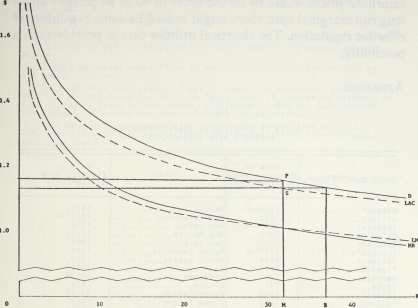

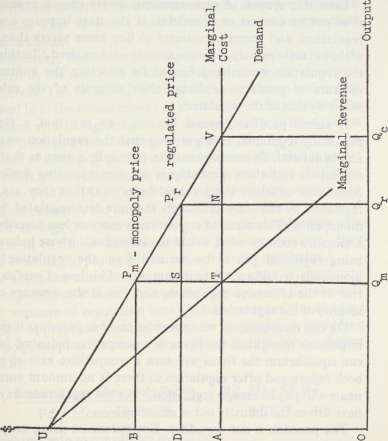

The second circumstance is that the regulatory body is incapable of forcing the utility to operate at a specified combination of output, price, and cost. As we have drawn the curves, there is no market price that represents the announced goal of competitve profits; let us assume that the commission would set a price equal to average cost at some output moderately in excess of output OM, say at R. Since accounting costs are hardly unique, there is a real question whether the regulatory body can even distinguish between costs of MS and MP. Let the commission be given this

What Can Regulators Regulate?: The Case of Electricity 73

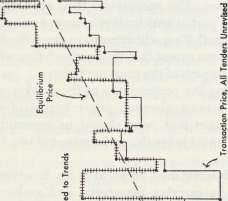

Fig. 2

knowledge; then the utility can reduce costs below MS by reducing one or more dimensions of the services which are really part of its output: peak load capacity, constancy of current, promptness of repairs, speed of installation of service. It can also manipulate its average price by suitable changes in the complex rate structure (also with effects on costs). Finally, recognize that the cost curve falls through time, and recognize also the inevitable time lags of a regulatory process, and the possiblity becomes large that the commission will proudly win each battlefield that its protagonist has abandoned except for a squad of lawyers. Since a regulatory body cannot effectively control the daily detail of business operations, it cannot deal with variables whose effects on profits are of the same order of magnitude as the effects of the variables upon which it does have some influence.

The theory of price regulation must, in fact, be based upon the tacit assumption that in its absence a monopoly has exorbitant power. If it were true that pure monopoly profits in the absence of regulation would be 10 or 20 percent above the competitive rate of

Traditional Regulatory Approach: Some Evidence

return, so prices would be on the order of 40 or 80 percent above long run marginal cost, there might indeed be some possibility of effective regulation. The electrical utilities do not provide such a possibility.

Appendix

TABLE Al

DATES OF CREATION OF STATE COMMISSION ELECTRIC RATE JURISDICTION

Source: State laws, statutes, Public Utility Commission reports; Bonbright and Co. and F.P.C. surveys, and correspondence with commission, unless otherwise noted.

No jurisdiction to change existing contracts.

No jurisdiction over contracts with municipalities.

c Approves changes in rates only (i.e., new rates).

"Concurrent jurisdiction" with municipalities. Commission hears appeal s.

1921 Court decision: no authority in cities controlling public utilities under home-rule amendment of 1912. Denver (a home-rule city) voted to surrender control to commission in early 1950's. Number of home-rule cities in which commission has no jurisdiction is given as 13 in 1954.

Sets maximum rates only.

9 Power to investigate upon complaint only.

_None through 1960.

Authority outside cities, 1954.

J Munici pal i ties fix rates; commission hears appeals only.

Power to fix rates in New Orleans, and other cities voting to surrender control, from 1921 on, subject to optional powers of municipalities. Primary control shifted from municipalities to state commission in 1934.

Source: Barnes, I., "Public Utility Control in Massachusetts," 1930,

What Can Regulators Regulate?: The Case of Electricity 75

p. 96. Requirement to furnish information to Gas and Electric Commission begins 1908.

m None in cities through 1960.

n Most companies are public.

Commission had jurisdiction in cities under 10,000 population from 1921 on.

p Ri gh t to change rates fixed by municipal franchise established by 1915 court decisions.

^Jurisdiction over maximum electric rates, on complaint, granted in 1910, but no rate cases reported. In 1922, power of commission extended to allow fixing of rates on own motion. 1922 report indicates jurisdiction over electric utilities considered "recent" by commission.

r Excludes services rendered to a municipal corporation in 1914. In 1918, power strengthened so that utilities cannot change rates without commi ssion approval .

(Appendix continued on next page)

TABLE A2 AVERAGE REVENUE PER KWH BY STATE, IN CENTS, 1907-37

1922

1927

1932

Mai ne

New Hampshire.

Vermont

Massachusetts . Rhode I si and . . Connecticut. . .

New York

New Jersey.... Pennsyl vani a . .

Ohio

Indi ana

Illinois

Michigan

Wisconsin

Mi nnesota

Iowa

Missouri

North Dakota. . South Dakota . .

Nebraska

Kansas

Vi rgi ni a

West Virginia. North Carolina South Carolina

Georgi a

Florida

Kentucky

Tennessee

Al abama

Mississippi . . .

Arkansas

Louisiana

Okl ahoma

Texas

Montana

Idaho

Wyomi ng

Col orado

New Mexi co . . . .

Arizona

Utah

Nevada

Washi ngton ....

Oregon

Cal i forni a . . . .

2.19 4.17 3.49

3.38 3.18 2.94 2.22 3.67

2.20

4.01 3.61 2.92 4.08

5.84 4.53 4.32 4.82

1 .57 4.85 5.51 2.57 5.66 5.72 9.01 1 .14

1 .06 1 .94 1 .97

2.22 2.71 2.22

2.75 2.86 2.28 1 .89 2.36

2.76 5.23 3.56 6.52 4.03 4.41 1 .77

2.40 2.32 1 .08 .86 1 .45 4.91

3.86 4.37 4.38

.84 1 .22 5.08 2.49 4.93

2.57 2.09 1 .39

1 .51 1 .78 2.21 2.82 2.32 2.64

1 .86 2.50 1 .50

1 .85 2.42 1 .93 1 .46 1 .82

1 .74

72

55

34

.48

1.13

4.54

3.38 .70 .79

3.66

4.01 3.27 3.24 2.94

.74 1 .37 3.32 2.09 4.93 2.65

.98 1 .46

1 .66 2.11 1 .29

1 .62 3.92 1 .89 3.23 2.32 3.25

2.09 3.22 2.15

2.36 3.02 2.24 2.01 2.43

2.85 1 .94 3.10 6.73 5.58 3.59 2.68

3.55 2.04 1 .22 4.66

4.33 5.26 3.39 3.18

.81 .70 4.97 2.85 5.32 2.59 4.41 1.65

1 .41 1 .39 1 .57

2.06 4.39

2.58 4.04 2.40

,60 ,39 ,62 ,40 ,77

14 ,72 ,83

02 ,27

57

27

2.44

1 .30 1 .54 1 .97 5.51

3.20 2.40 1 .66 4.67

3.39 7.15 2.53

1 .51 2.09 2.18

1 .96 3.80

3.05 3.97 2.55

2.73 3.11 2.68 2.67 3.18

3.15 3.79 2.64 6.01 5.65 3.24 3.29

2.65 *

1 .79 1 .65 2.19 4.59

3.12 1 .90 1 .69 3.59

3.22 2.55 3.12 2.82

2.06 4.49 4.10

1 .45 2.10 2.20

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census of Electrical Industries, quinquennial .

i n d i v

are p

b i n a t

Rates

1927

1932

3.68,

Maryl

Combi

cri te

is 1 e

Not pre idual es resented ion had

for com = 3.44 = 1 .94

1912 and , Was nations r i o n but ss than

sente tabl i , the the s b i n a t 1932 1937 3.22, h i n g t of De

are 10 pe

d separat shments .

combi ned ame regul ions empl = 3.54, 1 =1.13; De

1917 = 2 on, D.C., 1 aware wi included r cent (i

ely t

Wher

data

ati on

oyed

937 =

1 awar

.01 ,

and

th ad

becau

n 192

o avo

e dat

were

stat

are a

2.81

Ma

1922

West

join i

se De

7) of

id di sc1o a for two

used pro us in the s follows ; Montana ryland, a = 2.52, 1 Virginia, ng states 1 aware's

the tota

sure of

or more

vided th

year un

Vermo

and Uta

nd Washi

937 = 1.

