On taking office in January 1969, President Nixon swiftly concluded that there would be no quick negotiated end to the Vietnam War. The only option at that point was a gradual hand over of the conduct of the war to the ARVN in a process labelled ‘Vietnamization’, a policy that had failed for the French in the 1950s. American military forces would be withdrawn in stages, as the ARVN gradually took over the fighting.

When Vietnamization began in early 1969, everybody knew it would not happen overnight. The III MAF would, therefore, continue search-and-destroy operations in the unpopulated northern hinterlands of I Corps to keep the enemy from massing their forces. In populated areas, the term ‘cordon and search’ would be applied.

Another continuing goal for the 1st Marine Division in 1969 would be the securing and pacification of as much of I Corps’ populated coastal regions as possible. The objective would be the eventual handing over of its security to the ARVN. From an III MAP report outlining its plans for 1969 appears the following passage: ‘Operations to annihilate the enemy, while clearly essential to pacification, are by themselves inadequate. The people must be separated and won over from the enemy.’

The operations conducted by the 3d Marine Division in the northern I Corps during the early part of 1969 did not come without cost, with 130 Marines killed and 920 wounded. According to the Marines, they accounted for 1,617 enemy dead and the seizure of a massive amount of supplies. In conjunction with ARVN units and US Army units, the Marines of the 3d Division continued in pursuit of enemy units and supply bases in northern I Corps until the summer of 1969.

In March 1969, Melvin R. Laird, President Nixon’s Secretary of Defense, visited South Vietnam on a fact-finding mission. Based on his quick visit to the country, he concluded that Vietnamization was already going so well that up to 50,000 American military personnel could be withdrawn from South Vietnam by late 1969, with more the following year.

Laird’s positive spin on Vietnamization was for American public consumption. He knew, as did others at senior levels of the US government and military, that the ARVN had no chance of success against the NVA / VC when American military forces finally withdrew. That information appeared in the National Security Memorandum No. 1, dated 1 February 1969, as seen in the following extracts from that document:

The RVNAF alone cannot now, or in the foreseeable future, stand up to the current North Vietnamese-Vietcong forces . . . The enemy have suffered some reverses but they have not changed their essential objectives and they have sufficient strength to pursue these objectives. We are not attriting his forces faster than he can recruit or infiltrate.

The MACV selected for initial reassignment both a US Army division and the 3d Marine Division. Rather than pulling out all their men and equipment at the same time, these divisions would depart from South Vietnam in two phases.

General Abrams, the commander of the MACV, explained his reasoning for selecting the Marine division: ‘Because it could go to Okinawa; because it would be leaving the area to the 1st ARVN Division, recognized by all as the strongest and best ARVN division; and finally, because northern I Corps has one of the best security environments in the country for the people.’

The commanders of the III MAF and FMF/Pac were a bit miffed that General Abrams scheduled no Marine aviation units for redeployment to Okinawa. In the end, some aviation elements of the 1st MAW did return to Okinawa with the 3d Marine Division, if only for training purposes.

The first elements of the Marine 3d Division departed South Vietnam on 15 June 1969, the last five months later on 24 November 1969. The first Marine aviation unit to leave South Vietnam by both air and sea began on 13 August 1969.

In early June 1969, Nixon signalled his desire to see further troop reductions, stating that he would decide on the matter in August 1969. Former Secretary of Defense Clark Clifford proposed, in a magazine article that summer, the withdrawal of 100,000 troops by the end of 1969 and the remainder the following year.

A Terrible Milestone

On 3 April 1969, the MACV officially acknowledged that more American military personnel had been killed up to that point in the Vietnam War than in the Korean War of 1950 to 1953. In the latter, 33,629 were killed and in the former 33,641 had died by that date.

Following a consultation with the American Joint Chiefs of Staff, President Nixon addressed the American public via a television broadcast on 16 September 1969. He informed them that the planned pull-out of 50,000 men from South Vietnam by the end of 1969 would be increased by 20 per cent to 60,000.

On the evening of 3 November 1969, Nixon once again went on television to announce to the American public a non-specific deadline for further pull-out of American military personnel: ‘This withdrawal will be made from strength and not from weakness. As South Vietnamese forces become stronger, the rate of American withdrawal can become greater.’

Nixon announced on 15 December 1969 that he wanted 50,000 additional troops pulled from South Vietnam by 15 April 1970. Of that number, 12,900 would be Marines. The Marine Corps commandant at the time, General Leonard F. Chapman Jr, remembered: ‘I felt, and I think that most Marines felt, that the time had come to get out of Vietnam.’

While the 3d Marine Division, operating in the unpopulated northernmost province of I Corps, fought a mainly conventional war against NVA divisions until its departure, the opposite would be true of the 1st Marine Division defending southern I Corps. Within their zone of operation were the western mountains that the NVA had to transit before threatening the Da Nang air base and I Corps’ densely populated coastal regions.

Colonel Robert H. Barrows recalled in a 1987 interview by the Marine Corps Historical Center how difficult it was for the men of the 1st Marine Division throughout 1969:

Those Marines who went out day after day conducting . . . combat patrols, almost knowing that somewhere on their route of movement, they were going to have some sort of surprise visited on them, either an ambush or explosive device . . . I think that is the worst kind of warfare, not being able to see the enemy. You can’t shoot back at them. You are kind of helpless.

