Hitler received the news with grave displeasure two days later at his mountain retreat, the Berghof at Obersalzberg. In the great anteroom off the villa’s main hall, with its stunning views of the snowcapped Bavarian Alps, he read the report at his desk, his rage all-consuming. Hitler pushed the document away and summoned to his inner sanctum SS chief Heinrich Himmler, Air Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, and the head of armed forces, Feldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel. The three men entered the room to a ranting, gesticulating Führer and immediately began assigning blame for the debacle. Responsibility for prisoners of war lay with a division of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (Army High Command), a point the proud and always pompous Göring was quick to make clear. Keitel bristled at the insinuation and thrust a finger in Göring’s direction, reminding those present that Stalag Luft III fell under the Luftwaffe’s jurisdiction. Göring, at the war’s outset, had requested all prison camps detaining airmen be placed under his control. A fighter ace in the previous world conflict, he felt a certain kinship with those who fought in the skies. Himmler watched, seething, as Göring and Keitel verbally assailed each other, before he, too, lashed out. The manpower required to track down seventy-six escapees, he said, would prove immense. The Breslau Kriminalpolizei (Kripo, or Criminal Police)—responsible for the area in which the camp was located—had issued within hours of the escape a Grossfahndung, a national hue and cry ordering the military, the Gestapo, the SS, the Home Guard, and Hitler Youth to put every possible effort into hunting the escapees down. Nearly one hundred thousand men needed to defend the Reich were now being siphoned off elsewhere.

“It is incredible that this sort of thing should have occurred,” Himmler said. “It should not have happened.”

Mass escapes at prison camps across Germany had plagued the Reich in recent months. Forty-seven Polish officers had tunneled their way out of Oflag VI-B, a compound in Dössel, on the night of September 20, 1943. Twenty men were recaptured within four days, dispatched to Buchenwald concentration camp, and exterminated. Another seventeen were apprehended shortly thereafter and shot by the Gestapo. The remaining ten managed to get away. The night before the Polish breakout, 131 French soldiers escaped from Oflag XVII-A in Döllersheim; only two avoided recapture. Drastic measures had already been taken to prevent a repeat of such occurrences. In February, the German High Command had issued Stufe Römisch III, an order dictating that recaptured prisoners of war, “irrespective of whether it is an escape during transit, a mass escape or a single escape, [are] to be handed over after recapture to the Head of Security Police and Security Service” and not the military. “The persons recaptured,” the order stated, “are to be reported to the Information Bureau of the Armed Forces as ‘Escaped and not recaptured.’ ” Inquiries from the International Red Cross and other aid organizations were to receive the same response. Recaptured British and American officers were to be detained by the police and handled on a case-by-case basis.

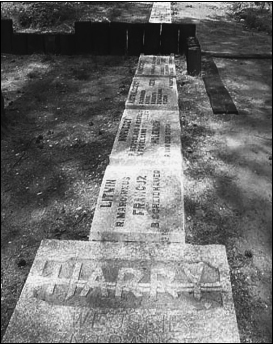

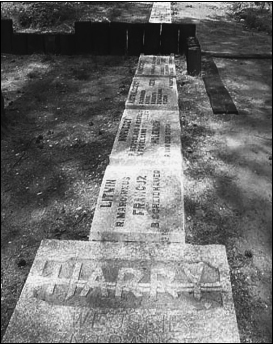

A stone slab now marks the spot to tunnel Harry’s entrance.

The wooden posts at the top of the picture show where the wall to Hut 104 once stood.

The Gestapo took things further on March 4—twenty days before the mass breakout from Stalag Luft III—and issued Aktion Kugel (Operation Bullet), which decreed that recaptured POWs be taken to Mauthausen concentration camp and executed. Prisoners were to be kept in chains for the duration of the journey, and no official record was to be made of their arrival at the camp. Upon reaching their destination, they would be stripped and sent to the “washrooms” in the cellar of the prison building near the crematorium, where they would die by gas or bullet. As with Stufe Römisch III, British and American prisoners were to be handled on an individual basis but held by the Gestapo until a decision could be made. The men at Sagan had been unaware of these ominous developments.

Hitler, presently ranting, ordered that all the Stalag Luft III fugitives be executed upon recapture. The proclamation brought the bickering between his deputies to an end. An example, he said, must be made, an action both punitive and deterrent in its effect. The idea offended no one, but the thought of covering up seventy-six murders posed a considerable challenge. Word of such an atrocity, Göring explained, might leak to the foreign press and result in fierce Allied reprisals. Himmler agreed, prompting Hitler to order that “more than half the escapees” be shot. Random numbers were suggested until Himmler proposed that fifty be executed—a suggestion that met with unanimous approval. Hitler ordered his SS chief to put the plan in motion and assigned to it the highest level of secrecy. The following day—Monday, March 27—Himmler addressed the matter with his second-in-command at the German Central Security Office,* Dr. Ernst Kaltenbrunner. He dictated the content of a secret Teletype, which was transmitted to Gestapo headquarters throughout the country later that same day:

The frequent mass escapes of officer prisoners constitute a real danger to the security of the State. I am disappointed by the inefficient security measures in various prisoner of war camps. The Führer has ordered that as a deterrent, more than half of the escaped officers will be shot. The recaptured officers will be handed over to Department 4 [the Gestapo] for interrogation. After interrogation, the officers will be transferred to their original camps and will be shot on the way. The reason for the shooting will be given as “shot whilst trying to escape” or “shot whilst resisting” so that nothing can be proved at a future date. Prominent persons will be exempted. Their names will be reported to me and my decision will be awaited whether the same course of action will be taken.

