Letter 6 Professional Engineering Status: Societies, Certifications, Designations

Dear Natasha and Nick,

Greetings to you from my office. I’m looking at the various engineering books that surround me. Let’s assume in an ideal world that I know everything in them perfectly. And that I even have the highest possible academic training with a doctoral degree in engineering. Those facts would still not always legally qualify me to be an engineer who can authorize the fabrication of devices, the construction of structures, etc., especially when public health and safety are affected.

So, I’d still need a professional engineering society (PES) that’s legally authorized by the government to certify and designate me as a professional engineer (PE), or something similar. And, that’s what this letter is about, namely, the functions, benefits, and drawbacks of professional engineering societies, certifications, and designations. Now, keep in mind that the details of what I write below may vary from country to country and PES to PES, but this letter should still give you an accurate appreciation of this topic. With that stated, let’s get to it.

What’s the History of the PES?

During ancient and medieval times, groups of skilled craftsmen or tradesmen—the forerunners of today’s engineers—would often organize themselves into trade guilds or associations. Sometimes, the guilds acted like mutual support groups that provided moral and material assistance to its members. At other times, the guilds were more like political lobby groups or labor unions who advocated with the government for the rights and rewards of its members. In other instances, the guilds were exclusive clubs that focused on the job security of members by ensuring that non-members could not legally offer similar competing services to the public.

Much later in France, formal professional societies were created for military engineers in 1690 and civil engineers in 1716, which was followed by the establishment of a training school for civil engineers in 1747. In Britain, an informal Society of Engineers was established in 1771 that met over meals to discuss solutions to various engineering problems. Then, in the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution (1769–1829), formal professional societies were organized in Britain for civil engineers (1828), mechanical engineers (1847), electrical engineers (1871), and, sometime even later, chemical engineers (1922).

Then, as reported by S.H. Christensen and colleagues in their book Engineering Identities, Epistemologies and Values (Springer, 2015) an important meeting occurred in 1960 called the Conference of Engineering Societies of Western Europe and the United States of America. The conference declared that “a professional engineer is competent by virtue of his/her fundamental education and training to apply the scientific method and outlook to the analysis and solution of engineering problems…In due time, he/she will be able to give authoritative technical advice and to assume responsibility for the direction of important tasks in his/her branch.” (p. 157–158). The legacy of these early trade guilds and engineering societies carries down to our own day.

What’s a Modern-day PES?

