THE COLONEL’S DARK SECRET

Name: Russell Williams

DOB: 7 March 1963

Profession: Colonel in the Canadian armed forces

Previous convictions: None

Number of victims: 2

In May 2005, Russell Williams, a respected member of the Canadian armed forces, commanded flights carrying Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip during the royal couple’s tour of Canada. He performed similar functions for prime ministers Paul Martin and Stephen Harper. Williams’ public persona played on duty, responsibility and trust, all of which would prove to be misplaced.

David Russell Williams was born on 7 March 1963 in Cardiff, Wales, but lived – and will live – nearly his entire life in Canada. Though shaken by his parents’ divorce, and his mother’s subsequent marriage to a family friend, his upbringing was otherwise comfortable. He attended both public and private schools, ending his education in 1986 with a BA in Economics and Political Science from the University of Toronto. The graduate’s next move came as a surprise to even his closest friends. Influenced by the newly released Top Gun, starring Tom Cruise as a cocky fighter pilot, Williams joined the Canadian armed forces. To some, this sudden change in direction seemed surreal; Williams had never before expressed any interest in the military.

Yet, in the face of his friends’ misgivings, Williams took to this new career path. In 1990, he earned his wings, and on New Year’s Day 1991 was promoted to captain. Over a 23-year military career, Williams was given increasingly important responsibilities. He piloted jets carrying VIPs, served as Director General Military Careers and was made commander of the 437 Squadron. Following a six-month tour in the Persian Gulf, where he was in charge of the Theatre Support Element at the secretive Camp Mirage, Williams was posted to the Department of National Defence Headquarters in Ottawa.

The perfect package

Williams rose to the level of colonel, and in July 2009 was appointed commanding officer of Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Trenton in Ontario, Canada’s largest air force base. To his superiors, Williams seemed to be the perfect package. He was considered a good leader, someone who was well organized and adept at administration. Lieutenant General Angus Watt, then the commanding officer of Canada’s air force, described Williams as ‘unusually calm, very logical, very rational’. The colonel was also recognized as a man who was extremely comfortable in speaking to the media.

This last feature was particularly important to the brass. During the war in Afghanistan, CFB Trenton served as the departure point for soldiers going overseas. It was at the base that the men and women serving in Afghanistan would take their final steps on Canadian soil… and it was here that the fallen would return. The responsibility was heavy, but the job was not without its perks. As commander, Williams had living accommodation on the base. This comfortable abode became his third home. He owned a cottage – more of a small house, really – on Cozy Cove Lane in Tweed, a pretty town of 5,000 or so inhabitants, about an hour’s drive northeast of Trenton. Situated on a lakefront property, it offered a lovely view of picturesque Stoco Lake. But Williams didn’t get out on the water often. His neighbour, Larry Jones, remembers the colonel as a busy man, someone who would be coming in and out at all hours. ‘This guy comes in in the dark and leaves in the dark. Never see him. He has a controller for his garage — just slides right in. I figured, “Well, that guy’s a busy man — base commander and all.”’

The colonel’s wife, Mary-Elizabeth Harriman, would usually stay at the third Williams home in Ottawa. Being partway between Trenton and the national capital, the cottage served as a meeting point for a couple that spent much more time apart than together.

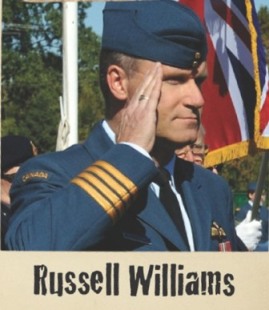

Position of trust: Williams was in control of flying dignitaries across Canada

To at least a few friends, their relationship appeared slightly odd. Williams had had one – and only one – girlfriend while attending university. When that relationship ended, he did not date for nearly a decade. To even his closest friends, Williams’ 1991 marriage appeared to have come out of the blue.

Strange compulsion

Williams’ wife would come to the Cozy Cove cottage on weekends – but not with any great frequency. It seems unlikely that she would have been in Tweed on the autumn 2007 weekend when her husband first planted the seed of fear in the small town. There was little concern at first; a young woman had returned home to find a tall figure in jogging clothes attempting to break into her house. Whoever it was had been scared away. Just a neighbourhood kid was the thought.