Lance Corporal Lester W. Weber’s response to not being able to get to grips with an often-elusive enemy appears in an extract from his Medal of Honor citation. The date is 23 February 1969, and when his platoon came under heavy fire from concealed enemy soldiers he sprang into action:

He reacted by plunging into the tall grass, successfully attacking one enemy and forcing eleven others to break contact. Upon encountering a second North Vietnamese Army soldier, he overwhelmed him in fierce hand-to-hand combat. Observing two other soldiers firing upon his comrades from behind a dike, Lance Corporal Weber ignored the frenzied firing of the enemy and, racing across the hazardous area, dived into their position. He neutralized the position by wrestling weapons from the hands of the two soldiers and overcoming them . . . As he moved forward to attack a fifth enemy soldier, he was mortally wounded.

For the men of the 1st Marine Division on constant patrol, mines and booby traps set by the enemy took a heavy psychological toll. Colonel Charles S. Robertson noted in a Marine Historical Center interview, ‘the bulk of casualties resulted from the abundance of surprise firing devices’ instead of engagements with enemy forces.

Lieutenant Colonel Godfrey S. Delcuze noted in a July 1978 interview:

The war had moved on except for sporadic, murderous local force mining. Brave men died ‘pacifying’ old men, women and children who refused to be pacified . . . They – the peasants – wreaked their havoc from time to time with M16 bouncing mines from fields US Forces had laid. The only identifiable ‘military’ service was a two-day lay-out ambush. The ambush netted one enemy soldier. He came walking down a trail with an M16 bouncing mine in each hand. We shot him in the gut. He was a 12-year-old boy.

To deal with the threat faced by Marines of the 1st Division from mines and booby traps, the division employed many different methods to reduce losses. These included bombarding with artillery and napalm the areas to be searched before the Marines’ arrival. Once on site, the Marines would conduct the majority of their movements whenever possible mounted on armoured tracked vehicles. If forced to advance on foot, maximum dispersion was stressed to prevent a single mine or booby trap from killing or wounding more than one Marine at a time.

From a US Army manual titled Booby Traps issued in September 1965 is this extract describing their purpose: ‘Booby traps supplement minefields by increasing their obstacle value . . . cause uncertainty and suspicion in the mind of the enemy. They may surprise him, frustrate his plans, and inspire in his soldiers a fear of the unknown.’ Some 11 per cent of American deaths during the Vietnam War were attributed to enemy mines and booby traps, with another 17 per cent wounded by the devices.

In spite of continuous patrolling by the Marines of the 1st Division during the first six months of 1969, it proved impossible to stop small-scale enemy attacks on both Marine and civilian targets. To curtail this problem, the 1st Marine Division would mount even more small and large-scale operations in the last six months of 1969.

Not counting the threat from the enemy, both the terrain and climate of South Vietnam often proved to be a hardship for Marines. Lieutenant Colonel Ray Kummerow commented in a 1983 Marine Corps Historical Center interview:

[It] was ‘billy goat’-type scramble from peak to peak, trying to maintain communications and cover of supporting arms . . . We were surprised at the casualties sustained from malaria and other diseases after a month of continuous fighting in that environment. The battalion dwindled to half field strength. India Company lost all its officers save the company commander . . . who requested relief because of fatigue.

By the end of 1969, approximately 55,000 Marines remained under III MAF control in South Vietnam. Of that number, 28,000 belonged to the 1st Marine Division. With the redeployment of some of its assets beginning in January 1970, by March of 1970 it would drop to only 21,000 personnel.

The main job for the remaining units of the 1st Marine Division in 1970 would be the continuation of the security and pacification activities from the previous year. Also, it would continue to assist in the process of Vietnamization and preparing itself for the orderly withdrawal of additional elements of the division from South Vietnam. The then commandant of the Marine Corps stated: ‘Don’t leave anything behind worth more than five dollars.’

Did the effort that the III MAF put into pacification ever have any chance of success? Some Marine senior officers touted its success. Lieutenant General McCutcheon of the III MAF stated in 1970 that despite ‘improved ratings in the Hamlet Evaluation system’, the majority of the rural population of South Vietnam remained equally ‘apathetic’ to their own government or to the enemy, and considered the Vietnamization process as ‘a euphemism for US withdrawal’.

The 12,900 Marines planned to be withdrawn from South Vietnam by 15 April 1970; as Nixon ordered, they would end their combat operations beginning in late January 1970. With their departure, US Army personnel in I Corps exceeded the number of Marines. The result was that the III MAF became subordinate to the US Army XXIV Corps command on 9 March 1970.

With the continuing drawdown of the 1st Marine Division, large-scale battalion-sized and larger operations became far less common. When the Marines did venture out in force to search for enemy base camps, their efforts did not always have the desired effect. The enemy had learned, when given the opportunity, to build more base camps than they required to offset those destroyed during Marine search-and-destroy operations.

An enemy defector stated:

The people in the base camp do not worry about allied operations. Forewarning of an attack is obvious at the base camp when FWMAF [Free World Military Armed Forces] conduct air strikes, artillery fire, aerial reconnaissance, and when helicopters fly in the area. When an operation takes place in the vicinity of the base camp, the people simply go further back into the mountains and return when the operation is over.

