Letter 15 Advance Your Engineering Career: How to Climb Ladders and Cross Bridges

Dear Nick and Natasha,

I’m cheered by your openness and interest in my letters on engineering. Thank you kindly. It motivates me to put extra thought into them. In this one, I’m going to tackle the subject of advancing your career. Personally, however, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with being satisfied with your current job situation and, thus, having no great ambition to change career paths. There’s a good deal of comfort in having a routine, knowing what to expect, and avoiding the stress that even comes with good changes.

I honestly think that being an “underachiever” is wonderful. By that I mean there’s more to life than just our careers. There are other priorities we probably should put our time, effort, and resources into. There’s a saying I once heard that goes something like, “Some people live to work, but other people work to live.” There’s some truth to this. At some point in many people’s careers, they don’t want to feed their ambitions anymore and simply want to coast along in their current job until retirement. If this is you, there’s absolutely no shame in it. And so, there’s probably no need to read this letter.

But, if you’re naturally an ambitious person who’s always looking for the next challenge or opportunity, or if you haven’t reached that point yet in your engineering career whereby you want to coast along, then this letter is for you. In this communique, I’d like to discuss advancing one’s career, thinking through the potential good and bad consequences, and making a practical action plan to achieve one’s goals. Because this generic topic is applicable to many fields of endeavor, I’ll also provide some real-world stories of how this has actually worked for engineers I’ve personally known.

Climbing Ladders and Crossing Bridges

I sometimes find metaphors useful in understanding and communicating ideas. Of course, metaphors are limited and don’t necessarily take into account all the possible exceptions. Even so, let me suggest that there are primarily 2 ways of advancing one’s career.

The first way to advance your career is to climb ladders. Perhaps you’ve heard the phrase “climbing the ladder of success on the way to the top” or something similar. It means that a person will move vertically from a lower rank to a higher rank position within the same or different company or organization. The usual motivation is some combination of more money, prestige, authority, and so on. And, in my view, if someone has the talent, opportunity, and initiative to do so, then I wish them all the success in the world, as long as they make the climb upwards without hurting themselves or others.

The second way to advance your career is to cross bridges. Perhaps you’ve heard the joke that asks, “Why did the chicken cross the road?” The answer is, “To get to the other side.” It means that a person will move horizontally from one rank to another similar rank within the same or different company or organization. This could be considered more of an optimization, rather than an advance. The typical reasons could be a combination of higher salary, more desirable work duties, kinder boss, less stress, family reasons, and so forth. Again, in my opinion, if a person’s priority is simply to shift from one job to another very similar job which may have some minor added benefits, then I genuinely hope they succeed.

To be sure, an engineer can advance, or optimize, their job over the course of their entire career by using both tactics. Sometimes they might shift vertically upward and at other times they might move horizontally across. But, there may even be situations when it’s tactical to seek a temporary job demotion in order to position oneself for an eventual huge vertical move upward. The point is that there is no end to the number of ways of adjusting one’s career, it just takes courage and creativity.

What Are the Pros and Cons?

One way of changing your career situation is not better than another. Everybody is different in personality, priorities, and circumstances. So, the trick is to really know ourselves, as the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates (470–399 BC) once said, and figure out what kind of job change we might be looking for. From my experience, ironically, I don’t think most engineers are really systematic or comprehensive in thinking about making changes to their career. There are usually a few added benefits that attract them to a potential new job, and then they go for it. Unfortunately, sometimes this doesn’t work out as well as they hoped, and they regret making the change. I’d like to suggest a checklist of things to ask ourselves before we try to climb a ladder or cross a bridge. This checklist can be more easily remembered by the acronym that I’ve crafted called PASSENGER.

P is for “position.” This refers to the official rank within the company or organization hierarchy. Will the new job you are considering move you up or down in official position and title, or will you be at about the same rank as before?

A is for “authority.” This refers to the type and scope of decision-making ability a job holds within it. Will the new job give you more, less, or the same amount of authority, power, and responsibility compared to what you had previously?

S is for “salary.” This refers to the compensation package that a job offers, including base salary, benefits, vacation time, and retirement plan. Will the new job offer you more, less, or about the same salary, and is there a fixed salary scale or is salary a negotiable item?

S is for “stress.” This refers to the psychological demands and physical difficulties that go along with a particular job. Will the new job bring you pressures on a daily basis that you can truly handle, as well as the occasional work crises that will likely occur?

E is for “engineering content.” This refers to the amount of scientific and technological content of a job. Will the new job let you use all the engineering education and training you’ve received over the years, or will you be moving more and more into the business or management side of things?

N is for “network.” This refers to the type and number of professional contacts that a job affords. Will the new job allow you to expand your network of professional contacts in a strategic way for your future career plans, will it make you more marketable in your field, or will it shrink those opportunities?

G is for “greater job security.” This refers to the likelihood that a certain job will still exist in the long term based on the goals, financial strength, and societal relevance of a company or organization. Will the new job be a long-term place for your career, or will you need to start looking for work again soon?

