In early 1965, due to the South Vietnamese government’s political and military instability, American President Lyndon Johnson ordered a US Marine Light Anti-aircraft Missile (LAAM) Battalion of 500 men to the Republic of Vietnam (RVN). The worry was fear of an aerial attack by North Vietnamese aircraft. The men and equipment of the Marine LAAM were in place around Da Nang airfield in northern South Vietnam by 16 February 1965.

In late February 1965, President Johnson decided to commit major ground combat forces of the United States armed forces to secure portions of South Vietnam, referred to as ‘enclaves’. The aim was to help stabilize the government of South Vietnam and its military forces. The initial choice would be either a US Army airborne brigade or a Marine Expeditionary Brigade (MEB).

As an MEB contained the organic logistic element and the US Army airborne brigade did not, the decision was to deploy the Marine unit. Between 8 and 9 March 1965, elements of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade (MEB) arrived in South Vietnam unopposed except for minor sniper fire. They came in by sea and air near the coastal city of Da Nang. Their assigned role was the protection of the Da Nang air base and the already-in-place Marine LAAM in an area encompassing roughly 8 square miles.

The men of the LAAM and the 9th MEB would not be the first Marines in South Vietnam. A single Marine officer had arrived in South Vietnam in 1954 as a liaison to the newly-established United States Military Assistance and Advisory Group (MAAG) to the Republic of Vietnam.

By 1964, the number of Marines in South Vietnam had risen to almost 800 men; most were military advisors. However, included in that number were the personnel of a single Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron (HMM, Helicopter Medium Marine). They had arrived at the Da Nang air base in September 1962 to support the Republic of Vietnam Army, hereafter referred to as the ‘ARVN’. In contrast, the US Army had approximately 20,000 advisors in South Vietnam by 1964.

The initial Marine troop contingent of the 9th MEB that arrived at Da Nang consisted of approximately 5,000 men, divided into two infantry battalions and two helicopter squadrons. By the end of April 1965, the 9th MEB had around 9,000 men in South Vietnam. Usually in support of an MEB is a single Marine Aircraft Group (MAG). The 9th MEB, however, had two MAGs in support as of March 1965. These consisted of only fixed-wing assets.

The 9th MEB that arrived in South Vietnam in March 1965 came from the ranks of the 3d Marine Division. On paper, an MEB is usually organized to accomplish only limited missions and is typically commanded by a brigadier general. When and if that mission finishes, an MEB is reabsorbed by the next higher command level, the division.

While an MEF (Marine Expeditionary Force), the command level above a Marine division, typically oversees only a single reinforced division, it may when required manage two. The MEF is commanded by a major general or a lieutenant general, depending on its size and mission. It can be configured for different types of combat in a wide variety of geographic areas. The aviation combat element of an MEF is a Marine Aircraft Wing (MAW).

On 5 May 1965, Marine leadership decided in light of increasing deployment to organize all ashore as the III (3d) MEF. Two days later it would be relabelled the III Marine Amphibious Force (MAF). Its command went to two-star Major General Lewis W. Walt. By the end of 1965, the III MAF consisted of over 45,000 personnel.

Besides infantry battalions, the III MAF had by the end of 1965 eight fixed-wing squadrons, eight helicopter squadrons and a reinforced artillery regiment. In addition, it had under its control sixty-five medium tanks, twelve flame-thrower tanks, sixty-five tracked anti-tank vehicles and 157 machine-gun-armed amphibious tractors. There were also six amphibious tractors, each armed with a turret-mounted 105mm howitzer.

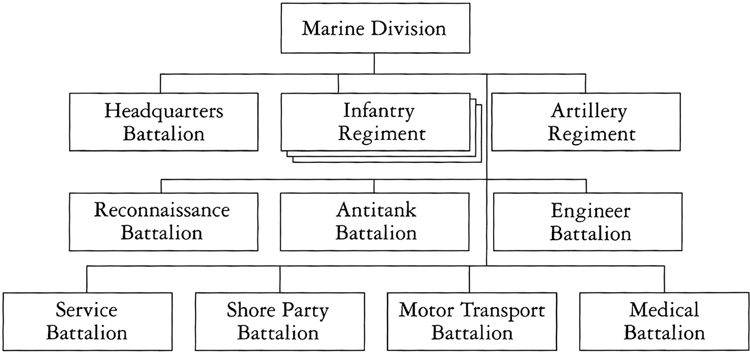

At the time of the Marine Corps initial large-scale commitment to the Vietnam War in 1965, the approximately 20,000-man division remained the basic building block of its combined arms ground organization. Its primary purpose was to perform amphibious assault operations as had occurred during the Second World War.

Marine divisions were also organized to execute sustained land campaigns when appropriately reinforced. Reinforcements consisted of combat support and combat service support elements. Aviation support elements were assigned depending on mission requirements, to operate from US Navy aircraft carriers until such time as air bases could be established ashore.

Reflecting the nature of the terrain and opponents faced by the Marines, divisionsized ground operations were not required. Instead, infantry battalions or even companies were the key manoeuvre elements. The infantry battalions themselves were often randomly assigned to other infantry regiments for operations rather than serving under their parent infantry regimental commands.

In some cases, infantry battalions would be under the operational control or ‘opcon’ of a mission-specific task force headquarters. Infantry companies were also sometimes mixed and matched during operations. One Marine general reacted favourably to this practice as it ‘. . . gave the division commander great flexibility’. However, it was felt that such flexibility came at a price: ‘Command lines were somewhat blurred and tactical integrity was more difficult to maintain.’