In the endless patrols by the 1st Division Marines during the first six months of 1970, individual Marines continued to perform acts of incredible bravery. On 8 May 1970, machine-gunner Lance Corporal Miguel Keith’s platoon came under attack by a superior enemy force. Despite being wounded in the initial barrage of enemy fire, he continued to fire upon them. In an extract from his Medal of Honor citation we see what then transpired:

At this point, a grenade detonated near Lance Corporal Keith, knocking him to the ground and inflicting further severe wounds. Fighting pain and weakness from loss of blood, he again braved the concentrated hostile fire to charge an estimated twenty-five enemy soldiers who were massing to attack. The vigor of his assault and his well-placed fire eliminated four of the enemy while the remainder fled for cover. During this valiant effort, he was mortally wounded by an enemy soldier.

Anarchy in the Ranks

With the end of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War in sight and nobody wanting to be the last man killed, Marine morale began to slide. The decreased morale resulted in a host of issues including a breakdown in discipline and increased drug abuse by Marines. Senior officers believed that by 1970 somewhere between 30 and 50 per cent of their men had some involvement with drugs. To make up for the high losses suffered by the Marine Corps in the Vietnam War, recruitment standards had been lowered and training shortened.

Another grave issue was violence among the ranks, such as whites against blacks. These incidents included large-scale race riots, both on Marine bases in South Vietnam and in the United States. On a smaller scale, the white v. black confrontations included individual fights, muggings and even robberies. However, in the field the problem was not nearly as serious as all faced a common enemy.

An additional issue revolved around the growing degree of violence between enlisted men and their officers. In a Marine Corps Historical Center publication Colonel Robert H. Barrow stated: ‘This war has produced one form of felony that no other war has ever had; more despicable and inexplicable thing [than] in any other wars that I have ever seen . . . And that is the felonious attack of one Marine against another, very often with a hand grenade . . . I don’t think anybody ever recalls some officers or some NCO being killed in combat by his own troops intentionally. In Vietnam, yes. We had several of these.’

To show that neither the ARVN nor the Marines could protect them within I Corps, VC main force units attacked two pro-South Vietnamese villages on 11 June 1970. At the first, they killed seventy-four and wounded many others. In the second they killed 150 civilians and injured another 60. A Marine recalled:

The enemy ran through the village, ordering people out of their bunkers. When they did [come out], they were shot, or else [the enemy threw] chicoms [grenades] into the bunker, killing the men, women, and children in them . . . Very many civilians [were] killed just inside their bunkers, if it wasn’t from shrapnel wounds it was from fire where they were burned to death from the satchel charges used.

As in the past, the results of the various operations undertaken by the 1st Marine Division during the first six months of 1970 proved hard to measure. The enemy tended to avoid any large-scale activities during that time and merely sought to inflict on the Marines as many casualties as possible with minimal effort. The Marines were therefore engaged in what had become a slow, bloody war of attrition. They claimed 3,955 enemy dead for the loss of 283 killed and 2,537 wounded during that period.

In spite of its ever-reducing numbers, the 1st Marine Division continued with offensive operations in the latter part of 1970. The last major operation of the division received the name IMPERIAL LAKE and would be in conjunction with both US Army and ARVN units. The operation began on 1 September 1970, and ran until May 1971 with the goal of clearing an enemy-occupied area located 20 miles south of the Da Nang air base.

As the Marines uncovered enemy base camps and tunnels during Operation IMPERIAL LAKE, according to a Marine Corps Historical Center publication: ‘They blew up the structures with plastic explosive and seeded caves with crystallized CS riot gas. If the enemy reoccupied a seeded cave, the heat from their bodies and from lamps or cooking fires would cause the CS to resume its gaseous state, and render the cave uninhabitable.’

The Unwilling

In April 1970, the Marines announced that they would stop taking draftees; something they had never been comfortable doing but it had become necessary due to a lack of sufficient volunteers. In total, the Marine Corps took in 42,000 draftees during the Vietnam War.

By 1 September 1970, the III MAF had dropped to 24,527 personnel, with around 12,500 belonging to the 1st Marine Division. The remaining Marines were spared heavy combat with the enemy during the year’s last four months. Some thought that poor weather conditions and extensive flooding had curtailed enemy offensive operations. For the Marines, this proved a fortunate event as it forced the usually hidden enemy to the surface. In some locations they were quickly spotted and eliminated.

Major John S. Grinalds, the intelligence officer (S-2) of the 1st Marine Division, had a different view on the lack of enemy activity during the latter part of 1970. He believed that the enemy had a master plan which involved allowing the American military to withdraw from South Vietnam mostly unhindered, with just enough activity to remind both the South Vietnamese and American public that the war remained in effect, but not enough to be seen as a significant threat that might cause the American military to slow down withdrawal from the country.

Major Grinalds would go on to later state that he ‘expected the enemy to bide their time, building up their supply stockpiles, and recruit more guerrillas and VCI [VC infrastructure] members, while they weakened civilian confidence in the South Vietnamese government by continued terrorism and propaganda’. Then, as Grinalds put it, ‘in July [1971], when we finally stepped out, they could come in with their main force units and either act politically or militarily to . . . control the area.’

The high-minded goals of Vietnamization that allowed the 1st Marine Division to depart from South Vietnam eventually left the security of the country in theory in the well-prepared hands of the ARVN and its various types of militia units. That was not to be possible for myriad reasons. These included the complex web of political ties among the South Vietnamese military elite that ran the country, meaning that personal loyalty typically counted more than military competence in achieving rank.

