Son, Spirit, Snake

The First Day

No one came to his brother’s funeral. Not even the spirits. Étienne knew it was his fault.

He knelt at the roots of the Moabi tree at the center of Deng Deng village. Its trunk, gray and bone smooth, loomed upward until it fractured into a labyrinth of branches. Leaves like fingers squeezed out the twilight. Next to him, his mother, Thérèse—head bowed, eyes half closed—rocked on her knees while she sang a soft prayer.

“Ancestors, guide my son. Keep my child, Beloved Ones.”

The swish of her cotton dress served as her sole instrument. A bird—or maybe a cat in heat—shrieked among the ebony trees crowding the clearing. Étienne glanced up. Where the pulsating glows of spirits should have filled the forest, there were only shadows. Clay mud houses nearby remained shuttered, though odors of stewed yams and roasting fish escaped from the gaps in their windows and doors. Why didn’t his aunts, his uncles, his cousins come out to sing with them?

And wasn’t it wrong to go this far without spirits or kin present? They might as well be doing witchcraft, for how alone they were.

Étienne shifted his weight so the hem of his scarlet mourning kilt bit less into his knees. Every funeral required at least half a dozen spirits, their presence bathing the Moabi in a frenetic rainbow. But not even Mōndèlé, the White Woman, the spirit of oaths and patron of Snake Clan, had come to dance the sorrow songs. And she always came for his family’s dead.

When a night fever took Étienne’s twin cousins Gisele and Geraldine, when Great-Grandmother Ngo died asleep in her bed, after a cave-in killed his father five years ago, when Étienne was only seven, White Woman had come with spitting cobras and pythons wrapped around her shoulders like a shawl. She’d danced as she wailed with her ten mouths and wept with her robin’s egg eyes.

So where was she now?

Étienne’s eyes slid to the gold bracelet on his wrist. The scales of a geometric snake incised on its curves glimmered up at him.

Grease swam in his stomach. White Woman hadn’t come because of it.

Because of what he’d asked of his brother.

“Remember what he left behind, and all he could have had.”

Still singing, his mother reached into a basket at her side and produced a mottled-brown cane rat. Sensing its fate, it squeaked and tugged at the twine binding its paws.

“Taste this, Ancestors, so the blood of my blood will not be forgotten.”

Thérèse lifted the rat and swung it at the tree’s roots. Once. Twice. The rodent’s spine shattered with a pop. Once more she lifted it, high above her head, then hurled it down. Its skull crunched, then the creature went still.

His mother laid the creature at the base of the Moabi. Drops of ruby blood oozed from its ruined snout. They dripped down the bark to darken the already red soil, and a coppery tang filled the air.

From the basket, Thérèse extracted a small leather pouch. Standing, Étienne took it and dusted off his kilt. The velvet fabric was digging into his skin, and he wished he hadn’t wrapped it so tight around his waist.

He paused as leaves rustled at the far side of the tree. Étienne leaned to peer around its trunk. Instead of White Woman’s silver glow, a python. Its greenish-brown scales blurred together as it slithered between tree roots. It stopped a meter away, flashing a violet tongue at the rat carcass.

His mother nodded to it. “Welcome, honored brother.”

The image of a leathery egg flashed through Étienne’s mind. Its shell split, spilling two snakelets. Slimy with amniotic fluid, they wriggled over each other as they intertwined. A sensation of familiarity swept through him.

The standard greeting. Sibling.

Étienne grimaced. He never liked the way snakes’ voiceless thoughts penetrated his head. The images were simple, mostly what they saw or wanted to eat. But he avoided the creatures when he could. Not for fear of their venom or fangs; as a son of Snake Clan they would do him no harm. It was the way they stared with lidless eyes, their never-still tongues, how they lurked, coiled, in branches. With their picture chatter, he always knew what they saw, even if he didn’t know precisely where they were.

Besides, seeing through a snake’s eyes was … He pitied the rat.

Étienne tried to ignore the python as he opened the pouch and held it over the Moabi’s roots. A moment passed. Another.

He glanced at his mother. She stared ahead, her wide, dark eyes flat and vacant. A week ago, Étienne would have said she had a moon-shaped face, the kind that always seemed to be just about to smile. Now it was hollow and thin, like she was sucking an orange made bitter from being plucked too soon from its tree. Only the skin sagging at the corners of her mouth, the loose braids she hadn’t bothered to retie, betrayed any emotion. What was it? Anger? Grief? Disappointment?

He wished he could sense her thoughts instead of the snake’s.

“Well?” His mother waved a hand for him to continue. “Take this gold …”

Étienne swallowed. He summoned the words she had thrown at him as she tried to explain the funeral rites. Taking in a breath, he hoped he had the right line.

“Take this gold, Tree Between Worlds, and … and?”

“Honestly, Étienne.” She puckered her lips.

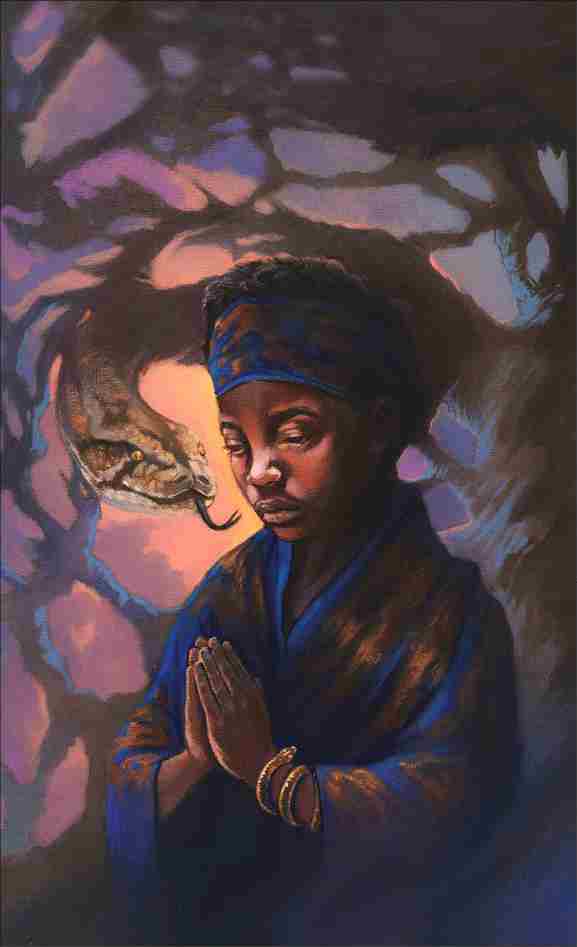

Illustration by Pedro N.

Long Description

“I’m trying.” Étienne winced at the whine in his voice. He’d hoped that his mother would have forgiven him by now. But here he was, ruining Dieudonné’s funeral.

A funeral that wouldn’t have happened if it wasn’t for him.

“Don’t bother singing. Just say it. ‘Take this gold and rejoice.’ Again.”

He gritted his teeth. “Take this gold, Tree Between Worlds, and rejoice in the company of my brother.”

Mumbled, rushed, but at least it came out in the right order.

Étienne tipped the pouch. Gold dust streamed down, winking in the day’s last glow until the metal flakes landed on the rat’s blood. They stuck there, trapped, like stars on a crimson sky.

The Moabi’s branches sighed.

The pouch didn’t take long to empty—there hadn’t been much gold to begin with. Étienne handed it back to his mother.

“Be well, my son, and one day buy your way back home to me,” she sang.

Thérèse pocketed the pouch in her dress, picked up the basket, then stood. Jaw firm, she walked away. Étienne ran a few steps to catch up, the edge of his kilt flapping around his ankles, then fell into a half trot to keep pace. The homes they passed kept their doors and shutters closed. With one exception. Madam Bakelé stood at an open window, her rings and necklaces glinting. She leaned to whisper to her husband. He, in turn, leered, revealing a row of metallic teeth.

Étienne eyed his mother. She kept walking, unblinking. The small, snail shell–shaped earrings she wore were the entirety of her gold. The rest she had given to the tree. His bracelet pressed into his skin. Did it weigh more than it had a moment ago?

Gold changed everything in Deng Deng. That’s what Dieudonné had said. Before the mines, the village was just a place to grow yams and hunt bushmeat. Now Plain Dwellers, Coasters, even some men from beyond the deserts of the Far North, came to dig or to trade. They brought with them new spirits and strange rituals sung in languages Étienne didn’t understand.

He looked back at the Moabi tree. Everyone born in the village knew about the spirit that lived at the heart of the Tree Between Worlds; the ladder that connected soil and sky. Offerings made to it were sacred, untouchable. The gold would be safe there, until rain and wind took it.

But would a Coaster, who worshipped waves and slept with fish-headed women, care? What would happen to his brother’s soul if his offerings were stolen? Dieudonné—the wide mouth that found easy smiles, thin limbs that knew surprising speed, arms that had wrapped a seven-year-old Étienne crying out in the night for a dead father when he himself ached for that father’s embrace—lost forever.

Best to think of something else.

“Maman?”