No one suspected the colonel. However, it wasn’t long before other break-ins, successful break-ins, were reported. The intruder appeared to have no interest in money, jewellery or electronics; it was women’s intimate apparel, swimsuits and shoes that were being stolen. Williams would break, enter and steal from over 42 different Tweed homes, sometimes hitting two in a single evening. Among the houses he entered were the three immediately to the south of his cottage. There were times that the violations were obvious, but in many cases Williams took pains to leave no sign of his crimes.

Although no one made the link at the time, the Tweed break-ins were not dissimilar to those that had been taking place three hours away around his Ottawa home. In January 2007, he entered a nearby house, stole underwear belonging to a teenage girl and left what was described as ‘DNA evidence’ on the bureau. Before the end of 2009, Williams made at least two dozen similar neighbourhood break-ins.

More than a thousand articles of clothing were stolen. The community grew tense, with many people fearful for their safety and that of their loved ones.

The concern was understandable; the break-ins were increasing in frequency. In the two months that followed Williams’ promotion to commander of CFB Trenton, no fewer than ten Tweed homes were broken into. For those investigating the crimes, it was all so predictable. Lingerie, swimsuits, shoes and robes were stolen, along with the occasional photograph; DNA evidence was sometimes left behind.

However, on 17 September 2009, just hours after his return from a trip to the high Arctic, Williams’ routine underwent a dramatic and disturbing change. Not long after midnight, a young Tweed mother was awoken by a masked intruder. Over a two-hour period, she was sexually assaulted, threatened and photographed. The woman’s 8-week-old baby, asleep nearby, was unharmed during the ordeal.

The following evening, as police were investigating the assault, Williams returned to the home and, incredibly, broke into the very home in which the sexual assaults had occurred. A week later, after having spent the day at CFB Trenton with the Minister of Defence, Peter MacKay, he broke into the house a third time.

With the sexual assault, Williams’ deviant pattern had changed. Before the month was out, the colonel repeatedly broke into a house not far from his cottage. It was not until his third home invasion that he encountered anyone. Like the first – like all of them – Williams’ victim was a woman. She was home alone when he broke in. Threatening her, Williams placed a blindfold over the woman’s eyes, bound her to a chair and then cut off her clothes. Over the next two and a half hours, she was choked, beaten, sexually assaulted and photographed. Throughout the waking nightmare, the victim thought that she recognized the voice of her assailant.

Williams liked to take photographs of himself in his victims’ underwear

By the morning, little Tweed had become a focus of the Ontario Provincial Police. Cozy Cove Lane was blanketed by investigators, but Williams wasn’t at home. It hardly mattered. Once investigating officers learned that he was commander of CFB Trenton, he was considered above suspicion. Instead, they set their sights on Williams’ next-door neighbour, Larry Jones, who owned one of the homes that had not reported a break-in. The second sexual assault victim had guessed that the voice she recognized belonged to Jones. Weeks passed before he was cleared.

As his neighbour came under investigation, the path Williams was heading down became even darker. In mid-November, he broke into the home of a woman who taught music at CFB Trenton. The colonel stole underwear and sex toys, and left an intimidating message on her computer. His victim later realized that she and Williams had been in the house at the same time. In a way, she’d been lucky.

Williams broke into the home of a woman who taught music at CFB Trenton. He stole underwear and sex toys, and left an intimidating message on her computer

Williams’ next victim, Marie France Comeau, also had links to CFB Trenton. A 38-year-old corporal in the armed forces, she lived in the nearby town of Brighton, a 15-minute commute from the base.

On 25 November, three days after she’d finished serving on a flight crew that had attended to Prime Minister Stephen Harper during a state visit to the Far East, Comeau’s body was discovered in her home. She had been strangled.

That same day, Williams, as base commander, sent a letter to the murdered woman’s family. ‘Please let me know if there is anything I can do to help you’, he wrote. However, his support only extended so far; the colonel did not attend the funeral.

It would only be a matter of weeks before Williams would kill again. His victim, 27-year-old Jessica Lloyd, lived alone on Highway 37 in a modest house that her murderer had passed dozens of times in driving between Trenton and Tweed.

Lloyd was last heard from on the evening of 28 January 2010, when she’d texted a friend goodnight. Nothing appeared at all unusual until the following morning when she failed to show up for work. A search of her house raised the level of concern; her identification, keys and cellphone were all accounted for.

The search for the missing woman lasted more than a week. It involved not only the local police, but the Search and Rescue team from CFB Trenton. Then, in the midst of the stubborn mystery, investigators caught a very lucky break. Two men reported that on the evening of the disappearance, they’d noticed an SUV parked in the middle of a field that bordered Lloyd’s property. Though several days had passed, the SUV’s tyre tracks – distinctive tyre tracks – remained preserved in the frozen snow.

A roadblock was set up along the highway. On 4 February, a week to the day after Lloyd was reported missing, Williams found himself amongst the hundreds of drivers on the receiving end of police questions. After a brief exchange, he was sent on his way. What the colonel didn’t know was that in those few minutes he had become the prime suspect. From that point on, Williams was under police surveillance.

The police had, again, caught a lucky break. That day, Williams happened to be behind the wheel of his SUV, rather than his much-preferred BMW. After three days, police phoned Williams at his Orleans home, asking that he come to the Ottawa Police Service headquarters to answer questions. According to some reports, the colonel arrived thinking that the queries would be about Larry Jones, his neighbour.

The end of the game

Instead, the colonel was subjected to an interrogation conducted by Detective Sergeant Jim Smyth of the Ontario Provincial Police’s Behavioural Science Unit. Recordings of the ten hours that followed are now studied by law enforcement officers the world over as an example of how to obtain a confession.

It was, in some ways, a psychological chess game in which a very intelligent man was outmanoeuvred by another. Yet Smyth was careful not to present himself as an opponent. Instead, he calmly presented layers of evidence, which all led to this fifth-hour exchange:

SMYTH: So what am I doing, Russ? I put my best foot forward here for you, bud. I really have. I don’t know what else to do to make you understand the impact of what’s happening here. Can we talk?

WILLIAMS: I want to minimize the impact on my wife.

SMYTH: So do I.

WILLIAMS: So how do we do that?

SMYTH: Well, you start by telling the truth.

WILLIAMS: Okay.

SMYTH: Okay. So where is she [Jessica Lloyd]?

WILLIAMS: Got a map?

Even as he was being interrogated, police acting on search warrants were combing through Williams’ homes in Orleans and Tweed. They discovered the stolen underwear, bathing suits, robes and shoes. He’d grabbed pictures of several women and girls from whom he’d stolen the apparel. But there were more photographs: thousands of images Williams had taken of the two women he’d assaulted, along with the two he’d murdered. There were other photos he’d taken of himself wearing the stolen undergarments. The colonel had unwittingly made the investigation even easier with a notebook in which he’d recorded the dates and the addresses of his crimes, with an inventory of the items that he’d stolen.

The day after his interrogation and confession, Williams led police to Jessica Lloyd’s body, which he’d dumped in a wooded area just ten minutes from the Cozy Cove cottage.

Williams was charged with two counts of first-degree murder, two counts of sexual assault, two charges of forcible confinement and 82 further charges relating to theft and breaking and entering. Awaiting his day in court, the colonel tried to commit suicide by stuffing a toilet paper roll down his throat, but was thwarted by prison guards.

On 22 October 2010, this man who had once been entrusted with the safety of Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip received two life sentences for first-degree murder, four ten-year sentences for forcible confinement and sexual assault, and 82 one-year sentences for burglary. The same day, Williams was stripped of his commission, ranks and awards. In what is believed to be an unprecedented action, his uniform and medals were destroyed.

Breakthrough: Distinctive tyre tracks found at murder scene

Behaviour in court: Defeated

Statement of defence: ‘Why? I don’t know the answers. And I’m pretty sure the answers don’t matter.’

Sentence: Two life sentences, four ten-year sentences and 82 one-year sentences