A Marine general complained in August 1970 that the ARVN senior leadership had ‘little appreciation for the time and space factors involved in an operation, nor of the logistic effort required to support one’. An example of the ARVN’s sometimes indifferent attitude to Marine efforts on their country’s behalf would be the well-equipped and highly-trained units they were operating near the Da Nang air base in 1970. A Marine officer recalled that ‘they [the ARVN] never provided any support to anyone within the area immediately around Da Nang.’

At the lower scale of operations, those Marines involved in small unit security and pacification roles at the village level often found that the ARVN militia units would not always be around when the fighting started. A Marine corporal recalled

that initially in night firefights . . . you’d look around and . . . there wouldn’t be no PFs [Popular Force militiamen] there. They’d be hiding behind gullies, bushes, trees, anything you could find down on the ground, in a hole. After a while they’d see that we was getting up, was going into it. Course you had every once in a while to knock a few heads and put a few rounds over the top of ’em, but they finally got to where they started to go with us.

By the end of 1970, Marines at the local levels had improved some of the ARVN militia units. They would sometimes even mount offensive actions against local enemy units. However, the Marines who worked with them commented that the militia leadership failed to grasp that to be successful at deterring the enemy from attacking they had to keep continuous pressure on the enemy and should not immediately withdraw to their fortified camps upon the conclusion of offensive actions.

American advisers had moulded the ARVN in the image of the US Army. Superficially it presented a facade of strength, possessing many of the trappings expected of a modern army such as tanks or artillery. However, behind the facade, it lacked a suitable logistic infrastructure or the trained specialists and equipment that kept the American military up and running.

Most serious among the ARVN’s shortfalls were those of their fixed-wing or helicopter assets. The MACV would be fully aware of this issue, but given the timetable imposed by Nixon for the American military withdrawal from South Vietnam, not much could be done to rectify it in time.

On the first day of 1971, the relationship between the local ARVN forces and the Marine 1st Division changed. The former now had full responsibility for the security of the countryside. The latter, reflecting their ever-dwindling numbers, were now tasked primarily with the protection of the Da Nang air base, although two infantry regiments of the 1st Marine Division remained in the field for the time being.

By early April 1971, only a single regiment of the 1st Marine Division remained in South Vietnam. Their orders stressed that if they encountered a superior enemy force they were to withdraw and allow artillery to deal with them. On 14 April 1971, the III MAF relocated to Okinawa. Command of the last Marine ground troops in South Vietnam passed the same day to the just-activated 3d Marine Amphibious Brigade (MAB).

The last search-and-destroy operation conducted by the men of the 1st Marine Division bore the name Operation SCOTT ORCHARD. It began on 7 April and ended on 11 April 1971, with no losses for the Marines. On 11 April 1971, Nixon welcomed home the initial elements of the 1st Marine Division at Camp Pendleton, located in Southern California.

On 7 May 1971, Operation IMPERIAL LAKE concluded. It had lasted eight months and had cost the Marines 24 dead and 170 wounded. The Marines claimed at least 300 enemy dead in exchange. On the same day that Operation IMPERIAL LAKE ended, the Marine Corps ceased all ground combat operations in South Vietnam.

All Marine Corps security and pacification efforts were turned over to the ARVN on 11 May 1971. By this point, the resentment of the South Vietnamese (both military and civilian) had become a serious problem as they felt they were being abandoned by the United States. In some incidents they threatened and even fired their weapons at Marines.

In a Marine Corps Historical Center publication appears this statement from the senior province advisor within the I Corps area on 3 March 1971: ‘Anti-foreign [American] feeling continues at an endemic level. Incidents are becoming more numerous and testy . . . Further increases can be expected as opportunists will use incidents to further nefarious ends.’

On 26 May 1971, the last Marine air combat unit departed from South Vietnam. The 3d MAB turned over to the US Army the last piece of ground under its control on 4 June and closed its headquarters on 26 June. It deactivated on the following day.

The only ground force Marines remaining in South Vietnam at the end of June 1971 were approximately 500 men assigned to liaison and advisory duties. They began leaving the country in March 1973, much to the consternation of the ARVN. At that point the only remaining Marine ground troops in South Vietnam were 143 men assigned to guard the American Embassy in Saigon.

The Toll

During the Marine Corps’ time in South Vietnam from 1965 till 1973, more than 500,000 Marines had spent some time in the country. Of those who served, 13,005 had died and another 88,635 were wounded. The Vietnam War Memorial in Washington DC, however, lists 14,809 Marine dead during the Vietnam War. These losses were higher than those sustained by the Marine Corps during the Second World War. Those came to 25,511 dead and 68,207 wounded. Improvements in medical care helped to keep down the count of Marine dead during the Vietnam War.

On 30 March 1972, the NVA launched their Easter Offensive aimed at the overthrow of the South Vietnamese government. To provide much-needed aerial support for the ARVN, the American government committed a number of Marine air combat squadrons, which flew out of the Da Nang air base and Thailand.

The US Navy and Air Force also contributed assets to the fight. With that air support, the ARVN managed to turn back the enemy offensive by 22 October 1972. The last Marine air combat squadrons had departed South-East Asia the month before on 1 September 1972.