1927 =

do not

rated ho

1 for ei

information for

adjoining states e states in the com-der consideration, nt and Rhode Island, h, 1927 = 1.08, ngton, D.C. , 1907 ■ 95; Delaware, 2.39, 1932 = 2.35. meet the above rsepower capacity ther combination.

AVERAGE REVENUE PER KWH BY STATE AND TYPE OF CUSTOMER, IN CENTS, 1932 AND 1937

COMMERCIAL AND INDUSTRIAL

1932

1937

1932

1937

Maine

New Hampshi re

Vermont and Rhode Island

Massachusetts

Connecti cut

New York

New Jersey

Pennsylvania

Ohio

Indi ana

II1 inois

Michigan

Wisconsin

Mi nnesota

Iowa

Missouri

North Dakota

South Dakota

Nebraska

Kansas

Delaware, Maryland, and Washington, D.C

Delaware, Maryland, Washington, D.C, and West Virginia

Virginia

West Vi rgi nia

North Carol i na

South Carolina

Georgi a

Florida

Kentucky

Tennessee

Al abama

Mississippi

Arkansas

Louisiana

Oklahoma

Texas

Montana and Utah

Idaho

Wyomi ng

Col orado

New Mexi co

Arizona

Nevada

Washington

Oregon

Cal i form' a

6.2 7.3 5.9

5.4 6.0 5.3 4.4 5.4

5.7 6.6 4.9 7.0 7.1 5.7 5.5

5.0* 5.6

t 5.8 5.6 5.4 6.7

6.2 6.2 5.3 6.6

7.3 7.6 6.3 6.2

4.8* 3.6 6.8 6.1

5.3

5.6

5.8*

5.3

4.6

5.0 5.5 4.6

3.9 4.7 4.3 3.5 3.8

4.1 5.0 3.9 4.7 5.1 4.6 4.9

4.1 4.4 3.8

4.2 3.4

5.7 5.7 5.3 4.8

4.0* 3.1 6.1 5.5

2.7 2.8 3.8

1.4

2.9

2.7*

3.0

2.8

2.2 2.6

2.6 2.8 2.2 5.4 4.9 2.7 2.5

1 .9* 2.0

t 1.4 1.4 1 .8 3.6

2.5 1.4 1 .4 3.0

2.6 1 .9 2.6 2.3

2.3

1 .3 1 .7

1 .5

2.4

2.2*

2.4

2.3

1 .8 2.4 1 .6

6

2.1

1 .8 1 .3 1.4

1.9 1.7

2.2 1 .6 1 .9 1.9

.9* 1.3 3.0 2.5

2.1

1 .2

1 .6 1 .5

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census of Electrical Industries, quinquennial.

Not presented separately to avoid disclosure of information for individual establishments. See table A2, footnote, for criterion for inclusion.

See combined data for Delaware, Maryland, Washington, D.C., and West Virginia.

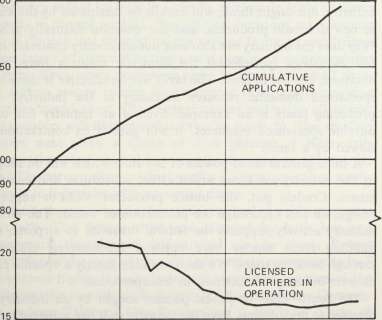

Public Regulation of the Securities Market

It is doubtful whether any other type of public regulation of economic activity has been so widely admired as the regulation of the securities markets by the Securities and Exchange Commission. The purpose of this regulation is to increase the portion of truth in the world and to prevent or punish fraud, and who can defend ignorance or fraud? The Commission has led a scandal-free life as federal regulatory bodies go [1964!]. It has been essentially a "technical" body, and has enjoyed the friendship, or at least avoided the enmity, of both political parties.

The Report of the Special Study of the Securities Markets, which was recently released, is itself symptomatic of the privileged atmosphere within which the SEC dwells. 1 This study investigated the adequacy of the controls over the security markets now exercised by the SEC. The study was well endowed: it was directed by an experienced attorney, Milton H. Cohen; it had a professional staff of more than thirty people; and it operated on a schedule that was leisurely by Washington standards. The study was not an instrument of some self-serving group, nor was it even seriously limited by positions taken by the administration. Such a professional, disinterested appraisal would not even be conceivable for agricultural or merchant marine or petroleum policy, or the other major areas of public regulation. Disinterest, good will, and money had all joined to improve the capital markets of America.

The regulation of the securities markets is therefore an appropriately antiseptic area in which to see how public policy is formed. Here we should be able to observe past policy appraised, and new policy defended, on an intellectually respectable level, if ever it is.

We begin with an examination of certain of the Special Study's policy proposals. Cohen presents a vast number of recommenda-

Reprinted from the Journal of Business of the University of Chicago 37, no. 2 (April 1964).

tions of changes in institutions and practices. Most are minor, and some are even frivolous (market letters should not predict specific price levels of stocks). The content of the proposals, however, is not our present concern; what is our concern is the manner in which the proposals are reached. More specifically: (1) How does the Cohen Report show that an existing practice or institution is defective? (2) How does the Cohen Report show that the changes it recommends (a) will improve the situation, and (b) are better in some sense than alternative proposals? In answering these questions I shall use the discussion of the qualifications of brokers and other personnel in the industry (chap. 2), although the numerous other areas would do quite as well.

The Formulation of Policy

The Cohen Report tells us that there is cause for dissatisfaction with the personnel of the industry: "From the evidence gathered by the study, it appears that the existing controls have proven to be deficient in some important regards. The dishonest broker-dealer, that 'greatest menace to the public,' to use the words of one Commission official, continues to appear with unjustifiable frequency. Also, the inexperienced broker-dealer too often blunders into problems for himself, his customers, and the regulatory agencies ,, (chap. 2, p. 51; my italics). So there are too many thieves and too many incompetents.

How does Cohen prove that there are enough thieves and incompetents to justify more stringent controls? After all, one can always find some dishonest and untutored men in a group of 100,000: not all the angels in heaven have good posture.

The "proof" of the need for further regulatory measures consists basically and almost exclusively of four case studies. These studies briefly describe four new firms with relatively inexperienced salesmen who were caught in falling markets and in three cases became bankrupt or withdrew from the business. No estimates of losses to customers are made. The studies were handpicked to emphasize the shortcomings oinew firms, because this is the place where Cohen wishes to impose new controls. The studies are of course worthless as a proof of the need for new policies: nothing Cohen, the SEC, or the United States govern-

ment can do will make it difficult to find four more cases at any time one looks for them.

Cohen's second, and only other, piece of evidence, is a survey of disciplinary actions against members of the NASD (National Association of Security Dealers) from 1959 through 1961. To quote the report: "The results of this analysis revealed that the association's newest member firms, which are generally controlled by persons having less experience than principals of older firms, were responsible for a heavy preponderance of the offenses drawing the most severe penalties ,, (part 1, p. 66). Cohen's summary of the statistical study, of which this sentence is a fair sample, would not meet academic standards of accuracy. The study reveals that of 1,014 firms founded before 1941, 223 were involved in disciplinary proceedings between 1959 and 1961; of 1,072 firms founded in 1959-60, only 103 were involved in such proceedings. The data are poorly tabulated (dismissals are included, and duplicate charges against one firm are counted as several firms), but however viewed they do not make a case for the need for more regulation, or for more severe screening of new entrants. 2 Yet Cohen believes that the basis has been laid for his main finding:

The large number of new investors and new broker-dealer firms and salesmen attracted to the securities industry in recent years have combined to create a problem of major dimensions....

More than a generation of experience with the Federal securities laws has demonstrated, moreover, that it is impossible to regulate effectively the conduct of those in the securities industry, unless would-be members are adequately screened at the point of entry [part 1, p. 150].

