Introduction

There cannot be many things in man's political history more ancient than the endeavor of governments to direct economic affairs. The need for state action—or the need for state withdrawal from action—has been a constant and fundamental theme of economics in its much shorter history. The endeavors of eighteenth-century England to direct economic policy called forth the splendid scorn of Adam Smith as he wrote the first and greatest masterpiece in economics. His successors continued to cultivate the policy area, and it has been a rare economist of importance whose opinions on economic policy were not well known to his contemporaries.

A persuasive case can be made that our strong interest in economic policy has not been reciprocated by a corresponding interest in economists' views by our society. One may suggest the support for this view by citing the widespread disregard of what is still the widely held preference of economists for free international trade. The customary reasons for the political disregard of professional economic opinion have been that (1) our theories are incomprehensible, and (2) "special interests" triumph in the political process. The former explanation is most unconvincing; our theories are not that difficult, and more difficult theories of physical scientists are accepted with alacrity. The second is a question rather than an answer: which interests control public policy, and why? Doubts such as these gradually grew upon me and created dissatisfaction with the traditional role which we economists have played in the discussion of public policy. These essays reflect the development of my own thoughts on public regulation during the past fifteen years.

Let us consider for a moment the traditional role of the economist in public policy, in which he analyzes, with the aid of economic theory, a specific problem in policy. If he found that a competitive market did not solve the problem efficiently, he recommended that the state take over the solution of the problem —with never a serious question on the comparative efficiencies of

x Introduction

market and government (see chapters 4 and 7). If the competitive market solved the problem well (a quite routine example, not reprinted here, is my article, "The Economics of Minimum Wage Legislation/' the American Economic Review, 1946), the economist suitably lamented the intervention of the state. The idea that minimum wage laws were the expression not of confused benevolence but of the well-informed desires of particular regions and classes of workers was not seriously considered by economists.

Several studies in this volume were stimulated by a desire to pass beyond the formal economic theory to determine more precisely the effects of the policies actually adopted. In the first of these (chap. 5), Claire Friedland and I searched for the effects of regulation of electrical utility rates by state public service commissions, and in the second (chap. 6) the review of new issues by the Securities and Exchange Commission was studied to determine whether purchasers of these new issues were benefited by the SEC reviews. The study of the announced goals of a regulatory policy is useful work, and I am delighted that these essays contributed to the development of the now widespread practice of studying the actual effects of public policies.

Often, but of course by no means always, the public policies seem not to achieve much toward fulfilling their announced goals. We found little effect of public regulation on the level of electrical rates or rates of return on investments in utility stocks, or, in the second study, little benefit to the purchasers of new stock issues from the SEC reviews. Eventually the question insists upon posing itself: in such cases, why is the policy adopted and persisted in?

It seems unfruitful, I am now persuaded, to conclude from the studies of the effects of various policies that those policies which did not achieve their announced goals, or had perverse effects (as with a minimum wage law), are simply mistakes of the society. A policy adopted and followed for a long time, or followed by many different states, could not usefully be described as a mistake: eventually its real effects would become known to interested groups. To say that such policies are mistaken is to say that one cannot explain them. I now think, for example, that large industrial and commercial users of electricity were the chief beneficiaries of the state regulation of electrical rates (and in our essay there is some unintentional evidence supporting this hypothesis).

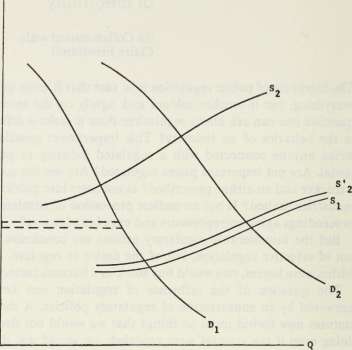

This line of thought leads directly to the view that there is a market for regulatory legislation—a political market, to be sure. Some groups (industries, occupations) stand to gain more than others from boons the state can confer, such as subsidies, control of entry of new firms, and price control—just as some industries gain more than other industries from forming a cartel. Again, some groups are better able than others to mobilize political power, whether through votes or money. Where high benefits join low costs, there we should expect early and strong public regulation. This is the explicit theme of chapter 8—and the implicit theme of chapter 11.

This new focus of economic studies of regulation changes the economists' role from that of reformer to that of student of political economy. The change seems to me eminently desirable. Until we understand why our society adopts its policies, we will be poorly equipped to give useful advice on how to change those policies. Indeed, some changes (such as free trade) presumably are unattainable without a fundamental restructuring of the political system which we are unable to describe. A measure of restraint in our advice on policy would seem to be dictated by a sense of responsibility on the economists' part, and not only by the sense of caution of the body politic to whom we address the advice.

Of course we shall not, and need not, abandon all policy advising until we have unraveled all of the mysteries of the political-regulatory process. The very measurement of the costs and benefits of a policy will influence opinion and policy: one perfectly tenable hypothesis is that a society supports its economists simply because they provide complex kinds of information with speed, elegance, and increasingly more tolerable accuracy. I go beyond this humble but useful role in prescribing how to enforce laws (chap. 10). In any event, the basic assumption of the present approach is not that the traditional theory of economics is unhelpful in studying regulation but, on the contrary, is most helpful when it is applied directly to the understanding of the regulatory process.

I wish to acknowledge two heavy debts. The first is to the remarkable group of colleagues at the University of Chicago who constitute a unique intellectual environment: in addition to that

profoundly wise man to whom this book is dedicated, I must name Gary Becker, Ronald Coase, Harold Demsetz (now of UCLA), Milton Friedman, Reuben Kessel, William Landes, Peter Pashigian, Sam Peltzman, Richard Posner, and Lester Telser. My second debt is to Claire Friedland. She is listed as co-author of one paper (chap. 5), but in fact she is the full and indispensable co-author of every one of the empirical studies (chaps. 6, 8, and 9), and only her different economic philosophy keeps me from blaming her for much of the remainder of the essays.

George J. Stigler

Over Freedom

The Unjoined Debate

The controversy between conservatives and liberals in the United States is so ineffective that it is not serving the purposes of controversy. The quality of controversy is not only low but in fact declining, and what was once a meaningful debate is becoming completely unjoined. An unjoined debate is only an affront to the social intelligence. I intend to blame both parties for this failure, and I seek to contribute to their confrontation on several basic issues. Since I am undoubtedly conservative, and only hopefully fair-minded, you should be warned against that perennial and not always intentional gambit, the restatement of an issue in such a way that it has only one defensible side.

The use of the word extremist to characterize a man and his position on public affairs has become fashionable. A word such as this is used less to describe a position than to dispose of it.

An extreme view is one which is sufficiently different from the accepted view of the majority, or the range of views that encompasses the majority, so that few people hold views still more different. The purpose in labeling an individual an extremist is to put his views outside the range of discussion—they are simply too absurd to merit the attention of normal people. An extremist is an intellectual lunatic—allowed loose if he does not communicate violence, but without an admission ticket to ordinary discourse.

There is merit in excluding the lunatic from discourse. If a man tells me he is Napoleon, or for that matter Josephine, discussion would serve no purpose. If a man asserts that the Supreme Court is filled with loyal but well-disguised communists, I do not wish to spend time on him. Occasionally the lone dissenter with the absurd view will prove to be right—a Galileo with a better scheme of the universe, a Babbage with a workable computer—but if we gave each lunatic a full, meticulous hearing, we should be wasting vast time and effort. So long as we do not suppress the peaceful

Reprinted from the University of Chicago, Chicago Today (Winter 1966).

lunatic, we leave open the possibility that he may convince others that he is right.