The last Marine embassy guards left South Vietnam by helicopter with the fall of the country’s government on 30 April 1975. The NVA offensive that led to the end of the Vietnam War had begun the previous month and had quickly overwhelmed the ARVN, which had been denied American air power this time around. The reason was that the American public and its political representatives in Congress had wanted no more involvement in the long-running conflict, knowing that the South Vietnamese government was doomed.

A Marine Corps military police bunker guarding one of the roads leading to the Da Nang air base. At the beginning of 1969, the III MAF under the command of General Robert E. Cushman consisted of approximately 81,000 Marines roughly divided among the 1st and 3d Marine divisions and supporting troops. There were another 15,500 men that made up the 1st MAW that also came under the oversight of the III MAF. (USMC)

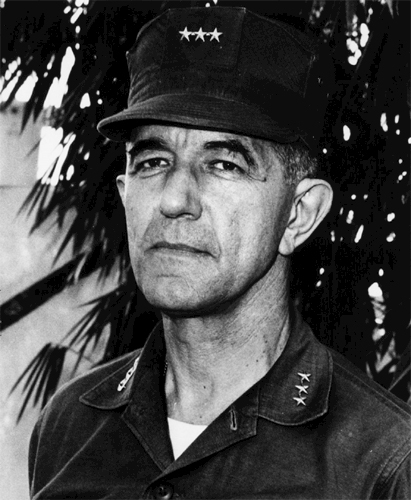

On 26 March 1969, Lieutenant General Herman Nickerson, Jr, pictured here, replaced General Robert E. Cushman as commander of the III MAF. Like all the other senior-ranking generals of the Vietnam War era, he was a much-decorated veteran of both the Second World War and the Korean War. He had served as the commander of the 3d Marine Division from October 1966 to May 1967. (USMC)

An M109 155mm self-propelled artillery howitzer in a secure rear area, based on the posture of the Marine crew. Besides all its Marine units, the III MAF also oversaw approximately 50,000 US Army personnel within the I Corps Tactical Area of Responsibility (TAOR) in 1969. The US Army units had been transferred to command of the III MAF the previous year by the MACV. (USMC)

On 17 April 1969, the US Army in South Vietnam transferred some of its M107 175mm self-propelled guns as seen here to the III MAF. They were the intended replacements for three M53 155mm self-propelled gun batteries. All of the artillery assets of the 1st Marine Division fell under the command of the 11th Marine Regiment and those of the 3d Marine Division under the 12th Marine Regiment. (USMC)

The Marine M110 8in self-propelled howitzer pictured here in South Vietnam and the M107 175mm self-propelled gun were mounted onto the same low-profile tracked chassis. That chassis received power from a diesel engine. The only armour protection on the vehicle existed for the driver who resided in the left front side of the vehicle with the engine located to his right. (USMC)

The combined strength of the 11th and 12th regiments in 1969 came in at 242 howitzers, guns and 4.2in (107mm) mortars. The most numerous divisional towed artillery piece throughout the Marine Corps’ involvement in the Vietnam War would be the Second World War-era M101A1 105mm towed howitzer pictured here. (USMC)

The main mission for Marine Corps’ artillery in the Vietnam War would be to provide fire in support of offensive operation and defensive operations. Besides providing fire support for the Marine units if called upon, the 11th and 12th Marine regiments would answer calls for fire support from US Army units as well as ARVN units. In addition, they would sometimes be called upon to fire their weapons in support of the South Korean Marine units that served during the conflict. (USMC)

Here a Marine is loading an HE (high-explosive) round into the breech of the 155mm howitzer found on the M109 self-propelled howitzer. Marine artillery regiments were often called upon to prepare landing zones and fire support bases for friendly occupation by blasting away vegetation for helicopters to land. These fire missions would often entail a minimum of 1,000 rounds of ammunition. (USMC)

Seen here in full recoil is the barrel of a Marine M114A1 155mm towed howitzer. A common fire mission would be in the suppression role, engaging suspected enemy bases as well as artillery, rocket or mortar sites. These missions went by the names ‘unobserved’, ‘harassing’ or ‘interdiction’ fires. They were initiated by specific intelligence from informants, radar or even radio intercepts. (USMC)

In January 1969, the III MAF had a total of 258 fixed-wing aircraft such as the A-4 Skyhawks pictured here and 270 helicopters. Most of the fixed-wing Marine aircraft flew out of the Da Nang air base. By way of comparison, the MACV had under its control approximately 740 fixed-wing aircraft mostly from the USAF and about 3,400 helicopters, the majority belonging to the US Army. (USMC)

The terrain and weather of South Vietnam often made it difficult to see the enemy or determine the effectiveness of aircraft sorties. Poor weather conditions or night-time sorties often called for the use of an Air Support Radar Team (ASRT) which vectored aircraft, such as the A-6 Intruder shown here, to their targets with input from seismic and acoustic ground sensors. (USMC)

An F-4 Phantom II of the 1st MAW with a full bomb load. At first, Marine pilots dropped their bombs from lower than 200ft for the best accuracy. However, this would eventually be increased to a minimum of 300ft for safety reasons to prevent fixed-wing aircraft finding themselves caught in the explosions of their own bombs at low levels. The US Navy developed bomb-retarding kits that accordingly came into use with the 1st MAW. (USMC)

