Letter 16 Personal Organization Skills for Engineers: The “Clompass” Strategy

Dear Natasha and Nick,

How are you doing these days? I hope your response is positive. There’s an old saying that states, “There’s no time like the present.” And so, it’s time for another letter from me. Speaking of which, the topic of this missive is closely related to time. It’s about managing your time and your priorities as an engineer. I guess it’s really about managing yourself. I like to refer to this as personal organization skills.

Unfortunately, most engineers have only informally and haphazardly picked up their personal organization skills, but have never learned about it systematically via a course, book, video, and seminar, or even been mentored by an expert in this area. Yet, this is crucial for an effective and successful engineering career, since an engineer routinely deals with all sorts of people, tasks, projects, and timelines. If you make yourself more efficient, you will be more effective and valuable to your team, employer, client, and customer. And so, this is what motivates me to write about this topic.

I’ll try to balance the rather generic nature of the strategies and tips I’ll describe, by also relaying to you the true story of my own journey of how personal organization skills can improve an engineer’s efficiency and effectiveness. I can honestly say that I wish an engineer with some know-how had shown me, or taught me, about how to manage my time and priorities when I went to school for engineering or during my engineering career.

But, like most engineers, I had to learn this on my own through trial-and-error, reading books, and often accidentally noticing what others did or didn’t do. Although I’m certainly not an expert in this area—since I’m still learning—I’d like to distill everything I’ve learned about the topic in this letter. So, I hope this letter is useful and motivational to you.

Overall Strategy: The “Clompass”

The traditional “to do” checklist some people use to manage tasks is flawed because it doesn’t require prioritization and it doesn’t assign a timeline. In the workplace, this may be good enough for just a few days from time to time. Or if you generally don’t have many responsibilities to deal with in your job. Or if you’re always told exactly what to do, how to do it, and when to do it in your job. But, for an engineer who wants a satisfying and successful career, there’s a better way.

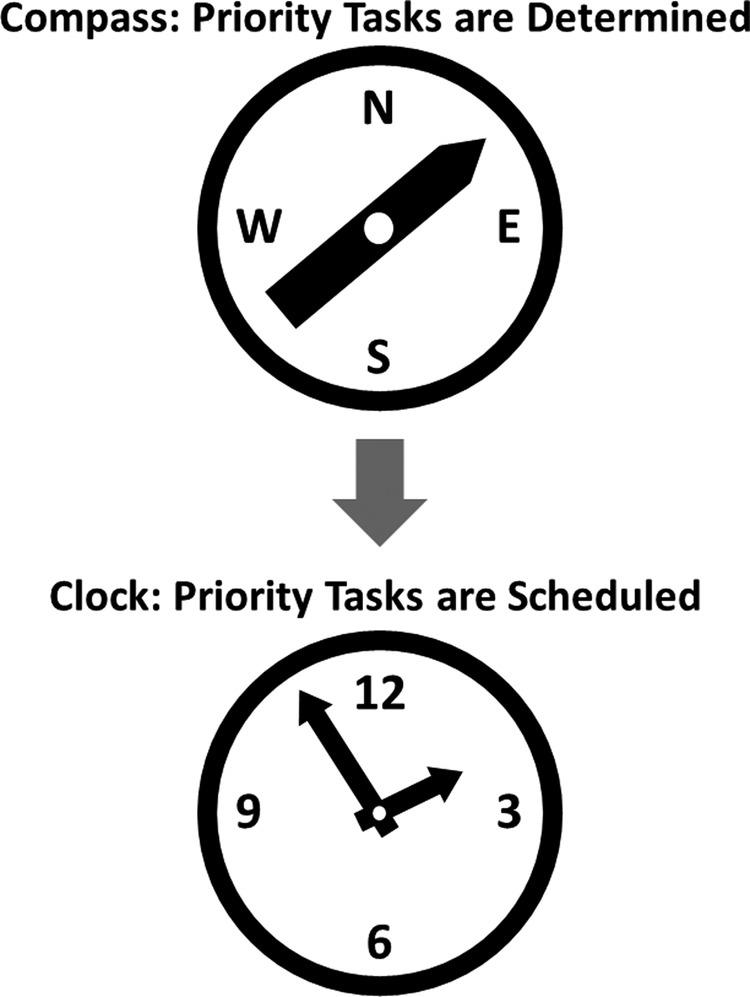

I’m proposing what I call the “clompass” strategy (see Figure 16.1). This is a combination of the words “clock” and “compass.” The compass part of this approach deals with assigning priority levels to tasks based on your short-term job duties (e.g., repair this machine, purchase a device from a supplier, calculate the stress on this component, etc.) and also your long-term career goals (e.g., what projects do you need to finish to position yourself for a promotion? what skills do you need to learn to get an increase in salary? etc.). Then, the clock part of this approach deals with assigning time blocks in your daily calendar to work only on the most important tasks, and then assigning final deadlines for those tasks.

