Letter 13 Start Your Engineering Career: How to Get a Good Job

Dear Nick and Natasha,

I feel fortunate that I can spend time thinking about your questions on engineering as a career. To be frank, this process has at times challenged me to re-evaluate my own attitudes and actions, which can be mildly uncomfortable. But, mostly it’s been a real pleasure to engage the topic. In this dispatch, the perennial problem of how to acquire a good engineering job is the subject of inquiry. There are probably as many different approaches to this as there are grains of sand on the beach. Every gainfully employed engineer has their own story about the path they traveled to find their job. However, many of these stories have things in common, which will be my focus here. Much of this content is based on my own experiences, the experiences of my colleagues, and the various resources created by experts in finding a job.

Also, because some of this job search advice may seem generic and applicable to any field of endeavor, I’m going to sprinkle in some examples from my own engineering career, so it will be more relevant to you. Now, I don’t claim that if someone reads this letter and puts everything into practice that this will guarantee them success in finding an engineering job. Yet, I believe and hope that the ideas here can help, at the very least, to hone a person’s job hunting skills and strategy. A major caveat, of course, is that there are many things that are often beyond our control that could influence our ability to get a good job, like global economic changes, national political circumstances, regional ecological upheaval, company bankruptcies, personal health crises, and so forth. With that said, let’s get to it.

What’s Your Engineering Dream Job?

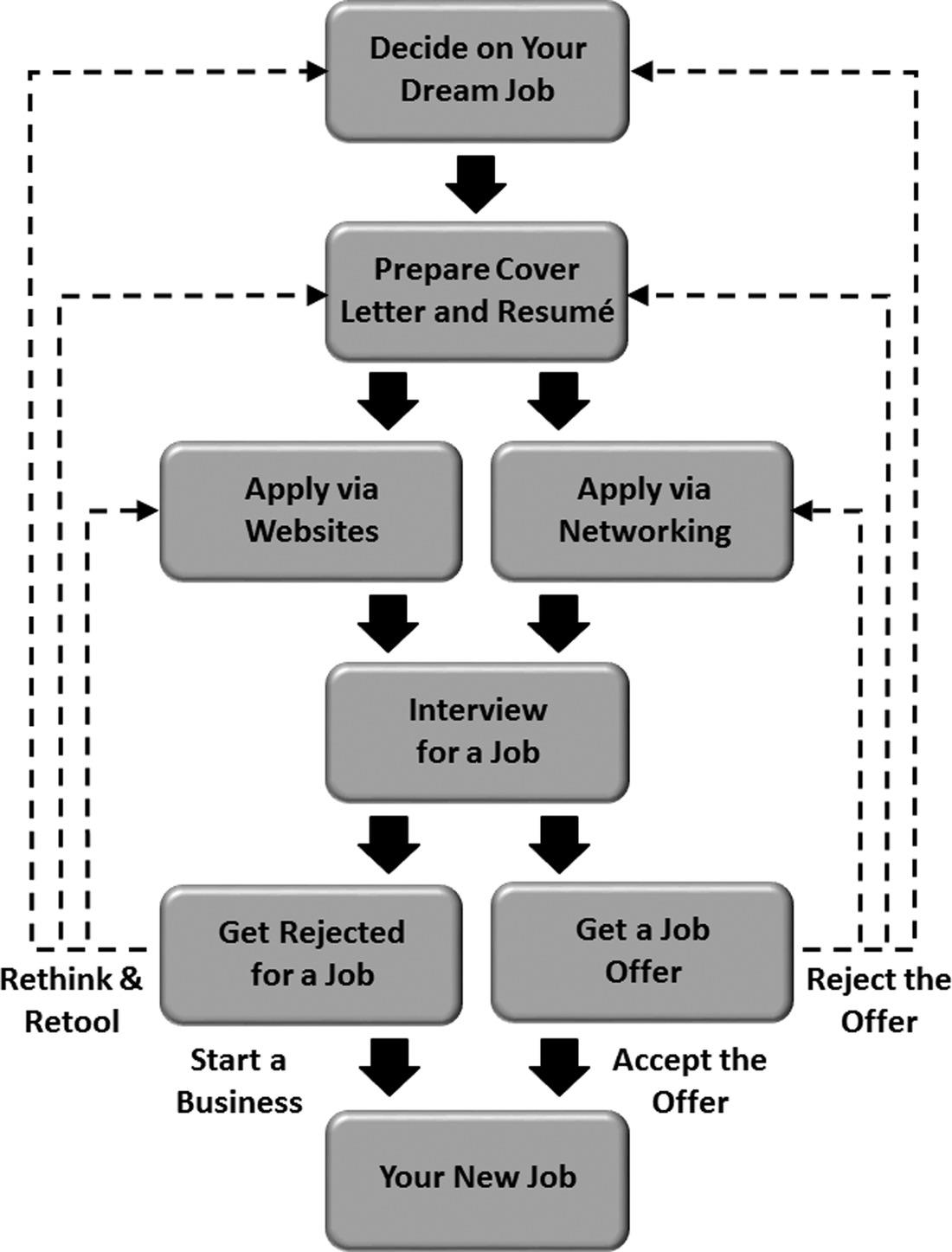

This is the first and most important question to ask because the rest of the job search process flows after it (see Figure 13.1). Why settle for something subpar, when you can have the best? Everybody’s idea of a dream job is going to be different, based on their personality, circumstances, family commitments, stage in life, worldview, and a whole host of other things that are too numerous to list here. And, of course, a person’s concept of their ideal job may actually change over time. So, take some time to think about what it is you really want and what factors need to be considered. Write down your ideas, or even record your thoughts on audio or video. What are important factors that would describe your perfect engineering job? Here are some possible criteria to reflect upon, but I’m sure there are others.

Figure 13.1 Searching for an engineering job.

Work duties. Are there particular tasks, techniques, and technologies with which you have a lot of experience and/or that would suit you best? Do you have any health and safety concerns about the job?

Work terms. Are you looking for full-time or part-time hours, and would a lot of overtime hours be acceptable? Would a limited contract be okay, or will you only accept a permanent position?

Financial benefits. What kind of base salary, extra benefits, and retirement package are you looking for? What is a typical salary for someone with your level of education and experience?

Employer type. Do you want to work in a small company, which may have a more relaxed atmosphere but offers limited advancement opportunities? Or would a large corporation be preferred, which may have a fast-paced atmosphere, although it may have more chances for promotion? Is it a relatively new and inexperienced company, or is it an old and well-established organization?

Geography. What towns, cities, or countries would you be willing to work in? Have you considered the weather conditions, political situations, cultural practices, or commercial amenities in that location? Do you have any friends or family that already live there?

Social aspects. Do you have any family, friends, or dependents that your decision might affect positively or negatively? Should they be involved in your decision-making process?

Personal advice. Is there anyone you know whose advice you can get who has a similar kind of job, who works in that company, who lives in that city, or who has comparable family circumstances?

Writing a Cover Letter and Resumé

A typical engineering job opening will often attract dozens and sometimes hundreds of applicants. As such, the employer or hiring team will get swamped with many cover letters and resumés that they’ll initially just skim over briefly to exclude weak applications. Then, they’ll probably carefully read the cover letters and resumés only of those on the short list of applicants who are more seriously being considered for the job. Some employers, especially universities that are hiring engineering professors, will require additional information in the application package, such as sample academic publications, a teaching statement, a research statement, etc. So, you as the job applicant need to accomplish 2 important things in the application. You should show your uniqueness—in a positive way, of course—from all other job seekers. Then, you should try to persuade the employer that your education, experience, knowledge, and skill are the best match for what the employer wants and needs. Remember that your cover letter and resumé may need to be slightly adjusted for each specific job application. Here are some tips on cover letters and resumés.

Cover Letter

A good cover letter is very important. You’re introducing yourself and your application. Employers will usually read this before your resumé or any supplemental documents. Here are my top 10 tips.

- Keep it short. A cover letter should be 1 page maximum for industry or government job applications, or at most 2 pages for university professor jobs.

- Make the greeting specific. The opening salutation should address a specific person by name and formal title, if you know it. Otherwise, you will need to greet the search or hiring committee.

- State your objective. In the first line, state clearly for which particular job you are applying. Don’t say you’re applying for any job that’s available, since it looks like you’re not sure what you want.

- Write a catchy next line. Indicate you’re applying because you’re the best candidate for that specific job. Then proceed to explain the exact reasons why this is the case, such as how your education, experience, qualifications, skills, etc., match the specific job profile.

- Use formal and professional language. Don’t write “I’ve” but “I have.” Try to stay away from using slang expressions or idioms. It’s also best not to attempt any humor in the letter.

- Make sure the letter is clear, concise, and positive. Keep your sentences crisp and reasonably short. Try to avoid complaining about your prior workplace or about your bad current financial situation.

- Use bold or italic type for keywords and phrases. Do this sparingly for specific things that you want to highlight, so the letter visually appears to have a logical structure.

- Remember the details. Don’t forget to add the date, the recipient’s name, title, and contact information at the top, your full contact information, and your signature.

- Double-check the letter. Make sure the spelling, grammar, font size (11 or 12 is typical), and page margins (1 inch is typical) are correct.

- Get some feedback. Let a trusted friend or colleague read it and give constructive criticism. Get professional help from a job search agency or coach, if possible.

Resumé or CV

Your resumé or CV (i.e., curriculum vitae) summarizes your educational qualifications and professional experience. This is the core of your application. The employer will probably go through this in some detail. So, it deserves a lot of attention. Here are my top 10 tips.

- Keep it short. Make the resumé 2–5 pages maximum, unless the employer asks for your full resumé. But, for an engineering job as a university professor, senior industry position, or government researcher, it is quite common to submit a full resumé which can be dozens of pages long. Thus, it might be a good idea to always keep an up-to-date version of a short and long resumé.

- Identify yourself. State your name, educational degrees, current occupation (if you have one), and contact information at the very top of the first page.

- Identify your goal. Give a strong and specific statement near the start about your career goal, tailoring it to the particular employer and job opening.

- Summarize your career. Use the rest of the first page to summarize your education, work experience, and special skills that are really relevant to the particular job you’re applying for. If possible, state them in the order they will appear in the rest of the resumé, almost like a book’s table of contents.

- Give the details. Use the rest of the resumé to provide the details of your education, work experience, teaching experience, special skills, publications, patents, awards, achievements, citizenship, etc. And also include some professional references at the end, such as prior employers, professors, or work colleagues who can vouch for what a great engineer you are; make sure to get their permission to list them.

- Keep it neutral. Don’t put any information in your resumé that could potentially bias people against you. The truth is that we all have conscious or unconscious biases, including employers. You don’t want them to reject you too quickly. So, I suggest you avoid including your age, gender, height, weight, photo, languages (unless relevant to the job), political affiliation, race, religion, etc.

- Make it easy to read. Whenever possible, use bullet points and lists. This will make it easier for the employer to read. The last thing they want to do is read long sentences and essays.

- Make it look good. For each major section of your resumé, use bold or larger font for the title. Don’t be afraid to introduce color, such as a thin blue line that runs across the top or side of each page.

- Double-check it. Ensure there are no spelling or grammar mistakes, and that the font size (11 or 12 is typical) and page margins (1 inch is typical) are appropriate.

- Get some feedback. Ask one of your friends or colleagues to give you their opinion on your resumé. If needed, a professional job search agency or coach can be very helpful.

So, for example, as someone who’s been involved in hiring biomedical engineering students and junior biomedical engineers, I can describe what I’ve looked for when I’ve reviewed cover letters and resumés. My main goal is to arrive at a shortlist of serious potential applicants, by excluding applications that are clearly not suitable as quickly as possible. Despite my best efforts in accurately describing the qualifications and duties in the job profiles that I’ve posted online, unqualified people have still sent me applications. The first step is to exclude those who are not qualified, such as those who don’t have an educational background in engineering (e.g., physics or biology or medical graduates) and those who don’t have the proper set of skills (e.g., no experience in computational modeling, mechanical stress testing, or fabrication techniques). The next step is to exclude those who have too many spelling and grammar errors or whose application is very disorganized. The reason is that writing skills are important for producing grant applications, thesis dissertations, progress reports, and journal articles. The final step is to exclude those whose last job was in a very senior engineering role, but who are now applying to me for a very junior engineering role; unless there is a really good reason for this, it makes me wonder whether that person left their prior job for dubious reasons. This process usually helps exclude about 75% of applications, while the remaining 25% of applications are closely scrutinized and compared to each other based on job qualifications and duties in order to arrive at a final shortlist of applicants I will interview.

Applying for Jobs via Websites

Back in the “old days” people would often look for work by scouring job ads and classified sections of the newspaper. Some things have changed, but others haven’t. These days, the equivalent of the newspaper is probably the internet. The problem is that the internet is so huge that it can be intimidating and, in fact, it may be hard to know exactly where to start. The plus side of this is that there are many websites out there that you can explore to find out what job openings exist. Because engineers are mostly employed by the university, industry, and government, those websites are probably the best place to begin, but there are other databases that should be explored.

I want to also briefly mention some things you probably should not do that would be a waste of your time and the employer’s time. Don’t apply if you are really not qualified for the job. Don’t apply to an employer who doesn’t have a job opening. Don’t apply if you know the employer is hiring someone from within their organization, unless of course that includes you. Don’t repeatedly contact the employer to see how the application process is going, especially if they clearly state in the job description that only suitable applicants will be contacted. Now, here are some suggestions for where to look and apply for jobs.

University websites. This is the best place to start looking for a position as an engineering professor, lecturer, researcher, or technical officer. Some universities have centralized job databases that you can explore and apply through, whereas others let the individual departments handle this. The same can be said for technical schools and community colleges.

Industry websites. This is a good place to start if you are looking for a position as an R&D, operations, production, maintenance, or sales engineer, or perhaps a role in management. Often, you can directly interact with the president or upper management of a small engineering business or organization, but you will often directly communicate with the HR (human resources) department for larger engineering companies or organizations. Make sure to double-check if they have branch offices, since the job opportunities may vary from branch office to branch office.

Government websites. Local, regional, or national government websites often have job databases that you can search for a variety of engineering jobs that are similar to the ones offered in industry. Also, you will probably be dealing with the HR departments directly, rather than the people with whom you would actually be working. Sometimes you can be automatically informed of new job openings by joining their email list, if they have one.

Professional engineering society websites. One of the advantages of being an official member of a recognized professional engineering society for a certain specialty (e.g., aerospace, civil, electrical, mechanical, software, etc.) is that they often provide information on job openings and even offer to help you find employment. But, they may not offer such services to non-members. Sometimes you can be automatically informed of new job openings by joining their email list, if they have one.

Research network websites. University engineering professors and other research engineers primarily join such online groups to exchange data, ideas, and journal articles with their peers. However, another benefit is that some of these groups provide lists of job opportunities, or at the very least you are able to post a message asking if anyone knows of a job opening. Sometimes you can be automatically informed of new job openings by joining their email list, if they have one.

General job websites. These extremely popular websites are probably the most common way that people look for gainful employment and that employers advertise their job openings. These websites let you input keywords to help narrow the search, such as engineering specialty, geographic location, salary range, and so on. They are usually free to use for general purpose job hunting, although some may require a fee for advanced services like reviewing your resumé or coaching you before an interview. Usually, you can be automatically informed of new job openings by joining their email list.

Social media websites. Professionally oriented websites often require you to be a member to formally search for job openings, although as a member you can also informally ask your “friends” or “contacts” if they know of any opportunities. Socially oriented websites may not have job search capabilities, but you can also make informal inquiries of your “friends” or “contacts” about engineering jobs.

Independent email lists. You can also join an engineering email list that sends you regular updates on general topics of interest, upcoming academic or industry conferences, and job openings in university, industry, or government. These are often run by volunteers as a service to their peers, rather than run by universities, industry, government, or professional engineering societies.

Recruiting agencies. Some engineering companies hire recruiting agencies to do the initial task of evaluating the many job applications they receive and/or directly contacting potential new employees who may, in fact, already be working at another engineering company. The agency whittles down potential new employees to a shortlist of the best candidates, which they pass on to the engineering company. So, the engineering company doesn’t have any direct contact with you until you do a formal job interview. Also, if you do get a job this way, it’s possible that it may only be a contract job for a limited period of time, thus, it often has a lower salary, fewer benefits, and no job security. But, if you perform well and the company has an opening, then the contract job could be converted into a full-time permanent job.

To illustrate the point, I was once in charge of seeking out and hiring a junior engineer who could run the daily operations of my team’s biomedical engineering research lab. I wrote a simple 1-page job profile, got it approved by my colleagues on the team, and then proceeded to upload it to a well-known general job website and an independent email list. This did not cost me anything. I did not do any other advertising of the job. To my surprise, within about 2 weeks, I received almost 120 applications from all over the globe by email. And, from this group, a suitable person was eventually hired. This highlighted 2 things in my mind. First, engineering employers can widely advertise their jobs by making strategic use of websites with minimal time, effort, and cost. Second, engineers looking for a job through website searches should know that the job market is highly competitive with many people applying for the same position, so they need to make sure they stand out from the crowd (in a good way, of course).

Applying for Jobs via Networking

Back in the “old days,” job seekers often asked their friends and acquaintances to recommend them to their boss. There was some wisdom in this. And the truth is, social networking is probably still one of the most effective methods for landing a job.

There is good scientific evidence for this based on “social network theory.” In essence, the entire world is like one huge social network composed of a vast array of interlocking networks of networks, some small and some large. This entire global social network is held together by “super connector” individuals who have the largest number of links to other individuals and networks. It is these “super connectors” that are the most useful to us in finding a job by referral. In other words, don’t only look to your family or closest friends for help finding a job, since they probably run in the same or similar social circles that you do. Rather, mainly look to those people in your social network that may be “super connectors” because they have access to people you don’t, even if they are merely distant acquaintances you rarely communicate with. So, the friend of a friend of a friend, may actually be the best person to help you find a job.

Another way of thinking about this is through the 80/20 rule (also called Pareto’s Principle), which also has established scientific evidence for it. It states that about 80% of your successful results come from about 20% of the things you spend your time, effort, and resources on. So, this means that only about 20% of your social contacts will actually be practically useful to you in finding a job, while the other 80% of your social contacts will be ineffective. If used wisely and deliberately, it is these social networking efforts that can potentially help you get a volunteer position, an internship, a part-time job, a contract job, or even a full-time permanent job as an engineer. But, you’ll probably still need to give your cover letter and resumé to your potential employer, and then do an interview before you officially get the job.

As an engineer, you may be interested to know that these social networks can be modeled and predicted mathematically using the power law. Simply put, the power law is N = anb where N is the number of social links that a particular person has, n is the number of people that also have N social links, and a and b are fixed numerical constants that are unique to that social network. This can also be applied to other manmade and natural networks like ecosystems, chemical interactions, brain cell connections, website linkages, etc.

For instance, when I did my PhD (i.e., doctoral) degree and post-doctoral fellowship in mechanical/biomedical engineering, I met a lot of professors and fellow master’s and PhD students at university. After graduating, over the next few years, I kept in touch with some of them occasionally, but most weren’t close personal friends. At that time, I was really struggling to earn a living through a few short-lived contracts for medical writing and some part-time lecturing at another university. Unknown to me, one of my prior university acquaintances landed a full-time permanent engineering job running a biomedical engineering research lab in a large urban hospital in a nearby city. This person was also putting the finishing touches on their master’s degree. Their supervising professor—who also supervised me for my PhD studies—suggested they contact me to provide some feedback on their master’s dissertation. So, we met a few times to discuss their master’s topic. Then, this engineer asked if I’d be interested in volunteering at their research lab; I said yes without hesitation. After a few weeks, amazingly, this turned into a part-time contract job for me. A few weeks later, this engineer told me they were soon going to quit their job to take another job in another country, and then they asked if I’d be interested in replacing them on a full-time permanent basis; I quickly said yes. After providing my resumé and doing a formal interview with the boss, 3 months later I was the full-time permanent manager of that same biomedical engineering research lab. All this happened because of the power of social networking!

Interviewing for an Engineering Job

This is probably something that most job hunters don’t like to do. Whether it’s by telephone, video conferencing, or in-person, it can be intimidating. And it feels like we’re being judged and evaluated which, of course, we are. Now, some people are naturally shy and nervous, and others are naturally gregarious and carefree. But, one type of personality will not necessarily do better than another in an interview, although this can be a factor. Rather, I think good preparation beforehand is just as, if not more, important. So, here are some practical tips to keep in mind.

Know the format. Is it going to occur by telephone, internet, or in-person? If it’s by telephone, then especially make sure you have some water close by to keep your voice lubricated. If it’s by video, then especially make sure your appearance is optimal in grooming and apparel, the camera shows your whole face, and the background behind you looks neat and professional. If it’s in-person, then especially make sure your grooming and apparel are appropriate, your body language is relaxed but formal, that you don’t make any annoying gestures over and over again, and that you’re not wearing strong soaps, perfumes, or colognes that can be distracting. An interview is not the time to experiment with fragrances and fashions.

Know the time and place. If possible a few days before an in-person interview, take a trip to the actual location, and even room, where it will occur. This will help you know exactly how long it takes to get there in order to arrive on time for the interview. And, this will help you know the atmosphere of the room in order to anticipate elements like lighting level, noise level, room temperature, washroom location, etc.

Practice your answers. Write down any questions that you might be asked by the employer, as well as your best possible answers. Then, practice giving your answers out loud, to make sure they are clear, concise, and honest. Maybe do a practice session with a friend or colleague, to make sure you answer the questions well and make any adjustments if needed. Obviously, if you are expected to give a short presentation to the employer, make sure to follow any formatting requirements and have some time to practice a lot beforehand, perhaps even getting a friend or colleague’s feedback.

Practice your questions. Similarly, write down any questions you have for the employer. Almost always, they will give you a chance in the interview to ask them something. I recommend at most 2 or maybe 3 questions. Make one of the questions philosophical, such as how the employer describes the vision of the company or why this particular job has become available; this shows you want to understand the big picture. Make one of the questions practical, such as the amount of salary or the number of people who will be on your team; this shows you are a hands-on person too.

Talk only 50% of the time. From my experience and from what the experts have said, the best interviews are those in which the employer and the job applicant engage in a real dialogue. Each of them only talks about 50% of the time. So, if you have a tendency to either talk too little or talk too much, then please be careful about this and adjust things accordingly in the interview.

Bring your notes. If possible and appropriate, bring a small notepad, file folder, 3-ring binder, or electronic device which has your cover letter, resumé, practice answers, and practice questions. The employer may want to ask you something specific about your cover letter or resumé, so you want to appear prepared by quickly referring to your own copy. Also, a quick glance at your practice answers and questions can trigger your memory, so you can talk effectively when it’s your turn.

Relax, you’re the expert on “you.” Remember that most of the interview is going to involve the employer asking questions about your experience, education, knowledge, skill, and so on. Who knows more about you than you? You are the real expert on you. The employer can’t possibly ask you a question about you that you don’t already know. So, relax.

Take a break the day before. If possible, take a break from preparing for the interview the day before the interview. Don’t be over-prepared so much that you become tired, confused, or nervous. A string stretched too tightly will eventually snap. I suggest you do something relaxing and fun the day before to take your mind off the interview.

Say thank you afterward. Of course, right after the interview, thank the employer for their time and effort, as well as giving you the opportunity to apply. That’s common sense. But, it’s expected and appropriate to send another very brief thank you a few days after the interview. It will remind the employer about you. And, it shows you are really interested in the job. But, I recommend doing this only by email, since a telephone call, video message, or in-person visit may seem too intrusive.

At this point, I’d like to share my experience as a senior research engineer in hiring junior engineers, master’s or PhD students, or post-doctoral fellows for biomedical engineering jobs. I want to give you an idea of what a typical engineering job interview might involve. I usually do a focused 30 minute telephone, internet, or in-person interview of the applicant. I start by thanking them for their interest and application. Then, I briefly describe the job duties, the workplace facilities, the other people they will work with, the salary and benefits, and the approximate timeline within which a hiring decision will be made. I also remind them there are other applicants being interviewed for the same job. Next, I ask a series of specific questions to see if they are really suitable for the job: why they are applying to this specific job; what experience they have with fabrication machinery; if they’ve done CAD and other computer modeling; what data analysis software they’ve used; what experience they have with mechanical stress testing; and if they have any concerns about working with biological specimens. I also want to know about their legal status in the country to determine if there will be any obstacles to hiring them. Of course, I make written notes to myself as we go through the interview. Then, I give them a chance to ask questions about the job. And, finally, we say our cordial goodbyes and end the interview. After the interview, I enter a numerical score for each response to each of my questions—as well as a score for their sincerity, reliability, maturity, and communication skills—in a large table that I use to compare the shortlist of applicants for the job.

Getting Rejected for an Engineering Job

Rejection never feels good. That’s just our human psychology. But, it’s part of the process of looking for an engineering job. So, don’t take it too personally, and don’t let it be too discouraging. Keep focused on your goal. There may be a whole host of reasons why you, along with probably many others, were rejected for that particular job. Remember, there could be tens or hundreds of other people who apply for the exact same job. Many of the reasons for rejection are beyond your control, while some reasons could be areas you can improve upon.

First, there may be other applicants with better skills, knowledge, and experience for that specific job, or who have a superior ability during interviews. Second, maybe the employer checked your other social media profiles and found something they didn’t like about you; so, always be careful what personal information and photos you post online. Third, the employer may have already had a specific individual in mind that they planned to hire long before, but they were legally obligated to advertise a job opening because the law required a public hiring process; this is sometimes the case with engineering positions at universities and in governments. Fourth, unfortunately, there may be some conscious or unconscious bias the employer has against a job applicant’s age, gender, race, etc., which they would never publicly state, but that still affects their choice of who they hire.

Regardless of the reasons you might get rejected, communicate politely with the employer, thank them for their time and effort, and wish them well with the person they decided to hire. But, don’t probe them too much about why they didn’t hire you. They don’t legally have to state their reasons. You’re probably not going to get a full answer from them anyway other than some vague response that they decided to go with a more suitable applicant. And you might appear to be pushy and, thus, leave a bad last impression about yourself. It’s always best to leave a good last impression with the employer because you never know when you might cross paths again in the future.

If for some reason, you just can’t seem to get any job offers after a long period of time and your financial situation is starting to look very stark, then maybe it’s time to rethink your approach. Maybe it’s time to rethink your idea of a dream job. Maybe it’s time to get some expert help in rewriting your cover letter and resumé. Maybe you’re looking in the wrong places, or not in enough places, for a job. Maybe you need to utilize your social network in a new way to be more effective in helping you find a job. Maybe you need to overhaul your interview skills. Maybe find a part-time volunteer position or unpaid internship, which is still something that can be added to strengthen your resumé, while you keep looking for a suitable full-time job. Maybe start a small engineering business with a few other friends who might be in the same situation, or perhaps become a freelance engineering consultant.

For example, I clearly remember being rejected for a particular engineering job. I sent in my well-prepared application by email, did a telephone interview, and was then invited to do a formal in-person interview with the hiring team. I realized I must have done well so far because I knew that hundreds of people usually apply for that type of engineering job. Then, I prepared well for the interview by anticipating the kinds of questions they might ask, writing down my answers on a sheet of paper, practicing my verbal answers many times, and preparing a short audiovisual presentation at the employer’s request. On the day of the interview, I met and had meaningful one-on-one conversations with several key people, my presentation was well-received as confirmed by several people’s comments to me afterward, and my interview with the hiring committee went smoothly as far as I could tell. The hiring committee even told me that my resumé was very impressive. I honestly thought I would get that job. To my surprise, a few weeks later I received a polite, but clear, email telling me that I was not going to be hired. I didn’t take the rejection personally. So, I responded by email, thanking them for their time and effort, telling them I was disappointed but I understood this was part of the process, and wishing them luck in the future. Why was I rejected? I will never really know, nor do I personally need or want to know. But, a few months later when I was browsing the employer’s website, I discovered who they hired. My resumé was much better than that person’s. But, they were several years younger than me, so maybe that was a factor. Maybe they performed better than me in the interview. And maybe there was a skill they had that I didn’t. My point is that we never know why employers make certain decisions, not to take it personally, and just move on.

