with the rightward political drift and looking for a place to pitch in.

Our unofficial motto was “Wherever two or more are gathered together!” Harriet and I drove all over Texas and, fortunately, joined forces with Janis Pinelli, another former Ann Richards volunteer. Not only did Janis have a car big enough for all three of us to ride around (and change clothes) in; she was also a licensed CPA and helped me figure out how to set up the books and create a board of directors.

After meeting Mary Perkins and Patsy Johnson, the two Board of Education members who had been ousted, we began to connect with others who had similar horror stories at the local level, including one close to home.

Round Rock, Texas, is a suburb of Austin, known for having an excellent public school system. People would move there and commute to Austin just so their kids could go to the Round Rock public schools. That made them a prime target for the Right. The same families that had come to Round Rock for the schools were now watching in horror as the superintendent was fired, school board members were tossed out, and reading lists were rewritten. Up to that point the parents we talked to wouldn’t have been at the top of anybody’s list to become political activists, but now they were angry and determined to fight back against what was happening.

Coincidentally Round Rock had a well-known, well-respected young adult author right there in the district: Louis Sachar. Louis was a kindly, older, soft-spoken guy, and one of his books, The Boy Who Lost His Face, was on a school reading list. But the newly elected school board members banned the book, claiming it was profane. Louis would go on to win the Newbery Medal for his book Holes, which was made into a very popular young adult movie. But here in his hometown, the local school board was trying to prevent young people from reading his work.

The craziness of what was happening in Round Rock was so profound, combined with the shenanigans in other suburban communities and at the State Board, that we decided to make a documentary. Campaign friends Mark McKinnon and Margie Becker made it for next to nothing, and we then had an excuse to speak to groups. We showed them this ten-minute film, then gave our spiel and tried to recruit members.

Folks were definitely starting to take notice, and not just our supporters. I arrived at the office one morning to get a certified letter from the attorney of none other than Colonel Oliver North, infamous for having illegally funded the contras during the Nicaraguan Civil War. Apparently North’s right-wing organization was called the Freedom Alliance, and his attorney threatened that we must “cease and desist” using our name lest the two be confused.

It was incredible! Our scrappy group in Texas was on the radar of the Right Wing! Even better, being threatened by Oliver North gave us a great chance to start a statewide renaming contest and get some free press. That is how we became the Texas Freedom Network and picked up some new supporters in the process.

It was exciting and fulfilling to build something from nothing—especially something that might actually make a difference. Everywhere we went we met people who were eager to help. By bringing together teachers, PTA activists, and progressives across the state, our motley crew began to stand up for public schools. We did battle at textbook hearings, bringing scientists to testify on the importance of accurate science books, and blasting out the most outrageous statements by board members to the press. At one point some board members wanted to remove a photograph from a textbook of a nicely dressed woman walking out the door of her house, carrying a briefcase and waving to her family, saying it encouraged women to leave their children. We tipped off the Today show, and it made for great television.

We also started organizing an unexpected group: religious leaders. What was being done in the name of religion was so appalling that one of the most common bumper stickers at the time read, “God, please protect me from your followers.” We started the Texas Faith Network with Baptist preachers who had been fighting the takeover of the southern Baptist Convention by the Far Right. At that point the Texas Baptist Convention was led by mainstream preachers who saw their faith as fundamentally and critically disconnected from the government.

For a statewide convention of Texas public school teachers, I had asked one of our clergy leaders to address the growing challenges to our public schools. Reverend Larry Bethune of University Baptist Church in Austin was not only an eloquent orator; what he said was relevant to many teachers who were deeply religious and involved in their church. Afterward a woman came up to him with tears in her eyes and said, “I’m so glad you were here. I’m a Christian and a public school teacher, and it was so important to hear a man of faith tell me that what I do is good and not the work of the devil.”