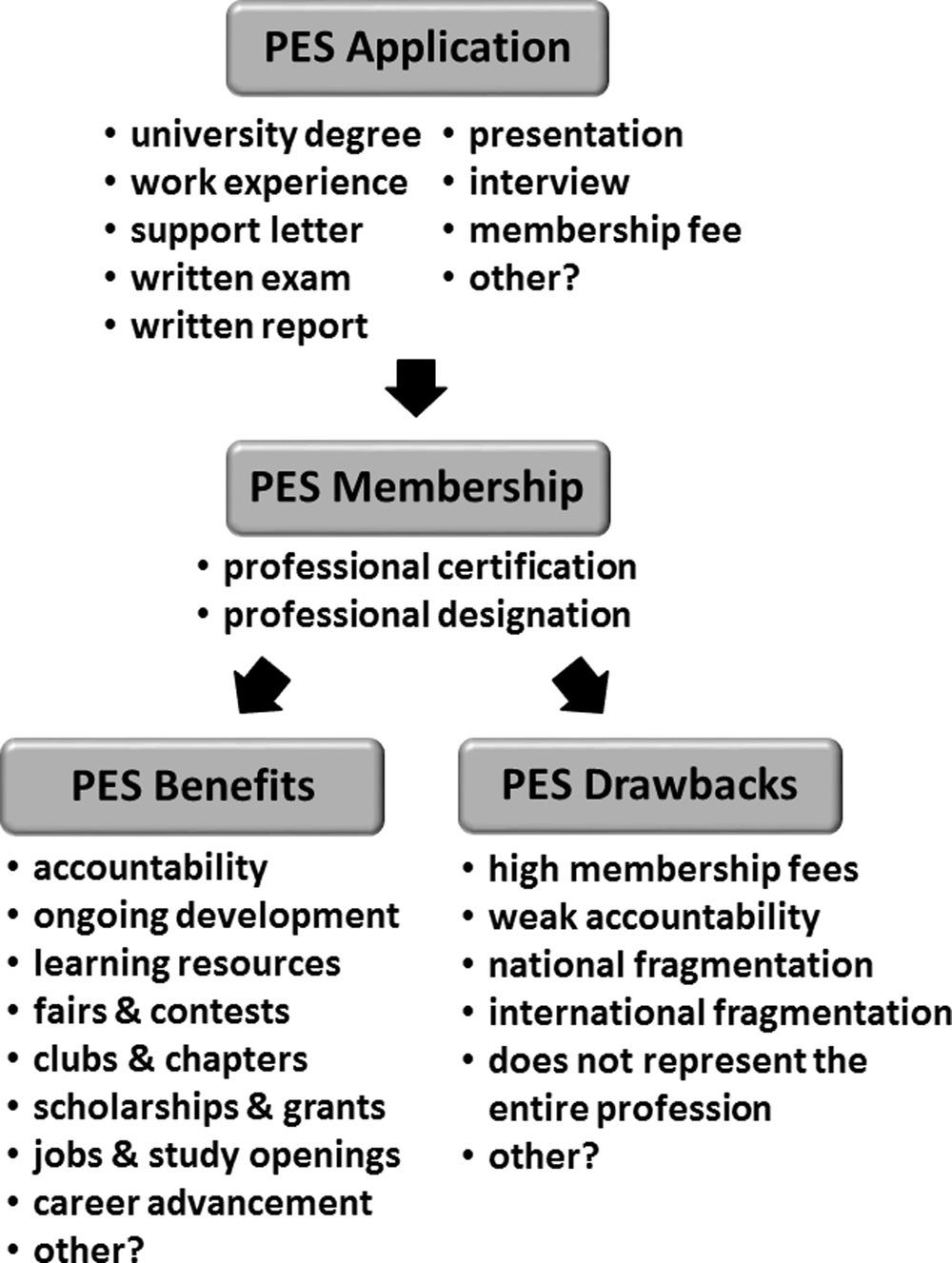

Today’s PES is a formal organization that is recognized by a regional or national government and, thus, has the authority to confer, withhold, or remove the status of PE to an engineer employed in university, industry, or government (see Figure 6.1). Don’t confuse a PES with the many other scientific or engineering organizations that an engineer can also join that may be related to their work, but these groups do not have any legal authority to confer PE status on anyone.

Figure 6.1 The functions, pros, and cons of a professional engineering society (PES).

A PES mainly exists to give formal certification to members who have the proper education, experience, competence, and ethics to do engineering work that is high quality, reliable, safe, and honest. Senior or supervising engineers in industry or government, as well as professors of engineering at the university, are often required by their employers to be formally certified. But, others get certified because it can be a strategic career move in the long-term, not because they are required to do so.

In any case, certified members then may be given official designatory letters they can add after their name to visibly assure the government and the public they are qualified experts who can do the job. These are the letters PE that I’ve already been using here, or it may instead be PEng (professional engineer), CEng (chartered engineer), or something similar, to indicate professional certification. And, it may or may not include additional letters like A (affiliate), M (member), or F (fellow), or something similar, that are attached to the acronym for the official name of the PES to indicate membership.

So, for example, let’s consider an engineer who has the post-name designatory letters PhD, CEng, MIMechE. The PhD signifies their university education as a doctor of engineering, the CEng signifies their official certification as a chartered engineer, and the MIMechE signifies they are a member of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Or, let’s assume an engineer has the post-name designatory letters BASc, PE. The BASc signifies their university education as a bachelor of applied science and the PE signifies their official certification as a professional engineer, but in this case the particular PES does not offer designatory letters to indicate the engineer’s membership in the PES.

Why and How Do You Join a PES?

In many cases, employers require PE status for their senior or supervising engineers in industry or government, or professors of engineering who teach and do research at a university. Obviously, these folks have no choice, since getting PE status is a condition of their employment. In other cases, junior engineers, research engineers, and others, may not be required by their employers to do so, but they decide to get certified anyway because it can help them increase their salary, promote them to a higher position, improve their resumé for future job applications, etc.

If you need or want PE status, you may need to satisfy one or more of these requirements. You’ll definitely need a bachelor’s (BE), master’s (ME), or doctoral (PhD) degree in engineering—with these or other equivalent designatory letters—from a university or technical school. You may need one to several years of practical work experience. An engineer with PE status who’s worked with you may need to vouch for your competence and honesty via a support letter, email, etc. There could be an exam in engineering ethics, engineering law, etc., that needs to be passed. You may be asked to submit a written report or give an in-person or online presentation summarizing your career-to-date to show your engineering ability, as well as describing your long-term career goals to show your commitment to lifelong learning. You might be interviewed by a committee from the PES. There’s probably a one-time application fee and/or an ongoing membership fee. And there could even be other requirements that I haven’t listed here.

Now, if you don’t require PE status and have no great career ambitions, then carry on as you are without giving it a second thought. But, if you need or want PE status, then it’s probably best to keep it active for the rest of your career because of the advantages discussed earlier. If you resign or let your PE status expire, it may not always be quick or easy to get back again, if a circumstance arises in which you need it.

What Are the Benefits of a PES?

In addition to giving an engineer a legally recognized PE certification and designation, a typical PES may offer a variety of extra advantages and opportunities to its members. I list some of the key ones, but there may be others.

A PES can provide accountability. Membership in a PES is a gentle encouragement and, at times, a stark reminder to the engineer about their responsibility to do high-quality, reliable, safe, and honest work. If a PE is accused of being incompetent or unethical, a PES can temporarily suspend the PE status. If the engineer remains employed, they will likely need to work under the direct supervision of another PE. If the accusations of dishonesty or incompetence are eventually proved false and/or the engineer has undergone sufficient retraining, their PE status may be restored. If not, the PE status can be permanently removed.

A PES may encourage ongoing development. Just because an engineer has PE status, of course, that doesn’t mean that they have nothing new to learn through in-person or online events and resources. There are always new scientific discoveries, emerging technologies, changing government regulations, personal organization skills, leadership skills, communication skills, entrepreneurial skills, and so forth, that they can learn about in order to make them more efficient and effective in their work.

A PES might provide learning resources. This allows members to have free or low-cost access to physical or digital scholarly journals, trade magazines, and newsletters, so members can keep up with the latest scientific findings, technological changes, industry developments, and government policies. Access to university textbooks, reference works, biographies, histories, etc., can provide foundational technical and other information. And, online software can help members with 3D drawing, computational analysis, etc.

A PES will sometimes organize science and technology fairs and contests. Student and full members of the PES can give short presentations, create physical displays that highlight their work, or enter their own inventions in competitions against other participants. These events are a way of reaching out to the general public, gaining the interest of potential private donors and industry sponsors, allowing attendees to network with each other, and recruiting new members to the PES.

A PES might sponsor local clubs and chapters. These could be focused on student members who are still studying at university, or working engineers in university, industry, or government. Either way, clubs and chapters provide great opportunities for growing an engineer’s personal network of contacts that can open up doors of opportunity in the future. Such clubs and chapters often host events with guest speakers, discussions, fundraising, meals, and so forth.

A PES could award scholarships and grants. This can help financially support student members to complete their BE degrees at university and full members who are pursuing an ME or PhD degree in engineering. Moreover, funding can greatly aid members who are working on research projects in university, industry, or government. And, such funds can be used to cover the travel expenses of members going to academic, industry, or government conferences.

A PES can advertize new jobs and study opportunities. This mainly occurs through emails, physical or digital newsletters, or postings on their website. Such information is critical for various people, such as new engineering graduates seeking full-time employment. Or, it could be relevant to those who’ve just graduated with their initial BE degree, as well as working engineers, who now wish to pursue an ME or PhD degree in engineering. Or, it may be useful for working engineers who are looking for a new job.