In 1951 the Marines dispensed with the command label of corps and substituted the name ‘Force Troops’. That command organization served under the Fleet Marine Force (FMF), which corresponded to a US Army Field Army. The Force Troops of the FMF oversaw units ranging in size from regimental level to individual teams composed of only a few men. The general commanding an FMF was responsible for selecting and attaching Force Troop assets to divisions based on requirements.

Beside the combat elements of the Force Troops, such as tanks, heavy artillery and amphibious tractors, there were other equally essential units. These included a Force Service Regiment to provide Marine divisions in a combat theatre with additional logistical support. To supplement a Marine division’s organic truck element, Force Troops could provide 126 trucks from a motor transport battalion.

To complement the divisional engineer elements of Marine divisions, Force Troops could contribute an engineer battalion. The engineer elements of Marine divisions tended to construct temporary works, while those of the Force Troops were responsible for projects of a more permanent nature, such as airfields, utility systems and bridges. In addition, they performed demolition services and could also operate ferries to transport men and equipment across inland waterways.

The fighting core of Marine divisions in 1965 was their three infantry regiments, each consisting of around 3,500 men commanded by a colonel. The triangular regimental arrangement originated with the formation of the first two Marine divisions in 1940, also adopted by the US Army for its infantry divisions in the same time frame.

Early combat experience during the Vietnam War demonstrated that the Marine division’s three infantry regiments provided insufficient manpower for the tasks assigned. This led to reinforcing each division with a fourth infantry regiment by 1967. Upon their departure from South Vietnam, the two Marine divisions that served in Vietnam reverted to their original three-infantry regiment structure.

Marine infantry regiments in 1965 had three infantry battalions, with approximately 1,110 men each. A division, therefore, had an authorized strength of nine infantry battalions totalling around 10,000 infantrymen. The infantry battalions also included a headquarters and service (logistical) company and a weapons company. The latter contained an 81mm mortar platoon, and an anti-tank platoon equipped with ground-mounted and wheeled vehicle-mounted 106mm recoilless rifles.

Each Marine infantry battalion consisted of four infantry companies of 216 men, commanded by a headquarters section of 329 men overseen by a captain. The headquarters section directed the actions of three rifle platoons of forty-seven men each and a single weapons platoon of sixty-six men. The latter had in its inventory 3.5in rocket-launchers, eventually replaced by the Light Anti-tank Weapon (LAW), flamethrowers and 60mm mortars. A lieutenant commanded each platoon.

The rifle platoons were further divided into three rifle squads of twelve men, overseen by sergeants. The rifle squads in turn consisted of three fire teams, four-man manoeuvre elements directed by corporals. Armament for the rifle squads in 1965 consisted of the M14 rifle, the M60 machine gun and the M79 Grenade-Launcher. The M14 rifle was replaced in Marine infantry units in early 1967 by the M16 rifle and later by the improved M16A1 rifle.

A critical force multiplier in the Marine divisions of 1965 was a single artillery regiment. Each Marine division artillery regiment of 2,757 men had a headquarters battery that coordinated the actions of its four artillery battalions.

Three of the four artillery battalions in a regimental artillery regiment were equipped with the towed M101A1 105mm howitzer and a single battery of the M30 107mm mortar. These formations were labelled ‘direct support’ battalions. The remaining artillery battalion had towed M114A1 155mm howitzers and was designated the ‘general support’ battalion.

In 1965, the Marines’ artillery regiments in South Vietnam began replacing some of their towed 155mm howitzers with the new M109 self-propelled vehicle armed with a 155mm howitzer. However, due to the M109’s size and weight, it could not be airlifted by helicopter. This left a requirement for the older 155mm towed howitzer that could be airlifted.

Typically, each of the three 105mm howitzer battalions of an artillery regiment was under the tactical control of one of the division’s three infantry regiments. The single 155mm battalion (towed or self-propelled) usually remained under the tactical control of the division’s artillery regiment. However, for specific operations, it too could be placed under a Marine infantry regiment’s tactical control.

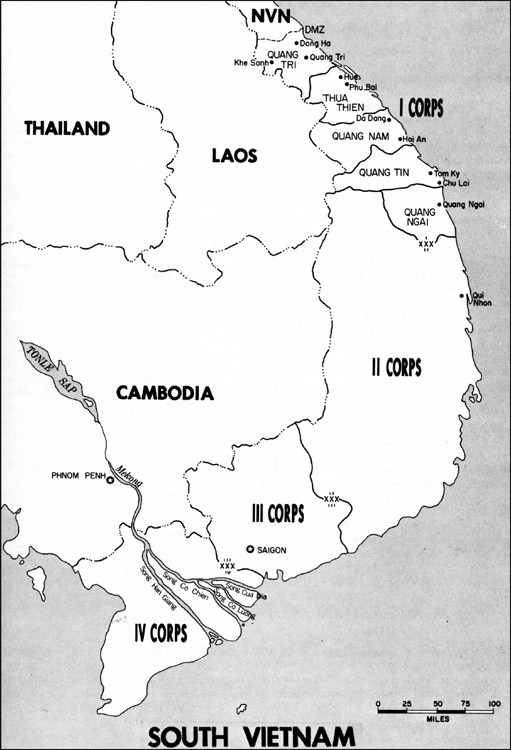

During its time in South Vietnam, the III MAF was responsible for the security of what the US Army designated the I Corps Tactical Zone. During the Vietnam War there existed four corps tactical zones, with the II and III Zones overseen by the US Army. The IV zone was the sole responsibility of the ARVN as there were few US Army units in that area until 1967.

The I Corps Tactical Zone (hereafter referred to as I Corps) included South Vietnam’s five northernmost provinces, encompassing a landmass of approximately 10,000 square miles ranging from rice paddies to steep, tropical jungle-covered mountains. I Corps’ northernmost boundary was the demarcation line between North and South Vietnam, typically referred to as the ‘Demilitarized Zone’ (DMZ).

An estimated 2.6 million people lived within I Corps in 1965. Most lived in rural communities in the coastal regions. The other thirty-nine South Vietnamese provinces south of I Corps had an estimated population of 16.5 million people, including extensive rural areas and the large urban centre of Saigon, then the capital of South Vietnam.

The III MAF shared the responsibility of I Corps with two ARVN divisions stationed within the same area. Both the Marine and US Army units in South Vietnam were considered guests of the ARVN and did not have command authority over them; hence in theory they had to clear their plans with the local ARVN commanders before conducting any operations.

On 10 April 1965, a Marine Landing Team (MLT) arrived at Phu Bai, South Vietnam, located within 7 miles of the ancient Vietnamese Imperial capital of Hue. The MLT was to establish a base for guarding the surrounding area as well as those charged with building a new military air base on site. A secondary responsibility would be protecting a nearby US Army communication unit. Phu Bai eventually became home to the headquarters of the 3d Marine Division.

In late April 1965, a high-level decision came about for the deployment of an additional 5,000 Marines from the 3d MEB, consisting of elements of the 3d Marine Division. Rather than reinforcing the troops already based around Da Nang or Phu Bai, these units were sent to set up another enclave near the South Vietnamese coastal city of Chu Lai, located 57 miles south of the Da Nang air base. Marine engineers were building another airfield that would relieve some of the overcrowding at the very busy Da Nang air base.

The 3d MEB’s deployment at Chu Lai beginning on 7 May and running through to 12 May 1965 was unopposed. The engineers had the air base up and running by 1 June 1965. Chu Lai eventually became home to the headquarters of the 1st Marine Division.

With the 3d MEB’s arrival, the bulk of the 3d Marine Division was in place. It was at this point in June of 1965 that both the 3d and 9th MEBs were deactivated and reverted to their parent command, the 3d Marine Division.

In June 1965, a single Marine rifle battalion was assigned to form another protective enclave around a US Army logistical base and airfield at the coastal city of Qui Nho’n. The city lay 188 miles south of the Da Nang air base.

The role of the 9th MEB at the Da Nang air base remained strictly defensive until 1 April 1965, when President Johnson authorized them to go on limited offensive patrols. The first began on 20 April 1965. Two days later a small patrol composed of Marines and an AVRN unit encountered an enemy force, with one Viet Cong (VC) killed and a single Marine wounded in the ensuing engagement.

There would be other battles between the VC and the Marines between March and June 1965. In these fights the Marines lost 34 killed and 134 wounded. VC losses were 270 killed. With enough troops and equipment in place and with the formation of the III MAF, the Marine leadership was approved to mount larger offensive operations beginning in July 1965.

In July 1965, the III MAF commander in a written directive to his men stressed ‘. . . the indiscriminate or unnecessary use of weapons is counterproductive. The injury or killing of hapless civilians inevitably contributes to the Communist cause, and each incident of it will be used against us with telling effect.’

Enemy Terms

A literal translation of ‘Viet Cong’ is ‘Vietnamese Communist’. The official name of the Viet Cong, or VC for short, was the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NFLSVN). Despite trying to portray itself as an ingenuous South Vietnamese-led force, it was always directed by the North Vietnamese communist leadership of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV). The DRV’s military arm was the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN), or the North Vietnamese Army (NVA).

From a US military pamphlet comes a description of the two types of VC personnel encountered by American military forces: ‘The Viet Cong’s full military element also is divided into two types: the Regional Forces and the Main Force . . . The elite units of the so-called Liberation Army are the battalions of the Main Forces.’ They typically did not have the most modern weapons and equipment employed by the NVA.

In spite of more offensively-orientated Marine patrols, the VC mounted a successful hit-and-run attack on the massive Da Nang air base at midnight on 1 July 1965. It consisted of an eighty-five-man enemy unit armed with mortars, machine guns and demolition charges. Destroying three aircraft and damaging two more, they escaped with only one casualty, a member captured by an ARVN unit.

On the evenings of 27 and 28 October 1965, the enemy successfully attacked two Marine airfields: a helicopter facility located on the Tien Sha Peninsula and the Chu Lai air base. Colonel Leslie E. Brown, who was at Chu Lai when it was attacked, remembered the first thing that he and the other Marines present knew of the enemy attack: the sound of machine-gun fire and demolition charges going off. He would recall:

. . . a couple of the airplanes were on fire, and the sappers [demolition experts] had gotten through intact . . . they were barefooted and had on a loincloth, and it was kind of a John Wayne dramatic effect. They had Thompson submachine guns, and they were spraying the airplanes with the Tommy guns and . . . throwing satchel charges into [aircraft] tailpipes . . . Some went off and some didn’t, but the net effect was that the machine-gun fire caused leaks in the fuel tanks, so the JP fuel was drenching the whole area. . .and in the middle of that, the airplanes were on fire.

Of the twenty VC who attacked the Chu Lai air base, the Marines killed fifteen for the loss of two planes destroyed and severe damage to six more. The enemy attack on the Marine helicopter base on the Tien Sha Peninsula consisted of ninety men divided into four separate demolition teams. Under cover of mortar fire, they managed to destroy nineteen helicopters and damage another thirty-five, as well as damage a new hospital under construction. The attackers lost seventeen dead and four wounded. The Marines had three killed and ninety-one wounded.

