DEATH FARM

Name: Robert Pickton

DOB: 25 October 1949

Profession: Farmer

Alias: The Pig Farmer Killer

Previous charges: Attempted murder (dropped), firearms offences

Number of victims: 6 to 49

When Robert Service first cast his eyes on British Columbia, the poet described what he saw as being ‘something greater than my imagination had ever conceived’. Canada’s westernmost province is known for its natural beauty. Robert Pickton saw these wonders on a daily basis, but his immediate surroundings were much less attractive.

Pickton lived on a pig farm, a muddy, run-down 17-acre parcel of land in Port Coquitlam that he and his siblings had inherited from their parents.

On the occasions that he left his home, Pickton could often be found 30 km (20 miles) away hunting down the drugged and desperate in Vancouver.

For runaways, the homeless and those who were simply down on their luck, British Columbia’s biggest city holds an understandable allure.

Nestled by the warm Pacific Ocean, it enjoys a much milder winter than any other major Canadian city. For the drug addict, there’s a steady supply of illegal narcotics flowing through its port. For those who still dream of sudden fame, there is fantasy to be found in the city’s healthy film industry; ‘Hollywood North’ is just one of Vancouver’s many nicknames.

Sadly, Vancouver is also by far the most expensive city in Canada; in North America it is surpassed only by Manhattan proper. Real estate is at a premium, and rental units are expensive and hard to come by. This city, with the highest concentration of millionaires in North America, is also home to the poorest neighbourhood in the country. Haunted by glorious buildings, reminders of long-gone days as a premier shopping district, Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside is a blight on the utopian landscape. The banks disappeared years ago, as did the well-stocked department stores. The few shops that aren’t boarded up house lowly pawnbrokers. Outside their doors, and in the blocks that surround, prostitutes – some as young as 11 years old – ply their trade.

Port Coquitlam stands near beautiful countryside. PoCo, as it is known, is Canada’s 88th-largest city by population

Monstrous appetites

Pickton did not prey on children. It’s thought that his first victim was a 23-year-old woman named Rebecca Guno, who was last seen on 22 June 1983. She was reported missing three days later – a very short time period compared to the many that followed. The next victim, Sheryl Rail, was not reported missing for three full years. The lives of Guno and Rail were just two of the six Pickton is known to have taken in his first decade of killing. With as much as 28 months separating one murder from the next, the pig farmer had no clear pattern. These early erratic and seemingly spontaneous killings enabled Pickton to pass under the radar. It wasn’t until the closing years of the millennium that speculation began to surface that a serial killer just might be at work on the seedier streets of Vancouver. By then Pickton had picked up the pace; it’s believed that he killed nine women in the latter half of 1997 alone.

The next year, the Vancouver Police Department began reviewing cases of missing women stretching back nearly three decades. By this time, talk of a serial killer was a subject of conversation in even the most genteel parts of the city, and still authorities dismissed speculation.

When one of their own, Inspector Kim Rossmo, raised the issue, he was quickly shot down. ‘We’re in no way saying there is a serial murderer out there,’ said fellow inspector Gary Greer. ‘We’re in no way saying that all these people missing are dead. We’re not saying any of that.’

The police posited that the missing women had simply moved on. After all, prostitutes were known to abruptly change locations and even names. Calgary, 970 km (600 miles) to the east and flush with oil money, was often singled out as a likely destination.

Years later, veteran journalist Stevie Cameron would add this observation: ‘There were never any bodies. Police don’t like to investigate any case where there isn’t a body.’

In 1997, Pickton got into a knife fight with a prostitute on his farm that resulted in both being treated in the same hospital

Even as the authorities dismissed the notion of a serial killer, Pickton continued his bloody work. Among those he butchered was Marcella Creison. Released from prison on 27 December 1998, she never showed at a belated Christmas dinner prepared by her mother and boyfriend. Sadly, 14 days passed before her disappearence was reported.

The waters were muddied by the fact that some of the women who had been reported missing were actually found alive. Patricia Gay Perkins, who had disappeared leaving a 1-year-old son behind, contacted Vancouver Police after reading her name on a list of the missing. One woman was found living in Toronto, while another was discovered to have died of a heroin overdose. However, the list of missing women continued to grow, even as other cases were solved.

Accepting, for a moment, that there was a serial killer on the loose, where were the police to look? There was, it seemed, an embarrassment of suspects – dozens of violent johns who had been rounded up on assault charges during the previous two decades.

However, Robert Pickton was not among them. Should he have been?

In 1997, Pickton got into a knife fight with a prostitute on his farm that resulted in both being treated in the same hospital.

Nurses removed a handcuff from around the woman’s wrist using a key that was on Pickton’s person. He was charged with attempted murder, though this was later dismissed.

In 1998, Bill Hiscox, one of Pickton’s employees, approached police to report on a supposed charity, the Piggy Palace Good Times Society, that was run by Robert and his brother Daniel. Housed in a converted building on the pig farm, Hiscox claimed that it was nothing but a party place populated by a rotating cast of prostitutes.

It wasn’t the first police had heard of the Piggy Palace Good Times Society. Established in 1996 to ‘co-ordinate, manage and operate special events, functions, dances, shows and exhibitions on behalf of service organizations, sports organizations and other worthy groups’, it had continually violated Port Coquitlam city bylaws. There were parties – so many parties – drawing well over 1,000 people to a property that was zoned as agricultural.

The strange goings on at the Piggy Palace Good Times Society might have been a concern, but Hiscox’s real focus had to do with the missing women. The Pickton employee told police that purses and other items that could identify the prostitutes would be found on the pig farm.

Police visited the Port Coquitlam property on at least four occasions, once with Hiscox in tow, but found nothing. Robert Pickton would become nothing more than one of many described as ‘a person of interest’.

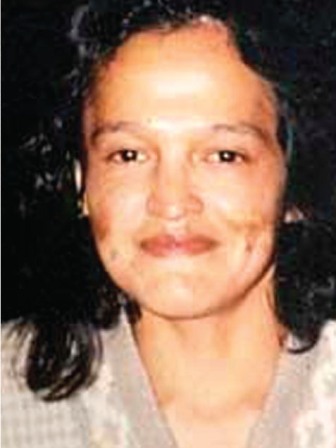

The death of Dawn Crey, 43, was only confirmed when police found her DNA on the farm

Mission to murder

The years passed, women kept disappearing, and still the notion of a serial killer at work in the Downtown Eastside was dismissed.

By 2001, the number of women who had gone missing from the neighbourhood had grown to 65 – a number that police could no longer ignore. That April, a team called ‘The Missing Women Task Force’ was established. The arrest of Gary Ridgway seven months later by American authorities brought fleeting interest. Better known as the ‘Green River Killer’, Ridgway killed scores of prostitutes in the Seattle area, roughly 240 km (150 miles) south of Vancouver. The many murders coincided with the disappearances of the missing women, but it quickly became clear that Ridgway had had nothing to do with events north of the border. The Missing Women Task Force looked into other American serial killers, as well, including foot fetishist Dayton Rogers, ‘The Malolla Forest Killer’, who had murdered several prostitutes in Oregon.

Despite the newly established task force, prostitutes continued to disappear. No one foresaw the events of February 2002.

Early in the month, Pickton was arrested, imprisoned and charged with a variety of firearms offences, including storing a firearm contrary to regulations, possession of a firearm without a licence and possession of a loaded restricted firearm without a licence. In carrying out the search warrant that led to the charges, police uncovered personal possessions belonging to one of the missing women.

Pickton was released on bail, but was kept under surveillance. On 22 February, he was again taken into custody – this time to be charged with two counts of first-degree murder in the deaths of prostitutes Serena Abotsway and Mona Wilson. The pig farmer would never again experience a day of freedom.