A PES may help with career advancement. Junior engineers just entering the workforce, engineers engaged mainly in pure research, and others, are often not required by law or their employers to obtain PE status. And so, many engineers in these situations choose not to join a PES or get PE certification because it doesn’t benefit them. However, there are others in the same situation who still choose to join a PES so they can be a certified PE. The reason is that it opens up new possibilities, such as a salary increase, a job promotion to a more senior position, a better resumé that is more attractive to future employers, etc.

What Are the Drawbacks of a PES?

A PES, like any organization, can have shortcomings. There is an adage that says something like, “The tail wags the dog.” This means that someone or something that is originally meant only to offer assistance, if one is not careful, can eventually take over total control and seek only its own benefits. So, although a PES is officially meant to certify, designate, support, and oversee its engineering members, it can potentially become a rigid and decayed system that has forgotten its original purpose. Below, I discuss some of the most important drawbacks, but there could be others.

Members typically have to pay rather high membership fees. This is often required to obtain and/or maintain PE status, but sometimes these fees are too high for the few benefits that members actually get in return. To be fair, some employers are willing to reimburse their engineers for these costs. Even so, that’s why some engineers who don’t really need to be a PE for their particular work may refuse to ever get one. Other engineers will criticize the PES as simply being a scam to get money to keep itself running, although it doesn’t really have any true value to them on a day-to-day basis.

Another common problem is weak accountability. A PES is supposed to keep its members accountable to ensure they are doing their duties ethically and giving products and services to customers that are high-caliber, reliable, and safe. Sadly, a typical PES may have absolutely no idea what its own members are doing, since it doesn’t require a regular progress report from its members via in-person interview, written report, email, telephone, video, and so forth. And, conversely, a PES may not even send any regular communications to its members, other than a reminder to pay the annual membership fees.

On top of that, there’s the challenge of national fragmentation. This means that some countries, especially large ones, have a different PES for each region of their country. The reason for this is the existence of slightly different laws from region to region. Even so, the government and each PES are creating barriers for a PE to work in different regions of their own country. The PE may have to rewrite a certification exam or redo an interview each time they move, which is often a waste of time, energy, and money. So, whenever possible, in my view, it’s better to have one single PES—either for each engineering specialty or combined together—that manages all engineers in the whole country.

Similarly, there’s the issue of international fragmentation. This is more understandable, since each country has its own distinct laws that the PES must follow. But, there’s a great irony here. One country might have a PES with only loose requirements for conferring PE status to its engineers, yet it won’t officially accept the validity of PE status from another country whose PES has much higher requirements. Also, a PES may totally reject an immigrant engineer and ask them to go back to university to get another engineering degree. Such re-education is a huge barrier that may be too large for some people either financially or psychologically, which means another potentially talented engineer is being lost. So, in my view, it’s better to have a more realistic pathway for an immigrant engineer to transfer their PE status to the new country. For instance, the immigrant engineer could demonstrate their professional competency by passing a few equivalency exams and/or interviews, as well as getting some practical experience.

Finally, a PES doesn’t fully represent the engineering profession. As mentioned already, a senior or supervising engineer or a professor of engineering at a university is often required by their employers to be members of a PES and obtain PE status. Yet, there are others who don’t need PE status, but get certified anyway because they think it’s strategic for their long-term career plans. But, of course, this doesn’t represent all the many engineers that are not required to do so and, thus, don’t obtain PE status. Their ideas and dreams are not represented by a PES, and their ethics and competence are not monitored by a PES. This can turn out to be a big problem in the far future for the profession of engineering as a whole.

So, What’s the “Take Home” Message of This Letter?

My intention was not to persuade you one way or another about joining a PES and getting PE status. So, I’ve done my level best to outline the main pros and cons. I’ll remind you again that what I’ve written will not exactly apply to every context, since it can vary from one country to another and from one PES to another. Having said that, I’ll bid you farewell for now, having every confidence that you’ll make the right decisions for your engineering career.

Seize the day,

R.Z.