Letter 18 Leadership Skills for Engineers: How to Lead Others Effectively

Dear Natasha and Nick,

I’m pleased to keep interacting with you about engineering. I’ve been somewhat busy these days, but you probably have been too. As you know, a core part of engineering is about designing, building, inspecting, repairing, or disposing of a device, structure, software, database, or process. Sometimes these tasks can be done by yourself. But, often you will work as part of a team, and sometimes you actually may lead a team. Add to that the individual interactions you might have with your supervisors and those working under your supervision, and you start to realize there’s a lot more to engineering than merely technical skills. In these situations, an engineer needs to know how to lead others effectively and also how to be led.

Unfortunately, most engineers just “learn as they go” when it comes to this issue, but have never taken a course, read a book, watched a video, gone to a seminar, or been mentored by an expert. And so, I’d like to focus on this topic here. Thus, the purpose of this letter is to define leadership and then highlight 12 leadership skills. Although many of the skills are obvious, the trick is to put them into practice. To be sure, many of the skills are applicable to any endeavor, whether it’s art, business, education, family, religion, politics, sports, and so on. So, I’d like to give a real-world example from my own engineering career for each leadership skill, so you can see how these ideas can be applied by an engineer; but, I know I still have so much to learn about being a good leader.

Also, I’m sure you can think of other leadership principles, rearrange my ideas in different ways, and find all sorts of resources from real experts who study and teach leadership development on a full-time basis. Nevertheless, I hope this letter at least inspires you to find out more, so you’ll continue to develop your own leadership skills as an engineer. With that said, let’s turn to our topic.

What Is a Leader?