She didn’t look down as they approached the mud walls of their home.

“Maman, remember when Dieudonné thought he found a gold nugget the size of his ear in the river, and was telling everyone, and then tried to sell it to the exchangers, but it was a—”

His mother pushed open the door and went inside. The rideau—less a curtain and more a scrap of fabric his mother had tacked above the doorjamb—swung into place, brushing his cheeks.

Étienne swallowed, then stepped inside, blinking as his eyes adjusted to the dimness. His mother lay on her bed, eyes closed.

“Maman?”

Silence. The crushed grass odor of day-old kelen-kelen reached his nose. His stomach rumbled.

“There’s stew. I can—”

“Not hungry.”

Étienne backed away, deciding silence was the safer reply.

Stepping to his cot, he unwrapped the kilt from his waist. He paused at a pile of Dieudonné’s clothes folded in the corner. For a moment he considered putting on the shirt. It was silk, after all, black and shiny. A shame to just let it sit there. But it wouldn’t fit. Dieudonné had been tall, lean, all muscle, and long limbs. Étienne looked down at his own arms. Too thin, he thought. And his ribs; he hated how they poked out on his thin chest, how his legs were short but no thicker than sugar cane stalks. He touched his cheeks and jaw and wondered when their boy smoothness would sharpen like Dieudonné said they would.

He slid into a pair of shorts then looked around the room, wanting something to distract him. He could read? No, too dark. And, wary of the tension in his mother’s voice, he wouldn’t risk the disruption of lantern light. Perhaps Monira could play? He took a step toward the door before deciding against it. He was supposed to be in mourning. Besides, when he saw her yesterday in the market, her older sister had hurried her off in the opposite direction.

Still pondering how to fill the rest of the evening, he teased the bracelet off his wrist to twirl it on his fingers. It glowed, capturing all the light in the room. He tossed it up. It landed awkwardly on his palm, the pure gold pressing into his skin, before it clattered along the ground.

His mother propped herself up with an elbow. “Stop it.”

Étienne scrambled for the bracelet. His mother’s beetle black eyes flashed in the semilight as she stared at the gold. “I’m taking it to the exchangers.”

Étienne’s stomach dropped.

“But … he gave it to me.”

“It got him killed.” She lay back down, then rolled over, her back to him. Her whisper was knife sharp. “Haven’t you done enough already?”

Étienne stared down at the bracelet. He wouldn’t give it up, not this last thing. Wiping his eyes, he ran through the door into the fading twilight.

There was only one place she wouldn’t find it.

The forest ended at the digging field, where mines churned the soil like bubbles in a porridge. He ran on despite his mother’s warnings galloping in his head. Don’t you remember what happened to your father? Never go to the mines, agreed?

The graying sky still gave enough light for Étienne to weave between tents and shacks that sprung up between mounds of gravel. Dust tickled his nostrils and became mud as it mixed with the sweat between his toes.

He slowed as he passed a panning pool. Two lanterns hung on poles illuminated a woman and four children sloshing dirt in yellow water. They didn’t look up. After the lantern oil was spent, they would burn candles. And after that, they would work by moonlight. Only finding gold would interrupt their progress.

He hurried on. The mines thinned as he neared the far side of the digging field. He stopped, scanning the horizon. The tree line stood dark against the sky. Odors of damp leaves and night flowers wafted from the woods. Birds chittered.

Étienne found the mound dotted with brown grass. He scrambled up to its crest, then peeped over its edge. Vertigo tickled his senses.

At the bottom of the far side, a mine, its entrance as black and puckered as the mouth of a toothless old woman. Rotten planks crisscrossed its opening. Five boulders painted with red warning charms encircled its rim. One for each man it had killed, the largest for his father.

The mine was smaller than he remembered. His mother hadn’t let him watch the rescuers pull his father’s body from the ground, but he could still feel his brother’s hand clapped over his eyes, still hear the miners’ wives wailing. After that day, his mother refused to let them come to the digging field and forbade Dieudonné from ever working in the earth. She insisted, even when she had to knock at Madam Bakelé’s door to ask for leftover stew or yams that had gone mushy and brown.

Étienne kicked a pebble into the shaft. It bounced against a boulder then vanished into the dark.

Cursed. That’s what the miners said after his father’s funeral. They thought they whispered, but honey wine had made their voices loud and rough. Not a mine at all. The gullet of a dark spirit hungry for human flesh. Or perhaps they had dug too deep, pierced the sky of another world, one full of monsters with mouths for eyes.

No one came near anymore.

Crouching, Étienne scooped out handfuls of gravel. He pulled the bracelet from his arm. Stood, then froze.

A lavender light blossomed over the gravel pits and tents at a far corner of the field. At its center, the naked body of a man, stretched so thin he was little more than ribs and hips under skin. He moved forward on twelve elongated arms, desiccated legs swinging in the air. Scythe-long fingers dug into the earth, grating against the gravel or dipping into panning pools as he scuttled. Four heads swiveled on sinewy necks. One bent low to examine a pile of rocks while two others twisted toward Étienne. It fixed him with sockets empty save for a single white spark where irises should have been.

Étienne told himself to run but couldn’t move.

“You see? Oui, déjà vu, déjà vu and disregarded,” one head muttered.

“Wrong things done,” said another.

A third answered, “Mal fait et mal fabriqué, badly done and poorly made, this snakeling, ce serpent.” Then all giggled, creating the cadence of rain on a tin roof.

“Oh, The One That Sees, do you see gold?” The woman in the panning pool leapt from the water, hitching her skirt to run toward the spirit. Étienne grimaced at how she pushed her words through her nose, giving her voice a lilting accent. A Westerner.

The children followed in a giggling pack. Moto oymonaka, One That Sees, spirit of truth, ignored them.

“Tell me where it is, and I will make you happy.” The woman peeled off her blouse. “I will please you, spirit.”

Two heads turned to her. “Chair, chair, she thinks you want flesh.”

“Pas de tout, nothing so simple. Plus, sweet, deeper still.”

“Flesh, chair.”

It stepped over her. The children gasped and twisted their hands to admire how its light painted their skins purple.

The Western woman arched her back and shook her breasts. Her gyrations exposed her ribs, the sharp edges of her shoulders, the too-visible muscles of her torso. The One That Sees moved on, its long strides carrying it ever closer to the waiting embrace of trees.

The woman’s voice cracked. “Please, spirit, just a nugget or two, or even a flake. For my children to have bread. Just show me where to dig, and I will.”

The One That Sees’s mutterings mixed with the calls of night birds. Étienne would have laughed if fear hadn’t gripped his throat. He didn’t know what the spirits of the grasslands of the West were like, but the ones in Deng Deng had no interest in coupling with humans.

It was hard enough just to get them to answer prayers.

The woman dropped her arms. For a long moment, she stared at the spirit’s receding light. Finally, she bent and picked up her clothes. As she wrapped her blouse around herself, her gaze crossed Étienne’s. Her eyes flicked to his hand, still outstretched and holding the bracelet. Étienne pretended to look in another direction as a pepper-oil heat rose on his cheeks.

“So, it won’t help me, but it will let you thieves keep that?”

Étienne looked up to the Western woman glaring at him. Her children, halfway to the panning pool, paused to watch.

“I know who you are,” she called.

Étienne turned away.

“Oi!”

He chanced a glance over his shoulder, but the Westerner wasn’t looking at him. She cupped her hand to her mouth and called, “Spirit, I found a thief.”

The word struck him like a knife. That’s what they called Dieudonné, before they killed him.

But Étienne didn’t have time to reply, not even to run. The One That Sees paused, then turned. Eight sparks glowed where eyes should have been.

The woman pointed at Étienne. “You’ll let him keep that, but you won’t help me to find even a speck of gold in honest work?”

The spirit’s purple haze shimmered. Then with the speed of a spider scuttling to a fly stuck in its web, The One That Sees darted forward. Étienne took a step back. Rocks slid from under his foot.

“You stole,” asked one head.

“Voleur, alors,” said another. “So, a thief.”

Étienne shook his head. His bladder was suddenly full.

The woman pointed at Étienne. “His brother stole from the exchangers, great spirit, and that bracelet was—”

A head swiveled to the Westerner. Its glow flashed midnight black. The woman cowered, hands raised in supplication.

“Show,” the head facing Étienne said.

Étienne couldn’t move.

“Montrons! Let’s see! Montrons!”

Étienne offered the bracelet with a trembling arm.

“A—a gift, spirit.” His voice was weak as undercooked egg. “From my brother.”

The One That Sees extended a gray tongue. It lapped the bracelet, exploring its curves and edges. Étienne gagged at the smell of dead leaves. The spirit’s eyes flickered. “I see. Seen and lived. Vu et vécu.” It reared upright. Black pulsations wrapped around its limbs, lightning crackling at its many fingertips. Wind whistled over rocks and tore up dust.

“Stolen and violated! Volé et violé,” one head howled. The others picked up the chant.

“Stolen.”

“VOLÉ.”

“STOLEN!”

The woman yelped and pulled her children to the ground. Pebbles bounced around their heads.