One of the most extraordinary religious leaders I got to know was Don Sinclair of the Bering Memorial United Methodist Church in Houston. Reverend Sinclair was at the end of his career, and his gentle, grandfatherly countenance immediately put people at ease, even when he was taking on his harshest critics. One day, sitting with him at a radio station where I had asked him to do a live interview, I could hear the difference it made to have him, rather than me, on the airwaves. No one could out-scripture Don Sinclair.

The clergy became so critical to our organizing efforts that they were in demand in the press, speaking out about everything from LGBTQ rights to support for public education. Bill Davis, a Catholic priest from Houston, would ask me before such events, “Are we supposed to wear our sin-fighting suits?” Bill always came in his collar unless otherwise notified.

Along the way I made my fair share of mistakes and learned just how hard it can be to get an organization off the ground. It’s one thing to raise money for a candidate; it’s another to fundraise for your own organization. I soon learned the truth of the adage “If you want money, ask someone for advice. If you want advice, ask someone for money.” There were plenty of folks (especially men) who didn’t want to write a check but were happy to tell me how they would have done it.

That fall, we were out of cash. Harriet and Janis and I put thousands of miles on Janis’s Buick looking for anyone to hold a fundraiser. We had heard about a woman in Dallas who seemed keen, so we piled in Janis’s car and drove four hours just to see her. We met on the sun porch of her lovely North Dallas home. The backyard looked like it went on for days, and the whole place screamed “fundraising party” to me. We were desperate and ready to pull something together right then.

“I really love what you are doing,” she said. “It is so urgent that we stand up to anyone who would be trying to harm the public schools.” (Though from her expansive home and neighborhood, it seemed unlikely anyone in her immediate family had any personal familiarity with the public schools.) “I would love to do something next spring. That’s when the azaleas are in bloom, and the yard really looks its best.”

My heart fell into my stomach. Next spring? That was six months away. It may as well have been next century. We needed someone to help now—like yesterday. Janis and Harriet and I stopped by the Dairy Queen on the road back to Austin to drown our sorrows in chocolate dip cones. An eight-hour round-trip drive to Dallas just to be pushed off to next spring. I felt lower than a snake. Still, I didn’t regret making the trip. We were a start-up and desperate, and this was what it took to build something from scratch. On the way home I lamented, “Coming across a wealthy person who agrees with what we’re doing is like finding a needle in a haystack! It would be easier to go find a donor, and ask them what kind of organization they want us to form!”

TFN was barely six months old when a call came that changed our fortunes and our future. It was Halloween, and I was in costume. I’d just come back from the kids’ elementary school, having learned from my mother that there’s nothing like embarrassing your children on Halloween. I was wearing my Maleficent headdress with entwined horns and a sweeping black cape, with black and purple eye makeup, when the phone rang at the TFN office.

“I’m calling for Cecile, from the Leland Fikes Foundation in Dallas,” said the voice on the other end, who turned out to be Nancy Solana. Suddenly I remembered that one of the many requests for support we’d sent had been to the Fikes Foundation. I didn’t know them, but a friend had said to give them a try. I took off my horns and quickly switched from my alter ego to say yes, this was she.

“We received your grant proposal, and I just have one question: What font did you use?”

Was this a trick question? Crazily enough, I knew. It was Footlight MT Bold. I’ve always had a thing for fonts, and this was before the days when the internet gave you a million options. It was important to me that anything we sent out looked good, and the font I’d picked was clean and classy. That’s the beauty of running your own organization: you get to weigh in on everything from the logo to how to arrange the chairs at a meeting. I’d learned from Mom that there were a million ways to do something, but only one right way. So I told her.

“Great!” she said. “I love that font. I want to use it. Oh, and by the way, the foundation approved your grant. We’ll send you the paperwork and have a check to you in a couple of weeks.”

“YESSSS!” I screamed at the office. This was our first legitimate grant. It meant we could make payroll through the end of the year, and maybe even be on the road to survival. Lee and Amy Fikes, the most unassuming, wonderful people, became our strongest supporters. That phone call gave me the confidence that we could keep going.