If there is one lunatic in a village, there will be a hundred in a city and thousands in a nation. But they will not share the same views: each will be eccentric in his own way. A group of men will share a common outlook only because they share common factual beliefs and accept the same causal relationships. They must have tolerably reasonable logical processes in order to arrive at a common position. The larger the group, the more certain we can be that it is not insane in the sense of being divorced from apparent fact and plausible reasoning.

If a minority group rejects demonstrable truth—as when I do not allow my small child to be vaccinated—the majority may resort to coercion, or otherwise abandon rational discourse. But this is an ultimate sanction, and it is defensible only if two conditions are met: the majority must be absolutely convinced of the correctness of its view; and the mistaken minority must be very small. A decent majority must have a strong sense of self-discipline, and practice a self-denial of power except under the most urgent and unambiguous conditions.

This does not mean that large groups may not be mistaken in their facts or fallacious in their reasoning. Even majorities can be sadly wrong in both respects. The way to deal with error, however, is by the use of careful evidence and straight reasoning. We can be sure that a large group is not misanthropic nor is it mentally incapable of sensible thought, so the bases of rational persuasion are available. The use of force, or even of ridicule, is in general illicit in dealing with groups. The believer in democracy, or even more basically a believer in the dignity of man, has a moral obligation to seek to remove differences of opinion among groups by honest argument.

I do not assert that there must be an element of truth in the position of every minority, and that we ought to sift out this element. There are minority views which I find mistaken—for example, the view that we should have protective tariffs for a large number of industries in the United States. But it is one thing to reject a view, and another to refuse to discuss in detail and in good humor the evidence on which it is held.

The issue of extremism is, so to speak, the extreme form of the problem of the debate between the liberals and the conservatives

The Unjoined Debate 5

of America. Neither side seems to be able to understand the other's position. The greater part of the problem is that neither party seems really to understand the position of the other—to share the same fears, nurture the same hopes, or weigh the same evidence. It is as if there were a dialogue between two men, each of whom spoke the same words but with a different meaning. Let me try my hand as an interpreter. The discourse will be confined to economic issues.

Let us begin with the most fundamental issue posed by the increasing direction of economic life by the state: the preservation of the individual's liberty—liberty of speech, of occupation, of choice of home, of education.

The situation is presently this: everyone agrees that liberty is important and desirable; hardly anyone believes that any basic liberties are seriously infringed today. The conservatives believe that a continuation of the trend toward increasing political control over economic life will inevitably lead to a larger diminution of liberty. The liberals believe that this contingency is remote and avoidable. The more mischievous of the liberals point out that the conservatives have been talking of the planting of the seeds of destruction of liberty for decades—perhaps the seeds are infertile. Liberty is thus not a viable subject of controversy; neither side takes the issue seriously.

The lack of any sense of loss of liberty during the last two generations of rapidly increasing political control over economic life is of course not conclusive proof that we have preserved all our traditional liberty. Man has an astonishing ability to adjust to evil circumstances.

It is not possible for an observant man to deny that the restrictions on the actions of individuals have been increasing with the expansion of public control over our lives. I cannot build a house that displeases the building inspector. I cannot teach in the schools of the fifty states because I lack a license, although I can teach in their universities.

This list of controls over men can be multiplied many-fold, but it will not persuade the liberal that essential freedoms are declining. The liberal will point out that restrictions on one man may mean freedom for another. The building inspector who forces me to build in a certain way is protecting my neighbors from fire and pollution. The law that prevents me from teaching in

a high school on balance keeps incompetents out of the classroom. The restrictions on one man, says the liberal, are a grant of freedom to another man.

Clearly the debate is unjoined—two groups are talking at cross-purposes. There is an issue, and it should be faced: has the past expansion of governmental controls diminished our liberties, and if so, which ones and how much? The burden is squarely on the conservatives. If they say that federal grants to education will lead to federal control of our schools, they ought to give some proof. What has happened in educational areas in which the federal government—or for that matter, the state—has long been acting? They say the farm program takes away a farmer's freedom of choice in occupation, and saps his initiative and independence. After thirty years of this program, some objective evidence ought to be available. The seeds-of-destruction talk is sheer indolence parading as prophecy.

A second striking failure of communication is the problem of individual welfare. The academic conservative is dedicated to an efficient price system. This price system will direct resources to their most important uses, weed out inefficient entrepreneurs, induce improvements in technology, and otherwise contribute to a large national product. Many so-called welfare programs interfere with the workings of this price system and are opposed by the conservative. A minimum wage law is a direct interference with this price system in the market for labor services, and wheat subsidies are a similar interference in the market for foodstuffs—and the conservative says both interferences should be stopped.

To the liberal the conservative's preoccupation with efficiency seems outrageous. The liberal sees a numerous family supported by an ill-paid wage earner, and asserts that an economy as rich as ours can afford to pay a meager $1.25 or $2.00 an hour to this wage-earner. The liberal saw a farm family bankrupted in 1933 by the collapse of our economy, and feels that no legitimate purpose is served by again subjecting farmers to hurricanes of economic adversity. A well-bred liberal will not openly voice his doubts of the benevolence of a conservative, but it is difficult to believe that the liberal does not suspect that the conservative has greater love for profits than for people.

I venture to assert that the conservative is an earnest friend of man but that he looks at welfare in a less personal and restricted

The Unjoined Debate 7

way than the liberal. When the price of wheat is raised by a crop restriction scheme, everyone can observe the benefit to the owner of the farm, and it is this benefit that catches the liberal eye. The conservative is troubled by two other effects of the crop restriction scheme: a tax has been levied on all the consumers of bread; and the restriction scheme almost inevitably will lead to some waste of resources or, differently put, reduce the community's real income. These effects are obviously harmful to non-farmers. The conservative's opposition to minimum wage legislation is more direct: such legislation injures some of the lowest paid workers by forcing them into even lower paid occupations exempt from the act, one of which is unemployment.

The conservative's preference for low prices, strong incentives to diligence and thrift and inventiveness, and similar attributes of efficiency and progress, has indeed a substantial advantage over the liberal's plan of assisting particular needy groups. There are many, many needy groups in a society, and some take a generation or two or even three before they catch the eye of the liberal, be he reformer or politician. The liberal started to care for the poorly housed in American cities a few years ago. In the preceding 300 years the private enterprise economy had sole responsibility for improving their housing. The liberal hopes to take especially good care of the poverty-stricken in Appalachia in 1966—notice the date; but he will ignore the dozens of other groups of equal or greater need until someone publicizes their need. The conservative's programs are designed to help everyone, even groups too poor to have a press agent.

These remarks are intended to illustrate a general proposition: the conservative opposition to intervention by either government or private monopoly is commonly stated in efficiency terms but could always be restated in terms of welfare, and especially in the welfare of consumers. A conservative may be truly humane. It is fair to say that the conservative is compassionate for the great mass of the population which is moderately affected by each public policy, whereas the liberal is compassionate for the special, identifiable group which is most benefited or injured by the policy in question.