“Give to us.” Arms swooped for Étienne. “Undo. Make right.”

“Please, I—” Étienne clutched the bracelet to his chest. A hand trailing white sparks darted for him.

Étienne leapt aside—and the rocks underfoot gave way. As his stomach leapt into his mouth, he remembered how Dieudonné had handed him the bracelet on his birthday over supper, how the lantern light flashed on the snake scales. How his brother smiled, and said, “We’re Snake Clan, see? When I’m in the city, or away trading, or if you go somewhere in this big world, remember that. You, me, Maman and Papa, all our aunts and uncles, we’re one family. And we’re special, because snakes never die, not really. They just shed skin and start over. So, if something happens, we’ll always come back.”

But Dieudonné didn’t come back.

Dieudonné’s smile lingered as the world inverted, as rocks tore into Étienne’s elbows and shoulders, as the smooth surface of the bracelet slipped from his fingers. The planks barring the mine’s entrance withstood his weight only a moment. As they shattered, he wondered if this was how his father felt. Or Dieudonné, at the end.

He didn’t scream. He only tensed his muscles for the inevit——

The maelstrom ended. The Westerner, Sandrine, blinked dust from her eyes, then counted the children under her arms. Four, all there. Balled up and whimpering, but there.

Sandrine forced a smile. “All over, it’s OK.”

The One That Sees stood at the crest of the gravel mound, its purple glow tranquil as spring flowers. One head bent over the far side of the mound. It plucked up a shining something from a cluster of weeds.

A bead of sweat prickled Sandrine’s brow. The boy with the bracelet was gone.

“Ancestors.”

She only meant to encourage the spirit to tell her where to find gold. Spirits so rarely did. And the boy was just standing there, showing off his wealth when she was just trying to work, but she hadn’t wanted …

Spirits in Deng Deng didn’t eat people, did they? But where else could the boy have gone?

As soon as they had enough money, she would buy a chicken and take it to Woman of Ten Thousand Fingers for purification. No, two chickens. And a pot of honey wine.

Sandrine rose as the spirit shuffled toward her. She swallowed down the urge to gather her children and run.

The One That Sees stood over her. It blinked its starlight eyes.

“Great spirit,” she said. Her voice quavered.

It dropped something that clinked near her feet. Sandrine, her gaze trained on The One That Sees, stooped to retrieve it. Her fingers found the curved edges of a bracelet. Heavy. She examined it. A snake motif etched into the band stared back with geometric eyes.

“Made right,” one of The One That See’s heads said.

“Comme tu as voulu,” said another. “As you wanted.”

Then it shuffled into the forest, its glow slowly fading behind mahogany trees.

Sandrine looked down at the bracelet. For a moment she lifted her arm to throw the thing away.

But gold was gold.

“Ancestors, forgive me.”

The Second Day

Of the dozen sensations that tugged at Étienne, thirst stirred him to consciousness first. He opened his eyes. Closed them. It made no difference in the dark.

He sat up, then regretted the movement. The back of his head throbbed. His side protested each breath, but his right arm was worse—like glass digging into his bones. A wave of nausea washed over him. He lay motionless until it passed.

He brushed fingers along the surface of the mine. Chisel marks cut parallel grooves into the stone, as regular and tight as a rib cage. How long had he been down here? Minutes? Hours? He smacked his mouth. Longer?

The image of the toddler who fell into a shaft the year before bubbled up through the fog in his brain. Her twisted body, the odd angle of her neck, her glazed-over eyes.

How would he look when they finally pulled him out?

If.

He forced his heartbeat to slow. It would be fine. The Westerner saw him fall. She’d send for help.

But hadn’t she called a spirit to punish him? His stomach roiled. What if The One That Sees was waiting at the mouth of the mine like a dog guarding its dinner?

His mother. She would know he was missing; eventually she would find him. Spirit or no, she would free him.

But what if she woke up to find him gone and was glad for it?

He didn’t fight when the vomit rose again. The sourness of sick and blood filled the shaft. He sat for a long moment after the spasms passed. He looked up, straining to see even the faintest glimmer of light. Nothing. How many side tunnels or dead-end shafts had he tumbled down? If someone came into the mine, they might climb past him, and he would never know.

“H-ell-o?” He swallowed, winced, called again. “Hello?” Louder still. “Hello?” His yell died in the blackness.

Then, a tear prickling the corner of his eye, he whispered, “I’m sorry.”

The reply came on a voice soft as moth wings. “I know what you’re sorry for, little one.”

Étienne yelped. He swatted the air, striking nothing. Laughter like dry leaves rustling filled the dark.

It was true. There was a spirit here. Was this voice the last thing his father heard before stone and dirt swallowed him? It took a moment for Étienne’s lips and tongue to coordinate sound.

“Please don’t eat me, great spirit.”

“Eat you?” The whisper laughed again. “Don’t you know me, boy?”

Étienne hesitated. He knew many spirits: tree spirits and river spirits, spirits of healing and spirits of witchcrafts. There were night spirits that shied away from humans, and day spirits that were as involved in village affairs as the elders. But all gave light. None hid themselves in mines.

“You are the spirit of this place?” He meant it as a statement but couldn’t keep the question out of his voice.

Its snort was the breaking of branches in a storm. “I am much more than this hole, little one. You know me and my name.”

Know it? Étienne’s mind sped through spirit names, some as familiar as the members of his own family: Weeping Man, He Who Sleeps Under River Stones, White Woman. Names of shyer spirits rarely encountered: Child of Rainstorms, The One Without Faces, She Who Laughs at Night. This was none of them.

“Think,” it said. “What happened to you?”

“I fell.”

“Yes, and?” the whisper intoned.

“I hurt myself?”

A sigh. “A riddle for you then. I am carrion beetles feasting on what was.” The mine echoed with the chirp of carapaces and biting mandibles. “I am glass-toothed hunger swimming under black waves.” A scaled fin grazed his leg. “I am the gaps between stars, the nothingness beyond nothing.” The stone walls around him vanished, taking away all sense of up or down. “All things come to me in the end. Because in the end, I am all things.”

Étienne saw through a thousand, thousand eyes; as wolves devouring a deer, as a pestilence gnawing unseen on flesh, as worms digging through Dieudonné’s burned corpse in a communal grave, as the sightless skull of his father still wrapped in a moldering death shawl.

He dry-heaved. He’d never seen his brother’s body. It was his mother who told him that a mob in Port City had cornered Dieudonné in an alley. It was only through whispers overheard in the market that he’d learned the whole of it, that after they beat his brother, they set him on fire. And when his brother was dead, they tossed him in a pauper’s grave, like so much city refuse. He hadn’t imagined the burns would … Hadn’t pictured … He hoped his brother was dead before the flames did that to his skin.

“O Ancestors, Dieudonné.”

The images melted to blackness. Étienne curled into himself, sobbing despite the pain it brought his ribs.

“So, what am I, little one?”

He knew. The formless spirit of one name. The one who all would see only once but could never speak of again. The spirit above all spirits.

“Death.”

Thérèse hated that the morning promised to be so beautiful.

Dawn wove its way through the forest canopy, gilding leaves and turning dew to silver vapor. The trill of songbirds melded with the ululations of cloud spirits fluttering through the highest branches, announcing their ecstasy at the return of their wife, the sun. On the path before her, a baker pushed a cart loaded with steaming rolls and bottles of yogurt.

“Hot, fresh, hot. One cowrie, two cowrie, hot, fresh, hot.”

Thérèse shuddered. The hawking song might as well be a funeral dirge. She wished she could plug the throat of every bird and hurl the sun back over the horizon, anything to slow the arrival of a day where one son was dead and the other missing.

She cut through the garden to Madam Bakelé’s door, crushing a fledgling tomato in her haste. She pounded on the wood slats with both fists. Madam Bakelé opened it, winding a wrapper over her hair. Her skin gleamed with freshly applied shea butter.

“Give me three buns, Henri, and one—Thérèse?” Madam Bakelé’s face went blank. She was a tall woman, with wide, rounded hips and shoulders. She filled the door, but Thérèse sensed her neighbor pull into herself like a snail retreating into its shell.

“Have you seen Étienne?”

“Hmm?” Madam Bakelé’s gaze darted around the road and neighboring houses. The baker in the street resumed his refrain as he rounded a corner.

“Étienne. He didn’t come home, and it’s been all night. Have you seen him?”

Madam Bakelé inched the door close. “No, no.”

“Please.” Thérèse pushed the door wide. “I’ve been to the market, the neighbors, no one has seen him. I tried the exchangers first, to see if he sold the … Never mind. But with your house so close to the road, I thought maybe you, or your husband—”

Madam Bakelé reached up to release the rideau. Its yellow and blue fabric flopped down into Thérèse’s face.

She swatted the drape aside in time to see Madam Bakelé dart through her kitchen and out the back door.

Thérèse stood open mouthed, blood pounding in her temples. Did none of them care? Would all of Deng Deng punish Étienne for Dieudonné’s mistake?