Figure 16.1 The “clompass” strategy for personal organization.

Here’s how this can work practically. Initially, you would organize your tasks into 4 categories, such as 1 (important and urgent), 2 (important and not urgent), 3 (unimportant and urgent), and 4 (unimportant and not urgent). Then, schedule specific time blocks in your daily calendar to only work on important tasks 1 and 2 until they are totally completed. Finally, for unimportant tasks 3 and 4, you either don’t ever do them, work on them only if and when you finish important tasks 1 and 2, delegate them to someone else in your workplace, or outsource them to external departments or businesses.

General Tips

The overall “clompass” strategy is primarily about managing your priorities within certain time frames. But, there are many helpful hints that you can incorporate, or should at least be aware of, as you work the “clompass” approach more effectively. Of course, you have to tailor things your own way to optimize performance. But, here’s my list of 14 extra tips to consider, provided alphabetically, not in order of importance.

Buy a calendar. Purchase a physical paper calendar that has hourly or daily time slots that you can use to schedule your priority tasks. Or, if you prefer, use the hourly and daily calendar functions that automatically come with your smartphone, smartwatch, tablet, or laptop computer.

Delegate and outsource minor tasks. Once you’ve determined which of your many tasks are truly important, your time and energy should really be spent on them. But, even unimportant tasks may need to be done eventually by someone. If possible, delegate these to someone else in the workplace, outsource them to other departments in your company if they have more expertise, or even outsource them to other businesses who specialize in those particular tasks.

Draw a flowchart. It can be very helpful to visually see the task-by-task workflow of a project from start to finish. This can also be useful to help you create a milestone-by-milestone plan for your long-term career goals. Since many engineers are very visually oriented, this can actually be more effective than simply writing down the same thing in words. After all, as the old adage says, “A picture is worth a thousand words.”

Get an accountability partner. Find a trusted family member, friend, or work colleague who will keep you accountable in your efforts at personal organization by regularly asking you if you’ve scheduled this week’s tasks into your calendar, or if you’ve taken a few hours this month to review your long-term career goals. Maybe they can do this by telephone, by email, or over a weekly coffee break. And you can also do the same thing for them to keep them accountable.

Have a planning time. Block off, say, an hour each week to review your prior week’s progress on your various tasks. You can also use this time to prioritize and schedule all short-term tasks into your calendar for the upcoming week. Moreover, you can also block off a few hours each month or every several months to review and plan your long-term career goals. Otherwise, your career will be pulled in all directions.

Just say “no.” It really is a simple, but effective, word. Peer pressure, fun trivial hobbies, unproductive personal habits, and even workaholism can pull us to say “yes,” when we know we should really say “no” in order to focus on achieving our real career goals. But, the more we are able to discipline ourselves and remind ourselves of what we truly want, it becomes easier to just say “no.”

Know your energy cycles. As the saying goes, some people are early birds (i.e., they like to get up early in the morning to start work), whereas other people are night hawks (i.e., they like to stay up late at night to focus on work). But, other people function most efficiently in the middle of the day. Your most energetic time each day depends on numerous physiological and lifestyle factors, so figure out what works best for you and see if you can schedule some of your most important tasks during those high-energy times.

Learn from the experts. Read a book, watch a video, listen to an audio, or attend an in-person or online seminar on time and priority management created by experts in this area who do this full-time for a living. And, you may be able to find an expert who can mentor you as part of a small group or one-to-one for a period of time. This can definitely save you time, stress, and resources.

Organize your workspace. Take a look at your desk, office, workshop, or lab. Is it organized in the most efficient and effective way? Does it invite or discourage unnecessary interruptions by others? Does it allow you to physically access files, books, phones, and other resources easily and quickly? Does it help you focus on what needs to be done, or are there too many distractions like noises, smells, and entertainments? Does it help, or hinder, you to have a small fridge to quickly have some food and drink? Does it help, or hinder, you to have a small couch to take a quick nap from time to time? etc.

Overestimate the time-on-task. Often things take a lot longer than we originally thought. Maybe we thought we could finish a task in 1 hour, but it took 2 hours. Maybe the meeting was only supposed to last 45 minutes, although it ran for 75 minutes. Maybe we purchased something from a supplier who promised to deliver the item to us in 1 week, but it took 3 weeks. So, when we’re scheduling daily tasks into our calendar and estimating timelines for completing projects, we should allow for a margin of error.

Schedule your breaks. Sometimes, we can get so extremely busy with work, that we may not even have time to take a break to eat, rest, socialize, or do nothing at all. If this is a perpetual problem, then it might be helpful to start scheduling break times into your daily and weekly calendar. But, if you do this, the break time needs to be treated as equally important as the work time. It gives you a chance to mentally and physically recharge, so you can be more efficient when you get back to work.

Stack your time blocks. In your daily calendar, one trick for your meetings with people is to schedule them into time blocks that occur one right after the other. That will often help ensure that meetings don’t run overtime. Telling people you have to go to another meeting is also a legitimate excuse not to engage in pointless small-talk with people who like to linger after meetings.

Use the 80/20 rule. Have you heard about the 80/20 rule, also called Pareto’s Principle? Based on good evidence, it states that about 80% of your successful results come from about 20% of the things you spend your time, effort, money, and resources on. Don’t get stuck on the numbers. The reality could be anything like, say, 70/30, 84/16, or 92/8. The point is that you can prioritize your tasks by asking which ones will get you closest to your goal in the shortest time and with the smallest effort.

Write a vision statement. Crafting a vision statement for a project can help clarify and prioritize the daily tasks you have to accomplish for your short-term job duties. Just as importantly, a vision statement can help you determine long-term career goals, which might be different than what you originally thought. Tape these vision statements on the wall, save them to your computer screensaver, and so on. As the old proverb says, “Vision without action is a dream, but action without vision is a nightmare.”

My Journey Toward Personal Organization

Looking back on my engineering education and career, I really wish that someone had shown me some techniques for managing my time and priorities. But, like many folks, I just learned things as I went along, either when I really needed to, or sometimes by sheer accident. In any case, I’d like to share briefly the story of how I learned various lessons about personal organization skills and how they helped me in my engineering education and career.

In high school, I had a daily routine. After classes were done for the day, I’d come home, watch some television, eat dinner, and then go to my room to do homework for 3 or 4 hours. No one told me to do this, not even my parents. But, I guess it seemed obvious to me that, if I wanted to do well in school, this is what I needed to do. And, as a result, I did very well. At the end of high school, I graduated with the second-highest grades in my class and even won a few awards. In general, I didn’t have too many other activities in life or school, so I didn’t feel the need to learn about time and priority management.

But, there was one lesson I did learn in high school from another student about personal organization that helped me perform better. As far as I recall, that student was visiting my country on a student exchange program. He did particularly well in mathematics tests and exams, like algebra, calculus, and relations and functions. I asked him how he was able to achieve his excellent results. He told me he would create a study schedule about a week before an upcoming mathematics test or exam, after which each day he would practice solving a certain number of mathematics problems. It was a simple and common-sense idea. And that’s what I started to do. I was less stressed, better prepared, and my grades improved.

Ironically, when I started to study for my bachelor of engineering (BE) degree at university, some strange “switch” suddenly turned off in my head. I began to socialize a lot more—but nothing negative or self-destructive—and I got involved with a student organization, so I focused on those activities. As a result, I started to procrastinate on completing assignments and preparing for tests, so I often wouldn’t begin studying until very late at night, just before I needed to go to sleep. I didn’t even wear a watch, I didn’t pay close attention to course schedules, and so I was often late attending course lectures. And, at the end of the second year of my BE studies, my course grades were quite poor.

In the third year of my BE studies, I met with a friend of mine who ran the student organization I was involved with. He asked how my studies were going and how my course grades were. I told him I wasn’t doing so well. He then asked if I thought I could do better, and I told him “yes.” He then shared a compelling story with me about a friend of his who completed a master’s of engineering (ME) degree and how that opened up all sorts of life and career opportunities for him. My friend encouraged me not to let my time at university go to waste and to think about my life and career with a long-term view. Suddenly, in that short 1-hour conversation, another “switch” turned on in my head. I realized I wanted to succeed! And so, for the remaining 2 years of my BE degree, I worked hard, prioritized my studies over some other social activities, and achieved excellent grades. I graduated successfully with my BE degree and even obtained a summer research scholarship from the government to work in one of my professor’s research labs.

Next, I successfully applied and enrolled for an ME program at the same university. This required me to complete 4 courses and a major research thesis project. However, I was finding things a bit stressful because of the advanced nature of the courses and the experimental nature of my thesis project. One day, when I was meeting with another engineering student in the cafeteria, I noticed he had an interesting-looking book with him. It was a daily calendar or organizer into which he wrote down all his activities into time slots, like his course lectures, assignment deadlines, social activities, and so on. I don’t think I had ever seen such a book before that moment. I was so intrigued by this daily calendar that I went to the university bookstore, purchase one for myself, and started to organize my time and tasks. This really helped me feel less stressed since I now had better control of my ME studies and the rest of my life.