There was no guarantee when I started the Texas Freedom Network in my living room months earlier that it would ever make it. But if I hadn’t given it a shot, I would have spent the rest of my life wondering what might have been. I stayed for three years and built it into a small but mighty organization.

Eventually, though, I started to feel that it was time to move on. Kirk and I were ready to leave town for the next challenge. It was hard being in Texas after Mom’s loss, which felt like a betrayal, and we’d stuck it out as long as we could. I guess I should have realized how angry I was when a guy came to mow my lawn, long after the election. He was driving a beat-up truck with an old bumper sticker on the back from the days when Mom was in office: Gee, I Sure Miss Governor Clements (the jerk who was governor before Mom). I walked up to him and said, “I am going to pay you, but you’ll have to leave.” He looked dumbfounded. “Why?” he asked. “I haven’t even gotten out my mower.” “I just can’t have you out in front of my house,” I replied. It was then I knew I hadn’t gotten over it.

When Kirk got an opportunity to go to Washington for the AFL-CIO, it seemed like a good place to make a new start. I’d started TFN from scratch and built it to a point where I knew someone else could take over. We had an office, staff, and (hallelujah!) a year’s budget in the bank. Fortunately I knew a brilliant organizer, a Texan named Samantha Smoot, who was out in California working for EMILY’s List. Somehow I convinced her that running TFN was a great opportunity, and thank God the board agreed. Sam moved back to Austin and took the TFN to the next level. Years later she handed it back to Kathy Miller, our original deputy director, who made it her own. Today the Texas Freedom Network is a key force for good in the fight for public school funding, LGBTQ rights, and immigrant and voting rights. And best of all, they’ve begun training hundreds of young leaders across the state. That’s another important lesson: Once you leave, let go! Sam and Kathy each had their own vision, and the organization changed and grew with their leadership. It has been wonderful to see what they have built.

• • •

If there’s one common theme that runs throughout my life, it’s strong, kick-ass women. My grandmothers, each in their own very different ways, were tough and pioneering. My mother broke the mold. And at every job I’ve ever had, I’ve tried to work for someone who could teach me something—and more often than not, that someone has been a woman. For all of these inspiring women, it wasn’t as if the world just threw open the door and invited them in. Each one has been a disrupter in one way or another. They’ve made trouble, broken the rules, and challenged authority—and no one more than the US House Democratic leader and former speaker Nancy Pelosi.

I’d been living in Washington for a while when my friend Gina Glantz, who had tried to hire me to work on Bill Bradley’s campaign for president, called with another crazy idea. Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi had just been elected Democratic whip—the highest-ranking woman ever to serve in Congress—and Gina saw her rise as a huge opportunity. Gina had the unerring ability to peek around the corner and imagine what could be, instead of just seeing what was. And she was right about Nancy.

“Nancy will have her pick of talented folks who come from Capitol Hill,” Gina explained, “but she needs someone who can help make sure her agenda is understood outside of Washington. She understands organizing and wants someone who can bridge the gap between the grassroots out in the states and what is going on in the Capitol.”

Up until that point it had never occurred to me to work on the Hill. At the time I was working for Ted Turner and Jane Fonda, traveling around the country and giving away money from their foundation to groups working for reproductive rights. It was a great job. But rather than funding other people’s work, I wanted to be doing the work myself.

I had not the foggiest idea what Gina was actually proposing—she was describing a position that didn’t yet exist, and I had never even met Nancy Pelosi. The people I did know on the Hill had all been there for years and knew the ropes. That whole world was a mystery to me. But George W. Bush was in the White House by then, and it seemed like we were settling in for a rough few years. I wanted to be somewhere I could have a greater impact, so I decided to give it a try.