The order charged the Kripo with apprehending the Sagan fugitives and selecting who, upon recapture, would be handed over to the Gestapo. Kaltenbrunner delegated the logistics to his two immediate subordinates, Gestapo Chief Heinrich Müller and General Arthur Nebe, national head of the Kripo.

The same day the Sagan order went out, Nebe summoned SS Obersturmbannführer Max Wielen, head of the Kripo in Breslau and the man who sounded the national alarm after the escape, to his Berlin office. Wielen arrived by car at eight-thirty that evening and was ushered in to see his superior. Nebe occupied a ground-floor office at Central Security headquarters. Damage to the building from Allied bombs had forced Nebe to move offices several times in the past year. While the artwork he hung on the walls changed from one office to another, the furnishings—chairs in red leather and a slightly battered settee—remained the same.

“You look tired,” Nebe said, as Wielen entered and observed the familiar furniture. “I’ll order some sandwiches and coffee to buck you up.”

Wielen, surprised to find his chief in a generous mood, took a seat. Nebe picked up a phone and requested the refreshments be brought to his office. When finished, he tapped a typewritten communiqué on his desk. Hitler, he explained, “was very angry” and had ordered more than half the Sagan fugitives be shot. He slid the official order across the desk and allowed Wielen a moment to review it. Nebe made it clear to his subordinate that nothing could be done against a Führer Order. Wielen understood the implication and listened without protest to his assignment. Because most of the escapees had already been captured in the Breslau area, the majority of shootings would take place in Wielen’s jurisdiction. Naturally concerned for his own skin, Wielen said he wanted no official responsibility in the killings. Nebe—who, according to Wielen, “looked extremely tired and was obviously suffering from very severe emotional strain”—said the Gestapo would be assuming full liability. Wielen’s task was to hand over any condemned prisoners in his custody to Dr. Wilhelm Scharpwinkel, Gestapo chief in Breslau, who would assemble the necessary execution squads.

Wielen returned to Breslau on the night train and scheduled a meeting with Scharpwinkel early the next morning. The local Gestapo headquarters sat directly opposite the regional Kripo building. Wielen cared little for Scharpwinkel and the Gestapo in general—not out of any moral indigation, but for the Gestapo’s penchant to view the Criminal Police as an inferior organization. He kept the meeting brief and relayed the order from Berlin. Scharpwinkel seemed pleased with his new responsibility.

“Yes,” he said. “I shall do this personally.”

By Wednesday, March 29, five days after the breakout, thirty-five escapees languished behind bars, four to a cramped cell, in the town jail at Görlitz. Those who remained on the run hoped to make destinations in Czechoslovakia, Spain, Denmark, and Sweden. Luck, however, worked against them. They were seized at checkpoints, betrayed by informants, or simply thwarted by freezing temperatures. Before long, all but three of the Sagan fugitives were back in captivity. That same week, a stack of index cards from the Central Registry of Prisoners of War began appearing on Nebe’s desk. Each individual card contained the name, date of birth, rank, and other personal details of a Sagan escapee. He summoned his assistant, Hans Merten, a forty-two-year-old lawyer, to his office and pointed to the cards.

“You have heard about the Führer Order?” Nebe asked. “Then you know what to do. Müller, Kaltenbrunner, and I are lunching together. I will take them a list of men to be shot when I see them at lunchtime.” Nebe shoveled some cards across the desk. “Have a look to see whether they have wives or children.”

Merten did as instructed and returned the sorted cards to Nebe, who shuffled the deck and began flipping through them one by one, pausing momentarily to read the short biographical sketch of each man.

“He is so young,” Nebe muttered, staring at one card. “No!”

He placed the card upside down on his desktop and picked up another.

“He is for it!” he said, slapping the card down.

This process continued for some time, until Nebe had two separate piles of cards on his desk, one larger than the other. He stared momentarily at both stacks, swapped one card for another, and at last seemed satisfied with his work. He handed the larger stack to Merten.

“Now, quickly,” he ordered, “the list!”

Merten took the cards to Nebe’s secretary and read her the list of names. He deliberately misstated the location where some prisoners were being held, in the vain hope that orders of execution would be misdirected. The “mistake,” however, was noticed before the orders were sent down the wire. Nebe promptly dismissed Merten and sent him off to teach criminology at a school in Fürstenberg. It was, all things considered, a merciful decision—but Nebe’s magnanimity did not extend beyond his office. He had a list of fifty names and an order to obey.

The killings began on Wednesday, March 29.

*Otherwise known as the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA).