Letter 21 Protect Your Intellectual Property: Patents, Copyrights, and More

Dear Nick and Natasha,

I hope this letter is a pleasant surprise to you. I sometimes have to hastily—but, I still hope, thoughtfully—write these letters to you in-between my other duties. And maybe you’d say the same thing about reading my letters. In any case, whether we are engineers working in a university, in industry, or with a government, our work will deal with new ideas and products. These may have originated from our own minds and hands, or those of others. But, they are all extremely valuable. Consequently, a new idea or product is often called intellectual property (IP).

Sadly, we live in a world where IP can be misunderstood, stolen, ignored, lost, and even expire. Due to carelessness, ignorance, or downright malice, there are individuals and groups who can take advantage of you for their own benefit. So, it becomes important for engineers to understand how to legally obtain and protect their IP. Yet, many engineers are unaware of how to prevent themselves from becoming victims of breaches, or even how to prevent themselves from accidentally becoming the villains in the story.

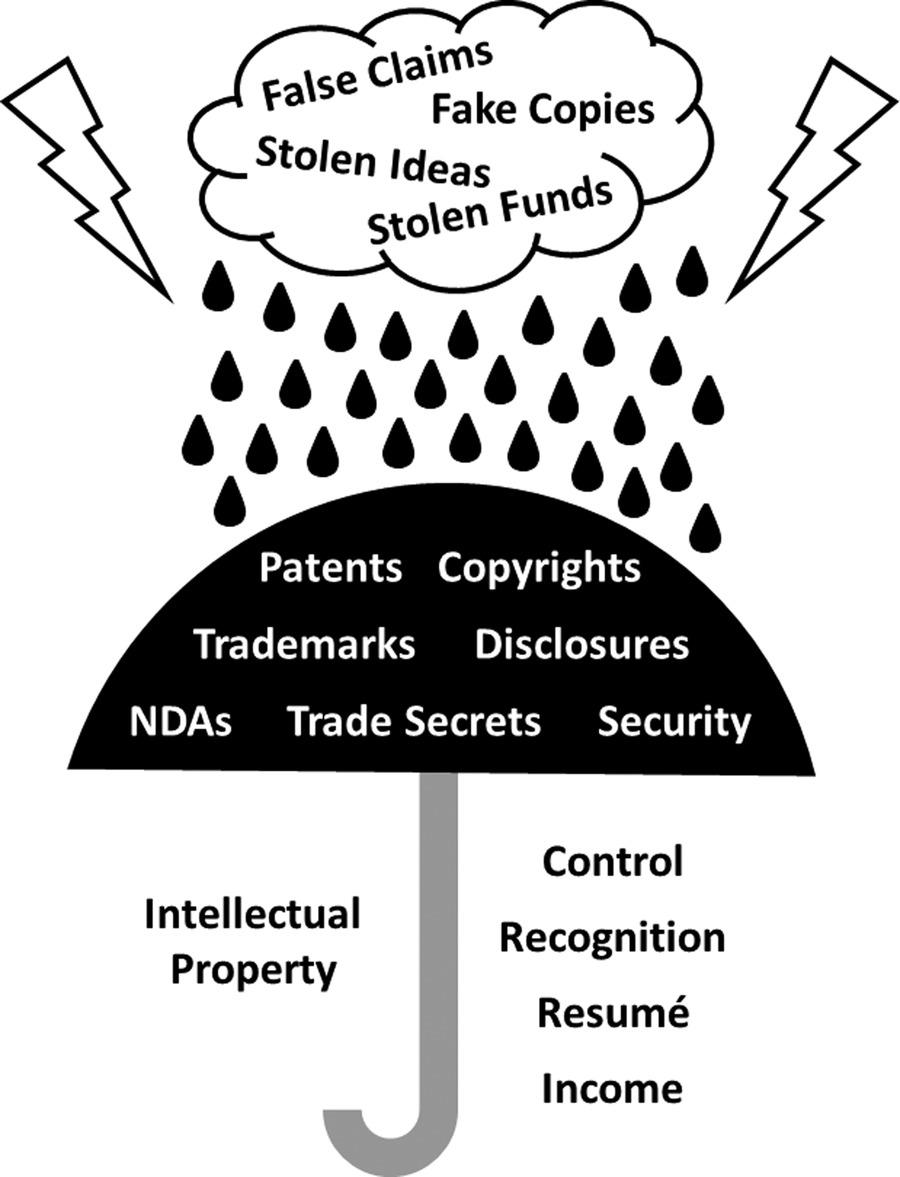

That’s what this letter is about—protecting your IP (see Figure 21.1). Keep in mind that each country has its own particular IP laws, which are often connected with other national IP laws through agreements or treaties; so, it’s important to know the specifics. However, what I’m going to do below is provide general guidelines that do not depend on the IP of any particular nation. First, I’ll discuss the main ways to become the legally recognized inventor and/or owner of your IP. Then, I’d like to describe why you should legally protect your IP. Next, I’ll outline the different ways IP can be misunderstood or violated. And I’ll finish with a few real-world engineering examples. In addition to reading this letter, I’d also encourage you to always seek advice from an educated and certified legal expert on these matters. Now, let’s get to it.

Figure 21.1 Protecting an engineer’s intellectual property.

How Can You Protect Your IP?

There are a few ways that allow you to become the legally recognized inventor and/or owner of your IP. Some of these methods have greater legal strength than others, while others don’t have any legal force but mainly rely on moral obligations between participants. In some instances, you may want to keep your IP totally hidden from all public gaze, as we’ll see.

A patent is a certificate from a national government that gives legal IP protection to an individual or group as the inventor and/or owner of an idea or product, such as a device, software, technique, or process. A patent owner has the legal and exclusive right to make, market, and/or sell the idea or product in that nation, while also preventing others from doing so. A patent owner may or may not temporarily lease their patent to another person or group for a one-time fee or ongoing royalty payment, so that another person or group can make, market, and/or sell the idea or product. A patent is usually granted for an idea or product that is new, useful, and not obvious to others in the field. A patent is generally not granted for discovering laws of nature, phenomena in nature, or mathematical formulas or equations. A patent usually costs money to obtain and maintain, and it may or may not expire by law after a number of years, after which the idea or product is in the public domain; then, anyone can make, market, and/or sell the idea or product. Depending on the nation, a patent could be issued based on the principle of the first to invent vs. the first to register vs. the first to use, so it’s always a good idea to know your country’s patent laws.