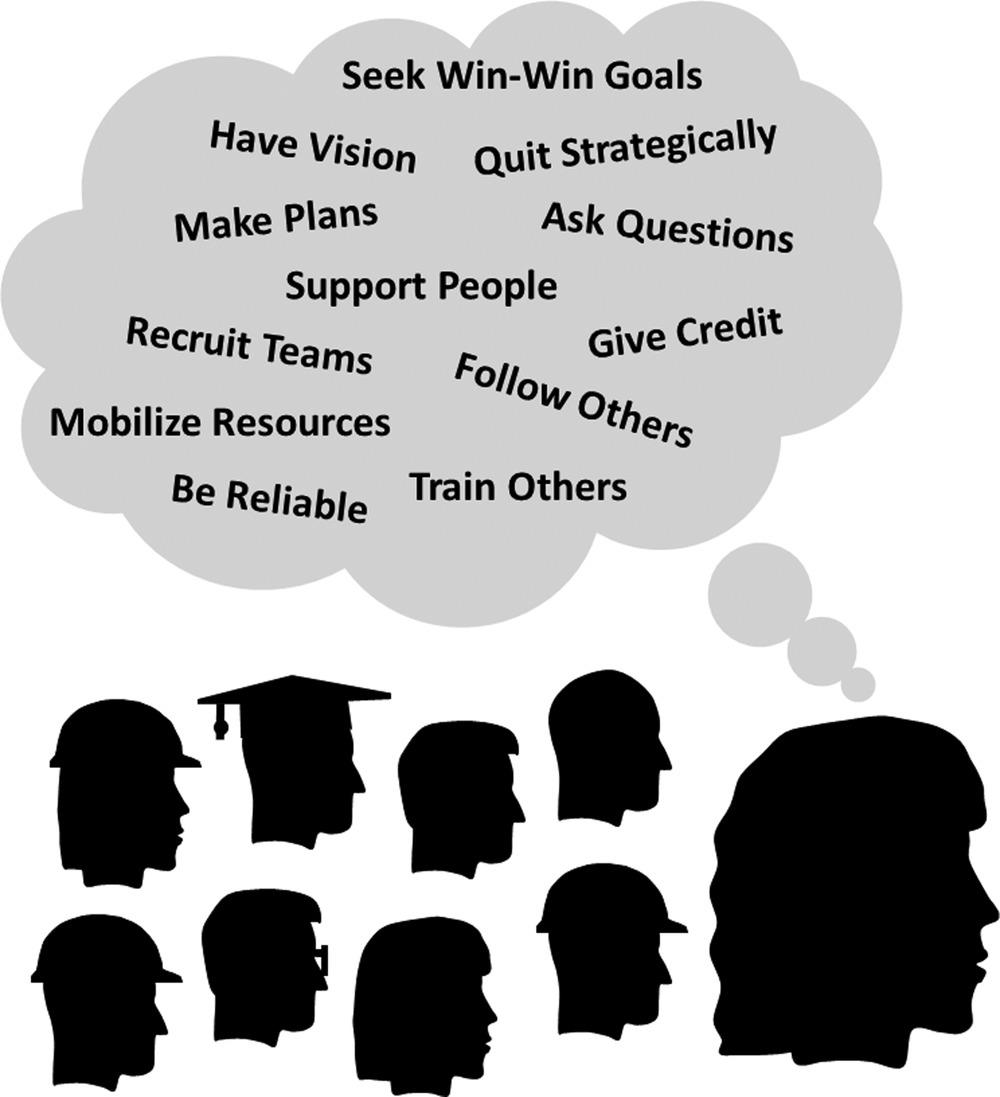

A leader can be defined as someone who has certain skills that help them mobilize people and resources to achieve a particular aim (see Figure 18.1). A leader could be highly experienced or just starting out, aggressive or humble in personality, and the smartest person in the room or of just average intelligence. The people and resources could be vast or few in number. The aim could be grand or modest in scope. But, in all cases, a leader is a person who achieves tangible results or at least tries their best to do so. And, whether they realize it or not, a leader will inevitably influence people around them for better or for worse. As an old saying declares, “More is informally caught, than is formally taught.”

Figure 18.1 Leadership skills for engineers.

Leaders Have Vision

A leader has a picture or image in mind of the ultimate future outcome of anything from a small project to a large endeavor. This will help the leader know exactly what they want to achieve and how to communicate that to others. As the old proverb says, “Vision without action is a dream, but action without vision is a nightmare.” It is very useful to carefully create a concise written vision statement and even practice saying it out loud verbally.

For example, I once had an idea for developing a series of new biomedical implants. To help focus this broad idea for myself, I crafted a written vision statement something like this: “My vision is to establish a biomedical engineering research program dedicated to the design, fabrication, and validation of innovative, patentable, and marketable spine and bone fracture implants made from advanced new materials that solve real-world medical problems.” It’s short, simple, and clear.

Leaders Make Plans

A leader implements a deliberate step-by-step process, whereby the vision for anything from a small project to a large endeavor can be achieved. As the old saying goes, “If you fail to plan, you are planning to fail.” The plan must describe what specific tasks and goals will be completed and what budgets, personnel, supplies, timeframes, etc., will be required. Depending on circumstances, the plan may be developed by the leader alone or with their team, but it can also be used to effectively persuade others to buy into the idea too. Sometimes, the greatest challenge for a leader making plans is to differentiate between a good plan, a better plan, and the best possible plan.

To illustrate the point, let me turn back to the same biomedical implant idea I mentioned earlier. I spent months preparing a long, detailed, written, research plan, as well as giving a series of talks to hospital, university, industry, and government stakeholders. The result was that 3 of the 4 stakeholders bought into my plan and agreed to participate in its realization. The 1 stakeholder that didn’t join up did so due to an internal policy they had, but not because they didn’t agree with the scientific or technological merits of my plan. Although this could have been potentially frustrating for me after all the work I did, I quickly came to realize that this is a common outcome in the world of engineering. Not everybody is going to agree with you. So, the other 3 stakeholders and I joined together to take the next steps to put my plan into action.

Leaders Recruit Teams

A leader finds or invites a group of people to use their own unique experience, knowledge, and skills in order to work together to achieve a common goal. Certainly, an individual leader can make a big difference, but quite often a team is able to accomplish far more. Sometimes a leader will inherit a pre-assigned team, which gives the leader no control over an individual member’s pre-existing strengths and weaknesses. Or, a leader will need to recruit people to the team, which gives the leader a little more control over its final composition. Regardless of the different personalities, knowledge, experience, and skill among the team members, a good leader will try to accomplish a few key things. In particular, an effective leader should work hard to organize the team, function as an integral member of the team, delegate tasks, resolve conflicts, and encourage the team to take ownership of the goal, rather than seeing and treating the team as a mere instrument of the leader’s will. As the old adage says, “There’s no I in TEAM.”

In my case, I know that I personally haven’t had all the experience, knowledge, and skills needed to complete many biomedical engineering research projects on my own. So, I’ve routinely recruited multi-disciplinary teams of mechanical engineers, materials engineers, machinists, technicians, and orthopedic surgeons who have a variety of expertise in computer modeling and analysis, experimental testing, fabrication techniques, and surgical procedures. One of my main tasks in these team contexts has always been to create an environment where everyone truly feels that their contribution is immensely valuable and that everyone has the opportunity to fully make that contribution. Moreover, whenever I have more flexibility in choosing the people I recruit, I look for people whom I consider to be FAST. This stands for “faithful” (i.e., they have a track record of doing what they promise), “available” (i.e., they have the time to fully participate in the project), “skilled” (i.e., they have prior skill or knowledge in the area of need), and “teachable” (i.e., they have an open attitude to learning new things).

Leaders Train People

A leader invests the necessary time, effort, and resources to pass on to others their own skill and knowledge. This benefits the leader by reducing the pressure on them, so they don’t have to micromanage the activities of individuals and teams under their supervision, but it also builds up their own resumé with additional leadership experience to make them more desirable in the workforce. This benefits individual trainees by building up their resumés with more skill and knowledge to make them more marketable in the workforce, but it also benefits individuals and teams to better accomplish stated goals.

And, of course, organizations and companies benefit from quality training of employees because it grows the roster of capable workers within their ranks. At times, there is a fixed formal training process that an organization or company uses that the leader simply implements among the trainees. At other times, the training process can be more flexible, informal, and tailor-made depending on the previous skill and knowledge of the trainees or the specific needs of the organization or company at a given moment. As the old proverb asserts, “Give a person a fish and they will eat a meal, but teach a person how to catch fish and they will eat for a lifetime.”

Now, I have trained many engineers under my supervision on all kinds of testing equipment and fabrication machinery using an acronym that I’ve developed called SHOW. I always start with S which stands for “show”; this means I personally perform the task once or several times while the trainee simply watches what I do. Then, I move on to H which stands for “help”; this means I ask the trainee to perform the task once or several times while I simply help them do it. Next, I move on to O which stands for “observe”; this means I ask the trainee to perform the task on their own once or several times while I simply observe and make helpful comments in case there is a problem. Finally, I move on to W which stands for “walk away”; this means I physically leave the area, room, or building while the trainee continues to independently work on the task until the project is complete, but of course I make myself available to the trainee to deal with any questions or problems that may arise.

Leaders Mobilize Resources

A leader obtains any physical supplies that are required to reach the leader’s aims, such as computers, equipment, materials, physical space, software, stationery supplies, tools, etc., but finances are certainly going to be a factor also. A leader should think through what resources are needed, what quantity of each resource is needed, whether these resources need to be procured permanently or temporarily, how much the resources will cost, how to obtain funding if needed, and so on. But a leader also has to be realistic about what resources they already have and what new ones can actually be obtained; thus, they may need to adjust their vision, even if it will result in more modest accomplishments. As the old saying goes, “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.”

For example, early in my career as a junior engineer, I became the day-to-day manager for a hospital-based biomedical engineering research lab. I soon realized that our research projects could be completed much more effectively without relying as much on outside machine shops for fabrication and outside instrumentation for testing, if we invested additional lab funds to purchase more supplies. So, I approached my supervisor with the idea, got his approval, and proceeded to purchase all sorts of new manufacturing equipment (e.g., band saws, circle saws, drill presses, grinders, etc.), mechanical testing instrumentation (e.g., strain gage system, thermographic camera, etc.), and a large assortment of new hand tools and power tools (e.g., digital caliper, digital screwdriver, etc.).

Leaders Achieve Win-Win Goals

A leader wants every individual or group involved in a project or endeavor to get some tangible return benefit from their investment of time, effort, resources, skills, etc. The type of benefit may have been agreed to before the project began and can vary widely depending on what is ethically and legally appropriate: it could be financial payment, renewal of a work contract, improved reputation in the field, co-authorship on publications, and so on. As the old adage says, “Every bird wants to wet its beak a little in the water.”

At other times, however, perhaps the individual or the group does not even want any return benefit because, as part of their own decision or policy, they have the mandate to make donations or do charitable work as a way to generously give back to others and society at large. In the normal course of events, though, leaders should try to achieve win-win goals for everybody involved.

Let me tell you how a colleague (whose engineering team was university-based) and I (whose engineering and medical team were hospital-based) collaborated a number of times on biomedical engineering research projects. Their team did the computational modeling, while my team did the experimental testing. Their team paid the salaries, while my team purchased the supplies. Their team wrote a first draft of the research article, while my team edited it thoroughly and submitted it to a peer-reviewed journal for publication. And so, it was a fruitful win-win partnership.

Leaders Ask Good Questions

A leader asks insightful questions of others, as well as of themselves. Such questions can cause us to think more deeply and creatively about our aims, plans, tasks, etc., so they can be carried out more effectively. Such questions may even fundamentally challenge the basic underlying assumptions of a system, organization, or institution. At times, a leader’s questions may be welcome because there is a willingness to make the changes necessary to improve things. At other times, a leader’s questions will be resisted because there is a desire to maintain the status quo for personal or ideological reasons. Whatever the case, leaders need to decide when it is appropriate to ask good questions and when it is better to remain silent. As the old proverb says, “Choose your battles wisely.”

As a case in point, my role as a research professor of mechanical/biomedical engineering has been to supervise students in mechanical engineering, materials engineering, orthopedic surgery, and the like. And one of the primary goals of this is to conduct research that is unique and that will make a new contribution to the scientific literature for the betterment of the biomedical engineering field itself, the healthcare system, the medical professionals, the patients, and also society at large. If there is nothing new in what we are doing, why are we doing it? There is no point in reinventing the wheel. Unfortunately, it is easy for anyone to get caught up in the details of the task at hand without asking whether it is worth doing or not. So, one of my habits to refocus my team’s research has been to continually ask my students and myself this simple, but useful, question: What new contribution will this research project make?

Leaders Support People’s Ideas

A leader will encourage other people’s ideas, interests, and goals because it may greatly benefit the leader, team, organization, or company in unforeseen ways. A good leader realizes there may be a lot of untapped creativity and potential in people that should be stirred up, rather than being crushed because the leader is afraid to lose control, inflexible in their methods, or short-sighted in their plans. This takes a lot of psychological maturity and social skills on the part of the leader because people’s egos, emotions, and hopes are involved when they bring new ideas. Leaders who encourage people will earn a lot of respect. As the old saying goes, “People don’t care how much you know, until they know how much you care.”

Obviously, if a person’s ideas are directly opposed to, or could cause great harm to, the leader, team, organization, or company, then it may be best for that person to be released so they can go in their own direction; but, this should be done as amicably as possible. Such a separation can actually be good because it can reduce everybody’s stress and allow them to pursue their own agendas in an unrestricted and productive way.

For example, I have often made sure to ask engineering and medical students if they think there is a way to perform a stress test, compute a value, fabricate a specimen, or perform a surgical procedure that is even better than I originally suggested to them; this simple inquiry sometimes generates a better solution than I originally envisioned. Similarly, I have often told engineering and medical students that I am always happy to write them a good recommendation letter for any new position they apply for, if they decide not to continue with my team after their contract or studies are completed; it’s amazing how such simple acts of respect have helped grow my network of contacts and professional collaborations with a number of these former students and employees.

Leaders Give Credit

A leader should privately and publicly reward and recognize other people’s strengths, contributions, and achievements. This is fair and generous to the other folks, it will motivate them to stay productive, and it will earn the leader respect. All of this can create a positive atmosphere in the team, organization, or company.

In contrast, a leader who hordes all the accolades by claiming or letting others think that they alone accomplished everything will foster resentment and breed enemies. No one wants to put in a lot of time, effort, and resources just so somebody else gets rewarded or recognized. No one wants to be a mere stepping stone on the roadway to someone else’s career success. And so, a leader should understand and respect the fact that other people have their own career aspirations and encourage them in that regard. As the old adage says, “Give credit where credit is due.”

To illustrate the point, I’ve always ensured that everyone on the teams I’ve led received proper credit as co-authors on the biomedical, mechanical, or materials engineering research articles I’ve published in peer-reviewed scholarly journals. Sometimes it is challenging to determine who on the team should have the prized position of being the first author. But, at other times it is very clear which person has done the brunt of the hands-on work and, so, they are acknowledged as the first author; after all, they deserve it.

Leaders Are Reliable

A leader must turn their promises into actions. Others inside and outside the team, organization, or company should see the leader as someone who fulfills their promises to produce tangible results. As the old proverb says, “Say what you mean, and mean what you say.” This kind of reliability gives others a sense of security because they know what to expect from the leader. Of course, leaders are not perfect, so they will sometimes overpromise and underdeliver. But, if they acknowledge their flaws and people see them making improvements, then their reputation for reliability can be restored.