Here I am inclined to argue that the liberal should be asked to do more of the work in joining the parties to the debate. If the pebble of public policy sends ripples of harm out over the economy, they

should certainly be reckoned in before deciding whether to cast the pebble. If, to do $50 of good in one place, we must do $30 or $70 of harm elsewhere, we ought at least to know about this harm.

But there is more than this to the conservative position. Suppose we wish to help a particular group of farmers or slum dwellers or a disaster-stricken community. Often it is possible—in fact, usually it is possible—to devise policies which impose a minimum of harm on other groups, or place this harm on a known group capable of bearing it. In our example of the farm program, for example, we can choose between direct income grants that do not lead to a waste of resources or—as at present—a crop restriction scheme that does waste resources. We can finance the benefits to farmers by charging more for bread, or by using general tax revenues. I may add that no economist who is outside active politics will defend the present farm program, whether he be liberal or conservative.

I shall be so absurdly fair-minded as to notice the reply to this discussion by a fair-minded liberal. True, he will say, too little attention has been devoted by us liberals to the effects of our policies on people who cannot afford to send a representative to the congressional committee hearings. We grant you conservatives humanity and shall reckon indirect effects of our policies henceforth. But do you deny that conservatives opposed social security, all farm programs, the urban renewal programs, the recent anti-poverty bill and so forth ... ? Have not the conservatives been too preoccupied with the indirect and diffused costs of programs to give due weight to their direct and immediate benefits for hard-hit groups?

On reflection I am inclined to give two answers. The first is that the rise of per capita incomes (in 1964 prices) from about $500 in 1875 to $2,600 today is a measure of the immense benevolence implicit in a private enterprise system, and this rise has not only done more to eliminate poverty than all governmental policies ever devised, but has in fact also financed these policies. The second answer is, touche.

There are two issues concerning the competence of the state which divide the conservative and the liberal. One is the capacity of the state to withstand special interests; the other is its capacity to get things done. Roughly these issues amount to the questions:

The Unjoined Debate 9

does the state do things it should not, and does it fail to do the things it should?

Everyone will admit that the state enters fields simply because a politically well-situated group wishes assistance. The oil import quota system is attributable to only one argument: there are powerful representatives in Congress from the few states which have oil fields. Our tariff history is the same story many times retold. The continuance of the farm program on its present scale and scope is attributable only to the votes of farm areas. The list of such political ventures can be extended substantially.

The conservative argues that these programs reveal the vulnerability of the political process to exploitation by special groups. The vulnerability is greater, the greater the role of government in economic life: if the oil and textiles industries have been given import quotas, it is hard to deny quotas to meat (1964) and automobiles for Canada (1965). History suggests to the conservative that the way to combat these abuses is to have a self-denying ordinance: Congress must refuse to play the game of helping individual industries or localities.

The liberal's reply is two-fold. His lesser answer is that many of the programs are not so bad as all that: the farm program, for example, has not excluded all poor farmers from its list of beneficiaries. His larger answer is: we cannot refuse to use a weapon of public welfare simply because it is sometimes abused. We cannot abolish hammers because they are also used as blunt instruments.

The failure to join issues becomes obvious if we ask how we are to rid ourselves of policies which informed and disinterested people agree are undesirable policies. The conservative replies that we should make it hard to have any such policy: create (or rather, re-create) a persuasive tradition of nonintervention by Congress in the importation of individual goods, the pricing of particular goods, and so forth. The liberal replies that we must educate the majority of the population up to the level where they understand the objections to the undesirable policies and instruct their representatives to oppose them.

A professor can hardly deny the propriety of using education to achieve enlightened policies. Yet history does not suggest that it is a quick remedy for the abuses of special groups. The level of

formal education of our population has been rising steadily for a century and it has reached historically unprecedented levels. There are probably more years of schooling in our population than world history recorded before 1925. If education of the public leads to lesser perversion of the political process by special groups, we should be able to detect this trend in legislation. The trend is painfully in the other direction: the special interest legislation has been on the rise throughout the twentieth century. The liberals owe it to themselves and to the society to start thinking about effective ways to contain the exercise of the state's economic power.

The second issue is the competence with which the state discharges its economic functions. Does regulation of railway rates keep them at proper levels? Does review of new stock issues protect the investor from loss? Does review of the truthfulness of advertisements protect consumers? Does the federal mediation service reduce the frequency or duration of strikes? Will the review of new drugs save human lives?

I ask you to believe a strange thing. No one knows the answer to questions of this sort. At most only a tiny set of policies have been studied with even moderate care. The conservative has not found it necessary to document his charges of failure, nor the liberal to document his claims of success.

The last subject of unjoined debate which I shall discuss is the question of the competence of the individual. The situation is this: the liberal finds the individual to be steadily losing the capacity to deal with the problems thrown up by an advancing industrial society. The consumer could once look at a horse's teeth, but how does he judge the quality of a motor car? The consumer once bought navy beans by the pound, but how does he know what is in the partially filled box of beans which also contains irium, or is it Pepsodent?

The conservative has several replies. One, which I shall merely note, is that even if liberals do not know how to buy an automobile, conservatives do. A second and more general response is that it is easy to exaggerate the difficulties. Even a non-mechanic can learn by the experience of his friends and of himself whether a given automobile manufacturer habitually makes reliable, durable, comfortable automobiles. And anyway, responsibility is good for a man.

This too is an unjoined issue, one that has a clear analogy to the question of the competence of the state. Take first that manly sentiment: a man should make his own decisions because this improves his character and induces him to enlarge his knowledge. This is both obviously true and plainly false. It does a man's character little good to be sold impure food, or to have his appendix removed by an incompetent doctor, or to be hit by a truck which has no brakes. On the other hand, if a man is allowed to make decisions only when unwise decisions are of no serious consequence, it is indeed hard to believe that experience will be much of a teacher.

The situation is complicated in practice by the differences among men in their ability to cope with given problems. Installment credit, for example, is a boon to the community at large: it permits men to improve the time pattern of their consumption. A few people, however, are hopelessly incompetent to resist the blandishments of salesmen, or even to understand the contracts into which they enter. How many such people must there be before credit sales are regulated to protect them—and, unfortunately, to make life more complex and expensive for the rest of the community?

The larger question of individual competence is really a very different one, however. It is, how well does our economy operate? That this is really the heart of the problem I hope to show by two examples.

The first concerns the sale of food in containers which convey an exaggerated impression of their contents: the partially empty box of a breakfast cereal. Suppose it is true that consumers do not weigh the contents or read the small print which contains this knowledge. There is another source of protection of the consumer: the rivals of the company which engages in this sort of packaging. If consumers buy the half-empty container at the same price as full containers, rivals will begin to lessen the contents and reduce the price—for of course their costs of production have fallen and they are eager to expand sales. This competition will continue until the price per unit of contents is what it was before the idea occurred. If people were as silly as the liberals say, corn flakes boxes would eventually be empty, but they would sell for the price of the cardboard.

In every case of the exploitation of the ignorance of consumers

or workers or investors by a businessman, the leading protector of the exploited class is the businessman's competitors. I need not be well informed, because if anyone seeks to profit by my ignorance, his efforts will merely arouse his rivals to provide the commodity at a competitive price. Competition is the consumer's patron saint.

