A medium in its infancy, the tablet affords us the opportunity to examine and discover as we create apps. We know users spend considerable time with it and prefer it as an evening companion.

There are several interesting aspects of the few early studies about how people use their tablets and, specifically, how they consume news and information on them.

First, it is an almost universal finding that the tablet is an evening companion. Designer Luke Wroblewski compiled data from several sources that suggest a similar trend: People start using computers and smartphones as they wake up. Usage slightly increases through the workday and slows down as the evening approaches. The tablet, unlike other platforms, sees slower use throughout the day but a higher peak in the mornings and, especially, the evenings as people come back from work. On weekends, tablet usage in the morning and afternoon is slightly higher than the rest of the week, as a Google tablet study found.

According to a Pew Project for Excellence in Journalism study, tablet users seem to be hungry for news. The project notes: “About half (53 percent) get news on their tablet every day, and they read long articles as well as get headlines.” A 2011 BBC/Starcom MediaVest study found that 78 percent of tablet owners surveyed report following both more news stories and a greater range of news topics after acquiring a tablet.

The vast majority of tablet owners—fully 77 percent—use their tablet every day, according to the Pew study. They spend an average of about ninety minutes on tablets.

The Pew study indicates that 40 percent of tablet news users rely primarily on their browser for news. A little less than a third, 31 percent, say they use both their browser and apps equally, while just 21 percent rely mainly on apps. News apps have certainly not become the sole interface for news on tablets.

The BBC/Starcom MediaVest study tells us that tablet users who read news are looking for customized, hands-on ways to engage with the news on tablets. In the study, 85 percent of the users wanted “more tablet-specific content that allows [them] to interact with news stories in a hands-on way.”

A study by Ooyala found that users watched videos 28 percent longer on the tablet than on a desktop computer. Tablet users were also more than twice as likely to watch an entire video than those using a desktop. Videos over ten minutes long took up 42 percent of viewing time on tablets.

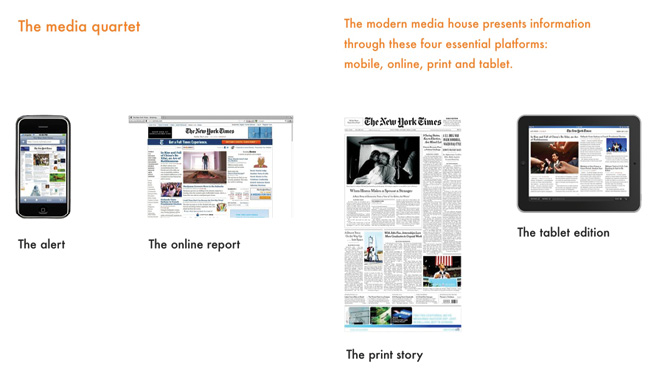

We produce information that is transmitted through a variety of platforms. In a modern media house, we do so through what I call a media quartet: mobile, online, print and tablet. (For more, see the Media Quartet chapter.) I believe this is likely to stay as a feature of how information is presented for at least the next five years. I am sure other platforms will appear, since progress is swift and consumers are eager to test any new product that will allow them to get information more quickly and simply. The task of the modern editor is to realize that each of these platforms has something special to offer. Instead of emphasizing “print first” or “digital first,” as some have proclaimed, an editor should focus on “storytelling first.” This allows each platform to tell the kinds of stories it can do best.