Besides large numbers of enemy anti-aircraft guns (both optical and radar-guided) of different calibres posing a threat to the aircraft of the 1st MAW, a new threat appeared possibly as early as 1968. That was the Soviet-designed and supplied 9K32 Strela-2 surface-to-air anti-aircraft missile seen here in the hands of an NVA soldier. To the American military, it was known as the SA-7 Grail. (USMC)

In this picture we see ARVN soldiers and their advisers rushing supplies out of a Marine UH-34 helicopter, no doubt under enemy fire. The piston-engine-powered UH-34 helicopter would finally be retired from service in South Vietnam in early August 1969. From 1965 until 1969 they flew over 917,000 sorties, and were replaced by the CH-46 Sea Knight and the CH-53 Sea Stallion. (USMC)

In 1969, the first examples of the improved CH-46D model Sea Knight helicopters arrived in South Vietnam to replace the earlier trouble-plagued CH-46A version. All of the existing examples of the latter would be eventually upgraded to the ‘D’ model standard. With a more powerful engine, the later model of the Sea Knight could lift 2,720lb whereas the older model was limited to 1,710lb under combat conditions. (USMC)

A view inside a Marine CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter during the Vietnam War. From a 1969 Marine report on helicopters’ use appears this passage: ‘Viewing the nature of the war, the terrain, and the enemy . . . we never had enough helicopters to satisfy the needs and requirements of the two divisions.’ The resulting overuse of the existing helicopters therefore greatly shortened their intended service lives. (USMC)

The CH-46 Sea Knight typically had two .50 calibre machine guns for self-defence. The helicopters of the 1st MAW during the first six months of 1969 were flying between 47,000 to a high in April 1969 of 52,000 sorties a month. One of the problems that resulted from these high sortie rates was an excessive incidence of pilot fatigue that in turn raised the accident rate. (USMC)

On 10 April 1969, the first of twenty-four AH-1G Cobra gunships as seen here arrived in South Vietnam. The tandem-seat dedicated helicopter gunship carried an array of weapons ranging from 40mm grenade-launchers to 2.75in rockets. It was the replacement for the UH-1E Huey in the gunship role. The UH-1E then reverted to its original role as an observation platform. (USMC)

In the name of pacification, beginning in late 1965, the Marines had a project referred to as the Combined Action Programme (CAP). It consisted of a rifle squad of Marines and a US Navy corpsman assigned to assist a local South Vietnamese militia unit in defence of its village. The Marines involved in the programme came to be known as Combined Action Platoons (CAPs). Pictured here is a patrol of local militia members. (USMC)

The III MAF put into the field Mobile Training Teams (MTTs) to improve the combat effectiveness of South Vietnamese militia units in villages that did not have a CAP in place. The militia member in the foreground is armed with an M1 Garand rifle. The M1 Garand, and the M1 and M2 American-designed and built carbines, were standard equipment for the ARVN until replacement by the M16 rifle. (USMC)

In early 1969, the American military put the enemy personnel count in South Vietnam at approximately 73,000 men. These were broken down into 42,700 NVA, another 6,500 main force VC and local force unit members with some 23,500 guerrillas. Also there was a 16,000 political and quasi-military cadre. Pictured here is what appears to be a Viet Cong main force unit planning an attack by using a model of their target. (USMC)

A Marine rifleman checks for booby traps on the corpse of what is likely a Viet Cong guerrilla, based on the fact that he has either an M1 or M2 carbine. As that weapon went to the ARVN and its militia units in large numbers, it could be a captured example. Others were stolen from supply ships or arms warehouses by South Vietnamese civilian workers. (USMC)

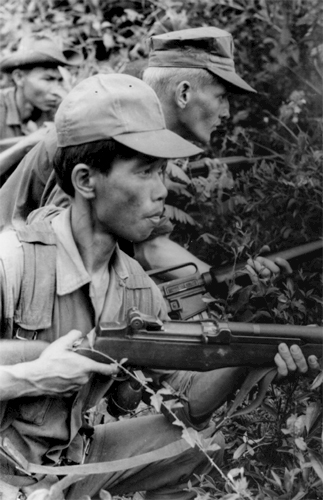

The NVA soldiers seen here tended to be better-armed and trained than their VC main force counterparts. Heavy losses incurred by the Viet Cong main force units led to their replacement in many units with NVA soldiers, a practice that had begun as early as 1964. Despite the ever-rising number of NVA soldiers in many VC main force units, they retained their VC designation to make it appear that they were indigenous people. (USMC)

In this picture, we see American President Richard M. Nixon on the left and his Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird to the right. On 3 May 1969, Laird announced that the American military would soon begin troop withdrawals from South Vietnam if certain conditions came about in theatre. These included an improvement in the fighting ability of the ARVN and a major reduction in enemy activity. (USMC)

To provide a possible cover story on how American military forces could withdraw without the collapse of the South Vietnamese military, the term ‘Vietnamization’ would be put forward by Nixon’s White House. It presumed the American military bringing the ARVN up to American performance standards. Pictured here is a Marine adviser instructing South Vietnamese Marines on the use of the 81mm mortar. (USMC)

On 12 May, the enemy struck throughout South Vietnam with the largest number of attacks since their initial Tet Offensive in January 1968. In spite of these activities, the decision to withdraw American troops remained in place. On 8 June 1969, President Nixon announced that by the end of August 1969 another 25,000 American military personnel would withdraw from South Vietnam. (USMC)