To be sure, competition does not always exist, and America has an antitrust policy precisely to combat monopolies and conspiracies of nominally independent companies. But the common complaint at the failure of the market to protect consumers and workers and investors is seldom directed to monopoly, but rather to the fact the the forces of competition do not exist, or are too weak, or act too slowly. The liberals have not done a good job of showing the profitability or the prevalence of fraud and deception. They have been content to rely upon scandalous incidents and a priori arguments. The defense of competition by the conservatives has also been too theoretical: the elegant economic theory which describes a competitive system has received entirely too little statistical elaboration.

There is a second resource of a non-expert in a complex world: he can hire an expert. If I want a reliable television set, I can purchase it from a reputable department store, one of whose main services is indeed to find good quality goods as my agent, and to guarantee their quality. If I want my son to get an education, I can hire a college to insure that his instructors are qualified. Our economy is simply plastered with institutions which specialize in providing knowledge, and in some fashion guarantee the accuracy of the knowledge.

The appearance of institutions supplying specialized information does not completely solve the information problem. My teacher, Frank H. Knight, used to say that in order to choose the best physician, a person would have to know how much medicine every physician knew, and if he knew that much, he would have sense enough to treat himself. How do I know that my department store is reliable, that the college will really go out and get good teachers?

I can't be sure of these things, just as I can't be sure a government agency will be staffed by competent men. But time is on my side. These specialized agencies have fairly long lives so I can judge them by results. Marshall Field and my university have been selling appliances and selecting professors for many years,

so I can make a reasonably good prediction of how they will act in the years ahead. The reputation for rendering good service over long periods is the most priceless asset of a knowledge-supplying agency, and I can be sure that even dollar-chasing merchants and dollar-chasing college presidents will struggle hard to preserve this reputation.

These homely examples are not intended to answer the charge that the individual is losing the competence to make his own decisions. They are intended to suggest that a private enterprise economy has the powerful resources of specialization and competition to assist the consumer, the laborer, and the investor. New problems are constantly arising for the individual in modern society. The liberals have no right to assume that the individual is helpless in meeting them; the conservative has no right to assume that the market place will automatically protect the individual.

It is disturbing to look back upon these four grave issues: the preservation of liberty, the humanitarian treatment of the needy; the competence of the state, and the competence of the individual —and in each case observe a failure of the debaters to join issue. It is disturbing because both liberals and conservatives are honest, intelligent, and public-spirited. There are no villains in the picture. It is all the more disturbing that the good humor and good will of the participants to the debate are declining. The intellectual bears a heavy responsibility to restore cogency and mutual respect to the discussion.

The joining of the debate, and the collection and analysis of large amounts of the information I have called for, will not eliminate differences of opinion on public policy. We shall still have men disagreeing on the comparative roles of individual responsibility and social benevolence. No matter how we multiply our researches, there will be unresolved factual and theoretical questions which permit alternative policies to be followed. But an effective joining of the debate should put focus on our controversies and build progress into our policies. We need them.

Reflections on Liberty

For at least the past forty years the conservatives have been in high alarm at the encroachments on liberty by the state. It would be possible to amass a volume of ominous predictions—and not by silly people—on the disappearance of individual freedom and responsibility. Yet if we canvass the population, we shall find few people who feel that their range of actions is seriously curtailed by the state. This is no proof that the liberties of the individual are unimpaired. The most exploited of individuals probably does not feel the least bit exploited. The Negro lawyer who is refused admission to a select club feels outraged whereas his grandfather was probably a complaisant slave. But neither is complacency a proof of growing tyranny. So let us look at what liberties, if any, the typical American has lost in the recent decades of growing political control over our lives. Let us face this American as he completes his education and enters the labor force. Of what has he been deprived?

Some additional barriers have been put in the way of entrance into various occupations. Some barriers consist of the direct prescription of types of training; for example, to teach in a public school one must take certain pedagogical courses. More often, the state imposes tests—as for doctors and lawyers and barbers and taxi drivers—which in turn require certain types of training in order to be passed. But few people consider such restrictions on occupations to be invasions of personal liberty. The restrictions may be unwise—those for school teachers are generally viewed as such by the university world—but since the motive is (we shall assume) the protection of users of the service, and since the requirements are directed to competence even when they are inefficient or inappropriate, no question of liberty seems involved. No one, we will be told, has a right to practice barbering or medicine without obtaining the proper training. The freedom of men to choose among occupations is a freedom contingent on the willingness and ability to acquire the necessary competence.

The mentally and physically untalented man has no inherent right to pilot a commercial plane—or any other type of plane.

For consider: we surely do not say that a man born with weak or clumsy legs has been denied the portion of his liberty consisting of athletic occupations. At most a man is entitled to try to enter those callings which he can discharge at a level of skill which the community establishes. "Which the community establishes": the obverse of the choice of occupations is the choice of consumers. It can be said that the denial of my right to patronize lawyers or doctors with less preparation than the majority of my fellow citizens deem appropriate is the complementary invasion of my liberty. Why should the community establish the lowest levels of skill and training with which I satisfy my needs? The answer is, of course, that on the average, or at least in an appreciable fraction of cases, I am deemed incompetent to perform this task of setting standards of competence. I am, it is said, incapable of distinguishing a good surgeon from a butcher, a good lawyer from a fraud, a competent plumber from a bumbler, and so on.

Now, one could quarrel with both sides of this position: neither has my own incompetence been well demonstrated (especially when account is taken of my ability to buy guarantees of competence) nor has anyone established the ability of other judges to avoid mistakes or at least crudity of judgment. But these are questions of efficiency much more than of justice, so I put them aside not as unimportant but as temporarily irrelevant.

The real point is that the community at large does not think a man should have the right to make large mistakes as a consumer. The man who cannot buy drugs without a prescription does not really rebel at this indubitably expensive requirement. The man who is denied the services of a cheaper and less well-trained doctor or teacher does not feel that he has been seriously imposed upon.

The call to the ramparts of freedom is an unmeaning slogan in this area. If we were to press our typical American of age 22, he would tell us that some infringements on his liberties would be intolerable, but they would be political and social rather than economic: free speech should not be threatened—at least not by the first Senator McCarthy—and minorities should not be discriminated against. No economic regulation of consumers would

elicit serious objection, and this younger person would often be prepared to go even farther in regulating consumers in areas such as health and education. We would have to propose policies remote from current discussion, such as compulsory location of families to hasten racial integration, before we should encounter serious resistance to public controls in principle.

Governmental expenditures have replaced private expenditures to a substantial degree, and this shift poses a related problem of liberty. The problem seems less pressing because private expenditures have increased in absolute amount even though public spending has risen in this century from perhaps 5 to 35 percent of income. Yet the shift has been real: we can no longer determine, as individuals, the research activities or dormitory construction of universities, the directions or amount of medical research, investments abroad, the housing of cities, the operation of employment exchanges, the amount of wheat or tobacco grown, or a hundred other economic activities. But again the typical American finds each of these activities worthwhile— meaning that he thinks that the activity will not be supported on an adequate scale by private persons.

On a closer view of things, some restrictions on individuals as workers will strike most Americans as unfair, especially if they are presented as indictments. Complaints will be aroused by a demonstration that political favorites have been enriched by governmental decisions which excluded honest competitors—and of course this can be demonstrated from time to time, or perhaps more often. The complaint, however, will involve equity much more than liberty.