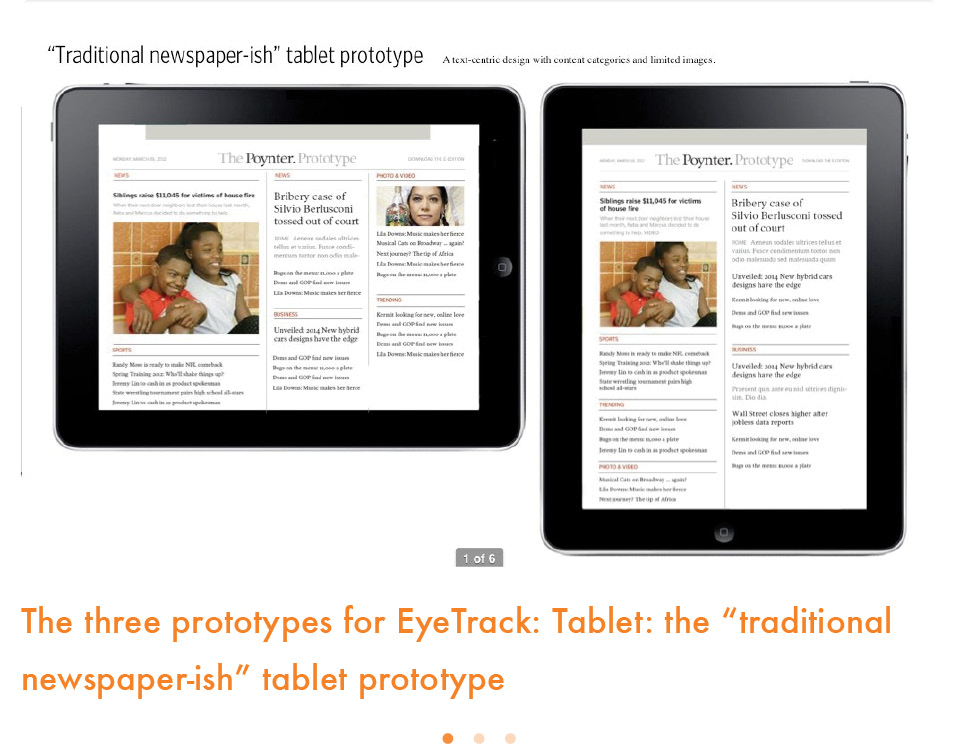

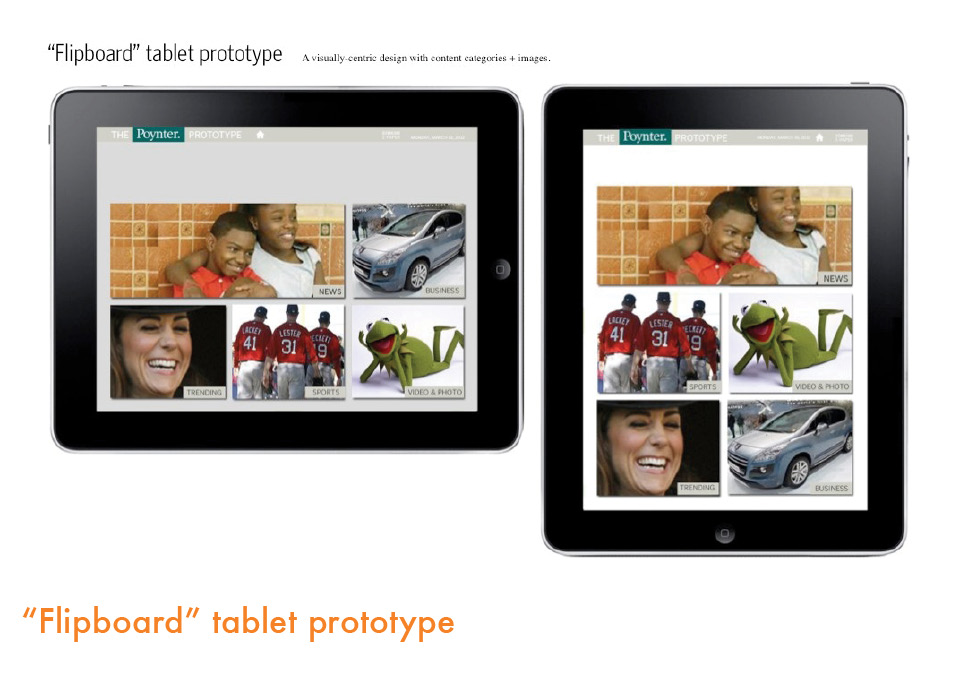

There is probably no research in progress that commands greater curiosity than that of The Poynter Institute for Media Studies’ EyeTrack: Tablet project. I am proud to be part of a talented and inquisitive team at Poynter trying to gather data to help publishers, editors and designers make smarter decisions when it comes to putting their publications into a tablet format.

The Poynter Institute is synonymous with EyeTrack studies. At least two generations of journalists have benefitted from them. At the beginning, we set out to use then-new technology available for eyetracking to find out how the eyes of the reader moved on a newspaper page; then we did similar studies for online reading. Today, with most publishing houses presenting information through the media quartet, EyeTrack moves to the tablet.

In the process, our project team, led by Sara Quinn of Poynter’s Visual Journalism faculty, with David Stanton (Smart Media Creative) and Jeremy Gilbert (Northwestern University, Medill School of Journalism), has decided that we live in a fast-paced world, and, rather than wait to gather all of the data, Poynter will be presenting the findings of the study as it takes place. We have created a test prototype that presents the questions that we designers actively engaged in the creation of news apps consider to be key to their further successful development.

Undoubtedly, navigation is the one most important feature when creating a news app. We must be quick and clear in how we get the user from here to there. Remember, there are often no page (or screen) numbers in these news apps. Users move from section to section on a whim. To me, getting some scientific data on the preferred orientation for tablet users is key, and this is likely to be EyeTrack: Tablet’s greatest contribution.