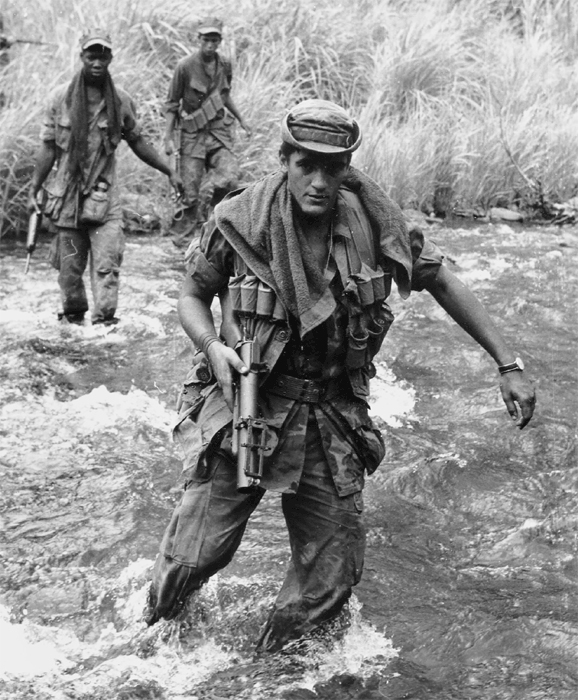

Despite the declared drawdown of American military forces, the III MAF continued with an endless series of operations to deter the enemy’s plans. These operations included constant patrolling to find the enemy, as seen here. The Marine rifleman in the foreground is carrying an M79 grenade-launcher and wearing an ammo vest with pouches to store 40mm rounds. (USMC)

A Marine rifleman and his scout dog take a break from patrolling. The enemy also employed scout dogs on occasion to locate Marine infantrymen. On 13 August 1969, the first major unit of the 1st MAW, a medium helicopter squadron, departed from South Vietnam. The squadron had been the first to arrive in South Vietnam in April 1962. (USMC)

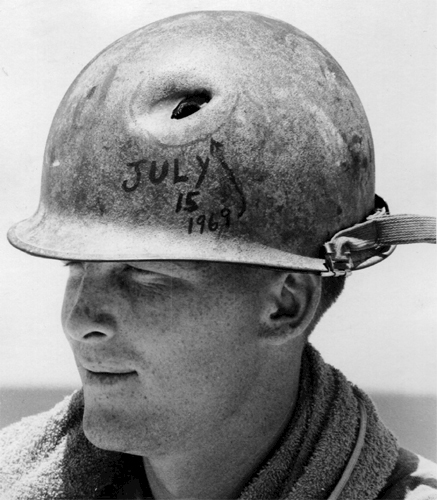

Even as the process of withdrawing Marines and other American military personnel began in early 1969, Marines continued to be attacked by the enemy in numerous engagements. The lucky Marine pictured here managed to avoid death when his helmet took a round. To remember that fortunate break, he had marked the date when the incident occurred. (USMC)

On patrol, Marine infantrymen look for enemy supplies or possibly the entrance to an enemy tunnel. In August 1969, additional Marine units began to withdraw from South Vietnam. President Nixon proclaimed on 16 September 1969 that another 40,500 men, including 18,400 Marines mostly from the 3d Division, would depart before the end of the year. (USMC)

When enemy tunnels were found, fearless volunteers nicknamed ‘tunnel rats’ would descend into them to find and dispose of those within. Pictured here is a Marine tunnel rat armed with a .45 automatic pistol exiting a tunnel. Normally when entering into the depths he would also carry a flashlight. Some of the enemy tunnels encountered during the conflict led to multi-level complexes. (USMC)

Shown are some of the items recovered by a Marine patrol from an enemy tunnel seen in the background. Visible is a Soviet Army helmet without a liner, and an 82mm mortar baseplate as well as some 82mm mortar rounds. Also visible are RPG warheads and a single mine. The minimum depth of enemy tunnels would be 4ft, with a few found as deep as 40ft. (USMC)

Throughout the Vietnam War, the enemy made widespread use of mines and booby traps. In this picture we see a Marine engineer team searching for the magnetic signal of a buried enemy mine with an electrical mine detector. The enemy had a wide range of mines from the Soviet Union and Red China, including anti-tank mines as well as anti-personnel mines. (USMC)

A Marine engineer is shown attempting to disarm an enemy mine. One of the first steps is carefully searching around and under the mine, locating and neutralizing all activation fuses. Mines are made safe by making the main fuse safe. Some anti-tank mines cannot be made safe, but as they require hundreds of pounds of pressure to detonate, they can be removed to a safe place and then destroyed. (USMC)

A Marine rifleman offers a wounded comrade a drink of water from his canteen. Every Marine in the field had a first-aid kit attached to the rear of his service belt. Its contents could differ, but typically held an assortment of bandages and medication for treating burns. The US Navy provided medical corpsmen to Marine infantry formations during the Vietnam War. (USMC)

A total of 88,635 Marines were wounded during the Vietnam War. In this photograph we see Marines rushing to place a wounded buddy onto a medical evacuation helicopter. Head wounds tended to be the most common for infantrymen and resulted in the highest death rate. Enemy mines and booby traps, even if they did not kill, often caused the loss of a limb or limbs. (USMC)