A copyright gives legal IP protection for a written or artistic work, such as an article, book, drawing, graph, photo, audio, video, or computer software. A copyright is usually automatically and legally assigned to the creator of that work when it comes into existence and/or when the creator writes the word “copyright” or enters the symbol “©” beside their name on a physical or digital copy of the work. A copyrighted work does not necessarily have to be registered with a national government or international registry, since it’s automatically and legally recognized by many national and international laws. A copyright does not cost money to obtain or maintain. A copyright owner can choose to make, market, and/or sell the work on their own, while also preventing others from doing so. A copyright owner can also sign a contract to give a publisher either temporary or permanent and exclusive or non-exclusive permission to make, market, and/or sell the work, while the work’s original creator obtains no payments (e.g., scholarly journal articles), a one-time payment (e.g., magazine articles and scholarly books), or ongoing royalty payments (e.g., scholarly books). Permission to copy or quote any part of the work, unless stated otherwise in the work, must always be obtained from the copyright owner, who may be either the creator or the publisher at a certain time. A work may potentially be in the public domain in a particular nation so anyone can copy, distribute, and/or sell it if the work’s creator has specifically stated so, if the copyright protection has expired, and/or if the work is considered very old and was created before a certain year.

A trademark gives legal IP protection for a name, word, phrase, or symbol that is used to identify an individual, organization, or company and, hence, its products and services. A trademark needs to be registered with a national government to be legal. Then, no one else has the legal right to use or copy that trademark without expressly given permission from its owner. Also, the owner may or may not ask for a user fee from someone else who has gained permission to use the trademark. A trademarked name, word, phrase, or symbol is usually accompanied by “TM” (i.e., trademark), a circled “Ⓡ” (i.e., registered), or something similar to let others know it is owned by someone. A trademark usually does not expire over time as long as it is being actively used by the owner.

A disclosure is a dated, signed, and witnessed pre-patent confidential statement that an idea or product, such as a device, software, technique, or process, was invented by a person or group. It is usually created if the financial cost of obtaining and maintaining a patent cannot be paid by the inventor due to their momentary personal or financial circumstances. It does not need to be registered or approved by a national government. But, a disclosure may or may not give legal IP protection in a particular nation. Even when a disclosure doesn’t have legal status, it does have some moral authority. This means that professional peers and rivals who are aware of it will feel obligated to respect it, so they don’t get a bad reputation in their field as an idea thief. Disclosures are not just useful before a patent is obtained, but they can potentially also be created before official copyrights and trademarks are secured.

A non-disclosure agreement (NDA) is a dated and signed agreement that the signatories will not privately or publicly reveal any details about an idea or product that is still being developed, such as a device, software, technique, or process. There are no financial costs involved, it does not need to be registered or approved by a national government, and it only expires under the conditions and by the date agreed upon in the NDA. Failure to comply could result in lawsuits, but only if the offended party has the money and means to pursue legal action against the person who broke the agreement. The reason is that an NDA may or may not automatically give legal IP protection in a particular nation. Nevertheless, it does have some moral authority because signatories will feel obligated to respect it, so they don’t get a bad reputation in their field as being dishonest and untrustworthy.

A trade secret is a financially profitable and/or particularly critical idea and product, such as a device, software, technique, or process, whose details have deliberately been kept hidden by the inventors. The inventors don’t want to get legal IP protection through a patent (or a copyright in the case of drawings, photos, or written works) because that would require revealing some technical details. In industry, there is a lot of money at stake, so the inventors don’t want their rivals in the marketplace to make a similar competing idea or product. Also, in the military sphere, governments may not want to reveal certain technical details about weapons, security systems, strategies, policies, etc., so that unfriendly nations don’t get hold of this information. The other benefit is that trade secrets never expire, unlike patents that may expire by law in some countries. Consequently, inventors put in time, effort, money, and resources for cybersecurity and facility security to keep secret the technical details of their idea or product.

Why Should You Legally Protect Your IP?

There are a number of very good reasons why you as an engineer should try to protect your IP through a patent, copyright, or trademark, unless you want or need to keep its details hidden as a trade secret.

Well, firstly, it lets you stay in control. If you are the legally recognized inventor and/or owner of your IP, it’s quite natural to want to determine its fate. You can decide to make, market, and/or sell the new idea, product, work, etc., or not. No one else can tell you what to do with it. You are in charge.

Another benefit is professional recognition. Your reputation as an important and influential person in your field or industry can be boosted when word gets out that you are the official person who thought of and invented a brilliant new idea, product, work, etc. This, in turn, can open up other doors of opportunity for you professionally. And you may be able to leverage this to get a salary raise from your employer.

You can also add this item to your resumé. Your resumé will be greatly enhanced if you are able to state that you are the official IP owner of an idea, product, work, etc. This is a major accomplishment. You should be proud of it. And, if you decide to apply for a new job, this item will greatly impress the potential employer, since it says that you are a high-caliber candidate that stands out from other applicants.

It will give you another stream of income. If you or your company make, market, and/or sell your idea, product, work, etc., permanently to customers or allow customers to use it through user fees, then you can personally obtain some share of the profits. Or, you can temporarily lease your legally recognized IP to another person or group to give them permission to make, market, and/or sell the item, while you get a certain percentage of the profits (i.e., royalties). It’s also possible for you to permanently sell your legally recognized IP to another person or group, which can potentially make you a lot of money.

How Can Your IP Be Violated?

There are several ways you as an engineer can be robbed of the recognition and rewards of being the inventor and/or owner of your IP.

First off, your IP may not really be yours. Let’s say, in a very realistic scenario, that you put in a lot of effort to develop a new idea, product, work, brand name, etc., during your own private time at home without using your employer’s resources. You might think that your new idea, product, work, etc., automatically and legally belongs to you, in other words, that it’s your IP. Not true. It actually may belong to your employer, whether it’s a university, company, or government. After all, they don’t pay your salary just to be nice to you. So, long before you expend a lot of effort generating new concepts, check the details of your employment contract and related documents so you understand how much, if any, of the IP actually belongs to you while you work for your employer. Such policies can vary greatly from one employer to the next.

Also, your IP can be stolen. Let’s suppose you had a casual conversation with a friend or colleague, or you posted something online to your friends on a social media website, about your new idea, product, work, brand name, etc. Or, let’s say your computer, desk, or office were not properly secured. But, this was before you applied for and got legal recognition as the inventor and/or owner of your IP. Then, there is a potential risk that someone can copy your idea, product, work, etc., apply for and get full legal recognition for it themselves, and then they have legal IP status, not you. It may or may not even legally matter if you have documents, photos, videos, or eyewitnesses that say you developed the idea, product, work, etc. What matters is what the law recognizes, so you should be familiar with national and international laws for IP.

Moreover, your IP can be ignored. Let’s say, in this case, that you are legally recognized by the law of one or more nations to be the inventor and/or owner of a new idea, product, work, brand name, etc. And perhaps you are even selling it in the marketplace. Some villainous people will ignore your legally recognized IP. They’ll hack into your computer, have a spy working in your company, or break into your office, and then copy or download all the technical details of your idea, product, work, etc. Then, they’ll manufacture clones of your gadget to sell it, or use your computer code to improve their own software, copy your manuscript, or just sell your technical details to others. Even more easily, they’ll purchase your product legally, reverse engineer it to see how it works, and start making fraudulent clones they can sell. Depending on what country these scoundrels live in, or what legal marketplace or illegal underground network they use to sell their stolen wares, you may or may not be able to do anything about it at all. However, let’s say that you don’t have legal IP in another country and there’s no patent treaty between your country and that other country. Then, those same people are not villains because they may possibly have the legal right to make, market, and sell your invention in that other country.

Additionally, your IP can be lost. Let’s say, in another situation, that a student is asked to help with their professor’s new idea. Or, perhaps an engineer is asked to develop their employer’s new idea. The idea could potentially receive a patent, copyright, or trademark. The student and engineer might think that they have no potential IP ownership because it was not their original idea, although they are going to work on it in some fashion. Then, the professor or employer asks the student or engineer to sign a contract waiving any future IP rights. However, the student and engineer should both get legal advice before they sign such a contract. The reason is that those who conceive an idea like the professor or employer (i.e., conception) and those who bring it into reality like the student or engineer (i.e., execution) may both potentially have IP rights depending on the country. Of course, if the student and engineer are not interested in retaining any future IP rights, then they can go ahead and sign the contract.

Finally, your IP can expire. Let’s consider the same case as discussed earlier, whereby you are legally recognized as the inventor and/or owner of the new idea, product, work, brand name, etc., in a particular nation or nations. The IP belongs to you as far as the law is concerned, but it can expire in one of two ways. In the first instance, you may need to pay fees on an ongoing basis to maintain your legal status as the IP owner, but if you default on these payments you could forfeit your IP ownership temporarily or permanently. In the second instance, your legal status as the IP owner may permanently expire by law after a certain maximum number of years, after which the technical details of your idea, product, work, etc., are then in the public domain. In both instances, this means anybody can now freely use your idea, product, work, etc., for personal or business purposes.

Example 1: Patent Wars

Nikola Tesla (1856–1943) was a famous electro-mechanical engineer biographized by Margaret Cheney and Robert Uth in their book Tesla: Master of Lightning. He had hundreds of inventions and patents to his name, including the brushless alternating current (AC) induction motor, fluorescent lights, the radio, radio remote control, wireless power transmission, the Tesla coil, the “Egg of Columbus,” and so on. He received many awards and honors, for example, the strength of a magnetic field per square area is quantified by the scientific unit called the “Tesla” symbolized by the letter “T.”

In 1887, Tesla applied for and eventually obtained 40 US patents related to his invention of an AC power system for producing and sending large amounts of electricity over long distances. Tesla then sold all 40 patents to the Westinghouse Corporation for a lump sum of cash, stocks in the company, and an ongoing royalty of $2.50 per horsepower for electricity sold to customers. But, by 1897, Tesla released the Westinghouse Corporation from royalty payments to ensure the company didn’t go bankrupt because of its fierce “War of the Currents” rivalry with the direct current (DC) power system promoted by General Electric, the inventor Thomas Edison, and the financier J.P. Morgan. It was Tesla’s AC, not Edison’s DC, system that eventually won the “war” because it was technologically superior for powering cities.