This conclusion—that Americans do not think that the state presently or in the near future will impair the liberties that a man has a right to possess—is of course inevitable. It is merely another way of saying that our franchise is broad; our representatives will not pass laws to which most of us are opposed, or refuse to pass laws which most of us want. We have the political system we want.

The conservative, or the traditional liberal—or libertarian, or whatever we may call him—will surely concede this proposition in the large. He will say that this is precisely the problem of our times: to educate the typical American to the dangers of gradual loss of liberty. One would think that if liberty is so important that

a statue is erected to her, then the demonstration that a moderate decline of personal freedom leads with high probability to tyranny would be available in paperback at every drugstore. Such a book is not so easy to find. In fact, it may not exist.

No one will dispute that there have been many tyrannies, and indeed it is at least as easy to find them in the twentieth century as in any other. Moreover, the loss of vital liberties does not take place in a single step, so one can truly say that a tyranny is entered by degrees. But one cannot easily reverse this truism and assert that some decrease in liberties will always lead to more, until basic liberties are lost. Alcoholics presumably increased their drinking gradually, but it is not true that everyone who drinks becomes an alcoholic.

An approach to a demonstration that there exists a tendency of state controls to increase beyond the limits consistent with liberty is found in Hayek's Road to Serfdom. But Hayek makes no attempt to prove that such a tendency exists, although there are allegations to this effect. 1 This profound study has two very different purposes: (1) A demonstration that comprehensive political control of economic life will reduce personal liberty (political and intellectual as well as economic) to a pathetic minimum. (I may observe, in passing, that this argument seems to me irresistible, and I know of no serious attempt to refute it. It will be accepted by almost every one who realizes the import of comprehensive controls. 2 ) (2) If the expansion of control of economic life which has been under way in Britain, the United States, and other democratic western countries should continue long enough and far enough, the totalitarian system of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy will eventually be reached. This second theme is not a historical proposition—and no historical evidence was given: it is the analytical proposition that totalitarian systems are an extreme form of, not a different type from, the democratic "welfare'' states to which the book was addressed. Hayek was telling gentlemen drinkers, and especially some Englishmen—who were becoming heavy drinkers—not to become alcoholics.

The thirty-five years that have passed since the outbreak of World War II have seen further expansions of political control over economic life in the United States, and in most western European nations except Germany. Yet no serious diminution of

liberties deemed important by the mass of educated (or uneducated) opinion has taken place. Another hundred years of governmental expansion at the pace of these recent decades would surely destroy our basic liberties, but what evidence is there that such an expansion will continue? Quite clearly, no such evidence has been assembled. But it is one thing to deny that evidence exists for the persistence of present trends to the point where they will endanger our liberties, and quite another to deny that such a momentum exists. Or, differently put, where is the evidence that we won't carry these political controls over economic life to a liberty-destroying stage?

This may be an impeccable debating point, but it will carry much less conviction than an empirical demonstration of the difficulty of stopping a trend. When men have projected the tendency of a society to a distant terminus, they have invariably committed two errors. The tendency develops in a larger number of directions than the prophet has discerned: no tendency is as single-minded as its observer believes it to be. And the tendency encounters in the society other and contradictory forces which eventually give the course of events a wholly different turn. We have no reason to believe that the current prophets are any wiser.

So I conclude: we should fish or cut bait. On the subject of liberty the conservative should either become silent or find something useful to say. I think there is something useful to say, and here is what it is.

The proof that there are dangers to the liberty and dignity of the individual in the present institutions must be that such liberties have already been impaired. If it can be shown that in important areas of economic life substantial and unnecessary invasions of personal freedom are already operative, the case for caution and restraint in invoking new political controls will acquire content and conviction. We cannot scare modern man with incantations, but we can frighten him with evidence. The evidence, I think, will take a variety of forms:

1. A full study of the barriers to entry in occupations, and of the extent to which the barriers can be defended on social grounds, will demonstrate, I believe, that the area of occupational freedom has been seriously restricted simply for reasons of

ignorance or special interest. If this is correct—if the present practices will not bear close review—then the danger of further extensions of such barriers will be substantially reduced.

2. The widespread belief in the incompetence of the individual and the efficacy of economic censorship of tastes is the second large area of potential invasion of personal freedom. This development has surely not benefited from close study: it has happened that errors of judgment or deficiencies of knowledge of a tiny fraction of consumers have led to restraints being imposed on all consumers, without even checking what gains are achieved by the censorship. My own study of the SEC [chap. 6], indeed, reveals a clear instance of where the gains are not worth the cost. If consumers are wiser than the public believes, and if political intervention is not infallible and economical, we shall be better able to stop future invasions of the consumer's freedom.

I do not know whether justice is more or less important than liberty, or whether they are even fully separable. The standards of justice under political direction of economic life, I conjecture, are deplorably low:

3. The state is now the giver of many valuable rights. The favorites get TV channels, or oil import quotas, or FDIC charters, or leases on federal grazing lands, or N.Y. state liquor store licenses, or waivers from the local zoning board. Who has studied the bases on which these favors are allotted? I suspect that a careful study would display vast caprice, much venality, and a considerable number of calluses on applicant's knees and navels. The harshness of competition may mellow somewhat in public repute when alternative systems of distributive justice are studied.

Studies of the types here proposed will, I am reasonably confident, give vitality and content and direction to fears for liberty in our society. But whether the studies confirm the need for reform and vigilance in preserving freedom, or suggest that such fears are premature, they are essential to remove this subject from the category of cliche. It is no service to liberty, or to conservatism, to continue to preach the imminent or eventual disappearance of freedom: let's learn what we're talking about.

TWO The Traditional

Regulatory Approach: The Absence of Evidence

The Tactics of Economic Reform

We are a well-meaning people. We are unanimously in favor of a healthy population, also fully employed, well housed, and deeply educated. To a man we wish prosperous and peaceful nations in the rest of the world, and possibly we are even more anxious that they be prosperous than that they be peaceable. We ooze benevolence, and practice much charity, and could easily become smug in our self-conscious virtue.

The denunciation of American complacency, however, is not my purpose, at least not my explicit purpose. I admire the humane and generous sympathies of our society—sympathies that extend now more than ever before to persons of all colors of skin, to the uneducated and the uncultured and the unenterprising and even the immoral as well as to the educated and the cultured and the enterprising and the moral. We are a people remarkably agreed on our basic goals, and they are goals which are thoroughly admirable even to one, like myself, who thinks one or two less fashionable goals deserve equal popularity.

Fortunately our agreement on basic goals does not preclude disagreement on the way best to approach these goals. If the right economic policies were so obvious as to defy responsible criticism, this would be an intolerably dull world. In fact I believe that each generation has an inescapable obligation to leave difficult problems for the next generation to solve—not only to spare that next generation boredom but also to give it an opportunity for greatness. The legacy of unsolved problems which my generation is bequeathing to the next generation, I may say, seems adequate and even sumptuous.

The Need for Skepticism

It is not wholly correct to say that we are agreed upon what we want but are not agreed upon how to achieve it. When we get to

Reprinted from Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, Selected Papers, no. 13 (1964).

24 Traditional Regulatory Approach: Absence of Evidence

specific goals, we shall find that our agreement does not always extend to orders of importance. For example, some people are willing to preserve personal freedom of choice for consumers even if the choice is exercised very unwisely in some cases, and others will be more concerned with (say) the health of consumers which these unwise choices may impair. Nevertheless, it is roughly true that we know where to go.

We do not know how to get there. This is my fundamental thesis: we do not know how to achieve a given end. We do not know the relationship between the public policies we adopt and the effects these policies were designed to achieve.

This surely sounds absurd: I am saying that although we have had a Securities and Exchange Commission for thirty years, we do not know how to improve the securities markets. I am saying that we have regulated the railroads for seventy-seven years [1964] and do not know how to achieve a sensible railroad rate structure. I am saying that no one knows whether a fair employment practices act will serve to reduce the discrimination against nonwhites in the labor markets. We can get on a bus labelled Economic Reform, but we don't know where it will take us.

You will find it hard to assimilate immediately a challenge to a belief which is so deeply implanted in you that it is simply self-evident. I am reminded of the equally formidable task undertaken in 1819 by a young English clergyman named Richard Whately. In a pamphlet with the title, Historic Doubts Relative to Napoleon Buonaparte, he argued that the evidence that Napoleon had ever existed was very unsatisfactory and inconclusive. He recognized, as I have just done, the difficulty of getting men to rethink an undisputed position.

But is it in fact found that undisputed points are always such as have been the most carefully examined as to the evidence on which they rest? that facts or principles which are taken for granted, without controversy, as the common basis of opposite opinions, are always themselves established on sufficient grounds? On the contrary, is not any such fundamental point, from the very circumstance of its being taken for granted at once, and the attention drawn off to some other question, likely to be admitted on insufficient evidence, and the flaws in that evidence overlooked? Experience will teach us that such instances often occur: witness the

well-known anecdote of the Royal Society; to whom King Charles II proposed as a question, whence it is that a vessel of water receives no addition of weight from a live fish being put into it, though it does, if the fish be dead. Various solutions, of great ingenuity, were proposed, discussed, objected to and defended; nor was it till they had been long bewildered in the enquiry that it occurred to them to try the experiment; by which they at once ascertained, that the phenomenon which they were striving to account for, ... had no existence but in the invention of the witty monarch.

Whately's case against Napoleon's existence rested chiefly upon the utter improbability of the man's career. As just one instance,

Another peculiar circumstance in the history of this extraordinary personage is, that when it is found convenient to represent him as defeated, though he is by no means defeated by halves, but involved in much more sudden and total ruin than the personages of real history usually meet with; yet, if it is thought fit he should be restored, it is done as quickly and completely as if Merlin's rod had been employed. He enters Russia with a prodigious army, which is totally ruined by an unprecedented hard winter; (everything relating to this man is prodigious and unprecedented;) yet in a few months we find him entrusted with another great army in Germany, which is also totally ruined at Leipsic; making, inclusive of the Egyptian, the third great army thus totally lost: yet the French are so good-natured as to furnish him with another, sufficient to make a formidable stand in France; he is however conquered, and presented with the sovereignty of Elba; (surely, by the bye, some more probable way might have been found of disposing of him, till again wanted, than to place him thus on the very verge of his ancient dominions;) thence he returns to France, where he is received with open arms, and enabled to lose a fifth great army at Waterloo; yet so eager were these people to be a sixth time led to destruction, that it was found necessary to confine him in an island some thousand miles off, and to quarter foreign troops upon them, lest they should make an insurrection in his favour! Does any one believe all this, and yet refuse to believe a miracle?

Whately was a young divine when he wrote this piece, which I

26 Traditional Regulatory Approach: Absence of Evidence

interpret to assert that the evidence a typical Englishman possessed for Napoleon's existence was no better than the evidence he possessed for Biblical miracles.

I am jealous of Whately. He was arguing for miracles, which everyone wants to believe in, and in fact everyone wishes to benefit from miracles. Whately soon became an archbishop. I, on the contrary, am compelled to argue against miracles: for I assert that passing a law does not solve a problem. I shall be lucky if I am not fined for loitering on the highway of progress. But on with the task.

I doubt that I can use Whately's approach. One could indeed marvel at the credulity of reformers. In 1887 the railroads of this nation exceeded 180,000 miles, many times the length of the highways of the Roman Empire. The railroad lines and equipment had a value of perhaps 10 billions, or more than twice the expenditures of both sides on the Civil War. The railroads employed 700,000 men—itself the largest industrial army that history had ever seen. This stupendously vast empire was ruled by a set of entrepreneurs of great ability and utter determination. To establish an equitable rate structure, to govern this empire in the most minute detail, the Congress in its wisdom created the Interstate Commerce Commission. A committee of five men, aided by a staff of sixty-one and abetted by an appropriation of $149,000 (as of 1889) was to assume direction of the industry. Could anyone believe that this committee would change much the structure of rates, and not believe in miracles? But since you believe in miracles, I must part company with Whately.

When we undertake a policy reform or improve some part of the economy, there is one way, and only one way, to find out whether we have succeeded—to look and see. Now, only a naive person will believe that historical evidence is unambiguous. Some years ago a young man sued Columbia University, at which I was then professing, for a considerable sum of money because it had failed to teach him wisdom. The fact that he brought the suit was conclusive evidence of Columbia's failure. Nevertheless I agree with this befuddled ex-student that colleges should impart wisdom if they possibly can. I challenge anyone in the whole wide world, however, to prove that, on the average, colleges have taught wisdom, or that, on the average, they haven't. The burden of proof is too heavy for anyone to lift.

Still, it is easy to exaggerate the ambiguity of historical experience: after all, the past is the only source of knowledge of the future. Our trouble, frankly, is less that history speaks obscurely than that we have listened carelessly. We have not studied the experience of economic reform, and know not its successes nor its failures, its lessons on ways to proceed and ways to avoid.

And, of course, the past is instructive only if we study it. Suppose you are ill and I give you a medicine, chosen at random. You will probably survive and, since most medicines are not very potent, even get well. This is not too different from what medical research must be like, for all research involves the liberal use of trial and error. What turns this near-sighted groping into large progress is the recording of the outcome, so that recoveries due only to chance are separated from those due to the beneficial effects of a particular medicine. In a world without memory, there would be, not progress, but an endless succession of random moves, lacking any cumulative improvement.

So the results of experiment should be determined, and compiled. This may be Platitude No. 1 to the scientific investigator, but it is no platitude in the formulation of economic policy In political life it is an idea of considerable novelty, and there are those who would call it un-American except that it is also un-British and un-Russian and un-Indonesian.

Although we have studied the experience under some of our economic policies, the number and importance of those we have not studied are simply astounding. Let me give just three examples that will, I hope, suggest the problem we face in devising good policies for economic reform.

My first example is the regulation of rates for electricity, an area in which modern experimentation began in 1907 in New York and Wisconsin, and for which two-thirds of the states created special public service commissions as long ago as 1915. Yet when, in 1963, Claire Friedland and I began a study of the impact of these regulatory commissions on the level and structure of rates, we were the first investigators ever to do so on even a moderately comprehensive scale [chap. 5].