E is for “extra accountability.” This refers to the moral, legal, financial, and technological liability or culpability that a person with a job has to face. Will the new job make you personally more or less answerable to others for the failure of tasks and projects?

R is for “reputation.” This refers to the prestige or standing that a job has within the company or organization and beyond. Will the new job enhance or diminish how others think of you in your specific workplace, in the engineering field, in your family, among your friends, or within society?

Make an Action Plan for Change

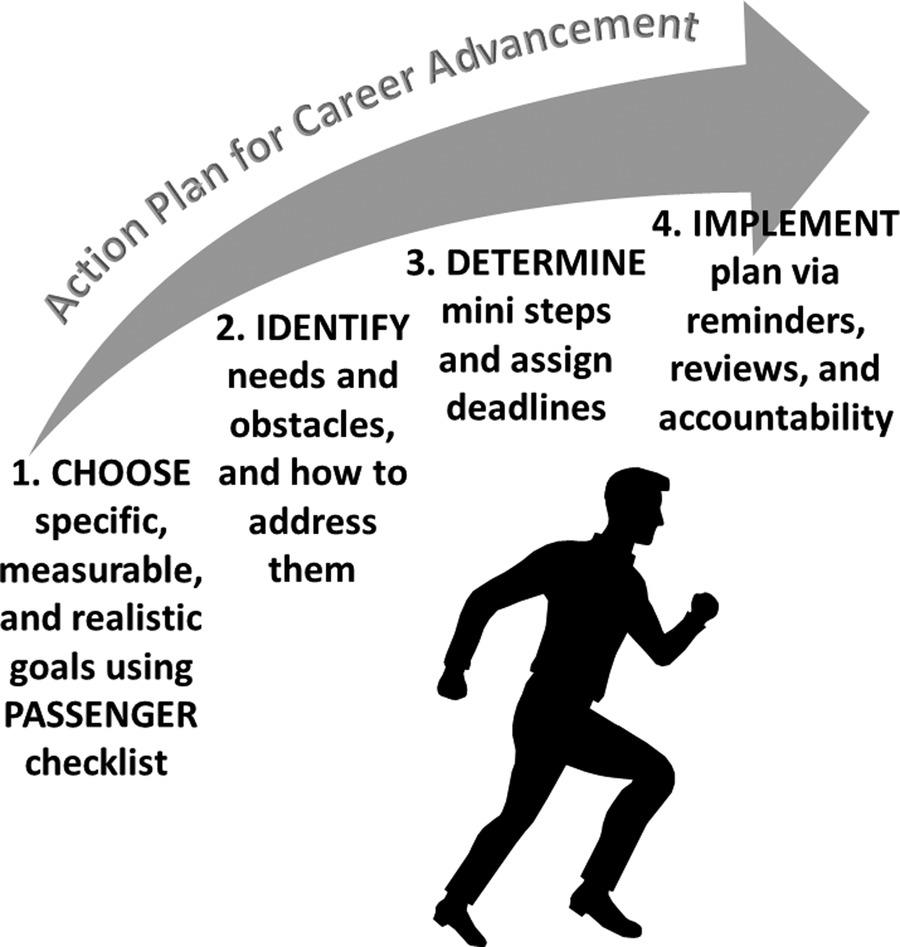

Once you’ve carefully considered the benefits and drawbacks, as mentioned in the earlier section, regarding a potential career shift, then it’s time to make and write down an action plan (see Figure 15.1). Many people think that the vague ideas rolling around in their mind—for example, they want a higher salary or they’d like to have a higher rank in the company—are goals. They’re not! Those are just notions. To turn mere notions into reality requires creating a concrete plan for achieving your goals, as backed by scientific studies and anecdotal evidence. This is absolutely vital. After all, there is some truth to that old proverb that says, “If you fail to plan, then you are planning to fail.” Here are my suggested steps in doing so.

Figure 15.1 Create an action plan to advance your engineering career.

Step 1 is to choose your goal(s). Make sure it’s specific, measurable, and realistic. And write it down. If needed, use the PASSENGER checklist to help you decide. For instance, ask yourself questions like these. Do I want a particular rank, role, or title in the company or organization? Do I want to have direct authority over specific tasks or projects? Do I want to reach a certain annual salary level? Do I want to work from home a certain number of hours each week, so I can bring down my stress? etc.

Step 2 is to identify what you need to reach your goal(s). Be specific here too. Right now, it’s possible you just aren’t qualified to advance your career the way you want. Maybe new “tools” need to be added to your “toolbox.” Otherwise, this will be a perpetual problem. So, do you need to learn a new technical skill, acquire a new university degree, obtain a professional certification, learn from an experienced mentor, talk to a particular individual, make a geographic move, etc? Also, consider if and how you can address other obstacles that might get in your way, like personal bad attitudes or habits, rival applicants for the same job, alterations in employer policies, changes in societal laws, etc.