I interviewed with George Crawford, a Capitol Hill veteran who was putting together Nancy’s staff. The whole time, I was thinking, This is crazy—why would they hire me when anyone would kill for this job? But George seemed to think my knowledge of the progressive organizing world would come in handy, and he brought me on, along with the brainiest bunch of people I’ve ever worked with.

We worked cheek to jowl in a small office; you couldn’t so much as sharpen your pencil without everyone else noticing. I was constantly aware of my shortcomings, though none of my colleagues ever made me feel that way. I was in awe of them; they seemed to know everything about government, from the requirements of a “motion to recommit” to who had been where in the last race for speaker of the House.

No one gets to be the highest ranking woman in the history of our country without being enormously driven and willing to upset every convention, including the notion that men are forever destined to be in charge. As Democratic whip, Nancy was second in command to the Democratic leader, Congressman Dick Gephardt from Missouri. She was also the ranking Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee and part of the so-called Gang of Eight—the group of members of Congress who received private intelligence briefings from the CIA, Defense Department, State Department, and the White House. She was intimately aware of all foreign policy issues, and on top of that, she was an incredibly hard worker. She read every briefing memo, every policy paper, every headline—and expected her staff to do the same. Somehow she managed not only to beat us all to work in the morning but also to keep on top of all five of her kids, their spouses, and every grandkid. She would implore us at the end of the day, “Go home and see your family! Get out!,” even though she never did.

In the fall of 2002, just a few months after I started, President Bush declared that intelligence reports showed that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, and he wanted a vote by Congress approving military action. Capitol Hill began a contentious debate on the proposal, but not long after, Gephardt appeared with Bush in the Rose Garden and endorsed the president’s plan to go to war. I was angry that the Democrats were in any way going to support us going to war with Iraq. It made me wonder whether working in Congress was even a good idea; I had been used to speaking my mind, not toeing a party line.

The topic had consumed our office, and I was pretty sure that Nancy was not at all convinced that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. She took a declaration of war seriously, as all members of Congress should. As she often reminded us, it was perhaps the most important vote you could ever take. I was still new, and I didn’t work on intelligence issues, so I was an observer, like everyone else, waiting to see what would happen.

A couple of days later, at the next meeting of the House Democratic Caucus, I got my answer. Each week the entire caucus would cram into a tiny basement meeting room and get their marching orders for the week: what’s coming up, what they needed to know. Gephardt defended the resolution to support the Iraq war. Then Nancy got up to speak.

“I am aware of all the intelligence reports,” she said. “I strongly believe there is not adequate rationale to support this war with Iraq, and I will vote against it.”

I was standing in the back of the room with the others from our office, and I was stunned. I knew that Nancy was strongly against the war, but she had just spoken against the position of the Democratic leader and of the president. This was a closed meeting: no press and very few staff. She didn’t do this for attention or to be a heroine; she did it because she genuinely believed it was the right thing to do. It seemed like a staggering act of courage. I was so proud to work for her that day.

Here’s the thing about Nancy Pelosi: she backed up those inspiring words with action. She provided information and helped persuade other members of Congress that this was critically important. By the time of the vote on October 11, 2002, she had convinced a majority of Democrats in the House to vote against the war. That was no small feat, considering that the majority of Democrats in the Senate voted for it.

That was the Nancy Pelosi I have experienced time and time again, who knows her mind and does not back down. I remember feeling I would do anything to make sure people in the country knew the battles she was taking on. It was difficult to convey the complexity and importance of what was happening on the Hill, but that became my main assignment for the next several months. It was a puzzle: How could people who lived in Ohio or West Texas be made aware of the fight the Democrats in Congress were waging back in Washington?

Even though at times I felt like I was in over my head, I also felt at home working for Nancy. She reminded me so much of Mom. Both had raised kids and done what society expected of them before they had the chance to become political leaders. Both were impatient to make sure that the next generation of women did not have to wait so long.