Getting Offered an Engineering Job

If you get a job offer, or even multiple job offers at about the same time, don’t necessarily say yes right away. Rather, consider how well a job offer matches with your dream job, which is something we looked at earlier. It’s not likely that every job offer will match your dream job perfectly point-by-point, but hopefully it will match most of your expectations. There’s always going to be something in a job offer that you might not fully understand or like. So, in many of these cases, it’s reasonable to accept the offer.

But, if you are feeling desperate, don’t get tempted to take a truly bad job offer that comes along that’s almost completely opposite to your dream job. If you do take a bad job offer, how long do you think you will really last in that job before you decide to quit? Now, I’m not saying it’s always a bad idea to take a bad job offer. It may actually be a good idea to take a bad job in order to get some engineering experience that can be added to strengthen your resumé, while you secretly keep looking for a better job.

One tried-and-true method of comparing a job offer to your dream job, or for comparing 2 or more job offers to each other, is to create a checklist of factors or a table of pros/cons that are each assigned a numerical value to indicate their level of importance. Then, add up the numerical values of all the factors or pros/cons that you checked off for each job and compare their totals. Such an exercise can help you be as specific and objective as possible, rather than just randomly making decisions.

In any case, if you accept a job, obviously it’s really easy to be polite and grateful over the telephone, video meeting, email message, or paper letter. That’s not really a concern. But, if you decide to reject a job offer, don’t just remain silent and not respond at all. Send a short, clear, and polite communication telling them about your decision and, if appropriate, the reason for it. This is just common courtesy. Also, the other reason is that you never know if you will cross paths in the future with that person, company, or organization, so make sure to leave a positive last impression on them. At this point, either rethink your idea of a dream job, in case you’ve been too picky. Or, just get back to tweaking your cover letter and resumé for each new particular job opening that fits your original dream job idea, and then proceed once more with the process of applying and interviewing.

I think it would be worth sharing a personal situation I had early in my engineering career in accepting and rejecting job offers. A few years after finishing my PhD in mechanical engineering with a specialization in biomedical applications, I secured a part-time contract job as a university lecturer for a few biomedical courses. There, I met some nice people, it was a good learning experience, it paid my bills, and it was something I added to my resumé to strengthen it; I did this for about a year. Then, my boss at the university offered me a renewed and improved, but still part-time, contract as a lecturer, whereby I would teach additional courses and earn more money. I gladly accepted this renewed job offer, which would start again a few months later when university classes resumed. However, a short time later through some accidental social networking that I described earlier in this letter, I wound up getting a second job offer for a full-time permanent biomedical engineering research job. After carefully considering both options, it was clear that I really needed to take the full-time permanent engineering job; it was in-line with my long-term career goals. So, I arranged to meet face-to-face with my university boss in their office and tell them politely that I had to withdraw from the course lecturer contract because, in the meantime, I found a better full-time permanent job. Of course, I felt bad about the situation and apologized to my boss because it would put extra stress on them to find a replacement for me. Fortunately, my boss was very kind, supportive, and understanding of my reasons for taking the other engineering job.

So, What’s the “Take Home” Message of This Letter?

The core message here was that looking for and finding a good engineering job not only takes time and effort, but also there are tactics that can help you. And it is these tactics that I’ve tried to highlight in a logical and useful way. It’s not enough just to have a good engineering education from a university, previous experience working as an engineer, or even connections on the inside. But, you need to know how to sell yourself and even make yourself stand out in a good way from the crowd of other applicants vying for the same job. I do hope this letter has given you pause to think about how to improve your efforts in finding, not just any old engineering job, but your dream job.

Good luck,

R.Z.