What have we found out so far? Swiping is preferred to scrolling. iPad users have an overwhelming instinct to swipe horizontally through a full screen photo gallery, regardless of portrait or landscape orientation. I am not surprised here at all, and neither is our Poynter research team. In focus groups, I have personally observed that swiping is more intuitive than scrolling. Early indicators, observed with about a hundred people in an initial sample of the study at multiple sites around the United States, tell us it is so. Participants who were given an iPad in landscape orientation swiped horizontally 93 percent of the time. In portrait, they swiped horizontally 82 percent of the time. This is statistically significant evidence for a horizontal inclination, underscoring that the swipe direction isn’t just a random behavior.

If, as we believe, the best iPad experiences give users total control, swiping comes more naturally and should be championed. In fact, many of us are currently experimenting with “swiping only” news apps, where scrolling is rarely required. Ultimately, the choice of swiping vs. scrolling lies in the hands of designers who make such decisions on the basis of what works best for their publications. We eagerly await the more conclusive results of the Poynter EyeTrack study as we continue to face the excitement and the challenges of translating print publications to the tablet. (See more on swiping vs. scrolling in the Navigation chapter.)

Craig Will, a cognitive scientist designing tablet apps, has proposed a more nuanced description of how we interact with different devices. In his blog post “Engagement Styles: Beyond ‘Lean Forward’ and ‘Lean Back,’” Will proposes a scale of “activity” and “absorption” to describe the differences between various activities. Moreover, he argues that devices may be used for different engagement styles depending, among other factors, on the user’s task, setting and long-standing habits. I have asked him some questions about the tablet in particular:

MARIO: In terms of consuming news on the tablet, most studies indicate it is during the prime evening hours, between 7 and 11 p.m., in what we refer to as “lean-back” mode. We also understand that many tablet users who are engaged in news reading in the evening do so with their televisions on. Do you see these two activities as totally “lean-back,” and, if so, how much concentration is the tablet user applying to the consumption of news and features?

CRAIG WILL: We don’t know enough about how people use the tablet to know what people might be doing differently in the evening hours. The data suggesting high use in the evening that I have seen comes from websites that track usage by different platforms at different hours. This tracks only people using the web browser and is presumably “lean forward” or “high activity’ engagement. Some people have concluded that because people are typically relaxed in the evening, and that tablet use is high in the evening, the tablet must be a “lean back” platform. That doesn’t follow, given where the data comes from. (But I think there must be a lot of high-absorption activity with tablets in the evening.)

I don’t think there is a single type of “news reading.” If people are watching television and using a tablet, I would expect them to be looking at headlines and reading a few paragraphs. But if they are reading a long-form journalism story, I’d expect them to turn off the television (actually or mentally).

In terms of “engagement style,” does the tablet as we know it today offer the most appropriate style for deep reading? We know that long narratives do well on the tablet, and we will continue to analyze that in our upcoming EyeTrack study. We also begin to see the role of websites changing. Since, as many publishers have discovered, online editions are read in the middle of the work day, what users seek are updates more than extended, in-depth coverage or videos, which are more likely to be explored in the more lean-back mode of the tablet.

Is the tablet good for deep reading? There are surely large differences among different people. Some will have no problem focusing for long periods of time. Others may become distracted and browse the web or play a computer game, just a tap away. But, on the average, the tablet may not be as good for deep reading as a dedicated e-reader or printed book. Before there were iPhones and iPads, Donald Norman wrote extensively about “information appliances,” suggesting that these single-purpose devices would replace the PC. (He compared the PC to a Swiss Army Knife, which he might take camping but wouldn’t use in his kitchen.) The success of the iPhone or iPad suggests that he was wrong. But in the long term he could still be right. In a decade tablets will be very cheap, and you may have a blue one you use for deep reading and a red one you use for checking the latest news. You might keep them in different rooms. The primary value of the deep-reading red tablet is that it enforces attentional discipline.

Finally, you have not mentioned much about mobile telephones. Is the activity there totally lean-forward? What type of engagement style do users employ?

What’s a mobile phone? The iPhone is viewed as a phone, but it really is not a phone. It’s a powerful handheld, portable computer that also has a phone capability. The Apple Human Interface Guidelines say that the iPhone will be used by people in an environment in which they are very likely to be distracted, and thus the apps should be very simple and designed to require minimal attention from users. However, people also use their iPhone to read books in bed. What will people do with the old iPhones when they upgrade to a new device and the old iPhone doesn’t make phone calls anymore? Maybe they’ll read books with them. Phones are more likely to be used in the “lean forward” mode, but they won’t necessarily be.