My mother said often, “Life isn’t fair, but government should be.” There are countless stories of women who run for office because they believe exactly that—like Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky of Illinois, who got her start as a young housewife leading a campaign to put expiration dates on food in the grocery store, and Congresswoman Stephanie Murphy of Florida, who was inspired to challenge an NRA-endorsed incumbent after the 2016 Pulse nightclub massacre. Women aren’t usually in it for the glory; they’re in it to get something done.

And it’s a good thing they are, because Congress on the whole is a macho, “guys hanging out with guys” kind of place. When Barbara Boxer was elected to the US Senate, there wasn’t even a women’s bathroom near the Senate floor—and that was in 1993! For many women in Congress, once they leave work for the day, they’re back at their house, doing homework with their kids or catching up on the legislation they want to pass. But the men, even with their partisan differences, drink together, work out together; in Texas they hunt and fish together. There is no harder social circle to break into. Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, a Democrat, often boasts of working out in the congressional gym early in the morning and catching up with his Republican counterparts over the free weights or in the locker room. How are Senators Kamala Harris and Kirsten Gillibrand supposed to pull that off?

Like a lot of women in office, Nancy didn’t get where she is because someone picked her; she got there because she decided to run and then was determined to succeed. She knew the caucus intimately, knew the members’ districts, and understood the difference between what Jack Murtha, a Vietnam veteran from Pennsylvania, needed for his constituents and what John Spratt from South Carolina needed for his. She usually knew the members’ spouses, their kids, and what issues they were passionate about. She fundamentally understood how to connect with her colleagues as people, and she showed them every day how much she cared about them.

When Congressman Gephardt retired, Nancy decided to run for Democratic leader, the highest-ranking position for the party in the minority. Even though she had served as whip, her election was not a sure thing. She ran against Texan Martin Frost, a fellow progressive, and a formidable opponent. Nancy had strong support from women in the House, but there weren’t nearly enough of them to build a majority.

I watched in awe as Nancy designed her campaign plan and executed it like clockwork. Morning, noon, and night she did outreach to caucus members and got commitments to support her. It was a race with plenty of plot twists. After a contentious year-long battle, with just days before the vote, Congressman Frost realized he couldn’t win and dropped out. Young Harold Ford Jr. of Tennessee jumped in. But Nancy just kept at it. Three of us in her office were responsible for being able to account for every member of the House on the day of the secret ballot. I studied the photographs and was stunned again at how many white men were in our caucus. It was another reminder of how tough the odds were against Nancy.

But when they counted the votes, Nancy had won. Like Mom’s inauguration, it was a day I’ll never forget: the first woman ever to lead her party in Congress! And wouldn’t you know, when they did the final tally of the votes, the result was exactly what Nancy had predicted. She knew something I had learned early on in union organizing: Assume any wavering vote is a no until you get a firm commitment. It seems like a simple thing, but this is one of Nancy’s most important skills: whether as speaker or as minority leader, she has been able to hold her caucus together and predict where the votes are. Time and time again, no matter which party is in charge of Congress, it’s usually Nancy who can round up the Democratic votes needed to pass crucial legislation.

Nancy has an incredible grasp of history and an enormous respect for the institutions of government and Congress. The day she was elected Democratic leader, she also became part of the congressional leadership made up of the two highest-ranking members of each party in the House and Senate. As is customary, the president invited the group to the White House. When Nancy came to work the next day, she was still processing what her election meant. Back in her offices on the second floor of the Capitol, she described the emotion of going to the meeting with the president. I’ve never forgotten what she told us that day. “I was so aware, walking through the gates and into the White House, of the hard work and sacrifice of prior generations of women,” she said. “The suffragists, and all the women who broke barriers. As I sat at the table with the president and the top leaders of Congress, I realized that it was the very first time a woman had ever been at this table. It was as if women from throughout history, women who had made this possible, were there with me. And all around me, I felt their presence.”

I heard her tell that story to countless women, looking them straight in the eye, underscoring that they too were picking up the torch from generations who came before. She often quoted Congresswoman Lindy Boggs from Louisiana, a mentor of hers, who implored women, “Know thy power!”