Crewmen on a Marine helicopter attend to a wounded Marine while in flight. Of those Marines killed during the Vietnam War, enemy small-arms fire accounted for 51 per cent of deaths and 16 per cent of wounded. Enemy artillery fire accounted for another 36 per cent of deaths and 65 per cent of wounded. Enemy mines and booby traps resulted in a 13 per cent death rate and 19 per cent of the wounded. (USMC)

For the most seriously injured Marines, the next-to-last step in the medical evacuation process might be transfer to a hospital ship as seen here. With the latest in medical equipment and well-trained staff, such ships could perform any necessary medical procedures. Once stabilized, the patient might be flown Stateside to a military hospital. (USMC)

Members of a Marine reconnaissance unit are shown on patrol in South Vietnam in this photograph. Interesting is the beret on the Marine in the foreground, a not very common piece of headgear. That same Marine is wearing a nonstandard camouflage uniform referred to as the ‘duck hunter’ scheme. (USMC)

A Marine scout-sniper team in action. On 15 December 1969, President Nixon announced that the third round of American military troop withdrawals from South Vietnam was to be completed by 15 April 1970. With the continued withdrawal of Marine units of the III MAF, their numbers by the end of 1969 were down to 54,559 men. (USMC)

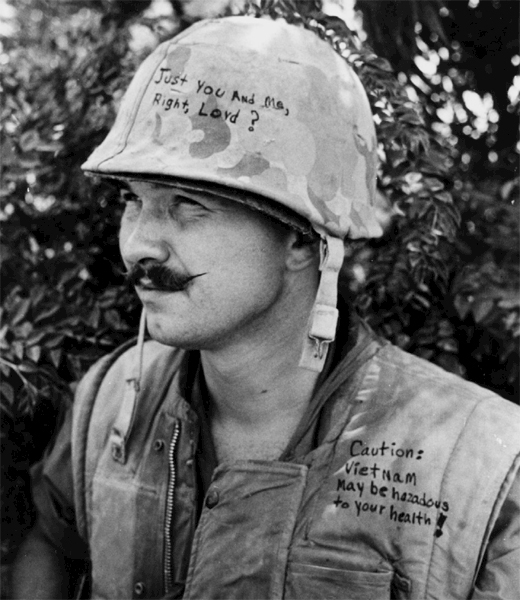

Near the end of a major Marine Corps presence in South Vietnam, some Marines began to mark up their helmet covers as shown. In spite of the continued withdrawal of American military personnel beginning in 1969 going into 1970, the enemy did not reciprocate in accord with the terms of the cease-fire agreement between the American government and the North Vietnamese government. (USMC)

A Marine is shown here rushing out of a CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter. He is carrying a 60mm mortar over his shoulder. On 17 February 1969, President Nixon claimed that the military aspects of Vietnamization were proceeding on schedule, despite those at the most senior levels of the American government and military knowing that it was a falsehood. (USMC)

A young Marine takes cover on the battlefield. Beginning in 1969, with the drawdown of Marine numbers in South Vietnam, there began a process of deactivating some Marine units in both South Vietnam and the United States. In September 1969, the 5th Marine Division would be deactivated, reflecting a planned scaled-down post-Vietnam War Marine Corps. (USMC)

On 19 February 1970, with the continuing withdrawal of Marine units from South Vietnam, the US Army personnel in the I Corps TAOR outnumbered the Marines. This led to plans to place the III MAF under US Army oversight beginning on 9 March 1970. The 3d Marine Division had departed by December 1969, leaving only the 1st Marine Division in South Vietnam. (USMC)

In July 1970, the III MAF launched two major operations aimed at denying the enemy access to the latest rice harvest within I Corps. By this time large-scale engagements had become infrequent, although the enemy would constantly engage the remaining III MAF troops in a deadly war of ambushes, small battles, and rocket and mortar attacks. (USMC)

A Marine helicopter crewman points out the enemy bullet that lodged in his APH5 helmet. By the end of 1970, the 1st Marine Division in South Vietnam had shrunk to some 12,500 men. That same month President Nixon warned the North Vietnamese government that if they continued to increase the level of fighting in South Vietnam, he would resume bombing of North Vietnam. (USMC)

Military policemen stand guard with an M2 .50 calibre machine gun. On 6 January 1971, Secretary of Defense Laird stated that Vietnamization was running ahead of schedule and that combat missions for all American military personnel would end in the summer of 1972. On the down side, the NVA had begun bringing in more heavy artillery north of the DMZ. (USMC)

Marines leaving South Vietnam line up to board a US Navy ship. In early 1971, the III MAP was down to 24,700 men. The 1st MAW had only 74 fixed-wing aircraft remaining and 111 helicopters. In April 1971, the last elements of the 1st Marine Division left South Vietnam. That same month the III MAF Headquarters departed. The only formation remaining would be the 3d Marine Amphibious Force. (USMC)

During the redeployments from 1969 to 1971, Marine logisticians successfully withdrew vast quantities of equipment. They also dismantled many of their installations or turned them over to the ARVN. Those Marine installations dismantled came about as the ARVN lacked the personnel strength to maintain or staff them. Pictured here is a Marine checking to see if the load on a semi-truck is secured correctly. (USMC)

A Marine colour guard is furling its regimental flag before it departs by ship from South Vietnam. It’s an apt moment reflecting the end of a significant Marine Corps presence in the country, except for some advisers and liaison personnel. On 4 June 1971, the 3d MAB turned over the last piece of real estate for which it had responsibility to the United States Army. (USMC)