From the Marine Corps Historical Branch monograph titled Marines and Helicopters 1962–1963 by Lieutenant Colonel William R. Fails comes the following passage on the enemy attack on the Marine Tien Sha Peninsula helicopter base:

Three and possibly four teams conducted the assault. One unit attempted to breach the defenses near the H&MS [Headquarters and Maintenance Squadron] hangar. There they met Mortimer, O’Shannon and Brule. ‘We’d been in the hole only about 20 seconds when we saw about eight people, all armed, running towards us,’ said O’Shannon. ‘They were about 30 to 40 feet away. We saw they were Viet Cong. When they got within 15 feet of us, we opened fire with our rifles.’ Their Marine Corps training paid off well. All three happened to be ‘expert’ riflemen and annihilated the enemy squad, killing seven and wounding and capturing four others.

A planned enemy attack on the air base at Da Nang, to have been conducted on the evening of 28 October, might have been foiled by a couple of occurrences. First, the III MAF received information the day before of an approaching VC main force battalion 10 miles south of the air base. In response, an artillery barrage was directed into the area they were thought to be. By default, this alerted the enemy to the fact that a surprise attack on the Da Nang air base would now be out of the question.

A Marine infantry squad ambushed a strong VC main force 5 miles south of the Da Nang air base on the night of 28 October. Realizing that they were significantly outnumbered, the Marines withdrew under a protective screen of 81mm mortar fire. Before retiring, they counted fifteen dead enemy soldiers in front of their position as the enemy forces disengaged from the ambush.

On 30 October 1965, the VC attempted to capture a company-sized Marine Corps defensive position labelled Hill 22. It lay south of Da Nang air base next to the Tuy Loan River. The attack began when ten to fifteen enemy soldiers walked into a Marine ambush. Despite losing the element of surprise, the VC pressed the attack two hours later in much larger numbers and managed to capture a portion of the Marine position before being driven off. They suffered forty-seven dead and one wounded. Marine casualties were sixteen killed and forty-one wounded.

In early August 1965, the III MAF became aware of an approximately 1,500-man VC main force regiment located on the Phuoc Thuan Peninsula. The enemy-occupied peninsula lay just 12 miles south of the Marine enclave of Chu Lai, the anticipated goal of the enemy regiment.

Rather than wait for the enemy to attack first, the III MAF quickly arranged for a two-infantry battalion force to deploy near the VC-occupied area beginning on 17 August. The Marines came by sea and air in what became known as Operation STARLITE.

Initially, the Marines faced minimal resistance and losses as they advanced towards the expected location of the enemy regiment on 18 August. That soon changed, and they encountered strong opposition from the combat-experienced VC regiment. One airlifted Marine rifle company was unknowingly deposited directly on top of an emplaced VC battalion, leading to fierce fighting and damage to numerous Marine helicopters.

The fierceness of the fighting on 18 August appears in the awarding of Medals of Honor to two Marines fighting in Operation STARLITE. Corporal Robert Emmett O’Malley earned one of these when his squad came under heavy fire from a dug-in enemy unit. Rather than seek cover, according to his Medal of Honor citation, he: ‘. . . raced across an open rice paddy to a trench line where the enemy forces were located. Jumping into the trench, he attacked the Viet Cong with his rifle and grenades, and singly killed 8 of the enemy.’

O’Malley’s daring exploits continued throughout the remainder of the 18 August engagement. From his citation: ‘Although three times wounded in the encounter, and facing imminent death from a fanatic and determined enemy, he steadfastly refused evacuation and continued to cover his squad’s boarding of the helicopters while, from an exposed position, he delivered fire against the enemy until his wounded men were evacuated.’

Other Marine ground units began encountering stiff enemy resistance on 18 August, despite strong support from F-4 Phantoms and A-4 Skyhawks of five different Marine squadrons. The squadrons flew seventy-eight sorties (missions) on 18 August and in the process dropped 65 tons of bombs, 4 tons of napalm and fired hundreds of 2.75in rockets and thousands of rounds of 20mm ammunition.

Then Colonel Leslie E. Brown, a Marine officer during Operation STARLITE, stated in a 14 August 1975 interview conducted by the Marine Historical Center:

The Marines were in trouble . . . and our airplanes were literally just staying in the flight pattern, and they’d land and re-arm and take off, be right back again in a few minutes just dropping and strafing and firing rockets . . . in the three-day period, we flew more sorties than in the history of any other attack group before or since in support of that one operation which took place . . . in an area probably about 2 miles square.

In addition to aerial support, the Marines on the ground had both Marine artillery support as well as fire support from three US Navy warships. On 19 August a group of around 100 enemy personnel was observed on a beach by a US Navy destroyer in what appeared to be an attempt to escape. They found themselves engaged by the destroyer’s 5in guns, which caused them severe losses. The ship also sank seven sampans that the enemy had obtained as part of their aborted escape attempt.

Owing to the immense firepower advantage enjoyed by the Marines, including tanks, the remaining elements of the VC regiment trapped on the Phuoc Thuan Peninsula slipped through the Marine cordon on the night of 18 August. There remained left behind enemy elements that had to be subdued, one by one, extending Operation STARLITE through to 24 August.

At the conclusion of Operation STARLITE, the Marines counted 614 enemy soldiers killed on the battlefield, with 9 taken prisoner and another 42 enemy suspects taken into custody. Marine losses were 45 dead and 203 wounded. A Marine regimental commander involved in Operation STARLITE had this to say about the tanks they had in support: ‘The tanks were certainly the difference between extremely heavy casualties and the number we actually took. Every place the tanks went, they drew a crowd of VC.’

The Marines were proud of the outcome of their first major battle with the enemy. However, they also learned that VC main force units were a formidable foe and had to be respected. ARVN generals were not impressed with the destruction of the VC main force regiment, as they had seen VC units quickly re-formed and on the battlefield months later.

To finish off the enemy regiment engaged during Operation STARLITE, the III MAF mounted a number of operations in cooperation with ARVN forces from September through to November 1965 without much success, as the VC regiment refused to enter into combat with them. In early November 1965, the VC commenced attacks against the weaker ARVN forces.