Step 3 is to determine all the mini steps. Make it super clear. Perhaps draw a road map or flow chart, or write down a checklist or table. Then, input all the individual mini steps that need to be taken that will eventually lead to the desired main goal(s). For each mini step, write down the exact timeframe or deadline, any people or resources you need, and any competition or obstacles that might be faced and how you’ll overcome them. Don’t be hasty. Take your time to think through this process.

Step 4 is to implement the action plan. Now it’s time to put the plan into effect. Remind yourself of the plan by taping it to the wall or putting it on the computer screensaver. Review the plan frequently, say, daily or weekly. Focus on each mini step until they’re each completed. Maybe give yourself a small reward each time you complete a mini step. Make small adjustments to the plan as you go along because you never know what new insights, information, opportunities, or obstacles may arise. Perhaps even ask a friend, family member, or trusted work colleague to keep you accountable in sticking to the plan.

Some True Stories of Engineering Careers

The following series of vignettes are from the careers of engineers I’ve known. You’ll notice that some “climbed ladders,” others “crossed bridges,” and many did both in their efforts to advance their careers. I don’t know what their personal motives were for each job change, how systematically they planned each advance or adjustment in their career, or how happy they ultimately were with each new adventure. But, that’s not the point of these tales. I simply want to highlight the fact that each engineering career was unique and that it had its own twists and turns.

Engineer #1 completed a bachelor of engineering (BE) and an master of engineering (ME) degree. Then, the individual moved to another nation to enroll at university in another ME program, but because of their excellent grades after 1 year, they upgraded directly into a doctor of philosophy (PhD) engineering program. Next, they moved to another city and university for 1 year to do extra engineering training as a post-doctoral fellow (PDF), which was followed by yet another move to a different city and university for 1 more year as a PDF. Subsequently, they moved again to another city and university to take on a new role as a junior professor of engineering, but after 1 year for family reasons, they moved again to another country and university where they also got a job as a junior professor of engineering.

Engineer #2 graduated with a BE degree and then worked as a high school teacher for a year. Then, for a year this person was employed in industry as a quality control engineer. Next, they moved to another country and company for several years because they found work as a production engineer. After this, they moved yet again to another nation to obtain ME and PhD degrees in engineering, as well as extra training as a PDF at the same institution. Then, they moved to another university where they found employment as a junior professor of engineering. But, over the next few years, they were promoted several times to finally become a full tenured professor of engineering.

Engineer #3 finished their BE and ME at one institution but then moved to another university to do a PhD and work as a PDF for 2 years. This person moved again because they accepted a part-time role with a nonprofit charitable organization, but still did freelance engineering work on the side to supplement their income. Next, they taught some university courses for a year. But, then this individual found a full-time permanent position as a senior research engineer in industry, while becoming formally affiliated with a university so they could formally supervise the research projects of engineering students.

Engineer #4 did a BE at one university, then graduated with an ME from another university in the same nation. This person then obtained a full-time job at that same university working in administration as a patent officer dealing with science and technology. During their time of employment, they were also able to complete a master’s degree in business administration and a master’s degree in intellectual property law. This upgrade of their skill and knowledge helped them greatly with their duties as a patent officer.

Engineer #5 completed a BE in their home country, but then moved to another nation to study for their ME degree. Immediately after graduation, this person secured a role as an engineer in industry in charge of fabricating products for a company. After a few years, the company supported the engineer’s desire to move back to their home country for family reasons. While employed with the same company, that individual set up an office and small testing lab in their home and communicated regularly with the head office.

Engineer #6 obtained a BE, worked in industry for a few years, and then did an ME. They moved to another nation to enroll in a PhD engineering program. Upon graduation, this person found a job as a senior technical officer and sales engineer working for their former PhD supervisor who had started a small spin-off company. A few years later, that small company was purchased by a major corporation. So the engineer was promoted to work in the head office of that corporation, which was located in another country.

Engineer #7 received their BE while working at contract jobs as a junior engineer when university classes were not in session. Then, after being a research engineer for a university professor, this person completed an ME. A big change then took place when they left engineering altogether for several decades to work for a nonprofit charitable organization. However, they eventually returned to engineering in a sales and consulting capacity for almost a decade before finally retiring from the workforce.

Engineer #8 completed a BE in their home country, then moved to another nation to finish an ME and PhD degree. Then, for a number of years this person worked in industry before returning to the university to become a professor of engineering. This individual gradually advanced their engineering career by becoming the chair of their department, then the dean of engineering, and then the vice president in charge of a major division of the university. Finally, they became the president of another university for a number of years before retiring from the workforce.

So, What’s the “Take Home” Message of This Letter?

The primary idea I want to convey is that we should think carefully about the pros and cons of changing engineering jobs, either vertically or horizontally. If we’re happy where we are, then maybe there’s no need for change. After all, it’s okay not to have grand ambitions and just bloom where we’re planted. But, if we decide that a career change is something we really want and need, then I hope that my suggestions are instructional and my examples are inspirational.

Best regards,

R.Z.