She turned back to the road. As she crossed the garden, her foot grazed a pepper plant in a clay pot. She stopped to study it a moment, admiring its red fruits, each a red lip grinning up at her. She picked it up, hefted it.

With a grunt she hurled it against Madam Bakelé’s rideau. It went wide and clipped the doorjamb, exploding in a shower of soil, leaves, and pottery.

Straightening her shoulders, she started back down the road to the village center. Did anyone see? If they did, so what? Give them more kongosa, more gossip. Let them whisper she had lost her children, her mind. At least that way they wouldn’t forget she had sons.

Exhaustion tugged at the back of her eyes. Hadn’t Dieudonné been their son as much as hers? Hadn’t he suppered in their homes, too? And look how they took his death, as if he never existed at all.

She brushed away a tear threatening to fall from her cheek. So much for neighbors. None had even come to sing at the Moabi tree. Its sprawling canopy cast a shadow over Deng Deng. She let her eyes trace the familiar smoothness of its trunk, down to where just yesterday she and Étienne had—

“No.” She hitched her dress as she ran to the tree. “No, no, no.”

She fell to its roots, running her fingers over score marks where bark had been shaved away. Yellow sap stuck to her skin. Every flake of the gold she offered the Tree Between Worlds was gone.

“White Woman!” She spun, yelling at the forest. “White Woman, I call you!”

A door at the far edge of the village slammed shut. Birds ceased chirping.

“I am a daughter of Snake Clan, I call you. By all the rites and oaths, I demand you answer.”

A silver glow erupted at the edge of the forest. Thérèse blinked back green spots floating in her vision.

Ten mouths spoke in ten voices melded into one. “Oaths? Rites?” Solid blue eyes glared at Thérèse as the spirit strode forward, her silver hair whipped by white flames and shards of mirror glass. A robe of spiderwebs billowed in her wake.

“She breeds thieves but makes demands of White Woman’s good promises? Wrong, wrong. So very wrong. First son a spoiled seed. Plucked him like a weed.”

Thérèse dipped her head. Not low enough, but where had patience and deference gotten her family thus far?

“My eldest has nothing to do with this, great spirit,” she said. “I come seeking his brother. Étienne. He’s lost.”

White Woman sucked at twenty rows of teeth. “Do we tell her that the little boy knew? That he knew his brother worked in the dark, in the secret and the dark? That he stole like rats steal table scraps? Do we tell her?”

“I forbade him.” Thérèse looked up. White Woman twirled, her hands wheeling in the air.

“The One That Sees saw. See and saw. Saw and seen. Truth came out, quick and clean. It always does, with The One That Sees. That’s why they curse him.”

Thérèse’s breath caught. “He saw Étienne? Where?”

White Woman’s lips curled into a wall of smirks.

“Tell me!” Thérèse’s step forward earned a warning flash of black lightning. She bowed her head and forced her voice to remain even. “Please, Keeper of Snakes, where is my son?”

Two mouths wailed while the others bellowed, “Who speaks? We don’t know. We forgot the voice. Not a snake, not a child of the scales. Tell this stranger to leave us, leave us and die, because that is all she’s worth.”

White Woman’s light rippled as she spun away, leaving Thérèse at the ruined roots of the Moabi tree.

She rubbed her eyes, surprised to find them dry, and more surprised to find her heartbeat slowing. She had her answer. Deng Deng wouldn’t help. The spirits wouldn’t help. Had they ever? What more did they do than dance and demand sacrifices in exchange for what? Cryptic mutterings and pretty colors.

She should have seen it sooner. The spirits would have demanded a blood penance for the mutilation of the Moabi tree. It was only because they had never accepted the offering of gold flakes in the first place that they allowed it to go unpunished. Better to let the tree be scarred than to have it be tainted with an offering made for one such as Dieudonné.

Scales rasping on wood sounded near her feet. She looked down at a python winding itself over tree roots. It paused to flick its tongue at her, like the wave of a minuscule purple hand.

The image of the two snakelets whipped through her mind. Sibling.

“You don’t know where my son is, do you?”

Étienne’s face filled her mind. He looked down at her, the Moabi’s canopy spreading over a twilight sky. The python’s memory of the funeral.

“Yes, brother. Have you seen him?” Thérèse leaned in, her heart thudding. Perhaps—

But the snake slithered away. She watched the beige point of its tail vanish into shadow and dead leaves.

Fine. If spirits and villagers and snakes wouldn’t find her son, she would.

Her son’s last memory of her wouldn’t be her yelling at him.

She started down the path to where she did not know.

Étienne didn’t know if he slept. Had he spoken to the spirit of death only for it to vanish at its name, or was that a dream? Was that minutes ago, or hours? Or was this darkness the dream?

“Tell me, little one,” said the voice smooth as pond water. “Why are you down here?”

No, this was real. No dream could be this terrifying.

“Well?” Death asked.

Étienne weighed his response. Did she know the answer already, or did she only want to know how he would respond? Any reply was a gamble. “I was pushed.”

“Pushed? Oh my.”

“Yes, Great One. I wasn’t supposed to be there. I was trying … Well, I had this bracelet—”

“Pushed? Fell? Jumped? It doesn’t matter.”

Étienne hadn’t realized he was straining upward until he slumped back against the mine’s wall.

“How you got here, little one, is unimportant. It is not up to me to intervene, only to follow the course of actions put into motion. You have heard my voice—your path is set.”

“My mother—”

“What about her? All die. All come to me in the end.” Death’s voice tickled his ears. “Your brother is here, your father, too. Join them, here in the dark. Why fight?”

Colors crashed through his headache, swirling to form the image of a snake, fangs at the ready, waiting for a bird to hop by. A sensation of question accompanied it. Why not patience?

The mental image vanished. Étienne jerked as scales slithered over his shoulders. Pulsating coils drooped over his chest and arms. A tongue flicked his ear. He relaxed. He had no reason to fear, not as a son of Snake Clan.

“White Woman is coming,” Étienne said. This snake was a sign, sent to watch over him until rescue came. The One That Sees had told White Woman what happened. As Snake Clan patron, she would have told his mother. And the village; they would pull him out, he would be free. Maybe Madam Bakelé would stand in the crowd and cheer, her gold flashing as they pulled him from this pit. Or his mother, she would throw herself at his feet to beg his forgiveness. Étienne giggled. “Oh, thank you, brother.”

“This is none of your concern, dirt eater,” Death said to the snake.

Identical snakes coiling around each other. The reassurance of trust washed over Étienne.

“When is White Woman coming, or my mother?” Étienne reached to stroke the snake’s head. It was large and bulbous. A python. The one from the funeral. Étienne giggled again. Why had he reviled snake voices so much before?

The snake moved away, coiling itself over his shoulders and arms. The images and emotions fell in quick succession: Étienne’s mother. White Woman. Discomfort. White Woman’s silver fire. Anger. Sadness. Abandonment.

Death snorted. “Then, leave.”

Étienne barely heard. “Tell them I’m hurt. And thirsty. And my bracelet, I think I dropped it.”

The snake tightened its coils, just enough to smother another giggle rising in his chest.

White Woman’s smile, then her grimace. A tree branch snapping in two. A mother snake swallowing her eggs. Loss. Betrayal.

Étienne struggled to put the images and sensation into context. Betrayal? How? He hadn’t betrayed anyone. The obligations with White Woman were ancient ones, forged with spirits generations ago. To break them he would have had to …

“Broken? She’s not …”

A feeling without imagery—regret. No.

The disappointment in Étienne’s chest didn’t come from a snake. Neither did the embarrassment and anger that followed.

White Woman didn’t care. Why would she? When she’d ignored the funeral rites for Dieudonné? Étienne blinked back hot tears. “So go and tell my mother where I am. She’ll send help.”

White-hot fire and White Woman’s ten screaming mouths. Fear.

Death’s chuckle was the beating of bat wings under a moonless sky. “See, little one? Not even your patron spirit will alter what must be done, and your little friend won’t challenge her.”

Étienne ignored her. “Then why are you here,” he asked the snake. “To watch me die? Feed on me like a cane rat?” Étienne squirmed against the python’s coils around his neck, tight as a noose. He relented as bone ground against bone in his arm.

The standard greeting, twin snakes born from the same egg. Trust. Then a question.

Étienne said nothing. Of course, he knew the stupid story. Everyone in Snake Clan did. It was their bedtime story, told night after night to children to explain why Snake Clan was different from River Clan or Cloud Clan or Sky Clan. He braced himself.

The images poured through his head anyway. A python, dappled green and brown, winding its way through the forest. Its way blocked by a river of sharp-jawed army ants. The arrogant snake trying to push his way through. The swarming, the biting, then the pain. Shouts of help to the spirits, the silence that answered. And just as the snake thrashes and prepares for the end, a man runs to him, lithe as a panther. Beti. Étienne’s ancestor. His skin gleaming, muscles rippling, eyes like sunlight through trees. The man’s hands pulling the snake from the ants, despite the pain it brought to his soft, unscaled flesh.

A sensation of relief. The snake’s question. Why? The man’s simple response. A finger pointing to the snake, to himself, then to the blood that oozed from the cuts and bites on their skin. You. Me. Same.