These alleged findings lead to a series of policy proposals, such as the following:

1. All brokers should be compelled to join "self-regulatory" agencies (such as the NASD).

2. No one who has been convicted of embezzlement, fraud, or theft should be allowed in the industry for ten years thereafter.

3. A good character should be required for entrants.

4. Examinations should be required for prospective entrants.

The Report approves strongly of the six-month training period now required of customers' men in firms belonging to the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE).

Cohen believes that the people dealing in securities with the public should have extensive training and screening such as his own profession requires. My lengthy experience with "account executives ,, of major NYSE firms has not uncovered knowledge beyond what would fit comfortably into a six-hour course. It would have been most useful if Cohen had investigated the experience of customers of a randomly chosen set of account men with diverse amounts of training and experience: Have differences in experience or training had any effect on the profits of their customers? But he never even dreamed of the possibility—or perhaps it was of the need—of pretesting his proposals.

The report takes for granted not only the effectiveness but also, what is truly remarkable, the infallibility of the regulating process:

There is no evidence that these practices are typical ... but regardless of their frequency they represent problems too important to be ignored [part 1, p. 268].

The mere fact that there have been any losses at all is sufficient reason to consider whether there are further adjustments that should be made for the protection of investors [part 1, p. 400].

Observe: no matter how infrequent or trivial the damage to investors, the regulatory process must seek to eliminate it (no doubt inexpensively). Surely rhetoric has replaced reason at this point.

As for alternative methods of dealing with the problem of fraud, only one is mentioned: "A number of persons have suggested that a Federal fidelity or surety bond requirement be imposed in addition to or in lieu of a capital requirement. It would seem, however, that such a requirement would present a number of practical difficulties and that more significant protection to the public can be assured through a Federal net capital requirement. No recommendation as to bonding, therefore, will be made at this time" (part 1, p. 92). I must confess to being shocked by this passage. A number of "practical difficulties ,,

exclude the sensible, direct, efficient way to deal with the problem of financial responsibility—difficulties so obvious and conclusive they do not even need to be mentioned.

When one looks at a well-built theater set from the angle at which the audience is to view it, it appears solid and convincing. When one looks from another direction, it is a set of two-dimensional pieces of cardboard and canvas, which could not possibly create an illusion of validity. So it is with the Cohen Report. Once we ask for the evidence for its policy proposals, the immense enterprise becomes a promiscuous collection of conventional beliefs and personal prejudices.

A Test of Previous Regulation

A proposal of public policy, everyone should agree, is open to criticism if it omits a showing that the proposal will serve its announced goal. Yet the proposal may be a desirable and opportune one, and the inadequacies of a proposer are no proof of the undesirability of the proposal. And—to leave the terrain of abstract and unctuous truth—the past work of the SEC and Cohen's schemes for its future may serve fine purposes even though no statistician has measured these probable achievements. Quite so. But then again, perhaps not.

The paramount goal of the regulations in the security markets is to protect the innocent (but avaricious) investor. A partial test of the effects of the SEC on investors' fortunes will help to answer the question of whether testing a policy's effectiveness is an academic scruple or a genuine need. This partial test will serve also to illustrate the kind of study that should have occupied the Special Study.*

The basic test is simplicity itself: how did investors fare before and after the SEC was given control over the registration of new issues? We take all the new issues of industrial stocks with a value exceeding $2.5 million in 1923-27, and exceeding $5 million in 1949-55, and measure the values of these issues (compared to their offering price) in five subsequent years. It is obviously improper to credit or blame the SEC for the absolute differences between the two periods in investors' fortunes, but if we measure stock prices relative to the market average, we shall have elimi-

nated most of the effects of general market conditions. The price ratios (p t /p) for each time span are divided by the ratio of the market average for the same period. Thus if from 1924 to 1926 a common stock rose from $20 to $30, the price ratio is 150 (percent) or an increase of 50 percent but, relative to the market, which rose by 47.0 percent over this two-year period, the new issue rose only 2 percent.

The choice of the time periods over which to judge the performance of the SEC review is intuitive: immediately after a new issue is floated, its price has not changed enough as a rule to reveal the outcome of purchase; long after the flotation the price is dominated by events which took place after the purchase. Clearly this intuitive argument, though plausible, gives no explicit guidance: the right period to study could be six months or six years.

At any date after the individual purchases a new issue, he has three types of information on which to act: (1) the information available through private channels at the time of flotation, which would include information on the industry as well as on the firm; (2) the information provided only because it is demanded by SEC requirements; (3) information which appears subsequent to the flotation. In practice the distinction between types (1) and (2) would often be hard to draw: the SEC supporter will claim all the improvements over time in type (1) information are due to his agency; the more detached scholar will study the improvements in information which came before 1934, and in areas not subject to regulation. If the distinction is feasible, we could make a direct test of the SEC registration procedure by analyzing stock prices to determine the influence of the SEC-dictated information. 4 In fact, unless such tests can be made, there is no objective way of deciding which kinds and amounts of information to require in a registration statement.

To return to our problem of the period of possible effect of the disclosures in the registration statement, I believe that the effective time intervals should be approximately one to two years. Consider the purchase of the stock of a new company: its preflotation history will be brief and meager, and the prospects at flotation time will be completely submerged by the results of the next two years of operation. Or consider an established enter-

Traditional Regulatory Approach: Some Evidence

prise: its preflotation history is lengthy and substantial, so the disclosures in the prospectus must report chiefly very recent changes, which again are confirmed or refuted by the events of the next year or two.

The annual averages of the quotations (relative to market) are given for common stocks in table 1. In both periods it was an unwise man who bought new issues of common stock: he lost about one-tenth of his investment in the first year relative to the market, and another tenth in the years that followed. The data reveal no risk aversion.

TABLE 1

COMMON STOCKS. INDEXES OF NEW STOCK PRICES RELATIVE TO MARKET AVERAGES

(Issue Year

100)

[Source: see appendix to tables at end of this chapter.]

The averages for the two periods reveal no difference in values after one or two years, but a significant difference in the third and fourth, but not fifth, years.

These comparisons suggest that the investors in common stocks in the 1950s did little better than in the 1920s, indeed clearly no better if they held the securities only one or two years. In fact the

differences between the averages in the two periods are not statistically significant in any year. This comparison is incomplete in that dividends are omitted from our reckoning, although this is probably a minor omission and may well work in favor of the 1920s. 5

The variance of the price ratios, however, was much larger in the 1920s than in the later period: in every year the difference between periods was significant at the 1 percent level, and in four years at the 0.1 percent level. This is a most puzzling finding: the simple-minded interpretation is that the SEC has succeeded in eliminating both unusually good and unusually bad new issues! This is difficult to believe as a matter of either intent or accident. A more plausible explanation lies in the fact that many more new companies used the market in the 1920s than in the 1950s—from one viewpoint a major effect of the SEC was to exclude new companies. 6

An interesting characteristic of the security prices is their correlation at various dates. If the correlation between issue price and price t years later rose from the pre- to the post-SEC period, as compared with the correlation between prices at p k and p k+t (a later interval of equal length), one would be inclined to credit the SECs requirements with having improved the structure of issue prices (as judged by subsequent developments). There was in fact such a change in the correlation coefficients, and an improvement in the structure of issue prices may be due to the SEC. 7

The preferred stocks, which were far more numerous than the common stocks in the 1920s, pose a special problem. We use the market average as the base for measuring investor experience in order to minimize the influence of other factors, but no such market average exists for preferred stocks. The existing preferred stock indexes are actually indexes of the yields of preferred stocks, and exclude defaults or failures, so they do not measure the fortunes of investors in preferred stocks.

The price relatives for preferred stocks are compared with both issue price and common-stock indexes in table 2. Neither base is ideal. I have constructed as a, pis aller an index of preferred stocks which combines the above-average price relatives based upon issue price and the Standard and Poor Index in the proportions of inconvertible to convertible issues (roughly, 2 to 1 in the 1920s; 1

iDOOOOOty

MVOr-rs

COKUXNJOUI

D I— CO LT) Lf> CM

■> C\J <JD CM CO LD

vo r--. o co c\j c\j

c\j co <— r*. c

> o <a-cn wc\j cmp

- irnrno en e\j in i—

oo a.

c_> I >—' oo a: UJ Q. CD

<c ^ oc

C_) LU

o >

(TJ -r- i_

<-> r-^ tj > co

lu oo ^i- lo i£> r-. cm c cu-Q

1/3 CM CM CM CM CM I fCXJE

i cr> CJ3 cr> 03 cr> co -t-> zj

oicnor-ogortuiL +->cncr»cr>CT>CTiCT>cric

3 > co

3 -o e

o a: *—. o <£ o i— z: o

00 <c

^ LU O >-

CM CO r— CM

00 r-^ 00 •=!- 1— cm

r-~ <x> co o l

r- CO CM LO LO CM cr>

ir> 1— co co cm vd r^

N(-(»HOy3NOO

CD •<- M- CO ■!- «♦

>"04->0 >"0-MC

IO 1- (O <T3S_fO

<TJ •— S O (T3 -r- J

<-> r^x>>co LU uo-a>c

Luoo^-LOuar^cMccoJD oocj^Oi— cmoo^-lolocco-i

OO CM CM CM CM CM I HI TJ E I ^1" LO LO ID LO LO Lf> I (TJXJE

1 <t> <Ti <t> cr> C3i co -»-> 3 ■i->CT!0'>0">cj">cr>cT*cj >cr>4-> :

0»r— r— <— 1— 1— CM OO 2T t/> 1— 1— 1— 1—1— 1— 1— *3"00 2

Public Regulation of the Securities Market

87

to 2 in the 1950s). On this compromise basis, the average preferred-stock prices do not differ significantly in the two periods, as is shown in table 3. The preferred-stock data deserve less weight than the common-stock data until a suitable preferred-stock index is developed. Meanwhile the best estimate is that the preferred stocks support the same conclusion as the common stocks. *

TABLE 3

WEIGHTED AVERAGE PREFERRED STOCK PRICES RELATIVES (Issue Year = 100)

[Source: see appendix to tables at end of this chapter. ]

These studies suggest that the SEC registration requirements had no important effect on the quality of new securities sold to the public. A fuller statistical study—extending to lower sizes of issues and dividend records—should serve to confirm or qualify this conclusion, but it is improbable that the qualification will be large, simply because the issues here included account for most of the dollar volume of industrial stocks issued in these periods. Our study is not exhaustive in another sense: we could investigate the changing industrial composition of new issues and other possible sources of differences in the market performance of new issues in the two periods.

But these admissions of the possibility of closer analysis can be made after any empirical study. They do not affect our two main conclusions: (1) it is possible to study the effects of public policies, and not merely to assume that they exist and are beneficial, and (2) grave doubts exist whether if account is taken of costs of regulation, 8 the SEC has saved the purchasers of new issues one dollar.

The Criteria of Market Efficiency

So far as the efficiency and growth of the American economy are concerned, efficient capital markets are even more important than the protection of investors—in fact efficient capital markets are the major protection of investors. The Special Study devotes considerable attention to the mechanism of the most important single market, the New York Stock Exchange.

One can ask whether this market is competitively organized: are the prices of brokers' services set by competitive forces? The answer is clearly in the negative and the Cohen Report is properly critical of the structure of commissions of the NYSE, which is highly discriminatory against higher-priced stocks and larger transactions. The Report explicitly refrains from discussing the compulsory minimum rates set by this self-regulating cartel. The reason for silence is obscure: the present scheme of compulsory private price-fixing of brokers' services seems to me wholly objectionable. The replacement of cartel pricing by competition, with review lodged in the Antitrust Division, would confer larger benefits upon investors than the SEC has yet provided.

The mechanism of response to changing conditions is a more subtle matter, dealt with especially in chapter 6 ("Exchange Markets") of the Special Study. The task of providing continuity and orderliness of markets in specific stocks is now performed by the specialists, aided or observed (as the case may be) by the floor traders. How well do they presently perform their tasks?

1. The NYSE uses a "tick test" of the effects of specialists on short-run price fluctuations. If a transaction takes place below the last different price, it is called a minus tick, and if above the last different price, it is a plus tick. Purchases on minus ticks and sales on plus ticks are considered stabilizing, and in three sample weeks, 83.9 percent of specialists' transactions were of this type. The Special Study rejects this test on two grounds:

1. "A tick by itself does not necessarily represent a change in the public's evaluation of the security." Thus, after a transaction at 35, the specialists will often offer 34V2 and ask 35V2, and a transaction at either price is a so-called stabilizing tick. This represents "only a random sequence of buy and sell orders."

2. The specialists' own profit incentive is to buy low and sell high—and presumably (but the Special Study does not say explicitly) no virtue attaches to profitable activity. (Special Study, part 2, pp. 102-3)

The Special Study demands that the test be applied to a longer sequence of transactions; on individual pairs of transactions the test "can be expected to reveal only cases of grossly destabilizing activity" (ibid., p. 104). Specialists engage in only a third of all transactions, but as a rule at least one-third of the ticks in a stock are negative and one-third positive in a day. Hence the specialists could foster market movements while appearing to stabilize them, or so the Report argues. Thus if the specialist sells in the underlined transactions in the following sequence:

35 34 34% 34 34Vi 33 3 / 4 34,

he is stabilizing by the tick test while riding with a market trend. This prescient behavior is not documented, nor is a specific tick test proposed.

2. The preferred test of the specialist's effect is how his inventory of stock varies as the market price fluctuates: "That is, a member trading pattern which tends to produce purchase balances on declining stock days and sales balances on rising stock days would indicate that members exert a stabilizing influence on the stock days in which they traded" (part 2, p. 55). An analysis is made of changes in specialists' stock inventories on four days. In each case inventories moved with the market—that is, they were destabilizing. But if the analysis is performed on stocks classified as rising or falling, balances moved in a stabilizing fashion in seven of the eight cases (part 2, p. 108). But within these eight groups there were a substantial number of cases in which inventories of stocks moved with the market, so specialist performance left something to be desired. Cohen's standards have not flagged: he expects every specialist to do, not his best, but perfectly. 9

The economist will have observed that the Report has no theory of markets from which valid criteria can be deduced by which to judge experience. The tick test and the "offsetting balances" tests are both lacking of any logical basis: these tests assume that smoothness of price movement is the sign of an efficient market, and it is not. Let us sketch the problem of an efficient market.

Traditional Regulatory Approach: Some Evidence

The basic function a market serves is to bring buyers and sellers together. If there were a large number of people who sent their bid and ask prices to a single point (market), we should in effect observe the supply and demand functions of elementary economic theory. The price that cleared this market would be established—it would be a unique price if there were sufficient traders to produce continuity of supply and demand functions— and trading would stop.

This once-for-all, or at most once-per-period, market differs from most real markets in which new potential buyers and sellers are appearing more or less irregularly over time. Existing holders of a stock wish to sell it—at a price—to build a home, marry off a daughter, or buy another security which has (for them) greater promise. Existing holders of cash wish to buy the stock, at a price. Neither group is fully identified until after the event: I would become a bidder for a stock that does not fall within my present investment horizon provided that its price falls for reasons which I believe are mistaken.