The Pickton farm soon came to look like something out of a science fiction film. Investigators and forensics specialists in contamination suits searched for signs of the missing women. Severed heads were found in a freezer, a wood chipper contained further fragments, and still more were found in a pigpen and in pig feed. These were easy finds; a team of 52 anthropologists were brought in to do the rest, sifting through 14 acres of soil in search of bones, teeth and hair. Their diligence brought over 10,000 pieces of evidence – and, for Pickton, a further 24 counts of murder.

But to the citizens of Vancouver, particularly the friends and families of the missing women, the breakthrough had come far too late. In place of praise came criticism. How was it that the police had found nothing at all suspicious when they’d visited the farm just a few years earlier? Serena Abotsway, Mona Wilson and several other women whose body parts were found on the farm had disappeared after those initial searches. Might their lives have been spared?

We might add to these questions: What do we now make of Robert Pickton? A decade after he made headlines as Canada’s most prolific serial killer, his picture is still coming into focus.

Pickton promised prostitutes not only cash, but drugs and alcohol, if they would only come to Piggy Palace. It’s thought that he would almost invariably accuse each of his victims of stealing. He bound each woman, before strangling them with a wire or a belt. Pickton would then drag his victim to the farm’s slaughterhouse, where he would use his skills as a butcher.

Police went through Pickton’s property with a fine-tooth comb – their diligence produced over 10,000 pieces of evidence

Some remains he buried on the farm, while others were fed to his pigs. Still more was disposed of at West Coast Reduction Ltd, an ‘animal rendering and recycling plant’ located well within walking distance of Main and Hastings, the worst corner in the country. In fact, dozens of prostitutes strolled the streets in the shadow of the plant. Eventually, the remains would find their way into cosmetics and animal feed.

Testing found the DNA of some victims in the pork found on the farm. The meat processed on the farm was never sold commercially, though Pickton did distribute it amongst friends and neighbours.

‘Nailed to the cross’

It took nearly five years and $100 million to prepare the case against Pickton. The pig farmer denied his guilt to all but one person: a police officer who had been posing as a cellmate. The pig farmer’s words were caught by a hidden camera: ‘I was gonna do one more, make it an even 50. That’s why I was sloppy. I wanted one more. Make… make the big five O.’

Pickton seemed to acknowledge that he was stuck, that there was no way he would be found not guilty. ‘I think I’m nailed to the cross,’ he told the bogus cellmate. ‘But if that happens there will be about 15 other people are gonna go down.’

The statement only added to suspicions that the remains found on the pig farm weren’t solely Pickton’s work. Yet, on 22 January 2007, when the pig farmer finally had his day in court, he went alone.

The trial proceeded on a group of six counts that had been drawn from the 26 that Pickton faced. As explained by Justice James Williams, the severing had taken place in the belief that a trial dealing with all 26 might take as long as two years to complete, and would place too high a burden on the jury.

As it turned out, Pickton’s trial on the six charges lasted nearly 11 months, and was the longest in Canadian history. Pickton, who had pleaded not guilty on all counts, sat barely paying attention as 128 witnesses took the stand.

That he was found guilty came as a surprise to no one, though the details of the verdict were unexpected. On 9 December 2007, after nine long days of deliberation, jurors found Pickton guilty only of six counts of second-degree murder. The men and women were not convinced that Pickton had acted alone.

Robert Pickton was sentenced to life in prison. Though he will be eligible for parole after 25 years, it is unlikely to be granted.

Danger signs: Assault with a knife on a prostitute

Breakthrough: Evidence discovered while carrying out a search for illegal firearms

Behaviour in court: Bored, distracted, given to doodling

Judge’s pronouncement: ‘Mr Pickton’s conduct was murderous and repeatedly so. I cannot know the details but I know this: what happened to them [the women] was senseless and despicable’

Sentence: Life without parole