Despite Marine aerial support and ARVN replacements, on the morning of 10 December the VC regiment attacked once again and overran one of the ARVN regiment’s two battalions. At this point, on 10 December, the III MAF committed two Marine infantry battalions to the fight.

Once engaged in the battle, the Marines also suffered substantial casualties at the hands of the VC regiment. Additional Marines were therefore committed to the fight on 11 December, but the enemy had already disengaged from the battle and successfully withdrew.

The Marines decided to track down the VC regiment and engage it in battle, which they managed to do on 18 December at a location known as Ky Phu. Confronted by Marine artillery fire and aerial support, the enemy quickly realized that the odds were against them and attempted to withdraw. First Lieutenant Nicholas H. Grosz, who had accompanied one of the Marine infantry companies on the operation, stated: ‘Once we got them going, the VC just broke and ran. It was just like a turkey shoot.’

By the time the engagement between the Marines and the enemy regiment concluded on 20 December, the Marine and ARVN combined operation had claimed 407 enemy troops killed and thirty-three captured, with many weapons and supplies seized. Marine losses came to forty-five killed and ninety wounded. ARVN losses were reported as ninety killed, ninety-one missing and 141 wounded.

A significant contributing factor to the Marine success during its initial battles with the main force VC lay with the support from various Marine helicopter units. Flying more than 9,230 sorties, these units carried approximately 12,117 troops and transported over 600 tons of supplies. Marine UH-1E helicopter gunships, armed with machine guns and rockets, provided close air support when Marine jets could not carry out their missions due to poor visibility.

Besides moving infantry around the battlefield, Marine helicopters also performed many other vital roles including reconnaissance and medical evacuation. The enemy attempted to shoot down Marine helicopters on more than a hundred occasions during the operation. A total of fifty-three helicopters were damaged, but only two destroyed. Personnel losses among the helicopter crews proved to be only one killed and twelve wounded.

During the last half of 1965, the III MAF had conducted fifteen operations consisting of battalions or larger units. Essential lessons on what had and hadn’t worked came out of these various operations. However, despite these numerous operations, on 10 December 1965 General Westmoreland stressed in a letter to all his subordinate commanders that more aggressive operations were required on their part against main force VC formations for the US forces in Vietnam to stand a chance of success. The commander of the III MAF had anticipated this development, and had in the summer of 1965 informed his superiors that more Marines would be required.

Former Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, seen here, took presidential office following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on 22 November 1963. Johnson entered into office having to deal with the faltering government of South Vietnam and its military. He was, however, convinced that with American military assistance the South Vietnamese could prevail over the Viet Cong. (DOD)

The first Marine Corps formation to arrive in South Vietnam in 1965 was a Light Anti-Aircraft Missile (LAAM) Battalion on 8 February. The unit’s armament consisted of the Hawk anti-aircraft missile system pictured here on its launching unit. The radar-guided missile had an effective slant range of 15 miles and a maximum effective ceiling of 65,000ft. (USMC)

The Hawk was 12ft 6in in length, with a diameter of 14in and a wingspan of about 4ft. It weighed 1,295lb and contained a 120lb warhead with contact and radio-based proximity fuses. In support of the LAAM Battalion, a company of Marine engineers landed by sea near Da Nang air base on 17 February 1965. (USMC)

On 8 March 1965, elements of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade (MEB) landed near the Da Nang air base. Included among the equipment they brought were the M48A3 medium tanks seen here on board a US Navy landing craft. The diesel-engine-powered A3 version of the M48 series had entered Marine Corps service in late 1964. (USMC)

Elements of the 9th MEB were also airlifted into Da Nang air base from Okinawa on 8 March 1965, in US Air Force (USAF) transport aircraft. Unlike those elements of the 9th MEB that had come by sea, those that came by aircraft were subjected to sporadic ground fire that fortunately scored no hits. (USMC)

Prior to the Marine Helicopter Transport Squadron Light HMR(L)’s arrival in South Vietnam in 1962, Marine Corps advisers had been in the country since 1954. Pictured here is one of the advisers pointing out the various features of a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) to a South Vietnamese Marine. Besides advising the South Vietnamese Marine Corps, the US Marine advisers did the same for some ARVN units. (USMC)

The Marines of the 9th MEB were not the first deployed to South Vietnam. A Marine Helicopter Transport Squadron Light HMR(L) had previously been deployed in South Vietnam in April 1962 to aid the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). They flew the Sikorsky UH-34 pictured here. Originally designated the ‘HUS-1’, the UH-34 had entered Marine Corps service in 1957. (USMC)

On arriving in South Vietnam, the men of the 9th MEB found themselves restricted to only being observers. The American Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) forbade them in a 7 March 1965 directive that stated: ‘US Marine Force will not, repeat, will not, engage in day-to-day actions against the Viet Cong.’ Guarding the Da Nang air base remained the responsibility of the ARVN. (USMC)

Marines are shown here coming ashore in South Vietnam. Before the arrival of the 9th MEB there were on 28 February 1965 a total of 1,248 Marines in and around the Da Nang air base. These included a security company of 260 men assigned to guard the Marine Helicopter Transport Squadron Light HMR(L) based at Da Nang. (USMC)

By 23 March 1965, with the arrival of the 9th MEB, there were 4,612 men in and around the Da Nang air base. Of that number, 583 belonged to a Brigade Logistic Support Group. Unfortunately, the Marine logistic system intended to support the 9th MEB quickly broke down, resulting in serious shortages of everything from rations to artillery ammunition. (USMC)

It would not be for lack of trying that the Marine logistical system in South Vietnam failed early on. The Marine Corps had a then state-of-the-art computerized supply system. However, once in the country, the computer stock cards (punch cards), according to a report, ‘began swelling due to the high humidity and the cards wouldn’t fit in the machine [computer].’ Everything, therefore, had to be done manually. (USMC)