Also during my ME studies, I read a book on time management. The message I got from the book—rightly or wrongly—was that I needed to be self-disciplined. I thought I needed to wake up 1 or 2 hours before everyone else to get a head start on my activities before other things distracted me. And, if I really tried, I could complete all my personal and professional activities, if I just scheduled them properly. So, I tried this for a while in combination with my new daily calendar technique. This didn’t work for me too well because I realized I still had too many things I wanted to accomplish each day. I still felt a lot of stress and found myself running around doing all sorts of activities from morning until night. Part of my problem at that time was that I hadn’t learned anything about prioritizing my activities and just saying “no.” I thought I could do it all. But, alas, I couldn’t. As the old saying goes, “There just aren’t enough hours in the day.”

I then moved to another university to start my doctor of philosophy (PhD) degree in engineering. This required me to complete 5 courses and a major research thesis project. After that, I started a 2-year post-doctoral fellowship (PDF) in engineering at the same institution. In the midst of these scholarly pursuits, I had a nice social life and was also involved in giving some leadership to a student organization with its various on-campus activities. I seemed to be managing things well. Then, one of the other leaders of the student organization from another campus recommended a book on personal organization skills. This was very pivotal for me. This book talked about priority management, rather than time management. The core of the book’s message was that we each need to decide what our main goal in life is and, then, prioritize all our tasks around that goal. It gave me permission to just say “no” to all the trivial and minor tasks that often distracted me. So, I spent focused time trying to figure out what my main goal was, I wrote it down in a vision statement, and I proceeded to prioritize my activities to be in-line with that goal and eliminate, as much as possible, anything else. I also spent time at the start of each school semester planning and prioritizing my activities. Mind you, I didn’t do this perfectly, but it was a turning point in my approach. This gave me clarity of thinking on personal organization skills that I didn’t have before.

A few years after finishing my PhD and PDF, I moved to another city and eventually got a full-time permanent job as a junior engineer in charge of a hospital-based biomedical engineering research lab that was affiliated with a local university. It was during this time that I read a number of books on leadership skills, biographies of famous leaders, and the 80/20 principle. These gave me insights into how to further develop my ability to manage myself, but also how to manage others effectively, as more and more engineering and medical students became involved with my research lab. Also, I continued to practice just saying “no” when I diplomatically, but clearly, asked my boss if I could just focus my research activities on biomedical engineering, rather than the clinical patient studies he was starting to involve me with. After all, engineering was what I was really qualified for and, thus, I felt I could do a better job doing that, rather than getting into an area that was really not my interest or expertise. Fortunately, my boss agreed. That allowed me to really focus my daily activities and boosted my overall productivity in completing projects and getting the results published as articles in peer-reviewed academic journals.

After several years, I settled in long-term as a senior engineer and research professor. I continued to learn about personal organization skills through experience and various resources. I tried to implement them rigorously. So, I became highly focused and selective about which book writing or editing invitations I accepted, which scientific reviewer tasks I completed for journals, which scientific conferences I attended, and which ME or PhD students I supervised, rather than saying “yes” to everything. I drew flowcharts and used checklists to help me visualize the various personnel and projects I managed, rather than letting ideas just roll around aimlessly in my head. I updated my resumé every time I published a journal article or conference paper or when I graduated a new student, rather than procrastinating for months, only to be stressed out when I needed to dig up that information to provide my department with a progress report. I even eliminated some personal hobbies and habits—sometimes permanently, sometimes temporarily—so I could have more time and energy to focus on my primary career goals. As a result, I had much more satisfaction and success in my engineering career and in my personal life.

So, What’s the “Take Home” Message of This Letter?

The essence of what I’ve written here is that deliberately organizing your priorities and time will make you more efficient and effective as an engineer. It can even make your career and life more enjoyable. Of course, I’m not an expert on this topic. I don’t pretend to be. But, I have definitely invested enough time, effort, and resources to improve my personal organization skills to see real results in my own career. And, I’d encourage you to do the same. You don’t need to learn these lessons the hard way like I did by trial-and-error. Rather, please allow me to suggest that you read just one book or watch just one video on the subject. Then maybe attend a seminar and perhaps eventually find an expert mentor who can coach you for a while on this important career skill. There’s no telling what benefits you’ll experience in your engineering career and your life too.

All for now,

R.Z.