It was the implicit verdict of the many economists and political scientists who had studied the regulation of electrical rates during the last half century that a study of the effects of regulation was

unnecessary. The bounteous literature implicitly asserts that the influence of the commissions on rates was obvious. The experts knew that of course regulatory bodies are not always competent or honest, but even so the experts were confident that on average the commissions hold down the prices below what the electrical companies would be able to charge because of their monopoly position in each community. If earlier experts could know that a dead fish weighs rather more than a live one, modern experts surely could know that a commission weights down electrical rates. But our study of the effects of regulation on rates came to the conclusion that the effects of regulation are apparently too small to be detected.

You may well find this conclusion incredible. How could hundreds of members of public service commissions have failed to discover long ago the futility of their labors, if they were of negligible import? Why do electrical utilities spend fortunes on lawyers to fight rate cases if they are setting the rates they wish? My ultimate answer is: look at the evidence. My immediate answers are: the efforts displayed by both regulators and industry are no greater than men usually display pour le sport; and if men never persist in what prove to be futile endeavors, why did not the American Indians capitulate by 1700?

A more recent economic reform was the creation of the Securities and Exchange Commission, some thirty years ago, to protect investors from the flamboyant falsehoods that on occasion appeared in the prospectuses that preceded new stock issues. The prospectuses which are now issued after much delay and very substantial expenditures have substituted grim statistics for the enticing loveliness of a seed catalogue. To what end?

Again my main point is that no one had studied the effects of this elaborate machinery on the fortunes of the buyers of new stock issues until I undertook to do so last year [1964, chap. 6]. Neither the security markets nor their regulators nor the academic economists have deemed it necessary to measure the undoubted beneficial effects of three decades of regulation.

Perhaps a word on how one measures the effects of regulation may be useful, for it is no simple task to disentangle one of many influences on the course of events. The SEC study illustrates one approach. Here I hypothetically bought every substantial new issue of industrial common stocks from 1923 to 1927, a period

before the SEC, and from 1948 to 1955. The value of the stock in each of the five years following its issue was also ascertained. We can now calculate what happens to our new investment over time. There remains the problem of allowing for the considerable changes in this world between the reigns of Calvin Coolidge and Dwight Eisenhower. The differential effect of the SEC is measured by comparing values of these new investments with the outcome of buying established securities, over which the SEC has no significant control.

The main finding was that there was no important difference between the 1920s and the 1950s! I may add that it was fortunate that the purchases of new stocks were hypothetical: the investor in new issues of common stock lost twenty per cent of his shirt after two years in both periods.

My last instance is the effect of the Federal Reserve System on the stability of the American economy. This system of central banking was created fifty years ago and has controlled our money system ever since. Here economists have made studies of shorter episodes in the history of the sytem; it is widely accepted, for example, that the restrictive monetary policy of 1931-32 contributed greatly to the financial collapse of 1933. But my colleague, Milton Friedman, collaborating with Anna Schwartz, has recently published the first full-dress study of the effects of the Federal Reserve System upon the stability of prices and banking institutions throughout its history.

By now you may feel able to predict the results: that the Federal Reserve System has had no effect on monetary stability. But no—this time there was an effect:

The stock of money shows larger fluctuations after 1914 than before 1914 and this is true even if the large wartime increases in the stock of money are excluded. The blind, undesigned, and quasi-automatic working of the gold standard turned out to produce a greater measure of predictability and regularity than did deliberate and conscious control exercised within institutional arrangements intended to promote monetary stability (A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, pp. 9-10.)

Many economists, and all bankers, will challenge Friedman's conclusions—in fact a fair number will challenge them even before they learn what he has written. But no one will be able in

30 Traditional Regulatory Approach: Absence of Evidence

good conscience to say that Friedman's study was anticipated or has been contradicted by any other study of comparable scope and thoroughness.

Let me assume, tentatively and hopefully, that you are prepared to acknowledge that the relationship of policies to results is surprisingly obscure. I do not say that our knowledge is nonexistent, because that statement would be distinguishably removed from truth. I do say our knowledge is extremely meager, and I wish now to pass on to you two questions which this deplorable state of affairs poses. First, why are we so poorly informed on the effective weapons of economic reform? Second, how shall we proceed with the reform of our economy?

The reasons we know so little of the effects of past economic policies are worth exploring briefly, because they tell us something about both scholars and political life. The studies that should have been made are the professional responsibility of economists and political scientists. I have no desire to criticize them. Economists are, by their own admission, learned, resourceful, diligent, and benevolent. Political scientists have accused themselves of similar traits. Why have these scholars failed to study much more intensively the relationship between public policies and the course of events? The main answers, I believe, are as follows.

The best scholars are not the best reformers. A scholar ought to be tolerably open-minded, unemotional, and rational. A reformer must promise paradise if his reform is adopted: a candid and qualified estimate of the effects of a given public policy would never arouse a majority from inertia. A reformer should have a low threshold of emotion: I am reminded of Samuel Plimsoll, of the ship line, whose sole stock in trade as a reformer, the London Times reported, was an unrivalled capacity for becoming fervidly indignant upon hearsay evidence. It follows that reformers care little for meticulous scholars—and use only those parts of the scholars' work which fit their needs—very much the way theatrical advertisements present selected adjectives from the reviews. The scholars are normally contemptuous of the reformers, whose scholarly attainments are indeed usually amateur. Reform and research seldom march arm in arm.

The economists have, until recently, been preoccupied with the workings of a comparatively unregulated economic system—what

is loosely described as laissez-faire. They have seldom been in the forefront of economic reform—the two great exceptions being their advocacy of free international trade and policies designed to stabilize aggregate economic activity. They have had a marked preference for free-market organization of economic life.

The reformers, on the contrary, have seldom conceived of any method of achieving a given result except by giving explicit directions to individuals to act in the desired way. When a reform is not achieved by a given regulatory body, the reformers know no other solution than to give this or some other regulatory body more power and more instructions.

Economic reformers, moreover, have had one wondrous advantage for a century or more: the economy was improving in its performance in most ways, so most policies could claim success even if economic progress was quite unrelated to the reform. Some policies were designed to reduce poverty, but the Western economies were all becoming richer and poverty was diminishing as a result of economic growth. Other policies were designed to improve foods and homes, but technology was also striding forward here. Still other policies were designed to improve markets, but the advance of transportation and communication was also improving markets. It is as if the college dining room were to claim sole credit for the fact that seniors weigh more than freshmen.

If close study of the effects of previous reforms had been demanded by our political conscience, it would have been supplied in the past. There is an economic law, named after J. B. Say, to the effect that every offer of goods for sale is an implicit demand for the goods that will be received in exchange. Similarly there is a Say's law of scholarship: professors will study any problem that the society really believes in need of study. Our society has not believed that a close study of the process of economic reform is essential to devise effective reforms.

If I may be permited to insert a refined advertisement, our long-run prospects for rational reform will be much improved as soon as our young people recognize the complexity of the problem. There is an absurd notion abroad that we mostly understand how our economy works and that a democracy—or, for that matter, a dictatorship—knows how to utilize the accumulated knowledge of the social sciences in legislation and

32 Traditional Regulatory Approach: Absence of Evidence

administration. On the contrary, we are far from understanding either our economy or the ways in which to improve it, and the room for creative work in the social sciences is immense. If Mr. Nobel had been a wiser man, he would have directed his prizes to the social sciences to dramatize that really difficult goal of man, the achievement of a civilized society.