To the surprise of no one, Nancy’s workday did not end at 5:00 p.m. She spent every additional waking hour helping her colleagues stay in Congress—flying out to help them in their districts, organizing private lunches for them, and advising them in the way only she could. She was also a prodigious fundraiser, and many aspiring candidates beat a path to her door. Accompanying her to these meetings, I learned lessons about politics that have stayed with me ever since.

One day Nancy and I were at the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee offices, meeting with a young man with stars in his eyes. He settled in across the table from us and launched into his talking points. “I am a really good fit for my district,” he said. “I have the money I need to be competitive, and I think it’s the right next move for me.”

I fought the urge to roll my eyes. Nancy, however, was always gracious and inordinately patient. She listened to his spiel, then asked, “Who is really interested in you being in Congress?”

He looked a bit dumbstruck and stammered, “Well, the business community will support me, and I’m on very good terms with the labor unions.”

“Here’s what I suggest,” Nancy said. “Find one thousand people in your district who care enough about your candidacy that they will write you a check and volunteer, and then come back and see me. If you can do that, I’ll know you can actually win a race.”

I heard that conversation, or a close facsimile, many times. Nancy believed in the importance of grassroots democracy. If you could show her your campaign wasn’t about just you, she would move heaven and earth to help. No matter your gender, race, or ethnicity, she believed what mattered was your commitment and connection to your community. She believed that if you were going to come to Congress, you better be ready to work for the folks back home. Besides which, she knew that this was the only way Congress would ever look like the people of America.

• • •

I had been on Capitol Hill for less than two years when the organizing bug bit once again. By then it was 2004. President Bush was up for reelection. His success was far from settled—between the war in Iraq and the Patriot Act, progressives hoped this would be their chance to make him a one-term president.

A friend from my organizing days, Steve Rosenthal, was the political director for the labor movement, and he was getting ready to run one of the biggest voter outreach efforts in history. But first he did a study: he asked progressive voters in Colorado to keep a stack of all the mail they had received in the last two weeks before Election Day. The results? Voters got dozens of pieces of mail, from many different organizations, all asking them to vote. There was mail from Planned Parenthood, the environmental movement, the AFL-CIO, and of course the candidates and the Democratic Party. It was not only a huge waste of money; it risked turning voters off to the whole process. As Steve said, “Each night, progressive voters came home to a pile of political mailers which they then threw directly in the trash. It’s a disaster!”

Steve and I were talking about what progressives could do to be smarter this time around, when Gina Glantz had an idea. “What if all the major progressive organizations actually talked to each other,” she suggested, “and planned together what they were going to do in elections, instead of all focusing on the same voters?” Gina is the queen of the elegant solution. It made perfect sense, but someone would actually have to do it.

That’s how I found myself starting what became America Votes, the largest collection of progressive grassroots organizations working together to register, educate, and turn out voters. It was a daunting task, but a worthy one. Despite having vowed to never again create something from whole cloth (Never say never!), I realized once more how useless it was to sit around and wait for someone else to build the organization we needed. I took a deep breath and dove back in, telling myself that at least this time I was older and wiser.

I won’t pretend it was all smooth sailing. Putting together that first meeting was a real bear. Carl Pope at the Sierra Club, Andy Stern at SEIU, and Ellen Malcolm at EMILY’s List all thought it was a good idea. Perhaps even more important, so did everyone underneath them, the people who were going to be responsible for voter contact in the election. But coordinating progressive leaders is like keeping puppies in a basket. Just when they are all in, someone jumps out. A male head of a major labor union never got over the fact that he wasn’t in on the original conversation and wound up trying to undermine the plan of bringing all these groups together to collaborate. Just like the song from the musical Hamilton, it seemed like what mattered most to some people was simply being in “The Room Where It Happens.”