Adding to the Marine Corps’ logistical support problems was the lack of adequate unloading facilities at the port of Da Nang, causing supply ships to remain in Da Nang harbour for two weeks or longer before having a chance to unload their cargos. Pictured here are cargo ships docked at the port of Da Nang. (US Navy)

As there was no suitable highway infrastructure in South Vietnam to handle the amount of truck traffic required to support Marine units, heavy engineering equipment such as the compactor pictured here was employed in building roads from dawn to dusk, seven days a week. Mechanics had to work every night to have the equipment ready for the next day. (USMC)

Pictured here is a Marine armed with an M14 rifle in South Vietnam. The M14 had a twenty-round box magazine that inserted into the bottom of its receiver. As of 20 April 1965, the 9th MEB in South Vietnam consisted of 8,607 men with the majority stationed around the Da Nang air base. On that same day, they gained permission to engage in aggressive patrolling. (USMC)

On 22 April 1965, the Marines of the 9th MEB had their first encounter with the Viet Cong, losing one man and claiming one enemy soldier killed. On 29 April 1965, the Marines participated in their first combined operation with the ARVN. Searching a village for any signs of the Viet Cong, such as weapons or ammo, is a Marine in the foreground with an M14 rifle and an ARVN soldier equipped with an M1 Garand. (USMC)

The M14 rifle seen here in the hands of a Marine in South Vietnam proved somewhat unsuitable in theatre for a variety of reasons. These included its inability to be fired accurately in fully-automatic mode, reliability issues and parts breaking. Its weight and size also caused issues in the often close confines of the country’s terrain. (USMC)

On 20 April 1965, President Johnson committed a Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF) to Da Nang. The initial elements of the III MEF arrived at Da Nang on 3 May 1965. Pictured here are Marine engineers constructing steel matting for a boat ramp. On 7 May 1965, the III MEF became the Marine Amphibious Force (MAF). (USMC)

As of 30 May 1965, there were approximately 17,000 Marines in South Vietnam, with the largest number (9,224) operating out of the Da Nang air base. Another 6,599 were at Chu Lai. On 4 June 1965, three-star Major General Lewis W. Walt took command of the III MEF, which included all Marine Corps personnel within I Corps. In this post-Vietnam War photograph, we see him as a four-star general. (USMC)

Founded in October 1955, South Vietnam consisted of forty-four provinces of varying size and population. Militarily it was divided into four corps zones numbered one to four (as seen in this map). The III MAF was assigned the security of the five northernmost provinces of the country, which fell within the I Corps’ region of responsibility. (USMC)

In this map of the five northernmost provinces, the III MAF’s zone of responsibility, lay Da Nang, the home of the largest and most important Marine Corps base in the country from 1965 until 1971. The border that divided North Vietnam and South Vietnam was referred to as the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) by the American military and also appears on the map. (USMC)

The III MAF had as its organic air support the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing (MAW). The 1st MAW had a personnel strength of approximately 13,000 men and was subdivided into Marine Aircraft Groups (MAGs), including both fixed-wing and helicopter squadrons. Pictured here is a Marine A-4 Skyhawk, a single-seat light-attack bomber. (USMC)

The primary purpose of the fixed-wing MAGs was the support of Marine Corps ground formations. They also provided armed escorts to Marine helicopter formations. Pictured here is an F-8 Crusader, a type that first entered into Marine Corps’ service in 1956. Originally intended as an interceptor, it saw useful service as a close-support aircraft during the Vietnam War. (USMC)

The biggest issue facing the 1st MAW was who would oversee its actions. The Marines felt that the USAF had not effectively employed Marine air assets during the Korean War (1950–53) and did not want to repeat that arrangement in Vietnam. The Marine Corps’ leadership, however, was overruled and certain fixed-wing Marine squadrons fell under USAF command beginning in 1965. Shown here is an F-8 Crusader. (USMC)

Two basic types of ‘close air support’ missions took place during the Vietnam War. One received the name ‘pre-planned’. Requests for such had to be placed twenty hours ahead by ground commanders. That request would pass to the Direct Air Support Center (DASC) and the Tactical Air Direction Center (TADC) for approval and coordination. Pictured here during a close-support mission is an F-8 Crusader. (USMC)

Another type of close air support mission flown by the 1st MAW during the Vietnam War bore the name ‘on-call’. Its title is self-explanatory and could be made in emergencies by aircraft already in the air intended for such missions, or by diverting aircraft from other missions. The F-4 Phantom II pictured here was the eventual replacement for the F-8 Crusader in South Vietnam. (USMC)

Ground crewmen are loading 20mm ammunition into a Marine F-8 Crusader. Another type of mission performed by the 1st MAW bore the name ‘direct air support’. In this case, aircraft would not operate in support of ground formation. Rather, they performed missions directed at isolating the enemy from the battlefield and destroying their support bases. (USMC)

To avoid friendly-fire incidents by Marine fixed-wing aircraft supporting ground formations, Marine tactical air coordinators (TACs) provided oversight. Several modified aircraft types were employed by the TACs. One such was the two-seat TF-9J Cougar trainer aircraft pictured here. Other TAC platforms included a light propeller-driven aircraft or a helicopter gunship. (USMC)

The 1967 replacement for the two-seat TF-9J Cougar in the TAC role would be the two-seat trainer TA-4F Skyhawk shown here. Like its predecessor, the TA-4F Skyhawk had wing-mounted rocket pods for marking targets for the weapon-carrying jet aircraft. The TACs maintained contact with ground units via FM radios while directing attack aircraft with UAF radios. (USMC)

On occasion, the fixed-wing ground-based squadrons of the 1st MAW also crossed into North Vietnam to suppress enemy anti-aircraft defences during rescue missions for the pilots and air-crew of downed USAF aircraft. Other Marine fixed-wing squadrons flying off aircraft carriers flew attack missions all over South Vietnam and North Vietnam. Pictured here is a Marine F-4 Phantom II. (USMC)

When venturing over North Vietnam, the fixed-wing jet aircraft of the 1st MAW found themselves subjected to a wide range of Soviet-designed anti-aircraft guns. One of these, seen here, was the S-60, a towed short-to-medium-range single-barrel 57mm anti-aircraft gun. Besides an on-carriage optical fire-control system, it could also be controlled by an off-carriage radar-directed fire-control system. (Vladimir Yakubov)

To protect Marine aircraft (as well as other friendly planes) over North Vietnam and Laos, there would be the EF-10B Skynight pictured here that served until 1969 as electronic warfare (EW) aircraft. It identified enemy radar systems in the electronic intelligence (ELINT) role and then jammed them in the electronic countermeasure (ECM) role. (USMC)

The most important military sites in North Vietnam were protected by the Soviet-designed and built radar-guided SA-2 Guideline anti-aircraft missile system pictured here. Introduced into Soviet Army service in 1959, it would be supplied to the North Vietnamese military beginning in 1965. The missile had a slant range of up to 31 miles and a maximum altitude of 82,000ft. (Vladimir Yakubov)

Photo reconnaissance missions over both South and North Vietnam as well as Laos were performed by the RF-8A pictured here, employed by both the US Navy and Marine Corps. The RF-8A was a version of the F-8 Crusader series. Besides identifying possible enemy targets, it would return once a target was struck to verify the results. (US Navy)

Marine UH-34 helicopters are shown here refuelling on a South Vietnamese beach. In theory, the UH-34 was taken into service by the Marine Corps in 1957 only as a utility (jack-of-all-trades) helicopter. However, when procurement of a larger dedicated assault troop transport helicopter failed to materialize, the UH-34 filled in as a stop-gap assault troop transport in South Vietnam until 1969. (USMC)

The M14 rifle-equipped Marines in the foreground are seen here lining up for transport by the UH-34 helicopters in the background. The helicopter had the unofficial nickname of the ‘Dog’, based on the last letter of its designation. Another popular unofficial nickname for the helicopter was ‘HUS’, based on its original pre-1962 designation as the HUS-1. (USMC)

The troop compartment of the UH-34 as pictured here was placed directly under the main transmission and rotor, with the pilots and engine in front, counterbalanced by a long tail structure in the rear. The cabin measured over 13ft long, almost 5ft wide and was 6ft high with a large sliding door on the right side. There were canvas bucket seats for twelve passengers. (USMC)

The Marine Corps UH-34s and all the other helicopters of its time were both unarmoured and slow, making them extremely vulnerable to enemy ground fire, especially when approaching or departing from landing zones. One of the most dangerous threats came from the Soviet-designed, optically-guided tripod-mounted DShKM 1938/46 machine gun pictured here that fired a 12.7mm round. (USAF Museum)

Visible in this photograph from the interior of a Marine Corps UH-34 helicopter in South Vietnam is the side door gunner armed with an M60 machine gun. Before the fitting of the M60, the UH-34s in the theatre had Second World War-era Browning M1919A4 air-cooled .30 calibre machine guns. (USMC)

The optically-guided ZPU-23-2 shown here had two automatic 23mm cannons. Introduced into Soviet Army service in 1960, it had a practical rate of fire of 400 rounds per minute. The ZPU-23-2 would be supplied to the North Vietnamese Army in large numbers and, firing a high-explosive (HE) round, took a heavy toll of American military helicopters during the Vietnam War. (Vladimir Yakubov)

A Soviet-designed anti-aircraft gun supplied to the North Vietnamese Army in large numbers would be the optically-guided M1939 (61-K) anti-aircraft gun pictured here. Armed with a 37mm automatic cannon, it had a rate of fire between 160-170 rounds per minute. It had a maximum effective range of approximately 3 miles and an effective ceiling of 16,000ft. (Vladimir Yakubov)

In this illustration, we see the theoretical table of organization and equipment (TO&E) for the 3d Marine Division when it achieved full strength in South Vietnam at the end of 1965. Of the approximately 20,000 men in the division, its core fighting strength consisted of its three infantry regiments totalling 7,500 men. Supporting fire for the infantry regiments came from a single artillery regiment of around 2,800 men. (USMC)

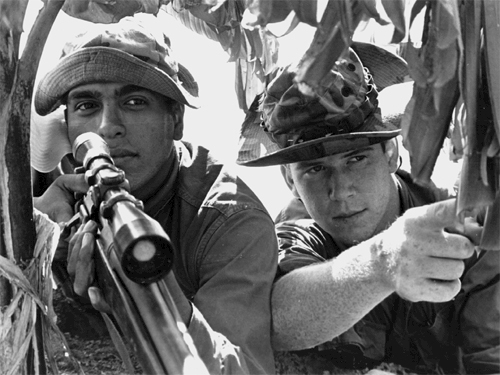

The headquarters battalion for a Marine division oversaw a scout-sniper platoon broken down into two-person teams. One was armed with a dedicated long-range sniper rifle as seen in this photograph, and his spotter with a standard infantry rifle. Reflecting their label, the primary role of the scout-sniper teams was reconnaissance and surveillance in support of Marine infantry battalions. (USMC)

Each of the three infantry regiments of a Marine division in 1965 was subdivided into three infantry battalions of 1,193 men. The individual infantry battalion was directed by a headquarters and service company of 329 men. Marine infantry battalions had little organic transport and, if not provided with attached vehicles or helicopters, walked everywhere. (USMC)

Each Marine infantry battalion had four infantry companies with a combined total of 864 men, each overseen by a nine-man headquarters section. In theory, infantry companies were to be commanded by captains but were often commanded by lieutenants due to casualties. The belted rounds carried by the Marine pictured here were for an M60 machine gun. (USMC)

Each Marine infantry company of 216 men was further subdivided into three infantry platoons of forty-seven men each and a single weapons platoon of sixty-six men. The three rifle platoons were each subdivided into three squad fire teams composed of four men each. Of those four men, one would be assigned as the fire team leader and normally held the rank of corporal. (USMC)

Eventually, Marine squads received the M79 Grenade-Launcher pictured here. The single-shot weapon could fire a 40mm high-explosive (HE) grenade out to a maximum range of 427 yards. It could also fire other munitions, including a smoke round. It had unofficial nicknames including ‘Bloop Gun’ and ‘Thumper’ for the sound it made when fired. (USMC)

In each M14 rifle-equipped Marine fire team, one of the four men bore the title ‘automatic rifleman’. He had a modified version of the M14 rifle optimized for fully-automatic fire, designated the M14A1. The main source of firepower for Marine platoons would be the M60 machine guns, as shown here, that belonged to the infantry company’s weapons platoon. (USMC)

The mortar section of the weapons platoon in Marine rifle companies had a non-commissioned officer (NCO) that oversaw three 60mm mortar squads. Each mortar squad of five men operated a single 60mm M19 Mortar as shown here. The M19 had a sustained rate of fire of approximately eighteen rounds per minute and a maximum range of just under 2,000 yards. (USMC)

The larger 81mm Mortar M29 pictured here appeared at the Marine infantry battalion levels in the battalion headquarters and service company. It had entered into service in the early 1960s with an improved version labelled the M29A1. With a sustained rate of fire of eighteen rounds per minute, it had a maximum range of approximately 3 miles. (USMC)

Also located in the battalion headquarters and service company of Marine infantry battalions was a small assault section. It had a few of the 3.5in M20 Rocket-Launchers as seen here. Better known by its popular nickname of the ‘Bazooka’, the M20 did not appear in American military service until after the Second World War, but did see service with the Marine Corps during the Korean War. (USMC)

The eventual Vietnam War replacement for the Marines’ 3.5in M20 Rocket-Launcher proved to be the M72 Light Anti-tank Weapon (LAW) pictured here. It was a self-contained one-shot, disposable, shaped-charge anti-tank rocket-launcher. Weighing 2lb, it had a maximum effective range of 328 yards at point targets. (USMC)

The most powerful anti-tank weapon found in the 1965 Marine Division TO&E was the M40 106mm Recoilless Rifle pictured here that appeared in service with the Marine Corps after the Korean War. It weighed 461lb on a tripod and fired a 37lb shaped-charge, high-explosive (HE) anti-tank warhead with a maximum effective range of about 8,000 yards. (USMC)

The Marine Corps had made very successful use of its man-portable flame-throwers during the Second World War and continued to value them post-war. By the time of the Vietnam War, the version employed would be designated the M9A1-7 seen here in use. Often used in terrain clearance, it also remained effective against enemy bunkers during the conflict. (USMC)

Due to the weight of the M40 106mm Recoilless Rifle, the Marine Corps had a couple of vehicles that could carry it into action. These included the vehicle pictured here which had a couple of official designations including the M274 Truck Platform Utility 0.5-ton 4×4. To many it was known by various unofficial nicknames, such as the ‘Mule’ or the ‘Mechanical Mule’. (USMC)

The six recoilless rifles of the Multiple 106mm Self-Propelled Rifle M50A1 were attached to a small pivoting fixture on the very top of the three-person hull that allowed the weapons to be elevated and traversed. The weapons had a maximum traverse of 40 degrees to either side of the vehicle’s centreline and a maximum elevation of 20 degrees. (USMC)

The very ungainly-looking vehicle shown here in Marine Corps’ service during the Vietnam War was the Multiple 106mm Self-Propelled Rifle M50A1 and officially nicknamed the ‘Ontos’ (Greek: the ‘thing’). Allis-Chalmers built 360 examples of the vehicle for the Marine Corps with the first production unit delivered on 31 October 1956. (USMC)

The single artillery regiment in the TO&E of the 1965 Marine division had four different weapons. The most numerous, pictured here, was the towed 105mm Howitzer M101A1 that had entered service with the Marine Corps during the Second World War. The weapon’s maximum rate of fire was ten rounds per minute for the first three minutes, with a sustained rate of fire of three to five rounds per minute. (USMC)

Dating from the Second World War but seeing service during the Vietnam War in a Marine division’s artillery regiment would be the 4.2in (107mm Mortar) M30 shown here. The weapon, unofficially nicknamed the ‘four-deuce’, fired a 27lb HE round to an approximate range of 3 miles. It normally took an eight-man team to service the weapon. (USMC)

Due to its 650lb weight when in firing order, the 4.2in (107mm Mortar) M30 could only be moved short distances by its crew. To overcome this drawback, the Marine Corps came up with a makeshift arrangement of mounting the weapon on the towed gun carriage of the obsolete 75mm M1 Pack Howitzer. The resulting weapon received the designation M98 and the unofficial nickname of the ‘Howtar’. (USMC)

The largest towed artillery piece in a 1965 Marine division would be the M114A1 155mm howitzer pictured here. Like the 105mm Howitzer M101A1, the weapon’s design dated from the Second World War. It had a maximum effective range of about 9 miles with a 95lb HE round. Unlike the M101A1 which was classified as a light artillery piece, the M114A1 received the classification of a medium artillery piece. (USMC)