Then the promise. The snake winding its way around the man’s arm, the sharing of souls—blood to blood, flesh to flesh—Beti’s warmth healing the snake. The bonding that forged Snake Clan.

Darkness swallowed Étienne once again.

“Such sweet lullabies,” Death said.

The python’s hiss echoed until the mine sounded like a hornet’s nest. More images flew through Étienne’s mind like a whirlwind of color. A baby snake. A human child crawling on the ground. Sibling. Anger. White Woman.

Étienne shook his head. “I don’t understand.”

A sandy colored deer in the forest being shot by an arrow. An old woman sleeping in her bed, her gray braids dangling like vipers from branches. Trust. Courage. Loss.

“Please, I’m sorry, I’m not …”

We. Brothers.

Étienne’s mouth opened. He hadn’t heard the words, not with his ears. They were in his head like the pictures, but speech? Without images? From a snake? Was that even possible? In all the stories, and all the elders they never—

Please. Listen. Talk. So slow. Get words upside down.

“You mean ‘wrong,’” Death said. “But bravo for trying. Keep up this pace of evolution and you may grow legs.”

The python ignored her. You ancestor. Mine ancestor. Promise made. You hear me. I hear you. Before White Woman. We promise stronger promise White Woman.

The snake slithered onto Étienne’s lap, curling against his stomach.

Me afraid White Woman. But she listen to snake. If me tell her, you good. You brother. You need save because good. White Woman change mind. Spirits help. Then a sensation of confidence so strong it was warm.

“You think this little human is good?” Death’s laughter showered Étienne in pebbles and dust dislodged from the mine’s walls. “Shall you tell him, boy, or shall I?”

The image of a snake slipping from a tree branch, its tail whipping out uselessly. Confusion. Tell?

Étienne blinked dust from his eyes. No tears came. He had no more to give.

“I killed my brother.”

The Third Day

The clunk the snake bracelet made on the exchanger’s stall was gorgeous. Solid and heavy with the promise of a month’s worth of meals for Sandrine and her children. Maybe two, if she haggled well.

She resisted the urge to pluck it back up just to drop it one more time.

“Moment,” the exchanger said. He continued to stare at a lump of rock through a jeweler’s loop. He was short, hunched over, his form hidden under a gray silk shirt much too large for him. Sandrine thought he looked like a bird perched on a stool. A pigeon, maybe, with those tiny eyes.

Sandrine bounced from foot to foot and glanced behind her. Her four children stood at the edge of the exchanger’s stalls, tickling each other with tufts of elephant grass. On the road next to them, men with cudgels carried away iron boxes, heavy with unrefined gold dust. Nearby, a bush spirit with lily flowers for eyes and vines for arms swung from stall to stall, leaving a trail of petals.

After a long minute the exchanger turned and picked up the bracelet.

“Intriguing piece,” he said. He muttered under his breath as he tested its weight on his fingers, nibbled an edge, twisted it under his loupe. “Fifty, no, forty-nine grams, decent craftsmanship, all good. Hmm. And this motif?”

“Yes, yes, very pretty. How much will you do me for?”

The exchanger set the bracelet down.

“How, might I ask, did you come by this piece? Given your, well, origin.”

“My what?”

“This was made for someone of Snake Clan. And I don’t believe they are found in the West.”

“Spirit gave it to me.”

“Oh?”

Sandrine pursed her lips. She’d come to this exchanger, here at the edge of the market, because he had a certain reputation. Few questions, a short memory, and bad record keeping.

A reputation that wasn’t being well earned today.

“I got hungry little ones, and it took a fancy to me. Now are you going to give me cowries for it or not, ’cause I see lots of other stalls open today.”

“You see,” the exchanger said, leaning back on his stool, “there’s a rumor going around. About a Snake Clan item. Stolen, apparently. And the current possessor, a mere boy, has vanished. The mother is distraught. Ancestors watch over her. But if you say a spirit gave it to you, well.” He smiled then, but there was no mirth in his lips. “But what kind of business would I be running if I didn’t verify my purchases?”

“What?”

“They of the Deep Soil? Please, this way.”

The exchanger motioned for the little green bush spirit. Sandrine took a step back as it swung to them like a monkey moving in the canopy. It stopped at the stall, petals falling onto the table. Sandrine expected lily perfume but found only the reek of swamp water.

The spirit’s eyes blossomed as it looked at Sandrine, the petals opening and closing as it blinked.

“La honte, guilt, she smells de la honte, this one of the grasslands, cette femme of not here.”

“Guilt, good spirit?” The exchanger leered. “About what, I wonder?”

The spirit cackled and swung around.

“I—I didn’t steal—”

“Should we take? Mais oui.” They of the Deep Soil caressed the bracelet with a vine. “Not stealing if you steal d’une voleuse, from a thief.”

Sandrine tried to speak but couldn’t look away from the petal eyes. She knew bush spirits back home. They were gentle, mostly. Always sleeping in someone’s garden to help the manioc and taro grow. Kiss one and it would grant you favors. Do a bit more than that and you’d earn a miracle. But this … It shouldn’t be here, in the barren market where all the plants had been cut down. Chittering like some animal.

Maybe it’s Deng Deng, she thought. There’s something bitter about the spirits here—bitter as the soil, the mud, the sallow faces staring back from the exchanger stalls. Or perhaps it was the people. They turned up the earth for gold and set everything rotting.

Sandrine snatched the bracelet and clutched it to her chest. “Go ask The One That Sees. Question it. See how the spirit of truth likes being called a liar.”

The exchanger stiffened. Sandrine backed away, aware of every eye, of how the market had gone silent. She spun and collided into a woman.

It took all her strength to keep her knees stiff. Because it was that woman. The one she’d been dreading seeing.

The one who’d been wandering the market, the digging field, the houses, shouting and mumbling, “Have you seen my boy? My son?”

The mother of the boy.

Sandrine swung the bracelet behind her back. Too quick, she thought. Too obvious.

But the woman shuffled past Sandrine, unseeing. Her hair jutted out at odd angles, and dust stained the hem of her indigo dress. Sagging skin clung to her cheeks. She looked like a rag doll that had escaped a dog.

“Have you … my boy?” she said to no one in particular.

Sandrine didn’t pause to watch her. She ran to her children, grabbed her youngest’s arm, and tugged him to the road. The boy whined in protest, but she didn’t slow.

They of the Deep Soil called after her, their voice a squealing sing-song. “She watched him die and rien de tout, not a thing, so she could eat, pour qu’elle puisse manger, manger. She watched him fall down, down, down, she could eat his gold, this one of elsewhere, cette femme d’ailleurs.”

By the time Sandrine reached the road, she was crying.

Étienne sniffed, glad for the darkness hiding his face. But with Death and a python sharing his thoughts, did it matter?

The image of a snake slipping from a branch. Disorientation. Confusion. What?

“I didn’t—” Étienne swallowed down a sob but his mouth was ash dry. “I didn’t mean to.”

How kill brother?

Death snickered. “Yes, do tell.”

Étienne shifted, grunted at the stab it brought to his arm. “It was … I only … I only wanted something that people would look at. I thought it would be nice, to have, you know? I’d never had anything like it.” He took a breath. “So, when Dieudonné came to see Maman, I—”

The python squeezed its coils. Étienne’s mind filled with a cane rat bounding over a rock, its haunches just out of reach. Frustration. Missed. Be slow.

Death’s groan was the grinding of rocks. “I thought you humans loved stories. Why are you so bad at telling them?”

“I’m just trying to—”

“To what? Humans have such bent perceptions, anyway. Always tilting the light to show off your best features.”

A presence swam inside Étienne. Like the thoughts of the python, but slower, cooler. His thirst faded, and the ache in his arm calmed to a dull throb.

“Perhaps a more neutral gaze, shall we?” Death said. “Now, sit back.…”

A light grew in the mine’s darkness, gray at first, then fracturing into reds, oranges, blues. Shapes emerged. A window, a red adobe wall, a faded rideau swaying over an open door. Étienne breathed in. Over the damp of the mine, he detected tangy lye soap, salty fish stew, the earthy raffia rug. All of it melded into that undefinable aroma of home.

And there, in a corner, himself, seated against a wall and thumbing a book. But the angle was off. Higher, as if—

“A mouse was dying in your rafters. I was there.” Death snickered. “I’m always there, at the end.”

Dieudonné walked through the rideau. A black silk shirt hung over his chest and lean frame, and matching trousers flapped around his feet. A delicate gold chain with a charm—a snake swallowing its own tail—dangled from his neck. It swung counter to his movements, and Étienne thought of dancers.

Your brother? the python asked.

Étienne tried to jump down from this odd vantage point and run to Dieudonné. But he remained fixed in place. He looked to his other self. Move, he willed. Get up.

“It’s just a memory, little one,” Death said. The mocking edge had gone from her voice. “Just watch.”

Étienne’s mother burst through the doorway. Grabbing Dieudonné’s shoulder, she spun him around then waggled a balled-up mass of crimson fabric at his face.