So demand and supply are flows, and erratic flows with sequences of bids and asks dependent upon the random circumstances of individual traders. As a first approximation, one would expect the number of holders of a security to be proportional to the total value of the issue. Then the numbers of bids, offers, and transactions would also be proportional to the dollar size of the issue. This is roughly true: the turnover rate of a random sample of one hundred stocks in one month is classified by the total value of the issues, in table 4, and only in very small and very large issues was there considerable departure from proportionality. 10

TABLE 4

TURNOVER RATES OF 100 STOCKS ON THE NEW YORK STOCK EXCHANGE, MARCH 1961

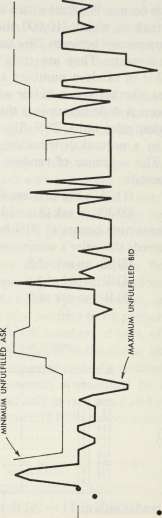

Let us take a very primitive model of a random sequence of bids and asks, and see what this sequence implies for (l)the level of transaction prices, and (2) the time until a bid or ask is met and a transaction occurs. We start with a demand schedule (table 5) for a given stock of which 710,000 shares are outstanding, so the equilibrium price is between 29% and 30. A sequence of bids and asks now appears. They are truly random: two-digit numbers from a table of random numbers are drawn, and the first digit determines whether it is a bid or ask (even or odd, respectively) and the second digit determines the level of the bid or ask (0-9, or, in market price units, 28%-31). (This uniform distribution is replaced by a normal distribution later, but it suffices for the present.) The sequence of random numbers (here called "tenders") proceeds:

(1) 28: a bid (2 is even) of 8 (= 30%),

(2) 30: an ask (3 is odd) of 0 ( = 29%),

Here a transaction occurs at 30% because this highest outstanding bid exceeds the seller's minimum ask. To proceed:

(3)95: an ask of 5,

(4)01: a bid of 1,

(5) 10: an ask of 0.

TABLE 5

DEMAND SCHEDULE FOR A SECURITY

Price

284 (0).

29, (1). 29-4 (2). 29i (3). 294 (4).

30, (5). 304 (6). 304 (7). 304 (8). 31 (9).

ggregate Demand

800,000 780,000 760,000 740,000 720,000 700,000 680,000 660,000 640,000 620,000

This last trader sells at 1 ( = 29) to the fourth tender. The process continues, with the further rule that any unfulfilled bids or asks are cancelled after twenty-five numbers. The transaction price and the minimum unfulfilled asking price and maximum unfulfilled bid are shown in figure 1.

The transaction prices fluctuate substantially, as will be seen— indeed the mean absolute deviation from the equilibrium price

«+_, u

J I I I I l_

I t I I I I I 1 I I

CN CN CN

(taken as the closer of 29% or 30) is $0.34, or 34 percent of the maximum possible absolute deviation. The average delay in fulfilling a bid or ask is 3.8 units (of tenders). 11 These particular results depend upon the special distribution of bids and asks we assume, but any reasonable distribution will generate significant fluctuations in price and significant and erratic delays in filling bids or asks.

The time unit involved in the foregoing analysis is the interval between successive bids or asks. If tenders are proportional to transactions, and the latter to dollar size of issue, this time unit will be inversely proportional to the size of issue. The time unit will be roughly 1/1,000 as long for American Telephone and Telegraph as for Oklahoma Gas and Electric common. In addition the effective price unit for trading may be Va or Vi dollar for the less active stock where it is % for the active stock.

In addition to allowing buyers and sellers to deal with one another, an efficient market is commonly expected to display the property of resilience (to use an unfamiliar word for a property whose absence is called "thinness"). Resilience is the ability to absorb market bid or ask orders (i.e., without a price limit) without an appreciable fluctuation in price. No market can absorb vast orders without large price changes, so this condition must be interpreted as follows: market buy and sell orders of a magnitude consistent with random fluctuation in tenders with an unchanging equilibrium price should not change the transaction prices appreciably.

The reason for making resilience a property of efficient markets may be approached through an analogy. If in a geographical area prices of a product differ, in response to random demand changes, by more than transportation costs, we say that the allocation of the product will be inefficient: A will buy the good for $6 when B is unable to obtain it for $7 (including transportation costs). Alternatively, the owners of the good are not maximizing its value.

Similarly, if random fluctuations in price—under our assumed condition of a stable equilibrium price—lead to price changes greater than inventory carrying costs (the cost of transporting a security from one date to another), the allocation of the product will be inefficient among buyers. Alternatively, the sellers are not maximizing the value of their holdings.

If access to the market is free, speculators will appear to provide resilience by carrying inventories of the stock; they are in fact primarily the specialists of the NYSE plus the floor traders. The speculators will charge the cost of carrying inventories and of their personal services by the bid-ask spread they establish, and in competitive equilibrium this spread will be just remunerative of these trading costs. The technical efficiency with which this inventory management is conducted will be measured by the spread between bid and ask prices.

In addition there are costs of the provision of the machinery of exchange, and these are also part of the cost of transactions. The performance of the main function of the exchange as a market place is subject to economies of scale. The greater the number of transactions in a security concentrated in one exchange, the smaller the discontinuities in trading and the smaller the necessary inventories of securities. As a result the price of a security will almost invariably be "made" in one exchange.

Specialists would then alter the price pattern of figure 1 by setting fixed bid and ask prices (under the present assumption of fixed supply and demand conditions). They will offer to buy all shares at, say, 29% and sell to all buyers at 30, and the difference (the "jobber's turn") will be the compensation for the costs of acting as a specialist. ! 2

To summarize: the efficient market under stationary conditions of supply and demand has the properties:

1. If a bid equals or exceeds the lowest asking price (and similarly for offers), a transaction takes place

2. Higher bids are fulfilled before lower bids, and conversely for offers

3. Prices will fluctuate only within the limits of speculator's costs of providing a market (under competition).

In this regime the cost of transactions (half the bid-ask spread plus commissions) will be the complete inverse measure of the efficiency of the markets. Bid and ask prices will be (almost) constant through time. 13

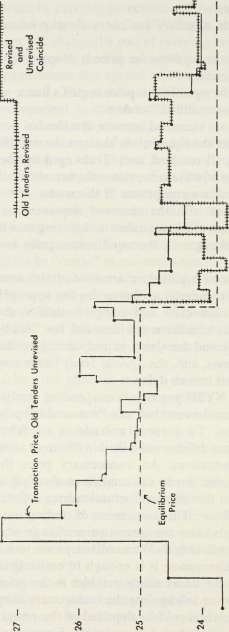

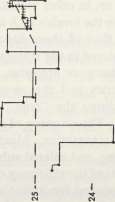

Let us consider now the formidable task of real markets, in which the equilibrium price changes without precise or advance notice. We illustrate the characteristic price patterns in the absence of speculation with figures 2 and 3. The sequences of

bids, asks, and transaction prices follow the procedure of figure 1 with four changes:

1. The random numbers are normally distributed (with = $1.00)

2. In figure 2 the equilibrium price is dropped from $25.00 to $23.75 after 50 tenders

3. In figure 3 the equilibrium price begins a linear upward trend of 5 cents per tender after 25 tenders

4. No tenders are cancelled because of staleness.

In each case, after the equilibrium changes the unfulfilled tenders are alternatively (1) retained, and (2) changed by the amount of the change in the equilibrium price—the two alternatives bracket the most reasonable assumptions. If the reader will compare the equilibrium prices with the observed sequences he will better appreciate the task of the specialist in detecting true changes and avoiding false changes in the equilibrium price (= population value).

If the impacts on equilibrium are sudden and unexpected—as in the examples underlying figure 2—the appropriate market response is an immediate and complete shift to the new price level. Under this condition the demand for "continuity" in a market is a demand for delay in responding to the change in demand conditions, and, the Special Study to the contrary, there simply is no merit in such delay.

The popular NYSE practice of suspending trading until buy and sell orders can be matched at a "reasonable'' price is open to serious objection. To prevent a trade is no function of the exchange, and any defense must lie in a desire to avoid "unnecessary" price fluctuations. An unnecessary price fluctuation is surely one not called for by the conditions of supply and demand of the week even though the fluctuation may reflect supply and demand of the hour. This suspension of trading means that the exchange officials know the correct price change when there is a flood of buy or sell orders. We need not pause to inquire where they get this clairvoyance; it is enough to notice that the correct way to iron out the unnecessary wrinkles in the price chart is to speculate: to buy or sell against the unnecessary movement. The omniscient officials should be deprived of the power to suspend trading but given vast sums to speculate. Since omniscience can

"P 4>

i: > § |.S

- o>

^J

-§

i

-8

-8

■ H i * I 4

; M i n ili hMM ' H 'A I—

-8

•> j\ .iiiiill .\ii|iiiMi|lnr

TXZ1

3^

1

- > "O

0) c Qi 4>

-8

•c

w

S3

surely earn 20 or 50 percent a year on the market, there should be no trouble in raising the capital. To disassociate random from persistent changes is sufficiently difficult, however, to make me very admiring of the courage of those who invest in Omniscience Unlimited.

The wholly unexpected shift in market conditions infrequently occurs—as the assassination of President Kennedy and the heart attack of President Eisenhower illustrate. But almost every event casts a shadow before it: the outbreak of war, the expropriation of foreign subsidiaries, the growth of imports of a product, the glowing income statement—all are more or less predictable as to date and import. The speculators then act within a system in which there is partial anticipation of most events that occur (and many that do not). They will attempt to guess the future course of events, and to the extent that they succeed they will make profits and smooth the path of the price quotations.

In appraising the performance of the market under changing conditions we must abandon our criterion of efficiency in a stationary market that price should be constant over time (p. 000). We now must judge the performance of two functions by the speculator:

1. How efficiently does he perform his function of facilitating transactions by carrying inventories and making bid and ask prices?

2. How efficiently does he predict changes in equilibrium prices, or, in other words, how closely does he keep bid and ask prices to the levels which in retrospect were correct?

The first of these functions is analytically the same as that encountered in the stationary market, but it is now more difficult to discharge or appraise. It is much harder to judge the proper inventories and the proper amount of resources to devote to ascertaining the "true" market price than in the stationary market. The criterion of efficiency is still the cost of consummating a transaction. Much current work on inventory theory, queueing, and related subjects should contribute to the power of our tests of the efficiency of speculators.

The second function, the anticipation of price changes, has one measurable attribute: the trading profits of the speculators are a

measure of their skill in anticipating price movements. What is more interesting is that the positive profits of the speculators also demonstrate that their activity stabilizes prices in the sense of reducing the variance of prices over time. 14

These profits as reported by the Special Study have been quite attractive: on liquid capital of $76.3 million in 1960, specialists made a trading income of $21.2 million (part 2, pp. 371, 373), as well as making $19.6 million in commissions. No profitability data are given for floor traders.

Conclusion

I have argued at suitable length that the Cohen Report makes poor use of either empirical evidence or economic theory, so its criticisms are founded upon prejudice and its reforms are directed by wishfulness. Full disclosure is the rule of the hour, so I must add that the adacemic scholars have not given the capital markets the attention they deserve because of their importance and analytical fascination. The area is replete with problems in the economics of information: what over-the-counter trans-factions should be required to be reported? Should floor traders' orders be delayed in execution to achieve parity with outsiders? and the like. It is an equally attractive area for the theory of decisions under uncertainty: what are the ex post criteria of efficient speculation? The prospectuses of research are glowing—should we start censoring this form of literature too?

Appendix to Tables 1,2, and 3

The lists of new flotation of common and preferred stocks are taken from the Commercial and Financial Chronicle for the earlier period, and Investment Dealer s Digest for the later period. Issues first offered only to stockholders and privately placed issues are excluded, as are public utilities and railroads.

The price quotations are the initial asking price and, at subsequent twelve-month intervals, the averages of the weekly high and low for the week nearest the middle of the month. Averages of monthly highs and lows are employed where weekly quotations are not available. Stock splits and dividends are eliminated, that is, the price of a share is multiplied by the

number of shares the original share has become. If an issue of preferred stock is retired, its retirement value is used in the year of retirement, after which it is dropped from the sample.

The price relatives presented here are relative to issue price.

The market index is Standard and Poors Annual Industrial Index. It is said to be biased upward in the early period but not in the later period; this bias would of course exaggerate the influence of the SEC in our tests. Standard and Poors Index covers only common stocks. Tables 1 and 2 of the text summarize information for these price relatives deflated by the relative value of the market index for the same period.

FOUR Old and New

Economic Theories of Regulation

The Economists' Traditional Theory of the Economic Functions of the State

Economists have long had a deeply schizophrenic view of the state. They study an elaborate and remarkably complex private economy, and find that by precise and elegant criteria of optimal behavior a private enterprise system has certain classes of failures. These failures, of which some are highly complex in nature and all are uncertain in magnitude, are proposed for remedial or surrogate performance by the state.

Simultaneously, the economists—along with the rest of the population—view the democratic state as a well-meaning, clumsy institution all too frequently diverted by emotion and administered by venality. The state is often viewed as the bulwark of "vested interests ,, —and in fact where else can an interest vest? The state is thus at one and the same time the corrector of subtle disharmonies between the marginal social and the marginal private products of resources and the obstinately unlearning patron of indefensible protective import quotas and usury laws.

I propose to reexamine both of these positions, and it comes as no surprise to anyone that an economist seldom reexamines traditional views in order to endorse them strongly. In truth I consider both the complex theory of welfare economics—for that is what we call the economic analysis of market failures—and that blend of hope and cynicism which passes for political wisdom to have been infertile and obfuscatory. Let us, then, reexamine the economic theory of the functions of the state.

By the end of the nineteenth century, economists had developed a sophisticated doctrine of maximum satisfaction which asserted that under competition, and putting aside any quarrels with the distribution of resources among families, competition led to a maximum of satisfaction of the members of an economy. No redistribution of goods among individuals was possible which would benefit even one person without injuring someone else, and similarly the production of any one type of goods could be increased only by decreasing the production of some other type.

If the theorem of maximum satisfaction were literally true, the state would have only two obvious economic functions. The first would be to insure as best it could the condition of competition, for the theorem is easily shown to fail when monopoly is present and powerful. The second would be to alter the distribution of income—at a minimum by caring for persons who owned no income-producing resources, at a maximum by pursuing full egalitarianism. In addition, the state would preserve order and enforce contracts: these tasks devolve on the state primarily because they tend toward monopoly and anyone who controls the army and the courts is the government. But then there would be no need for labor legislation, consumer protection laws, farm programs, or any other of the immense number and variety of economic activities now performed by states.

This smug doctrine could not fail to raise the critical hackles of that race of clever and, by self-admission, humane men who occupy themselves as economic theorists. The search for flaws in the doctrine, or, differently put, for the conditions necessary to make it rigorously true, has attracted the attention of this race for more than a century, and time has not tarnished the medals which are bestowed upon the discoverer of a new exception. Let us review their main accomplishments, which may be subsumed under the three headings of externalities, public goods, and erroneous decisions.

Externalities

An external effect of an economic decision is an effect, whether beneficial or harmful, upon a person who was not a party to the decision. If my neighbor's carelessness in storing gasoline causes my house to burn, and he does not compensate me, this is an externality of his decision. If the parties to a decision do not reckon in the costs which will fall on others, they may undertake activities which are harmful from the viewpoint of society as a whole. If the parties to a decision do not reckon in benefits which accrue to others, they may spurn activities which would be socially advantageous. Private decisions will not lead to a maximum of satisfaction unless externalities are negligible; or, to use essentially equivalent language, resources are not used with maximum

Traditional Theory of Economic Functions of the State 105

efficiency unless all the results, good and bad, of an investment (that is, its marginal social product)accrue to the person making the investment.

The first systematic account of externalities was undertaken in 1912 by Professor A. C. Pigou. The Pigovian analysis has since been refined to levels of purity exceeding those once proclaimed for Ivory soap, but his immensely influential exposition has not been improved upon with respect to the issues I wish to discuss. But first let us briefly review his treatment.

Pigou divided into three classes the individuals who might be affected by an economic decision. The first class was the owners of durable productive instruments such as land. A tenant would not make an improvement which would last beyond his lease because the landlord, not the tenant, would benefit from its usefulness after the lease expired. I shall ignore this class of discrepancies between private (tenant) and social (tenant plus landlord) products after one remark: if you ask why the lease is not written by the transacting parties to overcome this problem, properly compensating the tenant for the improvement, I give two answers. The first is, of course they will, unless it isn't worth the trouble. The second is, Queen Victoria's Parliament was much exercised with this perhaps nonexistent problem for decades and passed laws seeking to ameliorate the tenant's situation.

Pigou's third class of individuals—I postpone for a moment the second class—affected by decisions were other persons in the same industry, fellow producers (or consumers). A simple example will illustrate the problem here. Suppose I import skilled workers and some subsequently leave me to work for a rival, the next time I will not import so many as would be desirable and even profitable if my rival would bear his share of their transportation costs. A more common example arises when my purchases of some input allow the producer to lower its price to my rivals as well as myself—I take no account of the benefit to them. Industries whose costs fall when their output expands are generally too small under competition, and industries whose costs rise with output are sometimes too large (the two kinds of industry are not strictly symmetrical for reasons we need not discuss).

We are left with Pigou's second class—those instances in which

part of the effects of an investment fall on someone other than a landlord or a rival. This is indeed a grab-bag; the following are illustrative Pigovian externalities:

—a monopoly ignores certain burdens it imposes on its customers;

—a lighthouse cannot collect from each ship it guides; —a discoverer of a basic scientific law cannot collect all the benefits it confers;

—the liquor industry does not have to pay for the policemen and prisons its customers employ; —so-called competitive advertising;

—"the crowning illustration'' is the damage done to their children by pregnant women working in factories, a case complicated by Pigou's observation that if they do not work in factories, poverty may do even more damage.

The Pigovian analysis—and here the later literature goes little further—does not really produce a system for discovering where private economic decisions throw important benefits or costs upon persons outside the decision process. Pigou has two important, overlapping classes of externalities for which one could systematically search: monopolies and decreasing cost industries. The remainder come from anywhere and everywhere, and they are more likely to be identified and publicized by a Ralph Nader than by a professional economist.

Neither Pigou, nor his followers for forty-nine years, ever asked a question which in retrospect is obvious enough: why does not the factory owner negotiate with the housewives whose homes are dirtied by the chimney smoke? The mostly implicit answer was that "technically" this negotiation was not feasible, but of course feasibility is a prime subject for economic study, not a prohibition on investigation. In 1961 Ronald Coase published his great article, "The Problem of Social Cost" {Journal of Law and Economics), in which he explained the failure to consult all affected parties to an economic decision by the costs of transactions—the costs of acquiring information, negotiating with parties, and enforcing contracts. Surely this simple reformulation marked a major advance: the economist could systematically study the factors which determined which transactions were feasible and which were not.

Traditional Theory of Economic Functions of the State 107

Coase asserted an almost incredible proposition: if transaction costs were zero, the theorem on maximum satisfaction would always hold, no matter how the rights and duties of parties were assigned by the law. Whether the factory owner or the housewives were responsible for the damage done to laundry by chimney soot, exactly the socially optimum amount of soot would be produced. Whether the automobile driver or the pedestrian was liable for injury to the latter, each would take the socially optimum amount of care to avoid accidents. In this regime of zero transaction costs, no monopoly would restrict output below the optimum level because consumers would pay the monopolist not to do so. Such miraculous corollaries of the Coase theorem have greatly enlivened an early week in courses in economic theory.

Public Goods

A pure public good is defined as any commodity or service which can be used by one person without interfering with the use of the very same service by other persons. The prototype of a public good is national defense: the protection to my neighbor from any known type of attack does not reduce the protection to me. Another example would be a piece of fundamental knowledge: my neighbor's utilization of a mathematical theorem or a new physical principle in no way interferes with my use of them. Although the class of public goods has a long history in economic and political literature, the concept was first formalized in explicit terms by Paul Samuelson as recently as 1954 (The Review of Economics and Statistics).

Even with well-functioning competition, the market cannot supply the proper amounts of a public good. The supply of a public good will usually be monopolistic because it does not cost more to supply 5000 people than to supply 500. Therefore, the known inefficiencies of private monopoly are unavoidable if the public good (whether an air force or a scientific discovery or a fire department) is provided privately.

The monopoly element, however, will often be of negligible importance. For example: only one station can broadcast on a given television channel, and the reception of the broadcast by one household does not interfere with the reception of another household, so it is a public good. With predictable advances in

technology, however, there could be a hundred different television channels in a city, and none would have monopoly power.

There is a second difficulty with public goods. If my neighbors pay for such a good, it will be freely available to me. Hence I have an incentive to understate my desire for the good—for example, to say that the national defense system or the television broadcast is not of the slightest interest to me, or worth at most $1 a year. With everyone similarly motivated to understate his demand price, the good will be supplied in inadequate quantity. Hence the state must undertake the provision of the public good and finance it with a tax.

Again the market failure is not invariable. The television broadcast could be scrambled, and only the viewer with an unscrambling device could view it. Then it would be of no avail to me to pretend that the broadcast was of less value than the fee: the situation would be exactly the same as if I told the automobile dealer that a new car was not worth its full price to me. The dealer would recommend a bicycle; the television station would commend the Carnegie Public Library. The policing of the use of a public good could be so expensive, however, that it was simply out of question, and then the market failure would be complete.

We may note that if the market could exclude any consumer from a public good without cost (so that the TV scrambler was free) and if the demands of consumers could be accurately ascertained (so that the "free rider" could not sponge off of others), the market would supply the optimum amount of public goods as well as private goods.

Erroneous Decisions

Even when all goods are private, and externalities do not exist, there is a third class of market failures. When individuals choose inappropriate means to fulfill their desires, clearly they are not maximizing their satisfactions. There has been no shortage of allegations of such ignorance.

Pigou believed that for articles of wide consumption the price of an article measured well both the desire for the article and the satisfaction obtained from it.

To this general conclusion, however, there is one important exception.

Traditional Theory of Economic Functions of the State 109

This exception has to do with people's attitude toward the future. Generally speaking, everybody prefers present pleasures or satisfactions of given magnitude to future pleasures or satisfactions of equal magnitude, even when the latter are perfectly certain to occur .... This reveals a far-reaching economic disharmony. For it implies people distribute their resources between the present, the near future and the remote future on the basis of a wholly irrational preference. (The Economics of Welfare, 4th ed. [New York, 1932], pp. 24-25)

This one irrationality was serious enough, for it implied that private markets would not conserve resources in proper degree. The list of alleged failures of the market to bring satisfactions commensurate with expectations was already a long one when Pigou wrote. Consider just three examples:

1. Workmen did not properly appraise the risks of injury or death in their employment, and therefore did not receive sufficiently high wages in risky fields. The law of workman's compensation was presumably based on this view of the labor markets.

2. Individuals were incompetent in choosing doctors, lawyers, pharmacists, and so forth, so the state licensed practitioners to insure that they met minimum levels of competence and responsibility.

3. Individuals were incompetent in choosing banks and insurance companies, so these institutions were closely regulated. Even the articles of everyday consumption, in whose purchase Pigou trusted the average consumer, had fallen under food and drug legislation in the United States by 1907.

To extend this list of areas of economic incompetency would be the easiest of sports. Airlines would not choose good pilots, so the FAA licenses them. Investors would buy worthless securities, so the SEC insists upon full disclosure of facts. Households would live in unsafe dwellings if the building code did not protect them. Drivers would pilot needlessly dangerous automobiles if left to their own devices. The very clothing we wear would be flammable and shoddy in the absence of protective federal legislation.

One characteristic of these market failures is that they represent more than imperfect knowledge, since all knowledge is imperfect. The protected individuals would not, of their own volition, acquire a proper amount of information, even though

one can buy information at its cost of production. I could hire a corporation to choose competent doctors (if the American Medical Association would allow it), just as I hire a university to choose competent professors to instruct my children. I could patronize a store which guaranteed its products, and thus delegate to the store the task of testing quality. The irrationality consists of the underinvestment in information.

A second characteristic is that these failures involve nonfulfillment of the individual's own desires, not any censorship of these desires. When the society forbids children to be chimney sweeps or forbids the public sale of heroin, it is not countering market failure but seeking to thwart the market's fulfillment of undesirable desires. We have a good deal of censorship, and, whether it is good or bad, in each case it is a noneconomic source of state activity.

Market Failures as a Basis for Policy

These three types of "market failures" provide the agenda for the state in economic life, according to welfare economics. The externalities, the public goods, and the incompetences of individuals each allow an improvement in economic affairs to be achieved by an intelligent and efficient government. Yet these three classes of actions never developed into even a partial theory of the economic functions of the state. The literature in each area showed an almost perfect immunity to progress in this respect. A useful theory of market failure should tell us in what classes of economic activity the market failures occur. Consider the class of incompetent decisions of consumers. What types of goods and services does the consumer usually purchase mistakenly or inefficiently? Is it new products, or physically dangerous goods, or goods purchased infrequently, or goods purchased in small amounts, or goods whose baneful effects are delayed in time? The answer is, unfortunately, that the economist has no knowledge of when the consumer is incompetent—he accepts the allegations of a Samuel Plimsoll or Upton Sinclair or Stuart Chase or John Galbraith or Ralph Nader, provided they are accepted by the community at large. No economic analysis has been made of the average error in consumer decisions in different types of decisions.