In another situation involving patents, Tesla got embroiled in a controversy about the invention of the radio. In 1893, Tesla publicly demonstrated his system for sending, receiving, and tuning radio signals. In 1896, the inventor Guglielmo Marconi got a British patent for his system for sending and receiving a Morse code signal over 1.25 miles. In 1900, Tesla obtained 2 patents from the US patent office for his radio system. After being repeatedly rejected by the US patent office because Tesla and others had done similar earlier work, Marconi finally got a US patent for the invention of the radio in 1904, in part, due to the influence of big corporations. In 1911, Marconi won the Nobel Prize in physics, which irked Tesla so much that he sued Marconi’s company in 1915 for patent infringement, although Tesla didn’t have enough funds to pursue the lawsuit. Ironically, decades later just a few months after Tesla’s death in 1943, the US Supreme Court re-examined Tesla’s claims and patents and then officially named him as the primary inventor of radio.

Example 2: No Patent, No Reward

Sir Arthur C. Clarke (1917–2008) was one of the grandmasters of science fiction writing, which had earned him many awards and an international audience. His life and works are documented in detail by Neil McAleer in his biography Sir Arthur C. Clarke: Odyssey of a Visionary.

Interestingly, Clarke’s university degree was not in literature, but in physics and mathematics. So, not surprisingly, he was a radar operator in the British air force during World War II. He did some experiments to see if he could bounce radio signals off the moon and receive them again, but it was too far away. However, he realized that if there was a manmade satellite orbiting the Earth that was much closer than the moon, radio signals could be bounced off the manmade satellite and received back on Earth.

These ideas eventually culminated in 1945, when Clarke wrote a seminal non-fiction article titled “Extra-terrestrial relays: can rocket stations give world-wide radio coverage?” in the magazine Wireless World. In it, Clarke suggested that 3 satellites equally spaced in a geosynchronous orbit—that is, rotating with our planet so they are always at the same location above the Earth—would be able to connect the entire world via radio signals.

A number of physicists and engineers read his article and then proceeded to make his concept a reality in 1963 by launching the world’s first geosynchronous communication satellite into orbit at approximately 36,000 km above the Equator. This orbit is named in his honor as the “Clarke Orbit” or “Clarke Belt.” The modern world couldn’t function without this invention, since the modern cell phone, the radio, television, and other signals depend on these satellites.

The only problem, as Clarke later admitted, is that he didn’t bother to patent the idea and, as a result, totally lost ownership and any financial benefit from his own invention. Later, he even wrote a 1960s essay about this incident, somewhat humorously titled “A short history of comsats, or: how I lost a billion dollars in my spare time.”

Example 3: Benefits of Copyright

Researchers in all engineering specialties make their findings known to peers, students, and the broader field by publishing scholarly articles, book chapters, and/or books. So, I’ll summarize my own experience as a published mechanical/biomedical engineer to illustrate what copyright is all about.

First off, my articles are published in peer-reviewed journals to whom I transfer copyright ownership. Then, the journals who own my articles benefit in these ways: (i) exclusive rights to be the first and only ones to publish and distribute my articles in all formats; (ii) their reputation grows as a source of scientific knowledge; (iii) they don’t pay me anything; and (iv) they sell my articles for profit (i.e., traditional journals) or offer them freely online (i.e., “open access” journals).

But, I benefit too: (i) I don’t need to spend any time, energy, or money to publish or distribute my articles; (ii) I can still use the content of my articles at scholarly meetings; (iii) I can still post my articles on my institutional website; (iv) I can still distribute my articles freely for private teaching and research; and (v) I can cite my articles in my resumé to prove to my employer and my peers that I’m a productive scholar.

Now, the book chapters I’ve written that have appeared in other people’s books are produced by science and technology book publishers through the same process I just described above for my articles. As a chapter contributor, I receive authorship credit for my chapter as well as extra benefits like a small honorarium payment, a free copy of the book, and/or a price discount to buy additional copies.

Finally, my books as the sole author—or as the editor who recruits other authors to contribute their chapters—are also produced through the same process by science and technology book publishers. I get the same benefits as my articles and book chapters except that I can’t post free copies online. But, I have the extra advantage of getting ongoing royalty payments from the publisher based on how many books are sold.

So, What’s the “Take Home” Message of This Letter?

If you’re an engineer with an original idea or product, you have created something valuable that can potentially benefit society. And, you deserve to be recognized and rewarded for your effort. So, protecting your IP only makes sense, as does respecting the IP of other engineers. I’ve also tried to offer a general, but useful, discussion on the ways and benefits of doing so. Remember to always seek advice from an educated and certified legal expert on these issues. I know that there is some time and cost involved in securing your IP, but if you are able to do so, it’s worth it in the long run for you and for society.

All for now,

R.Z.