The Methods of Effective Reform

Now let me turn to what we should do, pending the vast research we need to inform our actions. We are a reforming society—we have been changing things incessantly since our founding—and we shall not suspend our discontents with economic life for a generation while scholars argue and computers hum. I suggest that we have failed to make anything like adequate use of the most powerful weapon of reform, and my final remarks are devoted to this weapon.

Reformers, I have remarked, are generally rather literal and direct-minded. If they wish to improve housing, they seek to have the state erect houses. If they wish to reduce accidents in factories, they pass a law against unfenced machinery. If they wish to help farmers to have remunerative prices, they pass a law which sets a minimum price. Yet we have seen that such policies are often unsuccessful.

The powerful weapon they overlook is the appeal to the self-interest of individuals. If incentives can be contrived to persuade people to act voluntarily to the goal of reform, we can be confident that our reforms will be crowned with success. Let me spell out and defend this bold claim.

That self-interest is a powerful drive is not really disputable. We recognize its strength so fully that we are not even conscious how much and how confidently we invoke it. Consider a very simple example. A progressive income tax—a tax taking higher percentages of larger incomes—is always reinforced by penalties on rich people who fail to pay their full tax obligations. But the progressivity would also be defeated if the less well-to-do taxpayers paid more than the tax the law demanded. You would think it odd, however, if I proposed that we impose severe penalties on those lower income families which overpaid their tax: quite aside from any other question, I would be assured that overpay-

ment of income taxes was not a widespread problem in America. Or if I proposed a law prohibiting people from breaking into houses to contribute money to the tenants, I would be assured again that there really was no need for such legislation. We really know that self-interest is an extraordinarily powerful drive in man.

It may avoid useless controversy if I say at once two additional things about self-interest. First, it obviously is not the only force in man. Second, self-interest is not confined to a narrow egotism: the scholar who devotes a lifetime to arduous research is moved less by financial gains than by the respect and admiration of his fellow scholars—and if you doubt this, try publishing his work under your name.

Granted that self-interest is a powerful machine—how can we use it for economic reform? The answer is: by arranging that the people who are acting in a given area have incentives to act the way we wish. Let me elaborate this position through two examples.

The first example is the prevention of industrial accidents. If an accident occurs to a given worker, it will be due to one of four causes:

1. The employer has a dangerous place, so even careful workmen will have numerous accidents;

2. The fellow workers of the injured man have been negligent;

3. The injured worker himself has been negligent;

4. Everyone concerned has been careful but misfortune nevertheless occurred.

If we wish to reduce accidents, we may pass laws that machines must be fenced and workers must be careful, subject to penal sanctions. But we also reduce accidents if we put the costs of accidents partly or wholly on the people who prevent them. The employer should bear financial responsibility for the injuries due either to his operating a dangerous place, or to his maintaining an undisciplined shop in which fellow workers are allowed to be negligent. The injured worker should bear the costs of his own negligence.

Several hostile questions are immediately posed by this kind of use of financial incentives. Will not the employer flirt with bankruptcy to save a few dollars of expenses? Most employers dislike a finite chance of bankruptcy but we may require insurance, as indeed we now do with automobiles, which are also

34 Traditional Regulatory Approach: Absence of Evidence

unfenced dangerous machines. Will not the worker ignore the costs to himself of negligence? Of course, especially after he has just mailed off a check for twice what he owes as income taxes. Suppose he is careless and injures himself—are we to allow his children to starve that he may learn a lesson?

This last question is more rhetorical than reasoned: in plain fact most injuries do not have major costs, and no children need be deprived of anything if a typical American worker loses a week's pay. But when major accidents occur, or the family is dreadfully poor, of course it should receive assistance. That a policy cannot work effectively in the extreme 1 percent of cases is no reason to eschew its help in the other 99 percent. Too often the argument is in effect that we should not paint the house because the paint will not protect the wood against artillery fire.

I have not studied the effect of financial responsibility upon accident rates in industry, nor has anyone else, so far as I know. Some partial use of incentives is in fact part of our system of workmen's compensation. I predict that where it has been employed it has been much more effective than direct regulation of safety practices. I predict this because the price system is so effective in directing men's energies in a thousand documented cases. I have, in short, a general theory to guide me in this area—a guide that the traditional reformer lacks.

My second example is racial discrimination in the labor market. I take this example because it is in the forefront of public discussion. It is in some ways a troublesome subject, but most reforms are.

The direct method of reducing discrimination in employment is to insist upon quotas of nonwhite workers, presumably proportional to their numbers. This is a most arbitrary standard: we cannot today staff one-tenth of the positions in theoretical physics, or for that matter in economics, with qualified non-whites. It would be unfair, conversely, to hold them to only 10 percent of the best jobs in professional sports, which pay better than professorships of physics or economics. Moreover, the method of direct legislation—or other forms of direct social pressure—seems very unlikely to achieve important results: it works sporadically in time and capriciously in space.

The basic method of decreasing discrimination in the market is to offer a class of workers at bargain rates. This method has in

fact been operative, and the large secular increase in the earnings of nonwhite relative to white workers has been due to the force of competition. The way we can best reinforce this trend is by increasing the financial incentives to employers to hire nonwhites. We do this, not by increasing their wage rates—the market place will do this—but by increasing their skills. We have a distressingly large number of teenage nonwhites who are not in school or employed. I would favor a two-pronged movement to train them for employment at good wages:

1. A comprehensive program of tuition and support grants for teenagers (of any race) who wish to obtain vocational training in any craft at an accredited school. What we did for veterans after World War II out of gratitude we should do for our nonacademic teenagers out of compassion.

2. The removal of barriers to the employment of unskilled young workers at low wages while they are acquiring training on the job. These barriers include minimum wage rates and apprenticeship restrictions.

These latter proposals will not please some people: a fine thing, they will say, to raise the economic status of the nonwhite youth by lowering his wage rate to a dollar an hour. A fine thing indeed, I reply, to raise it from zero to a dollar.

The reduction of accidents and the elevation of the economic status of the nonwhite are admirable goals, we shall all agree. But there are reforms that some of us will wish and others will oppose.

An instance of a reform with debatable purposes is the maintenance of an import quota system on petroleum to protect the incomes of domestic crude petroleum producers. But let us accept this goal for the sake of argument, or more likely for the sake of election. Then the present system is capricious and arbitrary in high degree. It confers boons on particular importing companies proportional to the quotas assigned to them, and to which they have no claim other than that they used to import petroleum. The extent of these boons, and also of the benefits to domestic oil producers, varies with every change in supply and demand conditions either at home or abroad.

A simple old-fashioned tariff would escape all these objections, and provide a designated amount of benefit to domestic oil producers. The difference between foreign and domestic oil prices will accrue to the treasury instead of the importers, and the

36 Traditional Regulatory Approach: Absence of Evidence

amount of this difference will be explicitly decided upon, not left to the whims of circumstance.

I choose this peculiar area of economic reform to show that the price system can be employed even for reforms of which many non-Texans do not approve. The price system can be used to achieve foolish as well as wise goals.

Effectiveness is a vast claim for the price system, but there may well be ruthless systems of direct control which are also effective. Two quite different considerations lead me to urge the use of the price system wherever possible.