Traditional Theory of Economic Functions of the State 111

Much the same thing can be said about each of the other classes of market failures.

If one wishes to learn what the leading externalities are, he should consult, again, not his economist but his reformer. Any far-flung benefits of education which call for public subsidy were not discovered or measured by economists, and the same can be said of investment in research, the problem of neighborhood deterioration, and the problem of congestion. The one important class of exceptions is the set of externalities which arise from monopoly. Whatever his success, the economist has at least tried to locate probable areas of monopoly and examine the consequences of monopoly. Monopoly aside, however, there is no method in economics of predicting where externalities will arise or whether they will be worth talking about.

Finally, public goods are again a category which is presented to the economist. His achievement has been not to determine whether national defense is a public good, but only to show—in a general way—that private provision of national defense will lead to less defense than the citizens (of this country) desire. This is a thorougly unattractive role which is assigned to the economist: he does not tell the society what to do in the area of economic policy, but merely draws intricate diagrams to explain why the state undertakes what economic functions it happens to undertake. Yet it is his inevitable role so long as he views the economic functions of the state as the performance of those activities which are not performed satisfactorily by the market. How could an economist discover previously neglected externalities? His usual guide is the market, and here by the very nature of the problem the market gives no information: monopoly aside, there are no transactions in externalities; and there are few public goods which are provided privately.

A partial exception to this unwelcome conclusion can be made for consumer incompetence. The market does reveal certain classes of incompetence. The allegation that the labor market is poorly informed and demands public employment exchanges can be tested with data on the dispersion of wage rates. The allegation that a consumer is defrauded in his own eyes can be tested by his subsequent purchases. The allegation that consumers buy too few automobile safety devices can be tested by standard research techniques.

In short, even the most diligent and imaginative economists could play only a limited role in the detection of market failures, and those of us who have fallen short of perfection have been of negligible assistance in this role.

The Competence of the State

Let us start afresh. We have a list, a long list, of market failures. They should be corrected if possible, and there are only two alternatives to the market: the state, and prayer. It turns out that the two were merged in one.

We have remarked on the double view of the state held by economists. The one view is a reading of historical reality— perhaps not a systematic or comprehensive reading, but nevertheless one based on empirical observation. Ask Professors Arrow and Samuelson what they think of the U.S. Post Office. I have not asked, so I must predict the answer: my prediction is that these eminent welfare economists will make comments which fall between indignation and resignation but never approach praise. Furthermore, no respectable welfare or nonwelfare economist will praise the state usury laws which prevent school boards from borrowing money, nor will he praise the achievements of the Interstate Commerce Commission in developing an efficient transportation system in the United States.

We are all acutely aware of the imperfectibility of the political system, of its susceptibility to the well-placed minority, of its tardiness in adopting new technologies, of the bureaus that are forgotten islands of indolence, of the carelessness (or worse) of the public's rights by eminent politicians in advancing their private fortunes. We are all aware, too, that the state has at times been ferociously cruel and vindictive in the treatment of unpopular minorities and causes—we surely need look no farther back than the World War II treatment of the Japanese in California.

The second view of the state is that dictated by the necessities of optimal economic organization: an institution of noble goals and irresistible means. Consider this passage from Oskar Lange:

An economic system based upon private enterprise can take but very imperfect account of the alternatives sacrificed and realized in production. Most important alternatives, like life, security, and health of the workers, are sacrificed with-

Traditional Theory of Economic Functions of the State 113

out being accounted for as a cost of production. A socialist economy would be able to put all the alternatives into its economic accounting. (On the Economic Theory of Socialism, ed. B. E. Lippincott [Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1938], p. 104).

This last sentence would not lose content or meaning if Lange had written: "Almighty Jehovah would be able to put all the alternatives into his economic accounting.'' Or return to Pigou:

It is plain that divergences between private and social net product ... cannot, like divergences due to tenancy laws, be mitigated by a modification of the contractual relation between any two contracting parties, because the divergence arises out of a service or disservice rendered to persons other than the contracting parties. It is, however, possible for the State, if it so chooses, to remove the divergence in any field by "extraordinary encouragements'' or "extraordinary restraints" upon investments in that field. (The Economics of Welfare, 4th ed., p. 192)

Again there would be no loss in content, and perhaps some gain in form, if the last sentence were rewritten: "It is, however, ridiculously simple for his Serene Omnipotence, if it pleases him, to remove the divergence in any field by 'extraordinary encouragements' or 'extraordinary restraints' upon investments in that field."

Neither the cynicism of the first view of the state nor the unreasoning optimism of the second view provides a basis on which the economist can make responsible policy recommendations. We may tell the society to jump out of the market frying pan, but we have no basis for predicting whether it will land in the fire or a luxurious bed.

Economic Regulation

The state—the machinery and power of the state—is a potential resource or threat to every industry in the society. With its power to prohibit or compel, to take or give money, the state can and does selectively help or hurt a vast number of industries. That political juggernaut, the petroleum industry, is an immense consumer of political benefits, and simultaneously the underwriters of marine insurance have their more modest repast. The central tasks of the theory of economic regulation are to explain who will receive the benefits or burdens of regulation, what form regulation will take, and the effects of regulation upon the allocation of resources.

Regulation may be actively sought by an industry, or it may be thrust upon it. A central thesis of this paper is that, as a rule, regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefit. There are regulations whose net effects upon the regulated industry are undeniably onerous; a simple example is the differentially heavy taxation of the industry's product (whiskey, playing cards). These onerous regulations, however, are exceptional and can be explained by the same theory that explains beneficial (we may call it "acquired") regulation.

Two main alternative views of the regulation of industry are widely held. The first is that regulation is instituted primarily for the protection and benefit of the public at large or some large subclass of the public. In this view, the regulations which injure the public—as when the oil import quotas increase the cost of petroleum products to America by $5 billion or more a year—are costs of some social goal (here, national defense) or, occasionally, perversions of the regulatory philosophy. The second view is essentially that the political process defies rational explanation: "politics" is an imponderable, a constantly and unpredictably shifting mixture of forces of the most diverse nature, comprehending acts of great moral virtue (the emancipation of slaves)

Reprinted by permission from the Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science (Spring 1971).

114

and of the most vulgar venality (the congressman feathering his own nest).

Let us consider a problem posed by the oil import quota system: why does not the powerful industry which obtained this expensive program instead choose direct cash subsidies from the public treasury? The "protection of the public" theory of regulation must say that the choice of import quotas is dictated by the concern of the federal government for an adequate domestic supply of petroleum in the event of war—a remark calculated to elicit uproarious laughter at the Petroleum Club. Such laughter aside, if national defense were the goal of the quotas, a tariff would be a more economical instrument of policy: it would retain the profits of exclusion for the treasury. The nonrationalist view would explain the policy by the inability of consumers to measure the cost to them of the import quotas, and hence their willingness to pay $5 billion in higher prices rather than the $3.5 billion in cash that would be equally attractive to the industry. Our profit-maximizing theory says that the explanation lies in a different direction: the present members of the refining industries would have to share a cash subsidy with all new entrants into the refining industry. 1 Only when the elasticity of supply of an industry is small will the industry prefer cash to controls over entry or output.

This question—why does an industry solicit the coercive powers of the state rather than its cash—is offered only to illustrate the approach of the present paper. We assume that political systems are rationally devised and rationally employed, which is to say that they are appropriate instruments for the fulfillment of desires of members of the society. This is not to say that the state will serve any persons's concept of the public interest: indeed the problem of regulation is the problem of discovering when and why an industry (or other group of likeminded people) is able to use the state for its purposes, or is singled out by the state to be used for alien purposes.

What Benefits Can a State Provide to an Industry?