“It’s a good job,” Dieudonné said. “That’s how I bought it.”

“You’re just a courier to Port City. That’s what you said. But Dembele pays you enough to buy this?” Her finger stabbed his chest. “That necklace?”

“I thought you’d like it.”

Thérèse glanced to Étienne reading in the corner. She grabbed Dieudonné’s arm and pulled him behind a shelf full of unripe plantains. Étienne watched his past self steal a glance up, the book now only a prop.

“Are you skimming?”

Dieudonné winced.

His mother stiffened. “Dieudonné … No.”

“A few grams. Dust that falls to the floor of the jewelry shop. Dembele wouldn’t even miss it. Hasn’t.”

Thérèse sank onto a sack of rice and buried her face in the gown.

“How long?”

Dieudonné played with the edge of a raised tile with the toe of his sandal.

“How long, Dieudonné?”

“Long enough to get Étienne some schoolbooks. Food. That.” He nodded to the gown.

“I wouldn’t have taken it if I knew.”

“Fine. I’ll take it back.” He stuck out his hands. Thérèse hesitated, her hands tightening just so. Dieudonné smirked.

Thérèse stood and waggled a finger. “No more, understood? Do you know what these people would do to you if they found out? Do to us? Gold has …” Her brow creased. “I don’t recognize Deng Deng anymore.”

“I’ll be fine, Maman.”

“Promise me.”

“Maman—”

“Promise me.” She stepped closer to Dieudonné, her black eyes boring into his. “Please.”

“Fine, fine.” Dieudonné pulled her into a hug. “I promise, OK?”

They stood for a moment, Dieudonné’s chin resting on his mother’s plaited hair, the gown squished between them.

“I should go, Maman,” Dieudonné said. “Dembele’s expecting me.”

Thérèse sniffed. “Eat first.” She jutted her chin at a marmite simmering on some coals. “It’s a long walk back. I’ll get you a bowl.” Soon the clang of cutlery filled the house.

Étienne’s other self jumped from his chair. In the mine, he squeezed his eyes shut. It did nothing to block Death’s memory.

Dieudonné flashed a grin. “Like the book?”

Étienne nodded, a half-smile teasing his lips.

“What?” Dieudonné asked.

“I was wondering …” Étienne put a hand over his mouth, trying not to giggle.

“Spit it out.”

“It’s my birthday in two months, and …”

His brother laughed. “And what would you like? Another book?”

Please, shut up, Étienne willed. Don’t say it. Just sit back down. Please, please, please.

Étienne could only watch as his past self went on tiptoe to whisper in Dieudonné’s ear, “Gold.”

Dieudonné raised a brow. “Gold?”

“Not something big, or anything. I just thought, if I had an earring, or a necklace, like you, maybe …” He shrugged.

Dieudonné crouched to meet Étienne’s eyes. “Are people bothering you? Because it doesn’t mean anything if you don’t have—”

“I put the piment in with the stew.” Their mother, carrying a bowl wrapped in a sack, stepped from the kitchen. “I know you like it that way.”

Dieudonné stood, too quickly. Grabbing the parcel from her hands, he kissed his mother’s cheek, ruffled Étienne’s hair, then stepped for the door. As he went through the rideau, he turned, winked, and said, “I’ll see what I can do, OK?”

The world shimmered. Colors bled into each other, as if a finger had been swiped over a painting to smudge all the lines.

What happen?

“Just moving things along a bit.”

The room reformed. Étienne, Dieudonné, and their mother sat on the floor around a marmite. Dieudonné, now in an indigo robe, handed Étienne a mass of brown paper. Étienne tore it apart until a glint of yellow shone through.

“A bracelet?” Étienne held it up. “Thank you, thank you, thank you!” Étienne threw himself around Dieudonné’s neck.

Thérèse glared. “You promised,” she mouthed, but Dieudonné waved her off. Pulling Étienne off, he pointed to the bracelet.

“We’re Snake Clan, see? When I’m in the city, or away trading, or if you go somewhere in this big world, remember—”

Dieudonné’s smile faded to gray, then to black. There was only darkness, the damp, a renewed throbbing in his arm.

The python coiled itself into a knot in his lap. What happen? How kill brother? No right.

“Well, Étienne?”

Étienne said nothing for a long minute. “He stole the gold from Dembele. Maybe from the courier boxes when they brought the raw gold to the city. Or took it from the jewelry shop. I don’t know. But I knew he was stealing, and I asked him anyway. His boss found out, and he … They …”

His mind erupted with a new memory. Port City at night. Sleeping ships at a dark harbor. A jeering crowd. Fire blossoming over a body. Flailing limbs.

Screams.

Laughter.

Étienne shoved the crook of his elbow over his eyes.

“I’m so s-sorry. I didn’t m-mean t-t-too—”

The python wrapped around his shoulders. It sent images of cool leaves, shade, warm rocks. Death’s memory faded.

Peace. Peace.

“So, dirt eater,” Death said. “He knew his brother stole, and he asked anyway. Then his brother died. Now all his village knows he and his mother lived by taking what was not theirs. No better than thieves themselves.” Death’s voice hummed in his ears. “So, what do you say? Is he a good person?”

No words, not even an image in reply.

Just a fuzzy gray sensation of regret.

It seemed appropriate to be here, where everything first went wrong.

Thérèse sat on a pile of rubble at the edge of the digging field, her fingers playing with pebbles. She stared at the pile of gravel half covered with brown grass. A wind spirit flitted overhead, its gelatinous body a ripple of green. Its wake carried the scent of rain. Thérèse’s eyes followed it for a moment, then they drifted back to the mound.

Five years and she’d never come so close.

Just an extra shift, her husband had said. “Today I find the mother lode. I feel it.” He’d kissed the top of her head as she peeled manioc root. His beard scratched her, and she’d mumbled a goodbye as he walked away. She hadn’t looked up. Hadn’t said goodbye. If she could—

Something whirled past Thérèse’s legs and clanged against the ground. It bounced, glimmering, then landed behind a rock.

She looked up. A woman stood over her. She had red, swollen eyes and a thin head perched on narrow shoulders. Resewn patches covered a purple skirt. Her lips trembled, and when she spoke, her words stuck in her nose. A Westerner.

“Just take it. I—I can’t. All day and … I don’t want— It’s not worth it!”

“Huh?” Thérèse wasn’t sure if it was the woman’s accent or her own exhaustion that was making everything muddled.

“That! All day it’s been following me. Singing!” The woman pointed at the forest. Thérèse followed her finger to where a small, green bush spirit had wrapped itself around the trunk of a mahogany tree. Lily petal eyes blossomed as it grinned, then waved a vine.

“Cette femme d’ailleurs, this otherwhere woman, she watched him fall, down, down, so she could mange son or, eat his gold, mange, mange, mange, yum yum.”

“See? So take it. I don’t want it anymore.” The woman wiped her eyes, turned, and started down the path to the village. A group of four children joined her, their wary eyes darting to the spirit lurking in the forest.

Didn’t want what? Thérèse looked around for what the woman had thrown. Something metal. She thought she’d seen it wink in the light and—

Her fatigue vanished. With unsteady fingers she reached down and picked up a bracelet. The rocks had scratched the edges, but the snake motif stared up at her.

“Wait.” Thérèse’s voice cracked. She rose and the world threatened to invert itself. “Wait!”

The woman and her children kept marching toward the village. Thérèse ran. Once, she stumbled, fell, then rose again, ignoring a throb in her elbow. She grabbed the woman, spun her, and brandished the bracelet.

“Where? Where did you get this?”

The woman refused to look at it.

“My son, where is my son?”

The Westerner began to cry. Thin, halting gasps that became sobs. Thérèse stepped back, wanting to both shake the woman and embrace her. Tell her she knew pain, too.

After a moment the Westerner let out a long breath, then met Thérèse’s eyes. “There was a spirit. The One That Sees.” She went on, saying her name was Sandrine, that she’d come to Deng Deng from the grasslands with her children. She told Thérèse how they’d been so hungry for so long, so when a spirit came, she offered herself to it, but it ignored her. It angered her, then she’d seen Étienne just watching, playing with that hunk of gold. She’d only meant to scare him. She hadn’t thought the spirit would come back, actually attack him.

“There was wind, and dust. I didn’t see what … When I looked up, he was gone. Just gone. The One That Sees gave that to me, and we hadn’t eaten in so long. I’m sorry. Really.”

Thérèse said nothing. Sandrine’s story didn’t make sense. Spirits didn’t vanish people. Hurt, maybe, if they were angry enough. Chase if provoked. But they had no interest in dragging someone away. Spirits fed on dreams and hopes and wishes, not flesh. If the spirit had only killed Étienne, his body would be there. There’d be no reason for The One That Sees to hide her son’s corpse.

The bush spirit sang again. “She watched him fall, down, down, so she could mange son or yum yum.”

Fall.

“Where?” Thérèse said.

Sandrine wiped her eyes. “What?”

“Where was he? When The One That Sees came. Where was Étienne standing?”

Sandrine blinked and gestured at the mound of gravel.

“There, I think.”

Thérèse gasped. How could she have been so blind, so stupid? Of course, Étienne came here. The one place he knew she’d never follow. And that’s why Sandrine thought he’d vanished. You couldn’t see the opening except from atop the mound.

The spirit hadn’t taken him; he’d fallen.

And might still be alive.

As Thérèse ran for the mine, she yelled over her shoulder at the confused Westerner, “Don’t just stand there, get a rope!”

The shivering wouldn’t stop. Étienne curled into a ball. His brother’s face swam before his vision, flashing that quick smile that burst into pale yellow flame.

The python looped himself around Étienne’s forehead. No cold. Hot.

“Fever,” said Death.

Need water.

“I didn’t mean to,” Étienne mumbled.

“Stop fighting, little one,” Death said. “Your bones are broken. Your snake sibling has seen what you did. Spirits won’t help you. Your family can’t help you. You have no water, no food.”

Étienne swatted the darkness. “So, laugh. It’s what I deserve, right? This is what I get?”

“No, Étienne.” Concern softened the edges of her voice. The impression of a hen pulling a chick under her wing flickered through his mind.

It didn’t come from the python.

“Your path is set. It was from the moment you fell. Every choice, every action demands a result. I can’t spare you, but you don’t have to suffer. Not like this.”

A star of blue light appeared in the dark. Étienne blinked. It remained, bobbing as it inched closer.

The python leapt from Étienne’s forehead to his lap, its muscles rippling. Étienne winced at the urgent sense of danger flooding his thoughts.

Scorpion.

“This is my daughter,” said Death. The light stopped a few centimeters away. “Her sting offers a quick death. No more pain. No more fever. Just sleep.”

Étienne struggled to focus on the needle-thin pincers, the curved tail. He should be afraid. How many times had his mother chastised him for not checking his sandals before putting them on, or swept under his cot to chase one away? But the creature’s glow was delicate, the curve of its stinger elegant. Comforting, like a candle, or a sliver of moon on a dark night.

“Just a prick, then it’s all over.”

For a long moment, the snake tensed on Étienne’s lap. Then it relaxed.

Rest. Peace. Understanding. No pain. Sleep.

The scorpion clacked its pincers. Its tail curled and uncurled. A beckoning finger.

Étienne eased the python off him, then stood. He stepped toward the scorpion, the pain in his body distant. His father waited for him. Dieudonné, too. Maybe this is what he deserved.

A mercy, this offering.

Then a rope plopped into his face.

The Fourth Day

Thérèse’s soul went with her voice down the gullet of the mine.

“Étienne! ÉTIENNE!”

She held her breath, straining her ears for a reply.

“Hey!”

But not from below. From above. Thérèse looked up as three miners stumbled over the top of the mound. Orange mud clung to their bare chests.

“Get back,” one said. A large man, his biceps like gourds, stopped short of the ring of warning stones. “Cursed.”

“Edge might collapse,” said another, a thin man whose teeth shone like porcelain against his soil-covered face. “Hasn’t been touched in years.”

Sandrine, carrying a coiled rope, elbowed them aside. She offered one end to Thérèse, who took it and bent to the largest boulder set at the edge of the mine. She tried not to think about how the red warning charms painted on them looked like blood. The pit below yawned, wide and black and deep.

As Thérèse cinched the knot, she wondered if this stone was the one that represented her husband. Its red charm was still as vibrant as the day they had pulled out his crushed body.

Strange that today it might help save her son.

Might. If. If Étienne were still alive. If his neck wasn’t broken. If he wasn’t bleeding out, or dying of thirst, or—

No. He was alive. She clung to the word like the last breath of air in a stale room. Alive.

“Move,” Thérèse told the miners.

“Wait,” said the third man, his neck so short that his head was just a lump on his shoulders. He looked from Sandrine, to the rope, to Thérèse, to the mine. His eyes widened. “Somebody’s down there?”

“Merde.”

“What’s going on?” More figures emerged over the top of the hill. A digger with a shovel, the incised scars in parallel lines down his cheeks marking him as a Far Northerner. A woman drenched in ocher muck from a panning pool, her braids piled high on her head. An elderly exchanger, stooped over and huffing, his hands bunching his silver robe around his thighs to keep the dust away.

“There’s a mine back here? Didn’t know that. Who owns it?”

“Everyone OK?”

“Somebody fall?”

Thérèse crouched over the edge of the hole and threw the rope down.

“ÉTIENNE!”

Silence. Just pebbles and grit vanishing into damp air carrying the odors of wet rock.

But it was the silence that finally broke her.

“What?” Still kneeling, Thérèse glared at the growing crowd. “No one brought honey wine to sip while they watch? Are you expecting me to give you some stew, so you can have a meal as you listen to my son die?”

Shuffling of feet. Averted gazes.

Thérèse lifted herself up. Pulling the bracelet from her dress, she shook it at the crowd. “Or is this the only thing you’re interested in?”

Eyes flickered to the gold, but no one moved, no one spoke.

“Cowards,” Thérèse said. “I curse my ancestors for planting their yams in the wretched village of Deng Deng.”

An explosion of mercury-white light cracked over the mine. Rushing air slammed against Thérèse. For a sickening moment, she thought she would fall forward into the dark void of the mine. But twisting, flailing her arms, leaning back, she managed to tumble backward. She landed hard on her hip and elbow.

“Curse our ancestors? Curse their names? Little reptile worm,” screamed ten mouths in unison. White Woman hovered above the mine, her hair pulsating with dark electricity. “We will crush this one like beetles in our teeth, like stones under a hammer. We will swallow her name into nothing!”

“So do it!” Thérèse winced as she stood up once more. Warmth trickled down her elbow, the joint on fire. A rock had broken the skin, she was sure. She also didn’t care. “Do anything.”

For a fraction of a heartbeat, a shard of White Woman’s silver glow solidified, solid as a looking glass. Thérèse’s reflection stared back at her. When had she become so dusty? Her dress lay in tatters, arm bleeding, her once-butter-smooth skin now mottled. But it was her eyes that changed the most. Fire glowed in them—something she hadn’t seen for a long, long time. And the flames were growing, spreading, consuming her from the inside out.

“I’ve served you all my life, and what have you ever done?” Thérèse pushed herself to yell, louder, harder. “Given me a dead husband, a dead son? Maybe two? What has my devotion brought me but misery?”

“We are—”

“Oh, shut up.”

The crowd gasped. The old exchanger turned and scurried down the hill. White Woman blinked. Thérèse almost stepped back. Almost. Just a lifting of her heel a millimeter or so. Then she stopped herself.

No more prayers, she thought. Not ever.

“I know what Dieudonné did. He took what was not his. He lied. He profited from the labor of others. His crime was against the village, against our traditions. And he suffered for it.”

“We are—”

“I’m not talking to you.” Thérèse angled herself to address the crowd. Northerners, Southerners, Coasters, exchangers, market women, diggers. Old and young, poor and poorer. They all stared back. Etched into their faces, she saw terror, hunger, desperation, long days digging in the unyielding earth and longer nights wondering how they would feed their families come morning.

She knew because all that was written on her face, too.

“I’m telling you that he stole to make his life better because the spirits wouldn’t. He prayed, he made sacrifices, and got nothing in return. All he wanted was to make his family happy. I know he broke our traditions. He took what he did not earn. He cheated. And he suffered for it. But my youngest did nothing.”

White Woman drifted to Thérèse. Her robin egg eyes glistened with rage. Her mouths leered. “We will suck your bones and make playthings of your skin.”

“No, you won’t. You won’t do anything.” Thérèse brandished the bracelet. “If someone stole the gold on the Moabi tree and you did nothing, why would you do anything now? Either you don’t care, or you can’t do anything. And you could have done something this entire time I’ve been talking. Call down the heavens. Summon wildfire to burn me up. You haven’t, because you can’t.” Thérèse held the bracelet to the crowd. “The spirits tell you they will help you find gold if you make sacrifices. But how many of you have found it? How many times has a spirit told you, ‘dig here, not there?’”

Thérèse hurled the bracelet into the mine. It winked once in the sun, once in White Woman’s fire, then it was gone.

“So, there’s your gold. Take it if you want. You don’t need a spirit to tell you where to find it anymore. Because I’m done praying and groveling for just a display of colors. The spirits of Deng Deng are broken.”

White Woman screamed. She raged, she howled, she twirled. Curtains of flame shot upward. Thérèse squeezed her eyes shut, the afterimage of the ten mouths screaming burned into her eyes.

“WE WILL NOT BE MOCKED!”

A hand slipped into Thérèse’s. Calloused. Thin. Hard. She squeezed and Sandrine squeezed back.

Then it was over. Thérèse opened her eyes. The mine stood there in the ground. The crowd huddled around it. The trees beyond the digging field still stood. The clouds passed overhead.

But White Woman was gone.

“Well?” Sandrine picked up the rope and shook it at the nearest digger. “You going to help, or you going to get out of the way?”

The miner looked at her, then at Thérèse. Thérèse stared back, breathing hard. Then the miner bent down to tug on the rope. “That knot’s going to slip. Let me.”

The crowd erupted into chatter.

“I think I have another rope at my shack.”

“Go get Bertine. She has those poultices.”

“Put some planks down there. Yeah, to reinforce the edge.”

Thérèse caught Sandrine’s eye. And for the first time in a long time, her lips twitched into a smile.

“Is this real?” Étienne whispered. “Is this here?” Or was it some trick of Death, some shared memory tantalizing him? Maybe just a product of fever.

Étienne tugged at the rope. It didn’t give. He yanked. The raffia fibers creaked.

Then from above, muffled and distorted, “Étienne!”

He felt a dozen snakes’ thoughts, all shared through the python, pound into his mind. People clustered together. Anticipation. White Woman and a storm of light. Then his mother, pointing and giving directions to men covered in mud. Encouragement. A rope.

Étienne squeezed his eyes against the barrage.

“No.” Death’s growl was the shattering of rocks in an earthquake. “You belong here. This is your path.”

“I’m down here!” Étienne’s voice echoed upward.

Here. Here. Here.

Silence, then a distant roar. The python flashed a dozen perspectives of people cheering, his mother sagging to her knees, a woman coming to her side.

Was that the Western woman? The images vanished before Étienne could decide.

Silence again, then a distorted voice. Étienne couldn’t make out the words.

The python interpreted. Rescue. Hold rope. They pull up.

Étienne clutched the rope. He tugged once, then leaned back. Its rough fibers bit into his palms. He rose.

Then his hand slipped. He winced as the rope chewed his skin, and he landed back on the ground. A drop of three or four centimeters at most.

The rope slackened as another incomprehensible shout came from above.

Knot. Make knot, said the snake.

“Stop,” said Death. “This isn’t fair.”

Clutching the rope with his left hand, Étienne tried to lift his right to the rope. Pain lanced through his forearm, like fire ants biting into the muscle. He grunted, tried to flex his fingers. White dots floated in his vision.

“Can’t,” he said through gritted teeth. “My arm.”

The python wound up Étienne’s legs and his chest. Hold rope.

Étienne clutched it. The snake slid over his left arm, then twisted over his hand and wrist. Étienne gasped. An unbidden memory of watching pythons coil over rats came to him. But he’d never imagined that the grip could be more like steel than flesh.

Reassurance. Basking on warm rocks. Comfort.

No slip. Me you knot. Now pull, brother, pull.

Étienne tugged. The slack went out of the rope, and he rose, slowly, centimeter by halting centimeter.

His shoulder screamed at the tension. He wondered if this arm, too, would break.

Death’s wail was a hurricane’s wind, the crash of trees under curtains of rain, swirling clouds pregnant with lightning.

“Stop them!”

The scorpion scuttled forward. Its pale glow reflected on the damp rocks.

The python hissed. Its resolution and self-preservation honed its thoughts to a point sharp as its fangs.

Crush. Grind. Kill.

“Kill him,” Death cried. “Now!”

A wave of exhaustion swept over Étienne. Kill, is that what the mob said as they beat Dieudonné?

The world had taken his brother. He wouldn’t add to its grief.

He stuck out his foot. His toe stopped short of the scorpion. “Come with us, if you like.”

The scorpion hesitated. Its tail flexed, curling and uncurling.

“I know somewhere nice and warm to sleep. Not this cold hole. There’s lots of nooks and crannies in my house. And crickets. I’ll make sure Maman leaves you alone.”

“Do it now!”

The scorpion crawled onto Étienne’s proffered foot. It held on with its scratchy legs as the rope jerked Étienne upward. A faint ring of light shone above, growing brighter.

“You belong with me!”

Étienne looked down. As if pressing against thin cloth, a face emerged from the darkness. A smooth head. Eyes shriveled into deep sockets. A nose pressed flat against low cheekbones. And a mouth, wide and cavernous, opening wider to swallow the world.

A hand rose from the void. Fingers sharp as thorns stretched for Étienne’s leg.

“With me!”

The scorpion whipped its tail and jabbed its stinger into Death’s thumb.

The hand vanished. The face contorted. Not in anger. Or rage. Or hate.

Sadness. Maybe loneliness. Étienne wasn’t sure because it melted back into nothing.

Light washed over Étienne. He heard weeping.

And cheering.

Hands seized his shoulders. Gravel scratched along his back and legs as he was dragged over the mine’s lip. He pried open his eyes to his mother burying her face into his chest, her sobs hot and wet. He took a breath, and his mouth flooded with the taste of her hair, the cool breeze from the forest, the aroma of dust.

“Maman?” he asked, still squinting against the brightness.

She squeezed him tighter. “Étienne, I—”

“Snake, there’s a snake!”

The python released its grip on his arm. Étienne looked up as the snake coiled on itself, head raised to face a man with a pickax. Scars covered his cheeks. A Far Northerner.

The man raised the curved steel above his head. The python hissed, opened its jaw.

“Don’t—” Étienne screamed.

The ax came down with a dull thud. Red droplets arched through the air, some splattering Étienne’s cheeks, lips, and flashing a sour saltiness on his tongue. A concussive blast of agony pushed through him. Étienne screamed, sharing the python’s fear, its pain, its death.

Then it was gone.

Étienne’s insides hollowed out. He slumped to the earth, his fingers digging into gravel.

His father to feed him. Dieudonné to make him smile. The snake to help him live.

All died because of him.

“You idiot!” A woman, tears welling in her eyes, rushed forward and wrenched the pickax from the miner. She flung it down the mine. A muffled clang of metal on stone replied.

“What?” The man turned, mouth opening as he took in the shocked stares, the muttered curses. He shrugged. “It was just a snake.”

“Scorpion,” someone yelped. The crowd shuffled and squirmed. Snakes were one thing. This was Deng Deng, the village of the Children of Beti, the brothers of snakes. Spend enough time at Deng Deng and one would get used to being around serpents.

Scorpions were different. Scorpions had only one master.

Étienne rolled to his side to see feet leaping away from the scorpion. The creature scuttled over rocks, its shell black and shiny as polished glass. A sandaled foot landed to its left. The scorpion darted right. A shovel slammed down on the rock where it had been a moment ago. Another foot rose.

Ignoring the pain, Étienne flung himself over the scorpion. The foot landed on his thigh. He grunted and curled himself around the creature.

“She’s my friend,” he shouted. “Don’t hurt her. Don’t hurt her.”

The shuffling stopped. Étienne waited a moment then wormed his hand under his chest. The scorpion wriggled against his palm. Alive. Frightened, but alive.

Étienne sat. The scorpion scuttled into the crevices of his clothing. People eyed them and took a step back.

Étienne started to crawl to the body of the python, but his mother swept him up in her arms. She pulled him to her chest, blocking the world from view. She wept, rocking him.

“I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry,” she said. “I didn’t mean it. I didn’t mean it.”

Étienne’s sobs joined hers as their tears mingled on his cheeks.

Night

Part of him—more than a part, most of him—wished he were still in the mine.

His thoughts returned again and again to the pickax slamming into the python, the sandal almost squishing the scorpion, the flames dancing along his brother’s body. His fault, all of it.

He didn’t deserve to be saved.

The window above Étienne’s cot cut the moonlight into a square that stretched across the floor. It flashed pink as a spirit flew past, then returned to its pale silver. A whoop drifted from the village center, where the last revelers still guzzled bottles of honey wine or beer.

He twisted to face the wall.

Étienne scratched an itch at the edge of the still-damp plaster entombing his right arm. It had barely been applied when White Woman came to their house, a dozen spirits trailing behind her, their glows pulsating like a discordant rainbow. His mother, her face a mask, had gone to greet them.

“Why are they here?” Étienne asked the Westerner—Sandrine, he had learned. He sat on the floor, sucking on bitter herbs to temper his fever.

As Sandrine opened her mouth to reply, White Woman spun in a circle, her hair sending out sparks of white flame.

“A feast, my feast, we will bring a feast. We give him to her, this little lost snakeling, we bring him to our beloved daughter. Make a feast, a feast for our goodness.”

Étienne could only stare as his mother gave her thanks to the spirits for Étienne’s safe return and her gratitude for their generosity.

But she didn’t bow.

It was later that night that as they sat near the Moabi tree that Sandrine answered his question.

A slaughtered goat roasted over coals while marmites of fish stew, rice, and kelen-kelen soup piled high. Bottles of wine and beer passed from hand to hand. Spirits, more than Étienne had ever seen in one place, mingled with the villagers of Deng Deng. White Woman danced, singing with her many mouths, while other spirits answered with strained melodies from the trees.

Sandrine, her eyes glassy from honey wine, leaned in and whispered, “They’re afraid. Of you and your maman.”

Étienne looked up.

“Your mother called the spirits broken. I don’t think that’s right. They’re starving ’cause Deng Deng has too much greed, too much pollution, not enough hope to go around. So, the spirits are pretending like today never happened. Or like it was all just some great lesson.”

“What lesson?”