The thorniest parts of getting started had nothing to do with the mission or the work. Organizational differences, whether on issues or tactics, got in the way. There were groups that didn’t like the idea of having to share lists or volunteers, or who wanted to be the one to take credit. But gradually, progressive organizations learned that helping each other actually made everyone stronger, even if it meant taking a stand on something that had never been their issue before. In the end we all agreed that it would help everyone if we could determine who was working in Michigan, who was taking on Florida, and how in the world we were going to split up the Philadelphia suburbs. Beating an incumbent president was going to be nearly impossible, and the only way we could succeed was to expand the number of people we were talking to and make the best use of our time and money.

For the very first time organizers sat at the same table and divided up precincts, counties, and phone calls. Even when folks bickered at our headquarters in Washington, in states like Colorado and Pennsylvania and Michigan, working together became second nature. For the people on the ground, it was a dream come true. They knew they had more in common than not, and with limited resources and volunteers, it was a lot smarter to divide up the work. In Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the Planned Parenthood volunteers knocked on doors for the United Steelworkers, who had economic campaign issues that were more salient that year. And in the Philadelphia suburbs, where many pro-choice Republican women would cross over, labor activists distributed Planned Parenthood literature.

The even more exciting result was that for the first time all the progressive leaders got to know each other. It’s still crazy to think that it took organizing America Votes for the heads of the Sierra Club, Planned Parenthood, and the NAACP to get together. What’s more, they all learned the power of grassroots organizing. The president of one national political organization actually knocked on her first door during that election in Ohio. There’s nothing quite like doing the work yourself, talking to voters one on one, to appreciate what is happening in the country.

In starting America Votes, I learned one of the most important lessons of my life: Don’t wait for all the boats to get in the flotilla—just start moving. You may lose a few people, and others may join up along the way, but if you wait until everyone is 100 percent on board, you’ll never get going. At a certain point you have to quit talking about it and start doing it.

There was one really tough setback, of course: We lost the 2004 presidential election by 118,000 votes in Ohio. But the fact that we had built up a national progressive community helped everyone weather the loss. When the blaming began, no one was going to let any single group take the hit. And for every election since then, the major progressive organizations across America have continued to work together.

I meet people all the time who are considering starting their own organizations, whether a student group on a college campus or a national initiative. If you’re thinking of giving it a shot, here are a few of the things I learned so you don’t have to.

First, be practical: Set a goal so you can achieve something concrete. In the beginning it’s going to be the small wins. I knew I could not start the Texas Freedom Network by myself, so my initial goal was to raise enough money in the first three months to pay an assistant and myself.

Second, you have to be willing to ask for money. And believe me, it’s a great skill to have. It tests your proof of concept: if you can find people willing to pitch in $25, then you are onto something. And there aren’t any shortcuts worth taking. How many nonprofit meetings have I been in when someone says, “Maybe we could get Oprah or Matt Damon or Beyoncé to do a fundraiser for us.” That’s just not how it works. Raising money isn’t only about getting an influx of cash; it’s about being able to prove that other people support the idea you’re working on. It’s about building a following.

Third, for better or worse, when you start and run your own organization, you own all the successes and all the failures. Big risk, big gain. It’s like being an entrepreneur, only you’re not trying to make a profit.

Fourth, master the organizing rules of the road: Always have a room that’s half the size you need, with half the chairs you need, so you can guarantee meetings will be standing room only. When you are starting out with new leaders, make sure everyone has the chance to speak. That will be the single best test of whether the meeting went well: Did they get a chance to give their point of view? Besides, you learn more from listening than from speaking. Of course, getting people in a room is 20 percent of the work; the other 80 percent is having something meaningful for them to do after they walk out the door. And no matter what you do, never forget the basics: Provide name tags and food; start on time and end on time; have a next step; have fun. Remember, “If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be part of your revolution.”

There are a ton of great ideas floating around the universe, but the ones that end up becoming reality are those someone commits to doing, no matter what. Why not you?