Conversely, if the leader always blames others for failures and is unwilling to make improvements, this can ruin their reputation for reliability. Then, others will think the leader is incompetent or even dishonest. That can create disappointment, frustration, and stress, as well as reducing productivity. Although this kind of negative pressure can still push people to produce results quickly to meet upcoming deadlines, in the long-term it can lower the quality and quantity of the work being done.

Now, an important task in my engineering career has been to complete research projects and make sure our team’s efforts result in articles that are published in peer-reviewed academic journals. Due to my own mistakes in managing time, personnel, or resources, there have been some projects I didn’t complete, but fortunately, this has rarely happened. The vast majority of the time, however, I have earned a reputation for fulfilling my promises and producing concrete results. And so, some of my colleagues have given me nicknames like “The Finisher” and “The Manuscript Monster.”

Leaders Know How to Follow

A leader needs to have prior experience being supervised or mentored as an individual or as part of a team. And a leader may also currently be under the supervision or mentorship of another leader that has a more senior position. Either way, this will help a leader empathize with the questions and challenges of those they are leading. It will continue to give them formal and informal training in developing their own leadership abilities. And it will keep them accountable to others for their actions.

In contrast, a leader who has never been a follower, who thinks they have nothing to learn from others, and who believes they don’t have to answer to anyone for their actions is on their way to being a petty tyrant who misuses their position for personal ambition. This person has disqualified themselves from true leadership. As the old saying states, “Absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

Personally, I have worked on biomedical, mechanical, or materials engineering projects as an ordinary member of a team, or in a supporting role as a co-supervisor, under the leadership of more junior colleagues. I have tried to encourage their growth and respect them in their leadership, even if I had more years of experience on the project’s topic. And so, I made sure to say things to them like “You’re the boss on this project” or “Whatever decision you make is okay with me” or “That’s just my suggestion, but it’s up to you, if you want to do it.”

Leaders Know When to Quit

A leader knows when it’s time to let go of something and move on to the next thing. There is often a natural growth-and-decay process that people, projects, and organizations go through. There may be an initial rise in enthusiasm, funding, recruitment, or productivity, followed by reaching a steady-state or plateau, and then an eventual decline. In some cases, the process may be quite normal and expected, so there is no need for a leader to control or worry about it. This can occur when an employee’s contract comes to an end, the project reaches completion, the funding goal is met, the machine has reached target efficiency, and so on.

However, in other cases, the process may be negatively affected by internal or external factors, so it becomes destructive to participants and resources. This can happen if a person is consistently not performing their duties or meeting deadlines, the project is way over budget, the machine continues to produce too many flawed products, and so forth. At some point, a leader may need to step in to restart, redirect, or end things. In some ways, these kinds of decisions may be extremely difficult for a leader’s ego or career, since it implies that they have failed in some way. Yet, the decision to end something or change course may, in fact, be the wisest thing a leader can do. Also, there’s no shame even in losing or letting something go. And it’s good for our own personal character development to be humbled once in a while and be reminded of our own flaws and limitations. As the old adage declares, “It’s better to retreat from the battle now and then come back to fight another day.”

As a case in point, I’ve had to quit or experience failure a number of times in my own engineering career. I’ve had to give up on publishing some research articles and books because I did not have the time or energy, although the opportunities were there. I’ve had to stop applying for certain grants to obtain project funding because my proposals were repeatedly rejected by decision-making committees. I’ve had to accept the fact that I wasn’t hired for potential jobs that I was really excited about. And, sadly, I’ve had to dismiss some well-meaning engineers from their jobs or tasks because they were consistently not meeting the performance expectations that were previously agreed to.

So, What’s the “Take Home” Message of This Letter?

The main idea in this letter is that you too can continue to expand your leadership skills as an engineer, as opportunities arise. I don’t think there is such a thing as a perfect leader; that shouldn’t stop you from attempting your best. And I definitely have much to learn and apply in my own leadership development. Although leadership can certainly be greatly enhanced by experience, personality, and intelligence, an equally important factor is simply the willingness to try and to grow. So, let’s get out there, find some good books, seminars, websites, and videos, and then move forward in becoming the best leaders we can possibly be.

Good luck,

R.Z.